Legal Pluralism in Dispute Resolution on Election Justice

Herdi Munte

1

and Yuliandri

2

1

Program Doktor Ilmu Hukum, Universitas Sumatera Utara (USU-Medan), Medan, Sumatera Utara, Indonesia

2

Program Doktor Ilmu Hukum, UniversitasAndalas (UNAND-Padang), Padang, Sumatera Barat, Indonesia

Keywords: Dispute; Electoral Justice; Legal pluralism, deliberation to reach a consensus.

Abstract: International Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) determines election justice to be one indicator of

democratic elections. Democratic countries are required to have a legal framework that is in line with the

country's system, especially instruments for electoral dispute resolution. The problem examined is how the

legal framework for electoral dispute resolution and the concept of upholding electoral justice related to

legal pluralism in Indonesia is evaluated by normative juridical methods. The results show that Indonesia

has already arranged the election process dispute (EPD) resolution. Election Supervisory Board (ESB) is

given the authority to complete EPDs whose decisions are final and binding. The adopted settlement

principle is deliberation to reach consensus. This model is new and closely related to the pluralism of the

Indonesian legal system. Consensus agreement is a living value system and codified in positive law (civil

law). However, it is necessary to revise the law to establish formal procedural law that is in accordance with

the principles of an effective and efficient election justice system. Furthermore, ESB's design and

transformation into a special court of character, strong and credible is needed.

1 INTRODUCTION

The main function of an election supervisory body is

to supervise the election process so that it runs

according to the legal rules and principles of the

election. For this reason, Bawaslu was formed as an

institution that works to prevent and enforce election

law.

In Law No. 7/2017, the term electoral disputes

and disputes was introduced. Typically, the term

dispute is known in civil law. But this law also

introduces two types of election process dispute

(EPD) resolution and disputes over election results.

SPP covers disputes that occur between election

participants and dispute between election

participants and election administrators as a result of

the issuance of the General Election Commission's

decision (Law No.7 / 2017, article 466). Election

Supervisory Board (ESB) as the election oversight

institution (EOI) is given the authority to complete

the EPD. Bawaslu's decision is final and binding

except for 3 (three) things, namely: verification of

political parties, determination of the list of

permanent candidates (LPC), and determination of

candidate pairs. These three things should have the

potential to cause election disputes, but why does the

law limit them that way. The concept of legal

settlement needs to be redesigned (reconstructed)

with a model of resolving election disputes that is

characterized, strong and trusted in order to realize

electoral justice.

2 METHOD

The study was conducted in northern Sumatra by

evaluating several cases that occurred in several

districts using the normative legal research method.

Data obtained from ESB of North Sumatra Province

in 2019 as in Table 1.

Table 1: The ESB data problems and solutions.

This case was handled by the ESB of North

Sumatra Province and 33 Regencies / Cities during

the simultaneous elections in 2019. Out of the 26

22

Munte, H. and Yuliandri, .

Legal Pluralism in Dispute Resolution on Election Justice.

DOI: 10.5220/0010294100003051

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Culture Heritage, Education, Sustainable Tourism, and Innovation Technologies (CESIT 2020), pages 22-27

ISBN: 978-989-758-501-2

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

submitted cases, there were one failed because they

were absent, 14 cases were resolved by closed

mediation mechanism and 11 cases were resolved by

open adjudication mechanism. The party who sued

was the legislative candidate and the management of

the political parties who felt disadvantaged because

they were not passed as candidates for the issuance

of the decision of the GEC. Data were analyzed

qualitatively against Law No.7 / 2017 and

International Institute for Democracy and Electoral

Assistance (IDEA) standards, then presented

systematically in the form of discussions to answer

the problem.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

3.1 Implementation of Election Dispute

Resolution

Based on case studies in various countries, there are

five law enforcement mechanisms for resolving

election disputes, namely (1) examinations by the

election management board the possibility of

appealing to higher institutions; (2) election court or

special judge to handle election complaints; (3)

general courts that handle objections with the

possibility of being appealed to higher institutions;

(4) the resolution of election problems is submitted

to the constitutional court and / or constitutional

court; and (5) resolution of election problems by the

high court. (Bisariyadi, 2012).

Election process disputes in the law stipulate that

the EPD covers dispute between participants and the

election organizer as a result of the issuance of GEC

decision. The law does not explain in more detail

about the definition of election disputes but only

describes the legal subjects of the election

participants and the GEC as a party. The object of

the dispute is in the form of a decision (beschikking),

legal actions of the subject and legal consequences

of the actions of the GEC.

The concept of this election dispute should be

clearly defined. According to the dictionary term, a

dispute is a conflict or dispute between two or more

parties to a certain object that causes legal

consequences or losses for one party. Election

disputes are disputes between two or more parties

regarding a thing or a violation of rights that are

detrimental to the interests or rights of election

participants due to the issuance of the GEC decision.

The application of legal settlement carried out by

EOI is carried out in two stages, namely the

mediation stage to reach consensus. However, if

mediation fails, an adjudication stage is carried out

to determine the final decision. In practice,

mediation works and many fails until adjudication.

Based on the decision data, this failure was caused

by each party holding their respective positions.

Referring to Cruz (De Cruz, P, 2014), norms can

be approached teleologically in the form of

sociological or economic demands (effective and

efficient). In this context the electoral process may

not be a violation or denial of the constitutional

rights of citizens by the government (GEC) and if it

occurs then it must be resolved. Election disputes

must be resolved according to the mechanism or

means available if there is a claim or complaint on

the rights of the injured citizens. The purpose of this

legal norm is in line with the concept of the rule of

law in accordance with the mandate of the Third

Amendment to the 1945 Constitution of the

Republic of Indonesia which states that the

Indonesian state is a state based on law.

According to JimlyAsshiddiqie, there are twelve

main principles of the rule of law and one of them is

the constitutional justice (JimlyAsshiddiqie, 2006).

The principle of state administrative justice is

answered by the existence of mechanisms and means

of administrative appeal in the law. The country is

represented by the GEC (central, provincial and

district / city) as a state administrative function in

the electoral field. The actions of state

administrative officials who are mistaken or wrongly

requested, corrected or monitored through the

administrative justice process. But there is still a

need to study so that ESB is considered appropriate

to be a means of electoral justice in overseeing the

GEC legal actions in the holding of elections.

Hart revealed that the law is an order from a

sovereign ruler and must be obeyed (Hart HLA,

1997). The law is a recognized order and must be

obeyed because it was formed by the sovereign

authority in Indonesia. The legislator gave the

mandate to order the central, provincial and district /

city ESBs to receive, examine and decide on

disputes in the electoral process that were submitted

to him.

Based on the data in Table 1, there were 14 cases

resolved in the mediation stage (consensus) and

there were 11 cases resolved during the adjudication

stage of the ESB decision. Looking at the data, one

side of mediation (consensus) is a useful tool for

justice seekers rather than continuing to an open

hearing. However, the 14 mediated cases prove that

the case sitting is not complicated and that there is

already a willingness / recognition of the GEC to

correct its mistakes. ESB only carries out procedural

Legal Pluralism in Dispute Resolution on Election Justice

23

and administrative mediation agreements only. The

results show that in the mediation process, the ability

and professionalism of a mediator must be

prominent and very decisive in mediating election

disputes.

The exercise of this authority has not yet been

equipped with standard procedural law in the context

of enforcing its material law. This is because there is

no firmness in the law related to the evidentiary law

in force (whether it refers to the proof of civil or

mixed law). The assertion of this norm is important

so what HLA said. Hart that primary (material) law

requires secondary law (formal law). The concept of

the law in question will have positive consequences

for the development of an electoral justice system

for the better.

3.2 Election Justice Enforcement

The Republic of Indonesia Constitution has

stipulated that elections must be held fairly and

fairly. There is no further explanation of what is

meant by fair (Refly Harun (2016). The law

governing the election is aimed at realizing fair and

integrity elections (Law No.7 / 2017). The third

paragraph mentioned that the holding of good and

quality elections will increase the degree of healthy

competition, participatory, and representation that is

getting stronger and can be accounted for. In this

study it was found that the explanation or definition

of good and quality election benchmarks must be

affirmed. There are three important processes of

electoral governance that go beyond just electoral

administration, namely the establishment of

regulatory bodies and rules, application of rules and

dispute resolution. Electoral governance begins with

the process of enacting laws and regulations, then

administrative enforcement and judicial assessment

(dispute resolution) and concludes when the process

returns to the beginning, either through judicial

interpretation or recommendations by the legislature.

(Torres And Díaz, 2014).

According to International IDEA, the electoral

justice is defined from the perspective of a fair and

timely election dispute resolution system. The

election justice in International IDEA's view is

limited to the realm of electoral legal problem

solving systems in the context of upholding citizens'

voting rights. Electoral justice includes the means

and mechanisms available in a particular country

that aims to:

A. Ensuring that each action, procedure and

decision are realted to the total process is in

line with the law (the constitution, statute law,

international instruments and treties, and all

other provisions); and

B. Protecting or restoring the enjoyment of

electoral rights, giving people who believe

their electoral rights have violated the ability

to make a complaint, get a hearing and receive

an adjudication. (Ayman Ayoub & Andrew

Elli, 2010).

As a reference for comparison, the limits made

by International IDEA are quite good and can be

applied. To maintain the credibility and legitimacy

of elections requires a system of electoral justice that

follows principles and values that originate from the

culture and legal framework of each country or

international legal instruments.

The system must run effectively and show

independence and impartiality to realize justice. In

this context, the electoral justice paradigm must

protect citizens' voting rights. If these rights are

manipulated, the electoral justice system must be

able to restore or restore it (Center for Electoral

Reform, 2010).

Ramlan Surbakti said not only limited election

justice to the availability of an electoral legal

framework, one important criterion was fair and

timely resolution of election disputes (Ramlan

Surbakti, 2014). The author agrees that the legal

system in force in the International can be adopted

but must adjust to the conditions, needs, values,

culture and legal system in the country. The system

that lives or is adhered to by the Indonesian people,

namely the values that exist in Pancasila.

In its implementation, the implementation of

electoral justice enforcement currently involves

numerous and scattered institutions. For example,

there is a GEC for election administration services, a

State Administrative Court for state administrative

disputes, a District Court for criminal acts, an

Election Organizer Honorary Board (EOHB) for

ethical violations, a Constitutional Court for disputes

over election results and finally there is an ESB for

administrative justice and election process disputes.

Scattered institutional variations and overlapping

authorities make dispute resolution long and

protracted. Several articles that clash, namely article

468 with articles 469, 470, 471 and article 472.

Comparing with the data collected, the ESB was

able to resolve disputes arising both in the mediation

and adjudication processes. The principle of one

forum can answer concerns about uncertainty and

the potential to reduce the principle of seeking fair

and timely elections. (Ady Thea DA, Variety of

Problems in Election Disputes). In this context

strengthening SPP in a strong and trusted institution

CESIT 2020 - International Conference on Culture Heritage, Education, Sustainable Tourism, and Innovation Technologies

24

is needed. The ESB can be transformed into an

electoral justice system to ensure fair and timely

resolution of election disputes. (InsiNantikaJelita,

2019).

3.3 SPP in Legal Pluralism Perspective

The settlement of the existing election case brings

the parties to the case together to be mediated. The

goal is to find a solution based on the deliberations

and consensus of the parties. This concept is quite

good because it reflects the value of living (living

law) that comes from Pancasila. Positive law (law

7/2017) absorbs and revitalizes noble values in

resolving conflicting general election laws.

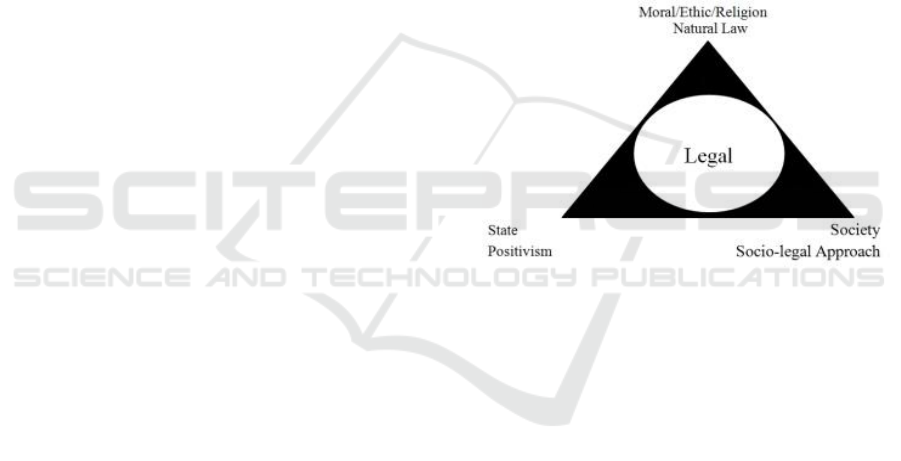

According to Werner Menski (Werner Menski,

2008) the three main types of approaches to the

triangular concept of legal pluralism are used: law

created by society, law created by the state and laws

arising through values and ethics of the nation

(AchmadAli , 2009). This view is supported by

Erman Rajagukguk who states that legal pluralism is

generally defined as a situation where there are two

or more legal systems that exist in a social life.

Legal pluralism as a characteristic of Indonesia

must be recognized as a reality of society. Each

community group has its own legal system which

differs from one another to the others such as in the

family, age level, community, political group, which

is a unity of a homogeneous society. With many

islands, tribes, languages and cultures, Indonesia

wants to build a stable and modern nation with

strong national ties. So, according to him, avoiding

pluralism is the same as avoiding different realities

about the perspective and beliefs that live in

Indonesian society. (M-1, Legal Pluralism Must Be

Recognized). Legal pluralism is characterized by the

existence of a variety of governing authorities, each

of whom requires compliance with the members or

citizens he governs. Legal pluralism is now widely

accepted and has seen a marked increase in interest

since the turn of the century, not least in light of its

broad range of perspectives on the state it seeks to

interpret and possess. (Benda-Beckmann and Turner,

2018). The global perspective on law and history

related to the legal tradition has become a dialectic

inherent in globalization, as well as several 'de-' and

're-traditionalisation' trends, often being

strengthened by law and becoming legal traditions

even more topical at the global level. (Duve, 2017).

Legal pluralism has become a fact of life for a long

time before the formation of the Indonesian state

itself.

To understand the law and the way to rule in

Asia, Werner Menski offers a legal pluralism

approach. Legal pluralism approach is an

interrelation between aspects of the state (positive

law), social aspects (socio-legal approach), and

moral / ethical / religious (natural law). The method

of law that only relies on positive law with rules and

logic and its rule bound only leads to a deadlock in

the search for substantive justice. The legal

pluralism approach as referred to by Menski is

illustrated in the manner shown in Figure 1. Based

on the exercise in Figure 1, it is found that the legal

world includes a large plurality of triangles in space

and time. Law is so plural, it is impossible to be

absorbed in a whole theoretical, but by itself

becomes a configuration in a simple model. Legal

pluralism is a perfect integration to understand and

enforce law in a plural society.

Figure 1: Legal Pluralism in Plural society.

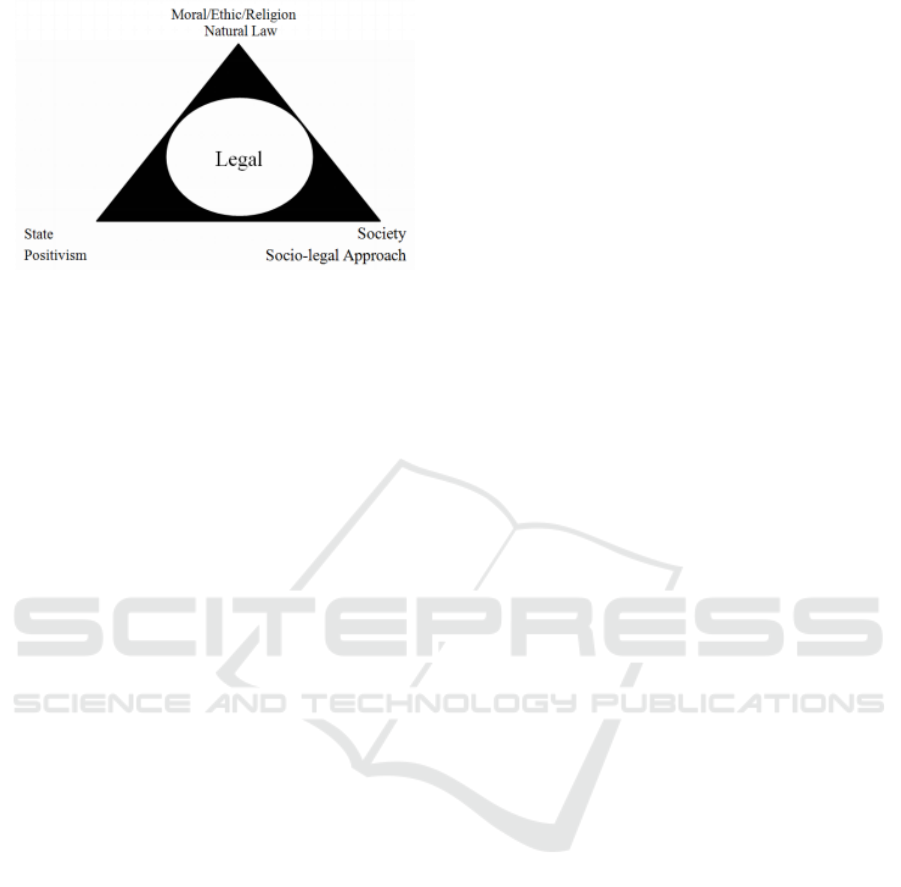

The legal pluralism approach in the form of a link

between positive law, socio-legal approach and

natural law is formulated in articles 466 - 469 of

Law 7/2017. The social aspect approach (socio-legal

approach) is taken from the cultural roots of

Indonesian people who are accustomed to

deliberation to reach a problem. This natural law

approach is reflected in the values of the four

precepts of Pancasila: democracy, wisdom of

wisdom in consultation / representation. By

borrowing the term Menski in the legal pluralism

approach, the paradigm of electoral dispute

resolution in Indonesia can be seen in Figure 2.

Legal Pluralism in Dispute Resolution on Election Justice

25

Figure 2: Pluralism-based paradigm of electoral dispute

resolution.

The opinion in the Figure 2 has strong relevance

underlying the legal norms in the dispute resolution

process. The goal is that the spirit of kinship and

mutual cooperation be maintained according to the

philosophy of the Pancasila rule of law. This

thinking concept is very suitable for the

implementation of fair and timely elections. In this

context the concept of deliberation and consensus is

actually ideal and suitable to be constructed as a

means of justice to correct or correct mistakes,

mistakes, violations and other election cases (except

criminal and election results). Correction mechanism

can be carried out for the stakeholders of the election

implementation both by election participants, GEC,

and the community. Errors or errors of procedures,

mechanisms, other administrative (except criminal

and the results of the vote) can be tested through the

means of electoral justice designed based on the

principle of dignified election means fair and timely.

The development of a dignified electoral justice

system is closely related to the philosophy of the

Indonesian state, namely creating a spirit of mutual

cooperation and the unity of Indonesia in wisdom

and wisdom. The paradigm that must be built is to

solve the problem not merely to try the case.

4 CONCLUSIONS AND

RECOMMENDATIONS

4.1 Conclusions

Based on the discussion results, the following

conclusions are drawn: The model of electoral

dispute resolution in Law 7/2017 with mediation

mechanism is highly needed but it is still

problematic in terms of mediator's capacity and

professionalism for the ESB members in resolving

election disputes. The concept of upholding electoral

justice by prioritizing deliberation and consensus is a

reflection of Indonesia's pluralism (volksgeist) but is

still problematic in terms of procedural law and

proof systems that are not yet standard.

4.2 Recommendations

In order to ensure election justice, articles 468, 469,

470, 471 and article 472 need to be revised by

reconstructing the dispute resolution process in one

forum on the ESB as well as standard evidentiary

laws. The draft and transformation of ESB is needed

to become a special judiciary that is characterized by

strong and trusted aspects to realize the electoral

justice system.

REFERENCES

Ali Achmad., 2009. “Menguak Teori Hukum (legal

theory) dan Teori Peradilan (Judicial prudence)”,

Vol.1, Kencana Pranamedia Group, pp.184-201.

Asshiddiqie, Jimly., 2006. “Konstitusi &

Konstitusionalisme Indonesia”, Sekretariatan Jendral

dan Kepaniteraan Konstitusi RI, Jakarta, pp. 154-161.

Ayman Ayoub & Andrew Elli., 2010. “Electoral Justice:

The International IDEA Handbook, International

IDEA, Stockholm, pp.1.

UU No.7/2017, pasal 466.

Benda-Beckmann Keebet von, Turner Bertram., 2018.

Legal pluralism, social theory, and the state, The

Journal Of Legal Pluralism And Unofficial Law, Vol.

50, N0. 3, Pages 255–274.

Berman Eli, et al., 2018. Election fairness and government

legitimacy in Afghanistan, Journal of Economic

Behavior & Organization Volume 168, Pages 292-

317.

Bisariyadi, et al., 2012. Komparasi Mekanisme

Penyelesaian Sengketa Pemilu di Beberapa Negara

Penganut Paham Demokrasi Konstitusional, Jurnal

Konstitusi, Volume 9, Nomor 3.

Centre for Electoral Reform (CETRO) (Penyunting).,

2010. ”Keadilan Pemilu: Ringkasan Buku Acuan

International IDEA”, Bawaslu RI, International IDEA,

dan CETRO, Jakarta, pp.5

De Cruz, P., 2014. “Perbandingan Sistem Hukum

Common Law, Civil Law, and Socialist Law”

Penerbit Nusa Media, Jakarta, pp. 384

Duve, Thomas., 2018. Legal traditions: A dialogue

between comparative law and comparative legal

history, Comparative Legal History Vol. 6, No. 1,

Pages 15–33.

Frank Richard W., et al., August 2017. How election

dynamics shape perceptions of electoral integrity,

Electoral Studies Volume 48, Pages 153-165.

Hart HLA., 1997. “The Concept of Law”, Claredon Press-

Oxford, pp. 36-68.

CESIT 2020 - International Conference on Culture Heritage, Education, Sustainable Tourism, and Innovation Technologies

26

Harun Refly., 2016. “Penyelesaian Perselisihan Hasil

Pemilihan Umum di Indonesia”, Disertasi, PDIH FH

Universitas Andalas, Padang, pp.21.

Huizenga Daniel, Governing territory in conditions of

legal pluralism: Living law and free, prior, and

informed consent (FPIC) in Xolobeni, South Africa,

Daniel Huizenga Mnwana, 2015 Mnwana et al., 2016

Kerr Nicholas., 2013. Popular evaluations of election

quality in Africa: Evidence from Nigeria, Electoral

Studies, Volume 32, Issue 4, Pages 819-837.

Menski Werner., 2008. “Perbandingan hokum dalam

konteks global: Sistem Eropa, Asia dan Afrika”,

Translated by M. Khozim, Nusamedia, Bandung, pp.

113-171.

Rosas Guillermo., 2010. Trust in elections and the

institutional design of electoral authorities: Evidence

from Latin America, Electoral Studies, Volume 29,

Issue 1, Pages 74-90.

Ramlan, Surbakti., 2014. ”Pemilu Berintegritas dan Adil”,

Kompas, 14 Februari, pp. 6.

Szablowski David., 2019. Legal enclosure” and resource

extraction: Territorial transformation through the

enclosure of local and indigenous law, The Extractive

Industries and Society Volume 6, Issue 3, Pages 722-

732.

Medina, Torres Luis Eduardo., Ramírez, Díaz Edwin

Cuitláhuac., 2014. Electoral Governance: More Than

Just Electoral Administration, Mexican Law Review,

Volume VIII (New Series), Number 1, Pages 34-46.

Antonio, Ugues Jr., et al., 2015. Public evaluations of

electoral institutions in Mexico: An analysis of the IFE

and TRIFE in the 2006 and 2012 elections, Electoral

Studies, Volume 40, Pages 231-244.

Daniel, Ziblatt., 2009. Shaping Democratic Practice and

the Causes of Electoral Fraud: The Case of

Nineteenth-Century Germany, American Political

Science Review, Volume 103, Issue 1, Pages 1-21.

UU No.7/2017, Lembaran Negara RI Tahun 2017 Nomor

182, Penjelasan

https://www.hukumonline.com/berita/baca/lt5c78f91c05c0

a/ragam-persoalan-dalam-sengketa-pemilu/ (accessed

26 April 2020)

https://www.hukumonline.com/berita/baca/hol15089/plura

lisme-hukum-harus-diakui/ (accessed 27 Februari

2020).

https://mediaindonesia.com/read/detail/252569-segera-

bentuk-peradilan-pemilu, (accessed 26 Juli 2020).

Legal Pluralism in Dispute Resolution on Election Justice

27