Internal Change Agents’ Strategies to Deal with Boundary in

Organizations in Indonesia

Leonardus Dewa Hardana

a

and Rayini Dahesihsari

b

Magister Psikologi Profesi, Atma Jaya Catholic University, Jalan Jendral Sudirman 51, South Jakarta, Indonesia

Keywords: Internal Change Agent, Boundary Spanning, Change Management.

Abstract: BACKGROUND: It is indicated that the role of internal change agent is increasingly important due to an

unforeseen future of post-covid era. However, studies about internal change agents are limited in contrast to

the work of external consultants. OBJECTIVE: This study aims to explore how internal change agents

perceived the permeability of boundaries in an organization and how the strategies they used to deal with such

boundaries. Boundary is among the specific challenges facing by internal change agents. METHODS: This

research applies qualitative approaches by conducting semi-structured interviews with six internal change

agents, using the maximum variation technique. RESULTS: The findings showed that structural, knowledge,

political, and interpersonal boundaries existed when participants managed change in organizations. However,

the characteristics of the perceived boundaries differed from what has been indicated in the previous studies,

particularly for the interpersonal boundaries. The findings also identified that internal change agents use

organizational support, communication, and invite participation to span the boundaries. CONCLUSION: The

findings contribute to literature related to boundaries to be spanned by internal change agents, particularly in

the specific context of Indonesia as a collectivistic and high-power-distance society, which have distinct

differences in nature and characteristics with previous studies in western countries.

1 INTRODUCTION

In every organization, change is a necessity. The

factors that influence change in organizations are very

diverse; according to Robbins & Judge (2017),

several external factors influence change, namely

competition, economic conditions and shocks,

technology, and social and political trends. According

to Heller (2002), if you ignore or underestimate

changing trends, the organization will suffer losses.

Therefore, for the sake of business continuity,

organizational change needs to be done. Change

management is a structured approach used to help

individuals, teams, and organizations to make a

transition from their current state to a new, better

condition (Coffman and Lutes, 2007)

The organization's need to change is currently

reinforced by two main factors, including the current

state of the industry, namely industry 4.0 and the

Covid-19 pandemic. Industry 4.0 itself is a current

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4125-2541

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7778-0573

industrial-style terminology that is present to replace

industry 3.0, characterized by cyber-physics and

manufacturing collaboration (Hermann et al., 2015).

Therefore, companies need to transform to be able to

adapt to the demands of industry 4.0. In addition to

the various demands of industry 4.0 with its digital

transformation, the Covid-19 pandemic that is present

worldwide at the beginning of 2020 is also a strong

accelerator of change (Li et al., 2021). Some of the

changes caused by the Covid-19 pandemic include

digital transformation, WFH work patterns,

downsizing, and many other changes that affect the

sustainability of the organization (Li et al., 2021).

When an organization decides to change, it is not

sure that the course of change in the organization will

take place smoothly and without resistance.

According to Maurer (2010), resistance can be

translated as fear, opposition, conflict, hassle, pain,

annoyance, anger, and suspicion that organizational

members perceive in the face of change. Therefore,

resistance to change needs to be managed in such a

388

Hardana, L. and Dahesihsari, R.

Internal Change Agents’ Strategies to Deal with Boundar y in Organizations in Indonesia.

DOI: 10.5220/0010752700003112

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences (ICE-HUMS 2021), pages 388-402

ISBN: 978-989-758-604-0

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

way that resistance shifts to readiness to change. The

term readiness to change refers to organizational

members' determination or joint commitment to

implement change and shared belief in their collective

ability to do so (Weiner, 2009).

In implementing change management to achieve

readiness for change, change agents play a crucial

role. Individuals or groups who carry out initiating

and managing change in an organization are known

as change agents (Lunenburg, 2010). Change agents

can also be interpreted as responsible for

implementing and encouraging change in the

organization (Palmer et al., 2017). The term change

agent usually refers to both internal and external

agents of change.

Generally, change agents are identical to experts

or external management consultants whom the

company pays to find out what is happening to the

company and implement changes to run optimally

(Palmer et al., 2017). However, over time the term

change agent also refers to an internal change agent.

In other words, change agents can also be internal or

come from within the organization, such as a manager

or employee appointed to oversee the change process.

Internal Change Agents (ICA) are one of the

spearheads of change management in organizations

because ICA plays a significant role in organizational

change, especially in implementing change

management strategies (Sturdy et al., 2016). ICA is

usually played out by H.R., managers, or other

organization representatives (Hartley, Bennington,

and Binns, 1997; Meyerson & Scully, 1995).

However, ICA can also be played out by mixed staff

from various levels and departments (Randall et al.,

2019). According to Smither et al. (2016), there are 4

advantages of ICA in implementing change compared

to external change agents, include: 1) ICA already

knows the work environment so that it takes less time

to adapt to the organization; 2) ICA knows and has a

close relationship with members of the organization

who will be the target of change; 3) ICA has more

access to workers who will be targets of change, as

well as their superiors; and 4) using ICA is a more

efficient option in terms of costs compared to outside

consultants.

In implementing change in an organization,

change agents will cross boundaries (boundary

spanning or boundary work) between groups and

individuals in cross-job (Schotter, Mudambi, Doz,

and Gaur, 2017). ICA can also be referred to as

"boundary-shakers" (Balogun, 2005). How to change

agents work is influenced by how they perceive the

boundaries of the changes they see and experience in

the organization (Randall et al., 2019). Wright (2006)

argues that when changes occur, uncertainty arises.

This uncertainty then makes the change agents feel

ambivalent or confused about whether they are

"insiders" (being part of the organization) or

"outsiders" (not members or from outside the

organization).

This condition raises challenges to ICA in 4

dimensions/aspects of the boundary. According to

Wright (2009), four boundaries commonly found by

ICA include: 1) roles and positions in the hierarchy

(structural boundaries), 2) expertise and functional

activities (knowledge boundaries), 3) legitimacy and

organizational power (political boundary); and 4)

personal relationships with clients (interpersonal

boundaries). According to Orlikowski (2002), seven

boundaries can be perceived subjectively by ICA,

including 1) temporal boundary; 2) geographic

boundary; 3) social boundary; 4) cultural boundary;

5) historical boundary, 6) technical boundary, and 7)

political boundary. Meanwhile, according to Palus et

al. (2011), there are five types or categories of

boundaries, including 1) Vertical, including rank,

class, seniority, authority, and power, 2) Horizontal,

including skills, functions, colleagues, and

competitors, 3) Stakeholders, including

partners/partners, constituencies, other business

chains, and communities, 4) Demographics,

including gender, religion, age, nationality and

culture, and 5) Geographical, including location, area,

type of market, and distance.

In terms of managing change, boundaries can be a

challenging factor for implementing change because

boundaries can separate organizational members into

"us" and "them" categories, which can lead to

conflict, direction, fragmentation, misalignment, and

lack of commitment (Palus et al., 2011), in this case,

it means commitment to implementing change.

Boundary overcoming strategies can be interpreted as

steps for organizational members to build and manage

interactions with other people in companies outside

their workgroups or direct teams (Ancona, 1990;

Ancona and Caldwell, 1992; Marrone et al., 2007).

In general, Palus et al. (2011: 481) illustrates

strategies to overcome boundaries into 6 types of

strategies, including: 1) buffering, which means

efforts to monitor and protect the flow of information

and resources between groups to determine

boundaries and create a sense of security, 2)

reflecting, which means efforts to represent different

perspectives and facilitate the exchange of knowledge

between groups to understand boundaries and foster

respect, 3) connecting, which means efforts to

connect members and bridge groups that are divided

to remove boundaries and build trust, 4) mobilizing,

Internal Change Agents’ Strategies to Deal with Boundary in Organizations in Indonesia

389

to creating goals and common identities across groups

to change (reframe) boundaries and develop a shared

community, 5) weaving, in the form of efforts to

integrate group differences into a larger overall

context to link boundaries and create a sense of

interdependence, and 6) transforming, which is an

attempt to unite several groups together by setting

new goals and directions to overcome boundaries so

as to allow new discoveries to emerge.

While implemented in the Indonesian context,

boundary-spanning activities and change

management dynamics can be unique due to their

cultural and contextual aspects. Indonesia has

demographic diversity in ethnicity, religion, race,

culture, and groups (Pusat Data dan Statistik

Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, 2016). The existence of

Indonesian contextual characteristics, either directly

or indirectly, will affect how employees or members

of the organization work and behave (Mulyaningsih,

2020). External conditions that organizations must

face, including markets, customers, technology,

shareholders, government regulations, culture, and

social values in which the company operates, also

affect the habits that will be adopted in the

organization. This is supported by findings from

Silalahi (2017) that the habits of organizational

members are formed from the values, norms,

assumptions, beliefs, and systems adopted by

organizational members who are affected by the

broader culture in the environment in which they live

together. Furthermore, Sagiv & Schwartz (2007)

stated that national and individual values and cultures

could influence habits in organizations, or

furthermore can be interpreted as organizational

culture. Organizational culture is a pattern of beliefs

and expectations held by members of the organization

to produce strong values to shape the behavior of

individuals or members of the organization (Schwartz

and Davis, 1981). Some of the prominent

characteristics of Indonesian culture are represented

by the dimensions of Indonesian culture with

collectivistic values and high power distance

(Hofstede, 2010). supported by the opinion of Sagiv

& Schwartz (2007) that national culture can affect

organizational culture, then this is confirmed through

the findings of several studies on organizations in

Indonesia that have high collectivistic values and

power distance characteristics.

The uniqueness of Indonesia as a context can be a

support or even become more challenging for ICA to

deal with boundaries. One example, organizations in

Indonesia are generally bureaucratic and have a

formal and distant organizational structure (Nugroho,

2013). Furthermore, the characteristics of

bureaucratic organizations are usually labelled as

"reluctant to change" and "avoiding risks", including

for their excellence (Nugroho, 1999; Nugroho, 2010).

This is supported by the research of Muhammad

(2005), who concluded that an organizational

structure that is too mechanistic affects the high level

of difficulty of boundary-spanning activities in

organizations in the work environment of auditors. It

could be that the characteristics of this bureaucratic

organization are related to the cultural dimensions of

Indonesia's high power distance, referring to

Hofstede's (2010) theory of cultural dimensions.

So far, researchers have not found many studies

on boundary spanning activity (BSA) conducted by

ICA in organizations in Indonesia concerning change

management. Previous studies that the researchers

managed to find were several studies on boundary

spanning activity (BSA) conducted by organizations

in Indonesia but not explicitly related to change

agents in managing change. The peculiarities of ICA

are mostly related to boundary spanning, that is, being

in an ambivalent situation, namely being part of a

member of an organization that is changing on the one

hand, but must be a mover of change so that it seems

to take a role outside the organization This role as

insiders and outsiders at once is one of the typical

characteristics of ICA (Wright, 2006; in Randall

2019). As done by Yustiarti et al. (2016) in the

context of the auditor's work environment, previous

studies found that individuals who carry out

boundary-spanning activities can experience role

stress or stress caused by role conflict. Role conflict

as a boundary can arise because change agents played

two or more roles and orders that are consecutive but

inconsistent (Yustiarti et al., 2016). Worldailmi &

Hartono (2018) also found that middle managers in

projects with a context in Indonesia experienced

several boundaries, involved 1) vertical boundaries to

cross levels and hierarchies both upward

(superordinate) and downward (subordinate); 2)

horizontal boundaries in passing the relationship

between functions and expertise; 3) stakeholders

from outside the company or with external partners;

4) demographic in crossing differences between

groups including personal differences such as gender,

education, and ideology; 5) geographic in crossing

the boundaries of distance, location, culture, area, and

market. As for the context of work units in hospitals

in Indonesia, according to Sari & Wulandari (2015),

the boundaries found include the large size of the

organization, the number of units, and the difficulty

of coordination between units.

Based on the ideas as mentioned earlier, we aimed

at exploring (1) the boundaries facing by ICA in

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

390

managing change in an organization and also (2) the

strategies used to deal with the boundaries.

Companies can use this to find the most appropriate

way to prepare and develop ICA as a significant

driver in managing change.

2 METHODS (AND MATERIALS)

The present study pursues the following research

questions:

• RQ1:

What are the boundaries experienced by

Internal Change Agents (ICA) in

organizations in Indonesia?

• RQ2:

What strategies do they use to span these

boundaries to manage change effectively?

A descriptive qualitative approach was used in

this study to explore the perceptions and experiences

of participants in dealing with boundaries during their

roles as internal change agents because they have

personal experience in implementing change

strategies in their organization. Corley, Gioia, and

Hamilton (2013: 17) argue that people who construct

their organizational reality will know what they are

trying to do and can explain their thoughts, intentions,

and actions. The data was obtained from semi-

structured interviews with the purposive sampling

technique to obtain rich insights and information

(Neergaard et al., 2009; Sandelowski, 2000).

2.1 Research Variables

The variables of this study are (1) Boundaries

experienced by ICA in organizations in Indonesia and

(2) Strategies being used by ICA to span these

boundaries. According to Smither et al. (2016), the

boundary can be defined as a rigid and complex to

penetrate boundary that usually takes the form of a

system, bureaucracy, and interactions between

members or sub-groups. The strategy for spanning

boundaries can be interpreted as steps for

organizational members to build and manage

interactions with other people in companies outside

their workgroups or direct teams (Ancona, 1990;

Ancona and Caldwell, 1992; Marrone et al., 2007).

The peculiarities of the Indonesian context with

demographics consisting of various ethnicities,

religions, races, cultures, and groups (Pusat Data

Statistik Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, 2016), also, the

characteristics of the Indonesian cultural dimensions

include high power distance and collectivity

(Hofstede, 2010) might directly or indirectly

influence the way employees to do their job and

behave as members of the organization

(Mulyaningsih, 2020). These contextual peculiarities

might also shape the uniqueness of the nature and

characteristics of the boundaries experienced by ICA

in organizations in Indonesia and the choices of

strategies they use in overcoming the boundaries to

manage change effectively.

2.2 Participants

The population group in this study are employees or

organizational members who act as internal change

agents (ICA) in an organization in Indonesia that has

been successful in implementing a change strategy.

This study has targeted participants who have the

following characteristics:

1. Employees of a company or active members

of an organization.

2. Productive age (15-64 years), based on the

productive age category by Badan Pusat

Statistik Indonesia.

3. Appointed or taking the initiative to become

an internal change agent (ICA) in the company

or organization.

4. Has finished carrying out their role as ICA in

implementing change, and has been

successfully manage the organizational

change effectively.

5. Indonesian citizenship, and working for

organizations in Indonesia.

The sampling technique used was the maximum

variation sampling which is a sample selection

technique to obtain and describe the main theme of

the variety of participants who are representations of

the population (Patton, 2002: 53). The principle of

maximum variation sampling is that when researchers

interview very different choices of participants, their

answers can be closer to the answer to the entire

population (Patton, 2002). The variations of

participants that were taking into consideration were

the type of industry, work position, work area,

gender, age, and educational background of the ICAs.

2.3 Data Collection and Analysis

Boundary spanning is a very psychological and

personal experience, so a qualitative approach, not a

quantitative one, was chosen to explain the subjective

phenomena experienced by the participants.

Qualitative data was collected using semi-structured

interviews, in which participants are instructed to

Internal Change Agents’ Strategies to Deal with Boundary in Organizations in Indonesia

391

answer pre-defined open-ended questions. The

interview guidelines involved topics that need to be

explored: (1) ICA experiences on the organizational

change process; (2) boundaries encountered during

the process of managing change; and (3) strategies

implemented in spanning boundaries.

Data were analyzed using thematic analysis

methods. The thematic analysis identifies patterned

themes in a finding/phenomenon (Boyatzis, 1998).

These themes can be identified inductively (data-

driven) from raw qualitative data in the form of

interview transcripts (Boyatzis, 1998). The

interviews were all recorded as audio and were

transcribed as written documents. Using an inductive

approach to code the data (Berg, 2017), data was used

to develop the code and identify meaningful themes.

After that, the data was linked to the theoretical

framework of Wright (2009) and Palus et al. (2011)

as references. The two authors then discussed the

findings and the disagreement issues on meaningful

coding and themes. This process would ensure the

credibility of the results, based on triangulation of

data analyses (Patton, 2014). The rationality of the

findings and conclusions also can be re-verification

that refers to the raw data.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 The Profile of Participants

Six ICAs participated in this study. They came from

six different organizations with an age range from 30

years to 59 years old. Three of the participants were

male, while the other three of them were female. The

details of their profiles are listed in Table 1.

3.2 Boundaries Experienced by ICA in

Managing Change

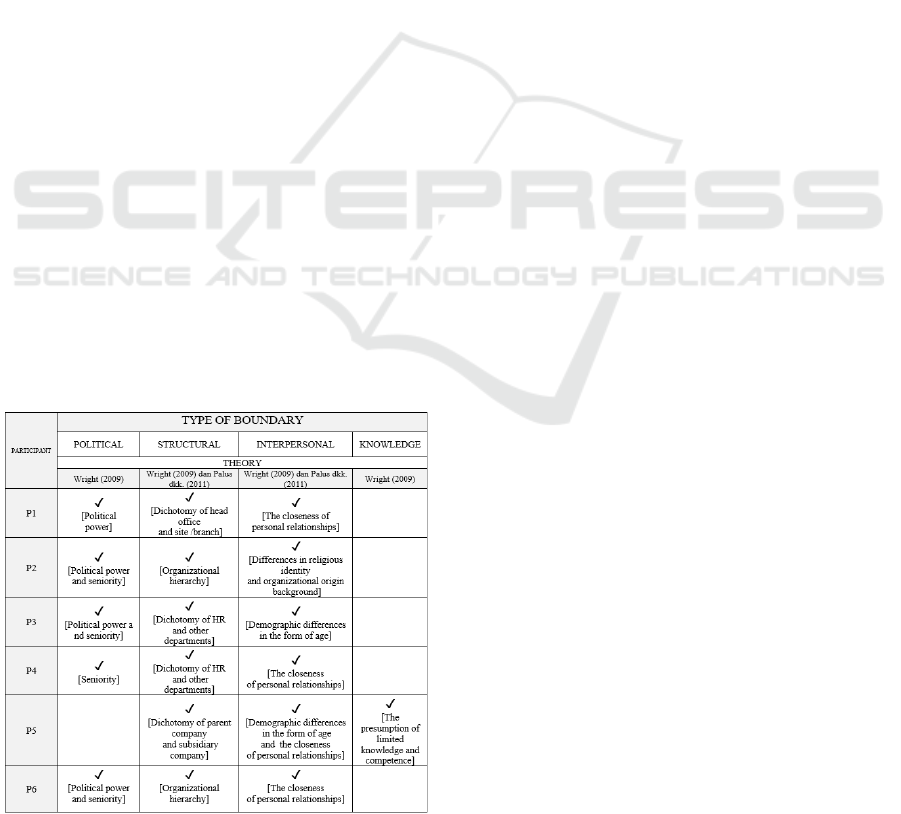

As shown in Table 2, the findings showed several

boundary similarities found by the six participants in

carrying out their role as internal change agents. Four

of the six participants experienced boundary in the

form of limited political power. In addition, four of

the six participants shared the exact boundaries in the

form of seniority. Furthermore, the structural

hierarchy in the organization is experienced as a

boundary by two of the six participants. Five out of

the six participants experienced the differentiation of

the structural functions of the department and the

nature of the organization (e.g., head office branch,

H.R. department-non H.R. department, and parent-

subsidiary companies). The closeness of personal

relationships was also recognized as a boundary by

three out of six participants. Three out of six

participants also experienced demographic

Table 1: Participants’ profile.

Participant Industry ICA Role Organizational Change Position in organization

P1 Coal Mine Implement Change

KPI Changes of Mine

Operators

Operation Development

(Section Head)

P2

Education

(University)

Initiate & Implement

Change

Initiate Student as

Practicum Assistant

Head of Master Study

Program

P3

Cruise and

Shipping

Implement Change

Changes in Staffing and

Work Patterns

HR Recruitment &

Organization People

Development Assistant

Manager

P4 Mine

Initiate & Implement

Change

Recruitment Phase

Change

Talent Acquisition Junior

Manager

P5 Travel Agency Implement Change

Business and Sales

Optimization

Vice President Sales and

Marketing

P6 Air Line Cargo Implement Change

Business Optimization

and Data Based Work

Process Changes

Vice President

Transformation

Management

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

392

differences. Meanwhile, the boundary is in the form

of perception/assumption that one participant,

(participant 5) only experience the limited knowledge

and competence possessed by the agent of change.

Therefore, based on data obtained from interviews

with the six participants, it was found that there are

some similarities in the boundary they experience in

carrying out their roles as internal change agents.

There have been several previous studies that

classified the types or aspects of the boundary.

However, looking at the boundary patterns found

from the six participants, the most representative

boundary classification and describing the boundary

realities encountered by participants is the one

initiated by Wright (2009). The argument is based on

the researchers' analysis that the seniority in the

boundary classification of Palus et al. (2011) can be

categorized as a political boundary because it creates

an impression of a political power gap. Likewise,

demographic boundaries (age, origin, and religion)

found in participants can be categorized as

interpersonal boundaries because demographic

boundaries create social distance gaps between agents

of change and change targets. The rest, what is

clearer, are structural boundaries related to roles and

positions in the hierarchy and political boundaries

related to legitimacy and organizational power and

the impressions that grow therein. When referring to

the boundary classification by Wright (2009),

participants found four types of boundaries, namely

political, structural, interpersonal, and knowledge

boundaries. The four types of the boundary are

summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Types of boundaries experienced by the

participants.

3.2.1 Structural Boundary

From the boundary table (table 2) found in the six

participants above, it can be seen that all participants

have structural limitations in acting as internal change

agents. This finding confirms several aspects of the

boundary that have been found in several previous

studies, such as in Wright (2009), with the naming of

vertical boundaries in Palus et al. (2011). The finding

also confirms that the position and level in the

organizational structure will determine the success of

ICA in implementing change. Thus, all participants

experienced structural boundaries.

Based on qualitative information obtained from

the six participants, apart from being related to the

position, structural boundaries also tend to be

interpreted as representing parties or the roles played

by internal change agents. Internal change agents can

be viewed as coming from the head office, the parent

company, the H.R. department, and top-level

management. Four structural boundary dichotomies

were found from the six participants, including 1) the

head office and branch dichotomies, 2) the parent and

subsidiary dichotomies, 3) the H.R. and non-HR

department dichotomies, and 4) the differentiation of

upper, middle management, and down. Those four

dichotomies found in participants as shown below:

Excerpt 1

"Because the head office always brings some kind of

improvement, the language that is already common in

the field is improvement. Like that kind of stigma is

not a strange thing, you know. ‘There must be a new

program here’, something like that"

(P1, male)

Excerpt 2

"because of GI (initial of parent company) employess

are just assistance employees. So, GI employees

(initials) who are assigned to AGI (initial of

subsidiary company) are full of many rumors, such as

the assisted employees from GI (initials) have higher

salaries than the original employees of AGI. There

are a lot of rumors. So there are also several

reluctants from AGI employees"

(P5, female)

Excerpt 3

"Like ‘oh no, not HR again’. Like no one likes HR

people. Because HR is about policies, roles,

procedures, so it's normal for people not to like us. So

when they are about to interact with HR people, they

become uninterested"

(P4, female)

Internal Change Agents’ Strategies to Deal with Boundary in Organizations in Indonesia

393

Excerpt 4

"So I can't appear face to face in the district as I am

an employee in the management services group

leader, because my level is not that high, actually"

(P1, male)

Categorization of these differences and

boundaries comes complete with the perceptions and

stigma behind the assessment between groups. The

thought "they are not part of us" is the main thinking

theme that derives from the structural boundaries

experienced by the six participants.

3.2.2 Political Boundary

The second boundary found in 4 out of 6 participants

is the political boundary. Political boundary are

obtained from impressions that usually arise from the

legitimacy of political power over a certain

position/level in organizations, as shown below:

Excerpt 5

“They clearly know that I am not a close person to

the Board of Directors level. No, no, because I wasn't

on that high level. So it really needs that impression

and power"

(P3, male)

The findings showed there is a possibility that the

structural position is also related to the legitimacy of

power that allows change to be carried out. The

higher a person's position in a company or

organization, they may have the more power to

provide and carry out the direction for change. Hence

usually, the strategy taken to span this boundary is

supported by a higher level of internal change agents

who play a direct role. Discussions about this strategy

will be discussed in more detail in the next sub-

chapter.

Palus et al. (2011) also suggested the vertical

seniority boundary, which is more generally

categorized as the political boundary by Wright

(2009) and is recognized by the participants as a more

limitation or challenge in implementing change. The

assumption/label "junior" pinned on internal change

agents by change targets with longer tenure (seniors)

than them is considered a significant challenge to

managing change. That junior is required unwritten to

respect seniors is a significant qualitative data related

to the context and peculiarities of organizations in

Indonesia. Seniority as political boundary shown in

these excerpts below:

Excerpt 6

“Because at that first time I was indeed the youngest.

Then maybe there is also a judgement, because young

people talk about a lot of ideas and suggestions,

maybe some some of them didn’t like me.”

(P2, female)

Excerpt 7

"So yes, at the beginning I was underestimated or

gossiped about. Wow, being gossiped is certain, that's

for sure. ‘That’s a new kid, right?’”

(P4, female)

This structural and political boundary may

confirm findings in previous research in Indonesia

that organizations in Indonesia are generally

bureaucratic and have formal and distant

organizational structures (Nugroho, 2013). Other

studies also say a negative relationship between the

level of effectiveness of boundary spanning and the

organizational structure of the audit team on research

conducted by Muhammad (2005). Although

specifically and explicitly stated that this is not

related to one of the dimensions of Indonesian culture

as Hofstede (2010) proposed, namely high power

distance, it could be that it has a possible relationship.

A high boundary in the form of a mechanical

organizational structure is also related to providing

and conducting change directions, so it is also related

to high power distance.

3.2.3 Interpersonal Boundary

Another boundary that also appeared in all

participants apart from structural boundaries was the

interpersonal boundary. This interpersonal boundary

is a demographic boundary when referring to the

classification of Palus et al. (2011), because

demographic differences result in differences in

social identity and make social distance gaps.

Participants recognized that in leading and

implementing change management, efforts were

needed to reduce social distance, recognize, and

approach themselves more personally to carry out

their role as ICA. The participants also recognize

personal relationships as one of the boundaries they

encounter. Without any effort to get closer personally,

the change targets will show resistance to change. The

finding confirms the boundary aspect in the form of a

personal relationship with the client (interpersonal

boundary), which was suggested by Wright (2009).

The finding, however somewhat different from the

findings in Randall's (2019) study with the context of

participants in the United Kingdom and Australia

who said that interpersonal boundaries are defined as

informal relationships as one of the boundaries, so

ICA is advised to have a formal relationship with the

target of change.

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

394

On the other hand, it is precisely in Indonesia that

personal and informal relationships are needed. In

addition, this boundary can also be classified as a

social boundary when referring to the classification

proposed by Orlikowski (2002), or it can also be

referred to as a horizontal boundary according to

Palus et al. (2011). Evidenced by the classification of

3 different initiators, it can be concluded that

interpersonal relationships can be categorized as

boundaries in the context and peculiarities of

Indonesia represented by the participants in this

study. When referring to the dimensions of

Indonesian culture as proposed by Hofstede (2010), it

could be that the context and peculiarities of

Indonesia and its high collective character affect

interpersonal boundaries. Personal relationships are

considered necessary to implement change, and

internal change agents demanded to be "personally

close" to the change target. As put by participant 5:

Excerpt 8

"So if you want to implement the changes you have to

be close first, we have to be friends first. ‘Who are

you anyway? Why you want to organize us if you’re

not familiar with us yet?’"

(P5, female)

Still a category with interpersonal boundaries,

demographic differences were also experienced by

participants in this study. In the qualitative data

obtained from the participants, three demographic

boundaries were found, namely age, religion, and

origin. Particularly for "origin", the boundary referred

to is the origin of former university/organization

experienced by participant 2, who forms a separate

identity in their working life at the university

(educational organization).

Although it was explicitly conveyed and

experienced by only 1 participant (participant 2),

apart from the demographic boundary of origin (home

university), another identity that forms the boundary

is religion. As a member of an organization with a

different belief/religion from the majority of other

organizations, participant 2 acknowledged that this

affects the ability to implement change and determine

strategic planning in the organization. There is a

tendency for this boundary also to give birth to a

majority-minority religion dichotomy. These findings

also confirm the demographic boundary classification

proposed by Palus et al. (2011). As participant 2 put

it:

Excerpt 9

"First is a minority, from a minority religion. When it

comes to religion, I am the only one who is Catholic.

Another one is Christian (protesant), the rest are

Muslims. The second is that I came from the alumni

who are not from the alumni where I work. Yes those

what make it hard, because I was different"

(P2, female)

Another interpersonal-demographic boundary

that is acknowledged to be experienced by more

participants is the age demographic boundary. The

participants recognized the significant age difference

between the internal change agent and the change

target as a limitation or challenge for managing

change. At a more macro level within the company,

this age difference by participants is also expressed

by the mention of "generational differences".

Generational differences also need to be spanned

because organizational members may consist of more

than one generation. In 2 participants (in participants

2 and 5), they also linked age differences with

political boundaries, especially seniority. Age

difference as boundary illustrated in the description

below:

Excerpt 10

"Because we’re not friend, more so because of the

gap, gap in age. So some of general managers’ age

are already 50. Moreover, there are those who are

the same age as my mother. Then suddenly I came in

as their boss. So sometimes personally, I believe they

feel that’s weird, me too”

(P5, female)

Based on the qualitative data obtained in this

study, the demographic background that causes

differences in identity and creates social distance is

illustrated as an interpersonal boundary in the

Indonesian context. Political boundaries in the form

of seniority also seem to be the boundaries found by

ICA in Indonesia. Therefore, it could be that political

boundaries, especially seniority, and interpersonal

boundaries, especially demographic differences and

the character of a collective society, are boundaries

that arise because of the uniqueness of the Indonesian

context.

3.2.4 Knowledge Boundary

In addition to the three boundaries previously

discussed, the last boundary found in participants was

the knowledge boundary. Even though it was

explicitly conveyed by only 1 participant (participant

5), actually, the knowledge boundary could be related

to the political boundary (seniority).

According to them, the assumption of

"new/junior" is also related to the assumption that

Internal Change Agents’ Strategies to Deal with Boundary in Organizations in Indonesia

395

internal change agents do not know to manage

change, nor do they know the company's context for

making change. Participant 5 also feels this limited

knowledge comes from her much more senior

subordinates (who have a more extended working

period) than her. The knowledge boundary illustrated

by the excerpt below:

Excerpt 11

"Because I am new, right? When new people come to

decide on a strategy without bringing evidence or

facts, the data is definitely considered as nonsense,

right? Suddenly made. So that's why we have to

explain the background data, why we made this

decision because of this background"

(P5, female)

3.3 Strategies to Span Boundary

In managing change in organizations, internal change

agents will penetrate boundaries (boundary spanning

or boundary work) between groups and individuals in

cross-work (Schotter, Mudambi, Doz, and Gaur,

2017). According to Smither et al. (2016), the

boundary itself can be interpreted as a rigid and

complex to penetrate boundary that usually takes a

system, bureaucracy, and interactions between

members or sub-groups in the organization. In its

development, the term boundary spanning is now

widely used to describe a situation where a person

crosses social group boundaries (Matous and Wang,

2009). In addition, strategies to overcome boundaries

can also be interpreted as steps for organizational

members to build and manage interactions with other

people in companies outside their workgroups or

direct teams (Ancona, 1990; Ancona and Caldwell,

1992; Marrone et al., 2007). So as an internal change

agent, the four boundaries that are owned and

experienced by ICA need to be spanned. In spanning

the boundary, ICA tends to have specific ways or

strategies. Likewise, with the six participants in this

study.

Participant 1 spanned boundaries by seeking

higher-level support, utilizing informal leaders,

approaching change targets personally, and

supporting data. Furthermore, participant 2 attempted

to approach personally to minimize social distance

and use the legitimacy of structural positions and

political power. Participant 3 implements several

steps, namely completing administrative documents

as support in implementing change, creating a change

support system based on benefits and promotions, and

seeking higher-level support to help them manage

change. The strategy adopted by participant 4 was to

seek support at a higher level, approach personally,

and use an accommodating communication style.

Participant 5 implements several strategies, namely

seeking higher-level support, building a reward and

punishment system, discussing and approaching

personally, and providing data supporting change.

Finally, participant 6 implemented several steps to

overcome the boundary, namely seeking higher-level

support, using an accommodative communication

style, conducting two-way discussion and

communication, and involving change targets in the

planning and implementation process.

This data indicated that some participants used the

same strategies as other participants. However, in

addition, if the researchers analyze the data based on

several common features, actually some of the steps

that the participants use to span these boundaries can

be summarized into three main strategies, including:

1. Organizational Support

This strategy is not fully carried out by ICA

personally, but requires organizational

support. This strategy is carried out to span the

boundary that comes from both structural

hierarchy and the impression of differences of

organizational political gaps between change

targets and ICA. Organizational support that

can be provided in carrying out this strategy

can be in the form of support systems (such as

benefits, rewards, and punishment for

managing change), directions from higher

levels, and political power obtained from

higher structural positions.

2. Invite Participation

This strategy is carried out to tackle identity

differences caused by structural hierarchical

gap between ICA and change targets by

inviting/fostering participation and

involvement of change targets. Practical ways

that can be used, for example, are efforts to

involve change targets in the process of

planning and implementing change, as well as

using informal leaders of change targets as a

link between ICA and change targets.

3. Communication

This strategy includes efforts to communicate

and facilitate the exchange of different

perspectives between ICA and change targets.

Communication strategies are used to break

boundaries that come from social and

interpersonal distance, structural and political

gap, as well as the assumption of limited ICA

knowledge and skills. Some steps that can be

taken in implementing a communication

strategy are understanding the uniqueness of

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

396

the context and characteristics of change

targets, making efforts to approach change

targets personally, using accommodative

communication style or similar-level

communication, and discussing or

communicating in two directions to exchange

perspectives and absorb input from the change

targets, and also communicating data

supporting change.

Researchers have not found previous research and

literature on boundary spanning classification and

research that links specifically between boundary

coping strategies and change management carried out

by ICA. However, in general, Palus et al. (2011: 481)

categorizes strategies to overcome boundaries

(without relation to change management) into six

strategies, namely: 1) buffering, 2) reflecting, 3)

connecting, 4) mobilizing, 5) weaving, and 6)

transforming. When referring to the specific

definition of each strategy put forward by Palus et al.

(2011) and looking at the data patterns of the

boundary-spanning strategies carried out by the six

participants, the researchers concluded that some of

the strategies were similar and representative to

illustrate the choice of steps or strategies taken by the

participants. Three strategies can be categorized using

strategies to overcome the boundaries by Palus et al.

(2011), but some are not covered. For example, a

communication strategy can be classified as a

buffering, reflecting, connecting, and mobilizing

strategy with similar definitions and characteristics.

Likewise, the strategy of inviting participation has

similarities with the weaving and transforming

strategies. However, the organizational support

strategy does not have specific similarities with the

six strategies because it is not a personal effort of ICA

but it manifests in the form of organizational support.

From the description of each strategy, it can be

seen that one strategy can be used to span one or more

boundaries. For example, political boundaries can be

spanned by organizational support strategies and

communication strategies. Furthermore, structural

boundaries can be overcome by invite participation,

organizational support, and communication strategy.

Finally, the interpersonal boundary and knowledge

boundary can be spanned with a communication

strategy. Details of 3 general categories of strategies

to overcome boundaries based on the types of

boundaries experienced by the participants in this

study can be illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Boundary overcoming strategies based on

boundary type.

3.3.1 Organizational Support

The organizational support strategy is not a personal

effort of an ICA but rather the assistance provided by

the organization to support ICA in overcoming

structural and political boundaries.

Political boundaries are overcome, penetrated, or

spanned by participants using organizational support

strategy and communication strategy. On the six

participants, steps are taken explicitly by seeking

support from the board of directors or top

management, using the legitimacy of structural

positions and higher power, and creating a change

support system (such as benefits, reward &

punishment, and administrative completeness) as

shown below:

Excerpt 12

“So if there are some obstacles with the team, maybe

if the team really can't support it, then I'll escalate it

to my superiors. What should we do, is there a

rotation or what. Still, there must be intervention

from the Director. Because the highest level is the

Director. So if the Board of Directors or our

superiors contradict our vision, it's definitely not

going to work"

(P6, male)

Excerpt 13

"And I went from below, then became a manager,

then became a senior manager, then became VP,

moreover VP transformation management, right?

The ones who will do these changes. That may be

what makes it more acceptable. "

(P6, male)

Internal Change Agents’ Strategies to Deal with Boundary in Organizations in Indonesia

397

Excerpt 14

"Yes, otherwise it would be messy. If we are not neat

administratively we will not be able to. The system

must be neat administratively”.

(P3, male)

From the results of interviews with the six

participants, it was found that there is a possibility

that the structural position is related to the legitimacy

of power that allows change to be carried out. This

means that the higher the position of a person in a

company or organization, it could be that they have

the power and political impression that allows them

to provide and carry out the direction for change.

Then, it makes sense that the strategy undertaken to

span these structural and political boundaries is with

support from a higher level of change agents who play

a direct role. Of course, the legitimacy of the

structural position and higher power can also be used,

but this is more difficult to do because if the power of

the agent of change is still relatively low, then he

needs to wait to have a higher power obtained from a

higher structural position than the one now he has

this. Meanwhile, the third step, namely creating a

change support system (such as benefits, reward &

punishment, and administrative completeness) is

carried out to compensate for the power possessed by

change agents in implementing change.

3.3.2 Invite Participation

An invite participation strategy is carried out to tackle

structural boundaries by inviting/fostering

participation and involvement of change targets. All

of the participants experienced structural boundary;

hence, the efforts they used to span this boundary are

involving change targets in planning and

implementing change and using informal leaders of

change targets as a link between ICA and change

targets. For instances:

Excerpts 15

"Because they can protest ‘we were never invited to a

discussion, then ended up being decided!. So they feel

they are not part of this movement. We just follow

orders from superiors. They want more participation,

not just as perpetrators. But they want to be invited to

a discussion as well to get involved further to

contribute their thoughts. When they speak up, they

talk to themselves in front of the forum, it will be

stronger. Once they have made a self-spoken

contribution, then they will take responsibility.

(P6, male)

Excerpts 16

"Yes, it is the most eldest person, the most vocal

person. So we have approached it, we even made

them as change agent team as well. So that they make

it easier for us to enter all groups at the operator

level. Those who we are approaching"

(P1, male)

Differences in hierarchy, structure, function, role,

and department are structural boundaries that will

create a group identity gap. This difference in group

identity will then lead to perceptions and stigma

between groups, ICA, and the target of change. The

thought "they are not part of us" is the central thinking

theme that derives from the structural boundaries

experienced by the six participants, hence involving

change targets in the planning and implementation

process and empowering informal leaders are three

steps to breaking the structural level and trying to

create a bridge between ICA and change targets.

3.3.3 Communication

From the three strategies found, communication

strategy can be used to span the four types of

boundary. Communication can be used to overcome

political, structural, interpersonal, and knowledge

boundaries. This strategy is possible because in

spanning boundaries, the basic principle is that both

parties, in this case, ICA and the target of change,

need to understand each other. Hence,

communication strategy enables ICA to communicate

and facilitate the exchange of different perspectives

between ICA and change targets.

The political boundary that arises specifically for

ICA with shorter tenure is spanned using a

communication strategy, namely by carrying out

accommodative communication and approaching

personally to minimize social distance and bridge

tenure differences with the change targets.

Excerpt 17

“Moreover, they are alredy senior. So I have to

approach them and begging for help. From that point

they feel they have a responsibility to develop the

company in this function. They already know that the

recruitment isn’t good at the company and I said 'I

need help'. So it will be a different story if I patronize

them 'It has to be like this like this!'. Not like that, whe

need to begging for help"

(P4, female)

Relatively the same as the political boundary, in

spanning structural boundary, participants conducted

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

398

two-way communication to exchange perspectives

for breaking the hierarchical structural level and

creating a bridge between ICA and change targets.

Excerpt 18

"Yes, there was always discussion. So that the gap is

reduced. So they know what we mean. We also know

what they want, as well what is still annoying them"

(P3, male)

The boundary that was also experienced by the

participants in this study in carrying out their role as

ICA was the interpersonal boundary. Participants

recognized that in leading and implementing change

management, efforts were needed to reduce social

distance, recognize, and approach themselves more

personally to carry out their role as ICA. The

qualitative data obtained from these participants can

explain the reasons why ICA chooses a

communication strategy, especially with four steps to

span interpersonal boundaries, namely understanding

the context and characteristics of change targets,

making two-way communication to exchange

perspectives, approaching personally, and making

accommodative communication, as stated below:

Excerpt 19

"Okay, my advice is that know your business well,

also get to know personally the general character of

the people in the company. Companies have

character. There is value that the company has. So we

should have the power to recognize there, so that

when we implement it we can have a strategy to

interact with them based on what kind of person like

are they.”

(P3, male)

Excerpt 20

"Discussions, try to get closer to each other

personally too. In a meeting, it is more formal when

it comes to discussing business issues, for example in

the office. But if you want to know more personally, I

can usually invite you to eat together"

(P5, female)

Excerpt 21

"Yes, true. 'What can I do to help?’ Then they will be

able to open up to give everything. Because if I

communicate as if I came from above, the command

is like this, do it! Yes maybe they will do but it's

forced"

(P1, male)

Interpersonal boundaries can also arise due to

differences in demographic backgrounds. For

example, in the information obtained from interview

data with participants, at least three demographic

differences were found, namely age demographics,

religious demographics, and demographic identity of

origin. Moreover, these three types of demographic

differences seem to provoke cross-group "identities",

complete with the perceptions and judgments of one

group. Hence, seeing the existing data patterns, ICA

will carry out several approaches to span age

demographic boundaries, namely trying to

understand the context and characteristics of change

targets, making two-way communication to exchange

perspectives, reducing social distance or approaching

change targets personally, and implementing

accommodating communication.

The last boundary experienced by ICA is the

knowledge boundary. Based on the qualitative data

obtained, this boundary is related to the assumption

that change agents do not know to manage change,

nor do they know the company's context for making

change. This assumption of not knowing can be

answered by implementing a communication strategy

by providing and communicating data supporting

change. Using this strategy, the doubts and antipathy

of change targets to ICA related to the assumption

that ICA's limited knowledge in managing change

can be minimized. As participant 5 put it:

Excerpt 22

“So that's why we have to provide the background

data, why we made this decision because of this and

this”

(P5, female)

Based on the data obtained from the six

participants, it was found that ICA's strategy to span

boundaries in the Indonesian context may also have

specific characteristics. Participants experienced

structural and political boundaries, but in fact, they

also experienced interpersonal boundaries. It could be

a structural and political boundary due to the high

power distance character represented by the cultural

dimensions of Hofstede (2010) in the Indonesian

context. The interpersonal boundaries encountered

may be due to the high character of collectivistic (low

individuality) represented by the cultural dimensions

of Hofstede (2010). The dynamics of these

peculiarities cause ICA to have a certain legitimacy

of structure and power, but on the other hand, it also

needs to be close personally and informally with the

target group for change to foster trust among them

(Wright, 2009). It seems that high collectivity is also

related to a high value of togetherness so that a sense

Internal Change Agents’ Strategies to Deal with Boundary in Organizations in Indonesia

399

of wanting to be involved and to be heard needs to be

facilitated.

3.4 Characteristics of ICA Needed to

Span the Boundary

In addition to the strategy to span the boundary that

was carried out, the participants also provided

information about the ideal qualities that ICA needs

to have to break the boundary effectively. All of the

six participants said that in order to act as an effective

internal agent of change and capable of

breaking/overcoming boundaries, the internal change

agent needs to have resilient character/quality, as

shown below:

Excerpt 23

"Yes, being persistant against pressure, against

objections, like that. Don’t easily to give up. The point

is, you have to be tough and to be strong. Don't give

up easily. If you get a negative response, don't give

up"

(P2, female)

This resilience characteristic is often needed

because when managing and encouraging change,

boundaries, resistance, and negative responses from

change targets are found. With this resilience, internal

change agents will not give up easily and are even

more motivated to break boundaries, implement, and

encourage change. The resilience character required

by this ICA confirms the findings of Randall et al.

(2019) and Burke (2011), who state the same thing.

Another quality required by an internal change

agent effective in overcoming boundaries and

implementing change was mentioned by participant

5, namely having interpersonal skills to break

boundaries and communicate the steps for

implementing change towards change targets

effectively.

Excerpt 24

“Okay, The interpersonal skill must be good. Because

change is certain to happen and mostly when we talk

at corporate it is certain that people are definitely

rigid. Whether you have already worked there for a

long time, but once you become change agent, people

will see you differently, right? ‘What's the change?

We’re already comfortable. I'm fine here, my

performance doesn't bother me. What changes

again?’ So if there is a change, that must be it. So

interpersonal must be good to overcome those

rigidity"

(P4, female)

ICA also needs to have interpersonal skills

because in managing change, there must be

boundaries in the form of differences and social

dynamics between several parties so that the

interpersonal skills possessed by ICA are needed to

span these differences in social identities.

4 CONCLUSIONS

As the conclusion, this study highlighted four types

of boundaries: political, structural, interpersonal, and

knowledge, experienced by ICA in managing change

in their organizations, as also mentioned by Wright

(2009) in the classification of boundary aspects.

Although the classification of the boundaries is the

same as the previous studies, the nature of the

boundaries is unique. For example, the diversity of

demographic background becomes an interpersonal

boundary in the Indonesian context. Furthermore,

seniority was salient as the political boundary.

In terms of boundary spanning, this study

indicated three effective strategies implemented by

ICA to manage organizational change: 1)

organizational support, 2) invite participation, and 3)

communication. To perform the strategies

effectively, the internal change agent needs to be

highly resilient and good at interpersonal skills.

The findings contributed to literature related to the

nature of boundaries experienced by internal change

agents, particularly in the specific context of

Indonesia as a collectivistic society. The findings also

had significant practical implications on identifying

internal change agents' essential competencies to

manage change in organizations effectively.

REFERENCES

Ancona, D.G. (1990). Outward Bound: Strategies for team

survival in an organization, Academy of Management

Journal 33 (2): 334–336.

Ancona, D.G. and Caldwell, D.F. (1992). Bridging the

Boundary: External activity and performance in

organizational teams, Administrative Science Quarterly

37 (4): 634–665.

Babbie, E. R. (2014). The basics of social research. Sixth

edition. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

Balogun, J., Gleadle, P., Hope Hailey, V., Willmott, H.

(2005). British Journal of Management, Vol 16, 261-

278.

Bartunek, J.M., Rousseau, D.W., Rudolph, J.W., DePalma,

J.A. (2006). On the Receiving End: Sensemaking,

Emotion, and Assessments of an Organizational

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

400

Change Initiated by Others. Journal of Applied

Behavioral Science, Vol. 42 No. 2, June 2006 182-206.

Berg, B.L. (2017). Research method for the social sciences.

Long Beach: Pearson.

Boyatzis, Richard. (1998). Transforming Qualitative

Information: Thematic Analysis and Code

Development.

Burke, W. (2011). A Perspective on the Field of

Organization Development and Change: The Zeigarnik

Effect. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 47

(2), 143–167

Coffman, K, Lutes, K. (2007). Change Management:

Getting User Buy-In. USA: Management of Change.

Cummings, T. G., & Worley, C. G. (2009). Organization

development and change 9th edition. Mason, Ohio:

Thomson/South-Western

Davidson, Jeff. 2005. Change Management. Jakarta:

Prenada Media.

Edwards, R., Holland, J. (2013). What is Qualitative

Interviewing?: The 'What is?' Research Methods Series.

Edinburgh: A&C Black

Ernst, C., Yip, J. (2009). Boundary Spanning Leadership:

Tactics to Bridge Social Identify Group in

Organizations, In TL Pittinsky (Ed), Crossing The

Divide: Intergroup Leadership in A World of

Difference (pp.88-89), Boston: Harvard Business

School Press.

Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013).

Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes

on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research

Methods, 16(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/

1094428112452151

Giles, H., Ogay, T. (2007) Communication:

Accommodation Theory. In B.B. Whaley & W. Samter

(Eds.), Explaining Communication: Contemporary

Theories and Exemplars (pp 293-310). NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum

Greenberg, J., Baron, R.A. (2003). Behavior in

Organizations Understanding and Managing the

Human Side of Work. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

International.

Hartley, J., Benington, J. and Binns, P. (1997). Researching

the Roles of Internal-change Agents in the Management

of Organizational Change. British Journal of

Management, 8, 61– 73.

Heller, R. (2002). Essential Managers: Managing Change

(cetakan pertama). Jakarta: Penerbit Dian Rakyat.

Hermann, M., Pentek, T., Otto, B. (2015). Design

Principles for Industrie 4.0 Scenarios: A Literature

Review. 10.13140/RG.2.2.29269.22248.

Higgs, M. and Rowland, D. (2011). What Does It Take to

Implement Change Successfully? A Study of the

Behaviors of Successful Change Leaders. Journal of

Applied Behavioral Science 47(3) 309–335.

Hofstede, G. (1981), Motivation, Leadership, and

Organization: Do American Theories Apply Abroad?

Organizational Dynamics, Summer, 42-63.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010).

Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind.

Revised and Expanded 3rd Edition. New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Jesiek, B., Trellinger, N., Mazzurco, A. (2016). Becoming

Boundary Spanning Engineers: Research Methods and

Preliminary Findings. 10.18260/p.26370.

Kotter, J.P. (1996). Leading Change. Boston: Harvard

Business Press.

Li, Jo-Yun, Sun, R., Tao, W., Lee, Y. (2021). Employee

coping with organizational change in the face of a

pandemic: The role of transparent internal

communication. Public Relations Review, Volume 47,

Issue 1, 2021, 101984,ISSN 0363-8111.

Lune, H., Berg, B.L. (2017). Qualitative Research Methods

for the Social Sciences, 9th edition, ISBN 978-0-134-

20213-6. Edinburgh: Pearson Education

Lunenburg, F.C. (2010) Managing Change: The Role of the

Change Agent. International Journal of Management

Business, and Administration, 13, 1-6.

Maitlis, S. (2005). The Social Processes of Organizational

Sensemaking. The Academy of Management Journal,

48, (1), 21-49

Maurer, R. (2010). Beyond the Wall of Resistance: Why

70% of All Changes Still Fail-- And What You Can Do

About It. Austin Texas: Bard Press

Marrone, J.A., Tesluk, P.E. and Carson, J.B. (2007). A

Multi-level Investigation of Antecedents and

Consequences of Team Member Boundary Spanning

Behavior, Academy of Management Journal 50 (6):

1423–1439.

Matous, P.; Wang, P. (2019). External exposure, boundary-

spanning, and opinion leadership in remote

communities: A network experiment. Social Networks.

56: 10–22. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2018.08.002

Meyerson, J.W., Sculley, M.A. (1995). Tempered

Radicalism and the Politics of Ambivalence and

Change. Organization Science, Vol 6 (5), 585-600.

Muhammad, R. (2005). Pengaruh Struktur Organisasi

Terhadap Komunikasi Dalam Tim Audit. JAAI Volume

9 No. 2, Desember 2005: 127 – 142

Mulyaningsih. (2020). Rekontruksi Karakteristik Budaya

Organisasi Di Indonesia Dalam Meningkatkan

Kompetensi Sumber Daya Manusia (Persiapan

Menghadapi Asia Future Shock 2020). Jurnal Ilmiah

P2M STKIP Siliwangi 7 (1), 74-81

Neergaard, M.A., Olesen, F., Andersen, R.S. (2009)

Qualitative description – the poor cousin of health

research?. BMC Med Res Methodol 9, 52.

https://doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2288-9-52

Nugroho, R. (2013). Change Management untuk Birokrasi:

Strategi Revitalisasi Birokrasi. Jakarta: Elex Media

Komputindo

Orlikowski, W.J. (2002). Knowing in Practice: Enacting a

Collective Capability in Distributed Organizing.

Organization Science, INFORMS, vol. 13(3), pages

249-273, June.

Palmer, I., Dunford, R., & Akin, G. (2017). Managing

organizational change: A multiple perspectives

approach. 3ed ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Palus, C., & Mcguire, J., Ernst, C. (2011). Developing

Interdependent Leadership. SAGE Publications

Internal Change Agents’ Strategies to Deal with Boundary in Organizations in Indonesia

401

Patton M.Q. (2014). Qualitative research and evaluation

methods. 3rd Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publications

Pusat Data Statistik Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan (2016).

Analisis Kearifan Lokal Ditinjau dari Keragaman

Budaya. Jakarta: Kementrian Pendidikan dan

Kebudayaan Republik Indonesia

Randall, J. A., Burnes, B. Dawson, P. (2019). Internal

change agents: boundary spanned and the implications

for change agency. British Academy of Management.

September 2019.

Randall, J. A., Burnes, B. Sim, Allan J. (2019)

Management consultancy: The role of the change agent.

London: Red Bull Press.

Robbins, Stephen P & Judge, Timothy A. (2017).

Organizational Behavior Edition 17. New Jersey:

Pearson Education

Sagiv, L, Schwartz, S. (2007). Cultural Values in

Organisations: Insights for Europe. European Journal of

International Management. 1. 176-190.

10.1504/EJIM.2007.014692.

Sagiv, L., Schwartz, S., Arieli, S. (2011). Personal values,

national culture and organizations: Insights applying

the Schwartz value framework.. 10.4135/978148330

7961.n29.

Sandelowski, M. (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative

description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23, 334–

340.

Sandelowski, M. (2010). What’s in a name? Qualitative

description revisited. Research in Nursing & Health, 33,

77–84.

Sari, I.P., Wulandari, R.D. (2015). Penilaian Koordinasi

Antarunit Kerja di Rumah Sakit Berdasarkan High

Performance Work Practices. Jurnal Administrasi

Kesehatan Indonesia Volume 3 Nomor 2 Juli-

Desember 2015

Schotter, A. P. J., Mudambi, R., Doz, Y.L. and Gaur, A.

(2017) Boundary spanning in global organizations.

Journal of Management Studies, 54 (4), 403 – 421.

Schwartz, H. and Davis, S.M. (1981) Matching Corporate

Culture and Business Strategy. Organizational

Dynamics, 10, 30-48. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0090-

2616(81)90010-3

Senge, P. (1999). The Dance of Change. Toronto, Ontario:

Doubleday Press

Senior, B. (2002). Organisational Change. Harlow:

Financial Times Prentice Hall.

Sihombing, S.O., Pongtuluran, F.D. (2012).

Pengidentifikasian Dimensi-Dimensi Budaya

Indonesia: Pengembangan Skala dan Validasi. Jurnal

Penelitian Fakultas Ekonomi dan Bisnis: Business

School Universitas Pelita Harapan.

Silalahi, E.E. (2017). Budaya Organisasi Perusahaan

Asuransi Jiwa Di Indonesia. Jurnal Ilmiah Manajemen,

Volume VII, No. 1, Feb 2017

Smither, R. D., Houston, J. M., & McIntire, S. A. (2016).

Organization development: Strategies for changing

environments. New York: Harper Collins College

Publishers.

Sturdy, A., Wright, C. and Wylie, N. (2016) Managers as

consultants: The hybridity and tensions of neo-

bureaucratic management. Organization, 23 (2), 184–

205.

Weiner, B. J. (2009). A theory of organizational readiness

for change. Implementation Science : IS,4, 67.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-67

Wibowo. 2012. Pengelolaan Perubahan. Jakarta: Rajawali

Press.

Winardi. 2011. Kepemimpinan dalam Manajemen. Jakarta:

Rineka Cipta.

Worldailmi, E., Hartono, B. (2017). Kajian Teoritis Peran

Manajer Menengah di Proyek sebagai Boundary

Spanner. Seminar Nasional Teknik Industri Universitas

Gadjah Mada 2017. Departemen Teknik Mesin dan

Industri FT UGM. ISBN 978- 602-73461-6-1

Worldailmi, E., Hartono, B. (2018). Boundary Spanning,

Kinerja Middle Manager Proyek dan Kinerja Proyek

Konstruksi. Universitas Gadjah Mada. Diakses pada

tanggal 15 November 2020 dari

http://etd.repository.ugm.ac.id/

Wright, C. (2009). Inside Out? Organizational Membership,

Ambiguity and the Ambivalent Identity of the Internal

Consultant. British Journal of Management, 20, 309–

322.

Yin, R. K. (2016). Qualitative research from start to finish.

New York: Guilford Press.

Yustiarti, F., Hasan, A., Hardi (2016). Pengaruh Konflik

Peran, Ketidakjelasan Peran, dan Kelebihan Peran

terhadap Kinerja Auditor dengan Kecerdasan

Emosional sebagai Pemoderasi. Jurnal Akuntansi, Vol.

5, No. 1, Oktober 2016: 12 – 28

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

402