Systematic Literature Review on Mindset and the Benefits in Living

New Normal Life

Ira Adelina

a

, Vida Handayani

b

and Maria Yuni Megarini

c

Faculty of Psychology, Maranatha Christian University, Surya Sumantri 65, Bandung, Indonesia

Keywords: Stress, Mindset, COVID-19, Pandemic, New Normal.

Abstract: Pandemics are associated with lots of psychosocial stressors, such of separation of family and friends,

shortages of food and medicine, wage loss, social isolation, financial hardship, death, trauma, and so on. The

psychological effects of the pandemic will likely be more pronounced, more widespread, and longer lasting

than the purely somatic effects of infection. This pandemic period causes intense stress for individuals.

Mindset, as a belief whether ability and intelligence are fixed or changeable traits, plays a critical role in how

we cope in life’s challenges. This research uses descriptive method, in a form of systematic literature review

from more than 50 articles, taken from psychological and medical journals in the last 35 years. The journals

related to the pandemic situation from medical and psychological perspectives, along with its interventions.

Based on this review, we conclude that mindset plays an important role in individual’s appraisals and

responses to stressors. Responses given by individual’s can be adaptive responses that lead to effective coping,

or maladaptive and lead to coping that is ineffective and even malfunctioning and disrupted health during

pandemic.

1 INTRODUCTION

Pandemics are large-scale epidemics afflicting

millions of people across multiple countries,

sometimes spreading throughout the globe (WHO,

2010b). According to Killbourne (1977) in Taylor

(2019), for a virus or bacterium to cause a pandemic

it must be an organism for which most people do not

have pre-existing immunity, transmitting easily from

person to person, and causing severe illness. Diseases

causing pandemics are part of a group of conditions

known as emerging infectious diseases, which

include newly identified pathogens as well as re-

emerging ones.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which

reported in an outbreak in 2019 in Wuhan, Hubei

province, China, is caused by the SARS-CoV-2

virus. Coronavirus (CoV) is among the main

pathogenic organisms that affect the respiratory

system in humans. In December 2019, the prevalence

of the virus increased at an epidemic rate since its first

occurrence in Wuhan. On 11 February 2020, the

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3720-8211

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3544-9559

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6563-6251

novel virus began to cause pneumonia, and was

named as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by

the World Health Organisation (WHO). Currently,

COVID-19 cases have been recorded globally (Rauf,

Et. Al., 2020). According to JHU CSSE Covid-19

data on 23 April 2021, reports indicated that

140,849,925 individuals were infected with the

disease of whom 3,013,217 died (Dong, Du, &

Gardner, 2020) .

Pandemics are "frequently marked by uncertainty,

confusion and a sense of urgency" (WHO, 2005).

Prior to, or in the early stages of a pandemic, there is

widespread uncertainty about the odds and

seriousness of becoming infected, along with

uncertainty, and possible misinformation, about the

best methods of prevention and management.

Uncertainty may persist well into the pandemic,

especially concerning the question of whether a

pandemic is truly over. Pandemics can come in

waves. Waves of infection are caused, in part, by

fluctuations in patterns of human aggregation, such as

seasonal movements of people away from, and then

458

Adelina, I., Handayani, V. and Megarini, M.

Systematic Literature Review on Mindset and the Benefits in Living New Normal Life.

DOI: 10.5220/0010754300003112

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences (ICE-HUMS 2021), pages 458-469

ISBN: 978-989-758-604-0

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

into contact with, one another (Taylor, 2019)

Pandemics are related with a score of other

psychosocial stressors, counting wellbeing dangers to

oneself and others, extreme disturbances of schedule,

partition from family and friends, deficiencies of

nourishment and medication, loss, social isolation

because of quarantine or social distancing programs

and school closure, and individual budgetary

challenge. The personal financial impact of a

pandemic can be as severe and stressful as the

infection itself, especially for people who are already

experiencing financial difficulties (Taylor, 2019).

People differ in how they react to psychosocial

stressors such as the threat of, or an actual occurrence

of, a pandemic. Reactions can be diverse, ranging

from fear to indifference to fatalism. Some people

underestimate the risks, so they are less engaged in

recommended health behaviors such as vaccination,

hygiene practices, and social distancing. At the other

hand, many people react with intense anxiety or fear.

Actually, a moderate level of fear or anxiety can

motivate people to cope with health threats, but

severe distress can be debilitating (Taylor, 2019).

People develop beliefs that organize their world

and give meaning to their experiences. These beliefs

are called "meaning systems", and different people

will create different meaning systems. We have belief

systems that give structure to our world and meaning

to our experiences. People's beliefs about themselves

can create different psychological world, leading

them to think, feel, and act differently in identical

situations. Meaning systems are important in shaping

our thinking. The meaning systems that people

adopted were as important or even more important in

shaping their thinking (Dweck, 2000). A mindset is

defined as a mental frame or lens that selectively

organizes and encodes information, thereby orienting

an individual toward a unique way of understanding

an experience and guiding one toward corresponding

actions and responses (Crum, Salovey, & Achor,

2013).

Many studies examine how a person's mindset

affects the way he interprets and solves problems.

When facing challenging problems, people who

believe that effort drives intelligence tend to do better

than people who believe that intelligence is a fixed

quality that they cannot change. Individual with a

fixed mindset avoids challenges, gives up

effortlessly, sees effort as vain or more regrettable,

overlook valuable negative input, and feels

debilitated by the others succeeds. In the meantime,

people with a growth mindset embraces challenge,

persists despite setbacks, sees effort important to gain

mastery, learns from mistakes and criticisms, and

finds lessons and motivation in others success. People

with a growth mindset believe that they can develop

their abilities through hard work, persistence, and

dedication (Dweck, 2006; Elliot & Dweck, 2005;

Weiner, 2005). Research also suggests that good

problem solvers are qualitatively different from poor

problem solvers (National Research Council, 2004;

Schoenfeld, 2007). Good problem solvers are flexible

and resourceful. They have many ways to think about

problems, have alternative approaches if they get

stuck, ways of making progress when they hit

roadblocks, of being efficient with (and making use

of) what they know.

Other studies examine how the role of mindset in

dealing with stressful situations. Stress mindset is

related with psychological stress responses, through

coping strategies (Horiuchi, Tsuda, Aoki, Yoneda, &

Sawaguchi, 2018). Crum et al. (2013) found that

individuals with a stronger stress-is-enhancing

mindset utilized approach and active coping more

frequently and avoidant or withdrawal coping less

frequently. They showed that coping and stress

mindset were independently related with

psychological stress responses. Researches related to

the pandemic situation also turned out to provide

many findings on how mindset changes can help

overcome the pandemic situation. Therefore, the

purpose of this study is to integrate all of these

findings and explain them systematically and

thoroughly.

2 METHODS AND MATERIALS

This research based on descriptive methods in form

of systematic literature review. Articles related to this

literature review were searched through a computer-

based article data search program, the Google

Scholar, Scopus, and Proquest program. The

keywords are mindset, stress, and pandemic. All the

article findings were considered according to the

criteria as a requirement. The inclusion criteria for an

article to meet the requirements for analysis is that the

research contains a pandemic condition which

explains the mindset and stress variables. The

primary study was conducted using a survey that

examined the mindset. Based on the inclusion criteria

that have been set, it was found 50 research articles

started from 1994 and the following data were

processed into 22 studies. The research articles found

were taken from the Journal of Public Health

Management and Practice, Behavioral and Cognitive

Systematic Literature Review on Mindset and the Benefits in Living New Normal Life

459

Psychotherapy, Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, Journal of Psychiatry, Psychological

Review, International Journal of Health Management

and Information, American Journal of Public Health,

Stress and Health Journal, Journal of Abnormal

Psychology, Journal of Health Communication,

Journal of Behavioral Medicine, Psychiatry

Research, Clinical Psychology Review, and Journal

of Health Psychology. The results of the research

findings are then arranged into a table, analysed

through logical thinking, and then a conclusion is

drawn.

3 RESULT AND DISCUSSION

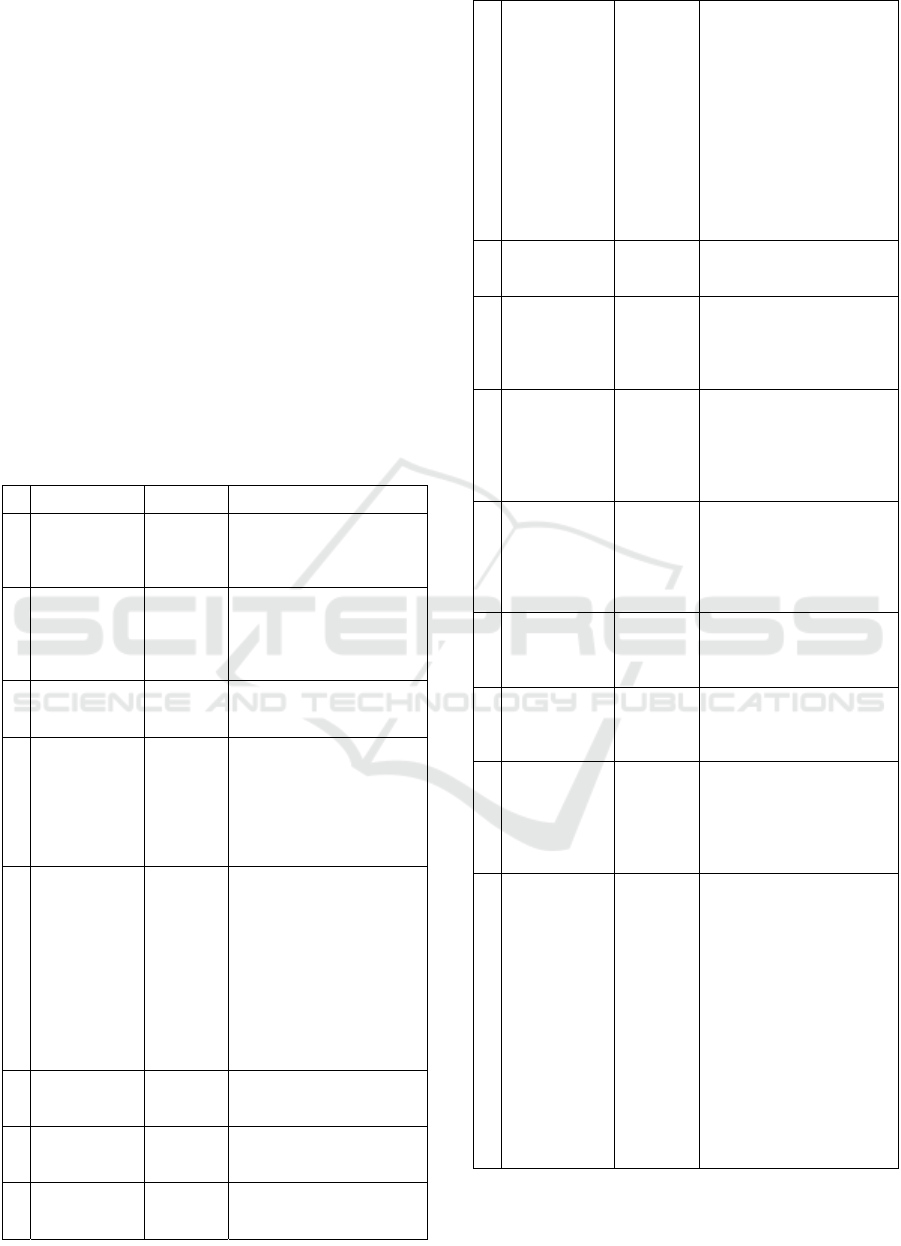

Research results can be found in table 1.

Table 1: Systematic literature review results.

No Researcher Keywords Results

1

L

oeb & Dweck

(

1994)

Stress,

mindset

People with growth mindset

tend to take a more direct

and active problem-solving

approach.

2

D

weck (2000) Stress,

mindset

Growth mindset may help us

to construct the lives we

want and to maintain the

flexibility to reconstruct

them when things go wrong.

3

T

aylor & Asmu

n

dson(2004)

Stress,

mindset,

health

Grossly inaccurate beliefs

can contribute to excessive

health anxiety.

4

T

aylor & Asmu

n

dson(2004);

W

heaton,

A

bramowitz,

B

erman,

F

abricant, &

O

latunji (2012)

Stess,

mindset

People with excessive health

anxiety tend to misinterpret

harmless bodily sensations.

5 WHO (2008,

2012); World

Health

organization

Writing Group

(2006)

Stress,

mindset,

pandemic

Psychological factors are

also relevant for under-

standing and addressing the

socially disruptive behavioral

patterns that can arise as a

result of widespread, serious

infection. Contemporary

methods for managing

pandemics are largely

behavioral or educational

interventions.

6

L

evi, Segal, St.

L

aurent, &

L

ieberman(2010)

Mindset,

pandemic

Attitudes about vaccination

are influenced by one's

b

eliefs about the vaccination.

7 Crum et al.,

(2013)

Stress,

mindset,

health

Stress mindset alters health-

related outcomes.

8 Dweck, (2017) Stress,

mindset

-

Several personality traits

have been linked to the

vulnerability to experience

negative emotions in

response to stressors.

-

Those with the growth

mindset, believe they can

develop their selves, open

to accurate information

about their current abilities,

oriented toward learning.

-

Cognitive therapy helps

people make more realistic

and optimistic judgments

into the framework of

growth.

9 Leventhal,

Phillips, &

Burns, (2016)

Stress,

mindset,

health

People can hold erroneous

beliefs about what is an

effective treatment

10 Taylor, (2017) Mindset,

pandemic

People with persistent

pandemic related PTSD would

likely benefit from empirically

supported treatments such as

trauma-focused CBT.

11 Gautreau et al

(2015); Hagger,

Koch,

Chatzisarantis,

& Orbell,

(2017)

Mindset,

stress

Cognitive-behavioral models

propose that excessive

anxiety about one's health is

triggered by the

misinterpretation of health-

related stimuli.

12 Cooper,Gregory,

Walker, Lambe

& Salkovskis,

(2017); Steven

Taylor & Asmu-

ndson, (2004)

Mindset,

stress

Cognitive-behavioral models

suggest that excessive health

anxiety can be addressed by

targeting dysfunctional

beliefs and maladaptive

b

ehaviors.

13 Taylor &

Asmundson(20

04); Tyrer &

Tyrer (2018)

Mindset,

stress

CBT, as conducted by a

therapist, is currently the first-

line treatment for excessive

health anxiety.

14 Tang, Bie,

Park, & Zhi,

(2018)

Mindset,

stress,

pandemic

Social media can fuel or quell

fears, and they can influence

the spreading of disease by

influencing people's behavior.

15 Keech,

Hagger, &

Hamilton

(2021)

Stress,

mindset

A stress-is enhancing mindset

can be induced through

intervention and have been

shown to be effective in

mitigating negative outcomes

to highly stressful events.

16 Taylor (2019) Mindset,

stress,

pandemic

- Cognitive and behavioral

factors play a role in

shaping the severity of

health anxiety:

Misinterpreta-tions of

health-related stimuli,

maladaptive or distorted

beliefs, memory and

attention processes, and

maladaptive behaviors

- Beliefs and fears about

diseases, just like diseases

themselves, spread through

social networks. Beliefs

and rumors also influence

the spread of infection.

Mindset is grounded on implicit theories, which

are knowledge structures about the malleability of an

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

460

attribute such as intelligence and personality that

organize the way people ascribe meaning to events.

Research on implicit theories distinguishes between

two main beliefs or mindsets: an incremental or

growth mindset and an entity or fixed mindset

(Dweck, 2000; Dweck & Leggett, 1988) Those with

growth mindsets believe that human attributes are

malleable and therefore can be cultivated through

hard work, good strategies, and support from others.

They have a dynamic self and a dynamic world,

capable of growth. These beliefs help us move

forward with determination, encourage us to look for

ways to remedy our deficiencies and to solve our

problems. In contrast, other beliefs portray a more

static self and world with inherent, fixed qualities.

Those with fixed mindsets believe that human

attributes are fixed and therefore cannot be

developed, regardless of the effort expended or

strategy employed. These beliefs may have some

advantages, because they portray a simpler world that

is potentially easy to know, and there may be a great

deal of security in that. Entity beliefs can lead us to

make more rigid judgements, sometimes blinding

ourselves from our capabilities, and limiting the path

we pursue. Research finds that people can hold

different mindsets in different domains and the effects

are typically stronger for domain-specific

assessments (Scott & Ghinea, 2014). These beliefs

are part of people’s motivational systems. People’s

mindset has impact on their judgment, evaluations,

health, and behavior. Using one mindset or another

can significantly influence psychological, behavioral,

and physiological results in life and health domains

(Crum et al., 2013).

People tend to feel positive or negative emotions

because of the meaning they give to something that

has happened. Seligman and his colleagues set about

assessing individual differences in the kinds of causal

explanations that people tend to make for negative

events in their lives. They called this “explanatory

styles”. Some people tend to focus on more

pessimistic explanations for negative events, blaming

more global and stable factors, while other tend to

focus on more optimistic explanations, blaming more

specific and temporary ones (Dweck, 2000).

Cognitive-oriented theories of mental health and

psychotherapy start with the assumption that people’s

erroneous beliefs can get them into trouble. There are

series of beliefs that characterize individuals who are

vulnerable to emotional distress. Pessimistic

explanatory styles are also cognitive models of

vulnerability. While not denying biological

contributions to emotional disorders, research

therapies in this field show that many people with

depression or anxiety disorders are victims of their

maladaptive beliefs and alteration in these beliefs will

help them greatly (Dweck, 2000).

An entity theory framework can lead people to

overgeneralize from one experience, to categorize

themselves in unflattering ways, to set self-worth

contingencies, to exaggerate their failures relative to

their successes, to lose faith in their ability to perform

even simple actions, to underestimate the efficacy of

effort – all things that have been implicated in

depression. Pessimistic explanatory styles went on

the power of a helpless, and the power of an

optimistic explanatory styles to predict mental and

physical health (Dweck, 2000). Vulnerable people

don’t just think and react in different ways from less

vulnerable people. They also value different goals.

Compared with the less vulnerable people, they are

more concerned with validating themselves and less

concerned with growth and self-development

(Dweck, 2000).

Individual appraisal of the causes of stress will

determine their response. Research conducted by

Lazarus and Folkman, highlighted the importance of

cognitive appraisal in determining responses to stress.

The study proposes that individuals initially assess

the extent to which the situation is considered

demanding (primary appraisal) and then assess

whether they have sufficient resources or not to cope

with the situation (secondary appraisal). Recently,

researchers describe the stages of how individuals

assess a situation and highlight that the response to

stress is determined by the balance of perceived

resources (knowledge and skills), perceived demands

(danger and uncertainty), and the identification of the

physiological support for the challenges and threats

of these individual assessments (Crum, Akinola,

Martin, & Fath, 2017).

Stress mindset refers to the properties and desires

attributed to stress; coping refers to the process of

appraising threat and organizing cognitive and

behavioral resources to encounter stress when it does

occur. In other words, whereas stress mindset may

inform the coping strategy that one adapts, as the

mental and motivational situation in which coping

activity are chosen and occupied, it isn’t by itself a

coping strategy (Crum et al., 2013).

Mindsets plays an important role in stress

appraisals which will then determine individual’s

reactions to stressors are adaptive and point to

effective coping, or maladaptive and end in

ineffective coping and compromised health and

wellbeing. The main point of these concept is that

people who appraise stress as challenging and have

beliefs that stress can be enhancing and encouraging

Systematic Literature Review on Mindset and the Benefits in Living New Normal Life

461

interest of valued goals, cope more effectively and

show better outcomes. As opposed, people who

appraise stress as threatening, and have beliefs that

stress can be debilitating suboptimal in goal pursuit

(Hagger et al., 2017).

It is proposed that, when people feature a stress-

is-debilitating mindset, their arousal levels are likely

to be hypo- or hyperactivated. Arousal levels may be

hypoactive under stress as an impact of avoidance or

denial of the stress or the use of counteractive coping

mechanisms such as medications or substance use.

Alternatively, arousal levels may be hyperactivated

directly as a result of the additional stress that comes

from having a stress-is-debilitating mindset or

indirectly through counter-effective reactions of

emotional suppression, experiential avoidance, or

ruminative thought. Contrarily, people with stress is

enhancing mindset, more likely to attain an optimal

level of arousal when under stress, they have enough

arousal needed to fulfil goals and demands but not

exaggerated to debilitate physiological health at last.

Researches also show that changes in mindsets can

affect health through indirect changes in behavior and

physiology (Crum et al., 2013).

A stress-is-enhancing mindset is parallel with an

incremental perspective, such that individuals have a

flexible perspective on stress and have beliefs that

stress is an opportunity for growth with the potential

to facilitate performance and functioning (Crum et al.,

2013). In contrast, a stress-is debilitating mindset is

more in line with an entity perspective such that

people have a view that stress is harmful. A

developing research has shown that people with

stress-is-enhancing mindset experienced reduced

physiological stress responses, greater positive affect

and cognitive flexibility, better self-rated health,

higher life satisfaction, and better academic and work

performance (Crum et al., 2013). Furthermore,

research in various situation has shown that a stress-

is enhancing mindset can be induced through

intervention and shown effective result in relieving

highly stressful events (Crum et al., 2017, 2013;

Keech et al., 2021).

Researchers stated that stress might be beneficial,

at least up to a certain point. But once stress hits a

critical point or allostatic load, it becomes debilitating

(distress), pictured as an inverted-U-shaped curve

represent the relationship between arousal and

performance. The assumption that an objective level

of stress predicts physical and psychological results

largely has been obscured by the idea that responses

to stress are driven by how people manage or

anticipate the negative impacts of stress; in effect,

how—and how well—they adapt (Crum et al., 2013).

These beliefs can be influenced or changed by an

explicit message, or indirectly by other people’s

feedback (Dweck, 2006).

Coping preferences may grow out of meaning

systems. Some beliefs and goals may help us to

construct the lives we want and to maintain the

flexibility to reconstruct them when things go wrong.

Although most theories view coping as a process and

resist thinking in term of traits and rigid coping styles,

there has been identified more adaptive coping

strategies that tend to be more mastery-oriented,

active, and effective. They must adopt new goals, and

they must learn new strategies for attaining their

goals. Their successful adjustment depends on how

well this is done (Dweck, 2000).

The hypothetical supporting the suggestion that

stress mindset changes health and performance is that

different stress mindsets will be associated with

distinctive processes of motivational and

physiological. Specifically, it is said that stress

mindset has a significant impact on the manner in

which stress is behaviorally approached as well as the

manner in which stress is psychologically

experienced which these short-term impacts on

physiology and motivation have long-term impacts

on health and performance outcomes (Crum et al.,

2013). People with growth mindset tend to take more

direct problem-solving approach, while those with

fixed mindset tend to lost in negative feelings or turn

away from the problem and try to make themselves

feel better. Studies by Loeb & Dweck (1994) show a

similar thing. When confronted with scenarios

portraying them as victims, again, those with growth

mindset reported that they would take a more active

problem-solving stance, while those with fixed

mindset showed more passive acceptance but

admitted they would harbor long-term hatred and

wishes of revenge.

More particularly, in case people has a stress-is-

debilitating mindset, their primary motivation is to

avoid or manage the stress, preventing it from

becoming debilitating outcomes. On the other hand,

when one has a stress-is-enhancing mindset, their

primary motivation is to accept and utilize stress

toward achieving enhanced outcomes. As such, in the

event one has a stress is-debilitating mindset, one will

be more likely to engage in actions and coping

behaviors that act to avoid or manage the stress itself

(in an effort to prevent debilitating outcomes from

happening). On the other hand, if people have a

stress-is-enhancing mindset, they will more likely

engage in actions that help meet the demand, value,

or goal underlying the stressful situation (Crum et al.,

2013).

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

462

Psychological factors play an important role in the

way in which people cope with the threat of pandemic

infection and its sequelae. Although many people

cope well under threat, many other people experience

high levels of distress or a worsening of pre-existing

psychological problems, such as anxiety disorders

and other clinical conditions. Psychological factors

are further important for understanding and managing

broader societal problems associated with pandemics,

such as factors involved in the spreading of excessive

fear. People may fear for their health, safety, family,

finances, or jobs. Psychological factors are also

important for understanding and managing the

potentially disruptive or maladaptive defensive

reactions, such as increases in stigmatization and

xenophobia that occur when people are threatened

with infection (Taylor, 2019). If examined deeply,

people behaviors during pandemic can be explained

on the mindset perspective.

Several personality traits have been linked to the

vulnerability to experience negative emotions in

response to stressors. These traits are interrelated and

transdiagnostic in that they are associated with a

range of emotional problems (Kring & Sloan, 2010;

Norton & Paulus, 2017). Every type describes

people’s behavior, but more importantly, is the

psychological reasons for people’s behavior – about

the beliefs and goals people bring to a situation that

caused them to act in certain ways (Dweck, 2000).

Negative emotionality, also known as neuroticism, is

the general tendency to become easily distressed by

aversive stimuli. People who scored high on this trait

tend to often experience aversive emotions such as

anxiety, irritability, and depression in response to

stressors (Costa & McCrae, 1987). Therefore, it is not

surprising that the severity of a person's negative

emotionality predicts their likelihood of becoming

distressed by the threat of infection. They tend to

overestimate of threat. People who score high on

overestimation threat tend to overestimate the cost

("badness") and probability (likelihood) of aversive

events, and see themselves as being especially

vulnerable to threats (Frost & Steketee, 2020). The

impact is they are likely to become highly worried

and anxious because their estimates of being harmed

tend to be inflated compared to the estimates of

people scoring lower on these traits. The intolerance

of uncertainty is another facet or sub-trait of trait

anxiety that can contribute to the tendency to

experience anxiety and fear (McEvoy & Mahoney,

2013). They have a strong desire for predictability.

When faced with important uncertainties, these

people might feel paralyzed with indecision (Birrell,

Meares, Wilkinson, & Freeston, 2011). During the

pandemics, the intolerance of uncertainty is likely to

be a particularly important contributor to pandemic-

related anxiety and distress. During times of

pandemics, people need to be able to tolerate or

accept a certain degree of uncertainty. People who are

unable or unwilling to accept uncertainty are likely to

experience considerable distress. People with a high

degree of intolerance of uncertainty tend to become

highly anxious about the threat of infectious disease,

especially if they perceive themselves as having

limited control over the threat (Taha, Matheson,

Cronin, & Anisman, 2014)

Unlike the above-mentioned traits, which are

associated with negative beliefs or expectations, the

unrealistic optimism bias is associated with persistent

and unrealistically positive beliefs about one's future

(Taylor & Brown, 1988). Optimism-defined as the

hope that something good is going to happen (Carver,

Scheier, & Segerstrom, 2010) can be a state variable

or an enduring personality trait. Optimism trait, which

is our focus here, is negatively correlated with

negative emotionality, although the correlation is far

from perfect (Kam & Meyer, 2012). Regardless of

these theoretical debates, people scoring low on traits

such as negative emotionality generally tend toward

optimism. Many people, although the precise

prevalence is unknown, have an unrealistic optimism

bias (Makridakis & Moleskis, 2015). This is the

strong tendency to believe that positive events are

more likely to happen to themselves than to others,

and that negative events are more likely to happen to

other people than themselves. Such people tend to

undervalue dangers such as diseases and other

hardships, whose existence they accept but cannot

believe will happen to themselves (Makridakis &

Moleskis, 2015). People with strong unrealistic

optimism bias tend to see themselves as impervious

to infection (Ji, Zhang, Usborne, & Guan, 2004; Kim

& Niederdeppe, 2013). In the event of a pandemic,

the unrealistic optimism bias can have deleterious

effects. It may lead people to underestimate their

susceptibility to risk, thereby reducing attention to

risk information and leading them to neglect to do

preventive health behaviors such as seeking

vaccination (Kim & Niederdeppe, 2013). The

unrealistic optimism bias can be resistant to change in

the face of disconfirming information (Sharot, Korn,

& Dolan, 2011). Related to the unrealistic optimism

bias is the sense of invulnerability. That is, the sense

that one is unlikely to be affected by threats such as

serious infectious disease. People with an inflated

sense of invulnerability are (1) less likely to

experience anxiety in response to stressful life events;

(2) more likely to take up smoking or drug use; (3)

Systematic Literature Review on Mindset and the Benefits in Living New Normal Life

463

more likely to drink and drive; and (4) less likely to

intend to seek vaccination, even for pandemics such

as Swine flu (Taylor, 2019). During the next

pandemic, people with strong unrealistic optimism

bias or a strong sense of invulnerability will probably

be less worried than other people and possibly more

likely to spread infection by failing to seek

vaccination and by neglecting to do basic hygiene

behaviors such as hand washing.

Maybe the people with the growth mindset more

likely to have expanded sees of their capacity and try

for things they’re not capable of? In truth, Researches

show that people are terrible at estimating their

abilities. But people with the fixed mindset who

accounted for almost all the inaccuracy. The people

with growth mindset were amazingly accurate

(Dweck, 2017). Those with growth mindset, believe

they can develop their selves, open to accurate

information about their current abilities, even if it’s

unflattering. What’s more, in case they’re situated

toward learning, they require exact information about

their current abilities to learn effectively. However, if

everything is either good news or bad news about

their precious qualities —as it is with fixed mindset

people—distortion almost inevitably enters the

picture. Some outcomes are magnified, others are

ignored, and before they realize it, they become

unrealistic.

Health anxiety refers to the tendency to become

alarmed by illness related stimuli, including but not

limited to, illness related to infectious diseases.

Health anxiety ranges on a continuum from mild to

severe, and can be a state or a trait. The latter is a

relatively enduring tendency. Our focus is on trait

health anxiety. Some people have very low levels of

health anxiety. Their lack of concern about health

risks can be maladaptive (e.g., neglecting to take

necessary health precautions). Excessively low health

concerns can be associated with an unrealistic

optimism bias, as discussed before. People who are

unconcerned about infection tend to neglect to do

recommended hygienic behaviors, such as washing

their hands after using the washroom and tend to be

nonadherent to social distancing (Taylor, 2019).

Excessively high health anxiety is characterized

by undue anxiety or worry about one's health. That is,

a disproportionate concern, given one's objective

level of health. People with excessively high levels of

health anxiety, compared to less anxious people, tend

to become unduly alarmed by all kinds of perceived

health threats, and overestimate the likelihood and

seriousness of becoming ill (Hedman et al., 2016).

Excessive health anxiety is associated with high

levels of functional impairment and high levels of

health care service utilization, even after controlling

for physical comorbidities (Bobevski, Clarke, &

Meadows, 2016; Eilenberg, Frostholm, Schroder,

Jensen, & Fink, 2015). Excessive health anxiety-as

seen in psychiatric disorders such as hypochondriasis,

illness anxiety disorder, and somatic symptom

disorder is common, with an estimated lifetime

prevalence of 6% in the community (Sunderland,

Newby, & Andrews, 2013). People prone to

excessive health anxiety are likely to become

particularly anxious during a threatened or real

epidemic or pandemic. Such people may misinterpret

somatic stress reactions (e.g., sweating, hot flushes,

increased muscle tension) as signs of infection.

Furthermore, they can experience the nocebo effect,

which occurs when negative expectations about

treatment (e.g., a vaccination injection) cause the

patient to experience negative side effects (Taylor,

2019). Traits such as negative emotionality

(neuroticism) may predispose people to experience

the nocebo effect (Data-Franco & Berk, 2013).

Interpretations of health-related stimuli are

influenced by memory processes such as

recollections of past experiences and by longstanding

beliefs (Salkovskis & Warwick, 2001; Taylor &

Asmundson, 2004). Learning experiences (e.g.,

experiences of being hospitalized as a child) can lead

some people to mistakenly believe that their health is

fragile (Taylor & Asmundson, 2004). People with

excessive health anxiety tend to believe that all bodily

sensations or bodily changes are potential signs of

disease (Taylor & Asmundson, 2004) In the case of

influenza, grossly inaccurate beliefs can contribute to

excessive health anxiety. Such beliefs are

unfortunately commonplace. Attentional processes

are important cognitive factors in shaping the

intensity of health anxiety (Norris & Marcus, 2014).

People with excessive health anxiety tend to be

hypervigilant to bodily changes and sensations; that

is, they pay a lot of attention to their bodies and

therefore are likely to notice benign bodily

perturbations. This selective attention increases the

odds of noticing bodily changes or sensations. The

fear of infection led people to persistently focus on

their bodies, leading many people to misinterpret

benign bodily changes or sensations. Selective

attention to bodily states is influenced not only by

internal factors (i.e., sensations, beliefs,

expectations), but also by external stimuli (Taylor,

2019)

People's interpretations influence whether or not

they seek treatment, and whether they seek

appropriate treatment. People can hold erroneous

beliefs about what is an effective treatment Some

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

464

people believe that they only need symptomatic relief

(e.g., cough suppressant medications), which may be

insufficient if the underlying disease needs to be

treated (Leventhal et al., 2016). People's appraisals of

risk are often inaccurate. Indeed, there is only a weak

correlation between people's anxiety about a

particular risk and objective probability of death or

harm (Frost, Frank, & Maibach, 1997; Young,

Norman, & Humphreys, 2008). People with high

levels of health anxiety sometimes regard clinics as a

source of sickness rather than a resource for help.

People with excessive anxiety about infection tend to

engage in maladaptive safety behaviors (i.e.,

behaviors intended to keep themselves safe) such as

excessive hand washing and repeatedly seeking

reassurance from medical professionals. Excessive

handwashing can impair functioning in other areas of

life (e.g., occupational functioning), especially when

people devote hours per day to unnecessary

handwashing. Excessive reassurance-seeking (e.g.,

repeatedly and unnecessarily seeking assurances that

one is not sick) can add an unnecessary burden on the

healthcare system. Excessive reassurance-seeking

can also perpetuate health anxiety because (1) it

increases the risk that the person will obtain

conflicting medical information, (2) increases the risk

of iatrogenic interventions, and (3) reinforces the

person's view that their health is at risk (Taylor,

2019). The latter can occur, for example, when

unnecessary medical tests (e.g., laboratory tests) are

given in an attempt to reassure the anxious patient

The testing can be misinterpreted by the patient.

Reassurance-seeking can consist of persistent

searching the Internet for medical information

("cyberchondria"; (Mathes, Norr, Allan, Albanese, &

Schmidt, 2018), which increases the odds that the

person will be exposed to alarming, false information

(Taylor & Asmundson, 2004). People with excessive

health anxiety also tend to engage in "doctor

shopping"; that is, seeking consultations with

multiple physicians so as to reassure themselves that

they are not suffering from a serious disease. Doctor

shopping places an undue burden on the medical

system and increases the chances that the patient will

receive seemingly conflicting or confusing medical

advice (Taylor & Asmundson, 2004).

Beliefs and fears about diseases, just like diseases

themselves, spread through social networks. Beliefs

also influence the spread of infection. If there is

widespread belief in the importance of handwashing.

for example, then this will curtail the spread of

disease. In general, beliefs and fears are spread in

three main ways: (1) Information transmission, such

as by media reports (e.g., text, images) or verbal

information received from other people (e.g.,

rumors); (2) direct personal experiences, including

conditioning events (e.g., exposure to trauma); and

(3) observational learning (e.g., witnessing other

people acting frightened in response to some

stimulus). Information transmission and

observational learning are particularly relevant to the

spread of beliefs and fears through social networks (

Taylor, 2019).

A rumor, as the term is defined in the social

sciences, refers to a "story or piece of information of

unknown reliability that is passed from person to

person. Rumors are "improvised news", spreading

rapidly when the demand for information exceeds the

supply, as is the case during times of uncertainty

about important issues. Rumors may be spread if they

help people make sense of an ambiguous situation,

such as the possible threat of infection, and if rumors

offer guidance about how to cope with the perceived

risks (DiFonzo & Bordia, 2007). Rumors can arise

from anonymous sources, causing uncertainty about

the veracity of the information. Rumors can be spread

maliciously and to promote prejudice.

Social media have become a major source of

health information for people worldwide and have

become a global platform for outbreak and health risk

communication (Taylor, 2019). Social media are a

two-edged sword. They can rapidly disseminate

information and misinformation. They can fuel or

quell fears, and they can influence the spreading of

disease by influencing people's behavior. This

potentially raises problems with the spreading of

excessive fear. The same can be said for modern

communication technologies in general, including the

Internet. A large volume of misleading information is

posted on social media. Research indicates, for

example, that about 20-30% of You Tube videos

about emerging infectious diseases contain inaccurate

or misleading information (Tang et al., 2018).

Emotional contagion, including the spread of fear,

is a basic building block of human interaction,

allowing people to understand and share the feelings

of others by "feeling themselves into" another

person's emotions (Hatfield, Carpenter, & Rapson,

2014). Research shows that observational learning is

an important way in which emotions, including fears,

are spread (Bandura, 1986). Observational learning

involves the acquisition of information, skills, or

behavior by watching the performance of others.

Fears may be acquired via observational learning,

such as by seeing or hearing people express fear about

some issue, such as a possible pandemic.

Observational learning can include seeing fearful faces

or bodily postures and hearing frightened voices.

Systematic Literature Review on Mindset and the Benefits in Living New Normal Life

465

Contemporary methods for managing pandemics

are largely behavioral or educational interventions-

that is, vaccination adherence programs, hygienic

practices, and social distancing-in which

psychological factors play a vital role. Excessive

emotional distress associated with threatened or

actual infection is a further issue of clinical and public

health significance. Psychological factors are also

relevant for understanding and addressing the socially

disruptive behavioral patterns that can arise as a result

of widespread, serious infection. Four main methods

are used to manage the spread of infection: (1) Risk

communication (public education), (2) vaccines and

antiviral therapies, (3) hygiene practices, and (4)

social distancing (WHO, 2008, 2012; World Health

organization Writing Group, 2006). Psychological

factors play an essential role in the success of each of

these methods.

Pharmacological Treatments Vaccines and

antiviral medications are the primary

pharmacological methods for managing pandemic

influenza. The development of vaccines for infectious

diseases is a time consuming, costly business, with a

more than 90% failure rate (Gouglas et al., 2018).

Psychological factors, specifically mindset, are

important for understanding seemingly self-defeating

behaviors such as vaccination nonadherence (Taylor,

2019). In terms of influenza, people are unlikely to

seek vaccination if they (1) believe (accurately or not)

that they are unlikely to be exposed to an influenza

virus, (2) see themselves as being impervious to

infection, (3) do not perceive the infection to be a

serious problem, (4) perceive that there are significant

inconveniences or barriers to adherence, and (5) have

misgivings about the safety and efficacy of

vaccination (Taylor, 2019). People with very strong

beliefs about negative side effects may refuse to be

vaccinated even though they might also acknowledge

that the infection is potentially dangerous.

Vaccination hesitancy is a widespread, important

problem, even among medical practitioners and even

during times of pandemics. Various types of negative

attitudes and other psychological factors appear to

play a role, such as psychological reactance, PVD,

and injection phobia. Treating the attitudinal and

motivational roots of the problem may be vital during

the pandemic. Public education campaigns show

promise as do interventions targeting particular

problems such as injection phobia. Mandatory

vaccination as a requirement for employment may be

viable for medical practitioners and workers in other

sectors. It is unclear whether mandatory vaccination

would be viable on a community-wide level (Taylor,

2019).

Hygiene Practices Commonly recommended

hygiene practices include handwashing with soap or

hand sanitizer, covering sneezes/coughs (e.g.,

sneezing into the crook of one's arm), hand awareness

(i.e., refraining from touching one's eyes, nose or

mouth), cleaning household surfaces, and wearing

facemasks (WHO, 2008). Social Distancing refers to

interventions, either recommended or mandated by

health authorities, to reduce the probability that

infected people will spread disease to others

(Finkelstein, Prakash, Nigmatulina, Klaiman, &

Larson, 2010). Social distancing can include some or

all of the following, depending on the severity of an

outbreak: Quarantine of infected persons, school

closure, workplace closure, cancelling mass

gatherings such as sporting events and concerts,

closing recreational facilities (e.g., community

centers), closing non-essential businesses (e.g., clubs

and bars), cancelling non-essential domestic travel,

self-imposed isolation of uninfected people (e.g.,

remaining home, when possible), and border and

travel restrictions (World Health organization

Writing Group, 2006). Mindset predict a person's

proclivity to engage in the hygiene behaviors and

social distancing necessary for pandemic control.

Changing people’s mindset through the

communication message delivered communication

guidelines are as follows: 1. Announce the outbreak

early, even with incomplete information, so as to

minimize the spread of rumors and misinformation.

2. Provide information about what the public can do

to make themselves safer. 3. Maintain transparency to

ensure public trust 4. Demonstrate that efforts are

being made to understand the public's views and

concerns about the outbreak. 5. Evaluate the impact

of communication programs to ensure that the

messages are being correctly understood and that the

advice is being followed (WHO, 2005, 2008).

In the event of disaster such as a pandemic, a lack

of mental health and social support systems and a lack

of well-trained mental health professionals can

increase the risk that people will develop emotional

and other forms of psychological disorders (Taylor,

2019). A proactive response is required, involving a

rapid assessment of outbreak-associated

psychological stressors, for both civilians and

medical practitioners. But even at the best of times,

busy medical practitioners, such as primary care

physicians, often fail to detect psychological

disorders. The situation is even more challenging

during a pandemic, where there is an increase in the

number of sick people and likely staff shortages due

to illness. Accordingly, there need to be efficient

procedures for identifying people who are at risk for,

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

466

or actually suffering from, clinically significant

distress. Procedures are also needed for selecting

optimal interventions. The screen-and-treat method is

one such approach (Taylor, 2019).

Psychological interventions can be useful in the

early stages of a pandemic, when anticipatory anxiety

and worry are likely to be high, and in later stages,

especially where people are exposed to traumatic

events such as witnessing the death of friends and

loved ones. Psychological interventions can be useful

even after the pandemic has passed.

Mindsets outline the running account that’s taking

put in people’s heads. They guide the whole

interpretation process. In several studies, we probed

the way people with a fixed mindset dealt with

information they were receiving. We found that they

put a very strong evaluation on each and every piece

of information. Something good led to a very strong

positive label and something bad led to a very strong

negative label. The fixed mindset creates an internal

monologue that is focused on judging. Stronger

beliefs in the negative effects of stress, instead of the

positive effects of stress, were related with people’s

choice of emotional expression, which was in turn

associated with higher levels of irritation anger

(Horiuchi et al., 2018).

People with a growth mindset are too

continuously observing what’s going on, but their

inside monologue is not about judging themselves

and others in this way. Certainly, they’re delicate to

positive and negative information, but they’re

adjusted to its implications for learning and

constructive action. With growth mindset, people can

look more closely at the facts by asking: What is the

evidence for and against your conclusion? People

may also be encouraged to think of reasons of their

failure, and these may further temper their negative

judgment. In this way, people can get more realistic

and have more optimistic judgments to deal with their

situations in more adaptive ways and in turn generate

more positive and effective results.

4 CONCLUSIONS

In terms of theoretical insight, this study provides

results that mindset plays an important role in

understanding and addressing the socially disruptive

behavioral patterns that can arise as a result of

widespread, serious infection. Mindset are also

relevant for stress appraisals which will then

determine individual’s responses to stressors are

adaptive and lead to effective coping, or maladaptive

and lead to ineffective coping and compromised

health and functioning. Individuals with a growth

mindset were more likely to appraise a potential

stressor as challenging. These individuals were less

likely to be stressed, more likely to report positive

experiences, such as positive emotions, and use more

approach and active coping when they encountered

potentially stressful events. By contrast, individuals

with fixed mindset were more stressed, reported

negative experiences such as negative emotion, and

tend to use avoidant coping in stressful events.

REFERENCES

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and

action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs:

Prentice-Hall.

Birrell, J., Meares, K., Wilkinson, A., & Freeston, M.

(2011). Toward a definition of intolerance of

uncertainty: A review of factor analytical studies of the

intolerance of uncertainty scale. Clinical Psychology

Review, 31(7), 1198–1208. https://doi.org/doi:

l0.l016/j.cpr.2011.07.009

Bobevski, I., Clarke, D. M., & Meadows, G. (2016). Health

anxiety and its relationship to disability and service use:

Findings from a large epidemiological survey

Psychosomatic Medicine, 78(1), 13-25. Psychosomatic

Medicine, 78(1), 13–25. https://doi.org/doi: l0.l097/

PSY.0000000000000252

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Segerstrom, S. C. (2010).

Optimism. Clinical Psychology Review,30(7),879–889.

Cooper, K., Gregory, J. D., Walker, I., Lambe, S., &

Salkovskis, P. M. (2017). Cognitive behavior therapy

for health anxiety: A systematic review and meta-

analysis. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy,

45(2), 110–123. https://doi.org/doi:10.1017 /S13524

65817000510

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1987). Neuroticism, somatic

complaints, and disease: Is the bark worse than the bite?

Journal of Personality, 55(2), 299–316.

Crum, A. J., Akinola, M., Martin, A., & Fath, S. (2017).

The Role of Stress Mindset in Shaping Cognitive,

Emotional, and Physiological Responses to

Challenging and Threatening Stress. Anxiety, Stress, &

Coping, 30(4), 379–395. /https://doi.org/10.1080/106

15806.2016.1275585

Crum, A. J., Salovey, P., & Achor, S. (2013). Rethinking

stress: The role of mindsets in determining the stress

response. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 104(4), 716–733. https://psycnet.apa.

org/doi/10.1037/a0031201

Data-Franco, J., & Berk, M. (2013). The nocebo effect: A

clinician guide. Australian and New Zealand Journal of

Psychiatry, 47(7), 617–623. https://doi.org/doi:l0.1177

/0004867412464717

DiFonzo, N., & Bordia, P. (2007). Rumor psychology:

Social and organizational approaches. Washington,

DC: American Psychological Association.

Systematic Literature Review on Mindset and the Benefits in Living New Normal Life

467

Dong, E., Du, H., & Gardner, L. (2020). An interactive

web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time.

Correspondence, 20(5), 533–534. https://doi.org/10.10

16/S1473-3099(20)30120-1

Dweck, C. (2000). Self theories : Their role in motivation,

personality, and development psychology. New York:

Taylor and Francis Group.

Dweck, C. (2006). Mindset : The new psychology of

success. New York: Random House.

Dweck, C. (2017). Mindset: Changing the Way You Think

to Fulfil Your Potential(1

st

ed.). New York: Robinson

Ltd.

Dweck, C., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive

approach to motivation and personality. Psychological

Review, 95(2), 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-

295X.95.2.256

Eilenberg, T., Frostholm, L., Schroder, A., Jensen, J. S., &

Fink, P. (2015). Long-term consequences of severe

health anxiety on sick leave in treated and untreated

patients: Analysis alongside a randomised controlled

trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 32, 95–102.

https://doi.org/doi: 1 0.1 0 16 /j .janxdis.2015.04.001

Elliot, A., & Dweck, C. (2005). Handbook of competence

and motivation. New York: Guilford Press.

Finkelstein, S., Prakash, S., Nigmatulina, K., Klaiman, T.,

& Larson, R. (2010). Pandemic influenza: Non-

pharmaceutical interventions and behavioral changes

that may save lives. International Journal of Health

Management and Information, 1(1), 1–18.

Frost, K., Frank, E., & Maibach, E. (1997). Relative risk in

the news media: A quantification of misrepresentation.

American Journal of Public Health, 87(5), 842–845.

Frost, R. O., & Steketee, G. (2020). Cognitive approaches

to obsessions and compulsions: Theory, assessment,

and treatment. Oxford: Elsevier.

Gautreau, C. M., Sherry, S. B., Sherry, D. L., Birnie, K. .,

Mackinnon, S. P., & Stewart, S. H. (2015). Does

catastrophizing of bodily sensations maintain health-

related anxiety? A 14-day daily diary study with

longitudinal follow-up. Behavioral and Cognitive

Psychotherapy, 43(4), 502–512. https://doi.org/

doi:10.1017 /S1352465814000150

Gouglas, D., Le, T. T., Henderson, K., Kaloudis, A.,

Danielsen, T., Hammersland, N. ., & Rottingen, J. .

(2018). Estimating the cost of vaccine developent

against epidemic infectious diseases: A cost mini-

misation study. Lancet Global Health, 6(12), 1386-

1396. https://doi.org/doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30

346-2

Hagger, M. S., Koch, S., Chatzisarantis, N. L. D., & Orbell,

S. (2017). The common sense model of self-regulation:

Meta-analysis and test of a process model.

Psychological Bulletin, 143(11), 1117–1154. https://

doi.org/doi: l0.l037/buI0000118

Hatfield, E., Carpenter, M., & Rapson, R. L. (2014).

Emotional contagion as a precursor to collective

emotions. In C. Von Scheve & M. Salmela (Eds.),

Collective emotions: Perspectives from psychology,

philosophy, and sociology (pp. 108–122). Oxford

University.

Hedman, E., Lekander, M., Karshikoff, B., Ljotsson, B.,

Axelsson, E., & Axelsson, J. (2016). Health anxiety in

a disease-avoidance framework: Investigation of anxiety,

disgust and disease perception in response to sickness

cues. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(7), 868–878.

https://doi.org/doi:10.1037/abn0000 195

Horiuchi, S., Tsuda, A., Aoki, S., Yoneda, K., &

Sawaguchi, Y. (2018). Coping as a mediator of the

relationship between stress mindset and psychological

stress response: a pilot study. Psychology Research and

Behavior Management, 1(11), 47–54. https://doi.org/d

oi: 10.2147/PRBM.S150400

Ji, L. ., Zhang, Z., Usborne, E., & Guan, Y. (2004).

Optimism across cultures: In response to the severe

acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. Asian Journal of

Social Psychology, 7, 25-34., 2, 25-34. https://doi.org

/doi:1 0.1111/j.146 7 -839X.2 004.00132.x

Kam, C., & Meyer, J. P. (2012). Do optimism and

pessimism have different relationships with personality

dimensions? A re-examination. Personality and

Individual Differences, 52(2), 123–127. https://doi

.org/doi:1 0.1016/j. paid.2011.09.011

Keech, J. J., Hagger, M. S., & Hamilton, K. (2021).

Changing stress mindsets with a novel imagery

intervention: A randomized controlled trial. Emotion,

21(1), 123–136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1

037/emo 0000678

Kim, H. K., & Niederdeppe, J. (2013). Exploring optimistic

bias and the integrative model of behavioral prediction

in the context of a campus influenza outbreak. Journal

of Health Communication, 18(2), 206–222. https://

doi.org/doi:1 0.1080/10810730.2012.688247

Kring, A. M., & Sloan, M. D. (2010). Emotion regulation

and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic approach to

etiology and treatment. New York: Guilford Press.

Leventhal, H., Phillips, L. A., & Burns, E. (2016). The

common-sense model of self-regulation (CSM): A

dynamic framework for understanding illness self-

management. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 39(6),

935-946.https://doi.org/doi:10.1007/s10865-016-9782-2

Levi, J., Segal, L. M., St. Laurent, R., & Lieberman, D. A.

(2010). Fighting flu fatigue. Retrieved April 7, 2019,

from healthyamericans. org/ assets / fil es /TF AH 2 010

FI uBriefFI NAL. pdf.

Loeb, I. S., & Dweck, C. (1994). Beliefs about human

nature as predictors of reaction to victimization. The

Annual Convention of the American Psychological

Society. Washington, DC.

Makridakis, S., & Moleskis, A. (2015). The costs and

benefits of positive illusions. Frontiers in Psychology,

6. https://doi.org/doi:l0.3389/fpsyg.2015.00859

Mathes, B. M., Norr, A. M., Allan, N. P., Albanese, B. ., &

Schmidt, N. B. (2018). Cyberchondria: Overlap with

health anxiety and unique relations with impairment,

quality of life, and service utilization. Psychiatry

Research, 261, 204-211. doi:l 0.1016/j. psychres.2

018.01.002. Psychiatry Research, 261, 204-211.

https://doi.org/doi:l 0.1016/j. psychres.2 018.01.002

McEvoy, P. M., & Mahoney, A. E. J. (2013). Intolerance of

uncertainty and negative metacognitive beliefs as

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

468

transdiagnostic mediators of repetitive negative

thinking in a clinical sample with anxiety disorders.

Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27(2), 216-224.

https://doi.org/doi: 1 0.1 0 16 /j .janxdis. 2 0 13.01.006

National Research Council. (2004). How students learn

mathematics in the classroom. Washington, DC:

National Academies Press.

Norris, A. L., & Marcus, D. K. (2014). Cognition in health

anxiety and hypochondriasis: Recent advances. Current

Psychiatry Reviews, 10(1), 44–49. https://doi.org/

doi:10.2174/1573400509666131119004151

Norton, P. J., & Paulus, D. J. (2017). Transdiagnostic

models of anxiety disorder: Theoretical and empirical

underpinnings. Clinical Psychology Review, 56, 122–

137. https://doi.org/doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.03.004

Salkovskis, P. M., & Warwick, H. M. C. (2001). Meaning,

misinterpretations, and medicine: A cognitive-

behavioral approach to understanding health anxiety

and hypochondriasis. In V. Starcevic & D. R. Lipsitt

(Eds.), Hypochondria (pp. 202–222). New York:

Oxford University Press.

Schoenfeld, A. (2007). Assessing mathematical

proficiency. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Scott, M. ., & Ghinea, G. (2014). Measuring enrichment:

the assembly and validation of an instrument to assess

student self-beliefs in CS1. ICER ’14: Proceedings of

the Tenth Annual Conference on International

Computing Education Research., 123–130. https://doi.

org/DOI:10.1145/2632320.2632350

Sharot, T., Korn, C. W., & Dolan, R. J. (2011). How

unrealistic optimism is maintained in the face of reality.

Nature Neuroscience, 14(11), 1475–1479. https://doi.

org/doi: l0.l038/nn.2949

Sunderland, M., Newby, J. M., & Andrews, G. (2013).

Health anxiety in Australia: Prevalence, comorbidity,

disability and service use. British Journal of Psychiatry,

202(1), 56–61. https://doi.org/doi:1 0.1192/bjp.bp.lll.l0

3960

Taha, S., Matheson, K., Cronin, T., & Anisman, H. (2014).

Intolerance of uncertainty, appraisals, coping, and

anxiety: The case of the 2009 HINl pandemic. British

Journal of Health Psychology, 19(3), 592–605.

https://doi.org/doi:10.1111/bjhp.12058

Tang, L., Bie, B., Park, S. E., & Zhi, D. (2018). Social

media and outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases: A

systematic review of literature. American Journal of

Infection Control, 46(9), 962–972. https://doi.org/doi: 1

0.1016 /j.aj ic.2 018.02.010

Taylor, S. E., & Brown, J. D. (1988). Illusion and well-

being: A social psychological perspective on mental

health. Psychological Bulletin, 103(2), 193–210.

https://doi.org/doi: l0.l037 /0033- 2909.103.2.193

Taylor, S. (2017). Clinician’s guide to PTSD (Second).

New York: Guildford.

Taylor, S. (2019). The Psychology of pandemics: Preparing

for the next global outbreak of infectious disease.

Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Taylor, Steven, & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2004). Treating

health anxiety. New York: Guilford. New York:

Guilford Press.

Tyrer, P., & Tyrer, H. (2018). Health anxiety: Detection and

treatment. British Journal of Psychiatry Advances,

24(1), 66–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/

bja.2017.5

Weiner, B. (2005). Motivation from an attributional

perspective and the social psychology. In Handbook of

Competence and Motivation (pp. 73–84). New York:

Guilford Press.

Wheaton, M. G., Abramowitz, J. S., Berman, N. C.,

Fabricant, L. E., & Olatunji, B. O. (2012).

Psychological predictors of anxiety in response to the

HINl (swine flu) pandemic. Cognitive Therapy and

Research, 36(3), 210–218. https://doi.org/doi:l0.l007

/s10608-011-9353-3

WHO. (2005). WHO checklist for influenza pandemic

preparedness planning. Geneva.

WHO. (2008). WHO outbreak communication planning

guide. Geneva.

WHO. (2012). Vaccines against influenza WHO position

paper. Weekly Epidemiological Record, 87, 461–476.

World Health organization Writing Group. (2006).

Nonpharmaceutical interventions for pandemic

influenza, national and community measures.

Emerging infectious diseases.

Young, M. E., Norman, G. R., & Humphreys, K. R. (2008).

Medicine in the popular press: The influence of the

media on perceptions of disease. PLOS ONE, 3, E3552.,

3552(3). https://doi.org/Doi: l0.1371/journal.pone.000

3552

Systematic Literature Review on Mindset and the Benefits in Living New Normal Life

469