Memorable and Emotional Media Moments: Reminding Yourself of

the Good Things!

Teresa Chambel and Pedro Carvalho

LASIGE, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal

Keywords: Interactive Media Content, Wellbeing, Emotions, Positive Computing, Self-assessment, Sensors,

Multimodality, Happiness Jar, Personal Journal.

Abstract: Experiencing digital media content is among the most accessible and beloved recreational activities people

indulge in. It can promote learning and creative thinking, as well as being an important source of

entertainment, with a great impact in our emotions. In particular, it has the power to foster positive emotions

and attitudes, to regulate or enhance our mood, contributing to our general sense of wellbeing and quality of

life. This paper discusses and explores the potential of media and how it can be addressed to create a tool to

help individuals become more aware of their emotions and promote their psychological wellbeing. It

discusses main motivation and background and presents EmoJar, an interactive web application designed

and developed to allow users to collect and relive media that have significant impact and remind them of the

good things they experience along time in their lives. EmoJar is based on the Happiness Jar concept,

enriched here with media and its emotional impact, as an extension to Media4WellBeing, aligning with the

goals and approaches of Positive Psychology and Positive Computing. User evaluation results were very

encouraging in terms of perceived usefulness, usability and user experience. Future work will lead us further

in the aim to provide a useful and interesting digital experience that further supports users in their journey of

personal awareness and development.

1 INTRODUCTION

Accessing and consuming digital media content that

we treasure has never been so easy and quick to do.

Watching videos (from short clips, to full movies),

listening to audio (like podcasts, audio books, or

music), surveying images (like memes and photo-

graphs of awe-inspiring landscapes), and reading

text (factual, or literary) are among the most

accessible and beloved recreational activities.

Besides promoting learning, improving cognition,

endorsing creative thinking, aiding in productivity,

and generally being great sources of entertainment,

media has a great impact in our emotions (Oliveira

et al., 2013). In particular, it has the power to foster

positive emotions and attitudes, to regulate or

enhance our mood, contributing to our general sense

of wellbeing and quality of life (Bernardino et al.,

2016; Kok et al., 2013).

In this paper, we review main concepts and

related work as a background to help understand this

power, and how we can support users becoming

more aware, and regulating their emotions with

media through the EmoJar. We describe this

interactive web application designed and developed

as an extension to Media4WellBeing (Bernardino et

al., 2016) based on the Happiness Jar concept, to

collect and remind users of the good things they

experience along time, enriched with emotionally

impactful and memorable media, and supported by

sensors and self-report. It aligns with the approaches

of Positive Psychology and Positive Computing with

the ultimate goal of contributing to individuals’

psychological wellbeing and development. The

evaluation allowed validating the concept and the

design options; and the results revealed users’

interest and appreciation contributing to identify and

confirm preferred features, usability aspects and

future directions.

2 BACKGROUND

We present main concepts, goals and approaches

relevant in media support for wellbeing, as a back-

ground and context for our work and contributions.

86

Chambel, T. and Carvalho, P.

Memorable and Emotional Media Moments: Reminding Yourself of the Good Things!.

DOI: 10.5220/0009178300860098

In Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2020) - Volume 2: HUCAPP, pages

86-98

ISBN: 978-989-758-402-2; ISSN: 2184-4321

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

2.1 Wellbeing, Positive Psychology and

Positive Computing

According to Dodge et al. (2012), coming up with a

single definition of wellbeing can be quite

challenging. But overall, one can say that wellbeing

is having the physical, psychological and social

resources necessary to meet a particular physical,

psychological or social challenge.

Positive Psychology focuses on the psycholo-

gical component of wellbeing (Seligman et al.,

2005). Established by Seligman in 1998 out of

frustration with Psychology’s narrow focus on

negative aspects and disfunctions, requiring to be

solved and cured. This newer perspective posits that

individuals should learn to embrace a more positive

perspective, which could lead to significant shifts

with impact on wellbeing and happiness. In one of

his studies (Seligman et al., 2005) on gratitude,

participants wrote down 3 things that went well each

day, and why, every night, for one week. This

greatly and lastingly contributed to individuals’

psychological wellbeing, suggesting that 1) the more

we shift our focus away from negativity, the happier

we will be, and that 2) reflecting on the good things

that happen to us contributes to our psychological

wellbeing. The EmoJar intends to support this

attitude with digital media.

Positive Computing is a related field, founded by

Calvo and Peters in 2014 (Calvo and Peters, 2014),

centered upon the design and development of

technology that supports psychological wellbeing

and human potential. It posits 3 approaches: 1) the

preventative approach, where technology is redesi-

gned to address or prevent detriments to wellbeing;

2) the active approach, where it is designed to

consider and promote the wellbeing of individuals

(the one adopted in our work); and 3) the dedicated

approach, where technology is created and totally

dedicated to promoting wellbeing.

2.2 The Happiness Jar

The Happiness Jar concept is about giving its users

the chance to collect and remind themselves of all

the good things that come out in their life (e.g. every

day for a year). The traditional ones are based on a

physical jar (often made of glass with a lid) where

individuals place small papers scribbled with things

that made them happy, proud, or grateful, to be read

on special occasions (e.g., New Year or birthday), or

when its owners feel like they need to be reminded

of the good things in their lives. In spite of its

simplicity, the idea behind this tool is quite power-

ful, aligning with Seligman’s (2005) and related

research on wellbeing and positive emotions. The

Happiness Jar not only serves as a great time capsule

of life’s best, but may also promote individuals’

psychological wellbeing. However, the traditional

analog physical jar is limited in its ability to support

users, in terms of flexibility, portability, media

types, organization, search, access, and emotional

awareness.

In digital apps like HappiJar (Cooper, 2014), Jar

of Awesome (JarAwe-ref), and The Happiness Jar

(TheHappiJar-ref), users can write down and collect

happy moments in a digital jar, and optionally

associate photos or music to them. Happiness Jar

and Jar of Awesome allow categorization of happy

moments. Jar of Awesome allows access in a

timeline, while HappiJar supports shared jars and the

possibility to shake to get a random jar entry. Not in

the form of jars: HappyFeed (HappyFeed-ref) and

Applied Happiness (2016) apps are daily journals to

register positive moments, thoughts or memories

with optional photos and locations. These projects

allow users to register what makes them happy, but

do not explore the power of media to do so, media

being an optional add-on. On the other hand in

approaches like Cove (Humane, 2015-19), media is

central but from the perspective of the creator; users

create small loops of music to help them express

how they feel in a safe, positive environment, and it

does not also support detecting user’s emotions.

2.3 Media Impact on Emotions and

Psychological Wellbeing

Media consumption (of video, audio, images, and

text) takes a significant share of our waking hours,

making media impact concerns increasingly rele-

vant. Most research has focused on detrimental

effects but, more recently, research has started to

explore potential benefits. It can e.g. provide relief

from stress and daily hassles, or facilitate recovery

after a long day (Reinecke, 2011). It can also: have

us reflect upon moral virtues and the purpose of life;

impel us to be more altruistic, empathetic, compas-

sionate, tolerant, and let go of feelings of resent-

ment; make us experience a range of emotions; and

help us be more appreciative of our life, and grateful

for the good things in it.

In spite of the emotional impact of media and its

potential to foster improved psychological well-

being, most work does not allow users to access,

visualize, explore, save and later relive media based

on this impact (Oliveira et al., 2013; Bernardino et

al., 2016). In our own work: in iFelt (Oliveira et al.,

Memorable and Emotional Media Moments: Reminding Yourself of the Good Things!

87

2013), users were given the ability to access,

explore, and visualize videos classified according to

the emotions felt (using biosensors and 5 out of 6

basic emotions by Ekman (1992)); MovieClouds

(Chambel et al., 2013) allowed to access, explore

and watch movies based on their content, mainly

audio and subtitles, and with a focus on emotions

expressed in the subtitles, in the mood of the music,

and felt by the users, like in X; in Media4WellBeing

(Bernardino et al., 2016) we took a step further to

include other media, a richer emotional model, and

the sense of wellbeing. More recently, it also

allowed users to add personal tags and self-

assessment in meditative states (Martins et al.,

2018); but not emotions, and no information about

why media made them experience those emotions or

improved their wellbeing, for increased awareness

and to recall in future accesses - like we now

included in EmoJar, to combine the ability to

consume media based on the emotional impact with

the strength of journals and jars.

3 EMOJAR

EmoJar is an interactive media application that is

based on the concept of the Happiness Jar, where

individuals typically collect and recall in small

papers things that made them happy, proud or

grateful for, now enriched with media and their

emotional impact. It has been designed and develo-

ped to let its users save, access, explore, and relive

media that was impactful and that they believe to

have positively contributed to their psychological

wellbeing. Users can rely on the emotional impact

based on biosensors and self-assessment, by

registering their personal perception and reflections

about the impact of the media and the associated

memories making it worth keeping in the jar, to be

relived. What follows is a presentation of EmoJar

characteristics and features, namely: its emotion

model and detection methods, how to collect and

relive media, how to filter the EmoJar for particular

entries, how one may interact with it, and what one

may learn from using it.

3.1 Emotions: Power, Models and

Detection

Emotions can be classified as positive or negative.

Positive emotions have been shown to foster

improved health, coping ability, physical and

psychological wellbeing, social relationships, work

life, and even income. They also enhance cognitive

capacities and creative problem solving; whereas

negative emotions, which narrow the individual’s

repertoire of thought and action, have a valuable

survival strategy, but have been shown to be

detrimental to physical and psychological health and

many other aspects of life (Chambel et al., 2011;

Kok et al., 2013). Emotion valence (polarity: posi-

tive-negative) is one important dimension, and along

with arousal (intensity) define the Dimensional

Model of emotions (Russell, 1980) in a spatial 2D

circumplex. The Categorical Model defines emo-

tions as discrete states, and can be represented in the

dimensional model.

In (Bernardino et al., 2016), we present more

details about models of emotions and wellbeing, and

describe the model we adopted in Media4Well-

Being, the same now in the EmoJar. It extends basic

emotions from Ekman (1992) and Plutchik’s (1980)

(adopting his color choices), aiming at: 1) emotional

richness; 2) covering positive emotions associated

with media and wellbeing (e.g. Ekman only has one

positive emotion, insufficient in this context); and 3)

being simple enough to enable an automatic

identification of emotions, based on valence and

arousal.

Figure 1: Emotion color wheels in EmoJar.

Figs. 1 and 3 present the adopted model with

categorical emotions placed around Russel’s circum-

plex as a wheel of emotions. Fig.1 presents 3

versions. The first one adopts emotion colors from

Plutchik’s (1980), but since these models have

different dimensions, the colors do not make as

harmonious smooth transitions around the wheel as

in Plutchik’s. The second version adopts Plutchick’s

color wheel mapping to the emotions on our wheel,

with an harmonious color sequence; and the third

version adopts Geneva wheel (Sacharin et al., 2012),

also with smooth transitions but with dimensions

closer to our own. Although some color-emotion

mappings are more common than others, these tend

to be subjective and also dependent on culture.

Different options in EmoJar allow for flexible and

personalized settings. Users may choose their

favorite anytime (clicking on the current wheel on

the right top corner, e.g. Fig1) and the interface

adjusts to the new color mapping. This was

appreciated by the users in the evaluation, and even,

HUCAPP 2020 - 4th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

88

by some, the possibility of having users personali-

zing or painting their own wheels - being considered

for future work.

One of the challenges in these approaches refers

to how wellbeing and emotions can be measured,

besides from self-assessment. To a greater or lesser

extent, they tend to bring about physiological

changes, which can be detected and processed, using

sensors. We are using BITalino (for ECG and EDA)

and MUSE (for EEG) to detect emotions based on

valence and arousal, complemented with meditative

states (Bernardino et al., 2016; Martins et al., 2018).

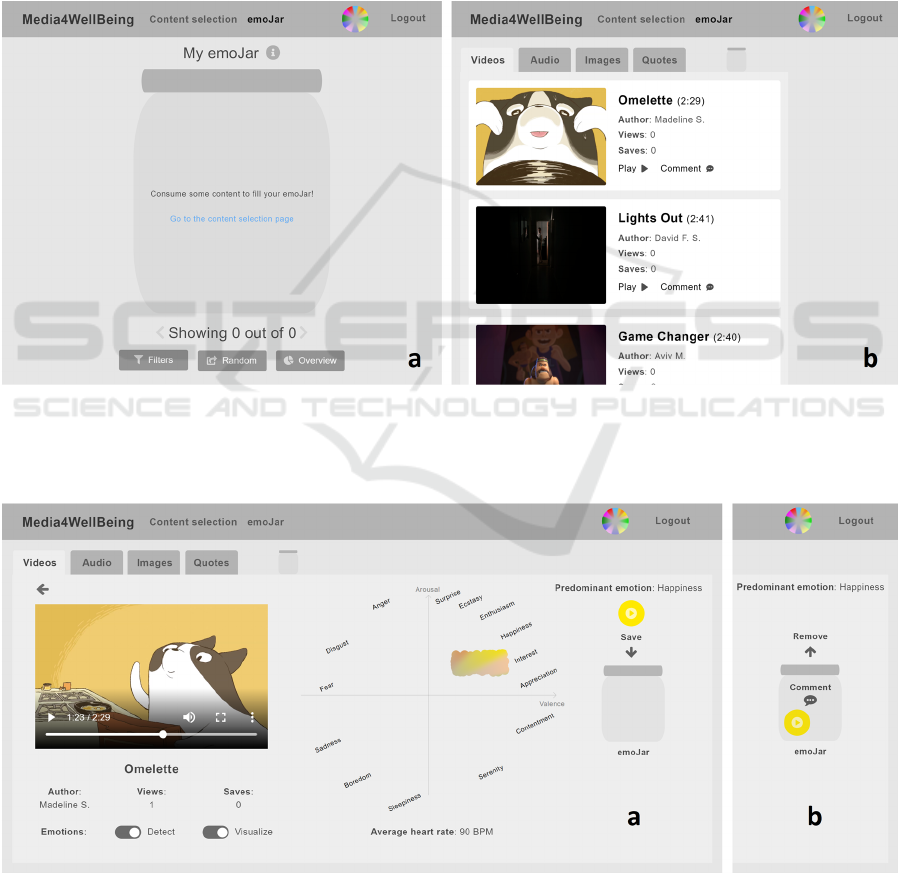

3.2 Collecting and Reliving Media

Users can collect media while browsing and

accessing it. If the EmoJar is accessed in its initial

empty state (Fig.2a), it prompts users to consume

some media in the content selection page (Fig.2).

Users may save content in the jar without consuming

it, pressing the icon to the right of its title (Fig.2b).

But at least they need to register what the content

means to them, in the “paper”/entry they save in the

jar, when there is no emotional information detected.

Fig.3 shows the case when there is an automatic

Figure. 2: Jar initial state - empty. (a) EmoJar invites users to consume content on the content selection page; (b) users can

access content items (e.g. videos) and play (Play icon) or save them in the jar (Comment icon); they can check how many

times this content was Viewed and Saved, the latter useful in situations when the same content was meaningful, possibly

with different emotions, and it is relevant to save it. A new jar entry is created for each time it is saved.

Figure 3: Content consumption and emotional evaluation. a) Each content (left) and its emotional evaluation (center, in

emoPaint view here) is represented by a circle (right) with dominant emotion color (detected or self-reported), with an icon

representing media type: users may comment to add self-assessment (Fig.3-Fig.5); and a/b) Save/Remove it as a jar entry.

Memorable and Emotional Media Moments: Reminding Yourself of the Good Things!

89

Figure 4: Entry in detail - content and detected emotions

(above); below: 1) level of agreement with detected

emotions; 2) self-reported emotions; 3) why user felt this

emotions; and 4) what user thinks about the video, what

makes it memorable.

Figure 5: Entry preview in the jar (left) before opening it

(right), when open is similar to Fig. 4, not editable in

viewing mode.

detection while consuming a video. Users get emo-

tional feedback (results provided by Media4Well-

Being with physiological sensors) that can be pre-

sented in the form of a painting in the emotion wheel

(emoPaint), a tag cloud (emoCloud), or a chart

(emoChart) (Bernardino et al., 2016), synchronized

with the video as it is being watched, or afterwards

(avoiding interfering with the watching) by

animation or final state. The users then have the

option to save (or remove) the selected content and

its emotional impact to their jar (Fig.3a/b), and to

further complement with information by self-

assessment (Fig.3b-Fig.4, and Fig.5 (right)).

In the paper/entry saved, besides the content that

provides context, and the detected emotions (in

emoPaint representation in Fig.4), users may

comment and report their self-assessment, by: 1)

rating how much they agree with the automatic

emotion recognition; 2) can draw their personal

perspective of how they felt; 3) comment on the felt

emotions; and 4) add their thoughts and perceptions

about the content, its emotional impact and the

associated memories making it worth keeping in the

jar. In Fig.4, the user agreed with the emotions

identified by Media4WellBeing (1), but there were

others (Surprise and Appreciation) that were

added/painted (2), explaining why these were felt

emotions (3), and commenting on how this video

was important and what made it memorable (4).

Once content has been consumed and saved or

commented upon, an EmoJar entry in the shape of a

circle (representing a crumpled paper, Fig.2) is

created, and can be retrieved and relived later on by

the user. The entry’s color is defined by the predo-

minantly felt emotion recognized by Media4Well-

Being or the users (in self assessment), the center

icon representing content type.

HUCAPP 2020 - 4th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

90

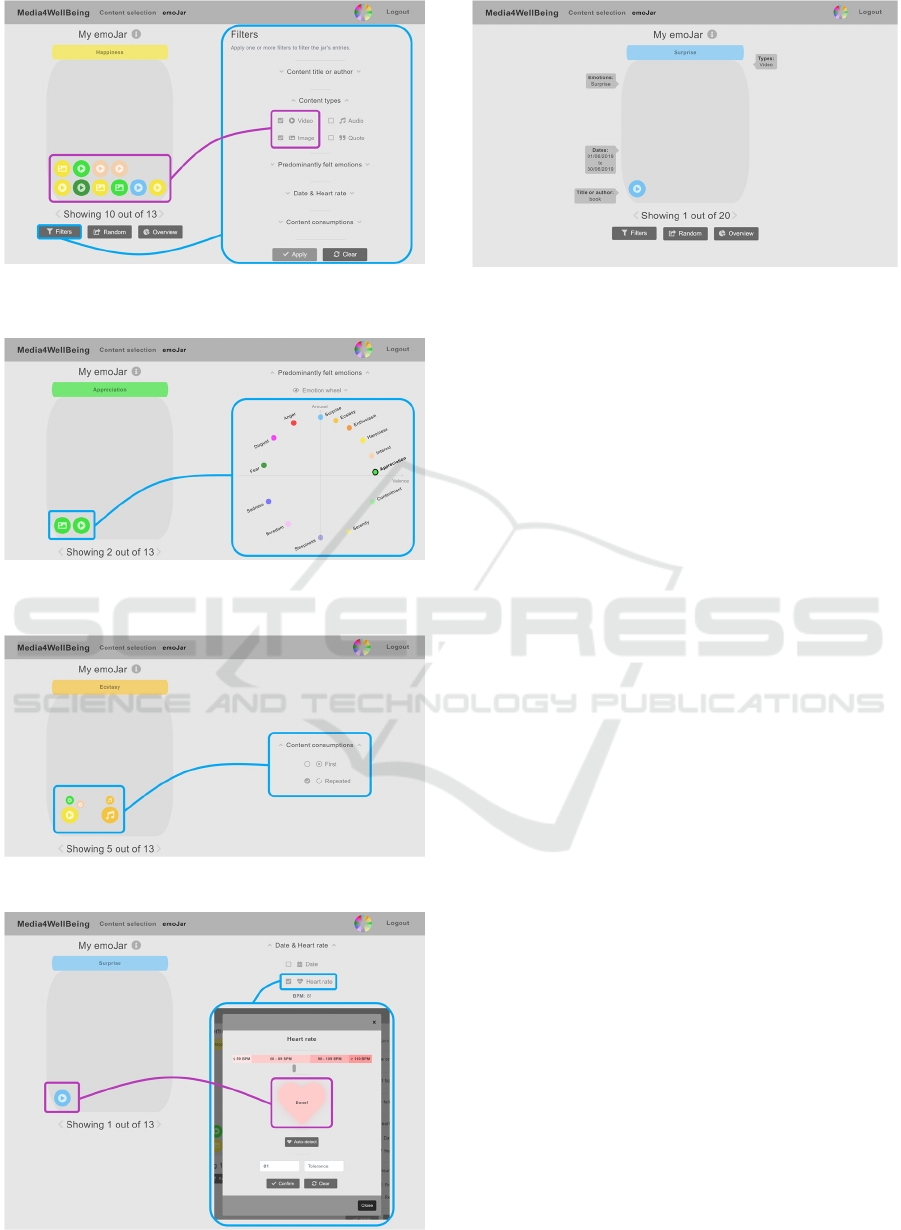

Figure 6: Jar filter in EmoJar. Filters (right); jar state after

applying content type filter for videos and images (left).

Figure 7: Jar state after dominant emotion filter for

Appreciation.

Figure 8: Filter for content with repeated saves.

Figure 9: Applying average heart rate filter.

Figure 10: Tooltips pop-up with filter options when filters

close.

This content entry, and whether it has associated

results/comments can be previewed on hover, and

reviewed/relived upon clicking (Fig.5). By way of

its color and label, the jar’s lid reflects which

emotion is more predominant in the jar.

3.3 Jar Filtering in Different

Perspectives

Along time, users’ jar starts to fill up and users may

also have in mind different properties to look for,

bringing about the need for filters, to allow users to

find and review contents that contributed to they

wellbeing in different ways (Fig.6-10). As presented

in Fig. 6, selecting the “Filters” option will show all

the filters in an overview with parameters hidden.

These will be revealed for each filter, when

selected: content type in the example, with video and

image selected in the check boxes. Figs. 7-10

exemplify other filters, with chosen parameters and

results. Currently, it is possible to filter entries by:

words in the title or the author; content type (video,

audio, image or quote); predominantly felt emotion

(selected in the emotion wheel in Fig.7); with or

without biosensor or self-assessment results

associated; first entry of all the content saved

(“First”) or all the entries of the same content that

were consumed and saved/collected more than once

(“Repeated”) because it made sense to save at

different times, possibly with a different emotional

impact and new comments (Fig. 8); date or time

interval when entries were collected (using a

calendar); and average heart rate (Fig. 9).

These filters can be selected separately or

combined. The jar then only shows matching entries

(Figs. 6-10). At any time, the lid of the jar adopts the

color and name of the dominant emotion in the set of

entries satisfying the filtering criteria.

Memorable and Emotional Media Moments: Reminding Yourself of the Good Things!

91

3.4 Multimodal Interaction

Multimodal interaction is being adopted for

flexibility, accessibility and its potential to increase

engagement and immersion (Serra et al., 2014) when

interacting with the jar and its contents.

Concerning heart rate filtering (Fig.9), we

designed and developed different modalities for

inserting a value (with a tolerance within its

vicinity): 1) text entry; 2) selecting a value on a

scale (a bar with different colors highlighting typical

values); 3) tapping the heart icon through mouse,

keyboard, or touch screen (as feedback the heart

updates the numeric value, and changes color,

according to the colored scale above); or 4) auto-

detecting users heartrate with sensor (placing finger

over the video camera on the mobile phone, it

measures image brightness variability, in accordance

with heart rate and subsequent blood pumping

reaching the finger). For their current heart rate, in

the absence of a sensor, users may e.g. press the

carotid artery to sense and try to tap the heart in the

interface (3) with the same frequency.

We also designed a feedback based on user’s

current heartbeat, e.g. in the rhythm of the emoPaint

output, or the rhythm of background color change

between two colors, or yet through haptic smart-

phone vibration, while a video is being watched, and

plan to consider other modalities in the future.

Janssen et. al. (2010) concluded that heartbeat

perception influences social behavior, promoting the

sense of closeness, as an intimate cue in immersive

virtual environments. Heartbeat communication was

also seen as a promising way to improve emotion

recognition with potential benefits on social

connectedness, health, and wellbeing. Their study

was done in the context of interpersonal

communication; we hypothesize that it can also be

beneficial on our own, for emotional self-awareness

and regulation.

Figure 11: Get random jar entry: button (left), shaking

(right).

Another feature with multimodality is available

when the user desires to get a random EmoJar entry

(Fig.11): by pressing the “Random” button, or by

shaking the mobile device in the way suggested by

the “Pick random” button’s icon, which resembles a

mobile device being shaken. Doing so gets one

random EmoJar entry out of the jar, introducing a

flavor of serendipity (Chambel, 2011) creating the

chance to find a relevant unexpected content. Then it

is up to the user to preview and relive it (by clicking

on it).

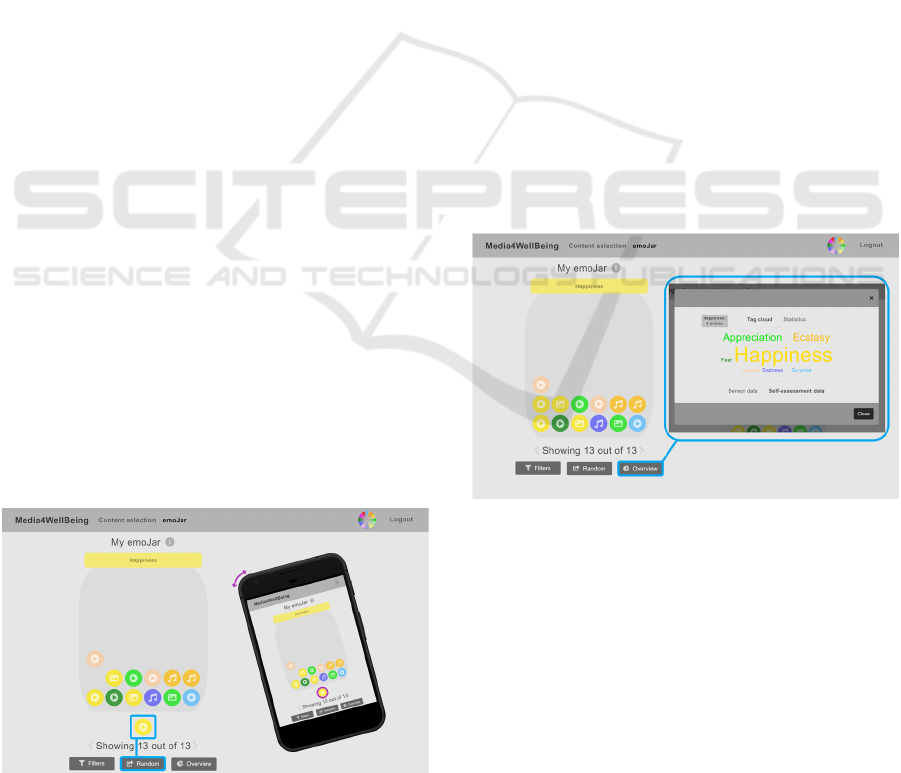

3.5 Overviews for Self-awareness and

Learning

Users can get information about their media

consumption habits in EmoJar. This information can

add to the support of self-awareness that our

approach emphasizes, in a perspective of self-

development, along time. Users may, e.g., find out

what content types they consume the most, as well

as what emotions they have felt so far or throughout

time according to Media4WellBeing’s emotion reco-

gnition system and user self-assessment. Fig. 12

highlights a tagcloud view representing frequency of

dominant emotions in the jar content. Happiness is

more frequent in this example, being dominant in 4

of the 13 jar entries.

Figure 12: Overview of dominant felt emotions in jar’s

content. A tag cloud is presented, with “Happiness” as

most frequent one.

4 USER EVALUATION

The primary objective of this user evaluation was to

assess EmoJar usability and user experience through

perceived usefulness, satisfaction, and ease of use of

its functionalities. We also wanted to know the

users’ opinions, comments, and suggestions on the

features, interface and representations.

HUCAPP 2020 - 4th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

92

4.1 Methodology

This evaluation consisted of semi-structured

interviews and user observation while users carried

out previously defined tasks to test the different

features. First, the evaluation and system’s purpose

were explained, followed by a selection of

demographic questions to characterize the users,

who then performed the tasks, in the order listed in

Table 1. For each task, we 1) observed and noted

success, completion speed, errors and hesitations; 2)

asked users to rate the perceived usefulness,

satisfaction, and ease of use (based on USE (Lund,

2001)) of the tasks’ functionalities and

representations on a 5-point Likert scale; and 3)

gathered qualitative feedback as users’ comments

and suggestions. All tasks were executed on a

camera-equipped laptop, then on a smartphone, to 1)

know the impact of the screen size; and to 2) assess

the mobile-exclusive features (the vibration

feedback on content reproduction, and the “shake to

extract a random entry”).

In the end, users were asked to 1) make an

overall assessment of the system in terms of its

design, usefulness, satisfaction, ease of use, and

usability (SUS (Brooke, 1996)); 2) mention the

features and characteristics that positively stood out

to them; 3) make their final comments and

suggestions on what they would like to see improved

or added in the future; and 4) characterize the system

by selecting pre-defined terms that adequately

reflected its appeal and overall ergonomic and

hedonic qualities (Hassenzahl et al., 2000).

4.2 Participants

This evaluation had 10 participants, 5 male, 5 female

22-57 years old (Mean (M) 31.1, Std.Dev (SD)

12.6), all with higher education (1 PhD, 3 MSc, 6

BSc) in different areas (1 systems, 1 telecom and 1

electrical engineers, 1 highschool teacher, 1 human

resources manager, 1 multimedia designer, and 4 IT

graduates pursuing an MSc in Informatics),

moderate to high levels of digital literacy, and

having their first contact with EmoJar.

1) Digital media content impact: all 10

participants strongly agreed (5, in 1-5 Likert scale)

that digital content can make individuals experience

emotions; has the ability to evoke memories; and

that the experienced emotions can be a result of

these evoked memories .

2) Access digital content: using smartphone (10

every day); computer (2 every day (ed), 4 more than

1/week, 2 1/week, and 2 (occ)asionally); and tablet

(2 occ). Platforms: YouTube (5 ed, 3 >1/week, 2

occ); Netflix (4 ed, 3 >1/week, 2 occ); Spotify (2 ed,

6 >1/week); Instagram (4 ed); Pinterest (2 >1/week,

2 occ); Vimeo (4 occ), TED.com (3 occ); Crunchy-

roll (1>1/week); and Flickr (1 occ).

3) Motivation to access (1-5:“Strongly

disagree”-“Strongly agree”): be entertained (M:4.8,

SD: 0.4); feel more relaxed (M:4.2, SD:0.6); be

informed (M:3.5, SD:0.5); feel good (M:3.4,

SD:0.5); feel motivated (M:2.9, SD:1.1); be able to

deal with difficult situations (M:2.9, SD:1.1); feel

better about themselves (M:2.6, SD:1.1); feel more

creative (M:2.3, SD:1.2); be able to improve as a

person (M:2.3, SD:1.2); be able to work better

(M:2.2, SD:1.3); better know themselves (M:1.6,

SD:0.7); and positively influence others (M:1.3,

SD:0.5).

4) How and why digital content is saved: 9 save

in browser’s favorites; 6 in the playlist of the

platform used (e.g., YouTube, Spotify), and 5

download and store on computer (3) and smartphone

(2). They save it to: create a collection of contents

they enjoy (M:4.4, SD:0.5); consume later on

(M:4.1, SD:0.3); share later on (M:3.2, SD:0.9);

because they symbolize a moment of their lives

(M:3, SD: 0.9); to later change their mood (M:2.4,

SD:0.9); to reminisce about them later on (M:1.5,

SD:0.7).

5) Happiness Jar, related apps, and

physiological sensors: 6 of 10 participants are used

to recording and describing their lives’ most

memorable moments, associated thoughts and

emotions: on social media (5); journal (3);

smartphones’ note-taking apps (2); and on the back

of Polaroid photos (1). None of the participants were

familiar with the Happiness Jar concept, never

created or used one, nor did they use an app or

platform based on or related to it. On the other hand,

4 users had previous experience with physiological

sensors, 2 in academic contexts (EEG, ECG, and

BVP sensors), and 2 in personal use (at-home ECG).

The other 6 had never used but were interested in

doing so.

4.3 Results

In this section, we present the evaluation’s results.

Overall, users have completed all tasks quickly and

without much hesitation, and they generally enjoyed

their time and experience with the system. More

detailed results are presented in the tables and

commented in the text along with user suggestions.

Memorable and Emotional Media Moments: Reminding Yourself of the Good Things!

93

4.3.1 Content Selection

Task 1: “Gauge the jar’s state in content selection

page.” (initially empty). 6 users quickly found and

made use of the small jar representation to correctly

assess it was empty. The other 4 took some time to

find it, but as soon as they did, they easily deter-

mined its state. They suggested to add a label, which

we readily did. USE results were quite positive

(U:4.1, S:4.0, E:5.0). After tasks 4 and 5, users

rechecked the new state of the jar (with an entry in

the jar), and some found this feature “useful”,

“delightful”, and “amusing”.

4.3.2 Content Reproduction

Task 2: “Select, consume, and save the video

‘Omelette’”. In Media4WellBeing (Bernardino et

al., 2016) we had already evaluated the “emoPaint”

view, here we focused on the new features, namely:

2.1) interface’s background pulsing to the

rhythm of one’s heartbeat (U:3.3,S:3.3,E:4.1). 3

users preferred “on” (to know their heart rate was

being estimated), 2 users preferred “off” (finding it

distracting), and 5 users were “indifferent” (subtle

enough to go unnoticed when focusing on the

content);

2.2) feeling heartbeat through smartphone

vibration (U:3.5, S:3.8, E:5.0). 3 users would rather

see “on” (found it “uniquely different” and “a very

real way of communicating one’s heart rate”), 2

preferred “off” (“distracting” and “potentially

irritating” in long-term), and 5 were “indifferent”

(subtle enough to not disturb and go unnoticed after

a while);

2.3) having “emoPaint” be painted to the rhythm

of heartbeat (U:3.5, S:3.4, E:4.0). 3 users found

“curious” and “interesting”, and we felt that, if not

for smartphone’s vibration along with the painting of

a dot, this feature could go a little “unnoticed”;

2.4) having an “average heart rate” text shown in

real-time (U:3.8, S:3.8, E:5.0), which users found

“interesting” and “informative”, and allowed

awareness of how their bodies responded to the

content they found emotionally uplifting, sad, or

even scary. After task 7.2, one user suggested a heart

rate line graph drawn along content’s consumption;

2.5) having “Predominant felt emotion” in text

(U:4.8, S:4.5, E:5.0). All users appreciated, some

believed to be “absolutely essential” to understand

which emotion was predominant when more than

one was painted in an identical way;

2.6) being able to save the consumed content on

the jar (U:4.1, S:4.1, E:4.5). Users found easy to do

and communicated clearly (when saved or not).

4.3.3 Self-assessment

Task 3: “Comment on the consumed video.” to get

their input on some of this page’s features, like:

3.1) the ability to rate how much they agree with the

sensor-recognized emotions (U: 5.0, S: 4.4, E: 5.0).

Table 1: USE evaluation of EmoJar (Scale:1-5: lowest-

highest); M=Mean; SD=Std. Deviation).

Task U

S E

T# Feature

M SD M SD M SD

Content Selection: (M)

4.1 0.7 4.0 0.5 5.0 0.0

1 small jar representation 4.1 0.7 4.0 0.5 5.0 0.0

Content Reproduction(M)

3.8 0.6 3.8 0.7 4.6 0.4

2.1 heartbeat: background 3.3 0.5 3.3 0.5 4.1 0.9

2.2 heartbeat: phone vibration 3.5 0.5 3.8 0.6 5.0 0.0

2.3 heartbeat: emoPaint rhythm 3.5 0.5 3.4 0.5 4.0 0.9

2.4 heartbeat: avg in text field 3.8 0.9 3.8 0.9 5.0 0.0

2.5 predom. emotion: text field 4.8 0.4 4.5 0.5 5.0 0.0

2.6 saving content in own jar 4.1 0.9 4.1 0.9 4.5 0.5

Self-Assessment: (M)

5.0 0.0 4.6 0.3 5.0 0.0

3.1 rate sensor-rec emotions 5.0 0.0 4.4 0.5 5.0 0.0

3.2 draw own emoPaint 5.0 0.0 5.0 0.0 5.0 0.0

3.3 provide self-assessment 5.0 0.0 4.3 0.5 5.0 0.0

Jar View: (M)

4.7 0.1 4.2 0.5 4.7 0.2

4.1 jar entry: preview 5.0 0.0 4.3 0.5 4.4 0.5

4.2 jar entry: review 5.0 0.0 4.5 0.5 5.0 0.0

4.3 direct access to its content 4.3 0.5 4.0 0.4 4.5 0.5

5.1 emo representation: icon 4.1 0.5 3.9 0.5 5.0 0.0

5.2 emo representation: change 4.4 0.5 4.8 0.4 5.0 0.0

6.1 random entry: with button 4.5 0.5 4.5 0.5 5.0 0.0

6.2 random entry: shake phone 2.7 0.5 3.4 0.5 3.6 0.7

Filters: (M)

4.7 0.1 4.2 0.5 4.7 0.2

7.1 a) by content type 5.0 0.0 3.6 0.5 5.0 0.0

7.1 b) by content title or author 5.0 0.0 3.5 0.5 5.0 0.0

7.1 c) by predominant emotion 5.0 0.0 4.1 0.3 5.0 0.0

7.1 d) small tooltips pop up 5.0 0.0 4.6 0.5 5.0 0.0

7.2 a) by sensor & selfassessmt 5.0 0.0 3.3 0.5 4.6 0.8

7.2 b) by date 5.0 0.0 3.5 0.5 5.0 0.0

7.2 c1) by heart rate (HR):write 5.0 0.0 4.7 0.5 4.5 0.5

7.2 c2) by HR: phone camera 5.0 0.0 4.4 0.5 3.5 0.7

7.2 c3) by HR: tapping 5.0 0.0 4.6 0.5 4.6 0.5

7.3 a) by “First” save 5.0 0.0 4.3 0.5 5.0 0.0

7.3 b) by “Repeated” saves 5.0 0.0 4.7 0.5 5.0 0.0

8

Jar Overview

5.0 0.0 4.6 0.5 4.8 0.4

Global Evaluation

4.1 0.3 4.4 0.5 4.3 0.5

Users found “convenient”, when disagreeing or

finding detected emotions incomplete. A user men-

tioned machine learning to allow precise results;

3.2) the ability to draw their own “emoPaint”

(U:5.0, S:5.0, E:5.0), which users found “original”

and an “inventive” way of providing their personal

perspective. Two users strongly appreciated the

sensor-generated “emoPaint” being automatically

replicated in their own “emoPaint” drawing area,

excusing them of trying to match the sensor-

generated one. It was not yet possible to “Undo”

potential mistakes in the drawing, only “Reset” and

draw anew. Curiously, no one complained about this

HUCAPP 2020 - 4th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

94

limitation, as they simply focused on drawing. When

alerted about it, some users said it would not be hard

to reset and replicate a drawing, but all recognized

the usefulness of having “Undo” and “Redo”.

Another limitations to be addressed in the future, is

that a user’s self-assess-ment cannot be delayed or

edited at a later time.

3.3) Overall, being able to provide self-assess-

ment about consumed content was seen as (U:5.0,

S:4.3, E:5.0). All users felt that the questions were

completely relevant (1-5 Likert scale; M: 5.0, SD:

0.0) and in the right amount (4), some stating that

more questions might become “tedious” and “labori-

ous”, and less questions would not allow to properly

explain what made the content worth saving.

4.3.4 Jar View

For Task 4 and 5, all users had in their jar the entry

that resulted from the previous tasks. From Task 6

on, they would have 13 entries to test other features.

Task 4: “Review the jar entry that was created

as a result of consuming, saving, and commenting

the selected video”. This was the users’ feedback:

To start with, just by looking at their first jar

entry it was very easy for everyone (M: 5.0, SD: 0.0)

to understand that it concerned a video, and had the

predominant emotion provided on self-assessment;

4.1) the jar entry’s preview (U:5.0, S:4.3, E:4.4),

was found “convenient” by all, as it allowed to know

about the entry’s content and self-assessment. On

the computer, all users found this preview trivial

(hovering). On the smartphone, 4 users did not know

what to do and asked for help (as stated in the

instructions it required long pressing). The other 6,

relying on previous experience with smartphones did

it well. All agreed that the entry’s preview had the

right amount of information;

4.2) the ability to review a jar entry (U:5.0,

S:4.5, E:5.0) was found instrumental in understan-

ding what made their consumed contents memorable

and ultimately worth saving. All users thought that

their entry’s information was well sorted (M: 4.5 and

SD: 0.5), but 4 mentioned that they would like to

have the sensor and user-generated “emoPaint” side

by side - challenging with the limited amount of

horizontal space on smartphones in vertical position;

4.3) the ability to directly access the content the

jar entry was about (U:4.3, S:4.0, E:4.5), considered

to be a nice shortcut to searching for that content on

the content selection page, and a quick way of

replaying content that they found memorable.

Task 5: “Change the emotion representation at

use.” and see how this reflected on their previously

created entry and both “emoPaint”. In that process,

we collected the users’ feedback on:

5.1) the multicolored icon that illustrates the

currently selected emotion representation (U: 4.1, S:

3.9, E: 5.0), which users found “handy” as it quickly

informed them of the emotion representation at use;

5.2) the ability to change to another emotion

representation (U:4.4, S:4.8, E:5.0), which all users

appreciated. After selecting one of our 3 available, 6

users stated their choice was driven by their personal

preference of colors, 2 stated they felt the selected

colors to be more representative of the emotions in

the system, and the remaining 2 said it was due to a

mix of both reasons. Most users suggested to better

highlight the current representation in the selection

dialogue, with the addition of small arrows or a text

label (which we adopted);

For the future, users would appreciate the ability

to: a) create their own emotion representation, with

their own colors (8 said, 2 were well served with the

3 options offered); and b) customize their jar (4 to

change its name, give its lid a checkered or striped

pattern, and turn its entries into emojis or make them

heart-shaped; 6 did not have much interest in this, as

they liked it in its current, unadorned form).

From Task 6 onwards, the users’ jar had 13

entries. Before these tasks, we asked users to

identify the jar’s most present emotion. All 10 users

correctly identified “Happiness”, coming to that

conclusion, they stated, through the jar’s lid, and by

checking that there were more entries with the color

of the jar’s lid than with any other color.

Task 6: “Extract a random entry from the jar”.

On both computer and smartphone, all 10 users

made quick use of the “Random” button (U:4.5, S:

4.5, E:5.0), not occurring to anyone, even those who

read the instructions, that they could shake the

smartphone. After being reminded and trying it,

most users commented that having the “Random”

button below the jar made the “shake” command

“somewhat redundant”, believing it would be faster

and easier to click on the button. Still, users found it

interesting and distinctive (U:2.7, S:3.4, E:3.6).

4.3.5 Jar Filtering

Task 7.1: “Find specific jar entries: a video called

‘Tabook’ that had made them predominantly

experience ‘Surprise’”. Then they replied about: a)

the ability and process of filtering the jar’s entries by

their content’s type (U:5.0, S:3.6, E:5.0), b) by title

or author (U:5.0, S:3.5, E:5.0), and c) by predomi-

nantly felt emotion (U:5.0,S:4.1,E:5.0); and d) the

small tooltips that pop up when a filter region is

Memorable and Emotional Media Moments: Reminding Yourself of the Good Things!

95

closed with filters active (U:5.0,S:4.6,E:5.0), a detail

that users found to be “very thoughtful” and useful.

Five users preferred the filtering process to work

the way it currently did (i.e., getting the desired

results after selecting and then applying filters), they

like to state “go-ahead” or find too distracting or

confusing to have the jar changing every time a filter

was selected or deselected (real-time); 2 would

prefer real-time, as it is what they were accustomed

to; and 3 did not have a preference;

To select “Surprise”, 7 users used the wheel of

emotions (6 because it was selected by default, and 1

because this was the favorite emotion arrangement),

and the other 3 used alphabetically ordered buttons

(because they prefer buttons and the alphabetical

order allowed quick finding of the emotion).

Task 7.2: “Find specific jar entries that

contained sensor data, were created between two

provided dates, and had the user’s current heart rate

(with tolerance of 40 bpm) as average heart rate”.

Then, we wanted the users’ feedback on:

The ability and process of filtering the jar’s

entries by a) whether or not they contain sensor

and/or self-assessment data (U:5.0, S:3.3, E:4.6), b)

the date or date interval in which these entries were

created (5-7 June, 2019) (U:5.0,S: 3.5,E: 5.0); and

c1) writing an average heart rate (U:5.0,S:4.7,E:4.5);

c2) estimating user’s average heart rate at the

time of the content’s consumption using the device’s

camera and a finger (U:5.0,S:4.4,E:3.5) was found

“unique” and “very interesting”, even if it turned out

to be “somewhat frustrating” due to its slight sensiti-

vity to changes in lighting and finger placement.

Only 4 users managed to get an estimate of their

heart rate, with 3 of them requiring more than one

try;

c3) using the tapping mechanism to estimate

one’s heart rate (U:5.0,S:4.6,E:4.6) was found “fun”

and “original”. The 4 who obtained an estimate with

the previous mechanism were pleased to see that the

tapping presented a very similar estimate. One user

mistakenly tapped the heart icon twice with each

heartbeat (contraction and relaxation), this could be

an alternative but might be more challenging to feel

and replicate, so not our (and the other 9 users)

choice.

Task 7.3: “Find the first jar entries created

about every saved content, and all jar entries about

every repeatedly saved content”.

The ability and process of a) finding the first jar

entries (U:4.6, S:4.6, E:5.0), and b) finding all

repeated entries (U:4.7, S:4.4, E:5.0) were apprecia-

ted with users considering the latter especially useful

for comparing how they felt upon subsequent con-

sumptions of the same content.

To learn about how well they understood the

views in which these first and repeated entries are

presented, we asked how many, out of a total of 13,

corresponded to a) the first time some content was

saved in the jar, b) content repeatedly saved, and c)

repeated saves of the video “Omelette”, with all

users answering correctly to the three questions.

4.3.6 Jar Overview

Finally, in Task 8: “Get an overview of one’s jar

use”, accessing the “Overview” perspective and

feeding us 9 bits of information regarding: 1) how

many times “Happiness” had been predominantly

felt, according to sensors and user’s self-assessment;

2) how many entries concerned videos, audio,

images, and text quotes; 3) how many entries have

sensor data, and how many have self-assessment

data; 4) the distribution of predominantly felt

emotions recognized by sensors and by self-

assessment in the jar; 5) the percentage of times that

the user “Agreed” with sensor’s results; 6) the

average number of words written in each self-

assessment; 7) the date of first entry ever created in

the jar; 8) the date on which the highest number of

entries were created; and 9) the overall average heart

rate of the user when consuming digital content. All

information was correctly provided, with overall

“Overview” feature rated as (U:5.0, S:4.6, E:4.8).

4.3.7 Global Evaluation

EmoJar was considered to have a quite good design

(M:4.2, SD:0.4) and found “visually appealing”. In

terms of perceived usefulness, satisfaction, and ease

of use, the overall USE ratings were (U:4.1, S:4.4,

E:4.1). As for its usability, the system’s overall SUS

score (Brooke, 1992) was very good: 89.5 out of

100.

The most appreciated details and features

included (ordered by times mentioned): the “ability

to draw one’s emotions” (7), “saving content with

emotional information associated to it” (6), “camera

and tapping mechanisms to get an estimate of one’s

heart rate” (6), “ability to change the system’s

emotion representation, and thus its colors” (5),

“Overview’ perspective” (4), “ability to filter based

on many different criteria” (3), “tooltips that inform

users of their selected filters” (3), “colored entries”

(2), “jar’s lid color changing according to the jar’s

most present emotion” (2), “ability to feel one’s

heartbeat while consuming some content” (1), and

“ability to contest the sensor’s results” (1).

HUCAPP 2020 - 4th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

96

As suggestions, users mentioned it would be

interesting to have EmoJar work in tandem with

YouTube, Spotify, Instagram, and other such

platforms. Some users commented that EmoJar had

a lot of potential, and that we should continue to

work on it, as they were unfamiliar with any other

applications that explored the emotional and well-

being dimensions of digital content consumption.

Table 2: Quality terms users chose for EmoJar.

H:Hedonic; E: Ergonomic; A: Appeal.

Terms type # Terms type #

Comprehensible

E 10

Inviting

A 8

Simple

E 10 Impressive H 7

Interesting

H 10 Familiar E 6

Aesthetic

A 10 Innovative H 6

Attractive

A 10 Good A 6

Pleasant

A 9 Exciting H 4

Clear

E 8 Motivating A 4

Original

H

8 Simpathetic A 3

In the end, users characterized EmoJar choosing

most relevant perceived hedonic, ergonomic and

appeal quality aspects (out of a total of 46: 23

positive, and 23 negative opposites) (Hassenzahl et

al., 2000). Comprehensible, Simple, Interesting,

Aesthetic, and Attractive were chosen by all the

participants, followed by Pleasant, Clear and

Inviting (Table 2).

5 CONCLUSION AND

PERSPECTIVES

Based on the Positive Psychology and Positive

Computing approaches, this paper addressed the

potential benefits of digital media content and its

consumption on individuals’ psychological well-

being; and presented and evaluated EmoJar as an

extension to Media4WellBeing, allowing users to

collect and relive emotionally impactful and memo-

rable moments.

In the user evaluation, we observed a quick and

successful completion of all tasks, and realized that

users were interested and invested in using and

exploring EmoJar. They appreciated that it allowed

them to elaborate on why certain emotions had been

felt throughout content’s consumption, and what

made said content memorable. Users also valued the

existence of EmoJar, as it allowed them to collect

content that was memorable to them, and that

positively contributed to their psychological well-

being, and to recall and reminisce upon all the

emotions, memories, thoughts, and perceptions that

resulted from consuming said content. Aligning with

exercises Seligman (2005) has shown to promote

individuals’ psychological wellbeing, revolving

around coming up with things one is grateful for.

Overall, users recognized EmoJar as useful,

satisfactory and easy to use, and capable of making

digital content consumption more meaningful and

profound. They encouraged us to develop it further,

as they found the idea behind it to be very

interesting, and the process and mechanisms by

which this system operates unlike anything they had

previously seen.

Future work includes refining based on the

evaluation, and further extending the interactive

features of EmoJar so as to provide a useful and

interesting digital experience that further supports

users in their journey of personal awareness and

development. A larger scale in terms of information

and time span is being addressed. More modalities,

like sound and haptics, are also being designed for

emotional feedback, to complement or be

experienced in alternative to the visual feedback,

e.g. to allow users to focus their visual attention to a

video they are watching, or to experience a song

with eyes closed, or yet to make the experience more

accessible to users with special perceptual needs.

The option of letting users record, comment, and

insert their own media (e.g., video or audio recor-

dings) in the jar is also a direction to explore.

EmoJar was tested in a short term usage. It is our

intention to go on enriching the user experience with

features found useful and interesting, that go in the

direction of promoting and supporting users in their

journey of self-awareness and personal develop-

ment, also in a consistent and prolonged longer term

usage.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was partially supported by FCT through

funding of the AWESOME project, ref. PTDC/CCI/

29234/2017, and LASIGE Research Unit, ref. UIDB

/00408/2020.

REFERENCES

Applied Happiness Ltd. Gratitude Garden. 2016.

https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/gratitude-garden/

id1101115763?mt=8

Bernardino, C., Ferreira, H.A., and Chambel, T. 2016.

Towards Media for Wellbeing. In Proc. of ACM TVX'

2016, ACM. 171-177.

Memorable and Emotional Media Moments: Reminding Yourself of the Good Things!

97

Brooke, J., 1996. SUS – A quick and dirty usability scale.

Usability evaluation in industry, 189(194), 4-7.

Calvo, R. A., and Peters, D., 2014. Positive computing:

Technology for wellbeing and human potential.

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chambel, T. 2011. Towards Serendipity and Insights in

Movies and Multimedia. In Proc. of International

Workshop on Encouraging Serendipity in Interactive

Systems. Interact'2011. 12-16.

Chambel, T., Oliveira, E., and Martins, P., 2011. Being

Happy, Healthy and Whole Watching Movies that

Affect our Emotions. In Proceedings of ACII 2011,

4th Int. Conf. on Affective Computing and Intelligent

Interaction, Springer. 35-45.

Chambel, T., Langlois, T., Martins, P., Gil, N., Silva, N.,

Duarte, E., 2013. Content-Based Search Overviews

and Exploratory Browsing of Movies with Movie-

Clouds. International Journal of Advanced Media and

Communication, 5(1): 58-79.

Cooper, G., 2014. HappiJar - The Happiness, Gratitude,

Blessings and Affirmations Jar & Journal. https://

itunes.apple.com/app/id692709737?mt=8&&referrer

=click=ef5237b2-fbd1-464e-ba89-0ad4ed86e02d

Dodge, R., Daly, A., Huyton, J., and Sanders, L., 2012.

The challenge of defining wellbeing. International

Journal of Wellbeing, 2(3), 222-235.

Ekman, P., 1992. Are there basic emotions? Psychological

Review, 99(3):550-553.

HappyFeed-ref: HappyFeed Inc. Happyfeed - Gratitude

Journal. https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/happyfeed-

gratitude-journal/ id707073943

Hassenzahl, M., Platz, A., Burmester, M, Lehner, K.,

2000. Hedonic and Ergonomic Quality Aspects

Determine a Software’s Appeal. In Proceedings of

ACM CHI 2000. ACM, pp.201-208.

Humane Engineering Ltd., Cove: music for mental health,

2015-19. https://apps.apple.com/app/cove-the-musi-

cal-journal/id1020256581

Janssen, J. H.,Bailenson, J. N., Ijsselsteijn, W. A., and

Westerink, J. H., 2010. Intimate Heartbeats: Oppor-

tunities for Affective Communication Technology.

IEEE Trans. on Affective Computing, 1(2), 72-80.

JarAwe-ref: Jar of Awesome app. https://play.google.com

/store/apps/details?id=com.sibayak9.jarofawesome

Kok, B. E., Coffey, K. A., Cohn, M. A., Catalino, L. I.,

Vacharkulksemsuk, T., Algoe, S. B., Brantley, M., and

Fredrickson, B. L., 2013. How Positive Emotions

Build Physical Health. Psychological Science, 24(7),

1123-1132.

Lund, A. M., 2001. Measuring usability with the USE

questionnaire. Usability and User Experience, 8(2).

Martins, S., Chambel, T., and Ferreira, H. A. 2018.

Meditative States in Personal Media Access. In

Proceedings of ICGI' 2018, International Conference

on Graphics and Interaction, Lisbon Portugal, IEEE,

pp.181-182.

Oliveira, E., Martins, P., and Chambel, T. 2013. Accessing

Movies Based on Emotional Impact. ACM/Springer

Multimedia Systems Journal, 19(6), Nov. 559-576.

Plutchik, R., 1980. Emotion: A psychoevolutionary

synthesis. Harper & Row New York.

Reinecke, L., Klatt, J., and Krämer, N. C. 2011.

Entertaining Media Use and the Satisfaction of Reco-

very Needs: Recovery Outcomes Associated with the

Use of Interactive and Noninteractive Entertaining

Media. Media Psychology, 14(2), 192-215.

Russell, J. A., 1980. A circumplex model of affect.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(6),

1161-1178.

Sacharin, V., Schlegel, K., & Scherer, K. R., 2012.

Geneva Emotion Wheel rating study (Report). Univ. of

Geneva, Swiss Center for Affective Sciences.

Seligman, M. E., Steen, T. A., Park, N., and Peterson, C.,

2005. Positive Psychology Progress: Empirical

Validation of Interventions. American Psychologist,

60(5), 410-421.

Serra, S., Jorge, A., Chambel, T., 2014. Multimodal

Access to Georeferenced Mobile Video through

Shape, Speed and Time. In Proceedings of British

HCI’2014, ACM, 347-352.

TheHappiJar-ref: The Happiness Jar app.http://www.

thehappinessjar.com/en.

HUCAPP 2020 - 4th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

98