Perception and Interpretation of Emoji in the Pedagogical Process:

Aposterior Features of Artificial Digital Language

Rusudan K. Makhachashvili

1 a

, Svetlana I. Kovpik

2 b

, Anna O. Bakhtina

1 c

,

Nataliia V. Morze

1 d

and Ekaterina O. Shmeltser

3 e

1

Borys Grinchenko Kyiv University, 18/2 Bulvarno-Kudryavska Str., Kyiv, 04053, Ukraine

2

Kryvyi Rih State Pedagogical University, 54 Gagarin Ave., Kryvyi Rih, 50086, Ukraine

3

State University of Economics and Technology, 5 Stepana Tilhy Str., Kryvyi Rih, 50006, Ukraine

Keywords:

Emoji, Artificial Languages, Digital Communication, Perception, Interpretation, Mental Frame, P-Semantics,

Sign.

Abstract:

This study is experimental. The investigation is based on data collected from an experiment that was con-

ducted involving participants in the educational process. The essence of the experiment is to test the artificial

digital language of emoji in the learning process from the standpoint of both teachers and students in the

field of education. But the experiment was augmented by representatives of other professions (programmers,

economists, artists, writers), which helped to expand the object of the study, extrapolating the findings of the

experiment on different areas of activity surveyed. The results were obtained for the following categories of

respondents: age, profession, knowledge of foreign languages. Experimental data helped revealed the follow-

ing issues: 1) artificial emoji language reproduces polylaterality in structure (elements of sign generation) and

semantics (multi-vector perception and interpretation of the sign). This explains the scale of differentiation of

emoji characters; 2) the polylateral perception and interpretation of emoji depends on the speaker, which in

study was classified according to the above categories. It was concluded that the perception and interpretation

of the emoji sign depends on all the highlighted categories with an advantage to the professional activity of

the speaker and their experience in a particular profession. The concept of a priori and a posteriori of arti-

ficial languages was also revealed for the purpose of the research. Language of emoji we categorize as an

apriori-posteriori since by form and meaning digital emoji signs display features of both types: the shape of

the components of the emoji sign refer to other semiotic systems (such as cuneiform or Morse code); in terms

of content, the emoji sign in digital communication can be interpreted depending on individual verbal skills,

which, in turn, was considered through the prism of frame semantics (P-semantics) of Charles Fillmore. The

experiment results demarcated perceptual characteristics and interpretation of digital emoji signs by respon-

dents depending on the nature of their professional activity. Thus, it was concluded that representatives of

the humanities and social sciences (both in service teachers and applicants for the pedagogical profession)

and representatives of sciences (economists, programmers) have antithetical properties of perception and in-

terpretation of emoji in digital communication. This coincides with the concept of mental frames embedded

in the thinking structure of each individual. The prospects of this research consist of bringing other edu-

cational professionals into the experiment, as well as non-teaching professionals to determine the deductive

hypothesis of the role, function and influence of digital language of emoji on teachers and non-teachers. The

latter will make it possible to identify the advantages and disadvantages of digitalization of society both in the

educational process and outside its framework.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4806-6434

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6455-5572

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3337-6648

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3477-9254

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6830-8747

1 INTRODUCTION

Modern specialists in the field of computational lin-

guistics (Anber and Jameel, 2020; Annamalai and

Abdul Salam, 2017; Brody and Caldwell, 2019;

Chich

´

on and Jim

´

enez, 2020; Schmidt et al., 2021),

Makhachashvili, R., Kovpik, S., Bakhtina, A., Morze, N. and Shmeltser, E.

Perception and Interpretation of Emoji in the Pedagogical Process: Aposterior Features of Artificial Digital Language.

DOI: 10.5220/0010929500003364

In Proceedings of the 1st Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology (AET 2020) - Volume 2, pages 141-155

ISBN: 978-989-758-558-6

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

141

test the idea that emoji is now a promising means

of pedagogical communication. Evans (Evans, 2015)

emphasizes that emoji have enormous potential in

transferring meaning of the phrase and its shades of

emotions (Piperski, 2020). In the conditions of mod-

ern globalization and digitization, which the philo-

logical sciences have not escaped, the use of visual

elements in messages has become the norm. The ap-

proach has changed to interpret many of the problems

of text linguistics. Recently, researchers have begun

to actively study ways of transmitting and perceiving

information using semiotically complex or creolized

text. By semiotically complicated text we mean a non-

linear (palindrome in form and perception) text, the

content of which can be transmitted by one or more

optical signs. This creation of the text refers us to

pictographic and hieroglyphic writing, which is char-

acterized by an emphasis on visual reading of the con-

tent.

However, it should be noted that the digitalization

of the traditional text with the help of ICT reveals

a new communicative barrier – the problem of sign

interpretation. In our article (Makhachashvili et al.,

2020) the technology of visualization of the text of

fiction (poetry) with the help of emoji symbols on the

Emoji-Maker platform was presented. During the re-

search we came to the conclusion that such an emoji

ICT experiment activates students’ thinking, develops

creative attention, gives an opportunity to concisely

reproduce the meanings of poetry (Makhachashvili

et al., 2020). However, at the same time, the above-

mentioned problem of sign interpretation was re-

vealed, since the mental frames of a person, which

depend directly on the genetic structure of thinking,

take part in the generation of an optical sign. This, in

turn, leads to the fact that not only the perception of

the sign will have differences, but also the basis of its

generation (geometric shape, color, emotion, associa-

tion). Makhachashvili and Bakhtina (Makhachashvili

and Bakhtina, 2019) consider this problem through

the prism of L. Wittgenstein’s hypothesis about indi-

vidual language (“Sprachspiel”): “Note that the hu-

man brain copies the structure of only one language

(genetic), despite the possession of two or more peo-

ple. foreign languages. Therefore, if the dialogue

takes place between people in one language, it does

not mean that they reflect the structure of the sym-

bolic system of dialogue. Genetically (mentally –

in L. Wittgenstein) they structure and, accordingly,

perceive and interpret the text differently. And this

distinction occurs due to the neural network formed

in the structure of genetic language in the human

brain” (Makhachashvili and Bakhtina, 2019).

Since this digital technology is of great interest in

the field of philological communication today, we be-

lieve that the further development of text visualiza-

tion technology will contribute to the effective study

of fiction by students of philology. However, in our

opinion, it is worth paying more attention to the prob-

lem of interpretation of the sign, because in the global

sense, the level of understanding between humanity

depends on it. Therefore, appealing in the article

(Makhachashvili et al., 2020) to the experiment with

students generating optical text on the material of fic-

tion (Fane, 2017), the team conducted another exper-

iment. Its purpose is identifying features of posteriori

construction of an artificial sign in digital communi-

cation, dependent on perception of both students and

teachers.

The objective of the paper. Systematic analysis of

the empirical method in the study of interpretation of

the optical emoji sign during its generation and per-

ception, which will trace the semiotic transformation

in the analysis of transgression of signs from natural

languages into digital artificial (a posteriori) ones, in

particular emoji. Determining the pedagogical per-

ception of the optical sign is made possible by the

fact that the experiment involved not only teachers

and students of philology, but also representatives of

various fields: historians, economists, programmers,

mathematicians and others, which allows to compare

perceptions and interpretations of artificial emoji.

First of all, let us define what is meant by

the aposteriori nature of artificial languages. We

use this definition through the work “Construction

of languages: from Esperanto to Dothraki” (Piper-

ski, 2020), in which the author explains the differ-

ence between a priori and a posteriori artificial lan-

guages: “Most early artificial languages were cre-

ated by philosophers and had an a priori nature; this

means that they were not based on existing languages,

but were created on arbitrary principles. . . Begin-

ning in the XIX century, artificial languages were

usually a posteriori, i.e. to some extent created in

existing languages. . . ” (Piperski, 2020). However,

note that we refer the emoji language to some ex-

tent to apriori-posteriori type because that language

is originated in the computer being (hereinafter –

CB) – a complex, multidimensional field of synthe-

sis of reality of human experience and activity medi-

ated by digital and information technologies; techno-

genic reality, a component of the technosphere of

existence (Makhachashvili, 2013). Thus, like a pri-

ori languages, emoji is classified as a logical lan-

guage (loglang) – a programming language. This

dual nature is prompted by the fact that emoji was

first created by a Japanese designer Shigetaka Kurita

(Negishi, 2014), who became the first 176 charac-

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

142

ters for Japanese users of the i-mode mobile platform.

The pictures he created (12x12 pixels) correlated with

the lives of the inhabitants of the city of the founder

(Gifu Prefecture, Japan), reproducing the most com-

mon discourses of real communication. Therefore,

taking as a basis the idea of manga – one of the forms

of Japanese art, Kurita reproduced pictographically

elements of Japanese culture, and the phonetic coin-

cidence of the word emoji is accidental. Already in

Unicode Consortsium emoji received the meaning of

emotional characteristics.

In our study (Makhachashvili et al., 2020) the

role of the reader-interpreter is emphasized, which al-

lowed us to conclude the following: recipient (reader-

interpreter), using specific technological tools, a vi-

sual iconic sign (smile) reproduces the polylateral

metalinguistic functionality of the meaning of the

sign on the basis of the artistic word (Makhachashvili

et al., 2020). The results, on the one hand, complicat-

ing the structure of semiotic field of artificial sign, on

the other hand – expanding mental frames of human

thought, explicates the emoji sign as universal rather

than local or mental (the latter, in turn, is confirmed

that, once adopted by the Unicode Consortsium,

emoji transgressed into the international language of

characters, the creation of which has become purely

digital). Versatility and digital conditionality of emoji

provides multi-vector semantic load of the sign. Ad-

dressing this issue, Makhachashvili and Bakhtina

(Makhachashvili and Bakhtina, 2019) introduced the

linguistic concept of “polylateralism” – (from the an-

cient Greek πoλ

´

υ – many; from the Latin latus – side)

– a category that reflects in the digital emoji sign ver-

satile, multi-vector reproduction of emotions through

logical-structural, lexical-grammatical, morphologi-

cal, etc. means (Makhachashvili and Bakhtina, 2019).

So, appealing to the logic (a priori) and a posteri-

ori of the artificial digital emoji language, and based

on research on this topic, we propose the rundown

of the pedagogical experiment. We aim to trace how

emoji is used in the learning process through digi-

tal communication, what criteria are used by educa-

tors and learners when constructing an artificial sign,

which plays a special role in the interpretation of a

particular emoji.

2 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

To solve the delineated tasks, the following meth-

ods were used: analytical review – for the study and

analysis of scientific and methodological literature,

curricula, generalization of information to determine

the theoretical and methodological foundations of the

study; pedagogical modeling – for the study of ped-

agogical objects through the modeling of procedural,

structural and substantive and conceptual characteris-

tics and individual “aspects” of the educational pro-

cess. Empirical method – in order to study the phe-

nomenon through experiment and rational process-

ing of the obtained data. Structural method – in or-

der to identify and analyze structural elements, indi-

vidual components, categories, etc., which form the

emoji-sign. The method of component analysis – in

order to identify the minimum semantic (semantic) el-

ements that form the semantic component of the sign.

Semiotic method – in order to study the sign from the

standpoint of its organization, the properties of its el-

ements and categories. Descriptive method – in order

to describe in detail, the language units in the inven-

tory and systematization. Dialectical method as a way

to find a theoretical construction of the linguistic pic-

ture of the world, the study of the true criteria for the

coexistence of language and the world, language and

man, language and machine. Logical-analytical meth-

ods, namely the method of induction and deduction,

which allows to consider the content of the object,

specifying and generalizing its concept; the method

of formalization as the study of an object by reflect-

ing their structure in symbolic form.

3 RESEARCH RESULTS

In order to identify differentiation in the interpreta-

tion of emoji, we conducted an experiment involving

110 respondents aged 10 to 70 years (figure 1). Such

a large-scale coverage of the age category allowed to

fundamentally reflect the picture of the world and dig-

ital literacy of mentally different representatives, and

also allowed to distinguish groups of people whose

linguistic pattern differs significantly from respon-

dents of other age categories. All this is directly re-

produced in the interpretation of the optical digital

sign. Thus, the results of the experiment show that

emoji is used more by respondents whose age range

is from 10 to 20 years, and to a lesser extent – from

40 years (figure 2). Accordingly, such results explain

the verbal skills of the recipients, depending on the

professional and mental qualities, which will be dis-

cussed later.

Since the experiment was conducted in order

to identify functioning of digital emoji language in

the pedagogical process, divided into various narrow

fields, the part was taken by representatives of the fol-

lowing professions: philology (educators (lecturers,

teachers) and students). However, the validity of the

experimental field increases due to the participation

Perception and Interpretation of Emoji in the Pedagogical Process: Aposterior Features of Artificial Digital Language

143

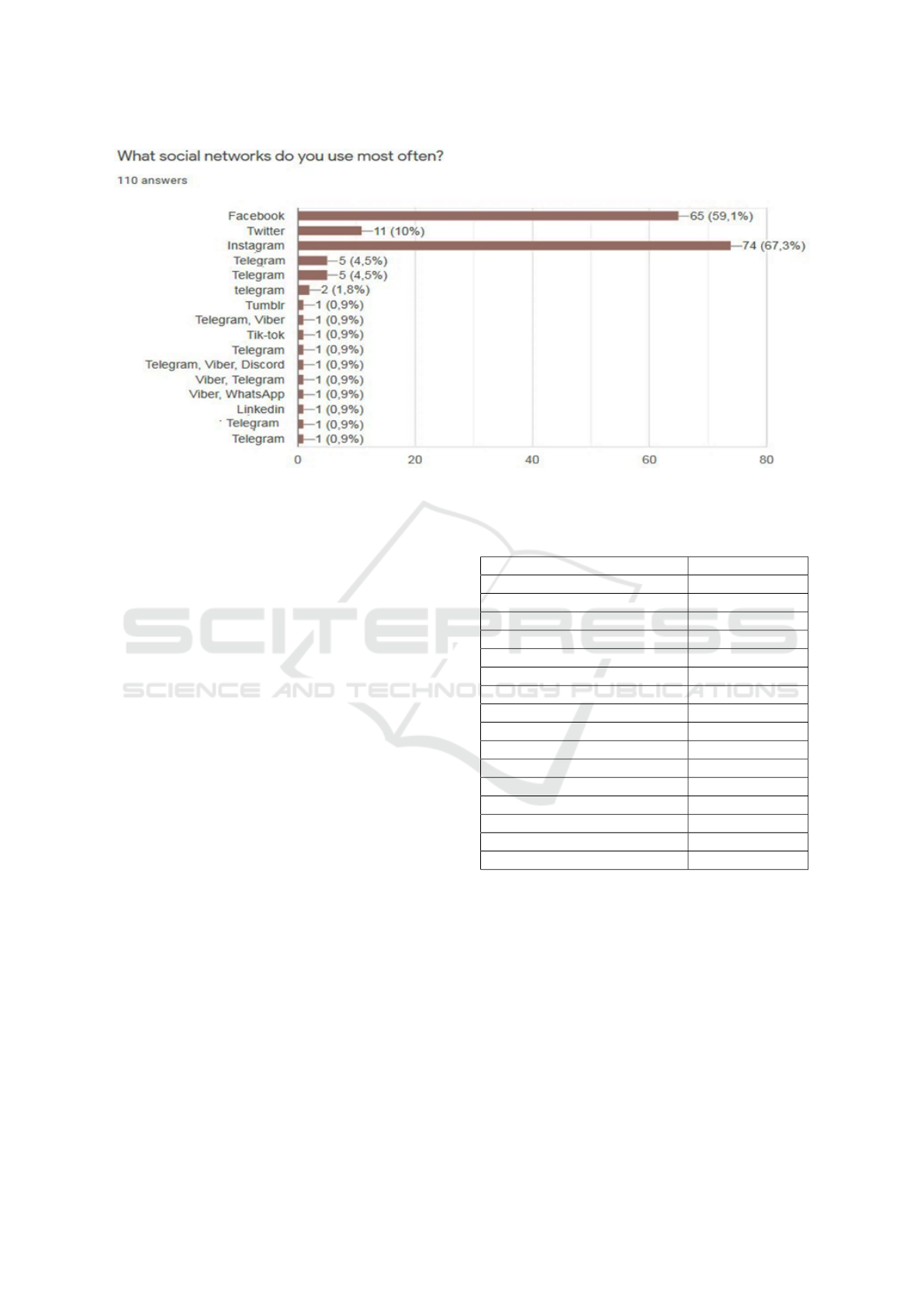

Figure 1: Frequency of emoji usage in digital communication.

Figure 2: Age brackets for emoji users in digital communication.

in the experiment of representatives of the follow-

ing fields: history, IT, mathematical modeling, pub-

lishing, choreography, psychology, economics, diplo-

macy, archeology, IT, fine arts. The status of the

respondent varies from student to habilitated doctor.

The wide scale of profile differentiation fractalizes se-

mantic shifts in the interpretation of a sign in more de-

tail. This is characterized, in addition, by the choice

of social network, where the respondent uses emoji

(figure 3). We can see that most age groups of re-

cipients use Facebook, Instagram, Twitter. However,

the age group of up to 20 years tests artificial lan-

guages on other platforms (Tik-Tok, Discord, Tum-

blr), which is also reflected in the verbal skills of the

recipients. In terms of professional affiliation, Face-

book is more used by the teaching staff of various uni-

versities (59.1% of respondents); Instagram – by stu-

dents of different universities – 67.3%, other social

networks – by the lowest percentage of respondents,

which is fractalized to all categories of respondents.

Another important characteristic of differentiation

and fractalization of answers is mastery of foreign

languages. Among the respondents were experts in

the following languages: Russian (99%), English

(98%), Spanish (74%), Italian (49%), French (49%),

German (23%), Chinese (4%), Japanese (2%), Korean

(1%), Czech (1%), Polish (1%), Georgian (1%), Ar-

menian (1%), Hebrew (1%), Turkish (1%). There-

fore, the results concluded that the use of emoji in

digital communication (both in everyday life and in

the professional sphere) is more pertinent to recipients

with knowledge of two or more foreign languages

(table 1). However, the interpretation of a particu-

lar sign varies and depends on a particular foreign

language (and / or on professional skills). Emoji is

a typical visual complement to the content of text /

speech in digital communication for experts in Orien-

tal languages, including Mandarin Chinese, Japanese

and Korean, which, in turn, refers us to the mental

frames of Oriental language structures. Fillmore (Fill-

more, 1985) classifies frames as P-semantics, which

operates with the concept of interpretive description

of the semantics of tokens, grammatical categories

and text. Such semantics includes three components:

compositional semantics (frame structure of the text),

practical reasoning based on the use of frame knowl-

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

144

Figure 3: Choice of social network, where the respondent uses emoji.

edge (knowledge of reality) and provides identifica-

tion of implicit semantic connections between utter-

ances in the text; reasoning based on knowledge of

communicative intentions represented in frame form.

In the situation of reasoning, natural-linguistic infer-

ence is considered as a set of operations on the el-

ements of frames (Fillmore, 1985). Reliance on the

frame structure also applies to experts in the Span-

ish language (74%). However, it’s worth noting that

in Hispanic communication emoji has emotional pre-

supposition: Spanish language professionals a pri-

ori interpreted emoji of a psycho-emotional meaning,

mostly adiaphorizing rational structure components

of the sign. The positive attitude and use of emoji

is also observed in the professional specifics, in par-

ticular, artists who, unlike experts in Romance lan-

guages, appeal to real causal (implicit and semantic)

connections both between utterances in digital com-

munication (emoji) and between components of one

sign.

The most unexpected among the results of the

survey were the responses of computer science spe-

cialists, whose attitude to emoji was twofold. How-

ever, we can assume that experts in the field of IT

completely include emoji in the loglan, which apriori

cannot have an emotional substrate. Computer sci-

ence specialists, in turn, perceive not so much a lan-

guage as its matrix. Under such conditions, the log-

ical indicator is that the most extensive use of emoji

is in the humanities (philologists, historians, philoso-

phers), the specifics of whose profession refers to in-

formation as a tool of influence, which is directly in-

ferred from the emotional substrate. To a lesser ex-

tent, emoji is used by the exact sciences specialists,

Table 1: Distribution of native languages spoken by emoji

users.

What languages do you speak? % of respondents

Ukrainian 100%

Russian 99%

English 98%

Spanish 74%

Italian 49%

French 49%

German 23%

Chinese 4%

Japanese 2%

Korean 1%

Czech 1%

Polish 1%

Georgian 1%

Armenian 1%

Hebrew 1%

Turkish 1%

the results of whose activity are represented by nu-

merical data. The smallest percentage – computer

science specialists, where the result is a matrix. The

same effectiveness, as in the above case, applied to

the interpretation of the concept of emoji (table 2).

Artists and / or Oriental and Romance languages pro-

fessionals emphasized the iconicity / ideography of

the sign in digital communication, the graphic visual-

ization of which is independent of the narrative form,

but performs the contractual function of an auxiliary

non-verbal explicant. Specialists in the humanities

focused on the emotional characteristics of the sign,

which is designed to enhance the effect of the com-

Perception and Interpretation of Emoji in the Pedagogical Process: Aposterior Features of Artificial Digital Language

145

municative act in digital medium.

We mentioned above the verbal skills of the recipi-

ents, which, like the previous features, depend on age,

professional activity and knowledge of foreign lan-

guages. In order to trace the differentiation of the per-

ception and interpretation of the emoji sign, 10 most

used emoji in different operation systems and digital

platforms were added to the survey in order to trace

how the respondent understood each sign. In addition

to the characteristic of popularity, the dual or poly-

lateral nature of the sign was an important factor in

choosing emoji for the experiment, which hypotheti-

cally refers to the conclusion about the differentiation

of the perception of signs by each recipient. Thus,

the sign #1 (figure 4) for 99% of respondents is in-

terpreted unambiguously, with deviations of the se-

mantic load in 1%: ok, good, cool, great, well done,

good job, very good, super, perfectly etc. However,

from recipients aged 10 to 20 we have answers that

reflect age-related deviations in perception, for exam-

ple, “I like it (smiley is not very much, my grand-

mother throws me and teenagers use for this )”

Figure 4: Emoji sign #1.

A similar perception applies to the sign #2 (fig-

ure 5), the interpretation of which is 100% syn-

thesized with a negative connotation and explicated

within one semantic field. However, given the scale

to differentiate the characteristics of respondents, the

verbal definitions of the sign can be traced to the

structure of the linguistic ousia of answers, hypothet-

ically deducing the nature of the category / profession

/ status / experience of a particular answer (table 3).

Figure 5: Emoji sign #2.

The sign #3 (figure 6) in digital communication

embodies the polylateral structure of perception and

interpretation. The answers to this sign are radically

different (table 4).

Figure 6: Emoji sign #3.

Perception and interpretation of the sign varies

within the concepts of “horror”, “shock”, “fear”, “sur-

prise”. Accordingly, it will be appropriate to empha-

size the characteristics of the recipient to trace the

frame structure of speech and verbal skills of respon-

dents. Thus, the sign #3 is interpreted and perceived

as horror in the category of 20 to 40 years (60%),

shock – from 10 to 20 years (15.5%), fear – from 40

to 65 years (22.7%), as well as 66 years (1%) and 70

years (1%), surprise – from 40 to 65 years (22.7%).

According to professional characteristics, the answers

are fractalized into all categories evenly.

The situation with the sign #4 is more unambigu-

ous (figure 7). However, it should be noted that

the age categories 10 to 20 and 20 to 40 years in

most cases interpreted the sign in terms of CB exclu-

sively, emphasizing the digital continuum, in contrast

to other categories that described the sign purely emo-

tionally in the real ontological dimension (table 5).

Figure 7: Emoji sign #4.

The sign #5 (figure 8) expresses an error in inter-

pretation and perception of 2%. Among the most typ-

ical – “sadness”, “tears”, “sadness”, “fiasco”, “pain”.

The sarcastic connotation of the use of the sign in dig-

ital communication (age category from 40 to 65 in the

humanities) (table 6) has to be emphasized, as well

as despair, depression, fatigue (age category 10 to 20

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

146

Table 2: Interpretation of the concept of emoji by respondents.

How do you understand what emoji is?

Emoticons Facial expressions in social networks

Emoticons A kind of graphic language

Emoticon Mood display

Smileys Face sticker to emphasize or express your emotions in the message

Expressing emotions with pictures The language of various graphic signs

Small pictures used to indicate emo-

tions

A picture that reproduces feelings, understandable to both the recip-

ient and the author of the statement

Signs A graphic sign, an illustration that conveys a certain concept, is used

when communicating online

A symbol for conveying the emotional

side of communication

Psychological state that reflects the instantaneous reaction to exter-

nal factors

Graphic symbol for emotions and states Coloring of the written text and accessible expression of emotions

A picture depicting a certain emotion Emotions that help to convey more clearly our emotions, state, atti-

tude to the situation, feelings, and sometimes due to emotions you

cannot even write a text.

Emoticons designed to facilitate com-

munication and convey different states

/ emotions

Mini drawings to indicate emotions, objects through which it is pos-

sible to convey information

Expression of emotions with the help of

visual images

Use of digital symbols to demonstrate emotions, feelings, personal

reaction to messages, photos in online communication

A picture that helps you show your own

emotions in text messages

Auxiliary ideographic record

Table 3: Generalized definitions of Emoji sign #2.

What does the following emoji mean to you? In what context could you use it?

Surprise Means surprise, used as a reaction to a message, be

it a photo, video or news

Shock When I realized that 1 course had already ended

Oh really! You can go crazy, but really

Wow Surprise. Hidden irony (rare)

To indicate surprise / astonishment, but mostly with a

positive connotation

Incredible!

Surprise, admiration Surprise from the written (description of actions in

the message)

Horror! Shock! What is happening! Surprise from the situation or from the words spo-

ken

Table 4: Generalized definitions of Emoji sign #3.

What does the following emoji mean to you? In what context could you use it?

What a horror! Omg! Strong surprise with hints of feelings for the

interlocutor

Stupefaction Horror; surprise in a negative context

Cannot be Madre mia! in a bad way

“Horror” – wrote a work on one topic, and it was nec-

essary on another))

Drip! It is too much! I’m shocked!

Horror! / Reaction to something very unpleasant Oh my God!

To indicate surprise / shock, but not only with a positive

connotation. Sometimes as a synonym for the expression

“Oh, only!”

Reaction to unexpected news, surprise

Oh no! What? Something fascinating

People are good, the house is white Surprise. Negative or jokingly negative context.

Perception and Interpretation of Emoji in the Pedagogical Process: Aposterior Features of Artificial Digital Language

147

Table 5: Generalized definitions of Emoji sign #4.

What does the following emoji mean to you? In what context could you use it?

Love I really like it, I support it very much, thank you

very much

I like something I like you

I love you! Support, admiration

Wonderful “Magical!” (positive warm attitude, especially to

something sweet, sweet)

“With love” – especially a warm relationship, thank you What I see is beautiful

Fascination with news / comments from a close person /

child / friend

When I saw the puppy

See something cute, beautiful Friendship compassion

Fascination with news / comments from a close person /

child / friend

It has many meanings: it conveys pleasant amaze-

ment, joy, admiration for beauty, love

years – students) – with appropriate explanation by

the recipients of their interpretation and perception:

term finals at the university).

Figure 8: Emoji sign #5.

The sign #6 (figure 9) is identically interpreted and

perceived by the respondents, but there is a differen-

tiation in the verbal reproduction of the sign. Thus,

respondents with an age category ranging from 10 to

20 years, as well as specialists in Germanic languages

have the signification “kiss”; from 20 to 40 years (re-

spondents of the humanities) – “flirtation”, “love”,

and respondents of exact sciences – “Air kiss”, “I kiss

and love”. “You are very dear to me”. Respondents

between the ages of 40 and 65 provide a more detailed

lexical field, giving the signifier an explicit character:

“You are my good, thank you. A sign of support, grat-

itude, approval, support”. The results showed that

such an explication would be more typical for teach-

ers with sufficient experience in educational institu-

tions, mainly in the humanities. It is noteworthy that

IT professionals do not visually perceive the sign for

two reasons: 1) this symbol can be used only with the

close social circle; 2) visually do not like the symbol.

This perception once again concludes the structure of

thinking of specialists in the exact sciences, the result

of which is a number / calculation / matrix.

An ambiguous picture is observed with the sign #7

Figure 9: Emoji sign #6.

in digital communication (figure 10), because accord-

ing to previous experimental empirical data, it was

stated that the sign has a latent negative connotation.

In order to confirm or refute the station, the mentioned

sign was placed in the questionnaire. The results

showed a proportion of 60/40: 60% of respondents,

whose age category is mainly from 20 to 40 (23%)

and from 40 to 65 (37%), perceive and interpret the

sign, emphasizing the neutral and / or positive con-

notation that explains approval of something (“okay”,

“good”, “super”, “yes” etc.). However, 40% of re-

spondents (mostly humanities students – age group

10 to 20 years, as well as representatives of creative

professions – artists, writers) see in the sign a negative

connotation, which is characterized by several expres-

sions: either sarcasm, or contempt for the interlocutor,

or attempt to maintain one’s opinion (table 7).

It was experimentally interesting for the authors

of the study to trace the emotional characteristics of

the sign #8 (figure 11).

Undoubtedly, the sign is an identifier of the global

civilizational phenomenon of modernity, which led to

the global pandemic – the coronavirus in COVID-19.

Specified sign, in fact, with appeared in digital com-

munication usage at the beginning of the quarantine,

which covered virtually the whole world. However,

computer being eliminates any locality, leaving in the

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

148

Table 6: Generalized definitions of Emoji sign #5.

What does the following emoji mean to you? In what context could you use it?

I’m crying When I want to emphasize my fatigue from some-

thing, irritation, helplessness

Very sad Difficult situation

Sadness / crying Sorry, pain, injustice

Tears, sadness, can be sarcastic Notification of bad news, reaction to something sad

“Sorry” – disappointment, sadness I forgot to attach the file to work

Disappointment when something failed, but this smiley

still has a humorous connotation. In my opinion, it can-

not be used as a reaction to the news related to the dete-

rioration of human health, or, God forbid, death.

Something tragic

frustration in life “but not what the stars are so united, I will not give

up” + hyperbolization of real disappointment

frustration in life When something is difficult / impossible to change,

but I would like to.

sadness or tears with irony / sarcasm (any context) Personal correspondence or friendly, reaction to

the message

Table 7: Generalized definitions of Emoji sign #7.

What does the following emoji mean to you? In what context could you use it?

Like Keep it up, super

Super Short answer to the sign of approval, support, ac-

ceptance of information

OK Very good, or sarcastic

“good idea” “approval” (neutral)

Well done! – approval Means that the above seen cool (accompanied by

other emojis can mean causticity, on the bag, gen-

erally expressing both good and evil)

Well done / class! / Great job! / OK Approval of user message (actions described in

message)

Class, great, thanks! All is well! Most likely, it is a re-

sponse / reaction to someone’s fulfilled request or reac-

tion to the news and carries approval, or sometimes this

smiley is a neutral response.

Again, it can mean either satisfaction and approval,

or I use it in an ironic sense

postironia good job; consent

Figure 10: Emoji sign #7.

substrate a psycho-emotional factor of sign percep-

tion. Thus, according to the results, we obtained the

following disclosure: 70% of respondents of all cat-

egories explained the sign as “disease”, “epidemic”,

“temperature”. However, the answers of humanities

Figure 11: Emoji sign #8.

teachers, as well as students aged 20 to 40, were typ-

ical. The signifier of the #8 sign of the mentioned re-

spondents is “silence” or “I do not use”. Representa-

tives of exact and natural sciences mostly emphasized

that the sign does not belong to their digital contin-

Perception and Interpretation of Emoji in the Pedagogical Process: Aposterior Features of Artificial Digital Language

149

uum (table 8).

The sign #9 (figure 12) is not characterized by

popularity in use in computer being, therefore a priori

it was placed for the purpose of revealing of differ-

entiation of a lexical field of respondents that is pro-

jected on perceptual sensations.

Figure 12: Emoji sign #9.

A remarkable point is that the less popular (almost

unknown emoji sign) was 100% interpreted unam-

biguously and with one (in this case – negative) con-

notation. This is important information, because pop-

ular characters have many semantic branches in recip-

ients of different categories, which again confirms the

open aposteriority of artificial emoji language with

the emergence of new connotations in digital com-

munication and expansion of the lexical field of the

respondent (table 9).

The sign #10 (figure 13) in our experiment is the

key optical sign in digital communication.

Figure 13: Emoji sign #10.

The sign is quite popular, however, as the results

of the experiment showed, it is popular not for the

denotation, but for the psycho-emotional characteris-

tics of the respondent. 99% of respondents answered

that the sign has a negative connotation and optically

reflects the state of anger, rage and rage. In fact, this

sign is mental in location – a sign of Japanese origin to

express a sense of triumph (in Unicode Consortium –

“Face with Look of Triumph”). Thus, we conclude

that the mentioned mental frame was not read by com-

puter science specialists, artists or connoisseurs of

oriental languages. The sign was interpreted and per-

ceived according to the universal psycho-emotional

state – the state of anger, rage, anger (table 10).

The respondent who provided the only correct an-

swer is a historian by profession. Hypothetically and

deductively, we can conclude that in this case the

emotional nature of the artificial language emoji pre-

vailed, which, in fact, is one hundred percent embed-

ded in the concept of Unicode Consortium. Correct

disambiguation of this sign is an exception to appeal

to the respondent’s profession when it comes to text

as information. For linguists the text was perceived

as a structure for computer science specialists – a ma-

trix, representatives of the exact sciences – hypothe-

sis. Perceiving the text as information, the represen-

tative of the historical profession did not notice the

emotional nature of the sign, relying in general on the

information about this sign, which is its (sign) English

name “Face with Look of Triumph”.

The final stage of the survey was the question

“Can emoji replace natural language?”. In fact, the

last question is an additional result of previous con-

clusions on the use of emoji in the pedagogical pro-

cess, depending on the different categories of respon-

dents. The results of the survey show the following

picture: 5.5% (6 respondents) answered “Yes, in full”;

29.1% (32 respondents) – “50/50”; 59.1% (65 respon-

dents) – “No, they can’t” (figure 14).

Note that the answer “Yes, in full” belongs to the

respondents, whose age category is mostly from 10

to 20 years, to a lesser extent – from 20 to 40 (stu-

dents and teachers of philology and artists). In the

first case, such results are explained by the nature of

the humanities (mostly literary studies), where emoji

is an a priori fact of the aposteriori continuum (for

example, a work of fiction), and therefore is one hun-

dred percent significant and signifier at the same time.

In the second case, the object of fine art is essentially

synonymous with emoji pictographic (visual, optical)

result of creative activity.

The answer “50/50” belongs to philologists (lin-

guistics), as well as representatives of sciences

(economists), social sciences (psychologists), hu-

manities (archaeologists, publishers). Philologists-

linguists appeal to the nature of their profession, con-

sidering the text (including art) as a structure – in par-

ticular in syntagmatics and paradigmatics, and thus,

this explains the interest in the differential verbal-

ization of the polylateral emoji sign as an apriori-

posteriori system of thinking (Makhachashvili and

Bakhtina, 2019). Hypothetically, we explain the po-

sition of the representatives of economic sciences,

appealing to the ergonomic ousia of language and

speech resources in digital communication. In the

case of the social sciences and humanities, a funda-

mental factor is the understanding of emoji as a sup-

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

150

Table 8: Generalized definitions of Emoji sign #8.

What does the following emoji mean to you? In what context could you use it?

Quarantine Warning or description of the current situation

I’m sick I’m in a mask)))

I do not use Mask on the face, silence

Coronavirus Wearing a mask is mandatory, something related to

the hospital

Laughter under a mask COVID-19

I’m sick. But I would call such an emoji would not use Self-isolation

I’m silent Limitations of opportunities

I’m silent I’m sick or I’d better keep quiet

She fell ill. But in the conditions of quarantine - obser-

vance of safety rules.

Someone is sick and has to SIT AT HOME. (obvi-

ous influence of recent events)

Keep your distance I would have written earlier: I can’t speak! now it

is possible: we adhere to a mask mode. Didn’t use

this emoji.

Safety measures during the epidemic I do not use this, but now it is relevant, fashionable

to use as a reminder of protection

Table 9: Generalized definitions of Emoji sign #9.

What does the following emoji mean to you? In what context could you use it?

Head turn In alcohol intoxication

tired, broken, confused This is my face every morning

Amazingly I do not use it because it is disgusting

incomprehension An unusual, extraordinary situation; uncertainty

“Hangover” / “sleep deprivation” – a reaction to ques-

tions about the condition

Expresses stupidity, play, intoxication

Fatigue, inability to concentrate Confused

condition of students after the session Crazy situation

I don’t even know. when I swelled dumplings... I have never seen such a thing, he is a bit drunk

Table 10: Generalized definitions of Emoji sign #10.

What does the following emoji mean to you? In what context could you use it?

Malice Lots of work, boring, maybe annoying

Malice “evil”, “dissatisfied”, “not in humor”, “offended”

I’m angry I’m outraged

Fatigue I would kill!

Very emotional Horror

I’m boiling the last stage before anger, I can barely restrain my-

self from breaking

Anger, resentment, but again, I would use it to denote my

reactions in not very serious situations. In addition, I

read that this smiley is not an expression of dissatisfac-

tion, but has a different connotation, but for me it is an

expression of these emotions.

“God forbid she’s still something” XD (stock up on

patience)

Dissatisfaction, anger, the tram was late overflowing with negative emotions, I want to let

off steam

plement to the basic layer of information in digital

communication.

The answer “No, they can’t” belongs more to the

humanities, in particular to philologists, whose age

category is from 40 to 60, as well as 66 years. This

is probably explained by the temporal limits of the

emergence of the digital continuum in the former So-

viet republics, which in the long run prolonged the

universality, ideality and completeness of natural lan-

guages.

Perception and Interpretation of Emoji in the Pedagogical Process: Aposterior Features of Artificial Digital Language

151

Figure 14: Interchangeability of emoji sign system and natural language.

A big surprise was the position of computer sci-

ence specialists, which expresses the impossibility of

artificial languages (including emoji) to be a substi-

tute for natural. We have already emphasized this un-

expectedness above. Thus, we finally conclude that

computer science specialists, studying language as a

digital palindrome and an atemporal matrix, classify

emoji as a loglan, which a priori cannot have an emo-

tional substrate. 7 out of 110 respondents expressed

a desire to express their opinion on the question “Can

emoji replace natural language?”:

1. They can only supplement / diversify.

2. Replace no, but they give the correspondence cool

emotions. One emoji can convey your mood.

3. It is only a supplement to the written conversation,

although it can be a substitute for emotions in the

same conversation.

4. For me, emoji is more of a complement to ordinary

language, but not a replacement for it. It’s like a

picture book. Without pictures it is not so colorful

and fun.

5. They create an analog language, but natural lan-

guage is better, because you can operate live with

a newly created expression of emotions. Emoji

create boundaries within which you can express

yourself, but it is often impossible to find an exact

match for your emotions.

6. Partly, but it is worth the vicinity ’ favorites, each

emoji treated every person differently. And this

can lead to misunderstandings. And natural lan-

guage cannot be completely replaced, it is rather

a supplement to the expression of emotions.

7. To some extent. But some have already replaced

The respondents’ detailed answers were subject

to digital content analysis via an open source Voyant

corpus/text mining toolkit (https://voyant-tools.org/).

Two instruments were used specifitaly for 1) key

words identification (quantitavely calibrated word cir-

rus, featuring foregrounded concepts and notions) –

figure 15, and 2) key words frequency estimation (key

words trending in the horizontally segmented corpus

of responses) – figure 16. The key words of the

respondents’ detailed answers in equal proportions

are ”language”, ”emotions”, ”emoji”, ”expression”,

which hypothetically appeals to the conceptualiaza-

tion of natural languages as perfect, and therefore ar-

tificial languages, in particular emoji, are an optical

supplement to the expression of a particular context.

Consequently, emoji becomes not so much an artifi-

cial language as a form of language, a frame of writ-

ing that enhances and / or explains human feelings

and emotions, but at the same time can create misun-

derstandings of the explication of the signifier, which

depends on many factors: conditions, modality of ex-

pression etc.

Figure 15: Digital content analysis: calibrated word cirrus.

All the stated above, given the specifics of the re-

spondents’ answers, allows to conclude that in terms

of expression emoji is not an independent language.

Despite a clear and logical algorithm for generating

and codifying artificial language in computer being,

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

152

Figure 16: Digital content analysis: key words frequency.

the perception and interpretation of a particular emoji

sign varies depending on its use by a particular per-

son. However, it is this feature of the emoji language

that involves updating the content and form of aca-

demic writing in the pedagogical educational process

with the involvement of the ICT generated and imple-

mented emoji language in a specific context. After

all, the use of graphic signs will promote the devel-

opment of visual (photographic) memory in students,

as well as the development of emotional intelligence

(EQ), necessary for awareness and understanding of

one’s own emotions and the emotions of others. Ac-

cording to theory of Bar-On (Bar-On, 2010), emo-

tional intelligence is defined as a set of various abili-

ties that provide the ability to act successfully in any

situation (Goleman, 2005). In addition, under lock-

down through COVID-19 timespan, the use of emoji

in the pedagogical process can prevent stressful situa-

tions, and therefore provide for better and more effec-

tive learning, because emotional intelligence involves

the activation of the following functions: interpretive,

regulatory, adaptive, stress-protective, activational.

Thus, summarizing all the empirical data collected

through the survey, we can trace the effectiveness

of the use of artificial languages in the pedagogical

process, taking into account the specifics of the pro-

fessional activities of the respondent. However, we

should note that, summarizing the experimental data,

we get another question: why use the emoji language

in the pedagogical process? As the survey showed,

emoji are an integral part of modern digital commu-

nications. Moreover, the digitalization of the educa-

tional process by its nature appeals to the codification

of the semantic field of the communicative act. There-

fore, we consider emoji not so much a new as a newer,

modernized format of the sign system, which allows

different systems in its structure (cuneiform – hiero-

glyphics – Morse code) in digital communication.

4 CONCLUSIONS AND

PROSPECTS OF FURTHER

RESEARCH

Through an experiment, which consisted of surveying

participants in the educational process, we concluded

the following:

1. Artificial digital emoji language reproduces poly-

laterality in structure (elements of sign genera-

tion) and semantics (multi-vector perception and

interpretation of the sign). This explains the scale

of differentiation of emoji signs, taking into ac-

count mental frames and universal characteristics

at the same time.

2. The polylateral perception and interpretation of

emoji depends on the speaker, which the team of

authors classified in the study into the following

categories:

• Age

• Profession

• Knowledge of foreign languages

• Choice of social networks.

First of all, our empirical experiment was created

for teachers and educators in the pedagogical field.

This would allow us to trace the speed and direction

of the process of introduction of the digital continuum

into the pedagogical activity (artificial languages, in

particular emoji) in order to identify the feasibility

and effectiveness of learning at the intersection of nat-

ural and artificial languages and digital communica-

tion. However, representatives of other professions

Perception and Interpretation of Emoji in the Pedagogical Process: Aposterior Features of Artificial Digital Language

153

also joined the experiment: computer science spe-

cialists, economists, artists, poets and prose writers,

which gave us the opportunity to expand the subject

of our study, appealing not only to antithetical profes-

sions (humanities and sciences), but also to the nature

and specifics of each profession. The latter, in turn,

is encoded in the structure of the speaker thought by

mental frames that professional experience generates

a verbal language system and speaking respondents

and ideographic optical pattern embedded in the arti-

ficial language of books existence – language emoji.

According to the results of the experiment, we

also conclude that 100% of respondents (110 peo-

ple) use emoji both in everyday life and in profes-

sional activities. Although, the ousia of emoji in digi-

tal communication has significant shades of meaning

for each profession (not excluding age and language

skills). Thus, the representatives of the humanities

and social sciences when using emoji appeal to the

psycho-emotional load of the sign, considering it as

a supplement to the text in order to express emotions

in digital communication. Therefore, emoji for these

representatives can replace natural language for the

most part by 50%, as evidenced by the experiment to

reproduce the content of poetry on the basis of Emoji-

Maker platform (Makhachashvili et al., 2020).

Only a small percentage of respondents are con-

vinced of the equivalent replacement of natural lan-

guage with artificial. Such respondents include

philologists and linguists. However, it should be em-

phasized that it was linguists who provided detailed

answers regarding the perception and interpretation of

emoji signs, which confirms the vision of the emoji

language as an a priori-a posteriori system. Conse-

quently, emoji can be both a supplement to the main

text and an independent language with a full repro-

duction of meaning.

Representatives of sciences (mathematicians,

economists, programmers) consider emoji as an in-

dependent language to the least extent, the explica-

tion of which is the frame P-semantics of the thinking

structure of the representatives of the specified profes-

sions, which is as follows. For the outlined speakers,

the auxiliary element of the effectiveness of their pro-

fessional activity is the natural language itself, which

a priori puts artificial languages in the position of aux-

iliary symbols to obtain the result of work in the form

of digital content and matrix grid. Therefore, most of

the exact sciences use emoji, without giving clear and

unambiguous connotations to the sign during digital

communication.

In further research it is necessary to expand the

classification of respondents by professional activity

even more, involving the following representatives in

the experiment:

1. Teachers: specialists in physics, biology, law, po-

litical science and others who were not involved

in the experiment.

2. Non-teachers: other professions that are not re-

lated to educational and pedagogical activities.

Such scale and heterogeneity of respondents will

allow to outline Gaussian with normal (statistical) dis-

tribution of emoji language ousia, fractalizing the ef-

fect of the exponential function of artificial language

onto a quadratic function. Thus, we will have a de-

ductive hypothesis of the role, function and impact of

emoji language on teachers and non-teachers, which

will trace the advantages and disadvantages of digi-

talization of society both in the educational process

and outside its framework. In addition, this approach

appeals to the selection of the third subject of study

– the linguistic construction of individual “Sprach-

spiel” (term by Wittgenstein (Wittgenstein, 2007)) us-

ing natural and artificial languages with an empha-

sis on the apriori-posteriori nature of emoji in digital

communication.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research was performed within the framework

project of the Department of Romance Philology and

Typology (Borys Grinchenko Kyiv University, Kyiv)

“Development of European languages and literatures

in the context of intercultural communication” (regis-

tration code 0116U00660) and the framework project

of the Department of Ukrainian and World Liter-

atures. Kryvyi Rih State Pedagogical University,

Kryvyi Rih) “Poetics of the text of a work of art”.

REFERENCES

Anber, M. M. and Jameel, A. S. (2020). Measuring Univer-

sity of Anbar EFL Students’ awareness of emoji faces

in WhatsApp and their implementations. Dirasat: Hu-

man and Social Sciences, 47(2):582–593.

Annamalai, S. and Abdul Salam, S. N. (2017). Undergradu-

ates’ interpretation on WhatsApp smiley emoji. Jurnal

Komunikasi: Malaysian Journal of Communication,

33(4):89–103.

Bar-On, R. (2010). Emotional intelligence: An integral part

of positive psychology. South African Journal of Psy-

chology, 40(1):54–62.

Brody, N. and Caldwell, L. (2019). Cues filtered in, cues

filtered out, cues cute, and cues grotesque: Teaching

mediated communication with emoji Pictionary. Com-

munication Teacher, 33(2):127–131.

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

154

Chich

´

on, J. L. E. and Jim

´

enez, M. O. (2020). Assessment of

the possibilities of writing skills development in En-

glish as a foreign language through the application of

emoji as conceptual elements. Texto Livre, 13(1):96–

119.

Evans, V. (2015). We communicate with emo-

jis because they can be better than words.

https://qz.com/556071/we-communicate-with-

emojis-because-they-can-be-better-than-words/.

Fane, J. (2017). Why i use emoji in research and teach-

ing. https://theconversation.com/why-i-use-emoji-in-

research-and-teaching-75399.

Fillmore, C. J. (1985). Frames and the semantics of under-

standing. Quaderni di semantica, 6(2):222–254. http:

//www.icsi.berkeley.edu/pubs/ai/framesand85.pdf.

Goleman, D. (2005). Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can

Matter More Than IQ. Bantam, New York.

Makhachashvili, R. K. (2013). Dynamics of English-

language innovative logosphere of computer exis-

tence. Dissertation of Dr. Philol., Odessa I. I. Mech-

nikov National University, Odessa.

Makhachashvili, R. K. and Bakhtina, A. O. (2019). Empiri-

cal method in the study of polylaterality of emoji. Sci-

entific Bulletin of the International Humanities Uni-

versity, 4:141–144.

Makhachashvili, R. K., Kovpik, S. I., Bakhtina, A. O., and

Shmeltser, E. O. (2020). Technology of poetry presen-

tation via Emoji Maker platform: Pedagogical func-

tion of graphic mimesis. CEUR Workshop Proceed-

ings, 2643:264–280.

Negishi, M. (2014). Meet Shigetaka Kurita, the

Father of Emoji. https://www.wsj.com/articles/

BL-JRTB-16473.

Piperski, A. (2020). Construction of languages: From

Esperanto to Lekh Dothraki. Alpina non-fiction,

Moscow.

Schmidt, M., de Rose, J. C., and Bortoloti, R. (2021). Re-

lating, orienting and evoking functions in an IRAP

study involving emotional pictographs (emojis) used

in electronic messages. Journal of Contextual Behav-

ioral Science, 21:80–87.

Wittgenstein, L. (2007). Tractatus Logico-

Philosophicus. Cosimo Classics, New York. https:

//standardebooks.org/ebooks/ludwig-wittgenstein/

tractatus-logico-philosophicus/c-k-ogden.

Perception and Interpretation of Emoji in the Pedagogical Process: Aposterior Features of Artificial Digital Language

155