Multiple Intelligences: Does It Offer a New Assistance in Encouraging

Students’ Reading Comprehension Skill?

Yuni Putri Utami

Universitas Bahaudin Mudhary Madura

Keywords: multiple intelligences, reading comprehension

Abstract: Teaching strategies of multiple intelligences was believed to assist learners to obtain a better understanding

of their potential intelligences and interests in enhancing their learning process. Thus, the primary objective

of this research is to investigate the types of Multiple Intelligences affecting reading comprehension skills

since it could be as a medium of reading comprehension strategies. A 50-item reading TOEFL test and a 90-

item multiple intelligences questionnaire test were issued among 50 male and female students at Bahaudin

Mudhary Madura University. This study was quantitative research by using questionnaire. The research data

were analysed using a multiple regression analysis. Three instruments were occupied and it consisted of

TOEFL-Longman PBT Test, a TOEFL reading subtest, and MI questionnaire. Mckenzies (1999)

questionnaire was administered to assess the participants’ intelligence profile. It consisted of 9 intelligences

types proposed by Gardner (1999) and 10 statements of each criterion. The result indicated: 1) there were

significant effects among MI types toward reading comprehension skills since the sig value was 0.017, 2)

the musical, interpersonal, kinaesthetic, have significant influence toward reading comprehension and it was

believed to be predictors of reading comprehension skills since the musical intelligences has the sig value

0.015, kinaesthetic intelligence has the sig value 0.011, and the least powerful predictors are interpersonal

intelligences which has the sig value 0.044.

1 INTRODUCTION

Over the past few decades, research in the field of

learning has led to the discovery of the theory of

multiple intelligences (Herndon, 2018). In other

words, this theory states that each person has

different ways of learning and different intelligences

they used in their daily lives. Some can learn very

well in a linguistically-based environment e.g.

reading and writing but others are better taught

through mathematical-logic based learning. While

others are benefit most from body-kinaesthetic

intelligence.

Most educators have positively responded to

Gardner’s theory. It has been embraced by a range

of educational theorists and significantly, applied by

teachers and policymakers to the problems of

schooling. In any classroom setting from preschool

to college, students learn differently. Each student is

gifted and challenged by his or her learning abilities

and preferences (Sulaiman et al., 2010). A concept

in the classroom setting may be a new skill,

knowledge, or some combination of both.

Practitioners such an educator teaches his or her

students based on the background knowledge they

have, build upon what was learned yesterday, last

week, or even last year. Repeating a lesson on a

concept improves learning as the teacher pulling

from the theory of multiple intelligences can

reinforce the learning with different types of

activities.

According to Jackson, (2020) repeating exposure

to learning concepts is important, however using the

same teaching method to teach concepts causes

students to lose focus. There are times when the

worksheet is the best method to provide practice for

learning a concept, but relying on worksheet every

day for every lesson can cause some learners to tune

out. Thus teaching to the multiple intelligences

allows the teacher to keep the learning environment

fresh by changing up the teaching method. In short,

mixing up the teaching methods keeps students

interested in the lesson. By using a variety of

teaching strategies across the multiple intelligences,

the teacher can assess or measure students learning.

In regard to this, investigating the types of multiple

Utami, Y.

Multiple Intelligences: Does It Offer a New Assistance in Encouraging Students’ Reading Comprehension Skill?.

DOI: 10.5220/0010306900003051

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Culture Heritage, Education, Sustainable Tourism, and Innovation Technologies (CESIT 2020), pages 243-248

ISBN: 978-989-758-501-2

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

243

intelligences as a medium of reading comprehension

became the main focus in this research.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Theoretically, Multiple Intelligences (MI) was

proposed by Gardner in the 1980 triggering a change

of definitive idea of intelligence and the stance

regarding to a very bounded notion of intelligence

(Roohani et al., 2015). Some experts believed that

intelligence is a monolithic innate agent that could

be evaluate over IQ tests. However, Gardner (I983)

defined intelligence as pluralistic construct that

consisted of numerous competence. According to

Gardner (1999), intelligence can be activated

through bio-psychological potential for information

processing in a cultural setting to maintain problems

or create products which are useful in a culture. He

defined distinctive kinds of intelligences and

perceived intelligence as a composite of the diverse

outside interdependent set: linguistic, logical-

mathematical, spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, musical,

interpersonal, intrapersonal, and naturalist.

MI theory has been adopted and widespread by

many practitioners for the 1980s. Generally, MI can

have numerous sequences for education (Armstrong,

2009; Hoerr, Boggeman, & Wallach, 2010), and

specifically, language pedagogy, (Christison, 1996;

Simpson, 2000; Tahriri & Yamini, 2010). It can

consider to students’ individual diversity, particular

fascinate, and necessity, and it can engage the

teachers facilitate students with the educational

exercises created consisting to their preliminary

criterion (Armstrong, 2009). Moreover, it can be

accustomed to distinguish discovering aptitude of

various language learners (Tahriri & Yamini, 2010)

and generate differential consideration in language

learning (Haley, 2004). The views of MI theory on

learners’ difference in intelligence profiles provide

teachers’ more precise authentication of student’s

analytical skills aimed to have exceed bearing their

inabilities (Armstrong, 2009).

In contrast to conventional approaches to

intelligence that were basically focusing on the

whole notion of intelligence, Gardner (1983)

confound a complete circumstance of those inactive

theory of intelligence and declared that all learners

are born with an utmost dispose of aptitude and

capabilities through which some are inherently

dynamic and some are delicate in each learner.

Garnet (2005) simplify that such distinctiveness do

not unavoidably attain individuals smarter than one

another, but rather accept their being clever in

difference ways. Gardner (1983) suggested that

human brain is aimed to proceed multiple diverse

forms of learning styles applied to as Logical-

Mathematical, Musical-Rhythmic, Interpersonal,

Intrapersonal, Verbal Linguistic, Bodily-Kinesthetic,

and Naturalist. Afterward, he added the capability of

Existential-Spiritual Intelligence that was not fully

measured in his list. Through those exposition,

Gardner (2006) asserts that intelligences be

evaluated fiercely that are intelligent-fair and

incredibly that investigate the intelligence

immediately rather than over the lens of linguistic

or logical-mathematical intelligences

(Modirkhamene, 2012).

Many studies investigated MI theory and

considered it as effective strategies to increase the

student’s performance. Dolati and Tahriri, (2017) on

their paper ‘EFL Teachers’ Multiple Intelligences

and Their Classroom Practice’ explained that overall

the participants lack of knowledge about MI theory

and accordingly didn’t attempt to administer it in

their English classes. Besides, it was demonstrated

that teachers with specific kinds of MI have the

aptitude to use activities alike their foremost type of

intelligence.

Likewise to main point of MI theory, educators

need to approach topics over numerous key points

and arrange time for students to immerse in self-

reflection, assume self-paced work, deals with

variety distinctive passages or connect their

particular experience and feelings to the material

being studied. They must frequently change methods

from linguistic to musical, from spatial to bodily-

kinaesthetic, constantly connected intelligences in

innovative way. Educators pursuing to employ

multiple intelligences theory in their classrooms

need to figure out their students’ strengths,

weaknesses, and their linking of intelligences

associate to deliver substantial learning experiences

for them (Gardner, 2016).

Another study conducted by Ahvan and Pour,

(2016) revealed an evidence in which every person

possesses multiple intelligences has distinctive types

of intelligence with difference levels of each. This

study confirmed that almost students’ intelligence

was verbal linguistic, while the musical intelligence

was an infrequently intelligence. Some factors

triggered those result such as the chances, context

attainable for the sustenance of intelligence, were

quite feasible since verbal-linguistic intelligence

might have evolved due to the context acquirable to

it. Whereas, musical and other intelligences might

have persist underdeveloped or kindly elaborated

since fostering context was not accessible to them.

CESIT 2020 - International Conference on Culture Heritage, Education, Sustainable Tourism, and Innovation Technologies

244

Agreeably to MI theory, each person retains nine

intelligences and employs them to achieve

distinguish kinds of tasks. Yet, intelligence

improvement relied on personal, context, and other

factors (Vongkrahchang & Chinwonno, 2016)

.

Some experts believed that MI strategies can

assist learners to acquire their knowledge since this

theory suggested nine types of learning style. Each

learner is unique and has their learning style. In

regard to this, it was expected this strategies also has

significant effect toward reading comprehension.

Reading is one of the four skills that plays important

role in educated society (Roe & Smith, 2012: 1-2). It

is a literacy skill that gives a fundamental

contribution to cognitive development. The activity

of reading needed a high concentration and focus.

Students can learn to read more easily than they can

acquire any other skills. It is a source of great

pleasure for people all over the world. Through

reading people can be informed and can increase

their understanding of the globe. Reading is not only

aimed at providing information and pleasure to the

reader, but it also helps extend one’s knowledge of

the language. Non-native speakers of English can

use reading materials as the primary source of input

as they learn the language. They not only gain rapid

and easy access to the historical and cultural

conventions of English native speakers but to the

real and live language as well (Reza et al., 2016).

Meanwhile, reading in a foreign language, in

particular, is more challenging because the act of

reading is complex and demanding on the brain. It is

not just someone learning to read in another

language; rather, L2 reading is a case of learning to

read with languages (Grabe, 2009). Generally,

individuals vary in the way they process

information. For example, some students prefer

studying in groups and like to discuss information

with others whereas others learn better in an

independent setting. However, it seems to be

impossible for students, as adults, to always work in

their preferred mode (Vongkrahchang &

Chinwonno, 2016).

A number of EFL studies have demonstrated the

relationship between vocabulary knowledge and

reading comprehension performance (Hamzehlou et

al., 2012). Further, it was stated that vocabulary

knowledge is fundamental in reading comprehension

because it functions as identical as background

knowledge in reading comprehension. Vocabulary

knowledge facilitates decoding, which is a

significant part of reading.

3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This research employed 50 students male and female

of Bahaudin Mudhary Madura University as the

research participant. The participants were all adult

learners ranging in age from 18-25 years old. Three

instruments were occupied and it consisted of

TOEFL-Longman PBT Test, a TOEFL reading

subtest, and MI questionnaire. TOEFL PBT test was

administered to check the homogeneity of the

participants. A multiple choice TOEFL test was

administered to the participants to measure their

reading comprehension ability. It consisted of 50

questions including 50 reading comprehension

items. Mckenzies (1999) questionnaire was

administered to assess the participants’ intelligence

profile. This questionnaire consisted of 9

intelligences types proposed by Gardner (1999) and

it contains 10 statements of each criteria.

The data were analysed by investigated the mean

and standard deviation of the TOEFL scored. The

reading comprehension subs-test of a TOEFL test

was used to evaluate reading comprehension skill of

the participants. Lastly, the Mckenzie questionnaire

was applied to identify the learners’ intelligence

profile. Each participant was required to complete

the questionnaire by placing 0 or 1 next to each

statement. Number 1 meant it corresponded to the

learner while number 0 indicated that it did not

correspond to them. Two separate multiple

regression analyses were run to find out which

multiple intelligence types are better predictors of

reading comprehension skills.

4 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSIONS

The first question attempted to find out which types

of multiple intelligences are predictors of reading

comprehension. A multiple regression was used to

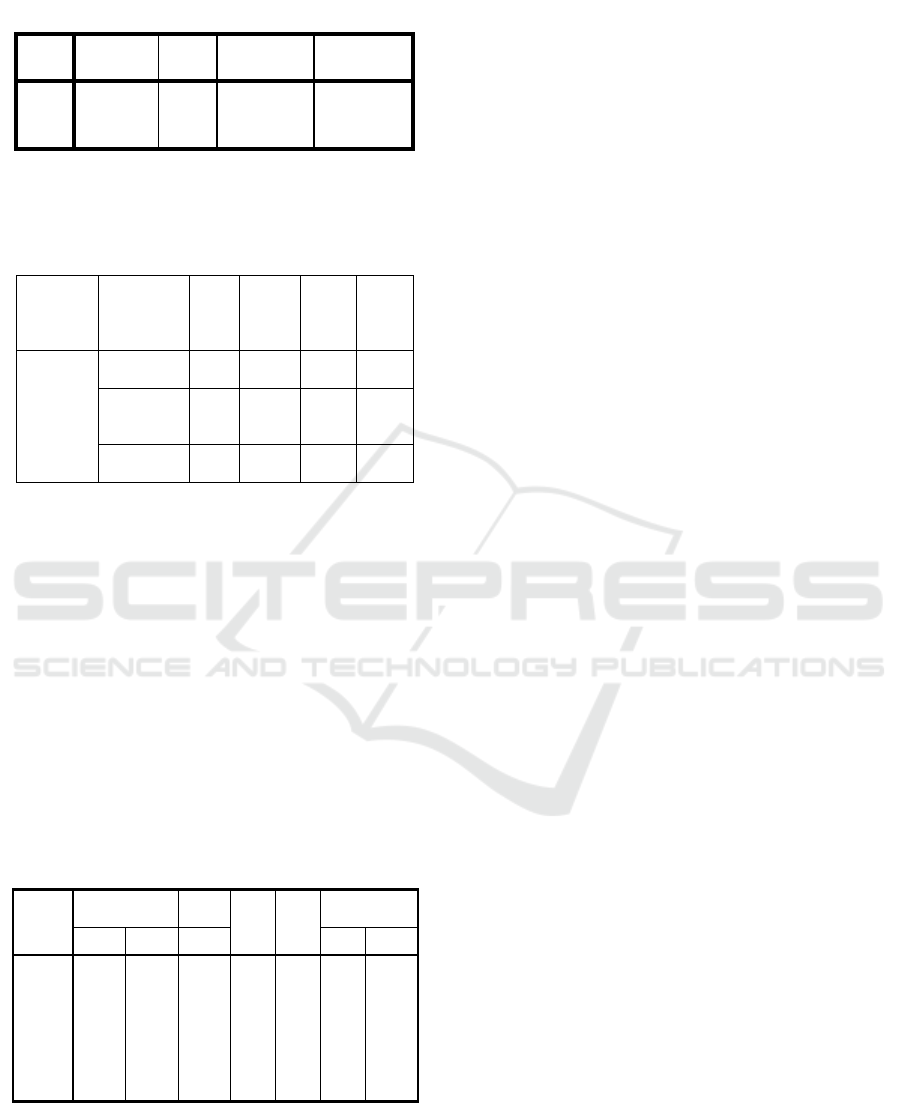

get the data. Table 1 describes how much variance is

disclosed by all the nine predictors entered into the

regression equation.

The results give us a clear explanation about how

much variance in reading comprehension. Based on

the table, all intelligence types’ collective account is

23% of the variance in reading comprehension.

Meanwhile, Table 2 explained the results of the

ANOVA. The ANOVA tests the null hypothesis that

predictive power of the model is not significant.

Multiple Intelligences: Does It Offer a New Assistance in Encouraging Students’ Reading Comprehension Skill?

245

Table 1. Model Summary

Table 2. ANOVA of Reading Comprehension Test

Model Sum of

Squares

D

f

Me

an

Squ

are

F Sig

.

Regress

ion

Residua

l

Total

2115.14

6

9 235.

016

2.64

3

.017

b

3556.85

4

40

88.9

21

5672.00

0

49

a. Dependent Variable: reading

b. Predictors: (Constant), visual, existential, interpersonal, natural,

kinesthetic, verbal, intrapersonal, logical, musical

Based on the ANOVA result, the significant

value (p) was 0.017. It was lower than the sig. level

(0.05). Since it was less than the sig. level, it meant

that there were significant effects among the MI

types toward reading comprehension skills.

To find out how much of the variance in reading

comprehension is accounted for by each of the nine

predictors, the standardized coefficients and the

significance of the observed t-value for each

predictor were analysed. The results are summarized

in Table 3.

Table 3. Coefficients of Multiple Intelligences

As Table 3 shows, among of all the nine

predictors, musical, interpersonal, and kinaesthetic

intelligences is indicated statistically significant of

the variance in reading comprehension. Among

these three intelligence types, kinaesthetic

intelligence is the best predictor of reading

comprehension since the sig value is 0.011. This is

closely followed by musical intelligence which has

the sig value 0.015 and the least powerful predictors

are interpersonal intelligences which has the sig

value 0.044.

Furthermore, based on the finding this research

examined which MI types that have affected reading

comprehension skills. The result found there were

three types of MI that assist reading such as musical

intelligence, kinaesthetic intelligence, and

interpersonal intelligence. Since reading has a strong

connection with vocabulary items. Vocabulary

knowledge is a complex construct that involves the

acquisition of multiple word knowledge components

(Henriksen 1999; Read 2000; Nation 2013; Schmitt

2014). However, most of our current understanding

about this construct derives from studies that have

assessed only one type of word know- ledge,

especially the form–meaning link (Melka 1997;

Milton and Fitzpatrick 2014a). As a consequence,

the construct of vocabulary knowledge as a whole is

still largely unexplored, and it is unclear how the

different word knowledge components are acquired

and fit together (Milton and Fitzpatrick 2014b;

Schmitt 2014).

Experts classified vocabulary knowledge into 4

dimensions. The first dimension is multiword

expression. It is defined as Many word bundles

occur in texts more frequently than would be

expected by chance (Biber, Conrad, & Cortes, 2004;

Hyland, 2012). Reading research in which text is

manipulated to include or exclude multiword

expressions shows that the occurrence of these

expressions impacts comprehension, even

controlling for the frequency of words used in the

passages (Martinez & Murphy, 2011). These finding

indicated that vocabulary knowledge is connected

with reading comprehension. The second dimension

is topical associates. It can be inferred the way to

understand the similarities across words to establish

categories. Indeed, some researchers have

understood vocabulary knowledge primarily as

network building (Haastrup & Henriksen, 2000) and

have even suggested that there is no difference

between knowing a word well and having a rich

lexical network related to that word (i.e., there is no

distinction between vocabulary depth and breadth;

Vermeer, 2001).

The next is hypernyms. A hypernym is a

superordinate general term that subsumes a set of

specific hyponyms. For instance, dog is a hypernym

to poodle, terrier, and mutt. Collins and Quillian

Coefficients

a

Model

Unstandardized Coefficients

Standardized

Coefficients

t Sig.

95.0%

Confidence Interval

for B

B Std. Error Beta

Lower

Bound

Upper

Bound

1. (Constant) 20.306 11.545 1.759 .086 -3.027 43.639

natura

l

.525 .674 .108 .779 .440 -.837 1.888

musica

l

-4.740 1.865 -.380 -2.541 .015 -8.510 -.970

existential 2.618 1.659 .236 1.578 .122 -.735 5.971

interpersonal 1.294 .622 .311 2.080 .044 .037 2.551

logical -.382 1.411 -.038 -.270 .788 -3.234 2.470

kinesthetic 2.361 .882 .358 2.677 .011 .578 4.144

verbal .217 1.385 .022 .157 .876 -2.582 3.017

intrapersonal 2.515 1.911 .195 1.316 .196 -1.348 6.377

visual 1.835 1.316 .189 1.394 .171 -.826 4.496

a. Dependent Variable: reading

Model Summary

Model R

R

Square

Adjusted R

Square

Std. Error of

the Estimate

1

.611

a

.3

73

.232 9.42981

a. Predictors: (Constant), visual, existential,

interpersonal, natural, kinaesthetic, verbal,

intrapersonal, logical, musical

CESIT 2020 - International Conference on Culture Heritage, Education, Sustainable Tourism, and Innovation Technologies

246

(1969) argued that our mental lexicon is stored in

hypernym chains (animal > dog > poodle). In a

follow-up study, Johnson-Laird (1983) hypothesized

that subjects respond faster to adjacent higher-order

hypernyms (dog-animal) than to adjacent lower-

order hypernyms (dog-poodle) but was unable to

confirm the hypothesis. Understanding a word’s

superordinates (i.e., that the word is an instance of a

broader category) may be a component of word

knowledge that influences lexical processing and

may explain variance in reading comprehension.

Lastly is definition knowledge. Unlike the other

kinds of word knowledge described here,

definitional knowledge involves both understanding

something about a word and understanding

something about a very unique academic genre. It is

difficult to understand definitions, and children can

easily misinterpret or misapply them. On the one

hand, it has been amply demonstrated that

definitions are hard to interpret, so providing

children with a definition alone is not sufficient to

ensure that they have an accurate representation of a

word and how it is used (Miller & Gildea, 1987;

Scott & Nagy, 1997). On the other hand, the

combination of a definition with contextualized

exposures to a word results in richer word learning

(Bolger, Balass, Landen, & Perfetti, 2008; Gardner,

2007). For our purposes, the most relevant studies to

date examined the extent to which additional

variance in students’ reading comprehension was

explained by performance on a definition task, after

controlling for their knowledge of the word’s

synonyms (Ouellette, 2006; Cain & Oakhill, 2014).

These studies suggested that understanding a word’s

definitions explains additional variance in reading

comprehension, although in these cases, latent

scores were not used to model the relationships

between these collinear predictors.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Regarding to the research finding, a number of

points may be concluded. First, the findings indicate

that musical intelligence is the best predictor for

reading comprehension that has the sig. value 0.015.

Since musical intelligence involves the ability to

sing, and to understand the vocabulary and use

rhythm, it can be concluded that the inclusion of

poems and songs should facilitate reading

comprehension.

Second, kinaesthetic intelligence turned out to be

significantly affected reading comprehension which

has sig value 0.011. Although people with this type

of intelligence understand things better when they

are physically involved with something rather than

reading or listening about it. Learners with this type

of intelligences have a high awareness of balance,

position, momentum, and stationary presence.

Besides, they usually follow their gut instincts and

do not like to be told what to do.

Third, Interpersonal intelligence positively

influence the learners’ reading comprehension skills.

Interpersonal intelligence is the ability to understand

and interact effectively with others. It involves

effective verbal and nonverbal communication, the

ability to note distinctions among others, sensitivity

to the moods and temperaments of others, and the

ability to entertain multiple perspectives. It has to be

a good predictor for reading comprehension skills

since the type of intelligence has the sig value of

0.044.

In addition, since reading and vocabulary

mastery triggered with only three and four of the

intelligences, respectively, activities could be

incorporated in the classroom to activate only the

right kind of intelligence to improve the learning

conditions. In short, the findings of the present study

can help teachers to obtain a clear understanding of

MI theory and its applicability in a pedagogical

context. Teachers can find new ways of teaching to

consider their learners' need as well as their

intelligence profiles. The present study may also

have implications for material developers and

syllabus designers. They should develop materials

and course books to improve the specifications of

MI types as predictors of language learning.

REFERENCES

Armstrong, T. (2009). Multiple intelligences in the

classroom, 4

th

edition. USA: ASCD

Ahvan, Y. R. and Pour, H. Z. (2016) ‘The correlation of

multiple intelligences for the achievements of

secondary students’, 11(4), pp. 141–145. doi:

10.5897/ERR2015.2532.

Biber, D., Conrad, S., & Cortes, V. (2004). If you look

at…: Lexical bundles in university teaching and

textbooks. Applied Linguistics, 25(3), 371–405.

Bolger, D., Balass, M., Landen, E., & Perfetti, C. (2008).

Context variation and definitions in learning the

meanings of words: An instance-based learning

approach. Discourse Processes, 45(2), 122–159.

Cain, K., & Oakhill, J. (2014). Reading comprehension

and vocabulary: Is vocabulary more important for

some aspects of comprehension. L’Année

Psychologique, 114, 647–662.

Multiple Intelligences: Does It Offer a New Assistance in Encouraging Students’ Reading Comprehension Skill?

247

Christison, M. A. (1996). Teaching and learning languages

through multiple intelligences. TESOL, 6(1), pp. 10-

14.

Collins, A. M., & Quillian, M. R. (1969). Retrieval time

from semantic memory. Journal of Memory and

Language, 8(2), 240–247.

Dolati, Z. and Tahriri, A. (2017) ‘EFL Teachers ’ Multiple

Intelligences and Their Classroom Practice’. doi:

10.1177/2158244017722582.

Gardner, H. (2016) ‘John dewey's educational theory and

educational implications of howard gardner ’ s’, 4(2).

Doi: 10.5937/ijcrsee1602057a.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind. New York: Basic

Books

Gardner, H. (1999). Intelligence reframed. New York:

Basic Books

Gardner, H. Moran, S. (2006). The Science of Multiple

Intelligences Theory: A response to Lyn Waterhouse.

Educational Psychologist, 41 (4), 227-232

Haastrup, K., & Henriksen, B. (2000). Vocabulary

acquisition: acquiring depth of knowledge through

network building. Vigo International Journal of

Applied Linguistics, 10(2), 221– 240.

doi:10.1111/j.1473-4192.2000.tb00149.x

Haley, (2004). Learner – Centered Instruction and the

Theory of Multiple Intelligences With Second

Language Learners. Teachers College Record 106 (1).

163-180

Hamzehlou, S., Zainal, Z. and Ghaderpour, M. (2012)

‘Knowledge with Professional Practice A Review on

the Important Role of Vocabulary Knowledge in

Reading Comprehension Performance’. The Authors,

66, pp. 555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.11.300.

Haastrup, K., & Henriksen, B. (2000). Vocabulary

acquisition: acquiring depth of knowledge through

network building. Vigo International Journal of

Applied Linguistics, 10(2), 221– 240.

doi:10.1111/j.1473-4192.2000.tb00149.x

Henriksen, B. 1999. ‘Three dimensions of vo- cabulary

development,’ Studies in Second Language

Acquisition 21: 303–17

Herndon, Eve. (2018). What are multiple intelligences and

how do they affect learning?.

https://www.cornerstone.edu/blog-post/ Feb, 06 2018.

Hyland, K. (2012). Bundles in Academic Discourse.

Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 32, 150–169.

doi:10.1017/s0267190512000037

Jackson, J. Eric. (2020). How Does the Multiple

Intelligence Theory Help Students?

https://education.seattlepi.com/ 22 Oct. 20

Martinez, R., & Murphy, V. A. (2011). Effect of

frequency and idiomaticity on second language

reading comprehension. TESOL Quarterly, 45(2),

267–290. doi:10.5054/tq.2011.247708

Melka, F. 1997. ‘Receptive vs. productive aspects of

vocabulary,’ in N. Schmitt and M. McCarthy (eds):

Vocabulary: Description, Acquisition and Pedagogy.

Cambridge University Press.

Miller, G. A., & Gildea, P. M. (1987). How children learn

words. Scientific American, 257(3), 94–99

Milton, J. and T. Fitzpatrick. 2014a. Dimensions of

Vocabulary Knowledge. Palgrave Macmillan.

Milton, J. and T. Fitzpatrick. 2014b. ‘Introduction:

Deconstructing vocabulary knowledge,’ in J. Milton

and T. Fitzpatrick (eds): Dimensions of Vocabulary

Knowledge. Palgrave Macmillan.

Modirkhamene, S. (2012) ‘The Effect of Multiple

Intelligences-based Reading Tasks on EFL Learners’

Reading Comprehension’, Theory and Practice in

Language Studies, 2(5), pp. 1013–1021. doi:

10.4304/tpls.2.5.1013-1021.

Nation, I. S. P. (2013). Learning vocabulary in another

language (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Ouellette, G. P. (2006). What’s meaning got to do with it:

The role of vocabulary in word reading and reading

comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology,

98(3), 554–566. doi:10.1037/0022-06

Read J. (2000). Assessing vocabulary. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press

Reza, A., Tabrizi, N. and Noor, P. (2016) ‘Multiple

Intelligence and EFL Learners’ Reading

Comprehension’, Journal of English Language

Teaching and Learning Tabriz University, (18).

Roohani, A., Mirzae, A. and Poorzangeneh, M. (2015)

‘Effect of Multiple Intelligences-Based Reading

Instruction on EFL Learners’ Reading Comprehension

and Critical Thinking Skills’, Iranian Journal of

Applied Linguistics (IJAL), 18(1), pp. 167–200.

Schmitt, N. (2014). ‘Size and depth of vocabulary

knowledge: What the research shows,’ Language

Learning 64: 913–51.Scott & Nagy, 1997

Sulaiman, T., Abdurahman, A. R., & Rahim, S. S. A.

(2010). Teaching strategies based on multiple

intelligences theory among science and mathematics

secondary school teachers. Procedia - Social and

Behavioral Sciences, 8, 512–518.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.12.070

Vermeer, A. (2001). Breadth and depth of vocabulary in

relation to L1/L2 acquisition and frequency of input.

Applied Psycholinguistics, 22(02), 217–234

Vongkrahchang, S., & Chinwonno, A. (2016). Effects of

Personal Intelligence Reading Instruction on Personal

Intelligence Profiles of Thai University Students.

Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 37(1), 7–14.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjss.2016.01.007

CESIT 2020 - International Conference on Culture Heritage, Education, Sustainable Tourism, and Innovation Technologies

248