Fog of Story: Design, Implementation and Evaluation of a

Post-processing Technique to Guide Users’ Point of View in cinematic

Virtual Reality (cVR) Experiences

Jose L. Soler-Dominguez

1 a

and Carlos Gonzalez

2 b

1

Instituto de Investigaci

´

on e Innovaci

´

on en Bioingenieria (I3B),Universitat Polit

`

ecnica de Val

`

encia,

Camino de Vera s/n, 46022, Valencia, Spain

2

ReplayX (Games and Interactive eXperiences Research Group), Florida Universitaria,

C/Rei en Jaume I s/n, 46470, Catarroja, Valencia, Spain

Keywords:

Virtual Reality, Cinematic, User Experience, Attention.

Abstract:

The impact of Virtual Reality (VR) as a narrative medium is growing quickly. Opposite to traditional films,

in cinematic VR (cVR) experiences, even when interactions are usually reduced to navigation, users are free

to move the camera at their will and could miss relevant scenes while looking at unexpected places inside

the virtual environment. Different visual cues have been developed to attract user’s attention and to make

them focus on the main narrative stream. Those visual cues usually interfere with the actual storytelling,

introducing alien elements and overloading graphically the scene. In this paper, we propose a visual post-

processing technique that applied to a VR camera will guide the user to look at where the relevant narrative

events are expected to happen using dynamic visual layers. This technique, narratively aseptic, could be

applied to different storytelling scenarios and is based on the Gaussian blur effect: the greater the angle

between the user’s vision and the area of interest is, the more blurred the content will be displayed. Moreover,

a visual guide is displayed to help the user to know at every moment the way to the area of interest. GPU

shaders are used in order to not affect the performance. Additionally, metrics will be proposed in order to

measure the effects of this technique on presence and agency, the most significant subjective parameters of

User Experience in VR.

1 INTRODUCTION

From highly interactive games to non-interactive film-

like experiences, we are witnessing an unstoppable

advance of the quality and quantity of VR content

as is shown by their presence on traditional awards

like Oscars, Baftas or Cannes’ Palmes d’Or. As hard-

ware specifications are increasing and cost is decreas-

ing, the popularity of VR is going further day by

day. Now, VR content developers count on high-

resolution, high Field of View (FoV), affordable hard-

ware like HTC Vive or Oculus Rift and also have at

their disposal a complete set of software tools like

Unity or Unreal, with specific VR features. Attend-

ing to this environment, the biggest challenge that VR

designers and developers are facing is related to the

novelty of the medium, specially when referencing to

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3819-9022

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4984-8630

non-interactive experiences. The popularity of VR as

a cinematic medium raised to its maximum with the

international premiere in 2017 of the short film Carne

y arena (virtualmente presente, f

´

ısicamente invisi-

ble)(Gonz

´

alez I

˜

n

´

arritu, 2017), a disruptive work from

the well known mexican director Alejandro Gonz

´

alez

de I

˜

narritu, being awarded with an Special Prize from

the Academy, the Special Oscar, for its novelty on im-

mersive narrative.

This cVR (along this work we will reference with

the term a wide range of experiences, from pure VR to

360°videos even though strong technical differences

exist between them) tells the misadventures of a group

of emigrants that try to enter the United States of

America through their southern frontier. In this cVR,

the spectator is on the center of the plot since VR al-

lows him/her to guide the visual storytelling since the

camera is linked to his/her gaze.

Carne y arena, attending to the director’s own

words, it is not cinema ”...because you watch a film,

Soler-Dominguez, J. and Gonzalez, C.

Fog of Story: Design, Implementation and Evaluation of a Post-processing Technique to Guide Users’ Point of View in cinematic Virtual Reality (cVR) Experiences.

DOI: 10.5220/0009087303270333

In Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2020) - Volume 1: GRAPP, pages

327-333

ISBN: 978-989-758-402-2; ISSN: 2184-4321

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

327

but you experience this. The impact the VR leaves on

people transcends the bi-dimensional or passive cin-

ema experience.”(Cort

´

es, 2017)

We suggest that is specifically this innovation, the

participation of audience on the visual narrative, the

most influencing factor over the virtual experience.

Attending to Dolan and Parets taxonomy(Dolan and

Parets, 2016), VR experiences could be classified by

two metaphysical concepts: existence and agency.

Figure 1: Dolan and Parets taxonomy.

The concept of existence aims to qualify to what

extent the viewer is part of the story, as an indepen-

dent character. On the other hand, the concept of in-

fluence reflects the viewer’s ability of making deci-

sions that affect the narrative.

If we analyze these four quadrants, the cinematic

experiences in Virtual Reality are usually classified

mostly as Active Observer (AO) and Passive Partici-

pant (PP), while Passive Observer (PO) is the one that

traditionally encompasses traditional cinema and Ac-

tive Participant (AP) groups videogames. AO implies

that the spectator is not part of the story but can make

decisions in the style of ”Choose your own adventure”

books, from an almighty point of view. PP represents

a model of experience in which the viewer is part of

the story, as a character or as an object but is never

”asked” about anything and has no ability of influ-

ence in its flow, playing a silent viewer role, a mere

receiver of the action.

These two perspectives, AO and PP, are also

named as The Witness (third person point of view, as

a spectator) and The Hero (first person point of view,

as a participant)(Nicolae, 2018).

In both cases, the element of interaction that al-

ways is opened to the user is the control of the cam-

era, the narrative point of view. This freedom comes

not only from an interest in building an immersive and

personalized narrative experience but also because of

the limitations of VR as a mean when we talk about

taking or giving control of the camera. Moving the

camera in an unilateral way (without user interven-

tion) in a VR environment could probably (it depends

on factors like genre, age or physical condition) (Far-

mani and Teather, 2018) cause Cybersickness (CS)

(LaViola Jr, 2000). This sickness condition causes

symptoms, on different degree, such as dizziness, an-

guish, nausea and malaise caused by an asynchrony

between what our senses expect to perceive and what

they are really perceiving. This is traditionally known

as sensory conflicts(Reason and Brand, 1975).

On the other hand, limiting the actions that the

user can perform, that is, that their natural interactions

have no reflection in the virtual environment, can re-

duce the sense of presence (SoP), the feeling of actu-

ally being in that ”place”. SoP represents a high level

abstraction of the subjective realism of a Virtual Real-

ity experience for a specific user in a specific moment.

Using other words, how intense is the sense of being

there (in the virtual environment). As we can read in

the founding bibliographical references of the study

of the sense of presence(Steuer, 1992; Slater, 1995),

presence constitutes the key differentiating element of

VR.

Therefore, before this transfer of camera control

by the author, aiming to deliver greater immersion and

cognitive comfort to the spectator, a challenging ques-

tion arises: How can we guide the cinematic narration

without offering a predetermined point of view?

This issue is ranked first out of the six main chal-

lenges for cVR, collected by G

¨

odde, Gabler, Sieg-

mund and Braun(G

¨

odde et al., 2018): Guiding spec-

tators’ attention to relevant narrative elements.

Along this paper different proposed solutions will

be analyzed and a novel technique will be introduced

based on findings coming from research on the fields

of cybersickness and presence. Additionally, some

metrics are proposed in order to empirically evaluate

our technique and those that will come in future.

2 CINEMATIC STORYTELLING

IN VIRTUAL REALITY

In an RV movie, it is not possible to predetermine

where the viewer will be looking. Additionally, as

mentioned in the previous section, taking control of

the camera has unwanted side effects: it breaks the

immersion and causes cybersickness. In this way, the

viewer can freely choose the direction of his gaze

and, therefore, the camera associated with his point of

view. This is possible thanks to Head Mounted Dis-

plays (HMD) or other Virtual Reality devices that act

GRAPP 2020 - 15th International Conference on Computer Graphics Theory and Applications

328

as stereoscopic glasses.

This view determines the visible portion of the

scene, the field of vision or field of view (FoV) and

is critical in the narrative experience since all points

of interest, points of interest (PoI) must be inside it.

In order to keep users’ FoV on the different PoI,

several attentional cues have been developed and

tested(Argyriou et al., 2016; G

¨

odde et al., 2018), both

into interactive or non interactive media. Including

one or more of these cues can increase the probability

of guiding the users’ FoV to each PoI:

• Face & gaze: Since faces have the ability of at-

tracting our attention, characters’ faces and their

gazes in a specific direction could be used in or-

der to guide users’ own gaze.

• Movement: Motion in a scene could recall the at-

tention of users, specially in the peripheral vision.

Additionally, the movement of the camera could

also attract the view of users, usually in the move-

ment direction.

• Sound: Another strategy to attract users’ attention

is using 3D sound. Combined with visual cues,

sound is even more effective.

• Context: This is a narrative cue. In some scenes,

the expectations of users could lead their gaze to

expected places (a door, a paper in a table, etc...)

guided by the story.

• Perspective: We can use size and position of the

assets in a scene to guide users’ attention: big-

ger and closer objects are more probable to be

seen. Also perspective is a good visual cue: paral-

lel lines are usually followed with the gaze to the

vanishing point.

These attentional cues, come form staging tech-

niques from theatre and cinema and are related to

saliency. Saliency represents the subjective percep-

tual quality that makes some elements stand out from

their neighbors in an environment and attract our at-

tention. There is a wide empirical background sup-

porting the correlation between visual attention and

saliency(Ouerhani et al., 2004; Veas et al., 2011). As

we can read in Oyekoya en al.(Oyekoya et al., 2009),

saliency could be intrinsic (related to proximity, ec-

centricity, orientation and/or velocity of items in a

scene) or extrinsic (given by the subjective interest of

the items to the user).

In our proposal, we try to attract user attention in-

creasing intrinsic saliency of the PoI of each scene.

3 PREVIOUS WORK

Even when a wide range of visual cues have been used

in order to attract users attention as we have summa-

rized into the previous section, we want to put the fo-

cus of our analysis on those that have a diegetic na-

ture. That means that are integrated into the story in a

natural way, not looking rare to viewers. In this way,

we want to highlight two examples:

• Firefly Experimental Environment: In this ex-

periment, Nielsen et al.(Nielsen et al., 2016) im-

plemented an experimental VR environment with

some relevant information showed. They evalu-

ated a method to attract users’ attention, using a

firefly to guide their gaze to PoI. They allowed

the user to freely look around the environment but

a small flying firefly offered clues as to where the

user should focus. Particularly, it would hoover

in one place when relevant information was pre-

sented in that area of the scene and then fly in front

of the user to a new position once focus should be

shifted. This diegetic method was compared with

a non diegetic one, constraining users’ ability of

interaction: forced rotation. Researchers allowed

the user to freely look around the environment, but

the orientation of the user’s virtual body would

always face in the direction where relevant story

information was presented. They measured pres-

ence with SUS questionnaire and obtained a sig-

nificant difference between the firefly condition

and the forced rotation condition. Additionally,

they counted the quantity of PoI that received the

gaze of users and here, there was no significant

difference.

Figure 2: Nielsen et al. environment with the small firefly.

• Disney’s First VR Film ”Cycles”: The short

film is directed by Disney Animation lighting

artist Jeff Gipson and it was premiered dur-

ing SIGGRAPH 2018 conference in Vancou-

ver(SIGGRAPH, 2018). This very first VR film

from the animation titan Disney, introduced a new

diegetic visual cue in order to attract viewers’

gaze to the PoI aiming to follow the intense and

emotional storytelling. This cue was based on

Fog of Story: Design, Implementation and Evaluation of a Post-processing Technique to Guide Users’ Point of View in cinematic Virtual

Reality (cVR) Experiences

329

how dreams are usually perceived: with high lev-

els of saturation where the focus is and with low

saturation on the peripherical view. The technique

was named as ”Gomez effect” honouring its cre-

ator, Jos

´

e Luis G

´

omez, a VR engineer in Disney

Animation. Its implementation was based on de-

creasing the saturation level of the scene when

users gaze is not over the designated PoI. Bigger

the distance from the gaze to the PoI, lower the

saturation level, arriving even to a complete fade

in black. No empirical validation of the efficacy

of this technique has been done.

Figure 3: Scene from Cycles, first Disney’s VR film.

Having this two implementations as a reference,

our objective is to combine the storytelling capa-

bilities (being narratively transparent) of the Gomez

effect and the empirical evaluation methods of the

Nielsen et al. firefly environment.

4 METHOD

The method proposed in this paper is based on the

use of an adaptive blur effect. With this method those

parts of the content where the user should focus are

rendered clearer than the rest of the content. More-

over its implementation takes profit of the capabili-

ties of the GPU shaders, obtaining a real-time adap-

tive blur of the scene depending on where the area of

interest is.

With this proposal the further the area of interest

is, the more blurred it will be rendered. This will

cause to the user a need of finding the area of inter-

est, where the main action of the multimedia content

is.

Blur has been chosen as key indicator from

where the action of the scene is happening attend-

ing to its navigational and perceptive neutrality as it

was stated on the experiments developed by Lang-

behn(Langbehn et al., 2016).

In subsection 4.1 our proposal is technically de-

tailed. A justification of the use of this kind of effects

for the mentioned purpose of this paper is exposed in

subsection 4.2.

4.1 Parameters and Implementation

This method uses GPU shaders in order to generate

a post-processing filter. Due to the properties of the

GPU the operations are performed in parallel, allow-

ing a real-time rendering with this dynamic effect of

the content.

The following parameters are considered in order

to decide how blurry or sharp the content is displayed:

• The α angle produced between the forward vec-

tor of the camera (

~

f ) and the directional vector

from the centre of the camera and the centre of

the area of interest (

~

d). The bigger the angle be-

tween these two vectors is, the blurrier the content

shown. This will produce to the user the need of

pay attention into the area of interest again. Fig-

ure 4 shows an example with α = 0. In contrast,

figure 5 shows an example where the user does

not directly pay attention in the area of interest.

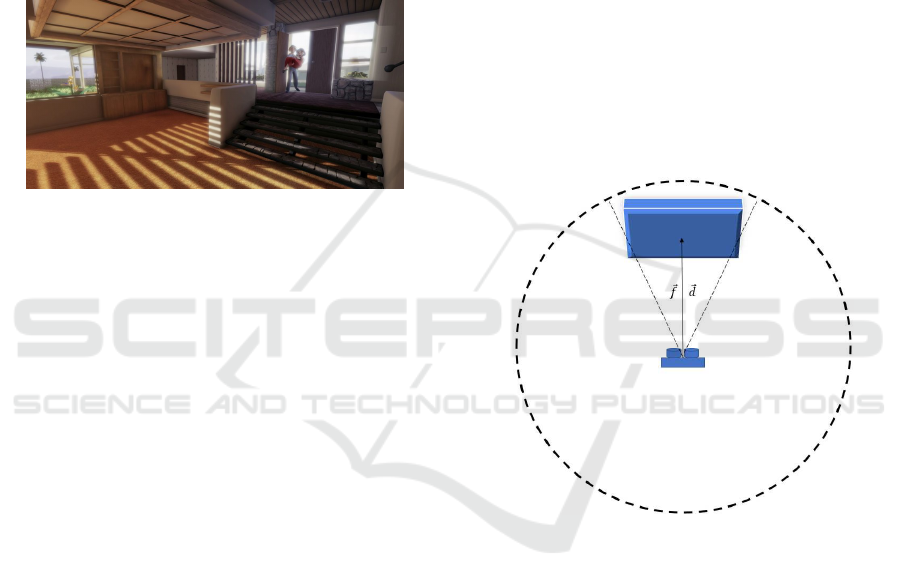

Figure 4:

~

f and

~

d vectors are the same. The user will view

a sharp content, because he/she is viewing where the main

action is produced.

• the distance from the camera to the area of inter-

est can additionally be considered. This parame-

ter will be taken into account if we want that the

size of the sharp area depends on its distance from

the user. This way the user will need to move

forward/backward in order to focus on a far/near

area. In figures 6 and 7 an example of this is

shown, with the same area of interest too far (fig-

ure 6) or near (figure 7) form the user.

Depending on these two parameters the method

will decide how the content is blurred, generating a

progressive effect when the user moves away from

the main action of the content. The method uses a

Gaussian blur effect, which can be performed in to

smoothing passes (horizontal and vertical). To do this,

GRAPP 2020 - 15th International Conference on Computer Graphics Theory and Applications

330

Figure 5:

~

f and

~

d do not match. The bigger the angle

between them is, the blurrer the content is shown.

Figure 6: The main area of interest is too fr form the user,

so it is smaller than the user’s field of view.

a GPU shader with several passes is used.In a Grab-

Pass a render-to-textured is performed and over this

texture a smoothing operation of the colors is exe-

cuted by using a Gaussian Blur effect. This can be

separated into the horizontal and vertical passes. Fi-

nally, the result is returned to the screen.

4.2 Implications over User Experience:

Metrics to Consider

In order to evaluate a technique oriented to attract

users’ attention in a cVR scene, we have to evaluate

not only its efficacy attracting but also its implications

over the sensations of presence and agency, key fac-

tors in VR user experience. Thus, we propose here

some metrics to be considered for a validation with

users. This will be the next step in this project.

Complementary to the technique explained in this

Figure 7: The main area of interest occupies the entire

user’s field of view.

paper, presence and agency have to be measure. As

other psychological states, presence can be quantified

either using an in-out approach (subjective, introspec-

tive) or an out-out approach (objective, perceived).

This last category could be splitted into two additional

subcategories: behavioral, derived from embodied re-

sponses to virtual stimulus and physiological, coming

from the sympathetic neuronal activity. In order to

complement the traditional only-subjective approach

questionnaire based, we want to measure physiolog-

ical presence using metrics like EDA (Electrodermal

Activity) or hear rate. Agency refers to ”global motor

control, including the subjective experience of action,

control,intention, motor selection and the conscious

experience of will”(Blanke and Metzinger, 2009).

Agency is present in active movements(Kilteni et al.,

2012). We propose to measure agency with subjective

questionnaires.

Additionally, cybersickness is another element to

take into consideration because any visual add on

has to pass the comfort test. Aiming to this, blur

have been chosen as the fading effect because blur-

ring slightly parts of a scene has been proved to con-

tribute to cybersickness reduction in some circum-

stances(Budhiraja et al., 2017).

Finally, aiming to determine the efficacy of this

proposed technique, a software tool has to be devel-

oped to study users’ gaze and the percentage of time

that viewers have PoI inside their FoV.

5 OUTPUTS

In this section, different examples of the Fog of Story

technique are shown.

Fog of Story: Design, Implementation and Evaluation of a Post-processing Technique to Guide Users’ Point of View in cinematic Virtual

Reality (cVR) Experiences

331

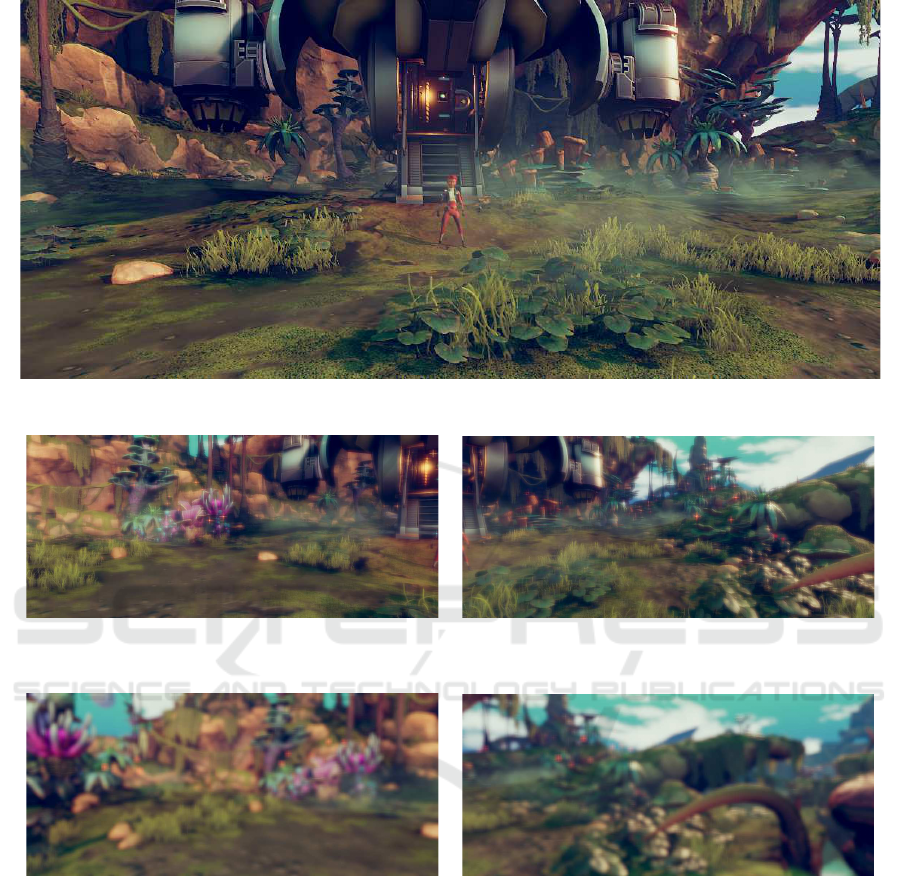

Figure 8: User’s point of view is centered in the area of interest.

~

f and

~

d match.

Figure 9: Both subfigures show the content when the user is turning 45 degrees his/her head around Y-axis. On the left the

angle α produced between

~

f and

~

d is -45 degrees. On the right the angle α produced between

~

f and

~

d is 45 degrees.

Figure 10: Both subfigures show the content when the user is turning 90 degrees his/her head around Y-axis. On the left the

angle α produced between

~

f and

~

d is -90 degrees. On the right the angle α produced between

~

f and

~

d is 90 degrees.

6 CONCLUSIONS AND FURTHER

WORK

A technique to guide users’ point of view in VR ex-

periencies has been proposed. With this method when

the viewer is far from the area of interest the content

is showed blur. Thus, in order to guide the user to find

the area of interest we propose a helper in the screen.

This helper could be a visual effect that helps the user

in two different ways: the direction and the distance

from the area of interest. This helper should be a non-

intrusive mark or virtual content without covering the

content. Additionally, some metrics have been pro-

posed in order to study the efficacy and suitability

of this technique. Measuring cybersickness, sense of

presence, sense of agency and the percentage of time

that viewers have they gaze on PoI will ensure an em-

pirical evaluation of this implementation that could be

used in order to improve storytelling in cinematic Vir-

tual Reality experiences. This validation with users is

the next step in this project.

GRAPP 2020 - 15th International Conference on Computer Graphics Theory and Applications

332

REFERENCES

Argyriou, L., Economou, D., Bouki, V., and Doumanis, I.

(2016). Engaging immersive video consumers: Chal-

lenges regarding 360-degree gamified video applica-

tions. In 2016 15th International Conference on Ubiq-

uitous Computing and Communications and 2016 In-

ternational Symposium on Cyberspace and Security

(IUCC-CSS), pages 145–152. IEEE.

Blanke, O. and Metzinger, T. (2009). Full-body illusions

and minimal phenomenal selfhood. Trends in cogni-

tive sciences, 13(1):7–13.

Budhiraja, P., Miller, M. R., Modi, A. K., and Forsyth, D.

(2017). Rotation blurring: use of artificial blurring

to reduce cybersickness in virtual reality first person

shooters. arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.02599.

Cort

´

es, J. (2017). El cine, ante su gran revoluci

´

on gracias a

la realidad virtual.

Dolan, D. and Parets, M. (2016). Redefining the axiom of

story: The vr and 360 video complex. Tech Crunch.

Farmani, Y. and Teather, R. J. (2018). Viewpoint snapping

to reduce cybersickness in virtual reality.

G

¨

odde, M., Gabler, F., Siegmund, D., and Braun, A. (2018).

Cinematic narration in vr–rethinking film conventions

for 360 degrees. In International Conference on Vir-

tual, Augmented and Mixed Reality, pages 184–201.

Springer.

Gonz

´

alez I

˜

n

´

arritu, A. (2017). Carne y arena.

Kilteni, K., Groten, R., and Slater, M. (2012). The sense of

embodiment in virtual reality. Presence: Teleopera-

tors and Virtual Environments, 21(4):373–387.

Langbehn, E., Raupp, T., Bruder, G., Steinicke, F., Bolte,

B., and Lappe, M. (2016). Visual blur in immersive

virtual environments: does depth of field or motion

blur affect distance and speed estimation? In Proceed-

ings of the 22nd ACM Conference on Virtual Reality

Software and Technology, pages 241–250. ACM.

LaViola Jr, J. J. (2000). A discussion of cybersickness

in virtual environments. ACM SIGCHI Bulletin,

32(1):47–56.

Nicolae, D. F. (2018). Spectator perspectives in virtual real-

ity cinematography. the witness, the hero and the im-

personator. Ekphrasis (2067-631X), 20(2).

Nielsen, L. T., Møller, M. B., Hartmeyer, S. D., Ljung, T.,

Nilsson, N. C., Nordahl, R., and Serafin, S. (2016).

Missing the point: an exploration of how to guide

users’ attention during cinematic virtual reality. In

Proceedings of the 22nd ACM Conference on Vir-

tual Reality Software and Technology, pages 229–232.

ACM.

Ouerhani, N., Von Wartburg, R., Hugli, H., and M

¨

uri, R.

(2004). Empirical validation of the saliency-based

model of visual attention. ELCVIA: electronic letters

on computer vision and image analysis, 3(1):13–24.

Oyekoya, O., Steptoe, W., and Steed, A. (2009). A saliency-

based method of simulating visual attention in vir-

tual scenes. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM Sym-

posium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology,

pages 199–206. ACM.

Reason, J. T. and Brand, J. J. (1975). Motion sickness. Aca-

demic press.

SIGGRAPH (2018). Disney animation to premiere first vr

short at siggraph 2018.

Slater, M. (1995). Taking Steps: The Influence of a Walking

Technique on Presence in Virtual Reality. ACM Trans-

actions on Computer-Human Interaction, 2(3):201–

219.

Steuer, J. (1992). Defining virtual reality: Dimensions de-

termining telepresence. Journal of communication,

42(4):73–93.

Veas, E. E., Mendez, E., Feiner, S. K., and Schmalstieg, D.

(2011). Directing attention and influencing memory

with visual saliency modulation. In Proceedings of the

SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing

Systems, pages 1471–1480. ACM.

Fog of Story: Design, Implementation and Evaluation of a Post-processing Technique to Guide Users’ Point of View in cinematic Virtual

Reality (cVR) Experiences

333