Methodology of M. Montessori as the Basis of Early Formation of STEM

Skills of Pupils

Iryna A. Slipukhina

1,2 a

, Arkadiy P. Polishchuk

2 b

, Sergii M. Mieniailov

2 c

,

Oleh P. Opolonets

2 d

and Taras V. Soloviov

2 e

1

National Center “Junior Academy of Sciences of Ukraine”, 38/44 Dehtiarivska Str., Kyiv, 04119, Ukraine

2

National Aviation University, 1 Liubomyra Huzara Ave., Kyiv, 03058, Ukraine

Keywords:

Constructivism in Education, Innovative Pedagogical Technologies, Montessori, STEM, STREAM, STEAM,

Web Mapping.

Abstract:

The ideas of the constructivist paradigm of education continue to develop in the XXI century. In this context,

the STEM approach is being implemented very dynamically for the formation of curricula of formal and non-

formal education institutions. At the same time, M. Montessori pedagogy educational centers remain popular

in Ukraine. Based on the use of web mapping service Google Maps, the authors searched, identified and

quantitatively analyzed the distribution of educational institutions in Ukraine that use the STEM-STEAM-

STREAM approach and methodological tools of M. Montessori pedagogy. The results of data processing are

presented in the form of author’s maps and diagrams, which indicate the number of Montessori pedagogy

centers and STEM-STEAM-STREAM training centers for each region. Based on the data of the official

websites of educational institutions, an analysis of the content and organization of some Montessori centers

in Ukraine was carried out that is demonstrated by means of examples. To obtain a conclusion about the

state of development of pedagogical technologies the method of Gartner Hype Cycle is used. Comparison of

the principles of pedagogy M. Montessori and STEM approach to education reveals many common didactic

features based on the ideas of constructivism in education. In particular, we want to note the features of

active interaction of subjects of the educational process, the development of curiosity, change of the teacher

functions.

1 INTRODUCTION

The requirement of society to form the ability and

readiness of the individual for successful socializa-

tion to withstand the challenges of the XXI century

determines the development of the variable education

in Ukraine, which is demonstrated in the reform of

education at all levels. This is supported by the au-

tonomy of educational institutions (Verkhovna Rada

of Ukraine, 2017) and, as a consequence, the devel-

opment of educational services based on a wide range

of innovative programs and methods. The STEM ap-

proach is gaining popularity in educational environ-

ment (Kramarenko et al., 2020); it is streamlined by

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9253-8021

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6892-5403

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4871-311X

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5059-5298

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4033-0090

the support of the state (IMZO, 2016).

The pedagogical system of M. Montessori (Dy-

chkivska and Ponymanska, 2009) is acknowledged as

a classic innovative technology of education for chil-

dren from the very young age, its relevance is con-

firmed by the functioning of numerous pedagogical

centers. Note that the Montessori approach meets all

the principles of humanitarian pedagogy: the child’s

personality with all individuality, similarity and dif-

ference from other children is in the center of the ed-

ucational process (Mavric, 2020).

On the other hand, the pedagogical problem of

early detection and development of engineering abil-

ities is especially relevant in the era of rapid devel-

opment of tools and technologies. In this context,

significant help is expected from innovative learning

technologies, which include the STEM approach in

education (Krutiy and Hrytsyshyna, 2016; Marshall,

2017).

The development of the educational centers in

Slipukhina, I., Polishchuk, A., Mieniailov, S., Opolonets, O. and Soloviov, T.

Methodology of M. Montessori as the Basis of Early Formation of STEM Skills of Pupils.

DOI: 10.5220/0010922500003364

In Proceedings of the 1st Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology (AET 2020) - Volume 1, pages 211-220

ISBN: 978-989-758-558-6

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

211

Ukraine is result of the society and the state demand.

Is M. Montessori’s pedagogical technology relevant

for domestic educational institutions in comparison

with the STEM-STEAM-STREAM approach? What

unites these different pedagogical systems? Up-to-

date data for the answers can be obtained through the

use of web mapping service tools Google Maps.

2 ANALYSIS OF RECENT

PUBLICATIONS AND

RESEARCH

Almost 120 years of implementation of Montessori

pedagogical ideas around the world are reflected

in numerous scientific works (Smith, 1911; Allen,

1913; Paton, 1915; Levy and Bartelme, 1927; Stern,

1930; Claremont, 1952; Montessori, 1961; Drenck-

hahn, 1961; Beck, 1961; Stendler, 1965; Denny,

1965; Argy, 1965; Roeper, 1966; Denny, 1966; Git-

ter, 1967b,a, 1970; Morra, 1967; Cohen, 1968; Edg-

ington, 1970; Edwards, 2002; Lopata et al., 2005;

Rathunde and Csikszentmihalyi, 2005; Lillard and

Else-Quest, 2006; Lillard, 2012; Lillard et al., 2017;

Dohrmann et al., 2007; Beatty, 2011; Whitesgarver

and Cossentino, 2008; Dodd-Nufrio, 2011). The ideas

also prove the relevance in the XXI century: from

the earliest works on the introduction of Montes-

sori methods as a didactic tool for speech devel-

opment of preschool children and teaching them to

read and write (Dychkivska and Ponymanska, 2009),

through the study of sensory and motor skills, game

techniques to stimulate communicative activity of

preschoolers as a basis of speech skills. The need

for integrative techniques based on the STREAM ap-

proach is revealed in the work of Krutiy and Hryt-

syshyna (Krutiy and Hrytsyshyna, 2016). Mavric

(Mavric, 2020) emphasizes on the importance of ped-

agogical ideas of M. Montessori for educational sys-

tems of the XXI century exploring the didactic as-

pects of personalized instructions; in particular, she

points to the dual role of the teacher as “knowledge

facilitator who offers advice and is a training spe-

cialist” at the same time. The same work shows the

best academic results of the pupils comparatively to

other public or private primary schools, in particu-

lar, in mathematics and physics (Mavric, 2020). Es-

sential for the Montessori teaching method is the dy-

namic interaction of the triad “child, teacher, environ-

ment (prepared situations)”. Remarkable is compre-

hension of the Montessori Method proposed by Mar-

shall (Marshall, 2017) in the context of two impor-

tant aspects: educational materials and the way in

which the teacher and the design of the prepared en-

vironment promote independent interaction of chil-

dren with these materials. It also draws attention

to confirmed over time significant adaptability of the

method.

On the other hand, socio-economic processes and

challenges of the XXI century determine the problem

of high-quality technical and technological teaching

of the younger generation: the STEM abbreviation

is actively used in all spheres of our life to describe

processes in the agro-industrial complex, medicine,

energy, robotics, IT market, transport, industry, and,

above all, in education.

The abbreviation STEAM (Science, Technology,

Engineering, Arts / All, and Mathematics) is widely

used nowadays to indicate that the technology is

used to study not only technical sciences but also

arty disciplines, for example, industrial aesthetics,

industrial design, 3D modeling, architecture, cin-

ema (Stetsenko, 2016). Another important area is

the STREAM approach in education (Science, Tech-

nology, Reading + WRiting, Engineering, Arts and

Mathematics) aimed at early education of the culture

of engineering thinking and the formation of pupils’

skills in technology, science, reading and writing, en-

gineering , art and mathematics. This approach is in-

tended to form critical thinking of preschool and pri-

mary school children; according to the age character-

istics, mainly emotions are used to motivate the chil-

dren to learn (Krutiy and Hrytsyshyna, 2016). In gen-

eral, the key aim of STEM-STEAM-STREAM ap-

proaches to curriculum development is to expand the

consciousness of participants of the educational pro-

cess, help to actively respond to changes in reality but

not “direct transfer” of knowledge (IMZO, 2016).

At the same time, according to Lapon (Lapon,

2020), the methods based on the ideas of M. Montes-

sori are focused on the education of respect for learn-

ing, encouraging the child’s curiosity through realistic

experience, creativity and self-understanding.

In order to determine the probable “points of

contact” of the STEM / STREAM approach and

M. Montessori’s methodology, we will consider their

peculiarities of educational process. According to

the description of Dychkivska and Ponymanska (Dy-

chkivska and Ponymanska, 2009), M. Montessori’s

method is aimed at studying five aspects of life: prac-

tical life skills, sensory, mathematics, speech develop-

ment (reading and writing), space education (history,

time, nature). The child’s independence and free-

dom is at the center. Possibility for pupils to make

mistakes, analyze them, seek help from more expe-

rienced pupils or the teacher. This technique effec-

tively encourages the development of critical thinking

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

212

and forms the skills of finding creative approaches to

problems solving (Lapon, 2020).

A long time of research and practical implemen-

tation of methods based on the ideas of M. Montes-

sori showed that it is most effective at the early stages

of child development. This leads to the assumption

about its similarity with STEM and STREAM ap-

proaches aimed at early career guidance of new gen-

erations, deepening skills, creating opportunities for

research work, conducting scientific and technical ac-

tivities and more.

3 RESEARCH METHODS

The aim of the article is to clarify the roots of com-

mon features of Montessori pedagogy and teaching

methods based on the STEM-STEAM-STREAM ap-

proach. Subsequent aim is a comparison of their ap-

plicability in the educational space of Ukraine based

on data web mapping service Google Maps.

To compare educational technologies in Montes-

sori schools and STEM-STEAM-STREAM educa-

tional centers, the analysis of scientific literature and

data from open sources is used, which demonstrate

the current practical aspects of the implementation of

these methods in Ukraine.

An important indicator of the activity of the use

of the above mentioned innovative learning technolo-

gies is the public demand for running of the related

centers of education. For this purpose, the search and

identification by means of the web mapping service

of the Google Maps system was used. An example

of the result of such a search is shown in figure 1;

it demonstrates a screenshot of the Google Maps ap-

plication for a search inquiry for the keywords “Zhy-

tomyr Montessori School”, “Zhytomyr Montessori

Kindergarten”, “Montessori Zhytomyr”.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

Comparisons of the system of free education of

M. Montessori and STREAM-approach in education

reveal many common features, in particular:

• focus on the formation of certain skills, their con-

junction with knowledge of the world around,

self-awareness and own role in society;

• the possibility of effective implementation of

these technologies at all stages of child develop-

ment;

• joint activities of teacher and pupil aimed at solv-

ing practically significant problems;

• use of acquired skills in everyday life with an ap-

proximation for future professional activity;

• promoting communication and team spirit;

• development of interest to certain actions, sub-

jects, and the process of new knowledge obtain-

ing;

• introduction of creative and innovative ap-

proaches in the educational process;

• preparing the student for future successful so-

cialization and the formation of lifelong learning

skills.

4.1 The Paradigm of Constructivism in

Education as the Basis of Similarity

of Methods

The similarity of these pedagogical technologies, the

implementation of which separates 100 years, should

be evaluated as a practical embodiment of the con-

structivist paradigm of education; its origins are in the

interdisciplinary field of philosophy, psychology, so-

ciology and education (Bada, 2015). Note that the de-

velopment of constructivism as an evolutionary epis-

temology began with the works of von Glasersfeld

(von Glasersfeld, 1995), Piaget (Piaget, 1980), Vy-

gotsky (Vygotsky, 1962) and others. The main idea

of this philosophical trend in the context of learning

and teaching concerns the mutual influence of partici-

pants of the educational process and learning environ-

ment (Komar, 2006): knowledge is formed through

active social interaction and communication where

shared experience is developed; learner builds during

the learning process a new understanding and concept

of the learning environment.

The important role of the paradigm of con-

structivism for the functioning of the digital edu-

cational environment is pointed out by Tchoshanov

(Tchoshanov, 2013). Lee and Lin (Lee and Lin, 2009)

demonstrate the paradigm application in the context

of distance and blended learning emphasizing that

the aim of any methodological system is not trans-

fer of knowledge in a ready form but creation of ped-

agogical conditions for successful self-development

of learners according to their own educational tra-

jectory. In addition, the paradigm of constructivism

is characterized by personal orientation and respect

for students, promoting independence, teamwork, at-

tention to the formation and development of skills to

solve problems of different sources (Dagar and Yadav,

2016), i.e. flexible skills or skills of the XXI century.

Note that STEM education, as well as the method

of M. Montessori, in addition to scientific and tech-

Methodology of M. Montessori as the Basis of Early Formation of STEM Skills of Pupils

213

Figure 1: Search for Montessori centers in the city of Zhytomyr using the search and mapping service Google Maps.

nological components of education, focused on cre-

ative development of personality, critical thinking, in-

dependence in decision-making, empathy for society

and other characteristics that are key skills of the XXI

century.

Another important feature characteristic of the

STEM / STREAM approach in teaching and meth-

ods of M. Montessori is the use of toys (from sim-

ple to technically and technologically oriented) and

game techniques to acquire new knowledge and skills

(Marshall, 2017). They teach to master the laws of

nature, the idea of how our world works and how to

explore the surrounding space, first of all, by impro-

vised means. In general, the gamification of the edu-

cational process is one of the driving forces of these

learning technologies (Buzko et al., 2018; Fedorenko

et al., 2021).

4.2 Analysis of Web Mapping Data

About Montessori Centers in

Ukraine

The compliance of educational service centers was

checked by researching the content of the Institutions

site. Based on a detailed analysis of all the results pro-

vided by the system for each of the inquiries and the

separation of those that do not use the principles of the

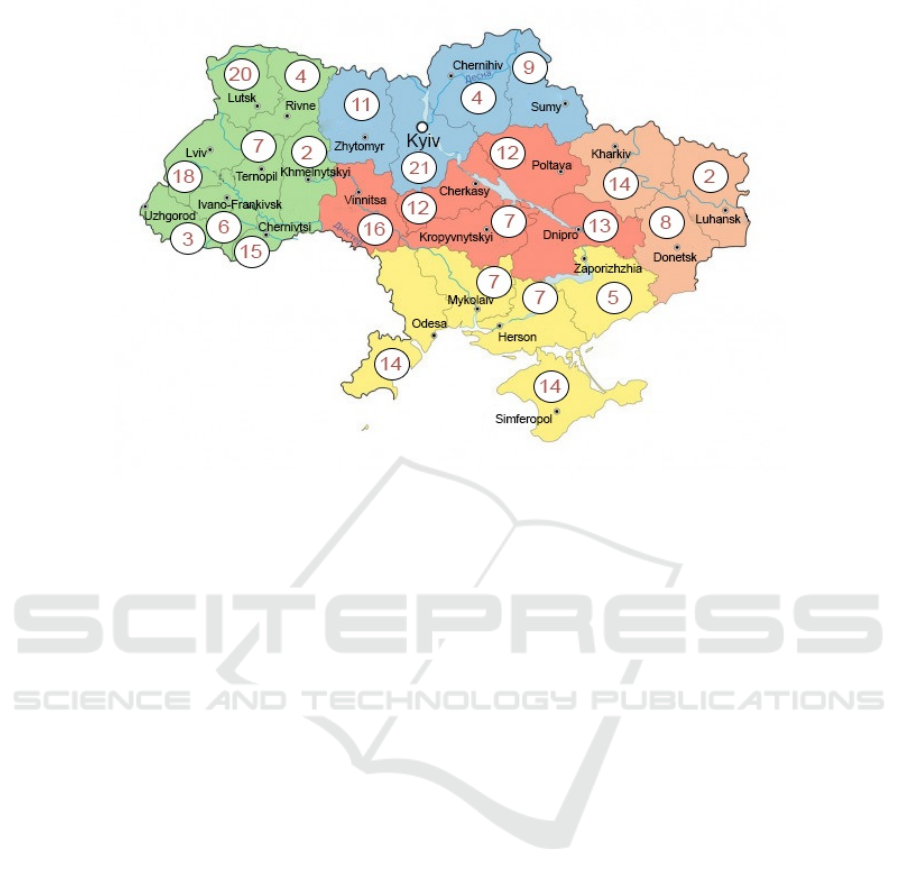

pedagogical system of M. Montessori, a map showing

all institutions of formal and non-formal education of

public and private property that fully or partially de-

clare the use of these principles of learning was drawn

up (figure 2).

As can be seen in figure 2, the largest number of

Montessori centers operating in Ukraine is concen-

trated in the capital and western regions (Lviv and

Volyn), the smallest part is determined in the east-

ern regions of the country. The study showed that

there are 60 centers in the central regions, 24 in the

eastern regions, 75 in the western regions, 45 in the

northern regions, and 47 in the southern regions. The

significant number of Montessori centers in Kharkiv

(14) and Cherkasy (12) regions is obviously due to

the presence of powerful centers in these regions such

as pedagogical universities. This method is the least

popular in Luhansk, Zakarpattia and Khmelnytsky re-

gions.

In order to identify the features of modern edu-

cational environments of M. Montessori schools, we

analyzed the online content of the proposals of such

educational centers, which are highly valued by net-

work users (one example from the relevant region

of Ukraine). Let us briefly consider the educational

proposals of some of them. Thus, the Center for

Child Development mini-kindergarten “Lviv Montes-

sori School” implements a program for children 6–

12 years old and is a full-time educational institu-

tion where, in addition to standard subjects, chil-

dren study supplementary subjects: physics, chem-

istry, worldview, art of photography, painting, chore-

ography, piano, and have thematic excursions (Face-

book, 2021b). An important feature of the pedagogi-

cal methodology of this school, as stated on the web-

site of this educational institution, is the use of ac-

tive self-assessment by pupils, cooperation (children

of different ages spend a significant amount of time

together, they have to work together to solve differ-

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

214

Figure 2: Distribution of Montessori pedagogy centers in Ukraine.

ent problems). Based on this, pupils do not get ready

for the sake of assessments, but because they are in-

terested in learning and exploring the world around

them.

Another example of effective implementation

of Montessori’s ideas in practice is the program

of the Center for Child Development “Anthill” in

Ternopil, which combines traditional forms and meth-

ods of working with younger pupils and the so-called

“events” in a prepared environment where pupils can

choose activities, interact with children of other ages,

independently study the objects of this environment

(Facebook, 2021a).

Montessori New Age School has a “Montessori

class”, which is equipped with a complete set of

Montessori materials for comprehensive and harmo-

nious development of children and is divided, like the

STEM learning space, into several functional areas;

some of them are designed to develop a variety of

practical skills, improve motor skills and coordina-

tion. Also, there are materials for the development of

sensory sensations, speech, mathematical abilities, as

well as acquaintance with the world around (Montes-

sori New Age School, 2021). It is also emphasized

the importance of the role of the teacher: “conducts

constant observation and ... knows at what stage of

development each child is, what occupation should be

offered to him for a further step forward”. Attention

is drawn to the significance of the mixed-age groups

of Montessori New Age School, which creates opti-

mal conditions for the social upbringing of children

on the principle of a large family and folk pedagogy.

The mission of the New Age School is to create a spe-

cial educational environment in which children learn

through their own experiences and feelings.

The study showed that the activities of Montes-

sori pedagogy centers in Ukraine are mainly fo-

cused on the education and training of preschool chil-

dren. Some example is the Montessori World full

cycle school in Kharkiv (montessoriya.kh.ua, 2021),

which uses an interdisciplinary approach to designing

courses and curriculum subjects with a special em-

phasis on preparing children through practical activi-

ties for real life. Among the training courses are the

following: writing and project activities (for example,

spelling is studied on topics that interest children: hu-

man structure, animal habitat, rivers or volcanoes of

different continents); publication of a school newspa-

per studies to keep the audience’s attention, present

the project, ask questions, gain experience in public

speaking. Due to special manuals and didactic mate-

rials, children can divide the whole into parts, solve

geometric problems and prove theorems. The course

“Physics, Chemistry, Astronomy” is aimed primarily

at experimental activities, creating projects that are

the foundation for in-depth study of these sciences at

high school, the course “History and Geography” uses

elements of museum pedagogy. Communicating with

teachers of Karazin University in classes on “Botany

and Zoology”, children observe plants and insects,

care for animals in their own “living space” and grow

plants. During classes “Financial knowledge and

Methodology of M. Montessori as the Basis of Early Formation of STEM Skills of Pupils

215

management” pupils learn to put financial and eco-

nomic aims, manage finances and plan a budget, in

particular, through outings, excursions, teamwork at

fairs, holidays, purchasing products. The course “Art

and Painting” includes regular master classes on felt-

ing wool, origami, etc. Besides, it is aimed at de-

veloping practical life skills and social responsibility:

children develop menus, prepare dinners, set the ta-

ble, wash dishes, clean the classrooms, clean up the

forest of rubbish, sort garbage, and hand over waste

paper. In this Montessori environment, pupils partic-

ipate individually and in groups. Classes are divided

into thematic areas: mathematics, languages, geog-

raphy, history, biology, space; there is a laboratory.

Due to this the learning approach is realized: teach

the child to think, find solutions, make discoveries,

search for information and be able to apply it when

needed.

It should be noted that most educational institu-

tions that use Montessori’s ideas are private, such as

the Clever Kids Elementary School in Kyiv. In addi-

tion to the annual curriculum in accordance with the

standard, for each child, taking into account the gifts

and flaws of the pupil, his abilities, main interests,

age goals, phase of character development, and level

of ability to control emotions and interact with the

team is worked out a personalized curriculum (Clever

Kids, 2021). Particular attention is paid to the forma-

tion of project activities skills that promote children’s

interest in research, skills of planning and organiz-

ing their working time, critical, analytical and abstract

thinking skills, and teamwork. Among the pedagog-

ical tasks of the Clever Kids are also assistance in

the pupil potential development, development of in-

dependence and self-sufficiency of thinking, respect

and empathy for others, responsibility and leadership

qualities. There are created conditions for the devel-

opment of children based on their individual step and

biological rhythm, formation of skills of independent

work, promoting the initiative in the choice of ma-

terials, stimulating the development of self-discipline

skills, cooperation with parents and more. Emphasis

is placed on the importance of the activities of teach-

ers, whose mission is to find ways to inspire children

to learn. Such support allows children, first of all,

to gain confidence and strive to perform tasks con-

stantly without fear of failure. Emphasis is placed on

the gradual complication of tasks, which creates op-

portunities to go through the process of aim setting

and experience of personal victory.

Thus, the study of information about Montessori

education centers in Ukraine showed that the modern

interpretation of pedagogical postulates for socializa-

tion and upbringing of the child is indisputable and

can resolve the contradictions associated with the im-

plementation in practice of the basic requirements for

the modern educational process: individualization, re-

liance on sensitive periods, the priority of personal in-

dependence, the ability to make choices and respect

the choices of others, freedom and discipline in dif-

ferent age communication, etc.

Our study showed that there are more than 250

educational institutions in Ukraine that use the meth-

ods and principles of teaching Maria Montessori.

For comparison, in Germany there are about 1000

preschool institutions and 400 schools operating on

the basis of Montessori pedagogy: gymnasiums are

40 percent, general schools – 25%, primary – 20%

and real schools – 15% (Priboschek, 2020). Thus, the

ideas and pedagogical system of M. Montessori re-

main relevant in the education of the XXI century.

4.3 Analysis of Web Mapping Data

About STEM-STEAM-STREAM

Centers in Ukraine

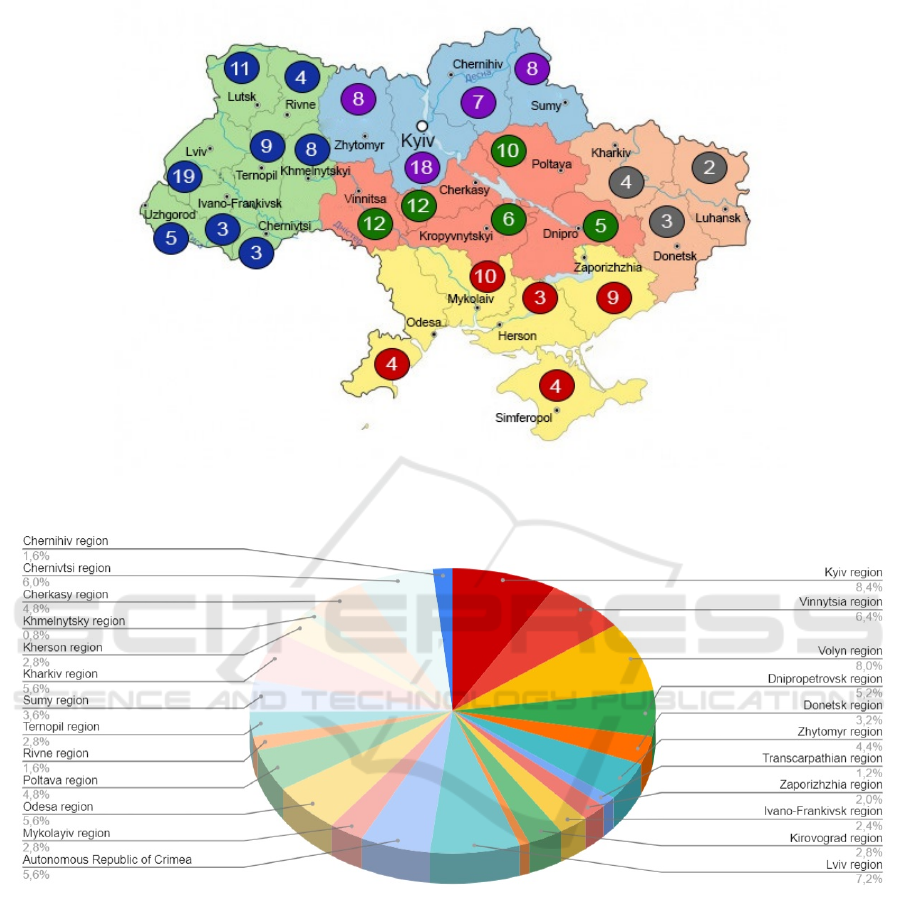

For comparison, a map of the development of STEM-

STEAM-STREAM centers was created in a similar

way (figure 3).

Our research showed that there are more than 190

teaching centers in Ukraine that use STEM-STEAM-

STREAM technologies. 45 STEM centers are func-

tioning in the central regions, 9 centers in the east re-

gions, 62 centers in the western regions, 41 centers

in the northern regions, 30 centers in the southern re-

gions. This is due to the fact that STEM education in

Ukraine is only gaining popularity, and their largest

number we have only in large cities (Kiev, Lviv). The

smallest number of STEM institutions is located in

the eastern and southwestern regions.

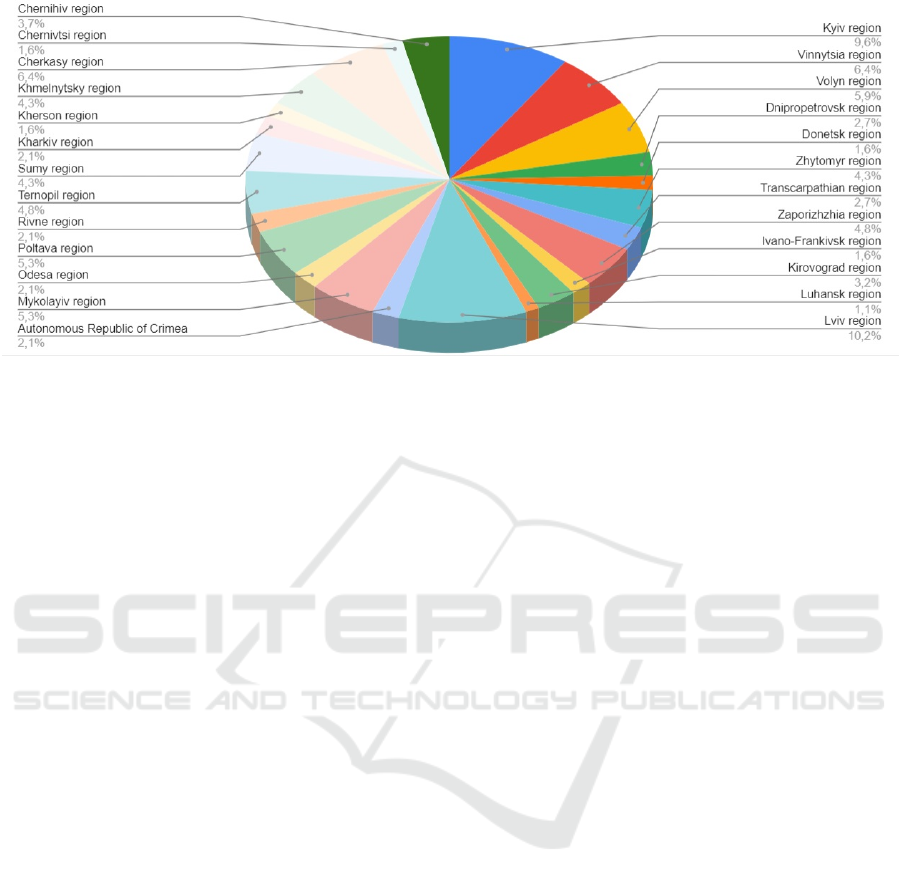

The obtained data on the development of educa-

tional centers in Ukraine based on the pedagogy of

M. Montessori and STEM-STEAM-STREAM cen-

ters are presented in the form of diagrams (figures 4,

5).

The development of Montessori pedagogy, which

is presented on figure 4, shows that the Montessori

concept is widely known in Ukraine. Nonetheless,

since this practice is used only by private schools

and kindergartens, it is not available for many chil-

dren and its percentage is small in some regions. The

largest centers and networks of STEM centers and

Montessori schools are located in Kyiv.

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

216

Figure 3: STEM-STEAM-STREAM centers in Ukraine.

Figure 4: Quantitative distribution of Montessori pedagogy centers in Ukraine.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The analysis of the peculiarities of M. Montessori

methodology and STEM approach in education re-

vealed their common origins from the constructivist

philosophy in education. The relevance of these

ways in formal and non-formal education in Ukraine

is demonstrated by investigation using web mapping

service Google Maps. It creates grounds for the con-

clusion about the possibility of their harmonious com-

plement: organizational and pedagogical condition of

their operation is creation a special learning environ-

ment capable to adaptation to personal ideals and cog-

nitive needs of participants of the educational process

favorable in the context of the development of soft

skills (Sultanova et al., 2021; Varava et al., 2021).

We have noted supplementary didactic features of

Montessori technology characteristic for STEM tech-

nologies:

• focus on the formation of a permanent interest to

the processes and phenomena in the world, the

development of curiosity based on research us-

ing the steps characteristic to the scientific method

and the process of engineering design;

Methodology of M. Montessori as the Basis of Early Formation of STEM Skills of Pupils

217

Figure 5: Quantitative distribution of STEM-STEAM-STREAM centers in Ukraine.

• changing the role of the teacher, shifting the

emphasis to motivation for productive activities,

stimulating development, creating a pedagogical

ecosystem of formation the scientific picture of

the world in the minds of students and, at the same

time, key skills of the XXI century.

A comparison of the created maps provides

grounds for concluding that the Montessori method-

ological system has adapted to the rapid development

of machinery and technology in the XXI century; the

popularity of STEM educational centers is growing

rapidly in Ukraine (almost 200 new centers in 10

years). The use of the Gartner Hype Cycle method

to describe this process (Gartner, 2019) suggests that

Montessori pedagogy is now on a “plateau of produc-

tivity” and that STEM approaches in education are in

a state of active implementation, which corresponds

to “innovation trigger” and approach the “peak of in-

flated expectations”.

STEM technologies of teaching and pedagogical

ideas of M. Montessori harmoniously complement

each other, especially in the context of forming the

ability to successful self-development based on main-

taining the relationship between the child and the de-

velopmental subject-spatial environment (M. Montes-

sori), which at the present time can be digital (STEM).

REFERENCES

Allen, R. (1913). The Montessori method and missionary

methods. International Review of Mission, 2(2):329–

341.

Argy, W. (1965). Montessori versus orthodox; a study to

determine the relative improvement of the preschool

child with brain damage trained by one of the two

methods. Rehabilitation literature, 26(10):294–304.

Bada, S. (2015). Constructivism learning theory: A

paradigm for teaching and learning. IOSR Journal of

Research & Method in Education, 1(5).

Beatty, B. (2011). The dilemma of scripted instruction:

Comparing teacher autonomy, fidelity, and resistance

in the Froebelian kindergarten, Montessori, direct

instruction, and success for all. Teachers College

Record, 113(3):395–430.

Beck, R. (1961). Kilpatrick’s critique of Montessori’s

method and theory. Studies in Philosophy and Edu-

cation, 1(4-5):153–162.

Buzko, V., Bonk, A., and Tron, V. (2018). Implementa-

tion of gamification and elements of augmented real-

ity during the binary lessons in a secondary school.

CEUR Workshop Proceedings, 2257:53–60.

Claremont, C. (1952). In Memory of Dr. Montessori.

British Medical Journal, 1(4771):1304.

Clever Kids (2021). Private elementary school and kinder-

garten Clever Kids. https://cleverkids.com.ua.

Cohen, S. (1968). Educating the children of the urban poor:

Maria Montessori and her method. Education and Ur-

ban Society, 1(1):61–79.

Dagar, V. and Yadav, A. (2016). Constructivism: A

paradigm for teaching and learning. Arts and Social

Sciences Journal, 7(4).

Denny, T. (1965). Montessori resurrected: Now what? Ed-

ucational Forum, 29(4):436–441.

Denny, T. (1966). Once upon a Montessori. Educational

Forum, 30(4):513–516.

Dodd-Nufrio, A. (2011). Reggio Emilia, Maria Montes-

sori, and John Dewey: Dispelling Teachers’ Miscon-

ceptions and Understanding Theoretical Foundations.

Early Childhood Education Journal, 39(4):235–237.

Dohrmann, K., Nishida, T., Gartner, A., Lipsky, D., and

Grimm, K. (2007). High school outcomes for students

in a public Montessori program. Journal of Research

in Childhood Education, 22(2):205–217.

Drenckhahn, F. (1961). Montessori materials and the teach-

ing of mathematics. International Review of Educa-

tion, 7(2):174–186.

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

218

Dychkivska, I. and Ponymanska, T. (2009). Montessori:

Theory and technology. Slovo Publishing House.

Edgington, R. (1970). For the classroom: Montessori and

the teacher of children with learning disabilities: A

personnel odyssey. Intervention in School and Clinic,

5(3):219–221.

Edwards, C. (2002). Three approaches from Europe: Wal-

dorf, Montessori, and Reggio Emilia. Early Child-

hood Research and Practice, 4(1).

Facebook (2021a). Child development center Murashnyk.

https://www.facebook.com/murashnyk.

Facebook (2021b). Lviv Montessori School.

https://www.facebook.com/LvivMontessoriSchool/.

Fedorenko, E. G., Kaidan, N. V., Velychko, V. Y., and

Soloviev, V. N. (2021). Gamification when study-

ing logical operators on the Minecraft EDU platform.

CEUR Workshop Proceedings, 2898:107–118.

Gartner (2019). Hype cycle for education.

https://learn.extremenetworks.com/Gartner-Hype-

Cycle-for-Education-2019.html.

Gitter, L. (1967a). Montessori principles applied in a class

of mentally retarded children. Mental Retardation,

5(1):26–29.

Gitter, L. (1967b). The promise of Montessori for special

education. Journal of Special Education, 2(1):5–13.

Gitter, L. (1970). A centenary for Montessori. Intervention

in School and Clinic, 5(4):247–248.

IMZO (2016). Institute for Modernization of

the Content of Education: STEM-education.

https://imzo.gov.ua/stem-osvita/.

Komar, O. (2006). Constructivist paradigm of education.

Philosophy of education, 2:36–45.

Kramarenko, T., Pylypenko, O., and Zaselskiy, V. (2020).

Prospects of using the augmented reality application

in STEM-based Mathematics teaching. CEUR Work-

shop Proceedings, 2547:130–144.

Krutiy, K. and Hrytsyshyna, T. (2016). STREAM-education

of preschool children: We bring up the culture of en-

gineering thinking. Preschool Education, (1):3–7.

Lapon, E. (2020). Montessori middle school and the tran-

sition to high school: Student narratives. Journal of

Montessori Research, 2(6).

Lee, J. and Lin, L. (2009). Applying constructivism to on-

line learning. Information Technology and Construc-

tivism in Higher Education.

Levy, D. and Bartelme, P. (1927). The measurement of

achievement in a Montessori school and the intelli-

gence quotient. Pedagogical Seminary and Journal

of Genetic Psychology, 34(1):77–89.

Lillard, A. (2012). Preschool children’s development in

classic Montessori, supplemented montessori, and

conventional programs. Journal of School Psychol-

ogy, 50(3):379–401.

Lillard, A. and Else-Quest, N. (2006). Evaluating Montes-

sori education. Science, 313(5795):1893–1894.

Lillard, A., Heise, M., Richey, E., Tong, X., Hart, A., and

Bray, P. (2017). Montessori preschool elevates and

equalizes child outcomes: A longitudinal study. Fron-

tiers in Psychology, 8(OCT):1783.

Lopata, C., Wallace, N., and Finn, K. (2005). Comparison

of academic achievement between Montessori and tra-

ditional education programs. Journal of Research in

Childhood Education, 20(1):5–13.

Marshall, C. (2017). Montessori education: a review of the

evidence base. Science Learn, 2(11).

Mavric, M. (2020). The Montessori approach as a model of

personalized instruction. Journal of Montessori Re-

search, 6(2).

Montessori, M. (1961). Maria Montessori’s contribution

to the cultivation of the mathematical mind. Interna-

tional Review of Education, 7(2):134–141.

Montessori New Age School (2021). Montessori new age

school. http://mnas.com.ua/course-details.html.

montessoriya.kh.ua (2021). The world of Montessori. Al-

ternative education according to the Montessori sys-

tem of the full cycle. http://montessoriya.kh.ua/.

Morra, M. (1967). The Montessori method in the light of

contemporary views of learning and motivation. Psy-

chology in the Schools, 4(1):48–53.

Paton, L. (1915). Montessori education for children with

defective sight. Journal of the Royal Society of

Medicine, 8(Sect Ophthalmol):100–106.

Piaget, J. (1980). The psychogenesis of knowledge and its

epistemological significance. In Piattelli-Palmarini,

M., editor, Language and Learning: The Debate Be-

tween Jean Piaget and Noam Chomsky, pages 1–23.

Harvard University Press.

Priboschek, A. (2020). 150. Geburtstag von Maria Montes-

sori – Warum ihre P

¨

adagogik heute noch so wichtig

ist. https://www.news4teachers.de/2020/08/150-

geburtstag-von-maria-montessori-warum-ihre-

paedagogik-heute-noch-so-wichtig-ist/.

Rathunde, K. and Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2005). Mid-

dle school students’ motivation and quality of expe-

rience: A comparison of Montessori and traditional

school environments. American Journal of Education,

111(3):341–371.

Roeper, A. (1966). Gifted preschooler and the Montessori

method. Gifted Child Quarterly, 10(2):83–89.

Smith, T. (1911). Dr. Maria Montessori and her houses of

childhood. Pedagogical Seminary, 18(4):533–542.

Stendler, C. (1965). The Montessori method. Educational

Forum, 29(4):431–435.

Stern, K. (1930). Beobachtungen des Spontanverhal-

tens vorschulpflichtiger Kinder

¨

uber lange Zeitinter-

valle im Montessori-Kinderhause. Psychologische

Forschung, 13(1):79–100.

Stetsenko, I. (2016). Substantiation of the need for tran-

sition from STEM-education to STREAM-education

in preschool age. Computer in School and Family,

(8):31–34. http://nbuv.gov.ua/UJRN/komp 2016 8 8.

Sultanova, L., Hordiienko, V., Romanova, G., and Tsyt-

siura, K. (2021). Development of soft skills of teach-

ers of physics and mathematics. Journal of Physics:

Conference Series, 1840(1):012038.

Tchoshanov, M. (2013). Engineering of Learning: Concep-

tualizing e-Didactics. UNESCO Institute for Informa-

tion Technologies in Education, Moscow. https://iite.

unesco.org/pics/publications/en/files/3214730.pdf.

Methodology of M. Montessori as the Basis of Early Formation of STEM Skills of Pupils

219

Varava, I. P., Bohinska, A. P., Vakaliuk, T. A., and Mintii,

I. S. (2021). Soft skills in software engineering tech-

nicians education. Journal of Physics: Conference Se-

ries, 1946(1):012012.

Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (2017). Law of Ukraine

On Education. https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/

2145-19#Text.

von Glasersfeld, E. (1995). A constructivist approach to

teaching. In Steffe, L. P. and Gale, J., editors, Con-

structivism in education.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1962). Thought and language. MIT Press,

Cambridge, MA.

Whitesgarver, K. and Cossentino, J. (2008). Montessori and

the mainstream: A century of reform on the margins.

Teachers College Record, 110(12):2571–2600.

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

220