Psychological Security in the Conditions of using Information and

Communication Technologies

Larysa P. Zhuravlova

1 a

, Liubov V. Pomytkina

2 b

, Alla I. Lytvynchuk

1 c

,

Tetiana V. Mozharovska

1 d

and Valerii F. Zhuravlov

1 e

1

Polissia National University, 7 Staryi Blvd., Zhytomyr, 10008, Ukraine

2

National Aviation University, 1 Liubomyra Huzara Ave., Kyiv, 03058, Ukraine

Keywords:

Psychological Security, Traditional Learning, Distance Learning, Information and Communication Technolo-

gies, Participants of the Educational Process, Teachers of Higher Education Institutions.

Abstract:

The article substantiates the relevance and expediency of the study of psychological security of the personality

in the conditions of using information and communication technologies (ICT). The purpose of the research

is an empirical study of the psychological safety of teachers of higher education institutions in the conditions

of using information and communication technologies. The influence of traditional (classroom, offline) and

distance (online) types of training on the sense of security of teachers of higher education institutions in the

conditions of using ICT is analyzed. Today’s realities, in particular the global pandemic caused by the spread

of COVID-19 virus infection, have significantly accelerated the introduction and implementation of distance

learning and significantly expanded the range of participants in the educational process. Therefore, it has been

suggested that teachers of higher education institutions assess traditional (classroom, offline) learning as safer

than distance (online). The results of an empirical study of psychological safety in the conditions of using ICT

by teachers of higher education institutions are presented. A comparative analysis of the sense of security by

teachers of higher education institutions in the context of traditional (classroom, offline) and distance (online)

learning was performed. Associations of distance and traditional learning have been found to have significant

differences. Groups of concepts in which associations of respondents are invested (“negative”, “positive”,

“neutral”) are defined. It is analyzed that associations for the phrase “distance learning”, “full-time learning”

are located on three semantic “fields”: actions, states and characteristics of the referent of the word-stimulus;

actions, states and characteristics of other subjects; feelings and emotions. Differences in the perception

of distance and traditional learning by teachers depending on the time they spend on online learning were

identified. It is determined that the level of psychological security is equally mediocre in both traditional and

distance learning. Statistically significant relationships were found between the sense of security in online and

offline learning.

1 INTRODUCTION

Scientific and technological progress is rapidly gain-

ing momentum and covers all areas of personality’s

life activity. Today, no sphere of public life, includ-

ing educational, is effective without the involvement

and implementation of scientific and technical means.

The involvement of developments of scientific and

technological progress in the educational process is

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4020-7279

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2148-9728

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9805-7416

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9628-2994

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5020-2255

particularly rapid now – in a global pandemic caused

by the spread of viral infection COVID-19 (Pomytkin,

2020; Pomytkin and Pomytkina, 2020; Tkachuk et al.,

2021). One of the ways to implement information

and communication technologies is the introduction

of distance learning (Syvyi et al., 2020).

Distance learning is defined as an individual-

ized process of acquiring knowledge, skills, abili-

ties and ways of human cognitive activity, which oc-

curs mainly through the indirect interaction of distant

participants of the educational process in a special-

ized environment that operates on the basis of psy-

chological, pedagogical, information and communi-

cation technologies (zakon.rada.gov.ua, 2013). We

216

Zhuravlova, L., Pomytkina, L., Lytvynchuk, A., Mozharovska, T. and Zhuravlov, V.

Psychological Security in the Conditions of using Information and Communication Technologies.

DOI: 10.5220/0010930200003364

In Proceedings of the 1st Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology (AET 2020) - Volume 2, pages 216-223

ISBN: 978-989-758-558-6

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

can say that distance learning is implemented using a

set of modern technologies that ensure the process of

providing and receiving information in an interactive

mode with the use of information and communication

technologies by all participants in the educational pro-

cess.

It is obvious that the main role in the implemen-

tation of distance (online) education, as well as, in

fact, traditional (classroom, offline), is played by in-

formation and communication technologies. The lat-

ter, in turn, are defined as technologies for creat-

ing, accumulating, storing and accessing electronic

resources of educational programs and training ma-

terials, providing and supporting the educational pro-

cess using specialized software and means of infor-

mation and communication, including the Internet

(zakon.rada.gov.ua, 2013). It is the Internet that re-

veals the possibilities of virtual connection and com-

munications.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Almarashdeh (Almarashdeh, 2016), Barvinskaya

(Barvinskaya, 2020), Bobyliev and Vihrova

(Bobyliev and Vihrova, 2021), Bykov et al. (Bykov

et al., 2001), Chernyshov (Chernyshov, 2021),

Dos Santos (Dos Santos, 2020), Duell (Duell, 2008),

Finley (Finley, 2012), Gajek (Gajek, 2018), Giest

(Giest, 2004), Giest (Giest, 2008), Karadeniz (Karad-

eniz, 2009), Kukharenko and Oleinik (Kukharenko

and Oleinik, 2019), McGinnis (McGinnis, 2010),

Mills (Mills, 1997), Rourke and Anderson (Rourke

and Anderson, 2002), Seguin (Seguin, 2021), Sezer

(Sezer, 2016), Teplow (Teplow, 1996), Traxler

(Traxler, 2018), Weety (Weety, 1998), Wells (Wells,

2021) conducted scientific research in the direction

of theoretical, empirical and social aspects of the

introduction of distance learning, analyzed the

problems of the introduction of distance learning and

the features of the involvement of information and

communication technologies.

Empirical research on educational technologies

used in distance learning has become widely known.

In particular, Anderson and Rivera-Vargas (Anderson

and Rivera-Vargas, 2020) identified and critically sub-

stantiated the main dimensions of using digital tech-

nologies in distance education, which led to signifi-

cant changes, namely: reducing the quality of educa-

tion; restriction of application of new knowledge de-

velopment methods; copyright infringement; exces-

sive idealization of information and communication

technologies; violation of private information due to

the widespread use of social media in distance educa-

tion (Anderson and Rivera-Vargas, 2020).

At the same time, Anderson (Anderson, 2019)

notes that social media, as a tool of information and

communication technologies, is a major component

of commercial, entertainment and, of course, educa-

tional activities. Education has a unique opportunity

to control and improve their own practices through

the dissemination of social media, which are effec-

tive for all participants of the educational process. In

particular, teachers, educators and mentors have ad-

ditional opportunities to communicate with students.

An important aspect of this connection is the control

and intervention in the learning process in order to in-

crease the effectiveness of both teaching and learning.

New ways of finding, receiving and exchanging edu-

cational information are becoming available for learn-

ers (pupils, students) (Anderson, 2019).

Sancho-Gil et al. (Sancho-Gil et al., 2020),

Pomytkin et al. (Pomytkin et al., 2020) point out that

the development of ICT has caused excessive concern

about its ability to solve educational problems and im-

prove the quality of learning. Such a situation requires

the development and implementation of new digital

technologies in education for effective digital inclu-

sion in order to expand public knowledge about the

possibilities of using information technology in the

educational environment.

The urgent need for the implementation and im-

plementation of distance learning creates excessive

excitement and uncertainty among all participants of

the educational process. Thus, Anderson (Anderson,

2019) notes that the main difference between distance

learning and traditional is the exhaustion of its partic-

ipants.

Distance learning, accompanied by the intensive

use of information and communication technology

tools, in particular, the inclusion in the digital in-

formation environment of participants of the educa-

tional process, leads to a deterioration in psycholog-

ical well-being and information stress. The latter, in

turn, is associated with the long-term use of informa-

tion and communication technologies, in particular,

the Internet (Kislyakov, 2020).

Social networks, watching news, consuming in-

formation, etc. lead to increased information stress

and reduce the level of psychological security of the

personality. The problem of information and psycho-

logical security is related to such psychological as-

pects as the perception, preservation, processing and

use by participants in the educational process of a

certain information array (Krasnyanskaya and Tylets,

2019).

The concept of psychological security can be de-

scribed as a state of psychological safety and the abil-

Psychological Security in the Conditions of using Information and Communication Technologies

217

ity of the personality to withstand unpleasant exter-

nal and internal influences. Psychological security is

an important factor of interpersonal interaction (Ed-

mondson, 1999, 2004). The latter is significantly re-

duced in terms of distance learning, which is con-

firmed by scientific research. A study (Hu et al., 2018)

reported that the lower the level of psychological se-

curity of the personality, the higher the level of dis-

tance interaction. The dependence of a sense of psy-

chological security in terms of distance or traditional

learning is evidenced by the results of several studies.

In particular, the relationship between psychological

security and social networks is revealed (Soares and

Lopes, 2014), which is one of the main tools of inter-

action between participants in the educational process

in distance learning.

Given the significant amount of research on the

study of psychological security and information and

communication technologies, the aspect of psycho-

logical safety of teachers of higher education institu-

tions in the conditions of using ICT remains insuffi-

ciently studied.

The purpose of the research is an empirical study

of the psychological safety of teachers of higher edu-

cation institutions in the conditions of using informa-

tion and communication technologies. In our study,

we made assumptions that the teachers of higher edu-

cation institutions evaluate traditional (classroom, of-

fline) learning safer than distance (online) learning.

3 RESEARCH METHODS

The study of psychological safety in the use of

ICT was implemented during the autumn semester

of 2020. Teachers of higher education institutions

(N = 59) took part in the study, including 48 women

(81%) and 11 men (11%). The age of respondents

varies between 25–75 years, the largest share are

teachers aged 25–44 years (75%), 11 teachers aged

45–60 years (19%) and 4 teachers aged 61–75 years

(7%).

To study the features of psychological safety in

traditional (classroom, offline) and distance (imple-

mented as a measure to combat the spread of coro-

navirus disease (COVID-19)) forms of studying was

developed and implemented author’s questionnaire

“Psychological security in conditions of using ICT”.

Its validity and reliability were ensured by using the

method of independent expert evaluations. The ques-

tionnaire contained three components that assess both

the conditions of distance learning and its psycholog-

ical component: determining the intensity of involve-

ment in distance learning (time spent), the study of as-

sociations on different forms of learning and the sub-

jective level of psychological security (on a five-point

scale) during distance and full-time forms of educa-

tion.

The method of frames (schemes) was used for

qualitative and quantitative analysis of associations.

This method allows you to group associations by cer-

tain descriptive characteristics that can be applied to

abstract concepts: 1) actions, states and characteris-

tics of the word-stimulus, 2) actions, states, charac-

teristics of other subjects, 3) feelings and emotions

(Mironova, 2011) and the method of expert assess-

ments. Methods of mathematical statistics were used

for statistical processing of the obtained quantitative

data (descriptive statistics, comparison of dependent

samples (Student’s t-criterion), Spearman’s rank cor-

relation analysis). Automated data processing was

performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 26 and the

ArcGIS software packages.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

According to the results of empirical research, the fre-

quency hierarchy of associations for the phrases “dis-

tance learning” and “full-time learning” was revealed.

Analysis of the results shows that teachers of higher

education institutions associate the phrase “distance

learning” primarily with ICT: “computer” (6%), “In-

ternet” (6%), “Moodle, Classroom, Viber” (4%); with

an evaluative attitude: “fast” (4%), “imperfect” (4%),

also significant is the affective component, which has

a negative emotional color: “stress” (4%).

The hierarchy of associations for the phrase “full-

time education” differs significantly from the previ-

ous one. The main associations are aimed at inter-

action, and interpersonal connection – “communica-

tion” (17%); identification of specific characteristics

of direct interaction – “live communication” (13%),

“communication” (6%), “knowledge” (6%).

Qualitative analysis of reactions (associations)

based on the method of frames (Mironova, 2011) al-

lowed to make their qualitative characteristics.

Field 1. Actions, states and characteristics of the

word-stimulus. The phrase-stimulus “distance learn-

ing” is expressed through actions, states and char-

acteristics that describe the effectiveness of distance

learning, its impact on the physical and mental state

of the respondent: for example, “inappropriate”, “un-

desirable”, “low efficiency”, “exhausting”, “long”,

“simple “, etc. The characteristics of the phrase-

stimulus “full-time learning” mostly reflect its focus

on the communicative process, such as “communica-

tion”, “live communication”, “energy of live commu-

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

218

nication”, “simple”, “fast”.

Field 2. Actions, states, characteristics of other

subjects. In the associative chain of the phrase-

stimulus “distance learning”, the interiorization is

traced: the “other subject” is the respondent (for ex-

ample, “insomnia”, “control”, “day mode”, “sleep”).

At the same time, in the associative chain for the

phrase-stimulus “full-time study”, respectively - ex-

teriorization (for example, “students”, “I know where

the child is”, “friends”, “noise”, “fun”, “long time to

get to”, “waste of time”).

Field 3. Feelings and emotions. The associa-

tive chain of the phrase-stimulus “distance learning”

is characterized by the narrowness and uniformity of

emotional characteristics, such as “sadness”, “worry-

ing”, and so on. The associative chain of the phrase-

stimulus “full-time learning” is dominated by con-

cepts that characterize feelings and emotions. They

differ in variety and bright emotional color, such as

“fun”, “contact”, “attentive”, “emotions”.

With the help of expert assessments, the associ-

ations were grouped into three groups: “negative”,

“positive” and “neutral”. Negative associations in-

clude those that have an expressed negative evalu-

ation attitude or emotional coloring, such as “sad-

ness”, “horror”, “forced step”, “low efficiency”, and

so on. Neutral associations include those that reflect

events, objects, phenomena, objective reality, such

as the “Internet”, “audience”, “Zoom”, etc. Positive

associations include those that have a positive emo-

tional color or evaluation, such as “fun”, “live com-

munication”, “good feedback”, and so on. By assign-

ing a numerical value to each group of associations

(”0” = “negative”, “1” = “neutral”, “2” = “positive”)

and using methods of statistical data processing, it

was found that associations of teachers of higher ed-

ucation institutions regarding distance and traditional

education differ significantly (t = −4.801, p ≤ 0.012)

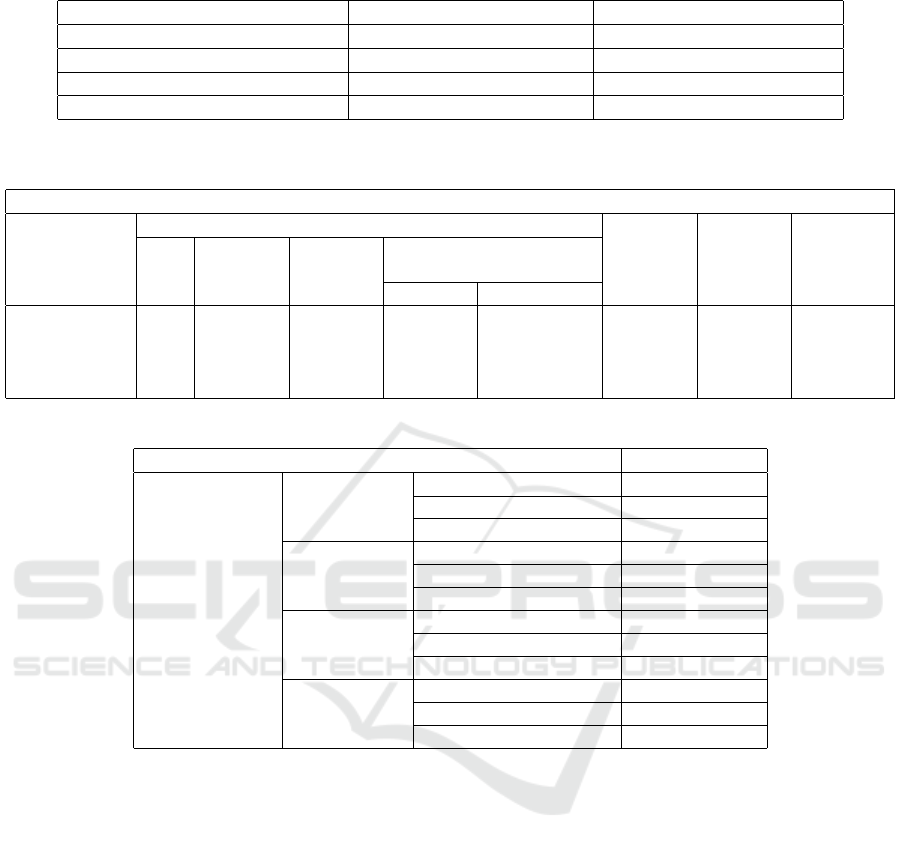

(table 1).

It should be noted that in each of the three fields,

respondents focused on the concept of time spent on

distance and full-time study and their characteristics,

such as “more time for themselves”, “fast”, “slow”,

“waste of time”, “all day”, “round-the-clock access”,

“work after work”, “no waste of time”, etc. Peculiari-

ties of the perception of distance learning by employ-

ees of higher education institutions depending on how

much time they spent on average during the working

week on distance learning are presented in table 2.

The most negative perception of distance learning

is perceived by respondents who have been involved

in it for less than 6 hours (58.3%). Respondents who

spend more than 18 hours a week on distance learn-

ing also rate it rather negatively. The smallest num-

ber (32.0%) of negative associations regarding dis-

tance learning have respondents who are involved in

it for 6–18 hours. It should be noted that the more

respondents were involved in distance learning, the

less positive (4.5%) and more neutral (50.0%) associ-

ations they have with it.

Those who spend an average of 6 to 18 hours a

week on distance learning tend to describe it most

positively.

The results of the analysis of associations for the

phrase-stimulus “full-time learning” are fundamen-

tally different from the previous ones (table 3). Most

positive associations (40.9%) regarding full-time ed-

ucation occur in teachers who spend the most time

(more than 18 hours) on distance learning, and the

least – in those who worked distantly the least (6

hours per week). The vast majority (61%) of re-

spondents generally have a neutral perception of tra-

ditional (classroom, offline) learning. It is worth not-

ing much lower rates of negative associations with the

phrase-stimulus “full-time learning”, compared with

distance (respectively, 3.4% and 42.4%).

For a more detailed interpretation of the pecu-

liarities of the perception of distance and full-time

learning, the subjective level of psychological secu-

rity feeling of teachers of higher education institutions

during the implementation of both forms of educa-

tion was determined (table 4). In general, respondents

rate their level of psychological security as equally

mediocre in distance and full-time learning ( ¯x = 2.808

and ¯x = 2.900, respectively).

However, we observe contradictions between the

emotional perception of online/offline learning and

the assessment of their own psychological security

in their implementation depending on the time of us-

ing ICT. Thus, full-time learning is assessed as the

most dangerous ( ¯x = 3.307) by teachers who are most

positive about it, and who spend more than 18 hours

a week on distance learning. The least dangerous

( ¯x = 2.423) full-time learning is for teachers who are

involved in distance learning for less than 6 hours.

The most dangerous ( ¯x = 3.305) feel in the online en-

vironment those who spend from 6 to 18 hours on it.

To find significant differences between the indi-

cators of experiencing a sense of security in the im-

plementation of online/offline learning by teachers of

higher education institutions we used calculations of

the Student’s t-criterion (table 5). No statistically

significant differences were found, but some trends

were indicated: teachers who are involved in distance

learning for less than 6 hours tend to perceive the

online environment as safer (t = 1.442, p ≤ 0.175),

those who work from 6 to 18 hours, on the contrary,

as more dangerous (t = −1.51, p ≤ 0.144). Those

Psychological Security in the Conditions of using Information and Communication Technologies

219

Table 1: Differences in associations of employees of higher education institutions about full-time and distance learning.

Paired Samples Test

Distance Paired Differences

t df Sig. 2-tailed

/

Mean

Std. Std. 95% Confidence

full Devia- Error Interval of the Difference

time tion Mean Lower Upper

-.593 .949 .123 -.840 -.345 -4.801 58 .012

Table 2: Emotional perception of distance learning by teachers with different times of using ICT.

Crosstabulation

Associations to the phrase-stimulus

Total“distance learning”

Negative Neutral Positive

Term of online

Less than 6

Count 7 3 2 12

% within 58.3 25.0 16.7 100.0

6-18

Count 8 11 6 25

study (hours) % within 32.0 44.0 24.0 100.0

More than 18

Count 10 11 1 22

% within 45.5 50.0 4.5 100.0

Total

Count 25 25 9 59

% within 42.4 42.4 15.3 100.0

Table 3: Emotional perception of full-time learning by teachers with different time of using ICT.

Crosstabulation

Associations to the phrase-stimulus

Total“full-time learning”

Negative Neutral Positive

Term of online

Less than 6

Count 1 7 4 12

% within 8.3 58.3 33.3 100.0

6-18

Count 1 16 8 25

study (hours) % within 4.0 64.0 32.0 100.0

More than 18

Count 0 13 9 22

% within 0.0 59.1 40.9 100.0

Total

Count 2 36 21 59

% within 3.4 61.0 35.6 100.0

who spent more than 18 hours distantly mediocrely

assessed their own safety both offline and online

(t=−0.731, p ≤ 0.473).

Spearman’s correlation analysis was used for a

more detailed interpretation (table 6). It was found

that there is a statistically significant relationship

between indicators of psychological safety in dis-

tance and offline learning for both respondents of

the general sample (r = 0.358, ρ ≤ 0.001) and

teachers who are involved distantly for 6-18 hours

(r = 0.528, ρ ≤ 0.001). We do not observe such

correlations in respondents who are engaged in on-

line learning for a small or extremely large amount of

time.

As the result of the study it was determined that

the feeling of psychological security and the percep-

tion of teachers of higher education institutions about

distance and traditional learning have certain specific

characteristics.

5 CONCLUSIONS

1. Psychological security is defined as a state of psy-

chological protection from external and internal

influences. In the conditions of distance learning

the feeling of psychological safety of its partic-

ipants decreases, in comparison with the condi-

tions of traditional (classroom) learning.

2. There are differences in the perception of dis-

tance and traditional (full-time) learning among

teachers of higher education institutions. Associa-

tions for the phrase “distance learning”, “full-time

learning” are located in three semantic “fields”:

teachers of higher education institutions associate

distance learning with ICT and with feelings and

emotions, full-time learning is associated with

communication and interaction with others. There

is a significant difference between distance and

traditional learning associations: distance learn-

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

220

Table 4: Level of psychological safety of teachers of higher education institutions ( ¯x).

Term of online learning (hours) Online (distance) learning Offline (full-time) learning

Less than 6 2.820 3.307

6-18 3.305 2.694

More than 18 2.576 2.423

Total 2.900 2.808

Table 5: The sense of security features of higher education institutions teachers with different time of using ICT in the

conditions of online/offline learning.

Paired Samples Test

Term of Paired Differences

t df Sig. 2-tailed

online

Mean

Std. Std. 95% Confidence

training Devia- Error Interval of the Difference

(hours) tion Mean Lower Upper

Total -.084 1.734 .225 -.536 .367 -.375 58 .709

More than 18 -.272 1.750 .373 -1.048 .503 -.731 21 .473

6-18 -.416 1.348 .275 -.986 .152 -1.51 23 .144

Less than 6 .846 2.115 .586 -.432 2.124 1.442 12 .175

Table 6: Relationships between psychological safety indicators in online/offline learning.

Sample/term of online training (hours) Offline/Online

Spearman’s rho

Total sample

Correlation Coefficient .358

∗∗

Sig. (2-tailed) .005

N 59

More than 18

Correlation Coefficient .241

Sig. (2-tailed) .280

N 22

6-18

Correlation Coefficient .528

∗∗

Sig. (2-tailed) .008

N 24

Less than 6

Correlation Coefficient .327

Sig. (2-tailed) .276

N 13

∗∗

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

ing is perceived more negatively than full-time

learning.

3. There is a statistically significant relationship be-

tween the feeling of psychological security of re-

spondents in distance learning and the feeling of

psychological security in offline learning. The

subjective level of feeling of psychological secu-

rity has average indicators, both in terms of dis-

tance and full-time learning. Teachers who spend

a lot of time online tend to perceive more danger-

ous full-time learning. The least dangerous are

those who are involved in distance learning for a

short time. The most dangerous in the online en-

vironment feel those who spent on it an average

of 6 to 18 hours.

4. Contradictions between the emotional perception

of online/offline learning and the assessment of

the level of their own psychological security in

their implementation depending on the time of us-

ing ICT were defined.

The research hypothesis was partially proved. We

see prospects for further research in the study of the

features of psychological security of all participants

in the educational process in a wide sample.

REFERENCES

Almarashdeh, I. (2016). Sharing instructors experience of

learning management system: A technology perspec-

tive of user satisfaction in distance learning course.

Computers in Human Behavior, 63:249–255.

Anderson, T. (2019). Challenges and opportuni-

ties for use of social media in higher educa-

tion. Journal of Learning for Development, 6(1).

https://jl4d.org/index.php/ejl4d/article/view/327.

Anderson, T. and Rivera-Vargas, P. (2020). A critical look

Psychological Security in the Conditions of using Information and Communication Technologies

221

at educational technology from a distance education

perspective. Digital Education Review, (37):208–229.

https://revistes.ub.edu/index.php/der/article/view/30917.

Barvinskaya, E. M. (2020). The impact of distance learn-

ing for the content and organization of solo academic

singing classes. Musical Art and Education, 8(4):107–

115.

Bobyliev, D. Y. and Vihrova, E. V. (2021). Problems and

prospects of distance learning in teaching fundamental

subjects to future mathematics teachers. Journal of

Physics: Conference Series, 1840(1):012002.

Bykov, V., Dovgiallo, A., and Kommers, P. (2001). Theoret-

ical backgrounds of educational and training technol-

ogy. International Journal of Continuing Engineering

Education and Life-Long Learning, 11(4-6):412–441.

Chernyshov, S. A. (2021). Massive shift of schools towards

distance learning in the estimates of a local pedagogi-

cal community. Obrazovanie i Nauka, 23(3):131–155.

Dos Santos, L. M. (2020). The motivation and experience of

distance learning engineering programmes students:

A study of non-traditional, returning, evening, and

adult students. International Journal of Education and

Practice, 8(1):134–148.

Duell, M. N. (2008). Distance Learning: Psychology On-

line.

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning

behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quar-

terly, 44(2):350–383.

Edmondson, A. C. (2004). Psychological safety, trust, and

learning in organizations: A group-level lens. In

Kramer, R. M. and Cook, K. S., editors, Trust and

distrust in organizations: Dilemmas and approaches,

pages 239–272. Russell Sage Foundation, New York.

Finley, S. (2012). Testing the limits of long-distance learn-

ing: Learning beyond a three-segment window. Cog-

nitive Science, 36(4):740–756.

Gajek, E. (2018). Curriculum integration in distance learn-

ing at primary and secondary educational levels on the

example of etwinning projects. Education Sciences,

8(1):1.

Giest, H. (2004). The formation experiment in the age of

hypermedia and distance learning. European Journal

of Psychology of Education, 19(1):45–64.

Giest, H. (2008). The formation experiment in the age of

hypermedia and distance learning.

Hu, J., Erdogan, B., Jiang, K., Bauer, T. N., and Liu, S.

(2018). Leader humility and team creativity: The role

of team information sharing, psychological safety,

and power distance. Journal of Applied Psychology,

103(3):313–323.

Karadeniz, S. (2009). Flexible design for the future of dis-

tance learning. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sci-

ences, 1(1):358–363.

Kislyakov, P. (2020). Psikhologicheskaya ustojchivost’ stu-

dencheskoj molodezhi k informaczionnomu stressu v

usloviyakh pandemii covid-19. Perspectives of Sci-

ence & Education, 47(5):343–356.

Krasnyanskaya, T. M. and Tylets, V. G. (2019). Techno-

logical components for providing the information and

psychological safety of personality in the conditions

of distance learning. Information Technologies and

Learning Tools, 73(5):249–263. https://journal.iitta.

gov.ua/index.php/itlt/article/view/2546.

Kukharenko, V. and Oleinik, T. (2019). Open distance

learning for teachers. CEUR Workshop Proceedings,

2393:156–169.

McGinnis, M. (2010). John Tracy clinic/university of San

Diego graduate program: A distance learning model.

Volta Review, 110(2):261–270.

Mills, B. D. (1997). Pilot testing an instrument for deter-

mining the goal orientation of distance learning grad-

uate students. Journal of Human Movement Studies,

33(3):93–118.

Mironova, N. I. (2011). Associative experiment: methods

of data analysis and analysis based on the universal

scheme. Voprosy psikholingvistiki, (14):108–119.

https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/assotsiativnyy-

eksperiment-metody-analiza-danyh-i-analiz-na-

osnove-universalnoy-shemy.

Pomytkin, E. O. (2020). Strategy and tactics of

conscious psychological counteraction of hu-

manity to viral diseases. In Kremen, V. H.,

editor, Psychology and education infighting

COVID-19: online manual, pages 17–30. Yurka

Lyubchenka. https://drive.google.com/file/d/

1yDw7bZfGo0Ny94KsbcBJWfDlcZ8wHXN9/view.

Pomytkin, E. O. and Pomytkina, L. V. (2020). Strategy

and tactics of conscious psychological counteraction

of humanity to viral diseases. In Rybalka, V., Samod-

ryn, A., Voznyuk, O., Morgun, V., Pomytkin, E., and

Samodryna, N., editors, Philosophy, psychology and

pedagogics against COVID-19, pages 119–133. Olek-

siy Yevenok, Zhytomyr. http://emed.library.gov.ua/

jspui/handle/123456789/160.

Pomytkin, E. O., Pomytkina, L. V., and Ivanova, O. V.

(2020). Electronic resources for studying the emo-

tional states of new ukrainian school teachers during

the covid-19 pandemic. Information Technologies and

Learning Tools, 80(6):267–280. https://journal.iitta.

gov.ua/index.php/itlt/article/view/4179.

Rourke, L. and Anderson, T. (2002). Using web-based,

group communication systems to support case study

learning at a distance. International Review of Re-

search in Open and Distance Learning, 3(2):105–119.

Sancho-Gil, J. M., Rivera-Vargas, P., and Mi

˜

no-Puigcerc

´

os,

R. (2020). Moving beyond the predictable failure of

ed-tech initiatives. Learning, Media and Technology,

45(1):61–75.

Seguin, M. (2021). What would Jesus do in a distance learn-

ing mode of teaching? Kairos, 15(1):49–62.

Sezer, B. (2016). Faculty of medicine students’ attitudes

towards electronic learning and their opinion for an

example of distance learning application. Computers

in Human Behavior, 55:932–939.

Soares, A. and Lopes, M. P. (2014). Social networks

and psychological safety: A model of contagion.

Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management,

7(5):995–1012. https://www.jiem.org/index.php/jiem/

article/view/1115.

AET 2020 - Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

222

Syvyi, M. J., Mazbayev, O. B., Varakuta, O. M., Panteleeva,

N. B., and Bondarenko, O. V. (2020). Distance learn-

ing as innovation technology of school geographical

education. CEUR Workshop Proceedings, 2731:369–

382.

Teplow, D. (1996). Distance learning and just-in-time clini-

cal education for the 21st century behavioral health-

care provider. Behavioral Healthcare Tomorrow,

5(4):39–78.

Tkachuk, V., Yechkalo, Y., Semerikov, S., Kislova, M.,

and Hladyr, Y. (2021). Using Mobile ICT for Online

Learning During COVID-19 Lockdown. In Bollin,

A., Ermolayev, V., Mayr, H. C., Nikitchenko, M.,

Spivakovsky, A., Tkachuk, M., Yakovyna, V., and

Zholtkevych, G., editors, Information and Communi-

cation Technologies in Education, Research, and In-

dustrial Applications, pages 46–67, Cham. Springer

International Publishing.

Traxler, J. (2018). Distance learning—predictions and pos-

sibilities. Education Sciences, 8(1):35.

Weety, L. S. C. (1998). The influence of a distance-

learning environment on students’ field depen-

dence/independence. Journal of Experimental Edu-

cation, 66(2):149–160.

Wells, R. (2021). The impact and efficacy of e-counselling

in an open distance learning environment: A mixed

method exploratory study. Journal of College Student

Psychotherapy.

zakon.rada.gov.ua (2013). Polozhennia pro dystantsi-

ine navchannia. https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/

z0703-13#Text.

Psychological Security in the Conditions of using Information and Communication Technologies

223