Face(book)ing the Truth: Initial Lessons Learned using Facebook

Advertisements for the Chatbot-delivered Elena+ Care for

COVID-19 Intervention

Joseph Ollier

1a

, Prabhakaran Santhanam

2b

and Tobias Kowatsch

2,3 c

1

Center for Digital Health Interventions, Chair of Technology Marketing,

Department of Technology, Management, and Economics, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

2

Center for Digital Health Interventions, Department of Technology, Management, and Economics,

ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

3

Center for Digital Health Interventions, Institute of Technology Management, St. Gallen, Switzerland

Keywords: Facebook Advertisements, Social Media, Digital Health, Chatbots, Elena+ Care for COVID-19.

Abstract: Utilizing social media platforms to recruit participants for digital health interventions is becoming

increasingly popular due to its ability to directly track advertising spend, number of app downloads and other

metrics transparently. The following paper concerns the initial tests completed on the Facebook Ad Manager

platform for the chatbot-delivered digital health intervention Elena+ Care for COVID-19. Eleven

advertisements were run in the UK and Ireland during August/September 2020, with resulting downloads,

post (i.e. advert) reactions, post shares and other advertisement engagement metrics tracked. Key findings

from our advertising campaigns highlight that: (i) static images with text function better than carousel of

images, (ii) Android users download and exhibit greater engagement behaviors than iOS users, and (iii)

middle-aged and older women have the highest number of downloads and the most engaged behaviors (i.e.

reacting to posts, sharing posts etc.). Lessons learned are discussed considering how other designers of digital

health interventions may benefit and learn from our results when trialing and running their own ad campaigns.

It is hoped that such discussions will be beneficial to other health practitioners seeking to scale-up their digital

health interventions widely and reach individuals in need.

1 INTRODUCTION

Social media platforms are becoming an increasingly

advantageous route to recruit participants for health

interventions (Arigo et al., 2018). They are

particularly helpful in digital interventions utilizing

smartphone technology whereby the tracking of

downloads from advertisements is easily facilitated

and costs per new participant measured (Platt et al.,

2016). The following paper overviews the

preliminary testing campaigns for the Elena+ Care for

COVID-19 (www.elena.plus) digital health

intervention, which offers chatbot-led digital

coaching on various facets of an individual’s lifestyle

and health promoting behaviors (e.g. sleep, mental

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8603-0793

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9506-4888

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5939-4145

health, physical activity etc.) that may be under

increased strain during the COVID-19 pandemic

(Ollier, Joseph & Kowatsch, 2020). It is hoped that be

demonstrating early lessons learned from early

testing campaigns, individuals running future

campaigns may be able to identify relevant patterns

earlier and save funding for more cost-effective

advertisements to help individuals in need.

The paper continues then by overviewing the

rising importance of social media in recruiting for

digital health interventions, and discussing the app

used for recruitment, Elena+ Care for COVID-19.

Following this we explain the methodological

framework and continue by exploring data exported

from the Facebook Ad Manager Platform. Lastly, we

conclude with lessons learned and future

Ollier, J., Santhanam, P. and Kowatsch, T.

Face(book)ing the Truth: Initial Lessons Learned using Facebook Advertisements for the Chatbot-delivered Elena+ Care for COVID-19 Intervention.

DOI: 10.5220/0010403707810788

In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2021) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 781-788

ISBN: 978-989-758-490-9

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

781

considerations for other designers of digital health

interventions.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Social Media Recruitment

In scaling up digital health interventions, and after the

hard work of designing, implementing and testing a

digital product, comes the next challenge of

successful recruitment (Arigo et al., 2018; Platt et al.,

2016). This challenge is often given less thought in

planning stages, however, and less focus in academic

research. A cursory search of Google Scholar with the

term “digital health intervention”, for example,

returns a huge 2 440 000 search results, however

when simply adding the additional word

“recruitment” at the end of the search term only

154 000 search results are found, and when “social

media recruitment” is added a comparably measly

136 000 search results are found. Therefore despite

the importance of successful recruitment strategies

for health interventions, social media recruitment is a

relatively neglected area in healthcare research.

Recruitment success is vital however for all

interventions, and particularly those aimed at

population level health concerns such as obesity

(Chou et al., 2014), mental health (Sanchez et al.,

2020), alcoholism (Wozney et al., 2019) or the

current paper’s example Elena+ Care for COVID-19

(Ollier, Joseph & Kowatsch, 2020). Recruitment in

such contexts is vital to generate enough participants

to both help the public at large through cutting edge

science as well as power statistical analyses which

can analyze efficacy. Additionally, for other health

interventions which target a smaller population group

and have patient access granted via a medical

organization, following up on initial success in an

academic setting with wider recruitment will likely be

a vital part of the marketing mix in translating a

promising study to a digital start up’s new digital

product (World Health Organization, 2009).

As the proportion of spending on social media

versus traditional media has been generally rising

(Ma & Du, 2018) as marketing practice has utilized

and adapted segmenting, targeting and positioning to

better effectiveness with social media platforms

(Canhoto et al., 2013; Kotler et al., 2016) for

healthcare researchers the highly utilizable nature of

social media is becoming an increasingly attractive

recruitment route. It offers more focused targeting

and opens the door for cost-effective recruitment of

participants independent of medical organizations,

which may be particularly valuable in scaling up

digital health intervention ideas into real products

actively recruiting participants (World Health

Organization, 2009).

2.2 Elena+ Care for COVID-19

The Elena+ digital health intervention is one such

example of an emerging digital product scaling up

with the use of social media advertisements for

recruitment. Elena+ (Ollier, Joseph & Kowatsch,

2020) was developed by a group of researchers during

Spring 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic spread

across the globe. It utilizes a chatbot embedded

smartphone application to address the collateral

damage of social distancing and lockdowns i.e. that

health promoting behaviors within individual’s

lifestyles may be under increased strain (Javed et al.,

2020). Therefore, the chatbot offers 43 coaching

sessions focusing on psychoeducational training and

activities in the fields of: COVID-19 information,

physical activity, sleep, anxiety, loneliness, mental

resources and diet and nutrition. The core recruitment

strategy for Elena+ was based upon Facebook

advertisements, of which findings from preliminary

experimentations are presented in this paper.

3 METHODOLOGY

During August-September 2020 advertisements were

created and displayed using the Facebook Ad

Manager platform for Facebook Businesses. A

variety of advertisements were tested which were

either (i) static images with text or (ii) a carousel of

images. Advertisements were run on both iOS and

Android smartphone operating systems and for users

within UK and Ireland in English only, with relevant

links to the app store included on the advertisements

and Facebook API for developers implemented so

that downloads resulting from the link click could be

tracked.

In total eleven advertisements were ran online, of

which; (i) eight were of static image with text type

(Figure 1) and three were carousel of images type

(Figure 2); (ii) seven were aimed at iOS users and four

at Android users; (iii) three were in the UK and eight

were in Ireland. Each advertisement was run for up to

one week, with a budget of circa 11 USD (10 CHF)

per day. Various metrics were collected by the

Facebook Ad Manager platform, and for the current

analyses we looked at downloads as the primary

result of interest, however, other engagement related

metrics for the advertisement (post engagement, page

Scale-IT-up 2021 - Workshop on Scaling-Up Healthcare with Conversational Agents

782

engagement, post reactions, post shares) were also

downloaded from the platform. Descriptive statistics

were calculated to outline the relative performance of

these advertisements.

Figure 1: Static Image with Text Advertisement.

Figure 2: Carousel of Images Advertisement.

4 RESULTS

All advertisements ran on Facebook between 13

th

August to 22

nd

September 2020, with a resulting 186

downloads at a cost of 463.24 CHF (approx. 507

USD). Although we specified a guideline budget of

10 CHF per day and to pay “cost per result” (i.e. by

downloads) some variation occurred due to increased

advertisement engagement (as Facebook states may

occur in their website documentation).

Advertisements typically ran for one week; however,

due to requirements of the Elena+ project (e.g.

maintenance tasks) outside the scope of this paper,

some fluctuations occurred. A summary can be seen

below of each advertisement, the total number of days

it ran, and total budget spent.

Table 1: Advertisement Summary.

Advert name Days Cost

Ireland Static 01

(

A

ndroid

)

7 70.40

Ireland Static 02

(

A

ndroid

)

7 76.22

UK Static 01

(

A

ndroid

)

7 59.37

UK Static 02 (

A

ndroid) 7 75.74

UK Static 01 (iO

S

) 7 60.38

Ireland Static 01

(

iO

S

)

3 3.98

Ireland Static 02

(

iO

S

)

5 38.32

Ireland Static 03

(

iO

S

)

5 35.96

Ireland Carousel 01 (iOS) 5 32.30

Ireland Carousel 02 (iOS) 3 2.10

Ireland Carousel 03 (iOS) 4 3.98

4.1 Elena+ App Downloads

Firstly, looking at simple comparisons between the

types of advertisements run, the static image with text

advertisement functioned much better than using a

carousel of images with regard to downloads.

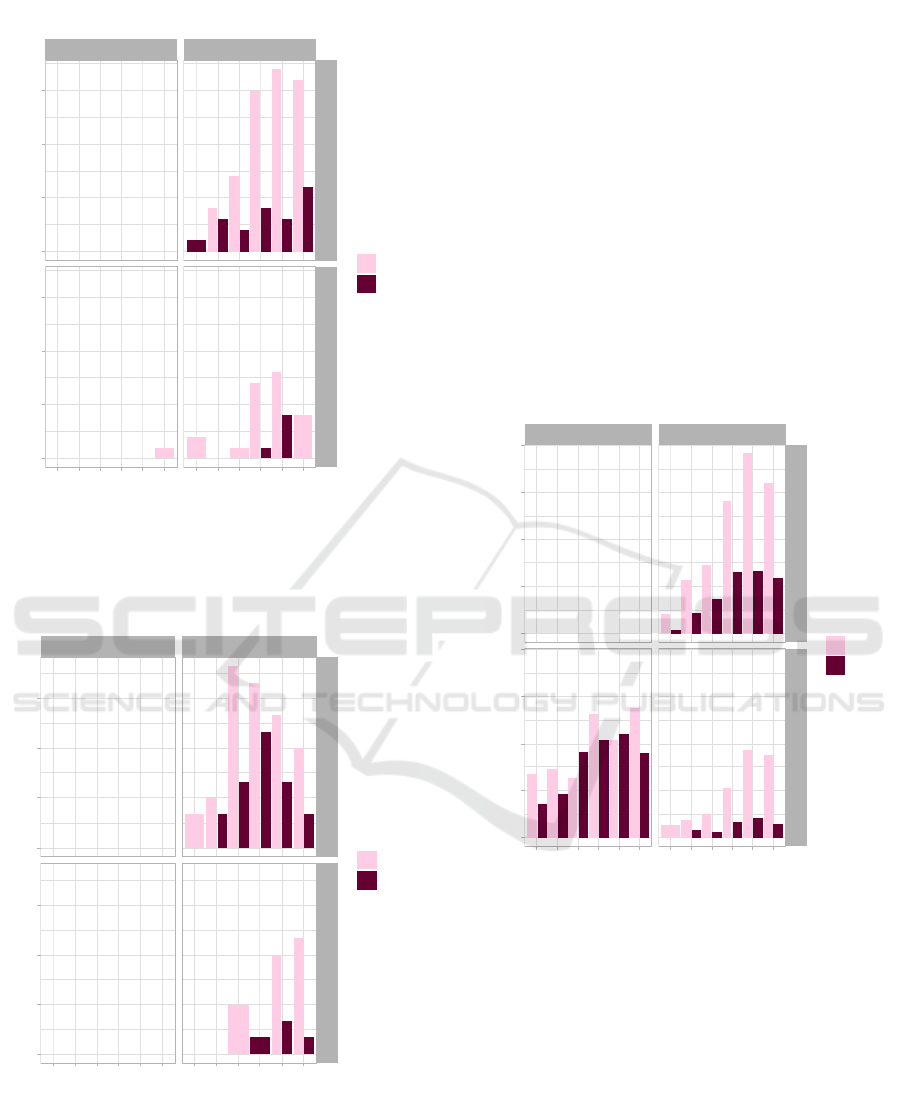

Figure 3 shows that from the three carousel

advertisements run on iOS only one download

resulted. Whereas for the eight static image with text

advertisements (which were ran on both iOS and

Android) resulted in 185 downloads. When

considering the average ad return for downloads (i.e.

no. of downloads divided by no. of advertisements

used, hereafter referred to as AAR), static image with

text resulted in 23.125 users per ad, whereas carousel

ad only 0.33 users per ad.

Face(book)ing the Truth: Initial Lessons Learned using Facebook Advertisements for the Chatbot-delivered Elena+ Care for COVID-19

Intervention

783

Figure 3: Downloads by Advertisement Type.

Figure 4: Downloads by Operating System.

When making a simple comparison between

operating system of the seven advertisements aimed

at iOS users and four advertisements at Android

users, Figure 4 shows that running advertisements on

Android resulted in much higher numbers of

downloads. From the seven advertisements aimed at

iOS users, 48 downloads resulted (AAR of 6.857)

whereas for Android it was much higher (AAR of

34.5).

Figure 5: Downloads by Country.

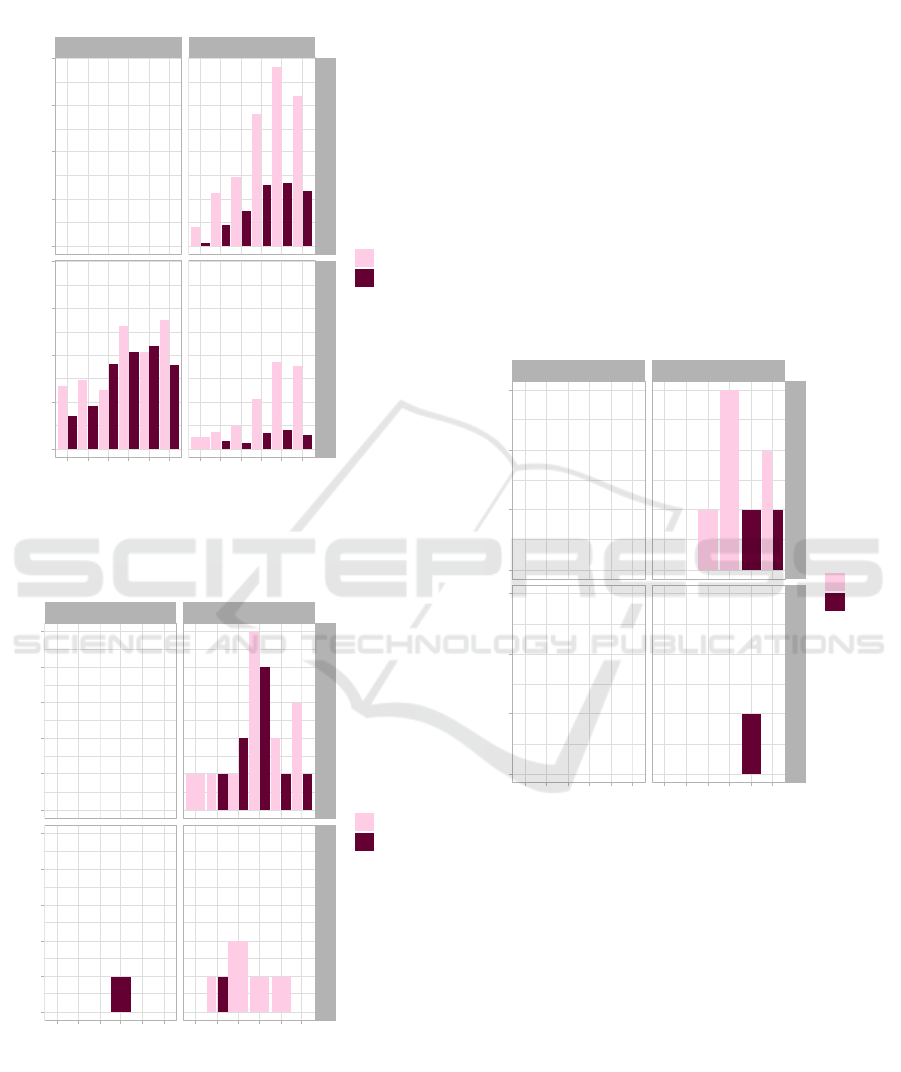

A simple comparison by country in Figure 5

shows that the eight advertisements in Ireland

resulted in 107 downloads (AAR of 13.375) whereas

the three advertisements in the U.K. resulted in 79

downloads (AAR of 26.333). Figure 6 also shows

gender and age of downloads, whereby females aged

more than 35 years are downloading the app in greater

numbers.

Figure 6: Downloads by Age and Gender.

A summary of number of downloads for all

factors discussed above is shown below for Ireland

(Figure 7) and the U.K (Figure 8).

1

185

0

50

100

150

Ca

r

ous

e

l

S

tati

c

AdType

Elena+ Downloads

Downloads by Ad Type

138

48

0

50

100

Android

iOS

Operating System

Elena+ Downloads

Downloads by OS

107

79

0

30

60

90

Ir

e

land

U

K

Country

Elena+ Downloads

Downloads by Country

4

1

7

5

22

6

32

13

39

13

34

9

0

10

20

30

40

1

8

-2

4

2

5-34

35-44

4

5

-5

4

5

5-64

65+

Age

Elena+ Downloads

Gender

fem ale

male

Downloads by Age and Gender

Scale-IT-up 2021 - Workshop on Scaling-Up Healthcare with Conversational Agents

784

Figure 7: Downloads by Ad Type, Operating System, Age

and Gender in Ireland.

Figure 8: Downloads by Ad Type, Operating System, Age

and Gender in in the U.K.

4.2 Advertisement Engagement

Metrics

To complement the above findings a brief summary

of advertisement engagement metrics is provided in

this section overviewing how the advertisements also

affected a few selected promotional metrics. These

include: (i) post engagement, (ii) page engagement,

(iii) post reactions, and (iv) post shares.

Post engagement is defined by Facebook as “all

actions people take involved your ads” such as

“reacting to, commenting on or sharing the ad,

claiming an offer, viewing a photo or video, or

clicking on a link.”. Facebook defines this as a useful

measure to see how relevant the advertisements were

to the recipients.

Figure 9: Post engagement by Age, Gender, OS and Ad

Type.

As can be seen in Figure 9, middle-aged and older

women have the highest total summed quantity of

post engagement. Static Android advertisements

drive best post engagement, as no carousel

advertisements were run on Android, comparison is

not possible however.

Page engagement includes “interactions with your

Facebook Page and its posts” and actions such as

“liking your Page, reacting with ‘Love’ to a post,

checking in to your location, clicking a link and

more.”. As with post engagement, Facebook notes

page engagement as a useful metric to see how

1

1

4

3

7

2

15

4

17

3

16

6

2

1

7

1

8

44

Carousel Static

Android iOS

18-24

25-3

4

3

5

-44

45-54

55-6

4

65

+

18-24

25-3

4

3

5

-44

45-54

55-6

4

65

+

0

5

10

15

0

5

10

15

Age

Results

Gender

fem ale

male

Downloads in Ireland

by Age, Gender, OS and Ad Type

2

3

2

11

4

10

7

8

4

6

2

3

1

6

2

7

1

Carousel Static

Android iOS

18

-

24

25-34

3

5-4

4

45

-5

4

5

5-6

4

65+

18

-2

4

2

5-3

4

3

5-4

4

4

5-54

55

-

64

65+

0

3

6

9

0

3

6

9

Age

Results

Gender

fem ale

male

Downloads in the UK

by Age, Gender, OS and Ad Type

41

21

44

28

38

55

79

6262

66

83

54

12

2

34

13

44

22

84

39

115

40

96

35

8

11

5

15

4

32

10

56

12

53

9

Carousel Static

Android iOS

18-

24

25-

34

35-44

45-54

55-64

65+

18-24

25-34

35-44

45-54

55-64

65+

0

30

60

90

120

0

30

60

90

120

Age

Post.engagement

Gender

fem ale

male

Post Engagement

by Age, Gender, OS and Ad Type

Face(book)ing the Truth: Initial Lessons Learned using Facebook Advertisements for the Chatbot-delivered Elena+ Care for COVID-19

Intervention

785

relevant the advertisements were to the given

audience.

Figure 10: Page engagement by Various Factors.

Figure 11: Post reactions by Various Factors.

The summed total on page engagement (Figure

10) is highest again for static Android advertisements,

and women from 35+ years again exhibit the highest

engagement.

Post reactions includes all types of reactions to an

ad, such as reacting with “like, love, haha, wow, sad

or angry.”. Facebook states that this helps

advertisements perform better, as individuals

automatically start to follow updates related to the ad

(i.e. new comments, reactions etc.) which can drive

further engagement with a business page and content.

As can be seen in Figure 11, post reactions are once

more best performing for static advertisements on

Android, and at least for Android users, the

aforementioned pattern of middle-aged and above

women scoring highest appears to be exhibited.

Figure 12: Post shares by Various Factors.

Post shares includes whether individuals share the

advertisement, for example on their or others’

timelines, in groups, on other pages etc. However, it

does not measure any subsequent engagement after

that point (for example, comments on shared posts, or

whether individuals that see the shared post navigate

to the original ad and take any actions). Similar to

previous results, Figure 12 indicates that general

middle-aged and older females are primarily sharing

the advertisements based on available results thus far.

41

21

44

28

38

55

79

6262

66

83

54

12

2

34

13

44

22

84

39

115

40

96

35

8

11

5

15

4

32

10

56

12

53

9

Carousel Static

Android iOS

18-

24

25

-

34

35-44

45-54

55-

64

65

+

18-24

25-34

35

-

44

45

-

54

55-64

65

+

0

30

60

90

120

0

30

60

90

120

A

g

e

Page.engagement

Gender

female

male

Page Engagement

by Age, Gender, OS and Ad Type

1

1 111

2

5

4

2

1

3

1

11

2

11

Carousel Static

Android iOS

1

8-2 4

25-34

3

5-4 4

45-

5

4

5

5-6 4

65

+

1

8-2 4

2

5

-

3

4

3

5-4 4

4

5

-

5

4

5

5-6 4

6

5+

0

1

2

3

4

5

0

1

2

3

4

5

Age

Post.reactions

Gender

fem ale

male

Post reactions

by Age, Gender, OS and Ad Type

1

3

1

2

1

1

Carousel Static

Android iOS

18-

24

25-

34

35-

44

45-

54

55-64

65+

18-

24

25-34

35-44

45-5

4

55-

64

65+

0

1

2

3

0

1

2

3

Age

Post.shares

Gender

female

male

Post shares

by Age, Gender, OS and Ad Type

Scale-IT-up 2021 - Workshop on Scaling-Up Healthcare with Conversational Agents

786

5 DISCUSSION

Our findings have highlighted that Android users are

more responsive to the advertisements in terms of

both downloads, the primary metric of interest, as

well as engagement metrics. This shows that Android

may be a more cost-effective platform as more results

were found directly from the advertisements

themselves, and via their higher engagement,

Android users effectively market the app further to

their contacts via their greater activity and

interactions with both the advertisements and the

Elena+ Facebook page. It is possible therefore that

Android users as a whole are less data privacy

sensitive, and thus interact more. This may be likely,

as Android phones can range from relatively cheap to

very expensive when bought firsthand and brand new,

whereas iOS models are always relatively expensive.

As income level is indicative of education (Tolley &

Olson, 1971), and higher digital literacy results in

more privacy protective behaviors (Park, 2011), it

may be due to less affluent/less educated individuals

being represented amongst Android users.

Regarding the prevalence of middle-aged aged

and above females being primary downloaders and

those exhibiting engaged behaviors, the authors feel

that this perhaps is related to either the ad or app

content. It may be simply that men and youth found

the simple advertisements we used less attractive, as

these groups, stereotypically, exhibit greater affinity

to new technology and technological devices (Olson

et al., 2011; Venkatesh & Morris, 2000). Thusly, for

targeting youth or men, perhaps better ad content

(media, text) was required. Alternatively, however, it

may simply represent that middle-aged and older

women are a particular at-risk group for the

intervention used in this study i.e. Elena+ Care for

COVID-19. Often middle-aged and older women are

responsible for care roles in the family (Dahlberg et

al., 2007) (i.e. caring for children, caring for elderly

relatives or both), and may also still be in

employment. Adding the additional strain of the

pandemic and social distancing/isolation

requirements on top of all other respective duties

could therefore disproportionally affect the group of

middle-aged women and could be an alternative

explanation as to why they downloaded/engaged

most often after being exposed to advertising.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In summary these preliminary findings from the

Facebook advertising campaigns are not to be taken

as definitive proof due to the relatively small budget

and duration of the campaigns and the fact that there

are likely many variations of success contingent on

the medical intervention being utilized and patient

population. However, it is hoped that by sharing our

findings on utilizing social media for driving

downloads of app, Elena+ Care for COVID-19, others

may benefit and that needless costs are not duplicated

by repeatedly running trial and error advertising

campaigns to find what works best, and may enable

practitioners to draw meaningful conclusions in their

own fields more speedily, saving budget for reaching

potential beneficiaries of their digital health

interventions.

REFERENCES

Arigo, D., Pagoto, S., Carter-Harris, L., Lillie, S. E., &

Nebeker, C. (2018). Using social media for health

research: Methodological and ethical considerations for

recruitment and intervention delivery. Digital Health,

4, 205520761877175.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2055207618771757

Canhoto, A. I., Clark, M., & Fennemore, P. (2013).

Emerging segmentation practices in the age of the

social customer. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 21(5),

413–428.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2013.801609

Chou, W. S., Prestin, A., & Kunath, S. (2014). Obesity in

social media: a mixed methods analysis. Translational

Behavioral Medicine, 4(3), 314–323.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-014-0256-1

Dahlberg, L., Demack, S., & Bambra, C. (2007). Age and

gender of informal carers: A population-based study in

the UK. Health and Social Care in the Community,

15(5), 439–445. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-

2524.2007.00702.x

Javed, B., Sarwer, A., Soto, E. B., & Mashwani, Z.-R.

(2020). Impact of SARS-CoV-2 (Coronavirus)

Pandemic on Public Mental Health. Frontiers in Public

Health, 8, 292.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00292

Kotler, P., Kartajaya, H., & Setiawan, I. (2016). Marketing

4.0: Moving from traditional to digital. John Wiley &

Sons.

Ma, J., & Du, B. (2018). Digital advertising and company

value: Implications of reallocating advertising

expenditures. Journal of Advertising Research, 58(3),

326–337. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-2018-002

Ollier, Joseph & Kowatsch, T. (2020). Elena+ Care for

COVID Website. 2020. elena.plus

Face(book)ing the Truth: Initial Lessons Learned using Facebook Advertisements for the Chatbot-delivered Elena+ Care for COVID-19

Intervention

787

Olson, K. E., O’brien, M. A., Rogers, W. A., Charness, N.,

Olson, K. E., Rogers, W. A., O’brien, M. A., &

Charness, N. (2011). Diffusion of Technology:

Frequency of use for Younger and Older Adults. Ageing

Int, 36, 123–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-010-

9077-9

Park, Y. J. (2011). Digital Literacy and Privacy Behavior

Online. Communication Research, 40(2), 215–236.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650211418338

Platt, T., Platt, J., Thiel, D. B., & Kardia, S. L. R. (2016).

Facebook Advertising Across an Engagement

Spectrum: A Case Example for Public Health

Communication. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance,

2(1), e27. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.5623

Sanchez, C., Grzenda, A., Varias, A., Widge, A. S.,

Carpenter, L. L., McDonald, W. M., Nemeroff, C. B.,

Kalin, N. H., Martin, G., Tohen, M., Filippou-Frye, M.,

Ramsey, D., Linos, E., Mangurian, C., & Rodriguez, C.

I. (2020). Social media recruitment for mental health

research: A systematic review. Comprehensive

Psychiatry, 103, 152197.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152197

Tolley, G. S., & Olson, E. (1971). The interdependence

between income and education. Journal of Political

Economy, 79(3), 460–480.

Venkatesh, V., & Morris, M. G. (2000). Why Don’t Men

Ever Stop to Ask for Directions? Gender, Social

Influence, and Their Role in Technology Acceptance

and Usage Behavior. MIS Quarterly, 24(1), 115–139.

https://doi.org/10.2307/3250981

World Health Organization. (2009). Practical guidance for

scaling up health service innovations.

Wozney, L., Turner, K., Rose-Davis, B., & McGrath, P. J.

(2019). Facebook ads to the rescue? Recruiting a hard

to reach population into an Internet-based behavioral

health intervention trial. Internet Interventions, 17,

100246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2019.100246

Scale-IT-up 2021 - Workshop on Scaling-Up Healthcare with Conversational Agents

788