Assessing Business Performance of the Traditional Market Trader:

The Role of Buyer-supplier Relationship and Dynamic Capabilities

Moh Farid Najib

a

Business Administration Department, Bandung State Polytechnic, Indonesia

Keywords: Buyer-Supplier Relationship, Dynamic Capabilities, Business Performance.

Abstract: Traditional market competition is not only facing the development of modern markets, and competition

among traders. Therefore, the importance of buyer-supplier relations and the dynamic capabilities of traders

is driving their business performance. The purpose of this study is to empirically examine the impact of the

buyer-supplier relationship on business performance, and the mediating effect of dynamic capabilities. This

study is based on empirical data collected from a survey of 840 traditional market traders in West Java,

Indonesia on 69 traditional markets. Structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to test the research

question by using the two stages. The first measuring the model by confirming the loading factor, Cronbach’s

alpha, variance extracted, construct reliability and discriminant validity. Secondly, testing the structural

model. This study provides evidence that the business performance of traditional market traders is

significantly linked to the buyer-supplier relationship and dynamic capabilities. The buyer-buyer relationship

can build the dynamic capabilities of traditional market traders, which in turn can improve their business

performance. This research contributes to the literature by providing empirical evidence that buyer-supplier

relationship and dynamic capabilities of traditional market traders need to be continuously improved to ensure

the availability of products and the competitiveness.

1 INTRODUCTION

The buyer-supplier relationship is an essential

phenomenon in the context of industrial business

marketing management because it can provide the

partners with the opportunities to access important

resources for the incorporation and creation of value

(Lunnan & Haugland, 2008). In supply chain

management the role of the buyer-supplier

relationship is very important

(Bello et al., 2003; Dyer

& Chu, 2003; Najib et al., 2017). Buyer-supplier

relationships in this context refer to the "Business to

Business" construct. Thus, the important role of the

relationship of buyer-supplier is; to control the

diversity and utilization of knowledge, mobilizing

resources, and coordinating, in other words,

marketing and logistical perspectives, which means

that the relationship of buyer-supplier has been

identified as having a significant influence on buyer

satisfaction and being a significant measure to

anticipate the sustainability of the business

relationships (Daugherty et al., 1998). The buyer-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2064-6779

supplier relationship provides competitiveness for

companies (Prior, 2012), provides improvements in

the marketing process (Asare et al., 2013), and is a

key element of supplier relationships, including,

long-term relationships (Rajagopal & Rajagopal,

2009), can improve business performance (Ambrose

et al., 2010; Hsu et al., 2008; Najib et al., 2017).

Purchasing efficiency and optimization of operating

costs are a form of successful management of buyer-

supplier relationships and the overall supply portfolio

(da Silveira & Arkader, 2007; Ketchen Jr & Hult,

2007).

Therefore, to build the achievement of a good

form of relationship, dynamic capabilities must be

supported. Therefore, the importance of research on

dynamic capabilities because the business

performance of a company can be improved through

dynamic capabilities. The dynamic capability has a

significant positive effect on business performance,

although there is no strong empirical evidence in the

research literature that supports this idea (Helfat et al.,

2009; M. Hitt et al., 2001). The concept of dynamic

Najib, M.

Assessing Business Performance of the Traditional Market Trader: The Role of Buyer-supplier Relationship and Dynamic Capabilities.

DOI: 10.5220/0010743200003112

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences (ICE-HUMS 2021), pages 73-81

ISBN: 978-989-758-604-0

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

73

capabilities essentially has implications for the

capabilities of the company in utilizing resources

within the company but is also related to the renewal

and development of its capabilities (Najib et al.,

2017). The principle of dynamic capability is to

reconstruct and improve the core capabilities in

response to the dynamic market to improve the

performance and sustainability of competitive

advantage

(Dadashinasab & Sofian, 2014). An

understanding of the competitive value of market

orientation needs to be illustrated from the

perspective of dynamic capabilities (Eisenhardt &

Martin, 2000; Teece, 2007; C. L. Wang & Ahmed,

2007). The dynamic capabilities concept has

improved the view of resource-based by anticipating

the changing of company resources and ability

concerning the changing of environmental and allows

to identify the important specific processes for the

company or industry evolution

(Hou, 2008). A

strategy of streamlining responsibility can improve

business performance through developing and

improving a company's dynamic capability (Hervas-

Oliver et al., 2013).

This research focuses on traditional market traders

in Indonesia who are seen as small businesses in the

retail sector. The traditional market facing many

challenges in the midst of changing the map of retail

business competition in Indonesia. It’s because the

quality of modern market services shows better than

traditional markets (Najib & Sosianika, 2018). This

research aims to contribute in the field of respective

research in explaining, what is the relationship

between buyer-supplier relationships, dynamic

capabilities of business performance among

traditional market traders.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Buyer-supplier Relationship

The key elements of the buyer-supplier relationship,

such as; long-term relationships, communication,

cross-functional teams, and supplier integration

which are followed at different levels of the

transaction process (Rajagopal & Rajagopal, 2009).

The indicators of supplier relevance consist of four,

namely; trust, commitment, information sharing, and

idiosyncratic partner of investment (Prior, 2012). The

buyer-supplier relationships are built through, such

as; hones communication, task competence, quality

assurance, interactional courtesy, legal compliance,

and, financial balance (Gullett et al., 2009). The

buyer-supplier relationships are built through; trust,

commitment, communication, resource dependence,

adaptation, and uncertainty (Ambrose et al., 2010).

The conclusion (Najib et al., 2017) states that buyer-

supplier relationships are built through; contract of

agreement, cooperation norms, information

exchange, operational linkage, and adaptation by

seller and buyer.

2.2 Dynamic Capabilities

Dynamic capabilities as abilities that help parts in

expanding, modifying, and reconfiguring operational

capabilities while leading to new capabilities that are

more suitable for changing environments

(Pavlou &

El Sawy, 2011). Dynamic capability is defined as the

company's capability to integrate, build and

reconfigure internal and external competencies to

deal quickly with environmental changes (Zheng et

al., 2011). The core of dynamic capabilities is the

capability of organizations to develop, renew and

maintain various resources (including tangible,

intangible, and human resources) to create customer

value (Mauludin et al., 2013).

The dynamic capabilities can be achieved

through; sensing, learning, integration, and

coordination capability (Gathungu & Mwangi, 2012).

The dynamic capabilities over three dimensions,

namely; integration capability, power capability,

innovation capability (Tiantian, Gao; Yezhuang,

Tian; Qianqian, 2014). The dynamic capabilities

consist of; sensing, absorptive, integration, and

innovation capability (Hou, 2008; Najib et al., 2017).

2.3 Business Performance

Business performance is a fundamental of responsive

market orientation (RMO) and proactive market

orientation (PMO) (Voola & O’Cass, 2010). The end

result of an activity is performance (Thomas &

Hunger, 2012). The business performance is

fundamentally driven by the level of competition in

the market where the company chooses to operate,

which in turn is a function of the structural

characteristics of that part of the market (Morgan,

2012). Because, company performance generally

refers to organizational success, and success is

considered as achieving organizational goals. Thus,

company performance is important and the

determinants index to determine the efficiency and

effectiveness of the company (Najmabadi et al.,

2013).

Measuring business performance can be done by

waiting for market performance and financial

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

74

performance (Hsu et al., 2008). The measurement of

business performance can be done by measuring

customer retention, sales growth, operating profit

margin, return on investment, and return on equity,

(Najmabadi et al., 2013), market share growth, sales

growth, and profitability (Najib et al., 2017). The

measured business performance through

measurements of average net profit growth, the value

of work received, the number of contracts received,

and the number of contracts renewed (Hussin et al.,

2014). The company's performance is something

important and a determining index to determine the

efficiency and effectiveness of the company

(Najmabadi et al., 2013).

2.4 Buyer-supplier Relationship,

Dynamic Capabilities, and Business

Performance

The buyer-supplier relationship has been identified a

significant effect on buyer satisfaction and it's a

measure of significance in anticipation of the

sustainability of business relationships (Daugherty et

al., 1998), and made a positive contribution to

business performance (Helfat et al., 2009; M. A. Hitt

et al., 2001). The buyer-supplier relationships are also

able to provide competitiveness for companies (Prior,

2012), provide improvements in the marketing

process (Asare et al., 2013), and as the key

components of supplier relationships, including long-

term relationships (Rajagopal & Rajagopal, 2009),

improving a business performance (Ambrose et al.,

2010; Hsu et al., 2008; Najib et al., 2017). The

management of the buyer-supplier relationship will

provide results which include; overall supply

portfolio, improved supply efficiency and optimal

operating costs

(da Silveira & Arkader, 2007;

Ketchen Jr & Hult, 2007).

The buyer-supplier relationship has a very

important role in supply chain management

(Bello et

al., 2003; Doney & Cannon, 1997; Dyer & Chu, 2003;

Sako & Helper, 1998). It can produce strategic

benefits, especially a deep relationship with the

interdependence of the company as a buyer or

supplier (Chanchai et al., 2015), then it can be utilized

to improve business performance (Barringer &

Harrison, 2000).

Therefore, capability in managing relationships is

an important one (Kale et al., 2002; Schreiner et al.,

2009; Y. Wang & Rajagopalan, 2015). The role of a

company's dynamic capabilities as an important

source of competitive advantage is also very

important. This dynamic capability has resulted in a

research focus on processes within the company. The

purpose of the research on dynamic capabilities is to

develop and renew its’ resource base to deal with

dynamic environmental changes (Hou, 2008; Pavlou

& El Sawy, 2011; Teece, 2007; Zheng et al., 2011).

Thus, the research hypothesis can be constructed as

follows;

H

1

: Buyer-supplier relationship is positively related

to business performance

H

2

: Dynamic capability is positively related to

business performance

H

3

: Buyer-supplier relationship is positively related

to dynamic capabilities

3 METHOD

3.1 Survey Instrument

The survey instrument was developed using a five-

point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, neutral,

disagree, and strongly disagree). The operational

variables of each construct are the result of the

elaboration of theories, as follows: the supplier

relationship variable with 16 items is developed from

the results of the construct elaboration used by some

research such as (Ambrose et al., 2010; Gullett et al.,

2009; Najib et al., 2017; Prior, 2012; Rajagopal &

Rajagopal, 2009). Furthermore, the variable of

dynamic capabilities with 11 items was developed

from the results of the construct elaboration used by

(Gathungu & Mwangi, 2012; Hou, 2008; Najib et al.,

2017; Tiantian et al., 2014). And for business

performance variables with 13 items was developed

from the results of the construct elaboration used by

(Hsu et al., 2008; Hussin et al., 2014; Najib et al.,

2017).

3.2 Data Collection

The data used to test the proposed hypotheses were

collected from the results of a survey of 840 traders

in 69 traditional markets in West Java, Indonesia,

with 477 (56.6%) male respondents and 363 (43.2%)

male gender profiles, from the business experience

that 286 (34%) had more than 15 years, 191 (22.7%)

had between 10 years and 15 years, 185 (22%) had

between 5 years and 10 years, and 178 (21.2%) have

been less than 5 years. The education level of

respondents showed 141 (16.8%) had an elementary

school, 239 (28.5%) had a junior high school, 388

(46.2%) had a high school, 44 (5.2%) had graduated

diploma, and 28 (3, 3%) Bachelor's degree.

Assessing Business Performance of the Traditional Market Trader: The Role of Buyer-supplier Relationship and Dynamic Capabilities

75

Furthermore, the status of the kiosks used for selling

shows as many as 450 (53.5%) of their own and 390

(46.4%) of rent. Out of 840 respondents, 657 (78.2%)

had business licenses and 183 (21.8%) did not have

business licenses.

Structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to

test the research question by using the two stages. The

first measuring the model by confirming the loading

factor, Cronbach’s alpha, variance extracted,

construct reliability and discriminant validity.

Secondly, testing the structural model.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Result

4.1.1 Measurement Model

Measurements used to test the hypotheses of this

research are carried out using Structural Equation

Modelling (SEM). Therefore, two processing phases

are used, the first is the measurement model using the

first order-Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and

followed by the SEM. The general practice for both

types of tests is to base the decision on

accepting/rejecting various test statistics (e.g. AGFI,

GFI, SRMR, NFI, CFI, RMSEA) (Hair et al, 2009),

all of which have flaws. It becomes very dependent

on the strength of the test (Saris & Gallhofer, 2014).

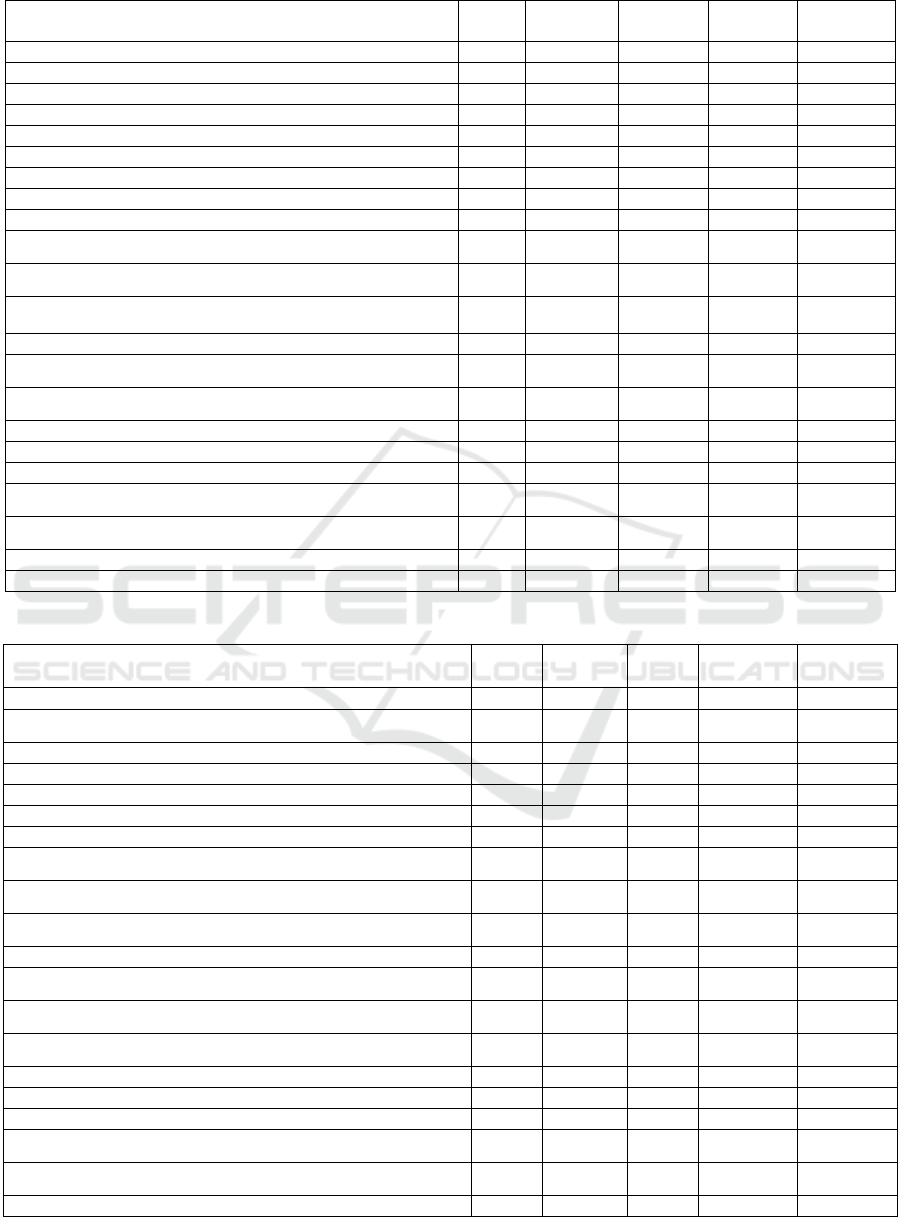

The results of validity and reliability are determined

by measuring the level of loading factor, variance

extracted (VE), construct reliability (CR),

discriminant validity (DC) and Cronbach's alpha (see

Table 1, Table 2, and Table 3).

Measurement results of the model as shown in

table 1, table 2 and table 3 using Confirmatory factor

analysis (CFA) of exogenous construction (buyer-

supplier relationship) can be accepted (CMIN =

2.498). The measurement model of absolute

compatibility index is accepted (RMSEA = 0.059),

additional indexes and GFI = 0.932, AGFI = 0.921,

TLI = 0.950, NFI = 0.942, CFI = 0.963, IFI = 0963,

RFI = 0.936, (Hair, et al, 2009). And, the endogenous

construct confirmation factors analysis (dynamic

capability) can also be accepted (CMIN = 2.783), and

the absolute compatibility index of the measurement

model that is acceptable (RMSEA = 0.076) with

additional indexes and GFI = 0.905, AGFI = 0.901,

TLI = 0.946, NFI = 0.934, CFI = 0.943, IFI = 0.943,

RFI = 0.990 The last confirmatory factor analysis for

other endogenous constructs (business performance)

is acceptable (CMIN = 2.630), and the absolute match

index of the measurement model that can be accepted

with (RMSEA = 0.064) with additional indices and

GFI = 0.921, AGFI = 0.906, TLI = 0.948, NFI =

0.924, CFI = 0.959, IFI = 0.959, RFI = 0.921.

The results of measuring the goodness of fit index

criteria have shown the results are greater or equal to

the suitability measure Therefore, a confirmatory

analysis for all latent variables used in this study can

be concluded that the theoretical concepts for

indicators and manifest (Figure 2). However, these

results are not sufficient to measure the suitability of

the model, this means that an evaluation of the

construct validity is still needed. Because the

construct validity can provide confidence that the size

of the indicators / sub indicators taken from the

sample represents the population. Measuring the

validity of the construction can be done through CV,

AVE, CR, and, DC.

The results of construct validity as shown in table

1, table 2 and table 3 show that CV, AVE, CR, and,

DC. The convergent validity is measured by the value

of the loading factor. Convergent validity is an

indicator that constructs must converge or share a

high proportion of variance. The results from the

estimated standard loading estimates as shown in

table 2 that all loading factors are above 0.5. The

estimated standardized loading must be equal to 0.50

or more and ideally 0.70. The loading factor must be

equal to 0.30 for a sample size of at least 350

respondents (Hair, 2009). This means that for 840

respondents all loading factors are acceptable.

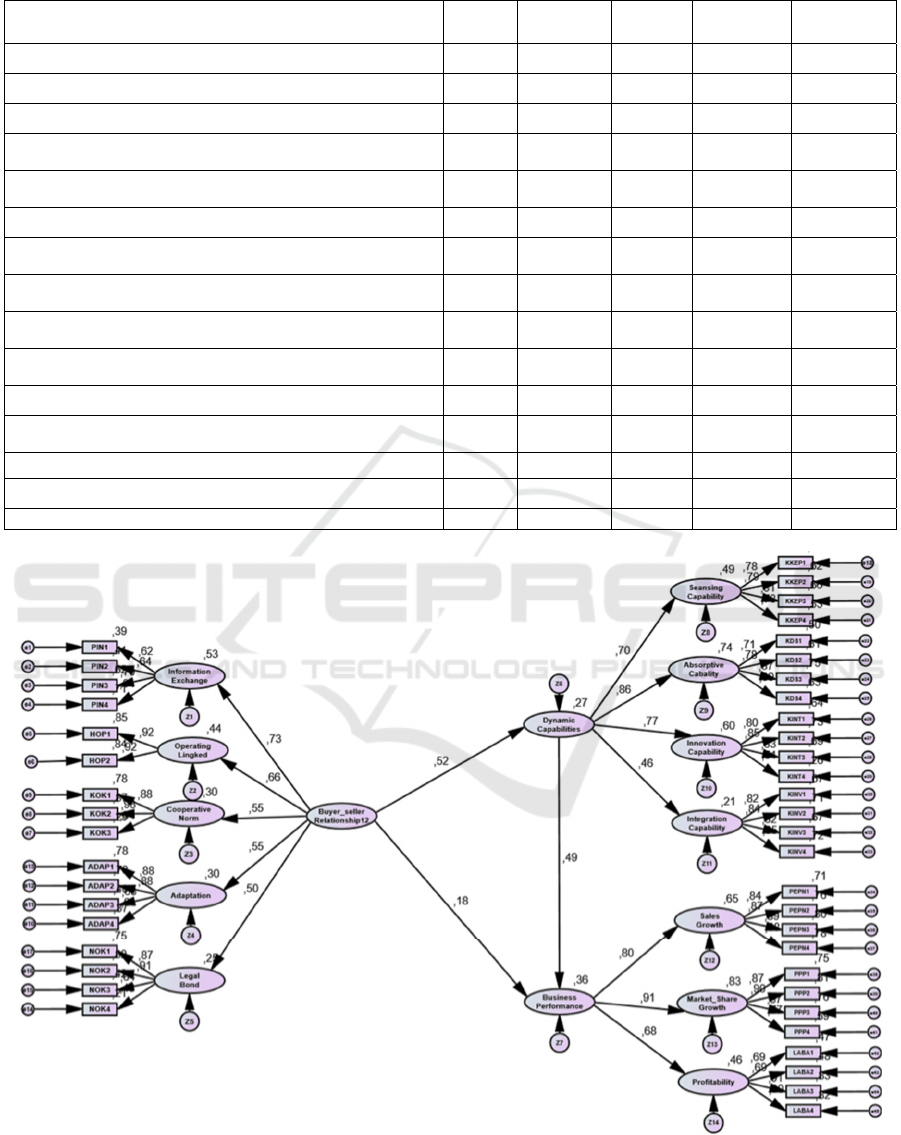

4.1.2 Structural Equation Modelling

The first measurement results show the level of

acceptable goodness of fit and validation of the

construct, then the next step is the measurement of the

structural model. Figure 1 shows the overall model of

the structural equation. The study purpose is to

empirically examine the influence between the buyer-

supplier relationship and business performance, and

dynamic capabilities as a mediating variable. Figure

1, shows the influence of the buyer-supplier

relationship, dynamic capabilities, and business

performance. For more details, table 4 shows the

testing of the research hypothesis.

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

76

Table 1: Validity and reliability construct variable buyer-supplier relationship.

Descriptions

Loading

Facto

r

Cronbach’s

alpha

Variance

Extracte

d

Construct

Reliabilit

y

Discriminant

Validit

y

Information Exchange

0.823 0.528 0.881 0.727

Quality of information received from suppliers 0.844

Quality of information provided to suppliers 0.796

Frequency of receiving information from your suppliers 0.626

Frequency of providing information to your suppliers 0.612

Operating Linkage

0.916 0.846 0.955 0.920

Implement

p

rocedures for supply/purchase 0.911

Implement a system of supply/purchase activities 0.928

Cooperative Norm

0.842 0.664 0.909 0.815

The level of congruence between expectations and reality

in

p

rofitable coo

p

eration with su

pp

liers

0.634

The level of compatibility between expectations and reality

after transactin

g

with su

pp

liers

0.918

The level of conformity between expectations and reality

when dealin

g

with su

pp

liers

0.864

Adaptation

0.853 0.580 0.900 0.761

Ability to adjust/adapt errors in the number of products

made b

y

the su

pp

lie

r

0.605

Ability to adjust/adapt to product type errors made by the

su

pp

lie

r

0.629

Ability to adjust/adapt supply procedures by supplie

r

s 0.882

Ability to adjust/adapt the supply system by the supplie

r

0.883

Legal Bon

d

0.851 0.573 0.892 0.757

The level of speed in finding transaction documents with

su

pp

lie

r

s

0.893

The level of neatness in documenting each transaction with

the su

pp

lie

r

0.923

The level of commitment to the agreement with the supplie

r

0.582

The level of agreement that is built with the supplie

r

0.550

Table 2: Validity and reliability construct variable dynamic capabilities.

Descriptions

Loading

Facto

r

Cronbach’s

alpha

Variance

Extracte

d

Construct

Reliabilit

y

Discriminant

Validit

y

Sensing Capability

0.858 0.605 0.916 0.778

The capability to understand the dynamics that develop in the

market

0.733

The capability to understand customer needs 0.811

Capability to feel the dynamics that develop in the market 0.785

Capability to satisfy customer needs 0.780

Absorptive Capabilit

y

0.856 0.623 0.916 0,790

Capability applies new values/information to the business 0.798

Capability assimilates/adjusts the value/new information in the

b

usiness

0.872

Capability to recognize new information developments in the

b

usiness environment

0.775

Capability to recognize new values that develop in the

b

usiness environment

0.704

Innovation Capabilit

y

0.899 0.691 0.942 0.831

The capability to develop new markets (expansion) with

innovative

p

rocesses

0.845

The capability to develop new markets in harmony with

innovative behavio

r

0.823

The capability to develop new types of products with

innovative

p

rocesses

0.842

The level of capability to develop innovative new products 0.815

Integration Capabilit

y

0.827 0.578 0.898 0.760

Capability to implement integrated inputs 0.508

Capability ability to make an integrated input/suggestion

effective

0.826

Capability to apply patterns of integration of interactions in

b

usiness

0.854

Capability to be effective when integrating with the business 0.801

Assessing Business Performance of the Traditional Market Trader: The Role of Buyer-supplier Relationship and Dynamic Capabilities

77

Table 3: Validity and reliability construct variable business performance.

Descriptions

Loading

Facto

r

Cronbach’s

alpha

Variance

Extracte

d

Construct

Reliabilit

y

Discriminant

Validit

y

Sales Growth

0.928 0.762 0.960 0.873

The increase in the types of products sold 0.885

The increase in the number of products sold 0.893

The increase in the type of product requested by the

custome

r

0.869

The increase in the number of products requested by the

custome

r

0.845

Market Share Growth

0.912 0.728 0.960 0.853

The growth of the market share that is the business market

forces

0.766

The growth of the market shares due to the capability of

b

usiness efficienc

y

0.868

The growth of the market share of the number of products

sol

d

0.903

The growth of the number of the market share of the types

of

p

roducts sol

d

0.870

Profitability

0.880 0.649 0.927 0.806

The level of ability to maintain business management

efficienc

y

0.906

The level of ability to manage the business efficiently 0.910

Level of ability to generate the profits 0.691

The increasing income from business 0.686

Figure 1: Structural equation model of buyer-supplier relationship, dynamic capability and business performance.

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

78

Table 4: Hypothesis Testing Result.

Hypotheses

Standardized

(Estimated)

SE CR p-value Result

H

1

Buyer-Supplier Relationshi

p

Dynamic Capability .940 .147 6.414 .001 Accepted

H

2

Dynamic Capability

Business Performance .593 .083 7.185 .001 Accepted

H

3

Buyer-Supplier Relationshi

p

Business Performance .384 .119 3.236 .001 Accepted

4.2 Discussion

SEM results, as shown in Table 4, state that H

1

(perceptions of traditional market traders in the

buyer-supplier relationship are directly and positively

related to dynamic capabilities) and show that the

CR/Critical Value is 6.414, and the significance of the

P-value (probability) is significant. In other words,

the regression weights for the predicted dynamic

capabilities in the buyer-supplier relationship differ

significantly from zero at the 0.05 level (two sides),

so it is decided to reject Ho and accept Ha. Therefore,

building a buyer-supplier relationship can improve

the capabilities of the company to increase the

competitiveness of the company (Asare et al., 2013;

Prior, 2012), building a buyer-supplier relationship

can increase purchasing efficiency and optimizing of

the operational costs (da Silveira & Arkader, 2007;

Ketchen Jr & Hult, 2007). Buyer-supplier

relationships are built through; information exchange,

operating linkage, cooperative norm, adaptation

between seller and buyer, and legal bond. The highest

quality of buyer and supplier relationships can

increase the dynamic capabilities of traditional

market traders because the various information

obtained from suppliers can be anticipated in the face

of changing the business environment. Therefore, to

build the achievement of a good form of the

relationship of the dynamic capabilities must be

supported.

H2 (traditional market traders' perceptions of

dynamic capabilities are directly and positively effect

to business performance). The results showed that the

CR is 7,185 for the effect of dynamic capabilities on

business performance, and the significance of the

p<0.001 which meant by default was significant. The

regression weight for the business performance of

traditional market traders is predicted by significant

dynamic capabilities; it was decided to accept Ho and

reject Ha.

H3 (traditional market traders' perception of the

buyer-supplier relationship is directly and positively

effect to business performance). The results showed

that the CR is 3.326 for the influence of the

relationship of buyers and suppliers on the business

performance, and the significance of the p<0.001

means by default is significant. The regression weight

for business performance is predicted by the

relationship between buyer and buyer significantly; it

was decided to accept Ho and reject Ha.

Hypotheses 2 and 3. Buyer-supplier relations and

dynamic capabilities have been proven to affect

business performance, both in sales growth, market

share growth, and profitability. The results of this

study proved to support several previous studies, such

as; (Helfat et al., 2009; M. Hitt et al., 2001) that the

principle of dynamic capability is to reconstruct and

enhance the core capabilities in response to the

dynamic market to improve the performance and

sustainability of competitive advantage

(Dadashinasab & Sofian, 2014). While buyer-

supplier harmony has been identified as having a

significant influence on business performance

(Ambrose et al., 2010; Daugherty et al., 1998; Hsu et

al., 2008; Najib et al., 2017; Prior, 2012; Rajagopal &

Rajagopal, 2009)..

5 CONCLUSIONS

The research finding indicates the importance of the

buyer-supplier relationship for traditional market

traders because it can increase the availability of

products so that customers will become satisfied and

can improve the business performance of traditional

market traders through; sales growth, market share

growth, and profitability. However, the buyer-

supplier relationship needs to be supported by

dynamic capabilities owned by traders. The buyer-

supplier harmony can, on the one hand, improve

business performance. It can increase dynamic

capabilities of traditional market traders.

However, this study has several limitations such

as the sample size, which is only represented in the

area of West Java province, even though this province

has the largest population in Indonesia. On the other

hand, this research focuses on traditional market

traders only, so to see a general picture of competition

in the retail industry needs to compare with modern

markets (supermarkets, hypermarkets, and mini

Assessing Business Performance of the Traditional Market Trader: The Role of Buyer-supplier Relationship and Dynamic Capabilities

79

markets). Because this research has not analyzed the

comparison with modern markets, the problem can be

continued in subsequent studies. Although this study

has proven to support the hypothesis related to buyer-

supplier relationships, dynamic capabilities, and

business performance, a longitudinal study can be

offered to provide further, more interesting insights.

REFERENCES

Ambrose, E., Marshall, D., & Lynch, D. (2010). Buyer

supplier perspectives on supply chain relationships.

International Journal of Operations & Production

Management. 30(12), 1269-1290.

doi:10.1108/01443571011094262

Asare, A. K., Brashear, T. G., Yang, J., & Kang, J. (2013).

The relationship between supplier development and

firm performance: the mediating role of marketing

process improvement. The Journal of Business and

Industrial Marketing, 28(6), 523–532.

Barringer, B. R., & Harrison, J. S. (2000). Walking a

tightrope: Creating value through interorganizational

relationships. Journal of Management, 26(3), 367–403.

Bello, D. C., Chelariu, C., & Zhang, L. (2003). The

antecedents and performance consequences of

relationalism in export distribution channels. Journal of

Business Research, 56(1), 1–16.

Chanchai, T., D., M. M., D, T. R., & J., M. A. (2015). A

review of buyer-supplier relationship typologies:

progress, problems, and future directions. Journal of

Business & Industrial Marketing, 30(2), 153–170.

doi:10.1108/JBIM-10-2012-0193.

da Silveira, G. J. C., & Arkader, R. (2007). The direct and

mediated relationships between supply chain

coordination investments and delivery performance.

International Journal of Operations & Production

Management, 27(2), 140-158. doi:10.1108/01443

570710720595

Dadashinasab, M., & Sofian, S. (2014). The impact of

intellectual capital on firm financial performance by

moderating of dynamic capability. Asian Social

Science, 10(17), 93.

Daugherty, P. J., Stank, T. P., & Ellinger, A. E. (1998).

Leveraging logistics/distribution capabilities: the effect

of logistics service on market share. Journal of Business

Logistics, 19(2), 35.

Doney, P. M., & Cannon, J. P. (1997). An examination of

the nature of trust in buyer–seller relationships. Journal

of Marketing, 61(2), 35–51.

Dyer, J. H., & Chu, W. (2003). The role of trustworthiness

in reducing transaction costs and improving

performance: Empirical evidence from the United

States, Japan, and Korea. Organization Science, 14(1),

57–68.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic

capabilities: what are they? Strategic Management

Journal, 21(10‐11), 1105–1121.

Gathungu, J. M., & Mwangi, J. K. (2012). Dynamic

capabilities, talent development and firm performance.

DBA Africa Management Review, 2(3), 83-100

Gullett, J., Do, L., Canuto-Carranco, M., Brister, M.,

Turner, S., & Caldwell, C. (2009). The buyer–supplier

relationship: An integrative model of ethics and trust.

Journal of Business Ethics, 90(3), 329–341.

Hair, J. F, et al. (2009) Multivariate Data Analysis: A

Global Perspective. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River:

Prentice Hall.

Helfat, C. E., Finkelstein, S., Mitchell, W., Peteraf, M.,

Singh, H., Teece, D., & Winter, S. G. (2009). Dynamic

capabilities: Understanding strategic change in

organizations. John Wiley & Sons.

Hervas-Oliver, J.-L., Tsai, P. C.-F., & Shih, C.-T. (2013).

Responsible downsizing strategy as a panacea to firm

performance: the role of dynamic capabilities.

International Journal of Manpower. 34(8), 1015-1028.

doi:10.1108/IJM-07-2013-0170

Hitt, M. A., Ireland, R. D., Camp, S. M., & Sexton, D. L.

(2001). Guest editor’s introduction to the special issue

strategic entrepreneurship. Strategic Management

Journal, 22(6/7), 479–492.

Hitt, M., Ireland, D., Camp, M., & Sexton, D. (2001). Guest

editors’ introduction to the special issue: Strategic.

Strategic Management Journal, 22(6), 7.

Hou, J.-J. (2008). Toward a research model of market

orientation and dynamic capabilities. Social Behavior

and Personality: An International Journal, 36(9),

1251–1268.

Hsu, C., Kannan, V. R., Tan, K., & Leong, G. K. (2008).

Information sharing, buyer‐supplier relationships, and

firm performance. International Journal of Physical

Distribution & Logistics Management. 38(4), 296-310.

doi:10.1108/09600030810875391

Hussin, M. H. F., Thaheer, A. S. M., Badrillah, M. I. M.,

Harun, M. H. M., & Nasir, S. (2014). The Aptness of

Market Orientation Practices on Contractors’ Business

Performance: A Look at the Northern State of Malaysia.

International Journal of Social Science and Humanity,

4(6), 468–473. doi:10.7763/ijssh.2014.v4.400

Kale, P., Dyer, J. H., & Singh, H. (2002). Alliance

capability, stock market response, and long‐term

alliance success: the role of the alliance function.

Strategic Management Journal, 23(8), 747–767.

Ketchen Jr, D. J., & Hult, G. T. M. (2007). Bridging

organization theory and supply chain management: The

case of best value supply chains. Journal of Operations

Management, 25(2), 573–580.

Lunnan, R., & Haugland, S. A. (2008). Predicting and

measuring alliance performance: A multidimensional

analysis. Strategic Management Journal, 29(5), 545–

556.

Mauludin, H., Alhabsji, T., Idrus, S., & Arifin, Z. (2013).

Market orientation, learning organization and dynamic

capability as antecedents of value creation. Learning

Organization and Dynamic Capability as Antecedents

of Value Creation, Journal of Business and

Management, 10(2), 38-48

Morgan, N. A. (2012). Marketing and business

performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

80

Science, 40(1), 102–119.

Najib, M. F., Kartini, D., Suryana, Y., & Sari, D. (2017).

Market orientation, buyer-supplier relationship and

firm performance with dynamic capabilitis as an

intervening variable: a research model. International

Journal of Business and Globalisation, 19(4), 567–582.

doi: 10.1504/IJBG.2017.087300

Najib, M. F., & Sosianika, A. (2018). Retail service quality

scale in the context of Indonesian traditional market.

International Journal of Business and Globalisation,

21(1), 19–31. doi:10.1504/IJBG.2018.094093

Najmabadi, A., Rezazadeh, A., & Shoghi, B. (2013).

Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: the

moderating effect of organizational structure. Asian

Journal of Research in Business Economics and

Management, 3(2), 142-164.

Pavlou, P. A., & El Sawy, O. A. (2011). Understanding the

elusive black box of dynamic capabilities. Decision

Sciences, 42(1), 239–273.

Prior, D. D. (2012). The effects of buyer‐supplier

relationships on buyer competitiveness. Journal of

Business & Industrial Marketing. 27(2), 100-114.

doi:10.1108/08858621211196976

Rajagopal, & Rajagopal, A. (2009). Buyer–supplier

relationship and operational dynamics. Journal of the

Operational Research Society, 60(3), 313–320.

Sako, M., & Helper, S. (1998). Determinants of trust in

supplier relations: Evidence from the automotive

industry in Japan and the United States. Journal of

Economic Behavior & Organization, 34(3), 387–417.

Saris, W. E., & Gallhofer, I. N. (2014). Design, evaluation,

and analysis of questionnaires for survey research.

John Wiley & Sons.

Schreiner, M., Kale, P., & Corsten, D. (2009). What really

is alliance management capability and how does it

impact alliance outcomes and success? Strategic

Management Journal, 30(13), 1395–1419.

Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: the

nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise

performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13),

1319–1350.

Thomas, L. W., & Hunger, J. D. (2012). Strategic

management and business policy: toward global

sustainability. Columbus, Boston.

Tiantian, G., Yezhuang, T., & Qianqian, Y. (2014). Impact

of manufacturing Dynamic Capabilities on enterprise

performance-the Nonlinear Moderating effect of

Environmental Dynamism. Journal of Applied

Sciences, 14(18), 2067–2072.

Voola, R., & O’Cass, A. (2010). Implementing competitive

strategies: the role of responsive and proactive market

orientations. European Journal of Marketing., Vol. 44

No. 1/2, pp. 245-266.

doi:10.1108/03090561011008691

Wang, C. L., & Ahmed, P. K. (2007). Dynamic capabilities:

A review and research agenda. International Journal of

Management Reviews, 9(1), 31–51.

Wang, Y., & Rajagopalan, N. (2015). Alliance capabilities:

review and research agenda. Journal of Management,

41(1), 236–260.

Zheng, S., Zhang, W., & Du, J. (2011). Knowledge‐based

dynamic capabilities and innovation in networked

environments. Journal of Knowledge Management,

30(12), 1269-1290. doi: 10.1108/01443571011094262

Assessing Business Performance of the Traditional Market Trader: The Role of Buyer-supplier Relationship and Dynamic Capabilities

81