Structural Equation Modeling in Educational Research: A Case-study

for PhD Training

Liubov F. Panchenko

1 a

and Vladyslav Ye. Velychko

2 b

1

National Technical University of Ukraine “Igor Sikorsky Kyiv Polytechnic Institute”, 37 Peremohy Ave., Kyiv, 03056,

Ukraine

2

Donbass State Pedagogical University, 19 Henerala Batiuka Str., Sloviansk, 84116, Ukraine

Keywords:

Structure Equation Modelling, TALIS Methodology, Ukrainian Teachers, Teacher’s Self-Efficacy, PhD

Student, AMOS, R.

Abstract:

The article deals with the problem of using structural equation modelling (SEM) methodology in educational

research. It allows the researcher to build multidimensional models of the phenomena and processes that are

being studied. The SEM methodology is based on many well-known methods such as correlation, regression,

factor analysis, variance analysis and covariance analysis. The methodology is mainly based on deductive

logic, involves the preliminary construction of a structural model of relationships between variables in order

to further check for consistency with the experimental data. The article summarizes the use of various SEM

software in the training of doctors of philosophy of the world’s leading universities and provides an example

of using the SEM methodology in educational research for PhD student training. An important point in prepar-

ing specialists for using SEM is to select or obtain the necessary data sets that are representative and valid.

During the research the Ukrainian teacher’s self-efficacy model with SEM methodology was checked, and

the obtained results were compared with the research data of the worldwide teacher’s survey – The Teaching

and Learning International Survey (TALIS). The lower self-efficacy of Ukrainian teachers, especially in the

student engagement block, was showed.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Setting of a Problem

In recent years, many PhD programs were organized

in Ukraine. Qualitative scientific research is impos-

sible without a systematic description of the stud-

ied phenomena; multidimensionality of the investi-

gated phenomena requires the use of multidimen-

sional analysis methods that are capable to identify

causal relationships, latent factors, etc. A promising

area in the field of multidimensional applied analy-

sis is the structural modeling or structural equation

modeling, which is becoming an increasingly popular

tool for researchers in the field of education, psychol-

ogy and social sciences (Kline, 2015; Khine, 2013;

Mitina, 2008; Nasledov, 2013; Chornyi, 2011).

In our article (Panchenko et al., 2021) the three fo-

cuses of the research component of doctoral program

are proposed. The first focus relates to reproducible

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9979-0625

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9752-0907

research principle. The second focus is related to

the use of multivariate models of phenomena’s study

and SEM methodology. The SEM methodology is

mostly based on deductive logic, involves the prelimi-

nary construction of a structural model of the relation-

ships between the variables in order to further check

for consistency with the experimental data. The third

focus combines qualitative and quantitative methods

and the use of triangulation (data triangulation, inves-

tigation triangulation, theory triangulation etc.). The

content of selected courses for doctorate students is

proposed: Reproducible Research and Multivariate

Methods in Scientific Research courses.

In this article, we focus on the SEM methodology;

we consider it very important to train future doctors of

philosophy to use it in the educational research.

The popularity of the SEM methodology is ev-

idenced by the experiment we conducted. At the

request of “structural equation modeling” to search

books on Amazon.com (as of March 16, 2013), we

obtained 59 items, the graph of which is clearly shown

in figure 1. In the center of the graph (figure 1, on

300

Panchenko, L. and Velychko, V.

Structural Equation Modeling in Educational Research: A Case-study for PhD Training.

DOI: 10.5220/0010923900003364

In Proceedings of the 1st Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology (AET 2020) - Volume 1, pages 300-307

ISBN: 978-989-758-558-6

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

the left), where 5 subgraphs can be observed, there is

the third edition of the bestseller, Principles and Prac-

tice of Modeling by Structural Equations by Kline

(Kline, 2015). The companion site of this publication

provides methodological support and offers download

syntax, data and source files for all sample books for

execution in three environments EQS, LISREL and

Mplus, and a comparison of simulation results. A

similar experiment, conducted on March 28, 2019

(figure 1, on the right), shows interest growth in struc-

tural modeling; we have 157 items. Interestingly, the

fourth edition of the same bestseller has the biggest

rating there.

Figure 1: Books on “ structural equation modeling”, Ama-

zon.com, year 2013 versus 2019.

While solving the scientific problem of training

PhDs to use the SEM methodology, the following

main results were obtained in past author works: the

content of the simulation training by the structural

equations of specialists in the field of education is re-

vealed; the dynamics of software simulation by struc-

tural equations is analyzed; the necessity of including

these means in the courses for students and graduates

of higher educational institutions of Ukraine that spe-

cialize in the field of education and social sciences is

substantiated (Panchenko, 2013).

The syllabuses of PhD SEM courses of lead-

ing universities are analyzed (Higher School of Eco-

nomics, St. Petersburg; University of Amster-

dam; University of Vaasa, Finland; University of

Mannheim; Iowa State University; Brown University;

University of Leuven; School of Education University

of Pittsburgh; Oslo University etc).

An analysis of the best PhD programs in sociol-

ogy according to the Princeton Review’s “Gourman

Report of Graduate Programs” (Plous, 2021) showed

that they must have courses on structural equation

modelling. In table 1, we summarize the use of var-

ious SEM software in the training of doctors of phi-

losophy of the world’s leading universities.

Analysis of syllabusis (table 1) showed that in

general the courses are organized in the format of

seminars. The main activity is created at the intersec-

tion of lectures, group discussions, software applica-

tion and interpretation of results. Teaching materials

are available through the Blackboard or Moodle learn-

ing management system. The number of course cred-

its ranges from 1 to 6 with 1–3 credits for introductory

courses, and 4–6 credits for advanced. Courses are of-

fered as part of the training of doctors of philosophy

in the field of pedagogy, psychology, sociology, statis-

tics, information systems and business, public health,

sports, etc. Both proprietary and free software is used.

In most courses, one software tool is acting as the

main tool, and another one as an additional. But there

are courses in which several software tools are widely

used.

Here is an example of evaluating the work of

students in the course (www.soc.iastate.edu, 2021).

Homework with the use statistical software: 8%; crit-

ical review of articles on the topic (4 reviews of 4–5

pages): 30%; statistical analysis (4 reports of 12–15

pages): 62%. For a critical review, the parameters

of its evaluation are given: for example, to explain

the basic model that the author evaluates (20% of the

mark); discussion of critical mistakes made by the au-

thor (40%); an explanation of how the casual effect

(40%) can be correctly estimated. Some programs of-

fer an exam and a final project during the course as

their own mini-study on the use of SEM.

The objectives of the SEM courses are defined as

follows: using structural equation modeling method-

ology to study the problems of social and behavioral

science, understanding the strengths and flaws of the

method and its limitations, teaching methods of as-

sessment, identification models, testing their validity,

interpretation, critical evaluation of scientific publi-

cations on this subject, using statistical software to

perform structural equation modeling analysis, prepa-

ration of research reports in accordance with the stan-

dards of research (Panchenko and Razoronova, 2016).

In preparing specialists for using SEM an im-

portant point is to select or obtain the necessary

data sets that are representative and valid. We offer

our students the survey data from Ukrainian teachers

(Shchudlo et al., 2018; TALIS, 2017; Questionnaires,

2017).

On August 31, 2017, the Ukrainian Associa-

tion of Educational Researchers completed the All-

Ukrainian monitoring “Teaching and Learning Sur-

vey on Principals and Teachers of Secondary Edu-

cation Institutions” (based on the TALIS methodol-

ogy (OECD, 2018). The study was conducted within

the framework of the project “Teacher” and “Edu-

cation Reform: Quality Assessment in an Interna-

tional Context”, which is implemented by the All-

Ukrainian Foundation “Step by Step” with the support

of the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine

(Shchudlo et al., 2018). The study was attended by

Structural Equation Modeling in Educational Research: A Case-study for PhD Training

301

Table 1: Software in SEM courses.

Software

Course name AMOS

SPSS

EQS Mplus Lisrel Open Mx SAS R

”Modern Social Analysis”, HSE, St. Peters-

burg

+

”Structural equation modelling in educational

research”, University of Amsterdam

+ + +

”Latent Structural Equation Modeling”, Uni-

versity of Vaasa, Finland

+ + + + +

SEM1, University of Oregon + +

”Structural equation modelling using LISREL

and EQS” (SEM PhD workshop)

+ +

”Structural Equation Modeling in the IS Dis-

cipline”, University of Mannheim

smart

PLS

”Structural equation models for social and be-

havioral research”, Iowa State University

”Structural Equation Models in the Social Sci-

ences”, University of Brown

+

”Causal analysis and structural equation mod-

eling”

+ Stata

”Structural Equations”, University of Leuven,

PhD in Statictics

+

”Structural Equation Modeling”, School of

Education University of Pittsburgh

+ +

”Structural equation modeling: Longitudinal

models and multi-group models”, University

of Oslo

+

”Building and Testing Structural Equation

Models In the Social Sciences”, University of

Michigan

+ + +

”An introduction to structural equation mod-

elling”, Doctoral college of Ulster University

”PhD-M: Structural Equations Modeling”,

University of Vienna

+

PSY9140 -– ”Structural Equation Modelling”,

Oslo university

+ +

PSY8006 — ”Introduction to Structural Equa-

tion Modeling (with MPlus)”, Norwegian uni-

versity of science and technology

+

Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling

(Sem), PhD School of Copenhagen Business

School

+

Structural Equation Modeling, HSE, Russia +

3,600 teachers and 201 school principals from 201

schools, representing all regions of Ukraine. The re-

sults of the study, according to the OECD policy, are

open and accessible.

The purpose of our article is to show the ways to

apply the SEM methodology in educational research

for PhD students. In our case-study, we will, based

on the survey data of Ukrainian teachers, check the

model of teacher’s self-efficacy with SEM methodol-

ogy, and compare obtained results with the research

data of the worldwide teacher’s survey – TALIS.

1.2 Related Works

The methodology of structural modeling has received

wide recognition in the global community. The study

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

302

of the basics of structural modeling has become a

component of the training of researchers specializ-

ing in social sciences (Panchenko and Razoronova,

2016). In Russia, the ideas of structural modeling in

relation to psychology are reflected in (Mitina, 2008;

Nasledov, 2013). The use of SEM with an emphasis

on economic research has been studied by Chornyi

(Chornyi, 2011). Unfortunately, in Ukraine, struc-

tural modeling is not sufficiently used in educational

and social studies in general, and in the training of

researchers at universities, in particular.

The aspects of the application of the SEM method-

ology to educational data (TALIS, 2013) are devoted

to the following research. A structural equation model

of determinants of the perceived impact of teachers’

professional development (the Abu Dhabi applica-

tion) is reviewed by Badri et al. (Badri et al., 2017).

How school context and teacher’s characteristics pre-

dict distributed leadership is presented by Liu et al.

(Liu et al., 2018). The invariance of teachers’ sense

of self-efficacy measured across countries is reviewed

by Scherer et al. (Scherer et al., 2016).

2 RESULTS OF THE STUDY

TALIS (Teaching and Learning International Survey)

is one of the most prestigious international compar-

ative education projects. The project is dedicated

to studying the environment and work conditions of

school teachers. It has been implemented since 2008

by a research consortium under the Organization for

Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

24 OECP countries and partner countries participated

in the first wave of TALIS study in 2008, 34 – in the

second wave in 2013, and 44 countries plan to partic-

ipate in 2018 (Shchudlo et al., 2018; OECD, 2018).

All-Ukrainian monitoring survey of teaching and

learning among school principals and teachers of gen-

eral educational institutions (according to the method-

ology All-Ukrainian research on TALIS methodol-

ogy) is an example of use of international instruments

for studying national educational space and identi-

fying the place of the Ukrainian teacher community

in the international community educational context.

The purpose of the research is to identify and ana-

lyze socio-demographic and professional characteris-

tics of Ukrainian teachers and academic staff and the

environment of schools on the basis of reliable com-

parable metrics (Shchudlo et al., 2018).

3600 teachers of 5–9 grades of secondary schools

(level ISCED 2) and 201 school principals from 201

schools participated in the survey in 2017. Error of

simple random sampling is 1.6%, the school sam-

ple selection error takes into account design effect is

2.3%.

From the Ukrainian teacher’s survey file (TALIS,

2017) we selected 3477 lines without missing values

for 12 variables that represented the teacher’s self-

efficacy (table 2).

Bandura (Bandura, 1982) defines self-efficacy as

a personal judgment of “how well one can execute

courses of action required to deal with prospective

situations”. He names four sources of efficacy be-

liefs: 1) mastery experiences; 2) vicarious experi-

ences; 3) verbal persuasion; 4) emotional and phys-

iological states.

Professional teacher’s self-efficacy, in general, is

the perception of a person’s own ability to mobilize

motivation, cognitive resources and behavioral ac-

tivity that are needed to control the situation in or-

der to achieve the intended purpose (Bandura, 1982;

Kremeshna, 2010; Krasnoryadtseva et al., 2014).

TALIS model for teacher consists of three compo-

nents of self-efficacy: self-efficacy in classroom man-

agement; self-efficacy in instruction; self-efficacy in

student engagement.

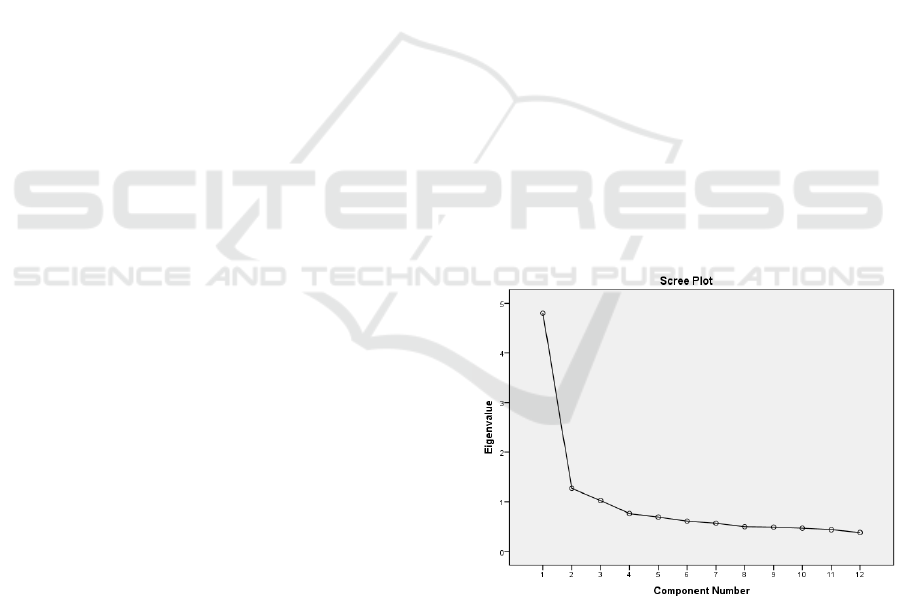

We will conduct a factor analysis for these data.

The obtained values of Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (0.902)

and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (13308, p < 0.001)

indicate that factor analysis is a suitable method for

these data. The scree plot below shows three factors

(figure 2).

Figure 2: Scree plot: a line plot of the eigenvalues of fac-

tors.

Let us consider the rotated component matrix (ta-

ble 3). It demonstrates that the first factor, loading

high factor weight of the attributes, is related to the

class management, the second one is related to the

student’s engagement, and the third one to the instruc-

tion.

You can also observe that the variable “Craft good

Structural Equation Modeling in Educational Research: A Case-study for PhD Training

303

Table 2: Variables of teacher’s self-efficacy.

Variable name Content

TT2G34A Get students to believe they can do well in school work

TT2G34B Help my students value learning

TT2G34C Craft good questions for my students

TT2G34D Control disruptive behavior in the classroom

TT2G34E Motivate students who show low interest in school work

TT2G34F Make my expectations about student behavior clear

TT2G34G Help students think critically

TT2G34H Use a variety of assessment strategies

TT2G34I Provide an alternative explanation, for example, when students are confused

TT2G34J Implement alternative instructional strategies in my classroom

TT2G34K Get students to follow classroom rules

TT2G34L Calm down a student who is disruptive or noisy

Table 3: Rotated component matrix.

Factor 1:

Class man-

agement

Factor 2:

Student En-

gagement

Factor 3:

Instruction

Control disruptive behavior in the classroom .795

Calm a student who is disruptive or noisy .773

Get students to follow classroom rules .765

Make my expectations about student behavior clear .596

Help my students value learning .816

Get students to believe they can do well in school work .764

Motivate students who show low interest in school work .644

Help students think critically .448

Craft good questions for my students .443

Provide an alternative explanation, for example, when

students are confused

.785

Implement alternative instructional strategies in my class-

room

.736

Use a variety of assessment strategies .730

questions for my students” is more related to the fac-

tor “Student engagement” than the factor “Instruc-

tion”. As you see, three factors explain 59.1% of vari-

ability (table 4).

Table 4: Total variance explained.

Component Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings

Total % of Variance Cumulative %

1 2.571 21.425 21.425

2 2.313 19.274 40.698

3 2.211 18.429 59.127

Scientists identify next five steps in SEM applica-

tion (Kline, 2015; Nasledov, 2013).

1) model formation. The model depicts the graphi-

cal views of the researcher about the structure of

the variable and latent constructs of ties. At the

same time, they decide which parameters should

be fixed, and which should be left free.

2) model identification

3) model evaluation

4) checking the consistency of the model

5) model correction by adding new links and elimi-

nating insignificant links.

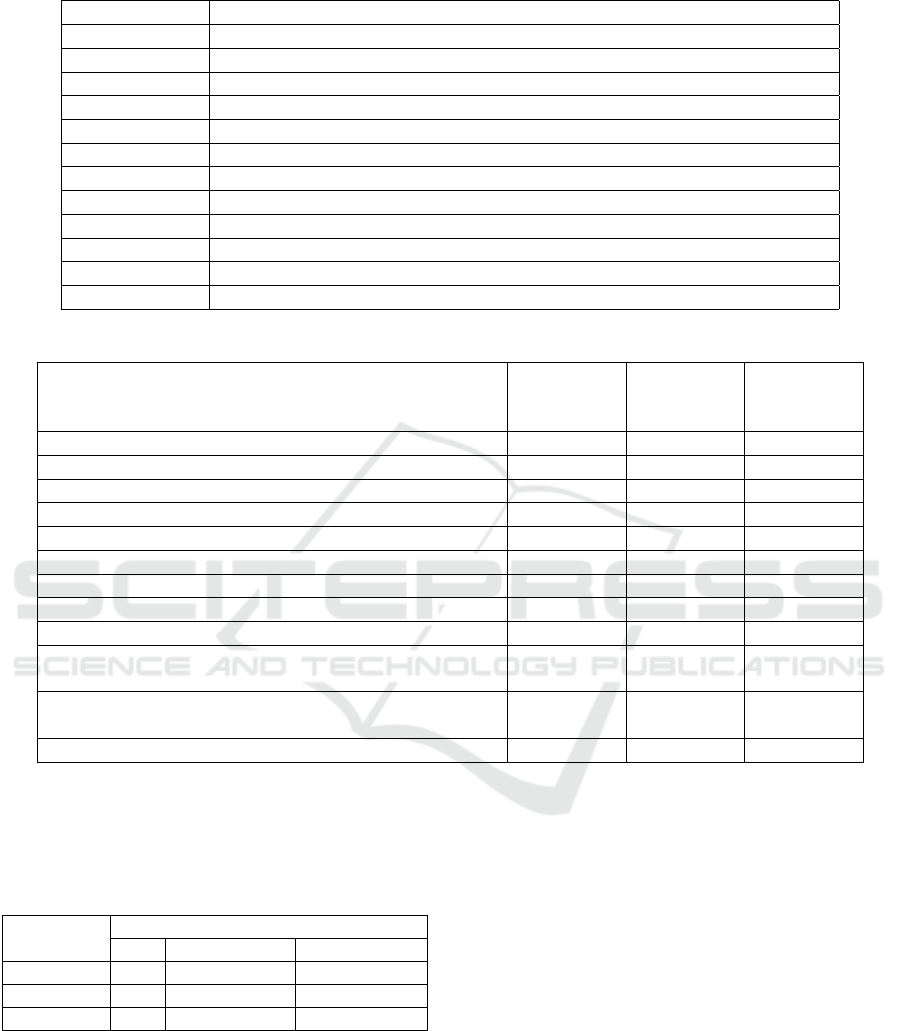

Let us build a model of confirmatory factor analy-

sis with AMOS SPSS (figure 3).

You can see the resulting teacher’s self-efficacy

model in the figure 4.

We got the following results. Number of distinct

sample moments: 78; number of distinct parameters

to be estimated: 27; degrees of freedom: 78–27=51.

Criteria for coherence RMSEA 0.07 < 0.08, that is,

the model is consistent with the data.

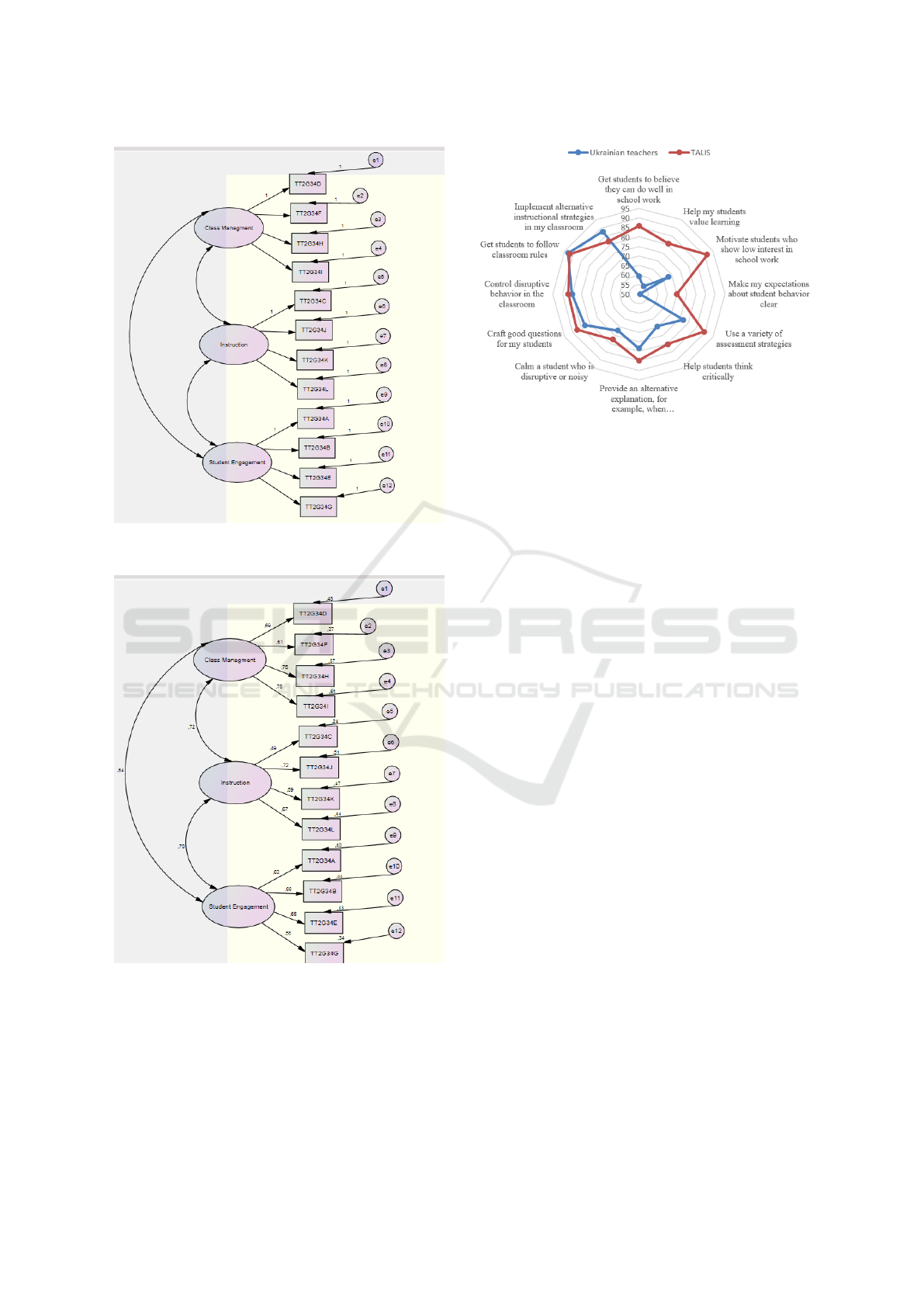

Using the data (Shchudlo et al., 2018), we clearly

compared the indicators of self-efficacy of teachers

in Ukraine and in the world (table 5, figure 5). The

graph shows that self-efficacy of Ukrainian teachers

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

304

Figure 3: Initial teacher’s self-efficacy model in AMOS

SPSS.

Figure 4: Resulting teacher’s self-efficacy model in AMOS

SPSS.

is lower, especially in the student engagement block

(variable “Get students to believe they can do well

in school work” – difference was 26.4%, ”Help my

students value learning” – 26%, ”Motivate students

who show low interest in school work” – 19.4 %).

As a continuation of the research, PhD students

Figure 5: Comparison of teachers’ self-efficacy in Ukraine

and in the world.

can be invited to analyze the results of a recently

published survey TALIS 2018. TALIS 2018 (Plous,

2021) identifies a number of factors that are related to

teacher self-efficacy:

1. Teacher characteristics: years of experience as a

teacher

2. Index of classroom disciplinary climate

3. Took part in any induction activities at current

school

4. Induction activities at current school included

team teaching with experienced teachers

5. Professional development acitivities in the 12

months prior to the survey did have a positive im-

pact on teaching practice

6. Index of workplace well-being and stress

7. Fixed-term contract: less than or one school year

8. Index of professional collaboration

9. Index of target class autonomy

This relationship does not apply to all countries

(table 6).

An interesting task for PhD students is to build the

SEM model taking into account factors of teacher’s

self-efficacy according TALIS 2018.

3 CONCLUSIONS AND

PERSPECTIVES OF FURTHER

RESEARCH

Measurements that are used in modern educational re-

search are becoming more and more complex. The

author’s vision of the research component of training

Structural Equation Modeling in Educational Research: A Case-study for PhD Training

305

Table 5: Indicators of self-efficacy of teachers in Ukraine and in the world (%).

Variables Ukrainian

teachers

TALIS Difference

A. Get students to believe they can do well in school work 59.4 85.8 26.4

B. Help my students value learning 54.7 80.7 26

C. Craft good questions for my students 82.6 87.4 4.8

D. Control disruptive behavior in the classroom 85 87 2

E. Motivate students who show low interest in school work 50.6 70 19.4

F. Make my expectations about student behavior clear 68 91.3 23.3

G. Help students think critically 69.5 80.3 10.8

H. Use a variety of assessment strategies 77 89.4 12.4

I. Provide an alternative explanation. for example. when students are confused 78.5 84.8 6.3

J. Implement alternative instructional strategies in my classroom 87.8 81.9 -5.9

K. Get students to follow classroom rules 92.9 92 -0.9

L. Calm a student who is disruptive or noisy 72 77.4 5.4

Table 6: Factor of self-efficacy of teachers in TALIS 2018 and number of countries and percentage of countries with positive

and negative relation (%).

Factor N+ %+ N- %-

Teacher characteristics: years of experience as a teacher 29 60.4 0 0

Index of classroom disciplinary climate 0 0 45 93.8

Took part in any induction activities at current school 25 52.1 0 0

Induction activities at current school included team teaching

with experienced teachers

35 72.9 0 0

Professional development acitivities in the 12 months prior to

the survey did have a positive impact on teaching practice

33 68.8 0 0

Index of workplace well-being and stress 0 0.0 42 87.5

Fixed-term contract: less than or one school year 0 0.0 15 31.3

Index of professional collaboration 46 95.8 0 0

Index of target class autonomy 47 97.9 0 0

PhD students focuses on three areas: reproducible re-

search; multivariant analysis and SEM methodology;

triangulation (Panchenko et al., 2021). SEM method-

ology helps researcher determine the effectiveness of

educational innovations in different educational con-

texts, as well as model and study phenomena in their

interrelations; understand the influence of latent fac-

tors, develop systemic and critical thinking.

An important point in training specialists to use

SEM is to select or obtain the necessary data sets

that are representative and valid. For example, we of-

fer our students such data: All-Ukrainian survey data

from Ukrainian teachers. The main criteria for choos-

ing it are: 1) an array of data is freely accessible, 2) it

is large (contains 3600 lines), 3) it is accompanied

by supporting documentation, 4) the array and doc-

uments have Ukrainian and English versions, 5) the

array variables are simple and understandable, 6) it is

possible to conduct comparative studies with the data

of the International Talis Teacher’s Survey.

During the case study the teacher’s self-efficacy

model using SEM methodology were checked, the

obtained results were compared with the TALIS sur-

vey data (2013). The research demonstrated that self-

efficacy of Ukrainian teachers, especially in the stu-

dent engagement block, was lower.

Further development of work in this direction is

the creation of teaching and methodological support

for modeling by structural equations in the form of

a computer workshop in the AMOS and R environ-

ments for the training of researchers in the field of

pedagogy and social sciences and a proposal to in-

clude SEM in higher education research.

REFERENCES

Badri, M., Alnuaimi, A., Yang, G., Rashidi, A., and

Sumaiti, R. (2017). A Structural Equation Model of

Determinants of the Perceived Impact of Teachers’

Professional Development — The Abu Dhabi Appli-

cation. SAGE Open, 7(2).

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human

agency. American Psychologist, 37(2):122–147.

Chornyi, A. (2011). Modeliuvannia latentnykh zmin-

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

306

nykh: rozvytok, suchasnyi stan ta perspektyvy (Mod-

eling latent variables: development, current state and

prospects). Visnyk Kyivskoho nats. un-tu imeni Tarasa

Shevchenka. Ser. Ekonomika, 129:41–43.

Khine, M. S., editor (2013). Application of Structural Equa-

tion Modeling in Educational Research and Practice.

Sense Publishers.

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and Practice of Structural

Equation Modeling. The Guilford Press, New York,

4th edition.

Krasnoryadtseva, O. M., Kabrin, V. I., Muraveva, O. I.,

Podoynitsina, M. A., and Chuchalova, O. N. (2014).

Psihologicheskie praktiki diagnostiki i razvitiya samo-

effektivnosti studencheskoy molodezhi (Psychologi-

cal practices of diagnostics and development of self-

efficacy of student youth). Izdatelskiy dom TGU,

Tomsk.

Kremeshna, T. I. (2010). Pedahohichna samoefektyvnist:

shliakh do uspishnoho vykladannia (Pedagogical Self-

Efficiency: The Way to Successful Teaching). Uman.

Liu, Y., Bellibas, M. R., and Printy, S. (2018). How

school context and educator characteristics predict

distributed leadership: A hierarchical structural equa-

tion model with 2013 TALIS data. Educational Man-

agement Administration & Leadership, 46(3):401–

423.

Mitina, O. V. (2008). Modelirovanie latentnyih izmeneniy

c pomoschyu strukturnyih uravneniy (Modeling latent

changes using structural equations). Eksperimental-

naya psihologiya, 1:131–148.

Nasledov, A. D. (2013). IBM SPSS Statistics 20 i AMOS:

professionalnyiy statisticheskiy analiz dannyih (IBM

SPSS Statistics 20 and AMOS: Professional Statistical

Data Analysis). Piter, SPb.

OECD (2018). TALIS. http://www.oecd.org/education/

talis/.

Panchenko, L. F. (2013). Modeliuvannia strukturnymy

rivnianniamy yak instrument pedahohichnoho

doslidzhennia (Modeling by structural equations as

a tool for pedagogical research). Visn. Luhan. nats.

un-tu imeni Tarasa Shevchenka: Pedahohichni nauky,

18(277):108–114.

Panchenko, L. F., Korzhov, H. O., Kolomiiets, T. V., and

Yenin, M. N. (2021). PhD student training: principles

and implementation. Journal of Physics: Conference

Series, 1840(1):012056.

Panchenko, L. F. and Razoronova, M. V. (2016). Mod-

eliuvannia strukturnymy rivnianniamy yak skladnyk

pidhotovky doktoriv filosofii (Modeling by structural

equations as a component of preparation of doctors

of philosophy). Naukovyi Visnyk Donbasu, 1-2:108–

114. http://nvd.luguniv.edu.ua/archiv/2016/N1-2(33-

34)/5.PDF.

Plous, S. (2021). Ranking of U.S. Sociology Ph.D.

Programs. https://www.socialpsychology.org/gsociol.

htm.

Questionnaires (2017). Questionnaires (in ukr): TEACH-

ERS Questionnaire. https://drive.google.com/open?

id=1L6SHvqpMAGPzeLkp8Ksb9E-KXdnkd0sd.

Scherer, R., Jansen, M., Nilsen, T., Areepattamannil, S.,

and Marsh, H. W. (2016). The Quest for Compara-

bility: Studying the Invariance of the Teachers’ Sense

of Self-Efficacy (TSES) Measure across Countries.

PLOS ONE, 11(3).

Shchudlo, S., Zabolotna, O., and Lisova, T. (2018).

Ukrainian Teachers and the Learning Environment.

Results of All-Ukrainian Monitoring Survey of Sec-

ondary School Teachers and Principals (by the TALIS

methodology). Trek LTD, Drohobych.

TALIS (2017). Access the full survey by TALIS

methodology raw data (in SPSS): TEACH-

ERS DATA. https://drive.google.com/open?id=

1bzh6U7MnOaFSt 1CV1BsQndCuLX WpWt.

www.soc.iastate.edu (2021). Structural equation

models for social and behavioral research.

http://www.soc.iastate.edu/dpeters/pubs/soc613-

syllabus-SS16.pdf.

Structural Equation Modeling in Educational Research: A Case-study for PhD Training

307