Translating the Concept of Goal Setting into Practice: What ‘else’

Does It Require than a Goal Setting Tool?

Gábor Kismihók

1a

, Catherine Zhao

2b

, Michaéla C. Schippers

3c

, Stefan T. Mol

4d

,

Scott Harrison

5e

and Shady Shehata

6f

1

Leibniz Information Centre for Science and Technology, Hannover, Germany

2

The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia

3

Erasmus University of Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

4

University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

5

Leibniz Institute for Research and Information in Education, Frankfurt, Germany

6

YOURIKA, Waterloo, Canada

Harrison@dipf.de, sshehata@yourika.ai

Keywords: Goal Setting, Self-regulated Learning, Learning Intervention, Curriculum, MOOC, Higher Education.

Abstract: This conceptual paper reviews the current status of goal setting in the area of technology enhanced learning

and education. Besides a brief literature review, three current projects on goal setting are discussed. The paper

shows that the main barriers for goal setting applications in education are not related to the technology, the

available data or analytical methods, but rather the human factor. The most important bottlenecks are the lack

of students’ goal setting skills and abilities, and the current curriculum design, which, especially in the

observed higher education institutions, provides little support for goal setting interventions.

1 INTRODUCTION

Educational technology and ‘big’ data are having a

major impact on learning these days: disruptive forces

are modifying the modalities and strategies we choose

to learn. Subsequently, the mastery of skills and

competences enabling lifelong learning in the vast

majority of aspects and fields of education are

critically important in the 21st century (Ramsden,

2003, EUR-Lex, 2017). This movement is also

visible in the area of Self-Regulated Learning (SRL),

which has never been so actual and timely as it is

these days (Archer, 1988; Schunk and Zimmerman,

2012). As a result, the needs of individual learners,

and the integration of these needs into particular

social and technical contexts play a more and more

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3758-5455

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2791-4019

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0795-5454

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9375-3516

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6712-7784

f

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3258-6734

important role in contemporary education (Ferguson,

2012; Buckingham Shum and Ferguson, 2012).

Goal Setting (GS), as a critical and instrumental

component of SRL (Pintrich, 2000), is suggested to

be an important activity in learning intervention

designs (Wise et al, 2014). Nevertheless, GS is still

rarely used, especially in higher education despite its

demonstrated positive effects on study success (Mol

et al, 2016). Research also has shown already that

through dashboards learners can visualise and inter-

nalize learning objectives (Scheffel et al, 2014;

Verbert et al, 2014).

This paper sets out to rekindle discussions around

GS to ensure that this important aspect of SRL gets

attention and lands on the agenda of Technology

Enhanced Learning (TEL) research and practice

communities. To facilitate this conversation, we aim

388

Kismihók, G., Zhao, C., Schippers, M., Mol, S., Harrison, S. and Shehata, S.

Translating the Concept of Goal Setting into Practice: What ‘else’ Does It Require than a Goal Setting Tool?.

DOI: 10.5220/0009389703880395

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2020) - Volume 1, pages 388-395

ISBN: 978-989-758-417-6

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

to summarize lessons learned from three recent

European investigations in order to illustrate not only

the potential, but also the pitfalls of GS. We also

consider what should be the next steps for TEL

researchers and practitioners to realize the power of

GS. We hope that this paper will ignite dialogues

within the TEL community about this important SRL

concept, and that this will yield more studies and

experiments in the near future.

To achieve this, this paper starts with a brief lit-

erature review on the current state of the art of GS.

Then we discuss three GS investigations and their

outputs, followed by a discussion on the bottlenecks

and barriers facing GS research. We close our paper

with suggesting future directions for GS stakeholders.

2 GOAL SETTING IN

EDUCATION

2.1 State of the Art

The principles of GS, which were developed in the

mid-1960s by Edwin Locke, provide practical ac-

counts of motivation in both managerial and aca-

demic contexts (Locke and Latham, 2006). Locke and

his colleagues also showed that specific objectives

lead to greater performance improvement than

general ones. Furthermore, a linear relationship

between goal difficulty and task performance has

been established (Locke and Latham, 2006). Thus,

GS is economical in financial terms, and has the

potential to optimize task and academic performance

(Schippers, 2017; Schmidt, 2013).

Recent studies also confirmed the importance of

GS. Learning goals contribute to high interest, (Valle

et al, 2017) and predict improvements in academic

performance both in high school and higher education

environments (Neroni et al, 2018, Burns et al, 2018;

Schippers et al., 2020). In the area of educational

computer games, GS increases comprehension (Erhel

et al, 2019), especially when negotiation between

learners is also facilitated (besides individual GS)

(Chen et al, 2019), and affects the success of learners

on the leaderboard (Landers et al, 2017).

In a more specific frame, GS can be an integral

part of the feedback process that supports individual

learning. For students in higher education, providing

well defined feedback processes can enhance the

learning process, especially when a formal GS pro-

tocol is included in the feedback cycle (Evans, 2013,

Duffy and Azevedo, 2015). This also needs to be done

tactfully, without affecting the student's ego: “Self-

efficacy influences motivation and cognition because

it affects students’ task interest, task persistence, the

goals they set, the choices they make and their use of

cognitive, meta-cognitive and self-regulatory

strategies” (Van Dinther et al, 2010, p. 97).

This reinforces the importance of understanding

the student's state of mind and willingness to under-

take GS as a learning strategy (Lazowski and

Hulleman, 2016). “When students believed that they

could get smarter over time, they were more likely to

believe that working hard could help them succeed in

school and they endorsed the goal of learning from

coursework. These beliefs and goals motivated

greater use of effective learning strategies” (Yeager

and Walton, 2011, p. 286). Since GS can hence be

seen as an effective strategy for improving learning

trajectories, the question arises: what are the major

obstacles to the more widespread adoption of GS in

higher education?

We have seen that scepticism of psychological

intervention studies is prudent where potential bias

can be introduced, either through limited sample sizes

or where incentives artificially inflate engagement.

For example, Chase et. al (2013) constructed an

experiment testing the effects of GS under the

condition of values training. Students recruited for the

experiment (N=132) had the opportunity to “win”

goods with tangible value. Importantly, this study

found that GS alone had no effect on learning

trajectories. Only when values training was included

did students perform better, thus putting scepticism in

the centre of the issues of interventions’ scalability

and innovations, which facilitate GS.

In sum, there is evidence to show that GS can

improve students’ learning trajectories and outcomes.

However this evidence needs to be critically

challenged to best understand, what dimensions of the

GS process can be scaled, to provide support above

and beyond small scale interventions (Schippers &

Ziegler, 2019).

2.2 Three Cases of Goal Setting

Experimentations and Deployment

With the support of educational technology, design-

ing and running GS interventions – also on large

(institutional) scale – is possible. To demonstrate this,

in this paper we examine three recent attempts, which

use GS in two different educational settings (higher

education and MOOC) to investigate the relationship

between GS and learning outcomes. As it was

elaborated in these studies, researchers face a range

of problems, when it comes to motivating learners

to

set and to monitor their goals throughout their

Translating the Concept of Goal Setting into Practice: What ‘else’ Does It Require than a Goal Setting Tool?

389

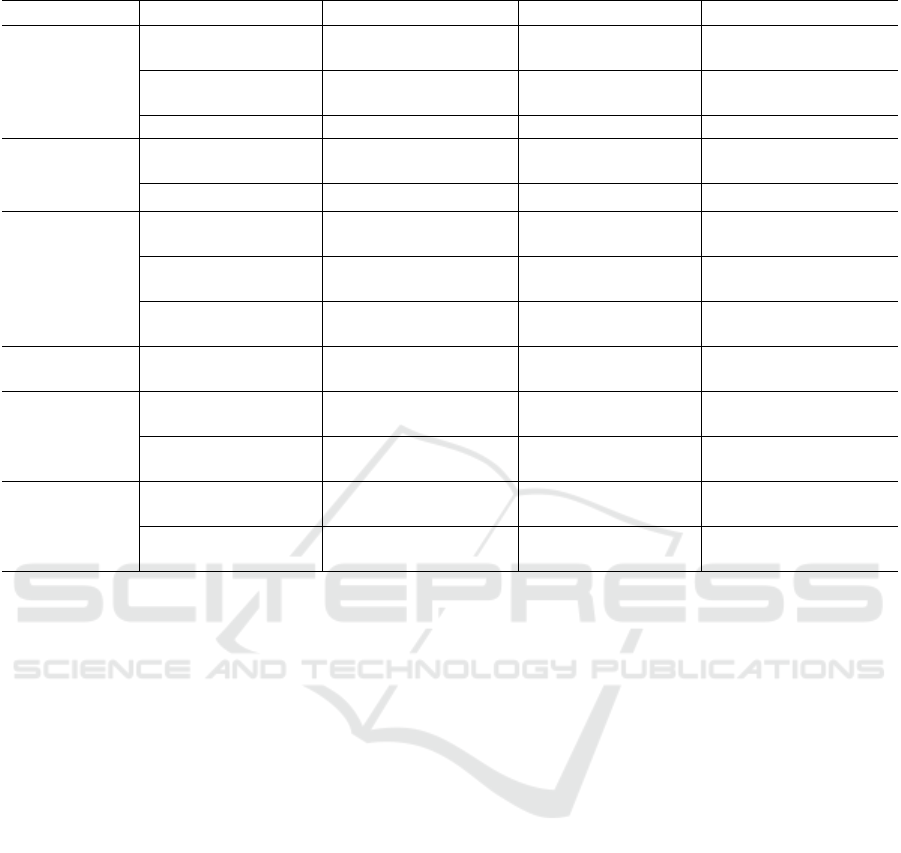

Table 1: Comparison of three goal-setting studies.

Element Dimension Schippers et. al ProSOLO Mol et. Al

Intervention

setup

Educational context

University program

based

MOOCs

University program

based

Learner participation

Opt-in informed

consent

Optional

Opt-in informed

consent

Dashboard No Yes Yes

Learners’

prior

experiences

Background of

targeted learners

University students

Corporate

professionals

University students

Assumed learner skills Metacognitive skills Not specified Not specified

Goal related

activities

Engagement time

Stage 1&2, 10 min,

photography in stage 3

Not specified Not specified

Means to set goals Write own goals

Write/Adopt external

pre-specified goals

Write/Adopt peer’s goal

Criteria for setting

goals

Practical & attainable No SMART

Feedback

Instructor feedback to

students

No No

Ratings of goals against

criteria

Support

Peer-student support No Yes

Depending on student’s

choice

Other support

Scaffolding through

‘steps’ in the system

Ad-hoc inquiry &

technical support

Ad-hoc inquiry &

technical support

Outcome

Anticipated outcome A package intervention:

“life crafting”

Foster effective self-

regulated learning

Improved academic

performance

Actual outcomes Enhanced student well-

being and performance

Learners’ uncertainty Low participation

learning journey. Therefore, we aim to shed light on

the criticality of the educational context, with a focus

on how decisions have led to different outcomes in

these studies (see table 1).

Schippers and her team (Schippers et al, 2015;

2020) designed a three staged GS intervention (with

a GS application) that scaffolds the GS process for

university first year students (n=2928) and encour-

ages them to achieve their goals. The intervention

requires students to start explicitly to conceptualize

by writing their desired future (in stage 1), and to

articulate a step-by-step plan for achieving their goals

(in stage 2). Alongside these procedures, students are

encouraged to assess practicality and attainability of

their goals, in order to stay on the ‘right’ track. At the

operational level the intervention is an integral part of

the curriculum across campus, despite the fact that it

is technically a stand-alone system. The studies by

Schippers et al. (2020) show that participation in the

intervention closed the gender and ethnicity

achievement gap (Schippers et al, 2015). Further, the

results indicate that formal participation (e.g. an

element of the assessment task) in the intervention,

the amount of writing and the quality of the writing

are the three key factors that determine the

effectiveness of GS, whilst whether or not students set

academic goals does not seem to matter. In other

words, the process by which students engage

psychologically in setting goals makes the difference

– in that it enhances the student’s self-efficacy,

optimizes effort, and psychologically better prepares

them to achieve their goals (Schippers, 2017;

Schippers et al, 2017).

The GS intervention designed by Mol and col-

leagues (Kobayashi et al, 2017) investigates the

simultaneous effect of GS on university students’

approaches to learning, and their academic perfor-

mance. The study adopts the SMART (Specific,

Measurable, Attainable, Realistic and Time-bound)

characteristics as criteria (Conzemius and O’Neill,

2009; O’Neill, 2000) that guide students in setting

effective goals. They also developed a GS tool, in

which students could compose their goals, and ap-

pend these with deadlines. This GS tool was con-

nected to a Learning Record Store (LRS) which also

set up to record additional data from the Learning

Management Systems (LMS) about students’ actual

performance during the course. The study involved

one university course at the University of Amsterdam

and courses at three Australian-based universities. In

the first lecture, students were introduced to GS

theory with an emphasis on its benefits, and the

custom developed tool and its key features. Specifi-

cally, the tool 1) allows students to set multiple main

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

390

goals and associated sub-goals, (based on the fact that

one oftentimes pursues multiple goals simultaneously

(Austin, and Vancouver, 1996)); 2) students can view

and adopt each other’s goals, but only those that are

made ‘public’ by the students who set them; 3)

students can edit or delete goals after setting them; 4)

students can view properties of goals e.g. structure,

deadlines through a dashboard, against the timeline of

their university course; 5) instructors can rate the

quality of goals against the SMART criteria, students

can view the ratings should the goal be made public.

The intervention however has attracted low student

participation in the pilot stage. The authors speculate

that reasons of, 1) GS being optional, and as such

independent of the course curriculum and not

rewarded with course credit, 2) variability in

instructors and tutors understanding of GS, 3) lack of

student support (e.g. feedback) and GS learning

resources, may have contributed to this outcome.

Furthermore, the informed consent procedure that

was employed, may have unintentionally scared some

students off, as it also requested access to their LMS

data and assessment outcomes. This latter issue also

ties into the larger question of whether GS

interventions should be positioned as a teaching tool,

a research project, or both. Framing GS in terms of a

teaching resource, may enhance face validity in the

eyes of students, although evidencing such

interventions is clearly more of a research question.

Gasevic and colleagues (Rosé et al, 2015; Jo et al,

2016; Jo et al, 2016) implemented the ProSOLO

system to encourage learners to set goals and to foster

social learning in a Massive Open Online Learning

Course (MOOC) called Data, Analytics, and

Learning. It targets corporate working professionals,

who are assumed to have a reasonably high level of

digital literacy. Compared to university campus-

based courses, MOOCs generally target educated

adult learners from much more diverse demographic

backgrounds and with a wider range of motivations.

Furthermore, there is evidence that GS predicts the

attainment of course objectives (Kizilcec et al, 2018).

Thus in the highly autonomous learning space,

ProSOLO is designed to personalize the development

of competencies, which are mapped to learning

activities throughout the MOOC. Learners are

encouraged to set up their own space that is

comprised of predefined competencies (by course

instructors) they want to develop, or their own

learning goals (if the competencies do not match), a

social network they can build by being able to follow

one another through social media, and a learning

progress feature. Learners are expected to link this

personalized hub to the assignment submission

process on the MOOC platform, toward course

completion. This approach provides opportunities for

learners who intend to purchase a certificate to

demonstrate competencies with ‘evidence’. However,

the patterns of MOOC learners’ engagement with the

system, and their discussions in the MOOC forum

point out a number of problems: 1) some learners

seem to be confused with regard to having to engage

with both the MOOC platform and ProSOLO; 2)

some learners were not familiar with the technology;

and more importantly, 3) despite high autonomy in

MOOCs, when learners are not able to make informed

choices of how to effectively learn, they fall back to

what they are familiar with, which is oftentimes, a

linear learning progression and a structured

instructional norm, rather than the social construction

of knowledge.

3 DISCUSSION

3.1 Lessons Learned from Goal Setting

Experiments

This paper unpacked the TEL related GS literature

and reviewed three technology-enhanced interven-

tions to bring forward the dimensions that are be-

lieved to be important to the success of GS interven-

tions in education. From this analysis, it emerged that

the course instructor, peer learners, and the goal-

setting interface designer play key roles in shaping

the learner’s perception of GS from the outset. In the

studies where researchers were course instructors, the

GS concept was ‘translated’ more effectively into

meaningful actions and thinking processes that were

relevant to students. However, it is worth considering

the relationship between GS and assessment. In both

Schipper’s intervention and the ProSOLO

experiment, GS is an element of assessment (despite

having a minimal or no grade attached). The possible

explanation of the difference is that assessment

matters in university learning but not in a MOOC.

Furthermore, the two interventions are very different:

The one used by Schippers and colleagues is based on

expressive writing and personal GS, (also referred to

as “life crafting”, Schippers & Ziegler, 2019), while

ProSolo is aimed at competency development. Future

research should investigate this relationship carefully.

Translating the Concept of Goal Setting into Practice: What ‘else’ Does It Require than a Goal Setting Tool?

391

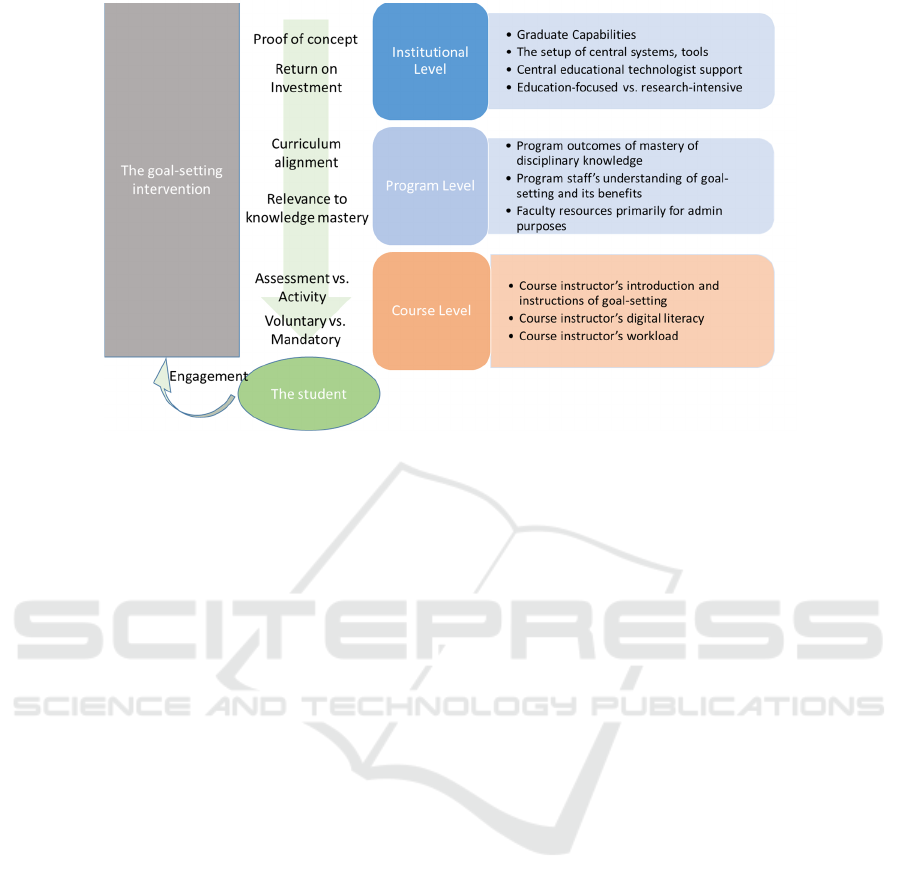

Figure 1: The multi-layer framework for an effective technology-enhanced goal-setting intervention.

Less apparent is the broader context in which

more distal stakeholders come into the play. These

include the nature of the learning episode (e.g. a

course, a program, or a MOOC), the technological

readiness of the offering university, and the institu-

tional culture. Meanwhile, the forms of education are

becoming more diverse, which attract learners with

diverse motivations to learn. Especially in MOOCs,

learning is often not tied to assessment (Jordan, 2015;

Vigentini and Zhao, 2016). While what drives

learning in MOOCs is debatable, future GS research

should respond to the challenge of how to integrate

GS into a personalized learning journey with the

support of analytics.

How to implement a technology-enhanced GS

intervention for students to make learning more

effective does not have a straight answer. While the

design and delivery process is complex, the debate

remains an educational one - how does the student

benefit from setting goals in a university course, or a

degree program? Furthermore, how may researchers

effectively demonstrate the value of GS to university

stakeholders, to initiate system development and (re-

)configuration that lays the technical foundation for

TEL to empower GS interventions?

On the other hand, the program conveyor’s per-

ception of what matters most to developing graduate

capabilities may determine the scale at which a GS

intervention is implemented (e.g. in an individual

course vs. core courses) throughout the program.

Secondly, institutional technology readiness directly

impacts on how a GS tool can be integrated into other

university supported systems. Thus university culture

to an extent shapes the way the student learns and

what the teacher teaches. To this end, researchers

should consider, where GS fits in an educational

experience that is unique to the institution. Figure 1

presents these influences at different levels on GS

interventions.

3.2 Bottlenecks for Goal Setting in

Higher Education

GS in general is “a short and seemingly simple in-

tervention (that) can have profound effects” (Wilson,

2011), and it has been supported a number of times in

the past (Morisano et al, 2010, Travers et al, 2015,

Schippers et al, 2020). However, there are several

reasons why GS implementations in higher education

can fail. Here we will focus on discussing the three

most important potential bottlenecks.

The first bottleneck is the lack of ability from the

student side to self-regulate and set goals. This has

been confirmed by a previous study (McCardle et al,

2017), and it has been especially apparent in the Mol

et al. pilot, where students failed to come up with

goals altogether. Here students’ looked at GS as an

extra assignment on top of their curricular work,

which does not help their progress, but only limits the

time to spend on reaching the course objectives.

Researchers think that this is a critical point. It is very

difficult to direct students towards setting their own

goals in relation to a course or a learning programme,

if those goals are already set by the organization or

the teacher. What happens in this case is, that students

simply copy those course objectives and spend very

little time about thinking and operationalizing their

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

392

own self developed objectives – which would be the

real benefit of GS. When this happens, goals are set

to be unrealistic and they fail to consider resources or

capabilities.

Furthermore, when students actually set goals,

oftentimes they lack the ability to evaluate crucial

information about the obstacles and challenges that

they face, in achieving their goals. Despite the evi-

dence that SRL supports cognitive and meta-cogni-

tive abilities of students (Thomas, et al, 2016), in a

learning environment, where students are pushed into

a reactive rather than a proactive role when it comes

to designing and controlling their own learning, GS

can play only a marginal role. To overcome this

problem, in the intervention used by Schippers,

students had to come up with a detailed plan to

overcome obstacles and challenges.

The second bottleneck is a more methodological

one. From the available literature and experiments it

is not obvious, what the best methods are to incorpo-

rate GS in course design (in various contexts). As it

was mentioned earlier, it is very difficult to imple-

ment effective GS mechanisms in the curricula, if

learning goals are already pre-developed and made

available for the course participants beforehand.

Methods need to be in place to co-develop these

course objectives with the students, which require

more flexible curricula. Nevertheless, the design of

GS interventions may share some similarities with

other educational approaches such as the use of e-

Portfolios (Berg et al, 2018) to develop a ‘learning

journey’.

The third methodological issue is about rewarding

students, who actually set goals. According to the

pilots, oftentimes students do not believe that the

rewards they will receive for goal accomplishment

are worth the effort that they need to invest to achieve

them. For instance, when there are too many goals to

achieve, a mechanism should be in place to prioritize

certain goals over others. In the case of the successful

Schippers’ intervention, it was shown that setting

personal goals has a rewarding effect on students.

However, the skill of setting (personal) goals

effectively is not an easy one to master, and training

this skill should not only happen in higher education,

but also much earlier in primary and secondary

education.

Thus the authors suggest further opportunities for

teaching academics to gain a more thorough under-

standing of the concept and practice of GS through

professional development programs. This skill is not

only important for students, but also for their teachers

and indeed researchers.

3.3 Integrating Goal Setting in the

Academic Program

Given that GS enhances study success, the next

question is how to make sure that as many students

profit from this intervention as possible (Schippers,

2017). However, if the GS intervention is made

optional, students may not engage with it, especially

the poor performers who may stand to benefit most.

It was learned from one of the abovementioned pilots

that when the third part of the intervention was made

optional, from 1,200 students, only 45 students

participated in that third part! Therefore, it may be

important to make the GS intervention part of the

curriculum, so both students and educational institu-

tions benefit from the positive outcomes (Schippers,

2020; Clonan et al, 2004). GS may be notably useful

when learners are in a transitional period of their

lives, as for instance progressing from school to

higher education (Schippers & Ziegler 2019; Wilson,

2011), or from higher education to the labour market

(Schippers, 2020; Berg et al, 2018). However the

effects of making GS mandatory should be further

investigated, as ownership is critical to the success of

GS.

A positive outcome from the pilots is that tech-

nical infrastructure, for collecting and analysing

learning related data in relation to goals is, in general,

not perceived as a bottleneck in GS experimentations.

4 CONCLUSIONS

GS has a number of advantages, when it comes to

applications in a number of educational contexts. The

method is easy to implement from a technical point of

view, and it works well together with existing

educational and analytical technologies. Evidence

also shows that GS can significantly improve both the

self-regulation, and the academic performance of

learners. However there are a number of barriers on

the human side, which still need substantial efforts to

overcome. The most important barriers are the low

levels of student abilities to set goals, and the current

– especially in traditional classroom settings –

methods for pre-defining learning outcomes for

learners and classes. It comes without saying that

these issues need further investigation.

The authors think that teaching and research

communities should engage in more in depth con-

versations about GS in order to understand and use

this concept better in the future. Therefore, the most

important aim of this paper was to provide ammuni-

tion for these discussions by highlighting the above

mentioned critical observations. On a positive note,

Translating the Concept of Goal Setting into Practice: What ‘else’ Does It Require than a Goal Setting Tool?

393

the authors of this paper strongly believe that, espe-

cially in the light of the ongoing GS experiments and

implementations, there is a bright future for GS in

education.

REFERENCES

Ames, C., Archer, J. 1988. Achievement goals in the

classroom: Students’ learning strategies and motivation

processes. Journal of Educational Psychology 80, 3

(1988), 260–267.

Austin, J. T., & Vancouver, J. B. 1996. Goal constructs in

psychology: Structure, process, and content.

Psychological bulletin, 120(3), 338.

Berg, A.M., Branka, J., Kismihók, G. 2018 Combining

Learning Analytics with Job Market Intelligence to

Support Learning at the Workplace. In: Digital

Workplace Learning. pp. 129–148. Springer, Cham.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-46215-8_8.

Burns, E.C., Martin, A.J., Collie, R.J. 2018. Adaptability,

personal best (PB) goals setting, and gains in students’

academic outcomes: A longitudinal examination from a

social cognitive perspective. Contemporary

Educational Psychology. 53, 57–72

Chase, J. A., Houmanfar, R., Hayes, S. C., Ward, T. A.,

Vilardaga, J. P., Follette, V., 2013. Values are not just

goals: Online ACT-based values training adds to goal

setting in improving undergraduate college student

performance, In Journal of Contextual Behavioral

Science, Vol 2, Iss 3–4, pg. 79-84

Chen, Z.-H., Lu, H.-D., Chou, C.-Y. 2019. Using game-

based negotiation mechanism to enhance students’ goal

setting and regulation. Computers & Education. 129,

71–81

Clonan, S. M., Chafouleas, S. M, McDougal, J. L., Riley-

Tillman T. C. 2004. Positive psychology goes to school:

Are we there yet? Psychology in the Schools 41, 1, 101–

110.

Conzemius A., O’Neill, J., 2009. The Power of SMART

Goals: Using Goals to Improve Student Learning.

Solution Tree Press.

Duffy, M.C., Azevedo, R. 2015. Motivation matters:

Interactions between achievement goals and agent

scaffolding for self-regulated learning within an

intelligent tutoring system. Computers in Human

Behavior. 52, 338–348.

Erhel, S., Jamet, E., 2019. Improving instructions in

educational computer games: Exploring the relations

between goal specificity, flow experience and learning

outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior. 91, 106–

114.

EUR-Lex - c11090 - EN - EUR-Lex. 2017. http://eur-

lex.europa.eu/legal-

content/EN/TXT/?uri=LEGISSUM:c11090

Evans, C., 2013 Making Sense of Assessment Feedback in

Higher Education, In Review of Educational Research,

Vol. 83, No. 1, pp. 70–120,

Ferguson, R.,2012. Learning analytics: drivers,

developments and challenges. International Journal of

Technology Enhanced Learning 4, 5–6, 304–317.

Jo, Y., Tomar, G., Ferschke, O., Rosé, C. P., Gasevic, D.

2016. Expediting support for social learning with

behavior modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:1605.02836.

Jo, Y., Tomar, G., Ferschke, O., Rosé, C. P., & Gašević, D.,

2016. Pipeline for expediting learning analytics and

student support from data in social learning. In

Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on

Learning Analytics & Knowledge, 542-543. ACM.

Jordan. K., 2015. Massive open online course completion

rates revisited: Assessment, length and attrition. The

International Review of Research in Open and

Distributed Learning 16, 3 (2015).

Kizilcec, R.F., Pérez-Sanagustín, M., Maldonado, J.J., 2017

Self-regulated learning strategies predict learner

behavior and goal attainment in Massive Open Online

Courses. Computers & Education. 104, 18–33.

Kobayashi, V., Sanagavarapu, P., Zhao, C., Mol, S.T., &

Kismihok, G., 2017. Investigating the relationships

among self-regulated learning, approach to learning,

goal orientation, LMS activity and academic

performance. In Proceedings of the 1st Learning &

Student Analytics Conference: Implementation,

Institutional Barriers and New Development,

Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Landers, R.N., Bauer, K.N., Callan, R.C., 2017

Gamification of task performance with leader-boards:

A goal setting experiment. Computers in Human

Behavior. 71, 508–515.

Lazowski, R. A., Hulleman, C. S. 2016 Motivation

Interventions in Education: A Meta-Analytic Review,

In Review of Educational Research, Vol. 86, No. 2, pp.

602– 640

Locke E. A., Latham, G. P., 2006. New directions in goal-

setting theory. Current directions in psychological

science 15, 5, 265–268.

McCardle, L., Webster, E.A., Haffey, A., Hadwin, A.F

2017. Examining students’ self-set goals for self-

regulated learning: Goal properties and patterns.

Studies in Higher Education. 42, 2153–2169.

Mol, S.T., Kobayashi, V.B., Kismihók, G. and Zhao, C.

2016. Learning through goal setting. In Proceedings of

the Sixth International Conference on Learning

Analytics & Knowledge, 512–513

Morisano, D., Hirsh, J. B., Peterson, J. B., Pihl, R. O., &

Shore, B. M. 2010. Setting, elaborating, and reflecting

on personal goals improves academic performance.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(2), 255–264.

Neroni, J., Meijs, C., Leontjevas, R., Kirschner, P.A., De

Groot, R.H.M. 2018. Goal Orientation and Academic

Performance in Adult Distance Education. irrodl. 19.

O’Neill, J., 2000. SMART Goals, SMART Schools.

Educational Leadership 57, 5 (2000), 46–50.

Pintrich, P.. 2000. The role of goal orientation in self-

regulated learning. Handbook of self-regulation 451,

(2000), 451–502

Ramsden,P., 2003. Learning to Teach in Higher Education.

Routledge

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

394

Rosé, C. P., Ferschke, O., Tomar, G., Yang, D., Howley, I.,

Aleven, V. & Baker, R. 2015. Challenges and

opportunities of dual-layer MOOCs: Reflections from

an edX deployment study. In Proceedings of the 11th

International Conference on Computer Sup-ported

Collaborative Learning (CSCL 2015) (Vol. 2).

Scheffel, M., Drachsler, H., Stoyanov, S., Specht, M. 2014.

Quality in-dicators for learning analytics. Journal of

Educational Technology & Society 17, 4, 117.

Schippers, M. C. 2017. IKIGAI: Reflection on life goals

optimizes performance and happiness (EIA-2017-070-

LIS ed.). Rotterdam: Erasmus Research Institute of

Management

Schippers, M. C., Morisano, D., Locke, E. A., Scheepers,

A. W. A., Latham, G. P., & de Jong, E. M. 2020.

Writing about personal goals and plans regardless of

goal type boosts academic performance. Contemporary

Educational Psychology, 60, 101823.

Schippers, M. C., Scheepers, A., Morisano, D., Locke, E.

A., & Peterson, J. B. 2017. Conscious goal reflection

boosts academic performance regardless of goal

domain. Manu-script submitted for publication.

Schippers, M. C., & Scheepers, A. W. & Peterson, J. B.

2015. A scalable goal-setting intervention closes both

the gender and minority achievement gap. Palgrave

Communications 1:15014

Schippers, M.C. & Ziegler, N. 2019. Life crafting as a way

to find purpose and meaning in life. Frontiers in

Psychology, 10(2778)

Schmidt. F. I. 2013. The economic value of goal setting to

employers. New develop-ments in goal setting and task

performance. 16–20.

Schunk, D. H. Zimmerman. B. J., 2012. Motivation and

Self-Regulated Learning: Theory, Research, and

Applications. Routledge.

Buckingham Shum, S., Ferguson, R. 2012. Social learning

analytics. Journal of educational technology & society

15, 3, 3.

Thomas, L., Bennett, S., Lockyer, L. 2016. Using concept

maps and goal-setting to support the development of

self-regulated learning in a problem-based learning

curriculum. Medical Teacher. 38, 930–935.

Travers, C. J., Morisano, D., & Locke, E. A. 2015. Self-

reflection, growth goals, and academic outcomes: A

qualitative study. British Journal of Educational

Psychology, 85(2), 224–241.

Valle, A., Núñez, J.C., Cabanach, R.G., Rodríguez, S.,

Rosário, P., Inglés, C.J. 2015. Motiva-tional profiles as

a combination of academic goals in higher education.

Educational Psychology. 35, 634–650.

Van Dinther, M., Dochy, F., & Segers, M., 2010, Factors

affecting students’ self-efficacy in higher education, In

Educational Research Review, Vol 6, Iss 2, Pages 95-

108

Verbert, K., Govaerts, S., Duval E.,, Santos J. l.,, Van

Assche, F., Parra, G. and Klerkx, J.. 2014. Learning

dashboards: an overview and future research

opportunities. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing 18,

6 (2014), 1499–1514.

Vigentini, L., Zhao, C., 2016. Evaluating the ’Student’

Experience in MOOCs. In Proceedings of the Third

(2016) ACM Conference on Learning@ Scale, 161–

164.

Wilson, T. 2011. Redirect: The surprising new science of

psychological change. Penguin UK.

Wise, A., Zhao, Y., Hausknech, S.T. 2014. Learning

analytics for online discussions: Embedded and

extracted approaches. Journal of Learning Analytics 1,

2, 48–71.

Yeager D. S., & Walton, G. M. 2011. Social-Psychological

Interventions in Education: They’re Not Magic. In

Review of Educational Research, Vol. 81, No. 2, pp.

267-301.

Translating the Concept of Goal Setting into Practice: What ‘else’ Does It Require than a Goal Setting Tool?

395