Analyzing Privacy Practices of Existing mHealth Apps

Aarathi Prasad, Matthew Clark, Ha Linh Nguyen, Ruben Ruiz and Emily Xiao

Department of Computer Science, Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, New York, U.S.A.

Keywords:

Apps, Mobile Health, Mental Health, Privacy, Smartphone, Permissions.

Abstract:

Given students’ reliance on smartphones and the popularity of mobile health apps, care should be taken to pro-

tect students’ sensitive health information; one of the major potential risks of the disclosure of this data could

be discrimination by insurance companies and employers. We conducted an exploratory study of 197 existing

smartphone apps, which included 98 mobile health apps, to study their data collection, usage, sharing, storage

and deletion practices. We present our findings from the analysis of privacy policies and permission requests

of mHealth apps, and propose the need for a usable health data dashboard for users to better understand and

control how their health data is collected, used, shared and deleted.

1 INTRODUCTION

College students are increasingly turning to mobile

health (mHealth) apps (Yuan et al., 2015; Cho et al.,

2014) to monitor their diet and physical fitness (Mar-

tin et al., 2015; Gowin et al., 2015), learn about

sexual health (Richman et al., 2014), and improve

their mental health (Kern et al., 2018). Unable to

address the needs of all students, counseling centers

of several universities are also encouraging students

to use mHealth apps and have listed on their web-

sites (Center for Collegiate Mental Health Research

Team, 2016; Reetz et al., 2016), a list of mental health

apps that students can download and use to manage

and improve their anxiety, stress and depression, to

help students recover from drug and alcohol abuse

and to prevent and get help in incidents of sexual vi-

olence (Amherst College, 2019; Middlebury College,

2019).

Given young adults’ reliance on smart-

phones (Vorderer et al., 2016), and the popularity of

mHealth apps, care should be taken to protect their

personal health data; one of the major potential risks

of the disclosure of a user’s personal health data

could be discrimination by insurance companies and

employers. Recently, three mobile health apps were

declared by the New York State Attorney General’s

office to be misleading consumers and engaging in

questionable privacy practices (NY Attorney General,

2017). Despite common perception that young adults

share everything about their lives and desire no

privacy, Boyd discovered that teenagers want privacy

as a way to assert control over what they share (Boyd,

2014); the teenagers in her interviews should be in

college now and we expect they continue to have

similar expectations of privacy.

We conducted an exploratory study to understand

the data collection, usage, sharing, storage and dele-

tion practices of existing mHealth apps. Our research

contributions are as follows:

• We present the privacy practices of 98 mHealth

apps available on the Google Play Store.

• We compare the privacy policies and permission

requests of 98 mHealth apps with 99 non-mHealth

apps.

• We highlight the lack of transparency in data col-

lection, usage, storage and deletion policies across

different types of mHealth apps.

• We propose the need to extend existing usable

health data dashboards to highlight usage, shar-

ing, storage and deletion of health data, in addi-

tion to data collection.

Even though the motivation for this work is our

concern about young adults’ increased use of mHealth

apps, we expect our research to improve privacy prac-

tices of mHealth apps can benefit all mHealth app

users with privacy concerns.

2 BACKGROUND

The United States Department of Health and Human

Services (HHS) issued the Health Insurance Portabil-

ity and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) to de-

fine how health organizations could use and disclose

Prasad, A., Clark, M., Nguyen, H., Ruiz, R. and Xiao, E.

Analyzing Privacy Practices of Existing mHealth Apps.

DOI: 10.5220/0009059605630570

In Proceedings of the 13th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2020) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 563-570

ISBN: 978-989-758-398-8; ISSN: 2184-4305

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

563

an individual’s health information and to help indi-

viduals better understand and control this use and dis-

closure of their information (Department of Human

and Health Services, 2013). The health organizations,

referred to as “covered entities” include healthcare

providers, insurance companies, government health-

care programs and software vendors working with

these organizations. mHealth apps are typically not

subjected to HIPAA since most existing mHealth apps

are intended to help a user monitor their health and

wellness for personal use. HIPAA will not apply to

such mHealth apps even if the user downloaded the

data collected by the app and shared it with their

physician, unless the app developer was working di-

rectly with the physician and both parties had signed

a legal contract.

On the other hand, in Europe, the General Data

Protection Regulation (GDPR) on data protection and

privacy, approved in 2016, applies to all data col-

lected about European Union (EU) citizens, even by

mHealth apps. Researchers have, since then, listed

guidelines on how to translate GDPR regulations to

practice in mobile health (Muchagata and Ferreira,

2018), created usable interfaces to present data ac-

cording to GDPR’s guidelines (Raschke et al., 2018),

and developed ways to evaluate privacy policies us-

ing machine learning (Tesfay et al., 2018). How-

ever, a recent study showed that privacy policies of

smartphone apps were changed to reflect some por-

tions of GDPR but were still not as transparent to meet

GDPR’s guidelines (Mulder, 2019).

Privacy policies are legal documents that disclose

how companies collect users’ personal data when they

use websites or smartphone apps, how this informa-

tion is used, shared and with whom and for what rea-

sons, and how it is stored. A 2016 study conducted

by the Future of Privacy Forum revealed that 30% of

health apps do not even have privacy policies (Future

of Privacy Forum, 2016).

Another way to determine whether an app col-

lects sensitive data is through permission requests; re-

quests to access sensitive data are categorized as dan-

gerous permissions in Android. With the introduction

of app permissions, apps need to explicitly request for

the user’s permission before using certain smartphone

features to access user data such as contacts or calen-

dar, to record video or audio using camera or micro-

phone or to connect to an external wearable sensor.

Several studies have addressed the privacy prac-

tices of mHealth apps. Dehling et al. presented how

information collected by 24,405 health-related apps

in iOS and Android app stores could lead to pri-

vacy and safety concerns due to data leaks, errors and

loss (Dehling et al., 2015). Researchers have also ad-

dressed privacy issues in specific categories of mobile

health apps, such as headache diaries (Minen et al.,

2018), medication apps (Grindrod et al., 2016), men-

tal health apps (Loughlin et al., 2019; Parker et al.,

2019) diabetes apps (Blenner et al., 2016) and smok-

ing and depression apps (Huckvale et al., 2019).

In this paper, we present an exploratory analysis of

privacy practices of existing mHealth apps and com-

pare them with non-mHealth apps.

3 METHODS

We collected information about privacy practices of

200 Android applications. We considered apps that

appeared on the Google Play Store instead of the iOS

App Store, since App Store has a curated model, with

stricter policies for acceptance (McAllister, 2010).

We selected 100 mHealth apps using keywords such

as “mental health”, “depression”, “health”, “fitness”,

“anxiety”, and “stress”, and 100 apps from the list of

top applications on Google Play Store, while ensuring

that applications were only included in the list once.

We grouped the health applications into six main

categories.

• Trackers: Apps that allow users to collect health

data and monitor their progress over time, e.g.,

Fitbit (Fitbit, 2019).

• Guides: Apps that provided generic guidance,

without personalizing information based on the

user’s specific data, e.g., HeadSpace (HeadSpace,

2019).

• Medical Records: Apps that managed users’

health records, e.g., MyCigna (Cigna, 2019).

• Diagnosis: Apps that provide diagnosis, e.g.,

Moodtools (MoodTools, 2019).

• Collaborative: Apps that allow users to share

health data, e.g., Youper (Youper, 2019).

• Others: Apps that did not fit the above categories,

e.g., apps that are used only by employees of a

certain company such as the TTEC Health and

Wellness app (TTec, 2019).

The tracker and guide categories were further divided

into five subcategories to separate apps that tracked

or provided guidance on medication, fitness, men-

tal health, intimate (pregnancy, fertility and menstru-

ation) and physiological data. For example, Pillsy

tracks medications, while Period Tracker Clue tracks

menstrual cycle and fertility data.

Similarly, the collaborative apps were divided into

three subcategories, based on who users could collab-

orate and share their information with – health profes-

sionals, non-health professionals such as family and

friends and other users or a chat bot. For example,

HEALTHINF 2020 - 13th International Conference on Health Informatics

564

Period Tracker Clue allows users to share data with

family and friends, while Youper allows users to in-

teract with a chat bot.

Three researchers independently categorized each

app into the sixteen subcategories based on the goals

listed in the app description and used a majority vote

to determine the subcategories.

Naturally, some apps included services from more

than one category. Those apps were classified mul-

tiple times, once for each category they fit into. The

average app has 1.88 categories. For example, Period

Tracker Clue had three categories - intimate tracker,

guide and non-professional collaboration.

We did not create categories for the non mHealth

apps, since these apps were already assigned cate-

gories on the Google Play Store. Our 100 apps were

among 20 categories, including but not limited to en-

tertainment, social, utility, finance, shopping, games,

family (family-friendly content) and sports.

For each app, we collected the following factors

from the description and privacy policies. From the

descriptions, we collected

• App information such as app name, developer,

number of installations, app rating, price, content

rating (e.g., everyone, teen),

• Type of app (e.g., social, navigation, health and

wellness),

• Goals (e.g., track steps, play soothing sounds),

and

• List of permissions (e.g., location, microphone,

camera, file access)

By reviewing privacy policies, we determined:

• What user data is collected,

• How information is used,

• Whether the policies describe users’ rights,

• How and where user data is stored, and whether it

is transmitted in encrypted form,

• Whether information be deleted, and how, and

what information is retained by the company on

their servers, and

• Whether third parties have access to the informa-

tion

Finally, we also coded the data collected from

the descriptions, privacy policies and list of requested

permissions and used the codes to do an exploratory

analysis, as well as quantitative analysis using inde-

pendent and chi-squared t-tests.

4 FINDINGS

Out of the 200 apps, we excluded one non-mHealth

app and two mHealth apps from our analysis since

they were deleted by the time this paper was written.

We present findings from our analysis of privacy poli-

cies and app permission requests.

Privacy Policies

97 out of 99 top apps and 82 out of 98 mHealth apps

included a privacy policy. Using independent t-tests,

we discovered that apps with greater than or equal to

10 million installations each were more likely to have

a privacy policy than those with less than 10 million

installations (p<0.001); out of the 83 apps that have

greater than or equal to 10 million installations, only

10 are mHealth apps. However, we did not see a simi-

lar trend when considering an app’s user rating. Using

a chi-squared test, we determined, with 99.9% confi-

dence, that non-mHealth apps were more likely than

mHealth apps to have a privacy policy.

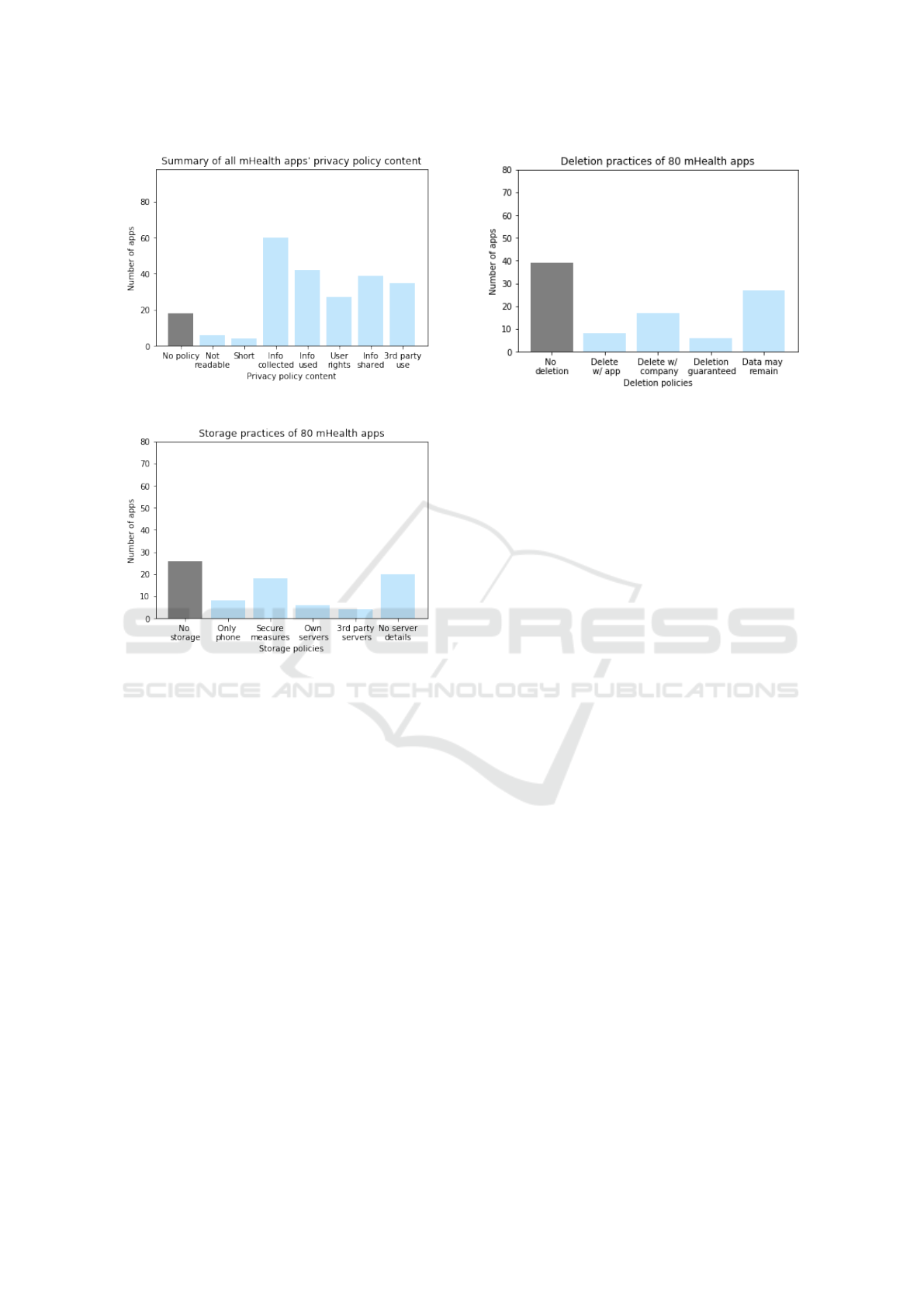

Figure 1 summarizes our findings from analyzing

the privacy policies of the 80 mHealth apps. Among

the 18 mHealth apps without privacy policies, 4 apps

were fitness trackers, 3 mental health trackers, and 2

physiological trackers. Among the 80 mHealth apps

with the privacy policy, 6 policies were in a language

other than English (with no English translation); four

of these apps were fitness or mental health trackers.

4 apps had policies that were too short and contained

no information about what data was collected, shared

or stored; two of these apps were trackers.

Data Collection: Even though 60 out of the 80 apps

had policies that presented a list of data that was col-

lected by the company, only as few as five apps in-

cluded details about the health data that was collected;

the five apps were all trackers. The other 55 apps

mostly described the collection of personally identi-

fying information such as name, email address, finan-

cial information such as credit cards and technical in-

formation such as device id, and cookies.

Data Use: Privacy policies of 42 out of the 80 apps

described how the apps (and the company) used the

data – most of the apps indicated that the data was

used to improve the services provided to the user. 39

apps mentioned what data was shared with third par-

ties, while 35 apps also described how third parties

used the data; these third parties included companies

that hosted the data on their servers (e.g., Amazon,

Google), and facilitated single sign on services (e.g.,

Google, Facebook). Only 27 out of the 80 apps pre-

sented information about the user’s rights to privacy

and control over their information.

Data Storage: Figure 2 summarizes our find-

ings from analyzing the storage practices of the 80

mHealth apps with privacy policies. 26 out of the 80

apps contained privacy policies that did not address

how the data collected was stored – 9 of these apps

Analyzing Privacy Practices of Existing mHealth Apps

565

Figure 1: Privacy policy content.

Figure 2: Storage policies.

were fitness or mental health trackers. 8 apps explic-

itly mentioned that all data collected was stored only

on the phone, and the user had the option to use a

cloud service of their choice for backup; 7 of these

apps were fitness or mental health trackers and one

was an app that facilitated communication with non-

professionals.

18 out of the 80 apps used encryption, either

for transmission or storage. Privacy policies of 4

apps revealed that user data was hosted on third-party

servers, while 6 apps described that data was stored

on their own servers (though it was not clear if they

used hosting services provided by third parties). On

the other hand, privacy policies of 20 apps mentioned

a server but gave no details about it; out of these 20, 7

apps were fitness, intimate or mental health trackers.

Data Deletion and Retention: Figure 3 summarizes

our findings from analyzing the deletion and retention

practices of the 80 mHealth apps with privacy poli-

cies. 39 out of the 80 mHealth apps did not address

any procedures for users to delete their information.

Out of the 39, 13 apps were fitness, mental health,

physiological, medication or intimate trackers.

Among the 41 out of 80 apps that contained some

Figure 3: Deletion policies.

procedures for deletion, 8 apps allowed users to delete

directly from the app, whereas 17 apps required the

users to contact the company. 6 apps contained pri-

vacy policies that guaranteed user data was deleted

from all servers, whereas 27 apps described how data

may remain on their servers even after the users re-

quested their data to be deleted. Out of these 27 apps,

10 were fitness, physiological, mental health or med-

ication trackers.

App Permissions

86 out of 99 non-mHealth apps and 70 out of 98

mHealth apps requested dangerous permissions; these

apps accessed sensitive data from the phone’s camera,

microphone, body sensors, GPS sensor, call and SMS

logs, file storage, calendar or user contacts. Using in-

dependent t-tests, we discovered that apps with more

than 10 million installations each were more likely

to request dangerous permissions than those with less

than 10 million installations (p<0.01); 10 mHealth

and 73 non-mHealth apps have more than 10 million

installations. However, we did not see a similar trend

when considering an app’s user rating.

Using a chi-squared test, we determined, with

90% confidence, that non-mHealth apps are more

likely to request dangerous permissions than an

mHealth app.

Using a chi-squared test, we also determined, with

95% confidence, that mHealth trackers were more

likely to request dangerous permissions than guides.

Finally, we also analyzed the dangerous permis-

sion requests by app category; due to limited space,

we only present details about the dangerous permis-

sion requests by mHealth apps.

Body Sensors: Six out of 98 mHealth apps and

zero non-mHealth apps requested permission to ac-

cess body sensors. If this permission is granted, an

HEALTHINF 2020 - 13th International Conference on Health Informatics

566

app can connect to external body and wearable sen-

sors. All six mHealth apps are fitness and physiologi-

cal trackers.

Calendar: 8 mHealth apps and 4 non-mHealth apps

requested permission to access the user’s calendar. If

this permission is granted, an app can read, create,

edit or delete calendar events. The mHealth apps in-

cluded fitness trackers and guides, a medical records

app, and medication and mental health guides.

Camera: 21 mHealth and 32 non-mHealth apps re-

quested permission to access the phone’s camera.

If this permission is granted, an app can use the

phone camera to take photos and record videos. The

mHealth apps included fitness, mental health, phys-

iological and intimate trackers, fitness and mental

health guides, a collaborative app and a medical

records app.

Contacts: 27 mHealth and 39 non-mHealth apps re-

quested access to user contacts. If this permission is

granted, an app can read, create or edit a user’s con-

tact list and access all list of accounts on the phone.

The mHealth apps included fitness, mental health and

intimate trackers, fitness and mental health guides, a

collaborative app and a medical records app.

Location: 29 mHealth apps and 36 non-mHealth

apps requested access to location. If this permission

is granted, an app can access the user’s approximate

(using cellular base stations and Wi-Fi access points)

and exact location (using GPS). The mHealth apps in-

cluded fitness, mental health, and intimate trackers,

fitness and mental health guides, a collaborative app

and a medical records app.

Microphone: 10 mHealth apps and 20 non-mHealth

apps requested access to phone’s microphone. If this

permission is granted, an app can use your micro-

phone to record audio. The mHealth apps included fit-

ness and mental health trackers, mental health guides,

a collaborative app and a medical records app.

Phone: 36 mHealth apps and 37 non-mHealth apps

requested access to phone feature. If this permission

is granted, an app can know the user’s phone number,

access ongoing call status, make and end calls, track

who calls the user, add voicemail, use VoIP and redi-

rect calls. The mHealth apps included fitness, mental

health, and intimate trackers, fitness and mental health

guides, and diagnosis, medical records and collabora-

tive apps.

SMS: 3 mHealth apps and 2 non-mHealth apps re-

quested access to sms. If this permission is granted,

an app can read, receive and send SMS and MMS

messages. All 3 mHealth apps were fitness apps.

Storage: 61 mHealth apps and 78 non-mHealth apps

requested access to file storage. If this permission is

granted, an app can read and write to the phone’s in-

ternal or external storage. The mHealth apps included

fitness, mental health, and intimate trackers, fitness

and mental health guides, collaborative apps and a di-

agnosis app.

Call Log: 4 mHealth apps and 4 non-mHealth apps

requested access to call logs. If granted permission,

an app can read and edit call logs. The mHealth apps

included fitness tracker and guides, and collaborative

apps.

An exploratory analysis indicates that mHealth

and non-mHealth apps request for data they do not

seemingly need and are consistent with findings from

prior work (Felt et al., 2011; Jeon et al., 2012; Wei

et al., 2012); for example, why would an mHealth

guide app and an entertainment app need access to

call logs? On the other hand, body sensors are ac-

cessed only by fitness and physiological trackers,

which is expected behavior. However, in most cases,

there are no clear reasons given in the description of

the apps for why the apps need access to the sensitive

data. For example, the medical records app requested

for all dangerous permissions except body sensors,

SMS, call log and storage.

5 DISCUSSION

mHealth apps are not as popular as the non-mHealth

apps, but adoption of mHealth is rapidly growing and

the number of mHealth apps available on the app

stores have grown significantly in the past five years.

46 out of the 98 mHealth apps we looked at had over

100,000 installations, out of which 22 had more than

1 million installations each. So it is important to ad-

dress their privacy practices and discuss ways to im-

prove privacy controls for health data.

Specific Privacy Policies for Health Data: Only as

few as five apps explicitly mentioned the health infor-

mation that they collect and how it is used.One of the

reasons could be the generic nature of privacy poli-

cies, i.e., most companies had one privacy policy for

all their products including websites and smartphone

apps. However, different types of health data have dif-

ferent levels of sensitivity, and also depends on how

it is used and how it is shared and with whom (Prasad

et al., 2012). If the apps do not disclose who the health

data is shared with and in what format and how it is

used, the user may risk having their data disclosed in

a manner that does not meet their expectations and

may feel embarrassed, or frustrated later when they

become aware of it. For example, only as few as two

apps among the 80 with privacy policies talked about

anonymizing the data before sharing with third par-

ties.

Analyzing Privacy Practices of Existing mHealth Apps

567

Storage and Deletion Policies: Privacy policies of

26 out of the 80 apps did not address how the data

collected was stored. Also, different privacy laws may

apply to the data, depending on the location of the

server that stores it. Apps should also be transparent

about how the data is stored and transmitted, and only

18 out of the 80 apps mentioned encrypted channels

for transmission.

Only 41 out of the 80 apps addressed whether

data could be deleted. Both HIPAA and GDPR

have guidelines on erasing personal data, but as was

discussed earlier, HIPAA does not apply to most

mHealth apps, and GDPR has not been implemented

by most mHealth apps; one issue could be that these

laws are difficult to interpret for the lay users.

Except for the five apps that mentioned health

information in their privacy policies, the other 75

mHealth apps only addressed storage and deletion for

the data they listed, which included identifying infor-

mation such as name and email address. Given the

sensitive nature of health information, it is important

for users to be aware of where their data is being

stored, how long it will be stored, and whether it is

possible to delete this data. For example, a college

student may not want their future employer to know

their smoking and drinking habits, and that they were

taking anti-depressants – if the company provides no

way for the individual to delete the information, the

data may get shared, sometimes inadvertently, if the

data remains with the company.

Transparency : Even though we did not conduct a

thorough investigation of whether mHealth apps actu-

ally needed the sensitive data they requested to access,

several mHealth apps requested for access to data that

they did not seemingly need for their functioning. For

example, while it was obvious why a fitness tracker

would need access to body sensors, there was no ex-

planation given as to why a fitness guide would need

access to call logs.

Need for Health Data Dashboard: Research shows

people do not read privacy policies (Jensen et al.,

2005), may not understand what data is collected and

shared since the policies are hard to read (Jensen and

Potts, 2004) and struggle with making privacy deci-

sions based on available information about what data

is collected, and how it is collected, stored, shared and

retained (Acquisti and Grossklags, 2005). Reeder et

al. developed Expandable Grid as a means to provide

a usable interface for users to better interpret com-

puter security policies (Reeder et al., 2008), Cranor et

al. created Privacy Bird to address the need for a us-

able interface to help users understand privacy poli-

cies (Cranor et al., 2006), while Lin et al. used ma-

chine learning to identify a small set of privacy pro-

files to help users make better decisions about pri-

vacy when installing apps (Lin et al., 2014). We pro-

pose a dashboard specifically for health data that lists

all health data collected by mHealth apps, but also

presents how the data is used, shared, stored and re-

tained.

Health dashboards already exist on iOS and An-

droid phones. Both iOS Health and Google Health

display every health data point that is collected, as

well as daily and weekly summaries of the health data

and also provide a list of all apps on the phone that can

access and modify health data. We propose extending

this dashboard to also facilitate ways to present

• How the health data is used by the company and

in what form (e.g., every data point or daily or

weekly summaries, is it anonymized and aggre-

gated before use?).

• How the health data is stored, i.e., is it stored only

on the phone, hosted on the servers owned by

the development company, hosted on third-party

servers, and which countries are the servers lo-

cated.

• Who the health data is shared with, i.e., insurance

companies, third-party companies that provide

the sign-in functionality, ad companies, health

providers, and family and friends, and in what

form. Prior research showed that individuals ex-

hibited different behavior when sharing with dif-

ferent people and groups, and were more inter-

ested in sharing health data when they felt the

data was useful to the person or group receiving

it (Prasad et al., 2012).

• Whether the data can be deleted, and if so, how

to delete the data and what still is retained by the

company.

The dashboard could use privacy icons to make it

more readable (Mozilla, 2011).

Designing such an interface can be challenging –

too much information may overwhelm the user and

the way the information is framed could influence a

user to under- or over-share in a manner conflicting

with their privacy preferences (Adjerid et al., 2013).

As future work, we plan to work with artists to design

the health data dashboard, and also plan to develop

and evaluate an app prototype.

5.1 Limitations

Given the exploratory nature of our study, we only

used a small sample size of 197 apps; we cannot

guarantee that this is a representative sample of all

mHealth and non-mHealth apps in the Google Play

Store.

In order to understand data collection, usage, shar-

HEALTHINF 2020 - 13th International Conference on Health Informatics

568

ing, storage and deletion practices of apps, we col-

lected data from the descriptions, privacy policies and

requested permissions manually, even though prior

research shows that apps may sometimes behave dif-

ferently from their privacy policies (Mulder, 2019;

Huckvale et al., 2019) and may have access to more

data (Felt et al., 2011; Jeon et al., 2012; Wei et al.,

2012). Our intention was to study the privacy policies

and permission requests to understand what policies

apps claim to follow, not their actual behavior.

6 CONCLUSIONS

We conducted an exploratory study of 198 existing

smartphone apps including 98 mHealth apps to study

their data collection, storage and deletion practices.

We uncovered several issues with the privacy policies

and permission requests of the mHealth apps. Only

five apps out of the 80 with privacy policies indicated

what health data was collected about the user. 26 apps

did not address how data was stored (9 tracked user

health data), while 39 apps did not address any pro-

cedures for deleting user data (13 tracked user health

data). Similarly, several mHealth apps had access to

sensitive user data that they did not seemingly need

for their functioning with no explanation provided as

to why the data was required. To address the lack

of transparency of privacy practices, we proposed ex-

tending existing health data dashboards to help users

better understand the collection, storage, retention

and sharing of their sensitive data.

REFERENCES

Acquisti, A. and Grossklags, J. (2005). Privacy and ratio-

nality in individual decision making. IEEE Security

Privacy, 3(1):26–33.

Adjerid, I., Acquisti, A., Brandimarte, L., and Loewen-

stein, G. (2013). Sleights of privacy: Framing, disclo-

sures, and the limits of transparency. In Proceedings

of the Ninth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Secu-

rity (SOUPS), pages 9:1–9:11, New York, NY, USA.

ACM.

Amherst College (2019). Mental health apps.

Blenner, S. R., K

¨

ollmer, M., Rouse, A. J., Daneshvar, N.,

Williams, C., and Andrews, L. B. (2016). Privacy

Policies of Android Diabetes Apps and Sharing of

Health Information. Journal of the American Medi-

cal Association, 315(10):1051–1052.

Boyd, D. (2014). It’s Complicated : the Social Lives of

Networked Teens. Yale University Press.

Center for Collegiate Mental Health Research Team (2016).

2015 Annual Report. Technical report, University of

Pennsylvania.

Cho, J., Quinlan, M. M., Park, D., and Noh, G.-Y. (2014).

Determinants of adoption of smartphone health apps

among college students. American Journal of Health

Behavior, 38(6):860–870.

Cigna (2019). MyCigna mobile app.

Cranor, L. F., Guduru, P., and Arjula, M. (2006). User inter-

faces for privacy agents. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum.

Interact., 13(2):135–178.

Dehling, T., Gao, F., Schneider, S., and Sunyaev, A. (2015).

Exploring the Far Side of Mobile Health: Information

Security and Privacy of Mobile Health Apps on iOS

and Android. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 3(1).

Department of Human and Health Services (2013). Sum-

mary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule.

Felt, A. P., Chin, E., Hanna, S., Song, D., and Wagner, D.

(2011). Android permissions demystified. In Proceed-

ings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer and

Communications Security, CCS ’11, pages 627–638,

New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Fitbit (2019). Fitbit.

Future of Privacy Forum (2016). FPF Mobile Apps Study.

Technical report, Future of Privacy Forum.

Gowin, M. J., Cheney, M. K., Gwin, S., and Wann, T. F.

(2015). Health and fitness app use in college students:

A qualitative study.

Grindrod, K., Boersema, J., Waked, K., Smith, V., Yang, J.,

and Gebotys, C. (2016). Locking it down: The privacy

and security of mobile medication apps. Canadian

Pharmacists Journal, 150(1):60–66.

HeadSpace (2019). HeadSpace: your guide to health and

happiness.

Huckvale, K., Torous, J., and Larsen M, E. (2019). As-

sessment of the Data Sharing and Privacy Practices of

Smartphone Apps for Depression and Smoking Ces-

sation. JAMA Network Open, 2(4).

Jensen, C. and Potts, C. (2004). Privacy Policies As

Decision-making Tools: An Evaluation of Online Pri-

vacy Notices. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Confer-

ence on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages

471–478, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Jensen, C., Potts, C., and Jensen, C. (2005). Privacy Prac-

tices of Internet Users: Self-reports Versus Observed

Behavior. International Journal on Human-Computer

Studies, 63(1-2):203–227.

Jeon, J., Micinski, K. K., Vaughan, J. A., Fogel, A., Reddy,

N., Foster, J. S., and Millstein, T. (2012). Dr. android

and mr. hide: Fine-grained permissions in android ap-

plications. In Proceedings of the Second ACM Work-

shop on Security and Privacy in Smartphones and Mo-

bile Devices, SPSM ’12, pages 3–14, New York, NY,

USA. ACM.

Kern, A., Hong, V., Song, J., Lipson, S. K., and Eisenberg,

D. (2018). Mental health apps in a college setting:

openness, usage, and attitudes. mHealth, 4(6).

Lin, J., Liu, B., Sadeh, N., and Hong, J. I. (2014). Model-

ing Users’ Mobile App Privacy Preferences: Restor-

ing Usability in a Sea of Permission Settings. In Us-

able Privacy and Security (SOUPS), pages 199–212,

Menlo Park, CA. USENIX Association.

Analyzing Privacy Practices of Existing mHealth Apps

569

Loughlin, K. O., Neary, M., C.Adkins, E., and M.Schueller,

S. (2019). Reviewing the data security and privacy

policies of mobile apps for depression. Internet Inter-

ventions, 15:110–115.

Martin, M. R., Melnyk, J., and Zimmerman, R. (2015). Fit-

ness Apps: Motivating Students to Move. Journal of

Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 86(6):50–

54.

McAllister, N. (2010). How to get rejected from the app

store.

Middlebury College (2019). Mental health apps.

Minen, M. T., Stieglitz, E. J., Sciortino, R., and Torous,

J. (2018). Privacy Issues in Smartphone Applica-

tions: An Analysis of Headache/Migraine Applica-

tions. Headache, 58(7).

MoodTools (2019). MoodTools - feeling sad or depressed?

Mozilla (2011). Privacy icons.

Muchagata, J. and Ferreira, A. (2018). Translating GDPR

into the mHealth Practice. pages 1–5.

Mulder, T. (2019). Health Apps, their Privacy Policies and

the GDPR. European Journal of Law and Technology,

10(1).

NY Attorney General (2017). A.G. Schneiderman An-

nounces Settlements With Three Mobile Health Ap-

plication Developers For Misleading Marketing And

Privacy Practices.

Parker, L., Halter, V., Karliychuk, T., and Grundy, Q.

(2019). How private is your mental health app data?

an empirical study of mental health app privacy poli-

cies and practices. International Journal of Law and

Psychiatry, 64:198 – 204.

Prasad, A., Sorber, J., Stablein, T., Anthony, D., and Kotz,

D. (2012). Understanding Sharing Preferences and

Behavior for mHealth Devices. In Workshop on Pri-

vacy in the Electronic Society (WPES).

Raschke, P., K

¨

upper, A., Drozd, O., and Kirrane, S. (2018).

Designing a GDPR-Compliant and Usable Privacy

Dashboard, pages 221–236. Springer International

Publishing, Cham.

Reeder, R. W., Bauer, L., Cranor, L. F., Reiter, M. K., Ba-

con, K., How, K., and Strong, H. (2008). Expandable

grids for visualizing and authoring computer security

policies. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on

Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI), pages

1473–1482, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Reetz, D. R., Bershad, C., LeViness, P., and Whitlock, M.

(2016). The Association for University and College

Counseling Center Directors Annual Survey. Techni-

cal report.

Richman, A. R., Webb, M. C., Brinkley, J., and Martin, R. J.

(2014). Sexual behaviour and interest in using a sexual

health mobile app to help improve and manage college

students’ sexual health. Sex Education, 14(3):310–

322.

Tesfay, W. B., Hofmann, P., Nakamura, T., Kiyomoto, S.,

and Serna, J. (2018). PrivacyGuide: Towards an Im-

plementation of the EU GDPR on Internet Privacy

Policy Evaluation. In Proceedings of the Fourth ACM

International Workshop on Security and Privacy An-

alytics (IWSPA), pages 15–21, New York, NY, USA.

ACM.

TTec (2019). TTec- My Benefits and App Tutorials.

Vorderer, P., Kr

¨

omer, N., and Schneider, F. M. (2016).

Permanently online – permanently connected: Explo-

rations into university students’ use of social media

and mobile smart devices. Computers in Human Be-

havior, 63:694 – 703.

Wei, X., Gomez, L., Neamtiu, I., and Faloutsos, M. (2012).

Permission evolution in the android ecosystem. In

Proceedings of the 28th Annual Computer Security

Applications Conference, ACSAC ’12, pages 31–40,

New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Youper (2019). Youper - your emotional health assistant.

Yuan, S., Ma, W., Kanthawala, S., and Peng, W. (2015).

Keep Using My Health Apps: Discover Users’ Per-

ception of Health and Fitness Apps with the UTAUT2

Model. Telemedicine journal and e-health : the of-

ficial journal of the American Telemedicine Associa-

tion, 21.

HEALTHINF 2020 - 13th International Conference on Health Informatics

570