Evaluation of Safety Behavior and Work Environment of Operators

in the SME Producing Shuttlecocks

Issa Dyah Utami, Ika Deefi Anna, Trisita Novianti, Richo Dwi Cahyo

Department of Industrial Engineering, Universitas Trunojoyo, Madura, Bangkalan, Indonesia

Keywords: Safety behavior, work environment, small and medium enterprises.

Abstract: The role Small and Medium Enterprises in increasing the incomes and employment can certainly be rated for

Indonesia. The implementation of behavioral-based safety in SMEs in Indonesia is still very minimal, one of

which is the implementation at MM SME that produces shuttlecocks. The shuttlecock production processes

have not implemented a culture of work safety. Moreover, the working environment is still poor and work

standards are not applied. The application of Behavior-Based Safety (BBS) method in the research at MM

SME resulted in the values of safety behavior of 44% and unsafety behavior of 56%. The calculation of rating

indicates that the feather perforation process was unsafe. Unsafe production processes are recommended to

be improved by using the 5S method.

1 INTRODUCTION

Behavior-Based Safety (BBS) is a program to activate

employees in Occupational Health and Safety efforts.

Behavior-Based Safety strives to help management to

control unsafe work cultures in work areas that

involve operators or employees (Williams and Geller,

2000). The main cause of unsafety behavior and

unsafety conditions at work are the weaknesses in

management control that cannot be corrected only by

interfering unsafety behavior. The main purpose of

Behavior-Based Safety is to build the enthusiasm of

workers to observe if unsafety behavior occurs

directly in the workplace (Geller, 2005).

In Indonesia, the Behavior-Based Safety (BBS)

evaluation application as an effort to improve the

occupational safety and health system of employees

in small and medium enterprises (SMEs) has not

received much attention from the government and

researchers (Unnikrishnan et al., 2015; Ansori,

Sutalaksana and Widyanti, 2018)(Wang et al.,

2018)(Subramaniam et al., 2016; Subramaniam,

Mohd. Shamsudin and Lazim, 2016)(Abdullah et al.,

2016; Osman, Dhabi University Khalizani Khalid and

Mohsen AlFqeeh, 2019). This is not in line with the

conditions in which SMEs contribute more than 50%

to the economy in Indonesia. Therefore, this study

aims to evaluate the behavioral safety of one of the

SMEs in Indonesia that produces shuttlecocks. The

results of this study are expected to be an example and

increase the motivation of other SMEs in Indonesia in

implementing and improving their OHS system.

The MM SME is a SME engaged in the

manufacturing industry producing shuttlecocks

established in 2005. This SME produces 10 packs of

shuttlecock per day, in which one pack contains 50

boxes and one box contains 12 units of shuttlecocks,

meaning that MM SME can produce 6,000 units of

shuttlecocks each day. The production processes of

shuttlecocks have not implemented a culture of work

safety. The working environment is still poor and the

standards for work are not well-applied. The operator

of each machine at the MM SME still deals with

potential hazards that can cause accidents at the

workplace. The facilities and equipment to support

the tidiness of equipment and the cleanliness of the

workplace are not available. However, the types of

equipment available are brooms, trash bins, garbage

bins and shoe bins that are no longer suitable for use.

This causes ineffective and inefficient work

procedures and is risky for accidents in the workplace

because the products are various and high-quality.

Based on these problems, the research on the

prevention of occupational accidents by applying

health and safety culture, which covers Sort, Set in

Order, Shine, Standardize, and Sustain (5S) (Ghodrati

and Zulkifli, 2012; Agrahari, Dangle and Chandratre,

2015; Filip and Marascu-Klein, 2015; Sánchez et al.,

2015; Ankomah, Ayarkwa and Agyekum, 2017;

Adzrie et al., 2019) and minimizing risky behaviors

158

Utami, I., Anna, I., Novianti, T. and Cahyo, R.

Evaluation of Safety Behavior and Work Environment of Operators in the SME Producing Shuttlecocks.

DOI: 10.5220/0010305500003051

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Culture Heritage, Education, Sustainable Tourism, and Innovation Technologies (CESIT 2020), pages 158-164

ISBN: 978-989-758-501-2

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

by analyzing Behavior-Based Safety (BBS) approach

(Geller, 2005; Ismail, 2012; Persekutuan, 2015;

Skowron-Grabowska and Sobociński, 2018) needs to

be carried out.

2 RESEARCH METHOD

This research was conducted at the MM SME that

produces shuttlecocks. This study uses qualitative

methods through the CBC (Critical Behavior

Checklist) questionnaires, interviews and direct

observations. The questionnaires were distributed to

70 operators in the production area. The supporting

data of this research were obtained by collecting

information on work accidents and documentation in

the production area. The first step was identifying

unsafe behaviors. The identification table contains the

types of the production processes, the hazards, the

consequences of the potential hazards, the description

of the operators when working and the causes of

hazards. The stages in the CBC questionnaire include

assessing the aspects of the work environment,

namely floors, spatial planning, leakage prevention,

state of the facilities, and temperature. The equipment

and facilities include barriers and protectors, lifting

equipment, correct use, and the state of the

equipment. The personal protective equipment

comprises hand, face, eye, feet, fall, respiratory,

hearing and body protection equipment. The body use

and position include the eye safety at work and the

dangerous path. The aspects of the procedures consist

of work preparation, lock-out and tag-out.

The formula for calculating the safe score stated

by (Williams and Geller, 2000) is as follows:

%𝑆𝑎𝑓𝑒𝑡𝑦 𝑠𝑐𝑜𝑟𝑒

𝑇𝑆𝑂

𝑇𝑆𝑂 𝑇𝑅𝑂

100%

(1)

Note: TSO (Total Safety Observation) and TRO

(Total Risk Observation).

According to (Salem et al., 2007), the scoring and

calculation of unsafety behaviour rating numbers

indicate the range of values from 0 to 1, where the

security level is still in a safe condition, and vice versa

if it shows a range from 0 to (-1), and then classified

as unsafe condition. The formula (2) was used for the

rating calculation.

Rating =

∑

∑

∑

∑

(2)

Behavioral observation card was used to assess

the safety and danger of the operator's behavior in

carrying out the work and maintaining the work

environment. This research used Likert scale 1 to 5 as

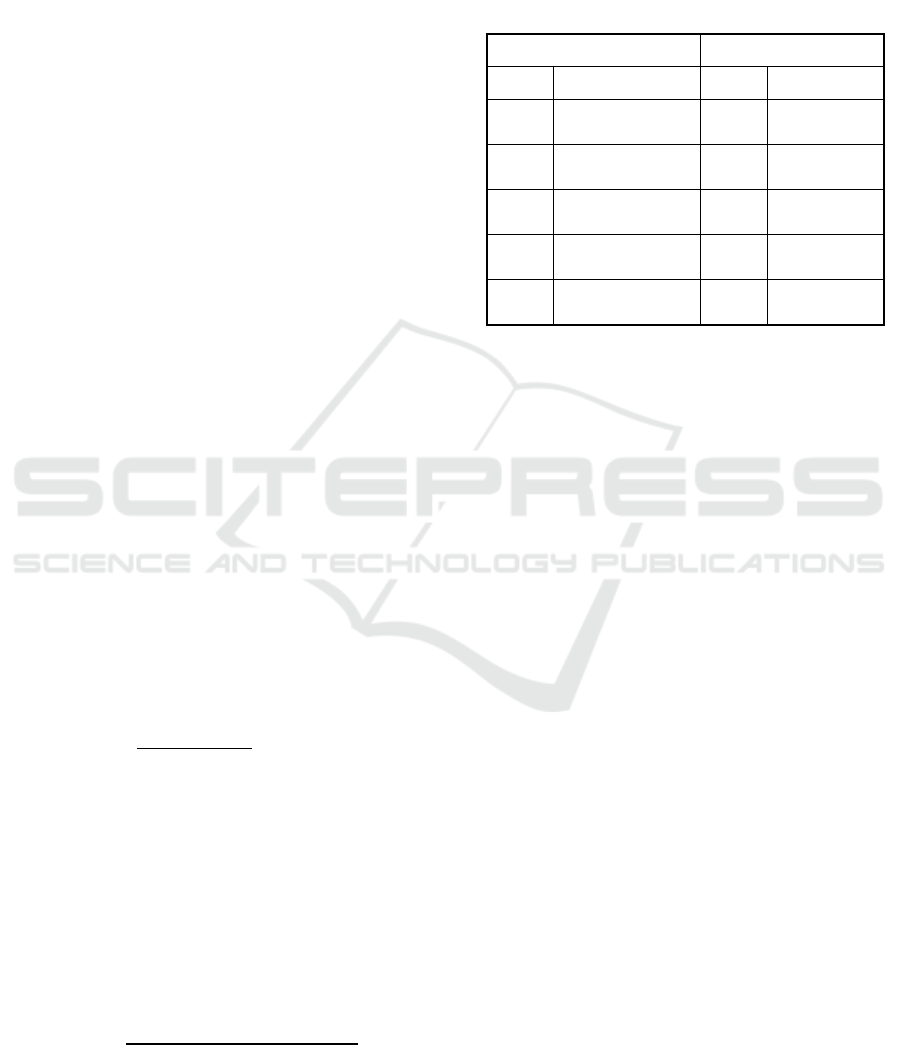

shown in Table 1.

Table 1: The assessment of safety and risk levels.

Safety Risk

Score Description Score Description

5

Very high

safet

y

5

Very high

hazar

d

4Hi

g

h safet

y

4

High

hazard

3Medium safet

y

3

Medium

hazard

2Low safet

y

2

Low

hazar

d

1Ver

y

low safet

y

1

Very low

hazar

d

The efforts to achieve an attitude become tangible

necessary supporting factors, and among others are

facilities. Facilities are resources to support safety

behaviors. It was found that the workplace in the MM

SME was not well structured. However, workers had

the desire to implement a good workplace

arrangement. These were proven in the results of

interview with an informant that he sorted goods,

returned goods to the workplace, cleaned the

workplace, and often had difficulty finding

equipment. The attitude of workers were still poor in

implementing a good workplace, and this was

evidenced by messy and disorganized condition of

workplace. Therefore, the efforts to improve the

workers’ behaviors can be conducted by structuring

the work environment using the following 5S

principles (Sort, Set in Order, Shine, Standardize, and

Sustain).

1. A brief design includes the method of selecting

materials and equipment that are used and not.

Critical Behavior Checklist is used to classify

equipment, materials, and objects that are in a

good condition, deformed, or damaged.

Equipment and objects that are not used are

also labelled with particular symbols.

2. Neat design involves the storing of equipment,

materials, and objects by disposing or placing

them in a storing place when they are no longer

used. They are stored based on the frequency of

use. The stored equipment and layout are given

labels.

3. The design of dress comprises several cleaning

phases involving workers’ participation.

Evaluation of Safety Behavior and Work Environment of Operators in the SME Producing Shuttlecocks

159

Partial cleaning involves the operators at the

production stations. It can be done by making

schedules, steps for cleaning, and procurement

of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE).

4. The design of care includes the stages of

maintaining and implementing the initial 3S

and making SOP (Standard Operating

Procedure) by taking into account the safety.

5. The design of diligent behavior includes the 5S

and SOP processing steps. Reward is granted

for those implementing the 5S principles and

SOPs, while punishment is given for the

violators of those regulations. Information on

OHS implementation is also continuously

provided.

3 RESULT AND DISCUSSION

This section describes the results of identification of

the unsafety behaviors applied by the MM SME

producing shuttlecocks, safety behavior index

calculation, rating and evaluation of the 5S (Sort, Set

in Order, Shine, Standardize, and Sustain) design.

The number of employees at MM is 100 people, with

71 production employees. Table 2 presents the

number of employees at each work station. All

employees in the production section became the

respondents in this study to provide information about

their behaviors at workplace by filling out the critical

behavior checklists. Table 3 demonstrates the

activities that cause unsafety behaviors in the shop

floor.

Table 2: The number of daily production operators.

No Work Station Operators

1

Feather selection and

oven 10

2 Feather perforation 10

3 Duck perforation 2

4 assembling 8

5 Stitchin

g

8

6 Controllin

g

6

7 Gluin

g

and dr

y

in

g

8

8 Testin

g

7

9 Packaging 12

Table 3: The identification of unsafety behaviors.

Process Shuttlecocks production

p

rocess

Hazar

d

Unprotected machinery

and equipment, slippery

floors, scattered items,

dust, chemicals, dirt, and

liquids

Exposure Infrequently

Deviation Operators do not wear

personal protective

equipment such as gloves,

masks, goggles, safety

shoes, and do not apply

cleanin

g

procedures, etc.

Consequence Wounds, sliced fingers,

shortness of breath, eye

pain, itching, eye irritation,

blisters, skin irritation,

faintin

g

, bruisin

g

, blisters

Cause Operators dot use PPE and

implemen

t

5S

Analysis on the information obtained from CBC

questionnaires on the behaviors of 10 operators in

feather selection station shows the following scores

of safety and risk levels, as presented in Table 4.

Table 4: The summary of responses to CBC questionnaires

on the behaviors of 10 operators in feather selection station.

Critical Behavior Checklists

in Feather Selection Station

Behavior REF. Safe At Ris

k

Work Environment 0 0 0

Spatial layou

t

1.1 25 37

Floo

r

1.2 23 31

Lighting 1.3 24 30

The condition of goods

and facilities

1.4 23 36

Temperature 1.5 25 30

Personal Protective

Equipment (PPE)

2 0 0

Eye protective

equipmen

t

2.1 25 29

Hand protective

equipmen

t

2.2 27 29

Respiratory

p

rotective

equipmen

t

2.3 25 33

Hearing

p

rotective

equipmen

t

2.4 30 30

CESIT 2020 - International Conference on Culture Heritage, Education, Sustainable Tourism, and Innovation Technologies

160

Foo

t

p

rotective

equipmen

t

2.5 30 30

Body

p

rotective

equipmen

t

2.6 29 31

Fall protective

equipmen

t

2.7 30 30

Equipment and

Facilities

3 0 0

Barrier equipment and

p

rotective equipmen

t

3.1 30 32

Lifting equipmen

t

3.2 29 30

The proper use of

equipmen

t

3.3 29 30

The condition of

equipmen

t

3.4 28 31

Bod

y

Use and Position 4 0 0

Eye safety at wor

k

4.1 30 30

Hazardous path 4.2 25 31

Procedures 5 0 0

Work preparation 5.1 30 31

Loc

k

-ou

t

/Tag-ou

t

5.2 30 30

Total 547 621

The calculation shows the safety score in the

feather selection station of 46%. This result implies

54% unsafety or potential of occupational accidents.

In terms of the measurement of unsafety behavior,

if the score ranges from 0 to 1, the condition is

considered safe, while if the score ranges from 0 to -

1, the condition is perceived unsafe.

Tables 5 and 6 demonstrate the identification

results of critical behaviors in feather perforation and

duck perforation.

Table 5: The summary of responses to CBC questionnaires

on the behaviors of operators in feather perforation station.

Critical Behavior Checklist in Feather

Perforation Station

Behavior REF. Safe At

Risk

Work

Environment 00 0

Spatial layou

t

1.1 23 37

Floo

r

1.2 22 30

Lighting

1.3 22 30

The condition

of goods and

facilities 1.4 19 38

Temperature

1.5 23 30

Personal

Protective

Equipment

(PPE) 20 0

Eye protective

equipmen

t

2.1 20 30

Hand

protective

equipmen

t

2.2 14 40

Respiratory

protective

equipmen

t

2.3 30 33

Hearing

protective

equipmen

t

2.4 30 30

Foo

t

p

rotective

equipmen

t

2.5 32 31

Body

protective

equipmen

t

2.6 30 32

Fall protective

equipmen

t

2.7 33 28

Equipment

and Facilities 30 0

Barrier

equipment and

protective

equipmen

t

3.1 19 32

Lifting

equipmen

t

3.2 29 30

The proper use

of equipmen

t

3.3 29 30

The condition

of equipmen

t

3.4 26

3

3

Bod

y

Use and

Position 40 0

Eye safety at

wor

k

4.1 30 30

Hazardous

p

ath 4.2 21 37

Procedures

50 0

Work

p

reparation 5.1 30 31

Loc

k

-ou

t

/Tag-

ou

t

5.2 30 31

Total

512 643

Evaluation of Safety Behavior and Work Environment of Operators in the SME Producing Shuttlecocks

161

Table 6: The summary of responses to CBC questionnaires

on the behaviors of operators in duck perforation station.

Critical Behavior Checklist in Duck

Perforation Station

Behavior REF. Safe At

Risk

Work

Environment 0 0 0

Spatial layou

t

1.1 6 6

Floo

r

1.2 6 6

Lighting

1.3 6 6

The condition of

goods and facilities 1.4 4 7

Temperature

1.5 8 6

Personal

Protective

Equipment (PPE) 2 0 0

Eye protective

equipmen

t

2.1 4 8

Hand protective

equipmen

t

2.2 4 6

Respiratory

protective

equipmen

t

2.3 4 7

Hearing

p

rotective

equipmen

t

2.4 6 7

Foo

t

p

rotective

equipmen

t

2.5 6 6

Body protective

equipmen

t

2.6 6 6

Fall protective

equipmen

t

2.7 6 6

Equipment and

Facilities 3 0 0

Barrier equipment

and protective

equipmen

t

3.1 6 7

Lifting equipmen

t

3.2 6 6

The

p

roper use of

equipmen

t

3.3 6 6

The condition of

equipmen

t

3.4 6 7

Bod

y

Use and

Position 4 0 0

Eye safety at wor

k

4.1 4 6

Hazardous path

4.2 6 6

Procedures

5 0 0

Work preparation

5.1 6 7

Loc

k

-ou

t

/Tag-ou

t

5.2 6 6

Total

112 128

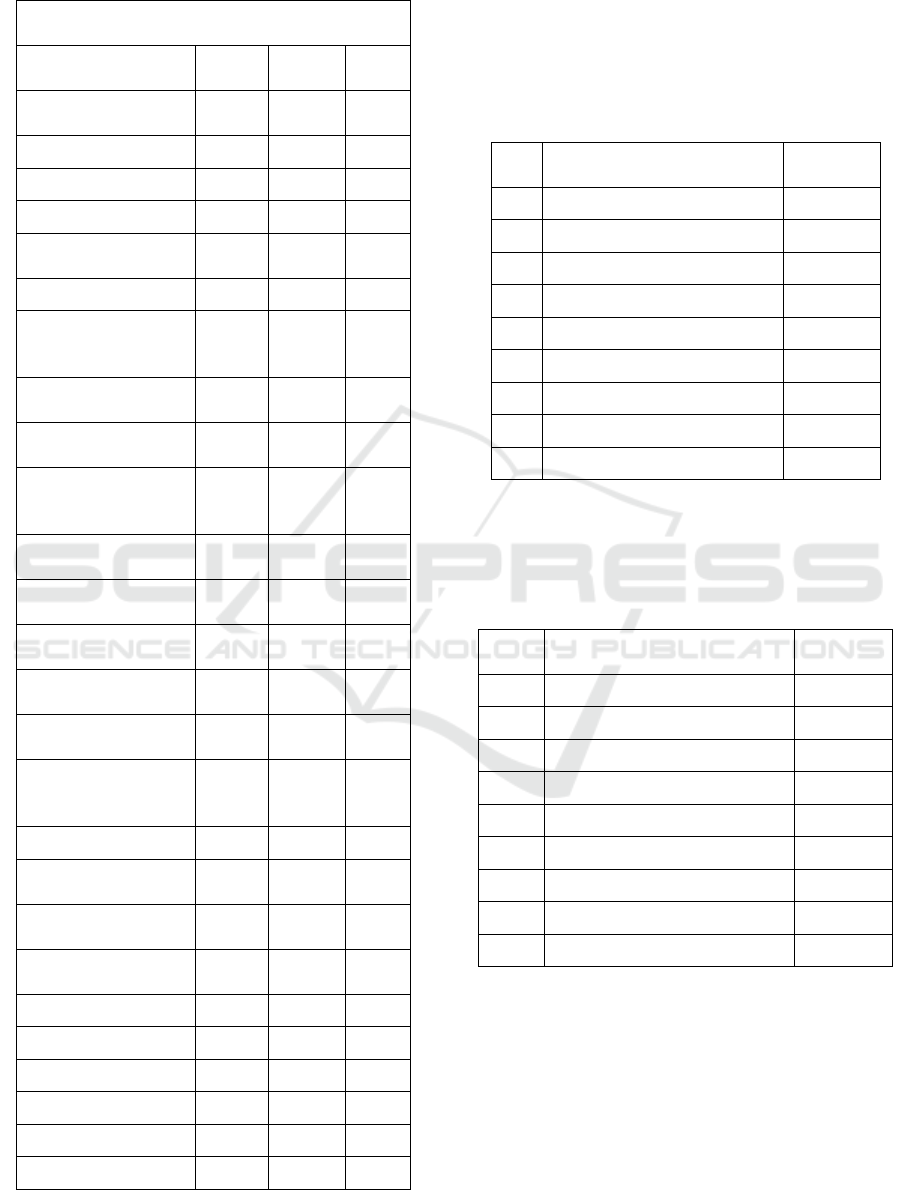

The summary of safety score calculation of the

results of observation on the nine processes in

producing shuttlecocks is presented in Table 7. The

safety score in the feather selection process was 46%,

denoting 54% potential of risky working condition

and behavior.

Table 7: Safety scores of nine processes.

N

o. Processes Safety

Score

1

Selection and feather oven 0.468322

2

Feather perforation 0.443290

3

Duck perforation 0.466667

4

Assemblin

g

0.568432

5

Stitching 0.530271

6

Controlling 0.603974

7

Gluin

g

and dr

y

in

g

0.491886

8

Testin

g

0.553687

9

Packa

g

in

g

0.452684

The summary of scoring calculation on safety and

unsafety behaviors of workers in each process of

production is demonstrated in Table 8.

Table 8. The summary of rating scores.

No. Shuttlecock Production

Processes

Ratin

g

1

Feathe

r

selection and oven -0.1191

2

Feather perforation -0.2036

3

Duck perforation -0.1245

4

Assembling 0.31671

5

Stitching 0.12874

6

Controlling 0.52403

7

Gluing and drying -0.0319

8

Testing 0.24019

9

Packaging -0.1728

The ratings of behaviors in feather selection,

feather perforation, duck punching, gluing and

packaging processes ranged from 0 to -1; and thus,

the conditions were classified unsafe. The unsafe

production processes were then further evaluated for

improvement using the 5S principles of health and

safety culture (Sort, Set in Order, Shine, Standardize,

and Sustain).

CESIT 2020 - International Conference on Culture Heritage, Education, Sustainable Tourism, and Innovation Technologies

162

The results of 5S evaluation were yielded after the

calculation of safety and unsafety rating scores at

each production process. The processes include father

selection, feather perforation, duck perforation,

gluing and packaging. The activities of operators in

applying 5S and SOP procedures were observed by

the person in charge in each station.

Work safety procedures set in the MM SME

Guidance regulate that operators must use Personal

Protective Equipment (PPE), comply with OHS

(Safety, Health and Work), apply 5S, report and

document unsafety conditions to superiors, be honest

and attend OHS briefings. The briefing is held every

Monday before the production process starts. The

activity aims to provide various information to

operators, including OHS, compliance with SOP and

5S, potential hazards and how to overcome them, the

latest OHS issues, etc. It is usually conducted in five

to 15 minutes and all operators are required to attend.

The Personal Protective Equipment used in the

MM SME includes:

a. Clothes protective equipment

This equipment protects the body from liquid,

dust, and dirt. Some of the equipment are apron

clothes from fabric or leather and waterproof

clothes from parachute that can be used in

humid work place.

b. Hearing protective equipment

It functions to prevent noise resulted from

machines. The equipment is commonly made

of rubber, hard plastic, soft plastic, wax, and

cotton.

c. Eye and face protective equipment

It is commonly made of plastic and functions to

shields eye and face from small materials, heat,

light, and radiation.

d. Respiratory protective equipment

This equipment protects nose and mouth, as

well as respiratory system from pollution at

work place.

e. Hand protective equipment

It protects fingers of exposure to fire, heat,

chemicals, radiation, scratches, and collisions.

This equipment to shield hands from heat and

fire is made of asbestos, cotton, and wool.

Equipment to protect wound and scratches is

made of leather. Synthetic materials are used

for chemical hazards.

f. Foot protective equipment

The equipment protects toes and soles of feet

from being hit by hard objects, liquid spills,

tripping, and slips, being punctured by objects,

the hazards of hot water, dirt, and cold. Shoes

are made of plastic or synthetic rubber, and

leather with a rough surface.

Socialization and information are provided in the

forms of pictures or posters so that operators and

others will notice and understand them more easily.

4 CONCLUSION

Identification of potential hazards was done at each

shuttlecock production station by examining the data

of accidents. In the process of feather selection, the

danger was from hot objects and equipment used in

the feather curing. Direct contact with hot equipment

could cause the palm to bend if operator did not

implement the 5S principles. The feather perforation

process with sharp knives could endanger the

operators. The 5S principles were not applied so that

the operators were vulnerable to finger-cuts. The

results of identifying unsafety behavior were

evaluated using the SBI (Safety Behavior Index)

(Mohammad, Zuraida and Esmail, 2018) calculation.

SBI values in the feather selection process, the feather

perforation process, the duck perforation process, and

tide process were 0.468, 0.443, 0.466, and 0.568,

respectively. Meanwhile, the SBI values in the

sewing process, the service process, the gluing and

drying process, the test process and the packaging

process were 0.53, 0.603, 0.491, 0.533, and 0.452,

respectively. The SBI results that were more than

50% or 0.50 indicated the implementation of safety

behaviors. The rating calculation showed the unsafe

production processes, where the values in the feather

selection, feather perforation, duck perforation,

gluing, and packaging processes were -0.119, -0.203,

-0.124, -0.031, and -0.172, respectively, denoting

negative values as represented by 0 to -1 scores.

The evaluation of improvements was carried out

with the 5S principles by examining the production

processes and the result showed that the processes

were considered fairly unsafe. Therefore, a short

design was made by selecting equipment and items

needed. The equipment and items that were not

required in the processes were given red labels. Neat

design was created by organizing and storing items

according to the frequency of use. Name labels and

storage areas, such as toolboxes, cabinets, and small

shelves, were provided. Dresses were designed by

making cleaning schedules and rules, including time,

cleaning tools used, and responsibilities. The

procurement of PPE (Personal Protective Equipment)

was performed by considering the needs of operators.

The design of care was made by setting SOP

(Standard Operating Procedure) of 5S and PPE so that

Evaluation of Safety Behavior and Work Environment of Operators in the SME Producing Shuttlecocks

163

the 5S principles could be applied earlier. Salary was

designed by customizing the SOPs, giving

punishment to SOP violators, and granting rewards to

SOP implementers. The information was announced

by using pictures, posters, and weekly briefing to

discuss about OHS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research publication was funded by the Faculty

of Engineering, Universitas Trunojoyo Madura.

REFERENCES

Abdullah, M. S. et al., 2016. ‘Safety Culture Behaviour in

Electronics Manufacturing Sector (EMS) in Malaysia:

The Case of Flextronics’, Procedia Economics and

Finance. Elsevier B.V., 35(October 2015), pp. 454–

461. doi: 10.1016/s2212-5671(16)00056-3.

Adzrie, M. et al., 2019. ‘Implementation of 5s in Small and

Medium Enterprises ( SME )’, 1(1), pp. 1–18.

Agrahari, R. S., Dangle, P. A. and Chandratre, K. V., 2015.

‘Implementation Of 5S Methodology In The Small

Scale Industry A Case Study’, International Journal of

Scientific & Technology Research, 4(4), pp. 180–187.

Ankomah, E. N., Ayarkwa, J. and Agyekum, K., 2017. ‘A

theoretical review of Lean implementation within

construction SMEs’, 6th International Conference on

infrastructure development in Africa, (April), pp. 71–

83..

Ansori, N., Sutalaksana, I. Z. and Widyanti, A.., 2018.

‘Comparison Between Key Success Factors in Safety

Behavior in Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises

(SMEs) and Large Industries, and Development of a

Hypothetic Model for Safety Behavior in Indonesian

SMEs’, KnE Life Sciences, 4(5), p. 582. doi:

10.18502/kls.v4i5.2587.

Filip, F. C. and Marascu-Klein, V., 2015. ‘The 5S lean

method as a tool of industrial management

performances’, IOP Conference Series: Materials

Science and Engineering, 95(1). doi: 10.1088/1757-

899X/95/1/012127.

Geller, E. S., 2005. ‘Behavior-based safety and

occupational risk management’, Behavior

Modification, 29(3), pp. 539–561. doi:

10.1177/0145445504273287.

Ghodrati, A. and Zulkifli, N., 2012. ‘A Review on 5S

Implementation in Industrial and Business

Organizations’, IOSR Journal of Business and

Management (IOSR-JBM), 5(3), pp. 11–13.

Ismail, F., 2012. ‘Steps for the Behavioural Based Safety:

A Case Study Approach’, International Journal of

Engineering and Technology, 4(5), pp. 594–596. doi:

10.7763/ijet.2012.v4.440.

Mohammad, A., Zuraida, A. and Esmail, J. M.., 2018. ‘A

Conceptual Framework for Upgrading Safety

Performance by Influence Safety Training,

Management Commitment to Safety and Work

Environment: Jordanian Hospitals’, International

Journal of Business and Social Research, 8(7), pp. 25–

35. doi: 10.18533/ijbsr.v8i7.1117.

Osman, A., Dhabi University Khalizani Khalid, A. and

Mohsen AlFqeeh, F., 2019. ‘Exploring the Role of

Safety Culture Factors Towards Safety Behaviour in

Small-Medium Enterprise’, International Journal of

Entrepreneurship, 23(3), pp. 1939–4675.

Persekutuan, W., 2015. ‘Level of Awareness on Behaviour-

Based Safety ( Bbs ) in Manufacturing Industry

Towards Reducing Workplace Incidents’, 3(1), pp. 77–

88.

Salem, O. et al., 2007. ‘A behaviour-based safety approach

for construction projects’, Lean Construction: A New

Paradigm for Managing Capital Projects - 15th IGLC

Conference, (July), pp. 261–270.

Sánchez, P. M. et al., 2015. ‘Impact of 5S on quality ,

productivity and organizational climate - Two Analysis

Cases’, Proceedings of the 2015 International

Conference on Operations Excellence and Service

Engineering, (Cura 2003), pp. 748–755.

Skowron-Grabowska, B. and Sobociński, M. D., 2018.

‘Behaviour Based Safety (BBS) - Advantages and

Criticism’, Production Engineering Archives, 20(20),

pp. 12–15. doi: 10.30657/pea.2018.20.03.

Subramaniam, C. et al., 2016. ‘The influence of safety

management practices on safety behavior: A study

among manufacturing smes in Malaysia’, International

Journal of Supply Chain Management, 5(4), pp. 148–

160.

Subramaniam, C., Mohd. Shamsudin, F. and Lazim, M.,

2016. ‘Safety Management Practices and Safety

Compliance: A Model for SMEs in Malaysia’, in The

European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural

Sciences, pp. 856–862. doi:

10.15405/epsbs.2016.08.120.

Unnikrishnan, S. et al., 2015. ‘Safety management practices

in small and medium enterprises in India’, Safety and

Health at Work. Elsevier Ltd, 6(1), pp. 46–55. doi:

10.1016/j.shaw.2014.10.006.

Wang, Q. et al., 2018. ‘Analysis of Managing Safety in

Small Enterprises: Dual-Effects of Employee Prosocial

Safety Behavior and Government Inspection’, BioMed

Research International. Hindawi, 2018. doi:

10.1155/2018/6482507.

Williams, J. H. and Geller, E. S., 2000. ‘Behavior-Based

Intervention for Occupational Safety: Critical Impact of

Social Comparison Feedback’, Journal of Safety

Research, 31(3), pp. 135–142. doi: 10.1016/S0022-

4375(00)00030-X.

CESIT 2020 - International Conference on Culture Heritage, Education, Sustainable Tourism, and Innovation Technologies

164