The Psychological Safety of the Educational Environment of Ukrainian

Higher Education Institutions in a Pandemic: Empirical Data of a

Comparative Analysis of Participants’ Assessments Studying Online

Olena I. Bondarchuk

1 a

, Valentyna V. Balakhtar

2 b

, Yuriy O. Ushenko

2 c

, Olena O. Gorova

1 d

,

Iryna M. Osovska

2 e

, Nataliia I. Pinchuk

1 f

, Nataliia O. Yakubovska

2 g

,

Kateryna S. Balakhtar

1,2 h

and Maksym V. Moskalov

1 i

1

University of Educational Management, 52A Sichovykh Striltsiv Str., Kyiv, 04053, Ukraine

2

Yuriy Fedkovych Chernivtsi National University, 2 Kotsiubynskyi Str., Chernivtsi, Ukraine, 58012

Keywords:

Psychological Safety, Participants of the Educational Process, Pandemics, Coronavirus Disease 2019,

Educational Environment, Distance Learning.

Abstract:

This paper highlights the problem of ensuring the psychological safety of participants of the educational pro-

cess in the mass transition to distance learning, caused by the complex conditions of our time and the specific

features of the digital environment in the COVID-19 pandemic. The study demonstrates the results of a com-

parative analysis of students’ assessments studying online in a pandemic, the peculiarities of the psychological

safety of the educational environment and its impact on students studying online in a pandemic. Also, this

paper reveals the insufficient tendency to decrease the level of psychological safety of the educational envi-

ronment for a significant number of subjects. There are statistically significant differences in the peculiarities

of the psychological safety of participants in the educational process as to gender, age, and status. The survey

of participants in the educational process presents the results as to their attitude to the peculiarities of learning

under the conditions of the COVID-19. They testify to the deterioration of psychological safety in the educa-

tional environment of higher education institutions, and, accordingly, the subjective well-being of participants

in the educational process in a pandemic. There was a decrease in the number of respondents with a positive

attitude to distance learning and a willingness to work exclusively online. The study displays the expediency

of full-time and distance learning as such, which is optimal for the organization of the educational process and

contributes to the psychological safety of participants in the educational process.

1 INTRODUCTION

Today’s challenges, voluntary social isolation, uncer-

tainty, stress, and the threat to health caused by the

spread of COVID-19 (Velykodna, 2021) have shifted

people’s emphasis in public, social, professional, sci-

entific, educational, and religious life toward online

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3920-242X

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6343-2888

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1767-1882

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9022-3432

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8109-658X

f

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1904-804X

g

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2391-6188

h

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9154-9095

i

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3213-9635

services (Tkachuk et al., 2021).

These and many other difficult life situations ne-

cessitate adaptation to new conditions and expect spe-

cial requirements for their safety at all levels of life.

Thus, educational institutions around the world have

switched to distance learning to create safe conditions

for students and necessary measures for a full-fledged

educational process in connection with the COVID-

19 pandemic (Velykodna and Frankova, 2021). Ac-

cording to UNESCO with an increasing number of

states, provinces and even whole countries closing in-

stitutions of learning as a response to the COVID-19

pandemic, almost 70% of the world’s students are not

attending school (Commonwealth of learning, 2020).

Changing the traditional (full-time) form of dis-

tance learning has revealed gaps, problems, anxiety,

14

Bondarchuk, O., Balakhtar, V., Ushenko, Y., Gorova, O., Osovska, I., Pinchuk, N., Yakubovska, N., Balakhtar, K. and Moskalov, M.

The Psychological Safety of the Educational Environment of Ukrainian Higher Education Institutions in a Pandemic: Empirical Data of a Comparative Analysis of Participants’ Assessments

Studying Online.

DOI: 10.5220/0010920100003364

In Proceedings of the 1st Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology (AET 2020) - Volume 1, pages 14-31

ISBN: 978-989-758-558-6

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

unpreparedness for such, unexpected challenges in

users of social networks.

Forced distance learning requires not only the or-

ganization of the educational process in quarantine

and the use of traditional teaching methods but also to

provide specific resources for e-learning, master in-

formation tools and be able to use them depending

on the understanding of the goal so that each person

feels psychologically protected (safe) in the modern

Internet environment and in general in the informa-

tion space. Therefore, the problem of the psycholog-

ical safety of a person who studies online in a pan-

demic becomes especially relevant.

Psychological safety is a kind of safety awareness

based on the psychological climate of the educational

process in educational institutions (Ming et al., 1504,

pp. 433-440). This is especially important in times of

social changes, the rapid development of information

technology, and the possibility of using various means

of influencing human consciousness. In this context,

a psychologically safe educational environment is a

condition for the personal growth of the participants

of the educational process through their interaction,

independent from the manifestations of psychologi-

cal violence; reference significance and involvement

of each subject in designing and maintaining the psy-

chological comfort of the educational environment; a

humanistic orientation, etc (Bondarchuk, 2018b).

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Psychological safety is a basic need for safety, “a

kind of sense of confidence, safety and freedom

that removes fear and anxiety, in particular, it con-

tains a feeling that a person meets current and future

needs” (Maslow et al., 1945, pp. 21-41). Psycho-

logical safety involves the reduction of interpersonal

risk, which necessarily accompanies uncertainty and

change (Schein and Bennis, 1965; Siemsen et al.,

2009), readiness to “get a job or express oneself phys-

ically, cognitively and emotionally during role perfor-

mances”, the ability to “refuse and defend one’s per-

sonal” (Kahn, 1990, pp. 692-724).

Nowadays complex conditions and the specific

features of the digital environment in the COVID-19

pandemic, which is a favourable basis for psycholog-

ical violence, cyberbullying, manipulative influences,

caused the problem of psychological safety of partici-

pants in the educational process in the mass transition

to distance learning, which attracts particular atten-

tion. In particular, a new form of bullying – cyberbul-

lying is a form of behaviour that consists in sending

messages of an aggressive and offensive nature us-

ing new information and communication technologies

(Internet, and mobile phone). There are many factors

and theories of bullying, the most famous of which is

the sketch theory of (Olweus, 2004, pp. 5-17), where

the existence of typical characteristics of “victim” and

“aggressor”.

Other forms of cyberbullying are the “hacking”

actions aimed at harming the “victims”’ personal

computers (hacking and changing passwords, damag-

ing personal websites, etc.). All these damages deter-

mine the presence of specific features of such “high-

tech” bullying in comparison to a traditional one.

Firstly, constant hostile actions are inessential, as,

for example, one-time damage to the victim’s website

with the addition of offensive information may have a

longitudinal effect (many network users will read the

message).

Secondly, the factor of physical strength, impor-

tant in cases of ordinary (contact) bullying, is insignif-

icant. The intellectual abilities and technical skills of

the aggressor come to the fore in this case.

Thirdly, there is no direct communication between

the “aggressor” and the “victim”. So the “aggres-

sor”, for example, does not observe the reaction of

his/her “victim” and the outcomes of the actions. Bul-

lying via the Internet allows the “aggressor” to remain

anonymously and turn the situation of persestageion

into a kind of “masquerade” (Hinduja and Patchin,

2010, pp. 206-221).

Therefore, the psychological safety of all the par-

ticipants in the educational process studying online in

a pandemic is a prerequisite for their psychological

well-being and psychological health.

We single out such scientific investigations of re-

cent years, which together with the above serve theo-

retical and methodological basis for research.

We have developed the conceptual provisions on

the content of the psychological safety of the indi-

vidual in general (Edmondson, 1999; Edmondson and

Lei, 2014; Gartner, 2019) and its role in the process

of knowledge exchange in virtual communities, in

particular (Commonwealth of learning, 2020). We

consider safety as a key psychological characteristic

of the educational environment (Baeva, 2020), while

the psychologically safe educational environment as

a condition for the personal growth of the participants

of the educational process through their interaction,

independence from the manifestations of psycholog-

ical violence; reference significance and involvement

of each subject in designing and maintaining the psy-

chological comfort of the educational environment; a

humanistic orientation, etc.

The research examines the specifics of psycholog-

ical safety as one of the most important factors of

The Psychological Safety of the Educational Environment of Ukrainian Higher Education Institutions in a Pandemic: Empirical Data of a

Comparative Analysis of Participants’ Assessments Studying Online

15

work in the virtual environment (Edmondson, 1999;

Breuer et al., 2016; Goller and Laufer, 2018; Ro-

zovsky, 2015).

The following study has analysed: the features

of distance learning under the conditions of self-

isolation as to the COVID-19 pandemic (Bailey-

Findley, 2019); the peculiarities of the use of di-

verse digital educational resources and online learn-

ing tools in the educational process (Kartashova et al.,

2018; Bondarenko et al., 2018); the specifics of

the organization of effective work of remote virtual

teams online (Pilar and Middlemiss, 2019; Shyshk-

ina and Marienko, 2020), management aspect in dis-

tance learning (Kapucu and Salih, 2020, pp. 8-27);

the possibility of obtaining the psychological safety

in such teams (Congelos, 2020; Costello, 2020) and

approaches of ensuring the psychological safety in a

crisis (Clark, 2020).

Besides, most students and teachers of higher

education institutions had little experience with on-

line tools, information technology before the SARS-

CoV-2 (COVID-19 [coronavirus disease 2019]) pan-

demic. Today’s challenges have caused a shock in

society – a threat to human health from COVID-19,

economic downturn, the transition to distance learn-

ing, job losses, social support, business closures and

more.

Distance learning is not the same as online learn-

ing. Real online learning takes place on digital plat-

forms designed for this purpose, often with person-

alized content for each student and options for using

their chosen digital tools. Online learning promotes

different types of learning preferences, provides flex-

ibility and uses quality indicators online. But under

COVID-19, distance learning for the student commu-

nity did not include any of these functions but instead

provided a set time to listen to teachers’ lectures via

Zoom or Google Meet (Weir, 2020, p. 54). Moreover,

pre-coronavirus online training programs may not be

as effective without the support of teachers and a per-

sonal learning structure.

The teaching staff needs pedagogical support for

distance learning and proper education on the systems

used and preparation of the content of academic dis-

ciplines (Kapucu and Salih, 2020; Shokaliuk et al.,

2020), mastering new technologies and their use in

parallel with their previous experience and beliefs

(Hinduja and Patchin, 2010; B

¨

uy

¨

ukbaykal, 2015).

After all, digital competence is now an essential

competence that modern man needs for personal re-

alization and development, employment, social in-

tegration and active citizenship (European Commis-

sion, 2018; Moiseienko et al., 2020; Kuzminska et al.,

2019).

In Ukraine, scholars are currently conducting the

research, which relates mainly to psychological care

and psychotherapeutic practice in a pandemic in var-

ious spheres of public life (Kremen, 2020). For in-

stance, the well-known scientific work “The world of

life and psychological safety of human under condi-

tions of social change”, carried out by a team of scien-

tists led by M. Slyusarevsky at the Institute of Social

and Political Psychology during 2000-2017, which

contains extremely valuable scientific results. How-

ever, authors of the work naturally could not predict

the course of events related to the COVID-19 pan-

demic and, accordingly, conduct basic research in this

aspect, the results, in particular, determine the ways of

the rise of the individual’s psychological safety under

the conditions of social changes.

Despite numerous studies, the problem of psycho-

logical safety of the educational environment in gen-

eral and students studying online in a pandemic, in

particular, attracts attention. As a result, the desire

for safety is a basic human need, an important factor

in the self-realization of the individual in professional

and personal life and a condition for a full life of the

individual (Ryan and Deci, 2001).

Consequently, the most important goal of the ed-

ucational institutions is to ensure the psychological

safety of the educational environment for students

studying online in a pandemic, integrating the effec-

tive use of ICT in the educational process, updating

the psychological and pedagogical science. At the

same time, it is essential to fully promote the change

of education for a sustainable future by strengthen-

ing critical thinking, communication, cooperation and

creativity in youth (Semerikov et al., 2020).

The goal of the article is to present the features of

the psychological safety of the educational environ-

ment and their impact on students studying online in

a pandemic. Objectives of the study – to find out:

1) peculiarities of psychological safety of the educa-

tional environment for participants of the educa-

tional process online;

2) participants’ attitudes in the educational process

(students and teachers) to the peculiarities of

learning under the conditions of the COVID-19

pandemic;

3) to carry out a comparative analysis of students’ as-

sessments studying online in a pandemic regard-

ing the change of the psychological safety of the

educational environment of higher education in-

stitutions

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

16

3 METHODS

For studying the features of the psychological safety

of the educational environment and their impact on

students studying online in a pandemic, was the

method of I. Baeva “Psychological safety of the ed-

ucational environment” (Baeva, 2020) modified by

O. Bondarchuk (Bondarchuk, 2018b,a), which al-

lowed measuring the level of psychological safety of

the individual in the educational environment.

The author’s questionnaire carried out the study

of the peculiarities of the psychological safety of the

educational environment for the participants of the

educational process and their attitude to the features

of learning under the COVID-19 pandemic condition.

Afterwards, the respondents answered the questions

on various aspects of learning, such as:

1. Does the educational institution contribute to your

psychological safety under the conditions of the

COVID-19?

2. Is distance learning comfortable for you?

3. What form of training is optimal for you?

4. What information tools do you use in the edu-

cational process in the context of the COVID-19

pandemic? etc.

The empirical study implemented online through

Google Forms. This allowed prompting feedback

from participants in the educational process. From

our previous work experience, Google Forms “not

only determines the nature of the relationship be-

tween the participants of the educational process and

the degree of satisfaction with them, and the socio-

psychological climate as an indicator of organiza-

tional culture but also makes the appropriate manage-

ment decisions and forecast situations in the educa-

tional environment; promptly intervenes and makes

appropriate adjustments to the educational process;

specifically, plans work on the relevant problem in

the institution of higher education; creates condi-

tions for comparing one’s assessment of the pedagog-

ical staff’s activity with an independent assessment”

(Bondarchuk et al., 2020) and surveys the level of this

influence.

The usage of Google Forms and other information

and communication resources in education allows you

to: easily and quickly adapt to new requirements of

distance education; monitor the quality of education;

create an optimal environment for educational ser-

vices; and understand human behaviour in the social

environment, life cycles and interactions between bi-

ological, psychological, social-structural, economic,

political and cultural factors of the educational pro-

cess (Balakhtar, 2018, pp. 93-104).

There is the widespread usage of Google Forms

for conducting various surveys, including for testing

the level of knowledge acquisition; as a test platform,

and test results are stored in the Google Cloud (Pe-

trenko et al., 2020).

Surveying or testing via Google Forms allows not

only to significantly increase the level of research or

testing, to reach a large number of students but also

to reduce the labour costs of data processing for the

teacher. After all, it is achievable to create an un-

limited number of surveys, questionnaires, tests and

invite an endless number of respondents. Tasks may

vary in different spheres of the discipline and include

questions on a specific topic or general topic or even

an entire course. Besides, Google-forms allows you

to create a form with different elements or types of

questions where each can be made mandatory or op-

tional. While creating a form, you may change the or-

der of questions and choose different designs for their

design. The link to the form is generated automati-

cally after its creation.

To better monitor the students’ academic achieve-

ments and, in turn, to join the well-designed learning

goals, the distance learning assessment affords note-

worthy chances during the educational process.

To clarify the dynamics of indicators of psy-

chological safety of the educational environment of

higher education institutions during the year in a re-

survey Google Forms was supplemented with ques-

tions:

1. If you compare your sense of psychological safety

and comfort in an educational institution today

and a year ago?

2. If you compare your attitude to distance education

now and a year ago?

3. If you compare your psychological well-being

(including mental health) now and a year ago?

Respondents had to choose from the following an-

swer options:

a) significantly worsened

b) has worsened

c) practically has not changed

d) has improved

e) significantly improved

Besides, we were interested in aspects related to

the experience of psychological security and well-

being in online learning, in particular:

1. What measures, actions did you take for your own

development during the quarantine period?

2. Are you ready to fully switch to online learning?

The Psychological Safety of the Educational Environment of Ukrainian Higher Education Institutions in a Pandemic: Empirical Data of a

Comparative Analysis of Participants’ Assessments Studying Online

17

The research used the content analysis with the

focus on determining the relationship between psy-

chological safety and well-being of participants in the

educational process, and their knowledge and prac-

tical activities in the context of distance learning.

Yuriy Fedkovych Chernivtsi National University and

SHEI “The University of Educational Management”

respondents were invited to participate in the study,

acquainted with the purpose, scope and process of the

study; received permission from the teaching staff,

who agreed to participate. Information sheets about

the research and a questionnaire in the Google Forms

were sent to the participants of the educational pro-

cess via e-mails. The survey was conducted at the

beginning of the previous year (March, I stage), and

at the end of 2020 (December, II stage) a re-form was

sent to the addresses specified in the generalized Ex-

cel sheet.

Responses came from almost all respondents in

the first sample, who responded positively to the sit-

uation of re-survey. This, in particular, is evidenced

by the instructions in a large number of sent response

forms such as: “I was glad to help”, “Thank you very

much for your interest in our psychological state”,

“Thank you for the opportunity to participate in the

survey” etc.

Participants in the educational process received in-

formation from research staff on unclear issues or sit-

uations by e-mail. This way ensured that the partici-

pants in the educational process gave clear answers to

the questions asked.

Statistical data processing and graphical presenta-

tion of results was carried out using the SPSS 17.0.

4 ANALYSIS OF THE RESEARCH

RESULTS

4.1 Social and Demographic

Characteristics of the Research

Sample

The main group of respondents consisted of 174 peo-

ple – representatives of socionomic professions of

Yuriy Fedkovych Chernivtsi National University and

SHEI “The University of Educational Management”,

whose professional activities include “spiritual and

moral maturity”, “increased moral responsibility” and

“values to people’s lives”, “willingness to face chang-

ing challenges” and “uncertainty” (Taormina and Sun,

2015). The respondents were divided into groups ac-

cording to:

• gender (37.9% male & 62.1% female);

• age (up to 20 years – 15.5%, 20-30 years – 41.4%,

30-40 years – 15.5%, 40-50 years – 15.5%, over

50 years – 12.1%);

• place of residence (village – 41.4%, town –

58.6%);

• status (student – 75.9%, teacher – 24.1%) (ta-

ble 1).

The separation of groups depending on the sex of

the respondents was due to the gender features of the

perception of psychological safety of the environment

in different spheres of public life revealed in the re-

search (Callahan, 2004). In particular, gender dissim-

ilarity may have a more negative impact on the psy-

chological safety of men with an increased number of

women in working groups than on the psychological

safety of women with an increased number of men in

workgroups (Tsui et al., 1992). Accordingly, gender

types contrasted by birth, so we determined the gen-

der stereotypes by positive or negative prejudgments

(Skitka and Maslach, 1990; Petrenko et al., 2020). We

believed that psychological safety allows you to fully

engage in work responsibilities without fear of neg-

ative consequences for your status, career or image

(Kahn, 1990).

We also considered the age of the educational pro-

cess participants in the context of their perception of

the environment psychological safety. Hence, accord-

ing to the researchers (Safety FOCUS, 2019), there is

a different perception of various aspects of psycholog-

ical safety of different generations and, equally, age

groups.

Based on the results of our study, we revealed dif-

ferences in the psychological safety of the educational

environment depending on the status of participants in

the educational process (teacher, student). This case

research question was how stable the detected trend is.

Moreover, we have found similar trends in other stud-

ies, such as Nembhard and Edmondson (Nembhard

and Edmondson, 2006) of the psychological safety of

the environment and professional status.

We also determined the peculiarities of assessing

the level of psychological safety by the place of the

respondents. We assumed that there are more risks in

the city to ensure the psychological safety of the edu-

cational environment than in the countryside. The ba-

sis for this assumption was the study (Gilemkhanova,

2019), which dealt with such differences.

Another controlled variable was the basic educa-

tion of respondents (social and humanitarian or nat-

ural and mathematical. In this context, we counted

on both our practical experience and Tsvyetkova

(Tsvyetkova, 2014) study, which indicates a differ-

ence in the value and meaning of teachers of differ-

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

18

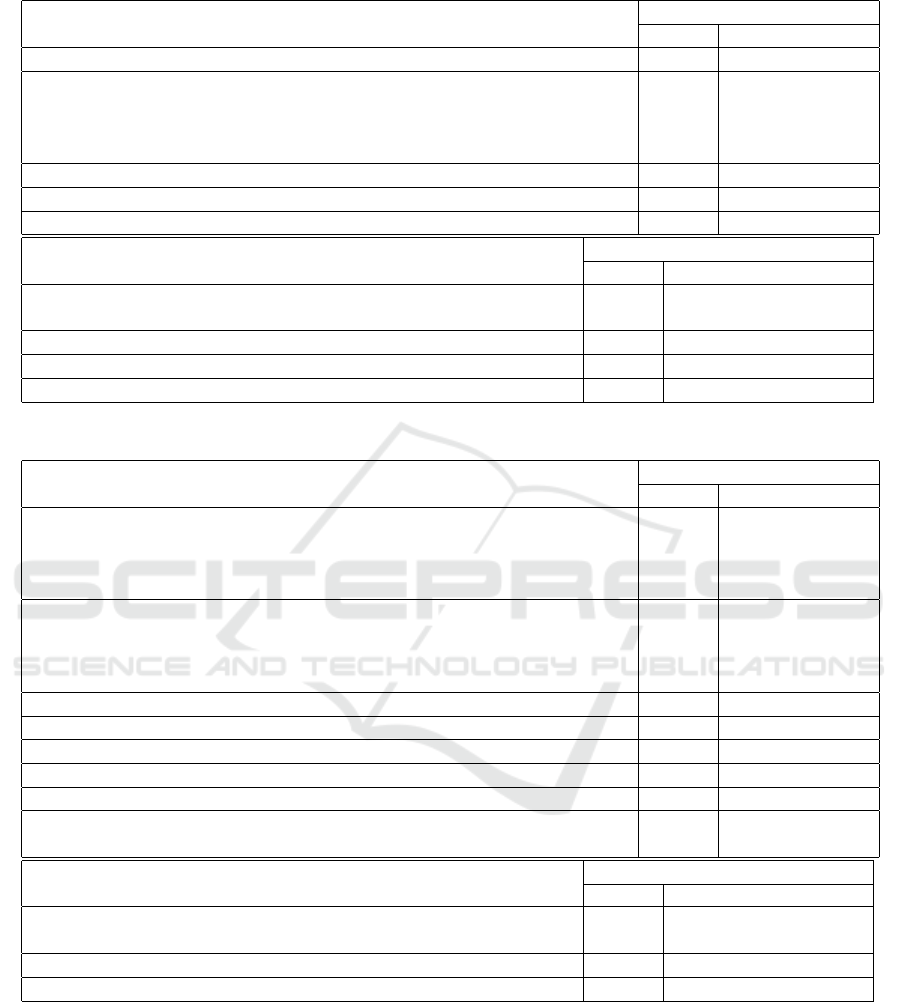

Table 1: Groups of the respondents.

Groups of the respondents Frequency Valid Percent

Gender

female 108 62.1

male 66 37.9

Age

up to 20 years 27 15.5

20-30 years 72 41.4

30-40 years 27 15.5

40-50 years 27 15.5

over 50 years 21 12.1

Place of residence

village 72 41.4

town 102 58.6

Status

student 132 75.9

teacher 42 24.1

Basic education

social and humanitarian 123 72.4

natural and mathematical 47 27.6

ent specialities. The author emphasizes that teach-

ers of socio-humanitarian profile have conformist val-

ues (education, self-control), and more dependent on

socio-political ideology; teachers of natural sciences

and mathematics are based on individualistic values

(independence, boldness, rationalism), independence

of thinking from political events, focus on rigidly

fixed laws, patterns, principles (Tsvyetkova, 2014).

Based on these considerations, the following re-

search hypotheses were formulated.

H

1

: The psychological safety of the educational

environment of the higher education institution and,

as a result, the subjective well-being of the partici-

pants in the educational process in a pandemic have

deteriorated.

H

2

Participants in the educational process are dif-

ferent: gender (H

3−1

), age (H3 − 2), place of resi-

dence (H

3−3

), status (H

3−4

), basic education (H

3−5

)

differ in the levels of experience of psychological

safety of the educational environment.

H

3

: The number of respondents with a positive

attitude towards distance learning and a willingness

to work exclusively online has decreased.

4.2 Dynamics of Indicators of

Psychological Safety of the

Educational Environment for

Participants and Their Subjective

Well-being of the Educational

Process Online

Under the condition of psychological safety, a person

perceives the world around him/her as emotionally

safe or free from emotional pressure (Taormina and

Sun, 2015, pp. 173-188). People who feel psycholog-

ically protected do not perceive the world and other

people as a threat. A sense of psychological safety

creates a pleasant interpersonal relationship and al-

lows you to take risks to achieve high life goals (Afo-

labi and Balogun, 2017, pp. 247-261).

Quarantine causes a crisis for society, and, in par-

ticular, education. It is well-known that during the

crisis it is difficult for people (as well as for educa-

tional institutions) to fully realize their expectations

and competencies. The experience of distance edu-

cation in higher education institutions shows that the

level of these competencies is very different. Hence,

we, as a society, who strive for better higher edu-

cation, have to invest wisely, strengthen universities,

promote creative ideas and find resources for their im-

plementation. It is a key prerequisite for their qualita-

tive transformation.

The effectiveness of a modern educational insti-

tution is measured not only by the quality of educa-

The Psychological Safety of the Educational Environment of Ukrainian Higher Education Institutions in a Pandemic: Empirical Data of a

Comparative Analysis of Participants’ Assessments Studying Online

19

tion but also by students’ safety and teachers’ safety.

According to the results, this study in I

st

stage indi-

cated the low and the average levels of psychological

safety of the educational environment, i.e. in 40.1%

of socionomic professions (10.3% and 25.9%, respec-

tively), 63.8% of the respondents showed the high and

very high levels (table 2).

Table 2: Levels of psychological safety.

Levels of safety I stage, % II stage, %

low 10.3 11.8

average 25.9 33.5

high 50.0 39.4

very high 13.8 15.3

The obtained results determine the nature of the

interaction, communication of the respondents of the

educational process, the possibility of meeting and

developing the needs of the individual in a sense of

safety, maintaining and improving self-esteem, recog-

nition, the formation of a positive self-concept, self-

actualization, etc.

Instead, the second stage of the study (at the end

of last year) deals with the relative deterioration of

psychological safety indicators for participants in the

educational process: a decrease in the number of par-

ticipants who rated psychological safety as high from

50% to 39.4% and an increase in the number of par-

ticipants who rated safety as average (from 25.9% to

33.5%) and low (from 10.3% to 11.8%). At the same

time, the share of respondents who noted the level of

psychological safety of the educational environment

as very high (from 13.8% to 15.3%) (differences at

the level of a weak trend, p = 0.14) increased slightly.

The obtained results are consistent with the partic-

ipants’ assessment of the level of psychological safety

of the educational environment compared to a year

ago (table 3). Respondents were asked to determine

whether the psychological safety of the educational

environment had changed for them during the year.

Table 3 shows that less than half of the respon-

dents (42.9%) note that the level of psychological

safety has not changed.

One-third of respondents (29.4%) indicate an im-

provement, and 6.5% – a significant improvement in

the level of psychological safety. Instead, every fifth

participant in the survey indicates a decrease in the

level of psychological safety – deterioration (12.4%)

or significant deterioration (8.8%). There have been

changes in the subjective well-being of participants in

the educational process in a pandemic, as evidenced

by their answers to the question “If you compare your

psychological well-being (including mental health)

now and a year ago. . . ” (table 4).

As in the previous case, only less than half of the

participants (47.1%) indicate that their psychological

well-being (including mental health) has practically

not changed. 16.5% of respondents indicate an im-

provement, and 2.4% – a significant improvement in

their well-being.

On the other hand, one-third of the participants in

the educational process noted that their psychologi-

cal well-being (including mental health) deteriorated

during the year (21.2%) or significantly deteriorated

(12.9%). The Spearmen rank correlation coefficient

revealed a direct, statistically significant correlation

between the dynamics of changes in the psychologi-

cal safety of the educational environment and the sub-

jective well-being of participants in the educational

process.

We established that the deterioration of psycho-

logical safety of the educational environment is ac-

companied by a decrease in the level of subjective

well-being of respondents, which is a confirmation

(as in previous studies (Bondarchuk, 2018b; Baeva,

2020)) of the relationship of these phenomena. Thus,

the results indicate a partial confirmation of hypothe-

sis H

1

that the psychological safety of the educational

environment of higher education institutions and, as a

consequence, the subjective well-being of participants

in the educational process in a pandemic has deterio-

rated.

4.3 Socio-demographic and

Organizational-professional

Peculiarities of Psychological Safety

of the Educational Environment for

Participants of the Educational

Process Online

By the purpose and objectives of our study, the truth

of hypothesis H

2

about the differences in the lev-

els of experience of psychological safety of the ed-

ucational environment by participants in the educa-

tional process depending on their socio-demographic

(gender, age, place of residence), and organizational-

professional (status, basic education) characteristics

was tested.

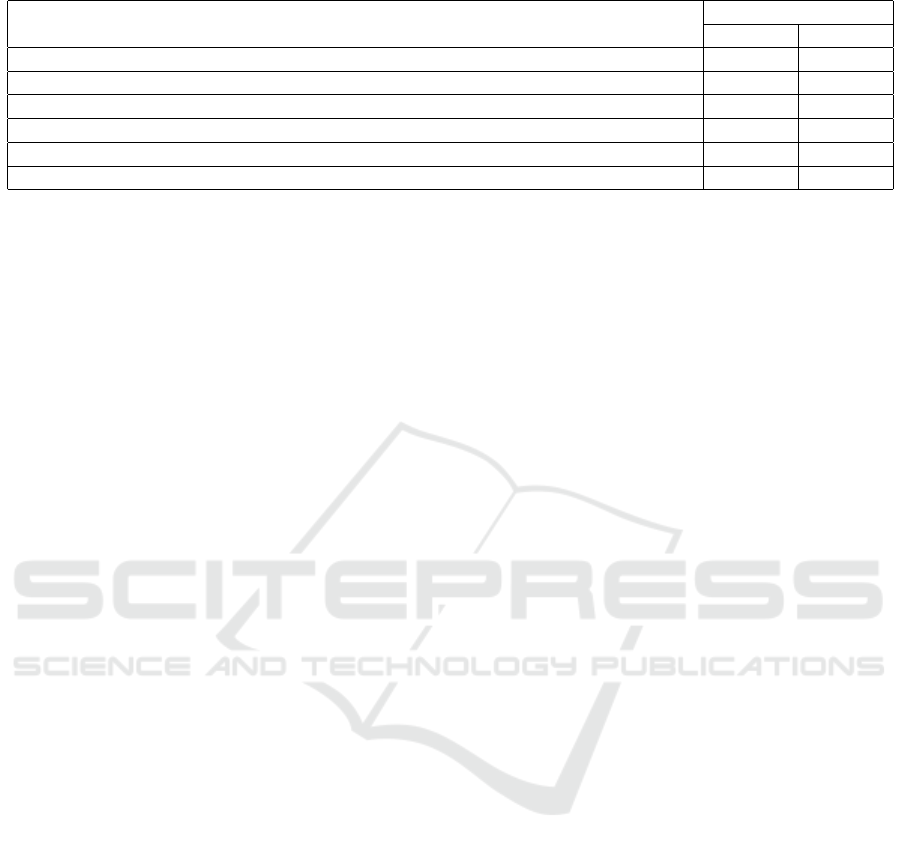

According to the results of ANOVA, the research

revealed statistically significant differences in the pe-

culiarities of psychological safety of the educational

environment of participants in the educational process

depending on gender and professional status (figure 1,

p < 0.01).

Figure 1 shows that male feel more psychologi-

cally protected than women, and students feel more

psychologically protected than teachers. Similar de-

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

20

Table 3: Levels of the psychological safety in the educational institution today and a year ago.

Levels of safety today compared to a year ago Percent

significantly worsened 8.8

worsened 12.4

practically has not changed 42.9

improved 29.4

significantly improved 6.5

Table 4: Levels of the psychological well-being (including mental health) today and a year ago.

Levels of the psychological well-being compared to a year ago Percent

significantly worsened 12.9

worsened 21.2

practically has not changed 47.1

improved 16.5

significantly improved 2.4

We established that the deterioration of psychological safety of the educational environment is accompanied by a

decrease in the level of subjective well-being of respondents, which is a confirmation (as in previous studies [3; 14]) of

the relationship of these phenomena. Thus, the results indicate a partial confirmation of hypothesis H

1

that the

psychological safety of the educational environment of higher education institutions and, as a consequence, the

subjective well-being of participants in the educational process in a pandemic has deteriorated.

1.3 Socio-demographic and organizational-professional peculiarities of psychological safety of

the educational environment for participants of the educational process online

By the purpose and objectives of our study, the truth of hypothesis H

2

about the differences in the levels of

experience of psychological safety of the educational environment by participants in the educational process depending

on their socio-demographic (gender, age, place of residence), and organizational-professional (status, basic education)

characteristics was tested.

According to the results of ANOVA, the research revealed statistically significant differences in the peculiarities of

psychological safety of the educational environment of participants in the educational process depending on gender and

professional status. (Fig. 1. р < 0.01).

Figure 1. The peculiarities of psychological safety of the educational environment of participants

in the educational process depending on gender and professional status

Fig. 1 shows that male feel more psychologically protected than women, and students feel more psychologically

protected than teachers. Similar dependencies were confirmed at repeated research, at the end of the year. This situation,

in our opinion, reflects, on the one hand, the positive trends in the implementation of the student-centred approach, and

on the other hand, the negative trends associated with the ambivalent position of the teacher in modern Ukrainian

society.

At the same time, the picture of experiencing psychological well-being at the end of the year turned out to be

somewhat different.

Table 5. Levels of the psychological well-being (including mental health)

of students and teachers today and a year ago

Levels of the psychological well-being compared to a year ago

Percent

students

teachers

significantly worsened

15,0*

5.4*

worsened

20.3*

24.3*

practically has not changed

50.4*

35.1*

improved

12.0*

32.4*

Figure 1: The peculiarities of psychological safety of the

educational environment of participants in the educational

process depending on gender and professional status.

pendencies were confirmed at repeated research, at

the end of the year. This situation, in our opin-

ion, reflects, on the one hand, the positive trends in

the implementation of the student-centred approach,

and on the other hand, the negative trends associated

with the ambivalent position of the teacher in modern

Ukrainian society.

At the same time, the picture of experiencing psy-

chological well-being at the end of the year turned out

to be somewhat different.

From the data given in table 5, it follows that

the number of students for whom well-being has

significantly deteriorated is higher than for teachers

(15.0% and 5.4%, respectively). On the other hand,

those students for whom the level of psychological

well-being has improved are significantly less than

teachers (12.0% and 32.4%, respectively) (statisti-

cally significant differences were found by criterion

χ

2

, p<0.05).

We attribute these results to the pandemic situa-

tion – a reasonably large number of respondents be-

came ill with COVID-19 (fortunately, there were no

fatalities among them), so it had a negative impact on

their mental state. Based on our experience of inter-

acting with such students, some of them even refused

to turn on their video cameras in class, citing poor

appearance and the fact that they have not yet fully

recovered from the disease.

For many of them, the state of the disease came

as a shock: after all, the media constantly spread in-

formation about the risk of the disease, especially for

the elderly and, mainly, the retired ones, respectively,

they did not perceive the situation as threatening to

themselves. This situation, in our view, raises the is-

sue of the adequacy of media coverage in general and

in a pandemic in particular.

It is noteworthy that at the level of secondary edu-

cation of Russian secondary school pupils and teach-

ers revealed a different trend: teachers of secondary

education found a higher level of psychological safety

than students (Baeva and Bordovskaia, 2015). The

latter, according to researchers may indicate that the

psychological safety of the educational environment

for the teachers and the students can be determined

by various factors (Baeva, 2020, p. 94).

Also, the age-related characteristics of the expe-

rience of psychological safety by participants in the

educational process were confirmed and even became

more pronounced. At the first stage, at the beginning

of the year.

Furthermore, according to the age of participants

in the educational process, 2 categories of respon-

dents feel more protected. Firstly, it is young peo-

ple (up to 20 years old) – mostly students, which in-

dicates, in our opinion, the gradual implementation

of the student-centred approach in higher education.

Secondly, senior responds over the age of 50 (mostly

teachers who have acquired professional status, have

The Psychological Safety of the Educational Environment of Ukrainian Higher Education Institutions in a Pandemic: Empirical Data of a

Comparative Analysis of Participants’ Assessments Studying Online

21

Table 5: Levels of the psychological well-being (including mental health) of students and teachers today and a year ago,

p <0.05.

Levels of the psychological well-being compared to a year ago

Percent

students teachers

significantly worsened 15.0* 5.4*

worsened 20.3* 24.3*

practically has not changed 50.4* 35.1*

improved 12.0* 32.4*

significantly improved 2.3* 2.7*

degrees and titles) and are well established in their ed-

ucational institution (differences in the level of trends,

p = 0.103).

The second phase of the study at the end of the

year draws attention to a certain decrease (compared

to previous data) in levels of psychological safety

for young people (up to 20 years old) and senior re-

sponses over the age of 50 with the general preser-

vation and strengthening of the previously identified

trend. (figure 2, p<0.01).

significantly improved

2.3*

2.7*

* – p < 0.05

From the data given in table 5, it follows that the number of students for whom well-being has significantly

deteriorated is higher than for teachers (15.0% and 5.4%, respectively). On the other hand, those students for whom the

level of psychological well-being has improved are significantly less than teachers (12.0% and 32.4%, respectively)

(statistically significant differences were found by criterion

2

, p < 0.05).

We attribute these results to the pandemic situation - a reasonably large number of respondents became ill with

COVID-19 (fortunately, there were no fatalities among them), so it had a negative impact on their mental state. Based

on our experience of interacting with such students, some of them even refused to turn on their video cameras in class,

citing poor appearance and the fact that they have not yet fully recovered from the disease.

For many of them, the state of the disease came as a shock: after all, the media constantly spread information about

the risk of the disease, especially for the elderly and, mainly, the retired ones, respectively, they did not perceive the

situation as threatening to themselves. This situation, in our view, raises the issue of the adequacy of media coverage in

general and in a pandemic in particular.

It is noteworthy that at the level of secondary education of Russian secondary school pupils and teachers revealed a

different trend: teachers of secondary education found a higher level of psychological safety than students [49]. The

latter, according to researchers may indicate that the psychological safety of the educational environment for the

teachers and the students can be determined by various factors [14, 94].

Also, the age-related characteristics of the experience of psychological safety by participants in the educational

process were confirmed and even became more pronounced. At the first stage, at the beginning of the year.

Furthermore, according to the age of participants in the educational process, 2 categories of respondents feel more

protected. Firstly, it is young people (up to 20 years old) – mostly students, which indicates, in our opinion, the gradual

implementation of the student-centred approach in higher education. Secondly, senior responds over the age of 50

(mostly teachers who have acquired professional status, have degrees and titles) and are well established in their

educational institution (differences in the level of trends, р = 0,103).

The second phase of the study at the end of the year draws attention to a certain decrease (compared to previous

data) in levels of psychological safety for young people (up to 20 years old) and senior responses over the age of 50

with the general preservation and strengthening of the previously identified trend. (Fig. 2. р < 0.01).

Figure 2. The peculiarities of psychological safety of the educational environment of participants

in the educational process depending on age and professional status

Figure 2: The peculiarities of psychological safety of the

educational environment of participants in the educational

process depending on age and professional status.

Furthermore, according to the results of ANOVA,

the results showed the peculiarities of the experi-

ence of psychological safety by participants in the

educational environment depending on their place of

residence (figure 3, at the level of a weak trend,

p = 0.17). Figure 3 shows lower indicators of psy-

chological safety for participants in the educational

process living in the city. This situation is especially

noticeable in students. We clarify this state of affairs

precisely by the specifics of the place of residence

and, in particular, by the artificial restriction of a sig-

nificant number of contacts to which those who live

in the city are accustomed.

For participants from villages, this situation is less

emotional due to fewer direct contacts for villagers. In

the rural type of life, a certain rhythm of life is stricter;

Furthermore, аccording to the results of ANOVA, the results showed the peculiarities of the experience of

psychological safety by participants in the educational environment depending on their place of residence (Fig. 3, at the

level of a weak trend, р = 0.17). Figure 3 shows lower indicators of psychological safety for participants in the

educational process living in the city. This situation is especially noticeable in students. We clarify this state of affairs

precisely by the specifics of the place of residence and, in particular, by the artificial restriction of a significant number

of contacts to which those who live in the city are accustomed.

Figure 3. The peculiarities of psychological safety of the educational environment of participants

in the educational process depending on age and professional status

For participants from villages, this situation is less emotional due to fewer direct contacts for villagers. In the rural

type of life, a certain rhythm of life is stricter; there is less choice of occupations, a narrowed space of communication.

Our assumption about features of psychological safety of educational environment for participants of educational

process with various education was confirmed (Fig. 4, at the level of weak tendency, р = 0.16).

Figure 4 displays that in the case of the social and humanitarian orientation of the participants in the educational

process, the psychological safety of the educational environment is perceived higher than for representatives of natural

and mathematical education.

The obtained results are consistent with the data of E. N. Gilemkhanova [46] according to which, there is an

impressively higher level of the rigour of the risk of socio-psychological safety in the educational environment in cities

and towns than in the village. The researcher notes that the contextual factors have lower links with the socio-

psychological safety index, as contrasted with other personal points. The practical value of this study is that this

information helps to objectively assess the risks of social and psychological safety in a particular educational

environment. It is also necessary to take timely preventive measures in the most stressful institutions in terms of

psychological safety. Increasing psychological prevention work with students with different risk indicators is more

relevant [45, 9].

A detailed analysis of the results revealed both the most problematic and relatively favourable areas of

psychological safety for participants in the educational process, which are somewhat different for teachers and students

(Tables 6, 7).

Thus, according to the results of the first stage students feel protected in the following aspects of their educational

activities: continuous improvement of professional skills (54%), development of abilities (54%), the opportunity to

express their points of view (48%), ask for help (46.8%).

Figure 3: The peculiarities of psychological safety of the

educational environment of participants in the educational

process depending on age and professional status.

there is less choice of occupations, a narrowed space

of communication.

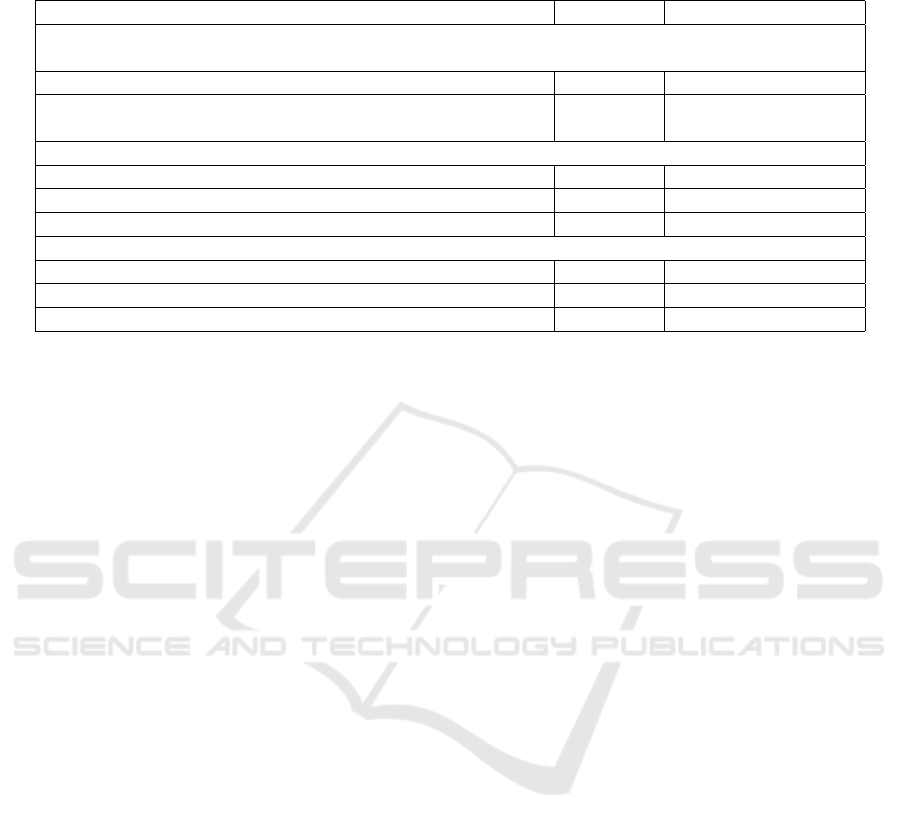

Our assumption about features of psychological

safety of educational environment for participants

of educational process with various education was

confirmed (figure 4, at the level of weak tendency,

p = 0.16).

Figure 4. The peculiarities of psychological safety of the educational environment of participants

in the educational process depending on base education and professional status

According to the second section, the picture has changed somewhat: the students’ positive assessment of what has

increased work in a higher education institution requires constant improvement of professional skills (73.7%).

Instead, the benefits of the educational environment in terms of interpersonal relationships have diminished

significantly. Thus, according to students, the opportunity to express their point of view has significantly decreased

(24.8%). It also became smaller the opportunity to ask for help (39.8%).(Table 6).

Table 6. Some questions about the psychological safety of the high education students*

Problem areas of psychological safety

the low level of

safety %

Relatively favourable areas of

psychological safety

the very high

level of safety, %

I stage

II stage

I stage

II stage

The mood at your work that you do

21.5

21.1

Working in your educational

institution requires constant

improvement of professional skills

54.0

73.7

Protection from public humiliation:

by students

by teachers

by the administration

19.9

22.3

23.8

8.3

6.2

11.3

The work you have to do helps to

develop your abilities

54.0

50.4

Protection from being ignored by the

administration

16.6

9.8

The opportunity to express your point

of view

48.0

24.8

Protection from threats from the

administration

11.9

7.5

Opportunity to ask for help

46.8

39.8

Protection from unfriendly attitude of

students

1.5

8.3

Instead, according to the results of the first stage students feel psychologically unprotected because of the negative

mood at work they do (21.5%); public humiliation: by students (19.9%), teachers (22.3%), administration (23.8%), being

ignored by the administration (16.6%) and threats from the administration (11.9%).

At the end of the year, the situation in this context somewhat eased, but new threats to the psychological safety of

the educational environment appeared, in particular, protection from an unfriendly attitude of students decreased, the

low level of which was found in 8.3% of students compared to 1.5% at the beginning of the research. (Table 6).

Similar dynamics of views on various aspects of psychological safety of the educational environment is found in

teachers. Thus, the results of the first stage teachers feel more psychologically safe in the constant improvement of

natural and mathematical educationsocial and humanitarian education

education

108

107

106

105

104

103

Estimated Marginal Means

Estimated Marginal Means of psychological safety

Figure 4: The peculiarities of psychological safety of the

educational environment of participants in the educational

process depending on base education and professional sta-

tus.

Figure 4 displays that in the case of the social and

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

22

humanitarian orientation of the participants in the ed-

ucational process, the psychological safety of the edu-

cational environment is perceived higher than for rep-

resentatives of natural and mathematical education.

The obtained results are consistent with the data

of Gilemkhanova (Gilemkhanova, 2019) according to

which, there is an impressively higher level of the

rigour of the risk of socio-psychological safety in the

educational environment in cities and towns than in

the village. The researcher notes that the contextual

factors have lower links with the socio-psychological

safety index, as contrasted with other personal points.

The practical value of this study is that this informa-

tion helps to objectively assess the risks of social and

psychological safety in a particular educational envi-

ronment. It is also necessary to take timely preventive

measures in the most stressful institutions in terms of

psychological safety. Increasing psychological pre-

vention work with students with different risk indi-

cators is more relevant (Nembhard and Edmondson,

2006; Hinduja and Patchin, 2010).

A detailed analysis of the results revealed both

the most problematic and relatively favourable areas

of psychological safety for participants in the edu-

cational process, which are somewhat different for

teachers and students (tables 6, 7).

Thus, according to the results of the first stage

students feel protected in the following aspects of

their educational activities: continuous improvement

of professional skills (54%), development of abilities

(54%), the opportunity to express their points of view

(48%), ask for help (46.8%).

According to the second section, the picture has

changed somewhat: the students’ positive assessment

of what has increased work in a higher education

institution requires constant improvement of profes-

sional skills (73.7%).

Instead, the benefits of the educational environ-

ment in terms of interpersonal relationships have di-

minished significantly. Thus, according to students,

the opportunity to express their point of view has sig-

nificantly decreased (24.8%). It also became smaller

the opportunity to ask for help (39.8%) (table 6).

Instead, according to the results of the first stage

students feel psychologically unprotected because of

the negative mood at work they do (21.5%); public

humiliation: by students (19.9%), teachers (22.3%),

administration (23.8%), being ignored by the admin-

istration (16.6%) and threats from the administration

(11.9%).

At the end of the year, the situation in this context

somewhat eased, but new threats to the psychologi-

cal safety of the educational environment appeared,

in particular, protection from an unfriendly attitude of

students decreased, the low level of which was found

in 8.3% of students compared to 1.5% at the begin-

ning of the research (table 6).

Similar dynamics of views on various aspects of

psychological safety of the educational environment

is found in teachers. Thus, the results of the first

stage teachers feel more psychologically safe in the

constant improvement of professional skills (45.8%),

the development of their abilities in the process of

work (33.3%), and getting pleasure from their activi-

ties (41.7%).

Instead, according to the second section, the pic-

ture has changed: teachers’ positive assessment that

the work in a higher education institution requires

constant improvement of professional skills has in-

creased significantly (from 45.8% to 97.3%), also,

that the development of their abilities in the process

of work (from 33.3% to 83.8%). In our opinion, this

is explained by the need to master new digital tech-

nologies to perform their duties well in the conditions

of mass transition to distance learning. Instead, the

mood in a teachers ‘work that they do worsen (from

41.7% to 35.1%) (table 7).

However, according to the results of the first stage

they are psychologically unprotected from public hu-

miliation as a devaluation of the teacher’s profes-

sional achievements, groundless criticism in the pres-

ence of others, especially by colleagues (39.8%), ad-

ministration (27.3%); threats from students (31.3%),

colleagues (43.8%), administration (25%). Besides,

there are problems with the manifestation of initia-

tive activity (37.5%), expressing their point of view

(25%), receiving some help (25%), taking into ac-

count their problems and difficulties in professional

activities (25%).

At the end of the year, these threats to teach-

ers mostly decreased, in particular, they were psy-

chologically unprotected from public humiliation,

especially by colleagues (32.4%), administration

(10.8%); threats from colleagues (37.8%), adminis-

tration (21.6%). Besides, there are problems with the

manifestation of initiative activity (8.1%), express-

ing their point of view (5.4%), receiving some help

10.8%). Besides, there is an increase in experience

psychologically unprotected from public humiliation

by students from 24.9% to 35.1%.

At the same time, there are trends for new chal-

lenges in the context of the psychological safety of

the educational environment: the threat that the ad-

ministration will force teachers to do anything against

them will increase from 1.5% to 13.5%. A possi-

ble explanation for the established results may be a

much smaller number of direct contacts of teachers

with colleagues, on the one hand, and a decrease in

The Psychological Safety of the Educational Environment of Ukrainian Higher Education Institutions in a Pandemic: Empirical Data of a

Comparative Analysis of Participants’ Assessments Studying Online

23

Table 6: Some questions about the psychological safety of the high education students.

Problem areas of psychological safety

The low level of safety, %

I stage II stage

The mood at your work that you do 21.5 21.1

Protection from public humiliation:

by students 19.9 8.3

by teachers 22.3 6.2

by the administration 23.8 11.3

Protection from being ignored by the administration 16.6 9.8

Protection from threats from the administration 11.9 7.5

Protection from unfriendly attitude of students 1.5 8.3

Relatively favourable areas of psychological safety

The very high level of safety, %

I stage II stage

Working in your educational institution requires constant improve-

ment of professional skills

54.0 73.7

The work you have to do helps to develop your abilities 54.0 50.4

The opportunity to express your point of view 48.0 24.8

Opportunity to ask for help 46.8 39.8

Table 7: Some questions about the psychological safety of the high education teachers.

Problem areas of psychological safety

The low level of safety, %

I stage II stage

Protection from public humiliation:

by students 24.9 35.1

colleagues 39.8 32.4

by the administration 27.3 10.8

Protection from threats from

by students 31.3 37.8

by teachers 43.8 37.8

by the administration 25.0 21.6

Relationships with colleagues 37.5 8.1

The opportunity to express your point of view 25.0 5.4

Opportunity to show initiative, activity 37.5 8.1

Opportunity to ask for help 25.0 8.1

Taking into account personal problems and difficulties 25.0 10.8

Protection from the fact that the administration will force you to do any-

thing against your will

2.7 13.5

Relatively favourable areas of psychological safety

The very high level of safety, %

I stage II stage

Working in your educational institution requires constant improve-

ment of professional skills

45.8 97.3

The work you have to do helps to develop your abilities 33.3 83.8

The mood in your work that you do 41.7 35.1

the possibility of direct influence on students, on the

other. In the latter case, the student may be formally

present at the lesson, but for various reasons “hide”

behind the author, which accordingly complicates the

ability to control the quality of his inclusion in the

lesson (table 7).

From the data of table 7, it follows that for teach-

ers of higher education it is possible to state an imbal-

ance between relatively favourable and problematic

areas of psychological safety of the educational envi-

ronment towards the latter.

Besides, the problem of compensation for those

socio-psychological mechanisms of influence on the

educational activity of students, which were involved

in the educational process in full-time form and, ac-

cordingly, direct interpersonal communication.

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

24

In general, it is stated that the hypothesis that the

participants in the educational process are different:

gender (H

3−1

), age (H

3−2

), place of residence (H

3−3

),

status (H

3−4

), basic education (H

3−5

) – differ in the

levels of experience of psychological safety of the ed-

ucational environment as a whole confirmed.

The received information on social-demographic

and organizational-professional features of psycho-

logical safety of participants of the educational envi-

ronment it is expedient to consider at the organization

of their psychological support and support in the con-

ditions of training online.

4.4 Survey of Participants in the

Educational Process on Their

Attitude to the Peculiarities of

Learning under the Conditions of

the COVID-19 Pandemic

Thus, to study the peculiarities of learning and the at-

titude of participants to it, we sought to learn about

the sources, online resources where participants in the

educational process obtain information.

Accordingly, the respondents – representatives of

socionomic professions use the Internet search en-

gines, specialized resources, sites, archives, databases

via the Internet (13.3%), social networks (Viber

(16.7%), Facebook (13.3), Instagram (6.7%), Tele-

gram (9.9%), Skype (13.3%), and media (27.8%) to

obtain information. It is clear that, as the distin-

guished reviewer noted, Internet is used in order to

search for information using search engines, special-

ized resources, sites, archives, databases via the In-

ternet. But we were interested in the psychological

aspect of the fact of using the Internet, in general. We

understood psychological humiliation as public hu-

miliation by colleagues and administration as a de-

valuation of the teacher’s professional achievements,

groundless criticism in the presence of others. In fur-

ther editing, if necessary, we can further detail the

content of the psychological safety indicators.

Participants in the educational process use e-

books (27.8%), gadgets (33.4%), and personal com-

puters (16.7%), laptops (22.1%). A small part of the

respondents uses various means (16.7%).

The educational process manages mainly through

such online services as Zoom (33.4%), Google Meet

(16.7%), BigBluButton (3.3%), Moodle (13.3%) and

Google applications (23.3%), which allows organiz-

ing conferences and webinars for different numbers

of users and speakers.

At the end of the year according to the survey the

respondents – representatives of socionomic profes-

sions use the Internet (33.3%), social networks (Viber

(9.7%), Facebook 14.3), Instagram (16.7%), Tele-

gram (19.9%), Skype (2.3%), and media (3.8%) to

obtain information.

Participants in the educational process use e-

books, NAES repository (14.4%), videos recom-

mended by the Ministry of Education and Science

(13.4%), gadgets (23.4%), and personal computers

(26.7%), laptops 25.1%). A small part of the respon-

dents uses various means (13.7%).

The educational process manages mainly through

such online services as Zoom (33.4%), Google

Meet (16.7%), BigBluButton (3.3%), Google

Class (22.2%), Moodle (13.3%), Google Jamboard

(11.1%), and Google applications (53.3%), which

allows organizing conferences and webinars for

different numbers of users and speakers.

Thus, during the quarantine period, teachers and

students are forced to use Internet resources. Qual-

ity online classes require the teacher to improve per-

sonal skills in working with online sources and plat-

forms, as well as to master new information resources

(Asana, Google Docs, Wiki, Dropbox, Google Jam-

board, Kahoot, Miro board, Dashboard, Mentimeter

etc.).

Besides, to positively influence the level of student

achievement in the conditions of distance learning, it

is necessary to create a wide variety of test tasks. Af-

ter all, in contrast to the classroom conditions during

practical classes, the student online may: prepare for

as much time as he needs; pass about a hundred tests

of one topic, which cover all its aspects and allow

him/her to consolidate the lecture material; get a good

knowledge of a particular topic; and, accordingly, to

higher performance.

We also studied what new opportunities in the

context of learning were noted by the participants of

the educational process during the quarantine period.

At the same time, according to criterion χ

2

statisti-

cally significant differences in the choice of classes of

students and teachers were stated (table 8, p < 0.05).

Table 8 shows that teachers, in general, were more

active than students in choosing constructive forms of

activity during quarantine and forced isolation. Ac-

cordingly, while engaging the process of education

during the quarantine period, teachers have higher ac-

tivities in mastering the online course (40.5%) and

passing internship (13.5%) and reading a lot (16.2%)

than students (23.3%, 6.8% and 10.5% respectively).

Thus, students have higher activities in the following

actions: passing advanced training courses (32.3%),

increasing the amount of communication on social

networks (11.3%) and doing nothing but current af-

fairs (15.8) than teachers (21.6%, 2.7% and 5.4% re-

The Psychological Safety of the Educational Environment of Ukrainian Higher Education Institutions in a Pandemic: Empirical Data of a

Comparative Analysis of Participants’ Assessments Studying Online

25

Table 8: Features of activity of participants of educational process during the quarantine period.

What measures, actions did you take for your own Percent

development during the quarantine period? students teachers

mastered the online course 23.3 40.5

passed internships 6.8 13.5

passed advanced training courses 32.3 21.6

read a lot 10.5 16.2

increased the amount of communication on social networks 11.3 2.7

did nothing but current affairs 15.8 5.4

spectively).

Thus, the most important activity for teaches is to

master the online course, whereas for students – to

pass advanced training courses. Despite this, the less

important for teachers is to increase the amount of

communication on social networks, whereas for stu-

dents – to pass internship.

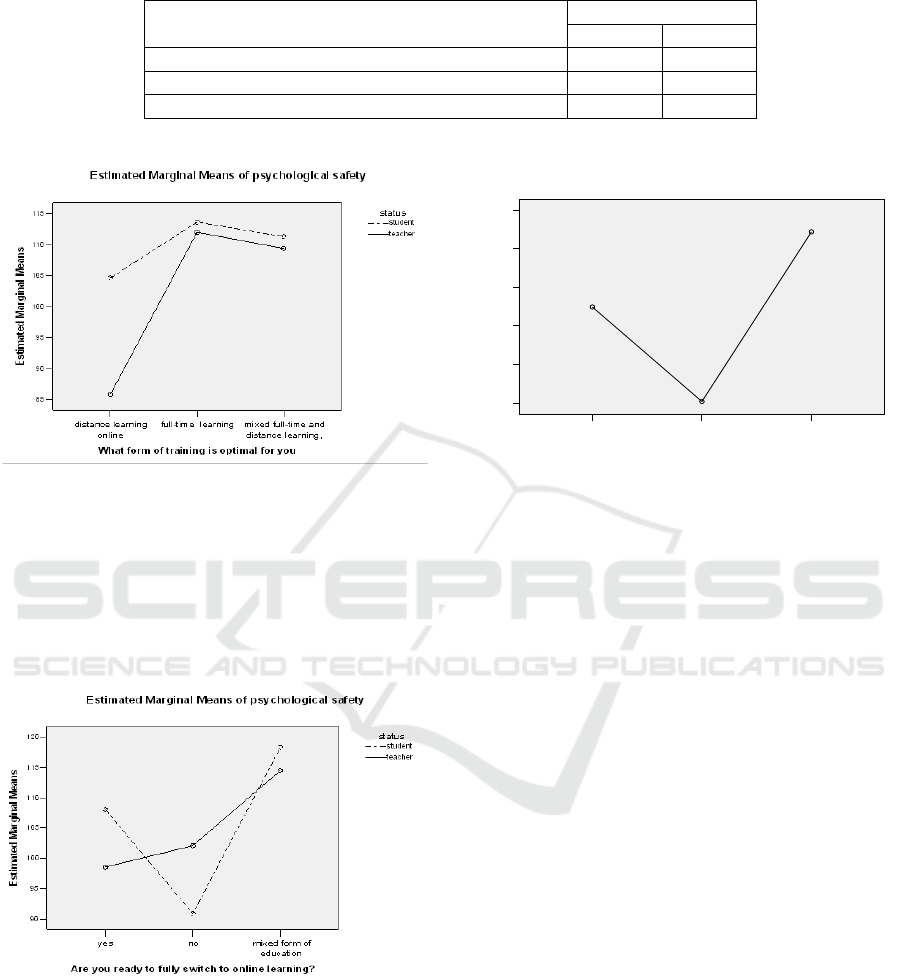

We paid special attention to studying the attitude

of participants in the educational process to the pe-

culiarities of learning in the context of the COVID-19

pandemic. We asked them to answer questions on var-

ious aspects of learning.

Thus, we were interested in how much the edu-

cational institution contributes to the psychological

safety of participants in the educational process. Only

a quarter of respondents believe that the educational

institution partly facilitates (25%). But a third of re-

spondents (27.1%) indicates the opposite, i.e. does

not contribute to the creation of psychological safety

in participants. At the same time, almost half of the

respondents (47.9%) reflect stress caused by quaran-

tine. Importantly, distance learning cannot fully pro-

vide the ability to express emotions, feelings, and the

ability to listen and hear, convince each other, sen-

suality, experience, the formation of moral, spiritual,

and value spheres of the participants. Half of the par-

ticipants in the educational process (52.1%) are sat-

isfied with the form of distance learning. However,

54.2% of people consider mixed full-time and dis-

tance learning to be the optimal form for them (ta-

ble 9).

The results of the study on the educational pro-

cess participants’ attitude to the peculiarities of dis-

tance learning under the COVID-19 conditions are of

interesting. According to the results of the first stage,

the participants mostly feel the psychological safety

from the educational institution under the conditions

of the COVID-19 “partly facilitate” (47.9%), then “on

the contrary, under conditions of quarantine it causes

stress” (27.1%) and “facilitate” (25.0%). However,

the results have changed a bit at the end of the educa-

tional year according to the second stage, i.e. the par-

ticipants of educational process feel more safety psy-

chologically from the educational institution under

the conditions of the COVID-19 “facilitate” (78.4%),

“partly facilitate” (13.5%), and “on the contrary, un-

der conditions of quarantine it causes stress” (8.1%).

Moreover, the results of the table 9 show the state

of being comfortable during distance learning, i.e. of

the first stage the participants of educational process

mostly feel “comfortable” themselves (52.1%) than

“uncomfortable” (37.5%) and “Not quite so, I would

like more F2F communication” (10.4%). Still, the

results of the second stage display the participants

of the educational process have the same attitude to

the state of being “comfortable” and “uncomfortable”

(35.1%). Furthermore, the third section of table 9 due

to the optimal form of training demonstrates chiefly

equal results for the first and second stage, i.e. the

highest state is “mixed full-time and distance learn-

ing” (54.1% and 51.4% respectively), then for the

first stage there is the sequence of preferences: “dis-

tance learning online” (37.5%) and “full-time learn-

ing” (8.3%), but for the second stage there is no se-

quence, just the equal results for both preferences

(24.3% each).

Thus, the results show the appropriate change of

the educational process participants’ attitude to the

peculiarities of distance learning under the COVID-

19 conditions. Hence, there takes place the partici-

pants’ desirability of full-time learning alike distance

learning. Its absence not only causes negative emo-

tions of participants in the educational process but,

also, negatively affects their academic success in the

future (Kuhfeld et al., 2020).

The researchers note that the missing school for a

prolonged period will likely have impacts on student

achievement. Furthermore, students likely are return-

ing this fall with greater variability in their academic

skills.

Taking into consideration the research about stu-

dents, who suffered from Hurricane Katrina (Harris

and Larsen, 2019), it is urgent to make all the com-

fortable conditions without learning loss for the par-

ticipants of the educational process during COVID-

19. Additionally, it is vital to empower educational

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

26

Table 9: The participants’ attitude of the educational process to the peculiarities of distance learning under the COVID-19

conditions.

The participants’ attitude I stage, % II stage, %

Does the educational institution contribute to your psychological safety under the conditions of the

COVID-19?

on the contrary, under conditions of quarantine it causes stress 27.1 8.1

partly facilitate 47.9 13.5

facilitate 25.0 78.4

Is distance learning comfortable for you?

uncomfortable 37.5 35.1

not quite so, I would like more F2F communication 10.4 29.7

comfortable 52.1 35.1

What form of training is optimal for you?

distance learning online 37.5 24.3

full-time learning 8.3 24.3

mixed full-time and distance learning 54.2 51.4

leaders to protect the participants of the educational

process and “researchers to make urgent evidence-

informed post–COVID-19 recovery decisions” (Kuh-

feld et al., 2020, p. 562).

Without a doubt, there are numerous studies and

practical experience of distance learning, which testi-

fies to its advantages. Thus, in recent years, Massive

Open Online Courses (MOOCs) opportunities have

been widely discussed as they are “one of the most

prominent trends in higher education in recent years”

(Baturay, 2015, p. 427). It is a well-known trend for

distance education which gathered all the education

process participants all over the world to share the ed-

ucational content on the online platforms around the

US and Europe, like Coursera, EdX, Udacity, Udemy,

Iversity, MiriadaX, and Futurelearn (Baturay, 2015,

p. 428). These courses are generally formed, set,

and led by academics through open source web plat-

forms (Siemsen et al., 2009; Universities UK, 2013;

Panchenko and Muzyka, 2020).

Moreover, the changes in communication tech-

nologies play a significant role in social life and create

new opportunities in the field of education. Nowa-