Developing a Competency Framework for Intergenerational Startup

Innovation in a Digital Collaboration Setting

Irawan Nurhas

1,2 a

, Stefan Geisler

1 b

and Jan Pawlowski

1,2 c

1

Institute of Positive Computing, Hochschule Ruhr West-University of Applied Sciences, Bottrop, Germany

2

Faculty of Information Technology, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland

Keywords: Competency Framework, Intergenerational Innovation, Global Start-up, Digital Collaboration,

Computer-Supported Collaboration, Cross-generational Collaboration.

Abstract: This study proposes a framework for the collaborative development of global start-up innovators in a

multigenerational digital environment. Intergenerational collaboration has been identified as a strategy to

support entrepreneurs during their formative years. However, integrating and fostering intergenerational

collaboration remains elusive. Therefore, this study aims to identify competencies for successful global start-

ups through intergenerational knowledge transfer. We used a systematic literature review to identify a

competency set consisting of growth virtues, effectual creativity, technical domain, responsive teamwork,

values-based organization, sustainable networking, cultural awareness, and facilitating intergenerational

safety. The competency framework serves as a foundation for knowledge management research on the global

innovation readiness of people to collaborate across generations in the digital age.

1 INTRODUCTION

This research aims to highlight the competencies for

intergenerational collaboration in the digital age of

start-ups. Entrepreneurs today can expand globally

due to technological advancements. However, many

significant barriers to developing global start-ups

have been identified, including geographic isolation,

lack of trust, and aversion to imitation (Jensen, 2017;

Zakaria et al., 2004). One significant stumbling block

is a lack of competencies and successful

characteristics (Clercq et al., 2012; Giardino et al.,

2014; Nurhas et al., 2020), particularly in the early

stage when strategic organizational decisions are

often urgently needed (Clercq et al., 2012; Giardino

et al., 2014). One promising approach is an

intergenerational collaborative innovation (Matlay &

Gimmon, 2014; Underdahl et al., 2018), defined for

this study as collaboration in a virtual environment

for innovation activities between senior and younger

adults with an age difference of 20 years and more

(Brečko, 2021; Nurhas et al., 2020).

However, it remains unclear how to 1) integrate

generational competencies and 2) promote

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2211-8857

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1976-0013

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7711-1169

intergenerational collaboration for global start-up

innovation. Although society's generations change

every twenty years, managing age and

intergenerational disparities for innovation remains a

concern for companies of all sizes (Brečko, 2021).

Moreover, entrepreneurship research has identified

entrepreneurial competencies (Arafeh, 2016;

Bacigalupo et al., 2016; Dijkman et al., 2016; Kyndt

& Baert, 2015). However, little to no research

incorporates and integrates intergenerational start-up

entrepreneurship competency research into a

cohesive block of our knowledge.

Therefore, based on a systematic literature review

(Webster & Watson, 2002), we conceptualized and

discussed a required competencies for the study

context with two startup cofounders. This review

combines mature studies of required competencies

from multiple domains, such as entrepreneurship,

global innovation, intergenerational and digital

collaboration. The study proposed an eight-

competency-group framework, with each group

encompassing a different activity level related to

global innovation, intergenerational collaboration,

and digital activities.

110

Nurhas, I., Geisler, S. and Pawlowski, J.

Developing a Competency Framework for Intergenerational Startup Innovation in a Digital Collaboration Setting.

DOI: 10.5220/0010652100003064

In Proceedings of the 13th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineer ing and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2021) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 110-118

ISBN: 978-989-758-533-3; ISSN: 2184-3228

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

2 BACKGROUND

Although the terms competency and competence are

often used interchangeably to describe a skill or

required knowledge for a particular state or function

(Holtkamp et al., 2015) , we used the term

competency. The term competency typically refers to

the knowledge, skills, and abilities required to solve

specific problems in specific contexts. In this study,

we consider integrating attitudes (Bosma &

Schutjens, 2011), which include individual

preferences, virtues, and character traits (Bosma &

Schutjens, 2011; Karlson & Fergin Wennberg, 2014).

At the organizational level, organizational

capabilities combine individual and group

competencies as human resources that complement

each other to form a specific set of expertise (Saa-

Perez & Garcia-Falcon, 2002). Therefore, it is critical

to examine the individual competencies required for

start-ups to develop as an organization.

The decision to engage in intergenerational

collaboration is not an easy path for organizations;

several barriers have been identified, including

individual, perceptual, and technical/operational

(Giardino et al., 2014; Nurhas et al., 2020).

Technology is being widely used to support

intergenerational collaboration and demographically

segregated teams, becoming increasingly important

in the era of digitalization (Lyashenko & Frolova,

2014; Nurhas et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2019; Underdahl

et al., 2018).

Being an entrepreneur in a multigenerational

environment, on the other hand, requires a unique set

of skills, especially if the goal is to (transition to) an

international business model. As a result, current

research on identified competencies needs to be

expanded and complemented by global innovation.

Previous research has identified different types of

competencies for entrepreneurs, such as self-

confidence and autonomy (Arafeh, 2016; Lans et al.,

2010; Mitchelmore & Rowley, 2010), taking

calculated risks and recognizing opportunities

(Arafeh, 2016; Kyndt & Baert, 2015), creativity, and

problem-solving (Jensen, 2017; Mitchelmore &

Rowley, 2010; Rasmussen et al., 2011; Wu, 2009),

The entrepreneurs also required to take action by

transforming information into actionable strategy

(Arafeh, 2016; Bacigalupo et al., 2016; Kyndt &

Baert, 2015). Concerning global innovation, critical

elements such as creativity, cultural empathy,

teamwork, networking, and organizational space and

vision can serve as a basis for categorization (Griffith

et al., 2016; Jensen, 2017; Lombardi, 2010). This may

pave the way for the identification of complementary

competencies for this study context as needed for

intergenerational collaboration in various settings,

including family businesses (Miller et al., 2003; Shi

et al., 2019), professional and knowledge-intensive

workplace organizations, and higher education. There

is still a need to understand what competencies are

required for successful intergenerational

collaboration, especially when using digital

technologies.

3 METHOD

Systematic Literature Review (SLR) was used in this

study. SLR helps develop conceptual models based

on fragmented research (Webster & Watson, 2002)

The following research question was proposed in

response to the issues presented in the introduction:

Which competencies are required for global start-up

entrepreneurs working in intergenerational settings?

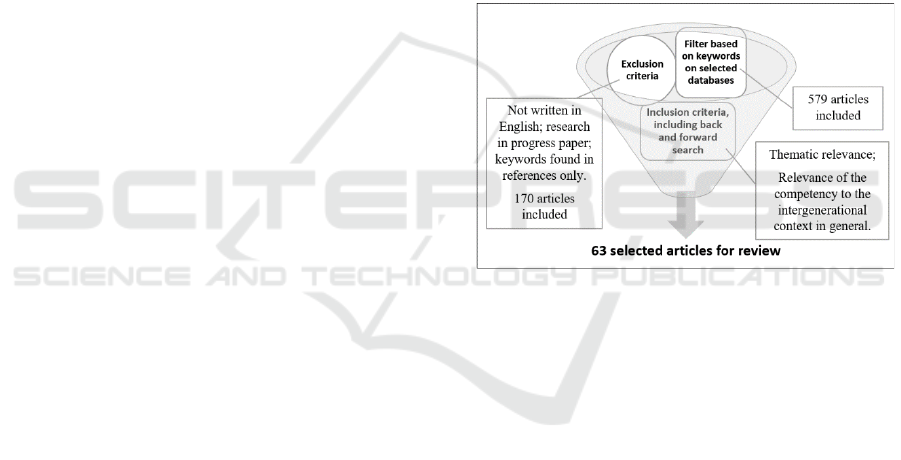

Figure 1: Systematic literature review process.

For the SLR method, the guideline of conducting

SLR (Webster & Watson, 2002) was applied. The

research phase begins with the planning process,

based on the identified research question. The

selection of keywords was defined. On October 27,

2017, the following keywords were searched for:

[[competence OR competency OR capability OR skill

OR attitude OR behavior] AND ["global innovation"

OR "Intergenerational Innovation" OR "intercultural

Innovation" OR "cross-generational Innovation"]

AND [entrepreneurs OR start-ups]]. Scholarly

databases of related disciplines such as Springerlink,

AIS e-Library, ACM Digital Library, Sciencedirect,

and information systems senior scholar “basket of

eight” journals were used to find relevant articles. For

the inclusion criteria: an article should be written in

English, highlighting the importance of studying

competencies and articles that focus on providing

relevant competencies for intergenerational learning

context, entrepreneurship, digital collaboration, and

start-ups development. For the exclusion criteria:

"Research in Progress," or short articles, an opinion

article should be removed from the list, also an article

Developing a Competency Framework for Intergenerational Startup Innovation in a Digital Collaboration Setting

111

that does not focus on competencies or impacts of

competencies.

Based on the selection process, the final 63 papers

were selected for review. Manual and iterative coding

for content analysis and conceptualization was used

to develop a more abstract level of capabilities to

cover a wide range of individual-level competencies.

Each competency mentioned or discussed in the

selected literature was noted. The identified

competencies were assigned to an initial

classification of global innovation: creativity, cultural

empathy, teamwork, networking, and organizational

space and vision (Jensen, 2017; Knight & Cavusgil,

2004) or, if not relevant, were grouped into new

categories. The label concept for the group of

competencies was refined based on the collection of

competencies. The development of the conceptual

framework was fundamentally abductive. It resulted

in an attempt to determine the best way to describe

the competencies and competency groups found in

the selected literature.

4 RESULT

Table 1 depicts the conceptual matrix (Webster &

Watson, 2002) of intergenerational start-up

competency in the digital age following the

explanation of each competency category for the

study context, which includes growth virtues (Gv),

effectual creativity (Ec), technical domain (Td),

responsive teamwork (Rt), values-driven Organizing

(Vo), sustainable networking (Sn), cultural awareness

(Ca), and intergenerational safety facilitation (Is).

While there is only one category labeled

"intergenerational," other categories are also used in

this setting.

Growth virtues are a characteristic valued by the

individual or social group; in this context, we derived

the growth virtues competency from personal

competencies. We define growth virtues as values

that belong to intergenerational start-ups' innovators

to evolve and grow to meet various global innovation

challenges. Five virtues fall into this competency

group: grit, self-determination, conscientiousness,

intergenerational reflection, and resilience. These

five competency virtues are included in the virtues of

growth because they referred to individual values

acquired through learning and shared experience and

practiced in developing digital start-ups. Growth

virtue must be present to develop and innovate further

amid global innovation and intergenerational

collaboration challenges.

Effectual creativity is associated with institutional

creativity for global innovation. Foresight thinking

and global design thinking are two competencies

included in this category. By focusing on global

innovation, both competencies are related to creating

a global business model focused on available capital,

local values, and stakeholders. Effectual creativity

creates products or services by managing future

performance based on the availability of resources.

Technical domain expertise. In this category,

several competencies are remarkably similar, namely

the operationalization of specific skills and the use of

tools. Competency in this category includes financial

negotiations, digital information fluency, legal

analysis, financial negotiations, and digital

competency associated with operating digital devices

to optimize digital information for innovation

collaboration purposes.

Responsive teamwork is a group of competencies

highlighting the importance of constructive peer

feedback for teamwork progression. The

competencies included in this category are active

listening, conflict resolution, intergenerational

orientation, auxiliary skill. These competencies share

common features supporting interpersonal

relationships in working with teams within a

generation or different generations. Furthermore,

auxiliary skill is vital to help their peers overcome

their challenges and difficulties, supporting their

organization in long-term collaboration.

Value-driven organizing. For the fourth category,

the focus of the capability covered by this dimension

is on competencies for managing and empowering the

resources based on the shared belief. The

competencies in this category include visioning,

personal resource allocation, quality orientation,

decisiveness. Visioning shows the important role of

value in providing direction for defining organization

strategy. In addition to global innovation, the ability

to manage and optimize human resources, focusing

on the quality and decisiveness by simplification

steps to make the organizational strategy more natural

to implement and minimize all forms of risk.

Sustainable networking brings together all the

skills closely linked to professional bonds outside the

organization. Three competencies for this group are

influencing, transparency, effective communication.

In the context of global innovation, global start-up

innovators require the optimization of long-term

professional networks. This provides the ability to

influence professional networks' functions and ensure

transparency and communication effectiveness of

different channels and foreign languages.

Cultural awareness is about competencies that

underline the importance of valuing cultural

differences. Under this category, a global start-up

innovator travels to another country with a different

culture, searching for partners, developing products

and services based on the global and local value in

line with its objectives. Two skills we need to

KMIS 2021 - 13th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

112

Table 1: Concept matrix.

literature

Concepts

Gv

Ec

Td

Rt

Vo

Sn

Ca

In

Abbott et al., 2013

x

x

x

x

x

x

Arafeh, 2016

x

x

x

x

Audzeyeva & Hudson, 2016

x

x

Bacigalupo et al., 2016

x

x

x

x

x

Bala et al., 2017

x

x

x

x

Barrett, 2014

x

x

Bharadwaj et al., 2010

x

x

Blackburn et al., 2003

x

x

x

x

x

x

Boughzala et al., 2012

x

x

x

Cheng & Huizingh, 2014

x

x

Czarnitzki & Lopes-Bento,

2014

x

Davis et al., 2009

x

x

x

Dijkman et al., 2016

x

x

x

x

x

Dimitratos et al., 2014

x

x

x

x

Dohmen et al., 2014

x

x

Dong & Wu, 2015

x

x

Duckworth et al., 2007

x

Duhan et al., 2001

x

x

x

x

x

x

European Communities, 2006

x

x

x

x

Fantini & Tirmizi, 2006

x

x

x

x

Foster-Fishman et al., 2001

x

x

x

Getha-Taylor, 2008

x

x

x

Goldsmith & Eggers, 2005

x

x

x

x

x

Griffith et al., 2016

x

x

Hamel, 2008

x

x

Hammer et al., 2003

x

x

Hertel et al., 2006

x

x

x

x

x

Igbaria & Baroudi, 1993

x

x

Kohli & Grover, 2008

x

x

Kollmann et al., 2009

x

x

Kungwansupaphan &

Siengthai, 2014

x

x

Kyndt & Baert, 2015

x

x

x

x

Lans et al., 2010

x

x

x

x

Li et al., 2016

x

x

x

x

x

x

Lim et al., 2013

x

x

x

Liu, 2016

x

Lombardi, 2010

x

x

Markham & Lee, 2013

x

x

x

x

Martins & Terblanche, 2003

x

x

x

x

x

Martinsons & Ma, 2009

x

x

x

Miranda & Kavan, 2005

x

Moro et al., 2014

x

x

Newman et al., 2017

x

x

Nielsen, 2015

x

x

x

x

x

Ojala, 2016

x

x

Quadros Carvalho et al., 2013

x

x

x

x

Rasmussen et al., 2011

x

x

Rasmussen et al., 2014

x

x

Reid & Brentani, 2015

x

x

Reid et al., 2014

x

x

x

Ritter & Gemünden, 2003

x

x

Sahay, 2004

x

x

x

x

Sánchez, 2013

x

x

Sarker & Sahay, 2003

x

x

x

x

x

Várhegyi & Nann, 2011

x

x

x

Vuorikari et al., 2016

x

x

Watts et al., 2013

x

x

x

x

x

x

Wei et al., 2011

x

x

Wu, 2009

x

x

x

x

x

x

Xu et al., 2007

x

x

Zakaria et al., 2004

x

x

Zimmermann & Ravishankar,

2014

x

x

x

Zimmermann et al., 2013

x

x

x

x

x

consider in this category are pluralistic thinking and

digital empathy. Digital empathy is closely linked to

cultural empathy, which is required to understand

cultural cues in virtual environments.

Intergenerational safety facilitation deals with

nurturing psychological safety in intergenerational

collaboration. Competencies include are:

intergenerational flexibility, intergenerational digital

adaptability, and intergenerational leadership.

Intergenerational flexibility can help provide a

feeling of safety to express opinions and accept

differences of opinion regarding new ideas or

approaches. In digital collaboration, each generation

can have a different background for the use of

technology. Therefore, facilitating safety for both

generations requires intergenerational digital

adaptability to facilitate workforce diversity, and no

generation feels excluded.

5 CASE STUDY

As an initial evaluation, the proposed comprehensive

list of competencies and competency groups of inter-

Generation startups-innOvators for globAL

innovation (iGOAL) can be used in the context of

human resource development to identify competency

gaps and initiate appropriate interventions (in the

form of training, matching, or recruitment processes).

For instance, a readiness indicator based on this study

result can be developed, which can be used for self-

assessment of the startup actor (s). Two case studies

were presented. We asked two different startup

founders in two different countries about required

competencies for startup development and discussed

the proposed list of competencies and the competency

group.

Developing a Competency Framework for Intergenerational Startup Innovation in a Digital Collaboration Setting

113

Case Study 1: an Indonesian IT company

founded in 2015 develops an integrated app for waste

management. The company connects community and

financial institutions for turning waste into digital

money, helping the government in decision making to

design a smart city and collaborate with consumer-

goods industries for trash management. In the context

of intergenerational collaboration, the founder (29

years old) stated, ”…very important, but right now it

is not a problem for us, because most of our team is

at the same generation age...” and currently at the

stage for expanding their business model in other

countries “…The internationalization process of the

business model right now is on the planned stage,

since now we are preparing our collaboration with

abroad partners...”

As for the assessment tool, the founder notes that

the tool could be helpful for their organization. The

founder suggests a mutual assessment with the internal

and external organization to reduce distortions in the

assessment (“…This readiness assessment tool will be

maybe helpful for our organization, but it needs an

independent assessment scoring because if we asses by

our self, there could be a bias with the score…”).

Furthermore, the founder also recommends an online

version of the tool for multiple uses, which allows the

historical assessment result of the organization to be

tracked (“I think this tool should be running on

mobile/web-based platform and can be used for

several times, so that it can track the development of

the existing score into the target score.”).

Case Study 2: a start-up was founded in 2019 by

three cross-generational co-founders (<30 years old,

mid 40, and >70 years old). The startup's focus is to

provide personal consultancy and recruit new

employees for specific vacancies, mainly in

engineering industries. For this study, the younger co-

founder described the current status of their

organization in terms of global innovation and

intergenerational collaboration. Despite the start-ups

currently focus on the local market (“…the company

is strongly oriented towards the North-Rhine-

Westphalia region (Germany). Due to the demand for

personal service, an expansion on a national or even

international level could only be implemented by a

significant increase in the number of employees..”),

the intergenerational collaboration plays an integral

part of their startup (“Due to the joint founding with

three members from different generations, it is an

integral part of the business concept. The older

generations bring experience and important business

contacts to the business, while the younger

generation is responsible for the implementation in a

digital working environment..”).

The founder took the prototype of the assessment

tool and gave some feedback, first referring to the

usefulness of the self-assessment as a starting point to

reflect the condition of current start-ups (“In

particular, the competencies and rubrics taken into

account enable a neutral assessment of one's own

status. Here, it is interesting to reflect on the relevant

contexts in order to be able to question one's own

approach critically…, the tool can certainly reveal

helpful starting points...”).

Furthermore, for improvement, the founder

proposed to add some examples for the competency

and to compare the result with peers to get a better

overview of the organization (“more detailed

explanations or examples could contribute to

understanding…”). And (“…The evaluation is

already very well presented at this point in time, but

as a participant, I can only estimate the result to a

limited extent without comparison. Here, individual

recommendations for action derived from the results

would be a huge added value for the participants…”).

The initial assessment of the proposed list of

competencies and competency groups through two

case studies demonstrates the potential of the study

result for startup founders, but also for further

investigation of the Startup Global Innovation

Readiness Assessment in the context of

intergenerational collaboration. The next section

discusses the research findings and proposes a

comprehensive overview of the study findings,

limitations, and future research directions.

6 DISCUSSION

This paper offers a comprehensive set of

intergenerational start-up innovation competencies

for the digital age. Previous research has found that

vision (Knight & Cavusgil, 2004) and personal

characteristics (soft skills) are important (Bauman &

Lucy, 2019; Karlson & Fergin Wennberg, 2014).

More importantly, we offer a comprehensive view of

innovation in an era of global digital collaboration

and workforce diversity. We supplement previous

research on global innovation success (Bauman &

Lucy, 2019; Jensen, 2017; Knight & Cavusgil, 2004)

and intergenerational competencies in start-up

development (Bauman & Lucy, 2019). (for example,

intergenerational flexibility, intergenerational

leadership, intergenerational reflection, and

orientation).

The concept of a competency group can be

defined as a group of people who complement each

other's skills. Group competency is more than just

intrapersonal or group human capital. Start-ups can

develop group competencies by matching individual

KMIS 2021 - 13th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

114

Figure 2: Intergenerational competency framework of global startup innovators in the digital age.

skills in a global and intergenerational setting. This

research enlarges eight human-based start-up capital

competencies (Jensen, 2017; Knight & Cavusgil,

2004). Between generational differences, effectual

creativity that can support unique product

development or global idea generation (Knight &

Cavusgil, 2004), value-driven organizing and cultural

awareness of other generations, quality focus, and

cultural empathy are important (Jensen, 2017). The

proposed list of group competencies highlights

growth virtues, sustainable networking, responsive

teamwork, and a group competency of

intergenerational mobility safety facilitation that

focuses on intergenerational mobility safety

facilitation.

Developing a group competency based on

individual competencies may enable founders to

concentrate on their strengths. The framework can

assist start-up stakeholders in matching and

partnering (Bauman & Lucy, 2019). Furthermore,

educational institutions can prioritize courses or

curriculum development for start-up actors based on

individual competencies. As a result, start-up actors

can cultivate critical individual competencies and

form appropriate partnerships. The findings could

also be applied to developing supportive learning

systems for global start-ups (Pawlowski et al., 2018).

In conclusion, we provide an overview of the

conceptual competency framework for the study

context shown in Figure 2, which can enable an

intergenerational ecosystem. The framework can be

used to understand and support innovation activities

based on the identified concepts from the literature

and the competency group related to the three

activities: global innovation, intergenerational

collaboration, and the use of digital technology. This

study also provides an initial qualitative assessment

of the proposed approach through open-ended

questions in two case studies. The proposed

framework could be a basis for future empirical

studies on the competency of startup founders and

promote intergenerational collaboration for startup

internationalization.

Certain limitations should be noted. First, the

literature review may not include all relevant

disciplines and literature. Therefore, this study

developed a higher/abstract competency group that

encompasses a more general level of competency. A

new relevant study that comes after the review

process, if it contains a specific competency, can be

assigned to one of the predefined categories. In

addition, the proposed conceptual framework can be

used as groundwork for future research. It can be

validated empirically with experts and start-ups

entrepreneurs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The first author received a financial grant from the

Ministry of Culture and Science of the State of North

Rhine-Westphalia to work at the Institute of Positive

Computing Hochschule Ruhr West.

REFERENCES

Abbott, P., Zheng, Y., Du, R., & Willcocks, L. (2013). From

boundary spanning to creolization: A study of chinese

software and services outsourcing vendors. The Journal

of Strategic Information Systems, 22(2), 121–136.

Developing a Competency Framework for Intergenerational Startup Innovation in a Digital Collaboration Setting

115

Arafeh, L. (2016). An entrepreneurial key competencies’

model. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship,

5(1), 26.

Audzeyeva, A., & Hudson, R. (2016). How to get the most

from a business intelligence application during the post

implementation phase? Deep structure transformation

at a UK retail bank. European Journal of Information

Systems, 25(1), 29–46.

Bacigalupo, M., Kampylis, P., Punie, Y., & van den Brande,

G. (2016). Entrecomp: The entrepreneurship

competence framework. Luxembourg: Publication

Office of the European Union, 10, 593884.

Bala, H., Massey, A. P., & Montoya, M. M. (2017). The

effects of process orientations on collaboration

technology use and outcomes in product development.

Journal of Management Information Systems, 34(2),

520–559.

Barrett, M. D. (2014). Developing intercultural competence

through education.

Bharadwaj, S. S., Saxena, K. B. C., & Halemane, M. D.

(2010). Building a successful relationship in business

process outsourcing: An exploratory study. European

Journal of Information Systems, 19(2), 168–180.

Blackburn, R., Furst, S., & Rosen, B. (2003). Building a

winning virtual team. Virtual Teams That Work:

Creating Conditions for Virtual Team Effectiveness,

95–120.

Bosma, N., & Schutjens, V. (2011). Understanding regional

variation in entrepreneurial activity and entrepreneurial

attitude in europe. The Annals of Regional Science,

47(3), 711–742.

Boughzala, I., Vreede, G.-J. de, & Limayem, M. (2012).

Team collaboration in virtual worlds: Editorial to the

special issue. Journal of the Association for

Information Systems, 13(10), 6.

Brečko, D. (2021). Intergenerational cooperation and

stereotypes in relation to age in the working

environment. Changing Societies & Personalities. 2021.

Vol. 5. Iss. 1, 5(1), 103–125.

Cheng, C. C. J., & Huizingh, E. K. (2014). When is open

innovation beneficial? The role of strategic orientation.

Journal of Product Innovation Management, 31(6),

1235–1253.

Clercq, D. de, Sapienza, H. J., Yavuz, R. I., & Zhou, L.

(2012). Learning and knowledge in early

internationalization research: Past accomplishments

and future directions. Journal of Business Venturing,

27(1), 143–165.

Czarnitzki, D., & Lopes-Bento, C. (2014). Innovation

subsidies: Does the funding source matter for

innovation intensity and performance? Empirical

evidence from Germany. Industry and Innovation,

21(5), 380–409.

Davis, A., Murphy, J. D., Owens, D., Khazanchi, D., &

Zigurs, I. (2009). Avatars, people, and virtual worlds:

Foundations for research in metaverses. Journal of the

Association for Information Systems, 10(2), 90.

Dijkman, B., Roodbol, P., Aho, J., Achtschin-Stieger, S.,

Andruszkiewicz, A., Coffey, A., Felsmann, M., Klein,

R., Mikkonen, I., & Oleksiw, K. (2016). European core

competences framework for health and social care

professionals working with older people.

Dimitratos, P., Liouka, I., & Young, S. (2014). A missing

operationalization: Entrepreneurial competencies in

multinational enterprise subsidiaries. Long Range

Planning, 47(1-2), 64–75.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2014).

The intergenerational transmission of risk and trust

attitudes. IZA Discussion Papers.

Dong, J. Q., & Wu, W. (2015). Business value of social

media technologies: Evidence from online user

innovation communities. The Journal of Strategic

Information Systems, 24(2), 113–127.

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly,

D. R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-

term goals. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 92(6), 1087.

Duhan, S., Levy, M., & Powell, P. (2001). Information

systems strategies in knowledge-based smes: The role

of core competencies. European Journal of Information

Systems, 10(1), 25–40.

European Communities. (2006). Key competences for

lifelong learning: A European reference framework.

European Union. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-

content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32006H0962&fro

m=EN

Fantini, A., & Tirmizi, A. (2006). Exploring and assessing

intercultural competence.

Foster-Fishman, P. G., Berkowitz, S. L., Lounsbury, D. W.,

Jacobson, S., & Allen, N. A. (2001). Building

collaborative capacity in community coalitions: A

review and integrative framework. American Journal of

Community Psychology, 29(2), 241–261.

Getha-Taylor, H. (2008). Identifying collaborative

competencies. Review of Public Personnel

Administration, 28(2), 103–119.

Giardino, C., Wang, X., & Abrahamsson, P. (2014). Why

early-stage software startups fail: A behavioral

framework. In International conference of software

business (pp. 27–41). Springer.

Goldsmith, S., & Eggers, W. D. (2005). Governing by

network: The new shape of the public sector. Brookings

institution press.

Griffith, R. L., Wolfeld, L., Armon, B. K., Rios, J., & Liu,

O. L. (2016). Assessing intercultural competence in

higher education: Existing research and future

directions. ETS Research Report Series, 2016(2), 1–44.

Hamel, G. (2008). The future of management. Human

Resource Management International Digest.

Hammer, M. R., Bennett, M. J., & Wiseman, R. (2003).

Measuring intercultural sensitivity: The intercultural

development inventory. International Journal of

Intercultural Relations, 27(4), 421–443.

Hertel, G., Konradt, U., & Voss, K. (2006). Competencies

for virtual teamwork: Developmentand validation of a

web-based selection tool for members of distributed

teams. European Journal of Work and Organizational

Psychology, 15(4), 477–504.

Holtkamp, P., Jokinen, J. P. P., & Pawlowski, J. M. (2015).

Soft competency requirements in requirements

KMIS 2021 - 13th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

116

engineering, software design, implementation, and

testing. Journal of Systems and Software, 101, 136–146.

Igbaria, M., & Baroudi, J. J. (1993). A short-form measure of

career orientations: A psychometric evaluation. Journal

of Management Information Systems, 10(2), 131–154.

Jensen, K. R. (2017). Leading Global Innovation:

Facilitating Multicultural Collaboration and

International Market Success. Springer.

Karlson, N., & Fergin Wennberg, E. (2014). Virtue as

Competence in the Entrepreneurial Society. The Ratio

Institute.

Knight, G. A., & Cavusgil, S. T. (2004). Innovation,

organizational capabilities, and the born-global firm.

Journal of International Business Studies, 35(2), 124–

141.

Kohli, R., & Grover, V. (2008). Business value of it: An

essay on expanding research directions to keep up with

the times. Journal of the Association for Information

Systems, 9(1), 1.

Kollmann, T., HäSel, M., & Breugst, N. (2009).

Competence of it professionals in e-business venture

teams: The effect of experience and expertise on

preference structure. Journal of Management

Information Systems, 25(4), 51–80.

Kungwansupaphan, C., & Siengthai, S. (2014). Exploring

entrepreneurs’ human capital components and effects

on learning orientation in early internationalizing firms.

International Entrepreneurship and Management

Journal, 10(3), 561–587.

Kyndt, E., & Baert, H. (2015). Entrepreneurial competencies:

Assessment and predictive value for entrepreneurship.

Journal of Vocational Behavior, 90, 13–25.

Lans, T., Biemans, H., Mulder, M., & Verstegen, J. (2010).

Self ‐ awareness of mastery and improvability of

entrepreneurial competence in small businesses in the

agrifood sector. Human Resource Development

Quarterly, 21(2), 147–168.

Li, W., Liu, K., Belitski, M., Ghobadian, A., & O'Regan, N.

(2016). E-leadership through strategic alignment: An

empirical study of small-and medium-sized enterprises

in the digital age. Journal of Information Technology,

31(2), 185–206.

Lim, J.-H., Stratopoulos, T. C., & Wirjanto, T. S. (2013).

Sustainability of a firm's reputation for information

technology capability: The role of senior it executives.

Journal of Management Information Systems, 30(1),

57–96.

Liu, F. H. (2016). Interactions, innovation, and services.

The Service Industries Journal, 36(13-14), 658–674.

Lombardi, M. R. (2010). Assessing intercultural competence:

A review. NCSSSMST Journal, 16(1), 15–17.

Lyashenko, M. S., & Frolova, N. H. (2014). Lms projects:

A platform for intergenerational e-learning

collaboration. Education and Information Technologies,

19(3), 495–513.

Markham, S. K., & Lee, H. (2013). P roduct d evelopment

and m anagement a ssociation's 2012 c omparative p

erformance a ssessment s tudy. Journal of Product

Innovation Management, 30(3), 408–429.

Martins, E.-C., & Terblanche, F. (2003). Building

organisational culture that stimulates creativity and

innovation. European Journal of Innovation

Management.

Martinsons, M. G., & Ma, D. (2009). Sub-cultural

differences in information ethics across china: Focus on

chinese management generation gaps. Journal of the

Association for Information Systems, 10(11), 2.

Matlay, H., & Gimmon, E. (2014). Mentoring as a practical

training in higher education of entrepreneurship.

Education+ Training.

Miller, D., Steier, L., & Le Breton-Miller, I. (2003). Lost in

time: Intergenerational succession, change, and failure

in family business. Journal of Business Venturing,

18(4), 513–531.

Miranda, S. M., & Kavan, C. B. (2005). Moments of

governance in is outsourcing: Conceptualizing effects

of contracts on value capture and creation. Journal of

Information Technology, 20(3), 152–169.

Mitchelmore, S., & Rowley, J. (2010). Entrepreneurial

competencies: A literature review and development

agenda. International Journal of Entrepreneurial

Behavior & Research.

Moro, A., Fink, M., & Kautonen, T. (2014). How do banks

assess entrepreneurial competence? The role of

voluntary information disclosure. International Small

Business Journal, 32(5), 525–544.

Newman, L., Browne‐Yung, K., Raghavendra, P., Wood,

D., & Grace, E. (2017). Applying a critical approach to

investigate barriers to digital inclusion and online social

networking among young people with disabilities.

Information Systems Journal, 27(5), 559–588.

Nielsen, J. A. (2015). Assessment of innovation

competency: A thematic analysis of upper secondary

school teachers’ talk. The Journal of Educational

Research, 108(4), 318–330.

Nurhas, I., Geisler, S., Ojala, A., & Pawlowski, J. M. (2020).

Towards a wellbeing-driven system design for

intergenerational collaborative innovation: A literature

review. In Hawaii international conference on system

sciences. University of Hawai'i at Manoa.

Ojala, A. (2016). Business models and opportunity

creation: How it entrepreneurs create and develop

business models under uncertainty. Information

Systems Journal, 26(5), 451–476.

Quadros Carvalho, R. de, dos Santos, G. V., & de Barros

Neto, Manoel Clementino (2013). R&D+ I strategic

management in a public company in the brazilian

electric sector. Journal of Technology Management &

Innovation, 8(2).

Rasmussen, E., Mosey, S., & Wright, M. (2011). The

evolution of entrepreneurial competencies: A

longitudinal study of university spin ‐ off venture

emergence. Journal of Management Studies, 48(6),

1314–1345.

Rasmussen, E., Mosey, S., & Wright, M. (2014). The

influence of university departments on the evolution of

entrepreneurial competencies in spin-off ventures.

Research Policy, 43(1), 92–106.

Developing a Competency Framework for Intergenerational Startup Innovation in a Digital Collaboration Setting

117

Reid, S. E., & Brentani, U. de (2015). Building a

measurement model for market visioning competence

and its proposed antecedents: Organizational

encouragement of divergent thinking, divergent

thinking attitudes, and ideational behavior. Journal of

Product Innovation Management, 32(2), 243–262.

Reid, S. E., Brentani, U. de, & Kleinschmidt, E. J. (2014).

Divergent thinking and market visioning competence:

An early front-end radical innovation success typology.

Industrial Marketing Management, 43(8), 1351–1361.

Ritter, T., & Gemünden, H. G. (2003). Network competence:

Its impact on innovation success and its antecedents.

Journal of Business Research, 56(9), 745–755.

Saa-Perez, P. D., & Garcia-Falcon, J. M. (2002). A

resource-based view of human resource management

and organizational capabilities development.

International Journal of Human Resource Management,

13(1), 123–140.

Sahay, S. (2004). Beyond utopian and nostalgic views of

information technology and education: Implications for

research and practice. Journal of the Association for

Information Systems, 5(7), 1.

Sánchez, J. C. (2013). The impact of an entrepreneurship

education program on entrepreneurial competencies

and intention. Journal of Small Business Management,

51(3), 447–465.

Sarker, S., & Sahay, S. (2003). Understanding virtual team

development: An interpretive study. Journal of the

Association for Information Systems, 4(1), 1.

Shi, H. X., Graves, C., & Barbera, F. (2019).

Intergenerational succession and internationalisation

strategy of family smes: Evidence from china. Long

Range Planning, 52(4), 101838.

Underdahl, L., Isele, E., Leach, R. G., Knight, M., & Heuss,

R. (2018). Catalyzing cross-generational

entrepreneurship to foster economic growth, employ

youth, and optimize retiree experience. In Icie 2018 6th

international conference on innovation and

entrepreneurship: Icie 2018 (p. 434). Academic

Conferences and publishing limited.

Várhegyi, V., & Nann, S. (2011). Framework model for

intercultural competences. On Behalf of Luminica Ltd.

For the Intercultool Project. European Commission.

Vuorikari, R., Punie, Y., Gomez, S. C., & van den Brande,

G. (2016). DigComp 2.0: The digital competence

framework for citizens. Update phase 1: The

conceptual reference model. Joint Research Centre

(Seville site).

Watts, F., Le Aznar-Mas, Penttilä, T., Kairisto-Mertanen,

L., Stange, C., & Helker, H. (Eds.) (2013). Innovation

competency development and assessment in higher

education.

Webster, J., & Watson, R. T. (2002). Analyzing the past to

prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. MIS

Quarterly, xiii–xxiii.

Wei, K.-K., Teo, H.-H., Chan, H. C., & Tan, B. C. Y. (2011).

Conceptualizing and testing a social cognitive model of

the digital divide. Information Systems Research, 22(1),

170–187.

Wu, W. W. (2009). A competency-based model for the

success of an entrepreneurial start-up. WSEAS

Transactions on Business and Economics, 6(6), 279–291.

Xu, Q., Chen, J., Xie, Z., Liu, J., Zheng, G., & Wang, Y.

(2007). Total innovation management: A novel

paradigm of innovation management in the 21st century.

The Journal of Technology Transfer, 32(1-2), 9–25.

Zakaria, N., Amelinckx, A., & Wilemon, D. (2004).

Working together apart? Building a knowledge ‐

sharing culture for global virtual teams. Creativity and

Innovation Management, 13(1), 15–29.

Zimmermann, A., Raab, K., & Zanotelli, L. (2013). Vicious

and virtuous circles of offshoring attitudes and

relational behaviours. A configurational study of

german it developers. Information Systems Journal,

23(1), 65–88.

Zimmermann, A., & Ravishankar, M. N. (2014). Knowledge

transfer in it offshoring relationships: The roles of social

capital, efficacy and outcome expectations. Information

Systems Journal, 24(2), 167–202.

KMIS 2021 - 13th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

118