The Role of Religious Orientation and Ethical Ideologies in

Environmental Concerns amongst Teachers and School Staff in East

Java, Indonesia

Dexon Pasaribu

1a

, Pim Martens

2b

and Bagus Takwin

2c

1

Maastricht Sustainable Institute, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands

2

Department of Social Psychology, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia

Keywords: Religious Orientation, Ethical Ideology, Environmental Apathy, Environmental Concerns.

Abstract: Several studies show that more often than not, religion hinders the preservation awareness and efforts towards

the ecology. Others, however, have found that the belief in God or the identification with a particular religion

is not associated with measures for environmental concern. This study investigates how Allport’s intrinsic

personal (IP) and extrinsic social (ES) religious orientation and Forsyth’s ethical ideologies of idealism and

relativism relate to the measures of environmental concerns using ecocentric (EM), anthropocentric motives

(AM) and general environment apathy (GEA). Using quantitative design, we survey a total of 929 school

teachers and staff from 37 schools in East Java. Multiple regression is applied to analyse the data. Results

suggest mixed results whereby a higher IP more often leads to a lower GEA and a higher EM and AM. On

the other hand, relativism and ES consistently relate to a higher AM and a higher GEA. We also identify

different components of religious orientation which correlate significantly with idealism and relativism,

suggesting that individuals’ religious orientation may closely relates to their ethical belief and decision.

Lastly, several approaches to interpret the results along with several significant demographic and other

determinants with each of their limitations, are discussed.

1 INTRODUCTION

Religion has barely been featured amongst key

anthropogenic factors causing environmental

degradation (Bauman, Bohannon, & O’Brien, 2010);

at least not until after White's (1967) thesis about

religion gained sufficient attention from the scientific

community, where much of the later research would

then assume that religion and ecology are interrelated.

Several studies show that more often than not,

religion hinders the awareness of and efforts for

environmental sustainability, where it depresses

concern about the environment (Arbuckle & Konisky,

2015; Barker & Bearce, 2013; Muñoz-García, 2014).

Others, however, have found that the belief in God or

the identification with a particular religion is not

associated with measures of environmental concern

(Boyd, 1999; Hayes & Marangudakis, 2000, 2001;

Smith & Leiserowitz, 2013).

There are several possible reasons for these mixed

results. One reason might stem from how each study

addresses different aspects and properties of religion

in measuring religious value, such as religious

scriptures, contents and interpretation (Haq, 2001;

McFague, 2001; Tirosh-Samuelson, 2001), or

communication framing (Smith & Leiserowitz, 2013;

Wardekker, Petersen, & van der Sluijs, 2009).

Another reason might reside in how various studies

differ in how they define religiosity, religiousness or

religious belief. Gallagher & Tierney (Gallagher &

Tierney, 2013) argue that religiosity and religiousness

are interchangeable as far an individual’s conviction,

devotion and veneration towards a divinity is

concerned. However, religiosity or religiousness can

be broadly or narrowly formulated using differing

aspects such as (1) human cognitive aspect (beliefs,

knowledge), (2) affect, which relates emotions to

religion, and (3) behavior, such as time spent praying

or reading religious texts, attendance, or affiliation

(Cornwall, 1989). Thus, differing foci and aspects

produced various operationalizations of religiosity,

such as religious orthodoxy (Fullerton & Hunsberger,

1982; Hunsberger, 1989), typology (Glock & Stark,

1965), fundamentalism (Kellstedt & Smidt, 1991;

Pasaribu, D., Martens, P. and Takwin, B.

The Role of Religious Orientation and Ethical Ideologies in Environmental Concerns amongst Teachers and School Staff in East Java, Indonesia.

DOI: 10.5220/0010755400003112

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences (ICE-HUMS 2021), pages 551-573

ISBN: 978-989-758-604-0

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

551

McFarland, 1989), and religious orientation (Allport,

1966; Allport & Ross, 1967; Donahue, 1985). For

religious belief, this study views Allport’s religious

orientation fits well in defining the interchangeably-

used religiosity or religiousness, as far as it

approaches beliefs, knowledge and affectation of

intrinsic, extrinsic personal and extrinsic social

motivation in engaging in religious activities. In

detail, Allport’s religious orientation consists of

intrinsic religious orientation, where religion is

deeply personal to the individual, such as the

commitment to a religious life and living out his/her

religion; extrinsic personal religious orientation, with

religion being a source of peace safety and comfort,

which is a direct result of participating in religious

activity; and, finally, extrinsic social religious

orientation, where the emphasis is placed on religion

as membership in a powerful in-group, providing

protection, consolation or social status, and enabling

religious participation (Allport & Ross, 1967; Fleck,

1981; Genia & Shaw, 1991; Kahoe & Meadow, 1981;

Maltby, 1999).

The present study proposes to address religion as

a major driver of ethics and how it relates to attitudes

towards the natural environment preservation and

sustainability. Studies examining the relationship

between religious belief and ethical ideologies

(Cornwell et al., 2005; Watson, Morris, Hood,

Milliron, & Stutz, 1998; Weaver & Agle, 2002)

provide evidence that ethical ideologies facilitate

broader philosophical coverage corresponding to

religious values and beliefs. Several studies argue that

general spiritual principles and values are largely

related to ethics (Cornwell et al., 2005; Jackson,

1999; Skipper & Hyman, 1993), indicating that

religiosity significantly correlates with Forsyth

(1980) idealist and anti-relativist ethical ideologies

(Barnett, Bass, & Brown, 1996; Watson et al., 1998).

Cornwell et al. (1994) found that religion has some

effect on ethical positions. Austrian Christians are

significantly less idealistic and relativistic than all

other religions, even with other Christians from the

United States and Britain. They argued that there are

some ethical convergence between religions. In

another study, Barnett et al. (1996) concluded that

religiosity correlates positively with a non-relativist

ethical ideology. Closely similar with them, Watson

et al. (1998) argued that religious intrinsicness or

religious intrinsic personal orientation is associated

with the idealism and antirelativism of an absolutist

ethical position. They argued that intrinsic

commitments to religion may simply mean that

certain beliefs are absolutely non-negotiable (Watson

et al., 1998, p. 5). In Forsyth's (1980) terms, this

absolutistic way of thinking type is the result when

people strongly believe that moral decision should be

guided by an universal governing principle (low

relativism) rather than by personal or situational

analysis (high relativism) while also convinced that

ethical behavior will always lead to positive

consequences.

Forsyth (1980) ethical ideologies consist of two

components, namely, ethical idealism and ethical

relativism. An idealist thinks that ethical behavior

will always lead to positive consequences, while a

relativist rejects universal moral principles, instead

believing that moral decisions should be based on a

personal or situational analysis (Forsyth, 1980).

Nonetheless, the role religion plays to the concerns

for ecology is as yet still unclear. Studies on ethical

ideologies provide clear evidence where religiosity

significantly correlates with idealism and anti-

relativism (Barnett et al., 1996; Watson et al., 1998).

Thus, combining results from above mentioned

studies, the present study targets religious orientation

and ethical ideologies as the main variables to explore

how both religiousness and ethic relate and interact

with concerns for the natural environment

preservation. For the first working hypothesis, this

study predicts that intrinsic personal religious

orientations has a positive correlation with ethical

idealism and a negative correlation with relativism.

For sustainability and the attitude or concerns to

the natural environment, White (1967) arguments

highlight the urge for sustainability in responding

development and growth at that time. White (1967)

argues that, to some extent, the current ecological

crisis is due to the disconnection of nature and

spirituality often promoted by religion which gives

the human species rights and dominance to exploit

nature which forms the basis for exploiting the natural

world. The concept of Sustainable Development first

became prominent in the 1980s with its most

mainstream definition of “development that meets the

needs of the present without compromising the ability

of future generations to meet their own needs”

(Brundtland, 1987). From this definition, three pillars

approach derived consisting social sustainability,

economic sustainability, and environmental

sustainability. In its progression, the latter mainly

become the domain of sustainability sciences while

the former two (namely, economic and social

sustainability) have mainly become the domain of

development studies.

In contrast, despite efforts to incorporate research

results from both development and sustainability

disciplines, a complete integration to achieve

sustainable development is facing numerous

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

552

challenges. According to Goodland & Daly (1996),

one of the problems is because of the difference in

priorities in both disciplines. While the development

goals are fundamentally important, they are quite

different from the goals of environmental

sustainability, which is the unimpaired maintenance

of human life-support systems Goodland (1995, p. 5).

Goodland & Daly (1996) differentiate, at the very

least, four kinds of capital which are human-made

capital (the one usually considered in financial and

economic accounts); natural capital (the stock of

environmentally provided assets such as soil,

atmosphere, forests, water, wetlands); human capital

(investments in education, health and nutrition of

individuals); and social capital (the institutional and

cultural basis for a society to function). Goodland &

Daly (1996) challenge the notion of throughput

growth in the context of finite earth, in which as a

subsystem of the finite and non-growing earth, the

economy must eventually adapt to it. To emphasize

this finite earth, they further challenge the economic

concept of ‘income’ arguing that “any consumption

that is based on the depletion of natural capital should

not be counted as income.” Prevailing models of

economic analysis tend to treat consumption of

natural capital as income and therefore tend to

promote patterns of economic activity that are

unsustainable. Consumption of natural capital is a

liquidation, the opposite of capital accumulation”

(Goodland & Daly, 1996, p. 1005). Thus,

environmental sustainability requires maintaining

natural capital; and to understand it includes defining

"natural capital" and "maintenance of resources" (or

at least "non-declining levels of resources").

Sustainability means maintaining environmental

assets, or at least not depleting them. Goodland &

Daly (1996) argue that the limiting factor for much

economic development has become natural capital as

much as human-made capital. “In some cases, like

marine fishing, it has become the limiting factor—

fish have become limiting, rather than fishing boats.

Timber is limited by remaining forests, not by

sawmills; petroleum is limited by geological deposits

and atmospheric capacity to absorb CO2, not by

refining capacity” (Goodland & Daly, 1996, p. 1005).

In this sense of finite natural capital, they also

introduced cultivated natural capital (such as

agriculture products, pond-bred fish, cattle herds, and

plantation forests)—the combination of natural and

human-made capital— which dramatically expands

the capacity of natural capital to deliver services.

Nevertheless, Goodland & Daly (1996) concludes

that eventually, natural capital will limit this

cultivated natural capital.

In support to Goodland (1995) and Goodland &

Daly (1996), the present study bring forth the

dilemma between sustainability science and

development studies whereby they haven’t yet

reached consensus on the attainable priorities path-

ways on whether to reach environmental

sustainability or more anthropocentric (social and

economic) sustainability. Similarly, Thompson &

Barton (1994) formulated and developed two

underlying motives of environmental attitudes, which

are ecocentrism—valuing nature for its own sake; and

anthropocentrism—valuing nature because of the

material or physical benefits it provides; with an

additional dimension of general apathy towards the

environment (Gardner & Stern, Stern & Dietz,

Oksanen, as cited in Bjerke & Kaltenborn, 1999).

Thompson & Barton (1994) proposed that the

motives and values which underlie environmental

attitudes are of great significance in which the same

positive attitude to the importance and conservation

of the natural environment might come from

ecocentric or anthropocentric motives, or even both,

making the importance of general environment

apathy scale as one strong potential cross-section

predictor for both environmental attitude and

acceptability of harming animal. This is especially

relevant after Bjerke and Kaltenborn (1999) further

riddled this topic when they found that ecocentric

motives scored differently to different job-groups

categorization when valuing carnivores animals

compared to herbivores. In their study of ecocentric

and anthropocentric motives relationship to attitudes

towards large carnivores, Bjerke and Kaltenborn

(1999) highlighted that high ecocentrism and low

apathy to the natural environment only specifically

resonate to those research biologist and wildlife

managers groups who scored positive attitude

towards carnivores. Thus as the second working

hypothesis, the present study proposes Thompson &

Barton's (1994) general environmental apathy scale

will negatively correlated with ecocentric and

anthropocentric motives.

While there are ample studies connecting religion

either to ethical ideologies or to environmental

sustainability, studies examining both ethical

ideologies and environment sustainability at once, are

lacking. One exception is in the field of animal

welfare, where there are a growing number of

investigations confirming positive correlation

between ethical ideologies and public’s attitudes

towards animals (Galvin & Herzog, 1992; Herzog &

Nickell, 1996; B Su & Martens, 2017; Bingtao Su &

Martens, 2018; Wuensch, Jenkins, & Poteat, 2002).

Studies of ethical ideologies and attitudes towards

The Role of Religious Orientation and Ethical Ideologies in Environmental Concerns amongst Teachers and School Staff in East Java,

Indonesia

553

animals and animal protection demonstrate that

public’s attitudes towards animals or animal

experiments are related to their ethical perspectives.

One study investigating the role of idealism and

relativism in research using animal in the United

States demonstrates that idealism correlates

negatively and relativism correlates positively to

support for animal research (Wuensch & Poteat,

1998). They argued that idealists often express

greater moral concern for how animals are utilized

than their relativist counterparts (Wuensch & Poteat,

1998). Specifically for Forsyth’s idealism, later

studies provide more evidence that positive attitudes

to animals correlate positively to ethical idealism,

where people's moral idealism significantly

influences their attitudes towards animals (Galvin &

Herzog, 1992; B Su & Martens, 2017). Galvin &

Herzog (1992) found that ethical idealism relates

positively to a higher concern for animal use.

Through their research about the effectiveness of

materials designed to sway public’s opinion about

biomedical research using animals, Herzog & Nickell

(1996) would later add that compared to males and

those low in ethical idealism, females and subjects

high in moral idealism rate higher effectiveness to

those research materials and advertising that reject

animal use in biomedical research (anti-animal

research materials) (p. 9). More recent studies by B

Su & Martens (2017, 2018) also confirmed these

results, showing that higher idealism scorers are more

likely to have a more positive attitude to animals and

a lower acceptability for harming animals. The more

those individuals consider their ethical behavior

would always lead to desirable consequences, the

more they appreciate animals (B Su & Martens,

2017). At the very least, it has been consistently

proven that ethical idealism lowers acceptability for

harming animals, instead encouraging more positive

attitudes towards animal (Galvin & Herzog, 1992; B

Su & Martens, 2017; Bingtao Su & Martens, 2018).

There was not much support for the significance of

relativism except only from Wuensch & Poteat

(1998) who found that higher score of relativism

relates to higher support for research using animals.

However B Su & Martens (2017, 2018) slightly

deviate from older studies (Galvin & Herzog, 1992;

Herzog & Nickell, 1996) whereby they find that high

scorers of ethical relativism are more likely to have a

more negative attitude towards animals only in China

(B Su & Martens, 2017), but not in their Dutch

sample (Bingtao Su & Martens, 2018). B Su &

Martens (2017, 2018) argued that the differences

between both samples may stem from the difference

between being a developed and developing country,

respectively. However, despite this slight difference,

most animal welfare studies examining the role of

ethical ideologies showed that ethical idealism and

relativism relates to people’s attitude towards and

acceptability for harming animal. Thus, incorporating

previous research results from the field of animal

welfare, this study tries to carefully simulate for

whether those findings from animal welfare studies

also replicate to the attitude to the natural

environment preservation.

Bjerke and Kaltenborn (1999) argued that positive

attitudes towards animals may stem from either

anthropocentric or ecocentric motives or both. The

present study considers these ecocentric and

anthropocentric value and motives to be particularly

important partly as the results of ethical idealism and

ethical relativism ideologies. Borrowing findings

from previously mentioned animal welfare studies

(Galvin & Herzog, 1992; B Su & Martens, 2017;

Bingtao Su & Martens, 2018; Wuensch & Poteat,

1998), this study tries to extend those results into a

more general environmental preservation concerns. A

person highly views that his/her ethical behavior will

always lead to positive consequences and who also

firmly believes that there are universal moral

principles (low relativism), may weighs more to

higher environmental concerns in perceiving his/her

surroundings. On the other hand, a person who views

that his/her ethical behavior will not always lead to

positive consequences (low idealism) while also

firmly believes that there are no governing universal

moral principles (high relativism) may weigh in more

to a lower environmental concerns. Therefore, the

third working hypothesis of this study predicts that

higher environmental concern correlates positively

with ethical idealism and negatively with relativism.

In more detail, this study proposes that individual

with higher environmental concerns are those

participants who scored a lower general

environmental apathy and a higher ecocentric

motives in valuing the natural environment. And

such, taking together as well as independently, lower

general environment apathy and higher ecocentric

motives should relate to a higher idealism and a lower

relativism. Thus, for the third hypothesis the opposite

should also true, whereby a higher general

environmental apathy and a lower ecocentric motives

in valuing the natural environment should relate with

a lower idealism and a higher relativism.

In addition, using the context of White's (1967)

perspectives, the present study aims to further

examine the relation between religion (i.e. both as

cognitive belief and ethical judgment) and the attitude

to the importance and conservation of the natural

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

554

environment. Allport & Ross (1967) religious

orientation construct has been chosen to measure

religious intrinsic, extrinsic personal and extrinsic

social orientations. In later developments of religious

orientation, the dimension of extrinsic social motives

has been added (Donahue, 1985; Maltby, 1999;

Trimble, 1997). Extrinsic social religious orientation

addresses how individuals practice religion more as

an instrument for social gain such as membership in

a powerful in-group, providing protection,

consolation or social status, and enabling religious

participation. The extrinsic social religious

orientation is more closely related to the social

identity in-group membership concept (Henri Tajfel,

1974, 1981; Turner, 1975) which introduce

instrumental views of religion for social gain whereby

religious belief systems are used to obtain desirable

outcomes that may unnecessarily be ethical or

unethical. On one hand, the ethical means for social

gain may very much corresponds to the concept of

ethical idealism where ethical behaviour is believed

will always bring positive outcome. However, on the

other hand, should there be unethical means for social

gains, it may relate to lower idealism, and higher

relativism in which a person strongly believe that

there is no universal moral standard, and therefore,

moral decisions should be based on the personal or

situational analysis. In this sense, we are carefully

posing the working hypothesis for the relationship

between extrinsic social religious orientation and

ethical ideologies. Therefore, as the fourth

hypothesis, we predict that higher extrinsic social

religious orientation relates to a lower idealism and

higher relativism. This hypothesis is an extension

from the first hypothesis, in which we seek to find

evidence of how religious orientation relates to the

natural environment preservation attitude by

examining how it correlates to ethical ideologies.

Lastly, as previously in the third hypothesis we

predict that higher relativism relates to a higher

environmental apathy, for the fifth hypothesis, this

study expects that a higher extrinsic social religious

orientation will also relate to a higher environmental

apathy.

It is important to emphasize that this study is not

theological in nature and is not describing Islamic

religious worldview of the natural environment. As

previously discussed, this study approaches the

religious belief through Allport & Ross' (1967)

religious orientation. Specifically for extrinsic social

religious orientation (ES), we argue that it strongly

overlaps with the social identity in-group

membership theory (Henri Tajfel, 1974, 1981;

Turner, 1975) especially in the concept of social

category. In this study, we view that the extrinsic

social religious orientation echoes a social category

notion that offers a sense of identity which

individuals identify with and act in the ways they

believe represent their group’s identity (Blumer,

1958; Henry Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Individuals who

identify themselves as Muslims are more likely to

behave in accordance with the typical behaviours of

fellow Muslims. Therefore, this study purposefully

selects the population in East Java province,

considering that it represents some of the oldest, most

influential Islamic communities and organizations,

whilst also being the province with the most diverse

Islamic denomination.

The province of East Java is the birthplace of

Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), the largest Islamic mass

organization in Indonesia. It has approximately 40

million members throughout the nation and its

influence is not merely at the regency-level but also

at the national (Anwar, 2019). Secondly, East Java is

well-known for its long history of Islamic boarding

schools. Pesantren Darul Ulum is one of the oldest

and most distinguished in Jombang, East Java

(Turmudi, 2006). Thirdly, East Java offers an

interesting segment of the political constellation in

Indonesia. Its political influence at the national level

has been prominent since the making of the nation

(Bush, 2009). Two of the most renowned instances

were the appointment of Abdurrahman Wahid as the

fourth President of Indonesia (1999-2001) and the

appointment of Ma’ruf Amin as the current

Indonesian vice president (took office in 2019), both

of whom have strong ties to Nahdlatul Ulama in East

Java. All in all, the above reasons foster East Java as

one of the most relevant candidate-grounds for

scrutinizing the relationship between religiousness

and the attitudes held towards the importance of

natural environment preservation; moreover, due to

the religious groups’ prevalence in East Java, we

should point out that our respondents are likely to be

Muslims. Regardless of all the above, however close

a representation East Java is of the everyday major

religious worldview in Indonesia, the present study

avoids over-generalization of the results representing

the whole country.

This study targeted school teacher and staff in

viewing that as an institution, both public and private

schools are subjects to nation-wide education

curriculum whereby collected data may generally

capture a nation-wide curriculum’s learning goals

(Swirski, 2002) relevant to natural environment

protection. However, there were also a lengthy

discussions about educators roles as transformative

intellectuals rather than as nation-state agent teaching

The Role of Religious Orientation and Ethical Ideologies in Environmental Concerns amongst Teachers and School Staff in East Java,

Indonesia

555

nation-state learning goals (Leite, Fernandes, &

Figueiredo, 2020; Muff & Bekerman, 2019; Tan,

2016). Also, taking some roles and responsibilities of

a parent (loco parentis), teacher may be as well

provide assistance and insight on moral, political,

religious and ethical issues for their students (Grubb,

1995) as one study hinted that teachers act as role-

models for the students and influence their students’

political attitudes (Bar-Tal & Harel, 2002).

In other study related to transformative agency,

teachers’ inclusive practices, moral purposes,

competence, autonomy and reflexivity (Pantić, 2015)

are important factors to act as an agent of change. The

duality of being transformational agents while also

fulfilling their obligatory role to implement the

nation-state education curriculum agenda, Muff &

Bekerman (2019) argued that teachers mediate their

roles between the different demands that of the civic

education politics impose to them by navigating

elegantly both in producing hegemonic discourse and

in fostering ways to rebel against and draw counter-

hegemonic strategies in their classroom practice.

Thus, this study viewed that having teachers as the

participants for the research would capture some

dynamics of interlocking roles at play. To name a

few, the nation-state curriculum goals, teachers’

beliefs, moral purposes, reflexivity and awareness in

responding to the nation-state curriculum, and their

combined roles as transformative intellectuals, more

or less, are the dynamics reflected in classroom

discourses. Teachers attitudes to the preservation and

protection to the natural environment may best

represent the nation’s sets of environmental policy

and the younger generation’s perspective.

Lastly, we also emphasize the demographic

determinants commonly suggested in most studies

about religion and ethical ideologies, such as gender,

age, household income, education, pet ownership,

religious organization affiliation, meat consumption

(B Su & Martens, 2017; Bingtao Su & Martens,

2018). We will therefore closely scrutinize these

important demographic or other determinants in our

analysis.

2 MATERIAL AND METHODS

This research targeted Muslim teachers and school

staff in the province of East Java, Indonesia, using

cluster sampling, whereby a paper and pencil survey

of teachers was conducted. Survey participation

invitations were sent to 67 schools (ranging from

junior to senior high schools). The survey invitation

emphasizes that it is important for the school to

provide a balanced proportion of male and female

teachers or school staff. Total of 37 schools, from 10

districts of East Java, replied and agreed to

participate, providing 1007 participants. However,

only 929 participants were analysed due to removing

78 participants because of incomplete and unengaged

answers (see section 3.2).

All the questionnaires in the survey were

originally in English. We then translated them to

Indonesian. The method of translation and adaptation

was using expert judgement and back translation. The

questionnaires were translated to Bahasa Indonesia

and sent to experts for evaluation and finalization of

the translation. After corrections, the questionnaires

were translated back to English by three Indonesian

academicians from Universitas Indonesia. Back-

translated items that are very similar to their English

language origin are retained, and the remaining are

modified or deleted.

The set of questionnaires consist of four sections.

In the first section, we asked a variety of important

determinants and demographic details such as birth

year (age), gender, highest level of education

completed, their household composition (for

example, single, married, or widow(er), with children

or not), place of residence (rural or urban), type of

house (apartment, live with parents, etc.), their

opinion regarding the importance of

religion/spirituality in their lives, their experience or

participation in religious organization, household

income, pet ownership, kinds of pet, their weekly

frequency of meat consumption, and the frequency of

visiting public zoos or aquariums in a year.

In the second section, Thompson & Barton's

(1994) Ecocentric-Anthropocentric Scale of

Environmental Attitude (EASEA) is used to measure

environmental motives and apathy. There are 30-

items rated on a five-point scale ranging from one,

extremely disagree, to five, extremely agree. In order

to translate and adapt this questionnaire into

Indonesia language, we feel necessary to translate a

question into two forms, which in turn make the

resulting Indonesian version to total 31-items. A high

score on a question indicates a high level of

agreeableness for the topic, which basically consist of

three dimensions. The first measures ecocentric

motive where nature is valued for its own sake, and

therefore, judged that it deserves protection because

of its intrinsic value. The type of issue statement

being asked are, for example, ‘I can enjoy spending

time in natural settings just for the sake of being out

in nature,’ ’ Sometimes animals seem almost human

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

556

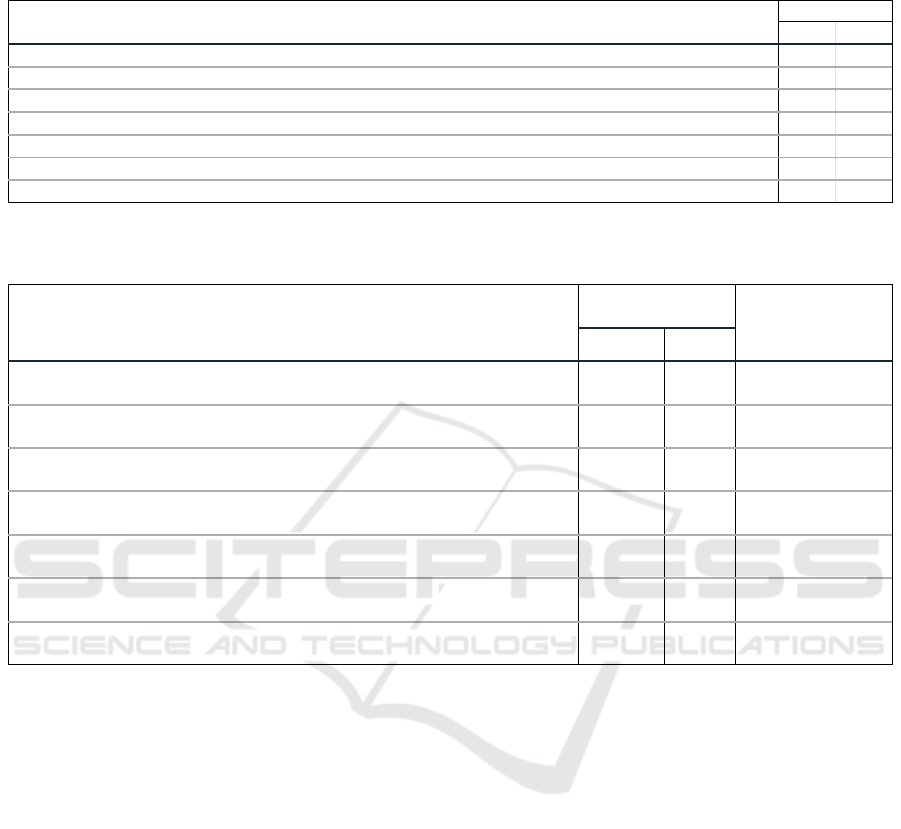

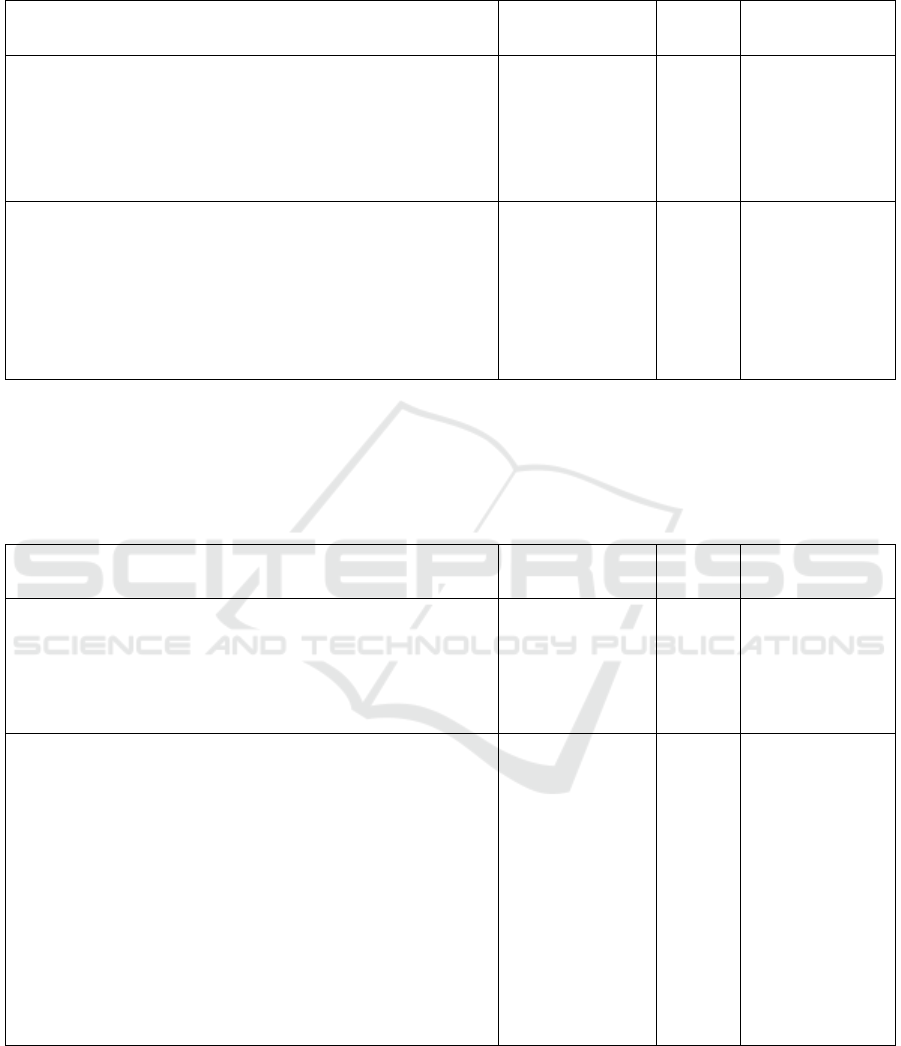

Table 1: EASEA-ecocentric rotated factor matrix.

Items

Facto

r

a

1 2

ECCANTH02 I en

j

o

y

s

p

endin

g

time in natural settin

g

s

j

ust for the sake of bein

g

out in nature .464

ECCANTH12 I need time in nature to be happ

y

.608

ECCANTH15 Sometimes when I am unhappy I find comfort in nature .622

ECCANTH26 Being out in nature is a great stress reducer for me .666

ECCANTH28 One of the most im

p

ortant reasons to conserve is to

p

reserve wild areas .428

ECCANTH30 Sometimes animals seem almost human to me .616

ECCANTH31 Human are as much a

p

art of the ecos

y

stem as other animals .612

Extraction Method: Principal Axis Factoring. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization.

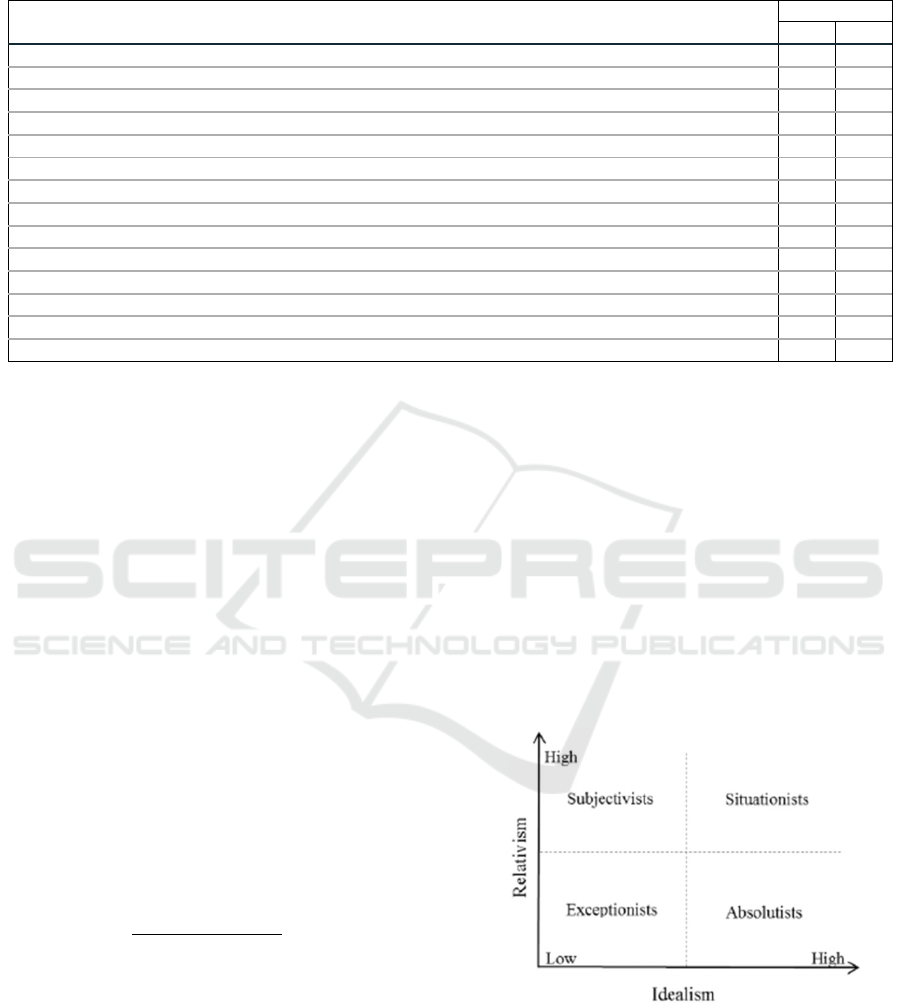

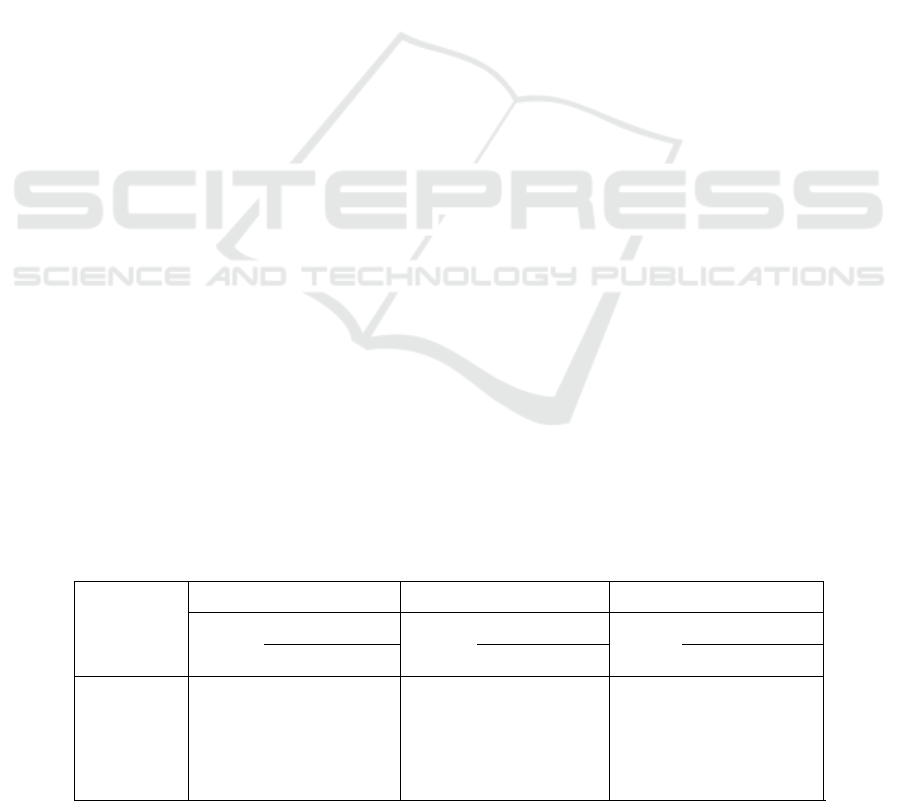

Table 2: EASEA-anthropocentric rotated factor matrix.

Items

Model 1 (using

ei

g

en value > 1

)

Model 2 (as one

factor)

1 2

ECCANTH04 The worst thing about the loss of the rain forest is that it will

restrict the develo

p

ment of new medicines

.771 Delete

ECCANTH05 The worst thing about the loss of the rain forest is that it will

reduce plants and animals which benefit for human kin

d

.497 .414

ECCANTH20 The most important reason for conservation is human

survival

.510

.429

ECCANTH22 Nature is important because of what it can contribute to the

p

leasure and welfare of humans

.611

.564

ECCANTH25 We need to preserve resources to maintain a high quality of

life

.600 .567

ECCANTH27 One of the most important reasons to conserve is to ensure a

continued hi

g

h standard of livin

g

.429 .563

ECCANTH29 Continued land development is a good idea as long as a high

quality of life can be preserve

d

.412 .501

Extraction Method: Principal Axis Factoring. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization.

to me,’ or ‘Nature is valuable for its own sake.’ There

are total of 12 questions in the ecocentric dimension.

However, after principal axis factoring factor

analysis, this study not only reduced the items to only

seven items, but also found that the ecocentric

dimension consists of two factors (Table 1). The two-

factors findings of this study may confirm Amérigo et

al., (2007) which argue that ecocentrism seems to

include two concepts: the self in nature

(egobiocentrism) and nature itself (biospherism). In

ecocentrism motives, on the one hand, there are items

about physical or psychological benefits for the

individual, brought about by the mere fact of being in

or thinking about nature (e.g. “Being out in nature is

a great stress reducer for me”). These are related to

the positive emotional effects produced by contact

with nature where the protagonist is the self and it is

the only direct beneficiary of the goodness of the

natural environment which could be considered to be

related to an egoistic dimension (Amérigo et al.,

2007). On the other hand, the remaining ecocentric

items refer to biospheric aspects that emphasize the

intrinsic value of Nature (e.g. “Nature is valuable for

its own sake”) which may be oriented to two different

viewpoints of (a) a psychosocial perspective that

contemplates the human-being-in-nature and in

which the environment is valued as an element that

procures the individual’s physical and psychological

well- being, and (b) a strictly biospheric dimension in

which the environment is valued intrinsically and that

contemplates the nonhuman elements of nature

(Amérigo et al., 2007). The present study addresses

item 2, 12, 15, and 26 as those from the

egobiocentrism factor while the remaining are those

closely related to biospherism factor.

The second measures anthropocentric motive

where the natural environment is valued due to its

importance in maintaining or enhancing the quality of

life for humankind and therefore should be protected

(Thompson & Barton, 1994, p.149). The type of issue

statement being asked are, for example, ‘the most

important reason for conservation is human survival,’

The Role of Religious Orientation and Ethical Ideologies in Environmental Concerns amongst Teachers and School Staff in East Java,

Indonesia

557

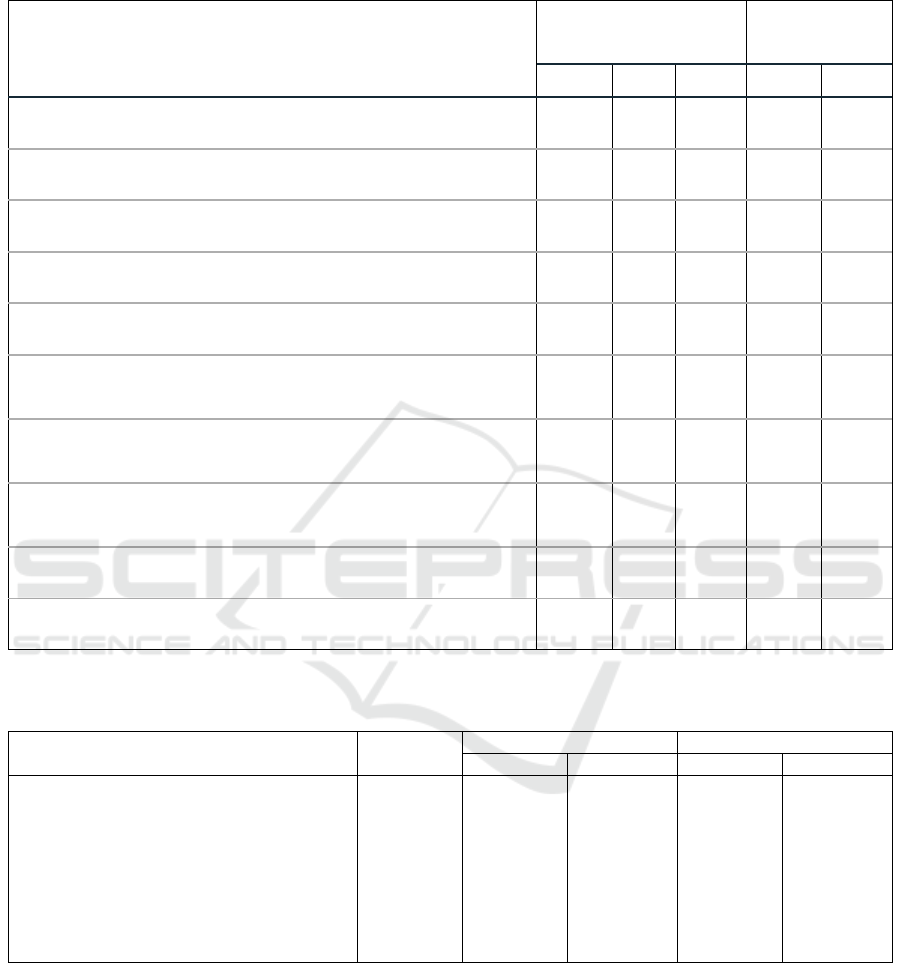

Table 3: EASEA-general environment apathy rotated factor matrix.

Items

Model 1 (using

eigen value > 1)

Model 2 (as one

factor)

1 2

ECCANTH03 Environmental threats such as deforestation and ozone

depletion have been exaggerate

d

.462

.518

ECCANTH07 It seems to me that most conservationists are pessimistic and

somewhat

p

aranoid.

.535

.594

ECCANTH09 I do not think the problem of depletion of natural resources

is as as bad as man

y

p

eo

p

le make it out to be

.692

.651

ECCANTH10 I find it hard to get too concerned about environmental

issues

.721

.611

ECCANTH14 I do not feel that humans are dependent on nature to survive .445 .545

ECCANTH17 I don't care about environmental problems .746 .549

ECCANTH18 I'm opposed to programs to preserve wilderness, reduce

p

ollution and conserve resources

.683 .591

Extraction Method: Principal Axis Factoring. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization.

‘we need to preserve resources to maintain a high

quality of life,’ or ‘one of the best things about

recycling is that it saves money.’ There are total of 10

questions in the anthropocentric motive dimension.

However, after principal axis factoring factor

analysis, this study not only reduced the items to only

seven items, but also found that the anthropocentric

motives dimension consisted of two factors (Table 2).

The outcome of two-factors anthropocentric motives

are unexpected considering that item 5 was not an

original item rather than a new one created in order to

give a clear, simple to understand Indonesia

translation of item 4. We assumed that the second

factor (consisted of only item 4 and 5) might emerge

because of the similarity of the statement and the

order of appearance next to each other in the

questionnaire. This may give involuntary needs for

consistency to the participants when answering item

5 after they finish answering the previous one (item

4). After reliability analysis, this study decided to use

Model 2 anthropocentric scale using only 6 items

(5,20,22,25,27,29).

Lastly, the third-dimension measures general

apathy to the natural environment. The type of issue

statement being asked are, for example,

‘environmental threats such as deforestation and

ozone depletion have been exaggerated,’ too much

emphasis has been placed on conservation,’ or ‘I don't

care about environmental problems.’ There are total

of nine questions in the anthropocentric motive

dimension. However, after principal axis factoring

factor analysis, this study not only reduced the items

to only seven items, but also found that the apathy

dimension consisted of two factors instead of one.

However, after ensuring a relatively stable Cronbach

alpha’s reliability in one factor model, the present

study decided to retain the environmental apathy

dimension as it was originally, a one factor construct

(model two, see Table 3).

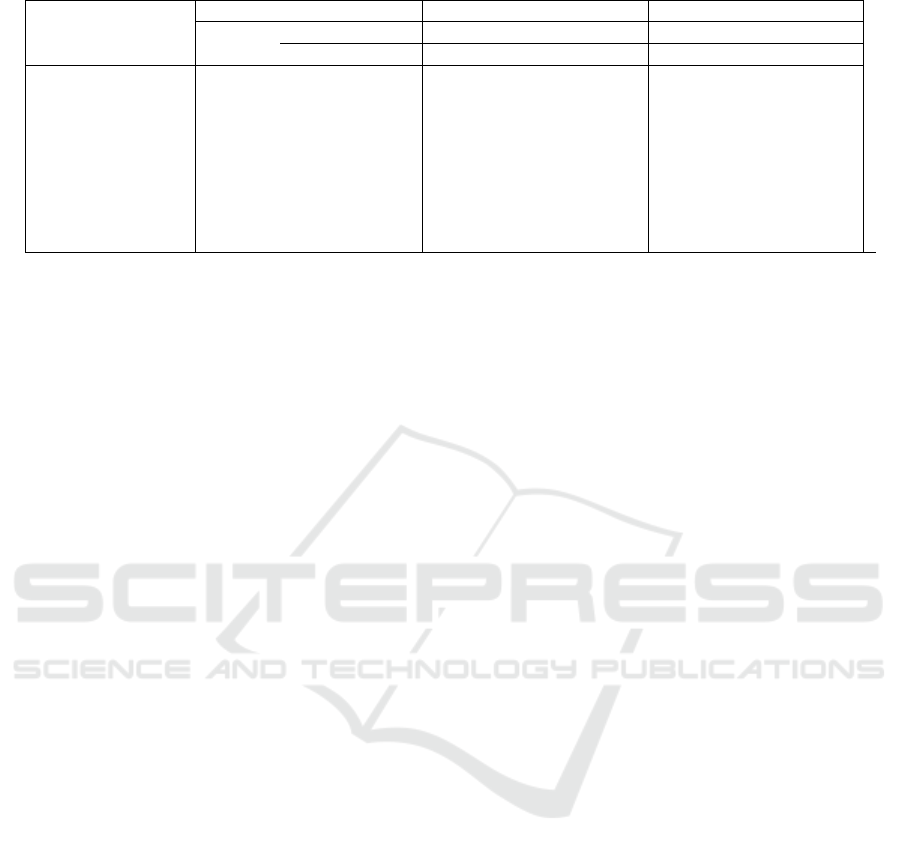

In the third section, the Religious Orientation

Scale (ROS) (Allport, 1966; Allport & Ross, 1967;

Leong & Zachar, 1990) was originally used to

measure intrinsic and extrinsic religious orientation.

We used Maltby's (1999) 15-item version which

incorporated Kirkpatrick's (1999) analysis expanding

ROS into three scales: intrinsic orientation (IP),

extrinsic personal—religion as a source of comfort

(EP) and extrinsic social—religion as social gain

(ES). The 15-item scale therefore consists of nine

questions addressing IP, for example, ’I try hard to

live all my life according to my religious beliefs’,

’My whole approach to life is based on my religion’,

’It is important to me to spend time in private thought

and prayer’); three questions addressing EP, for

example ‘Prayer is for peace and happiness’, ‘I pray

mainly to gain relief and protection’; and lastly, the

remaining three covering the ES dimension, for

example, ‘I go to church because it helps me make

friends’, ‘I go to church mainly because I enjoy

seeing people I know there’. However, after principal

axis factoring factor analysis, the present study found

only two dimensions of intrinsic personal (IP) and

extrinsic social (ES). After factor analysis, the EP was

accounted as the same factor as IP (Table 4), and thus,

will be considered as the same as IP.

In the fourth section, the Ethical Position

Questionnaire (EPQ) was used to measure the

differences in personal moral philosophy (Forsyth,

1980; Galvin & Herzog, 1992). The original EPQ was

a 20-items Likert scale consist of two sub-scales.

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

558

Table 4: ROS rotated factor matrix

Items

Facto

r

1 2

ROS01

(

IP

)

I tr

y

hard to live all m

y

life accordin

g

to m

y

reli

g

ious beliefs .673

ROS03 (IP) I have often had a strong sense of God’s presence .608

ROS04 (IP) My whole approach to life is based on my religion .705

ROS05 (IP) Prayers I say when I’m alone are as important as those I say in church .577

ROS06

(

IP

)

I attend church once a week or more .358

ROS07

(

IP

)

M

y

reli

g

ion is im

p

ortant because it answers man

y

q

uestions about the meanin

g

of life .741

ROS08

(

IP

)

I en

j

o

y

readin

g

about m

y

reli

g

ion .750

ROS09 (IP) It is important to me to spend time in private thought and

p

raye

r

.630

ROS10 (EP) What religion offers me most is comfort in times of trouble and sorrow .665

ROS11 (EP) Prayer is for peace and happiness .764

ROS12 (EP) I pray mainly to gain relief and protection .622

ROS13

(

ES

)

I

g

o to church

b

ecause it hel

p

s me make friends .833

ROS14

(

ES

)

I

g

o to church mainl

y

because I en

j

o

y

seein

g

p

eo

p

le I know there .894

ROS15

(

ES

)

I

g

o to church mostl

y

to s

p

end time with m

y

friends .787

Extraction Method: Principal Axis Factoring. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization.

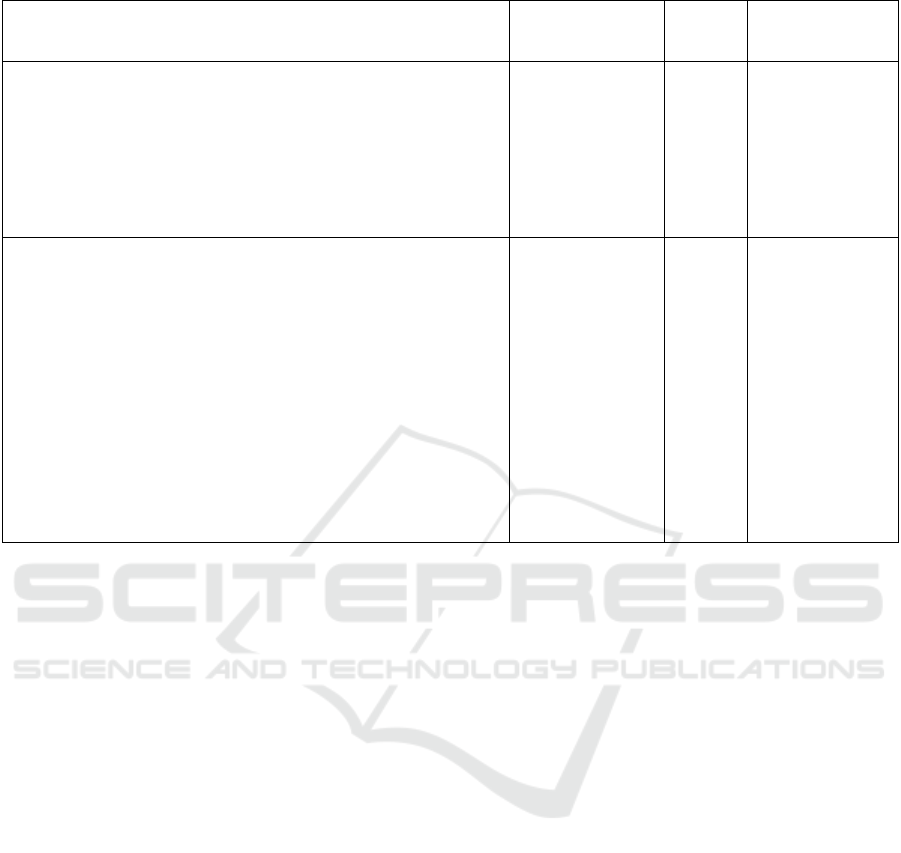

The first 10 items were designed to measure the

ethical idealism dimension, while the last 10 items

measured ethical relativism. Respondents were asked

to respond to statement using the nine-point EPQ

ranging from one (completely disagree) to nine

(completely agree). Regarding the ethical idealism,

six items were removed from analysis of this study.

Four out of those six items were removed because of

significant skew values which were outside the range

between -2 to 2 (Kim, 2013). The remaining two were

removed because of low factor loading, along with

three items from ethical relativism. After principal

axis factoring factor analysis, the present study uses

only 11 EPQ items. In which four items from the

idealism scale, and seven items from the relativism

scale. Factor analysis also found that the remaining

seven items of ethical relativism were put into two

factors. However, after ensuring a relatively stable

Cronbach alpha’s reliability in one factor model, the

present study decided to retain ethical relativism as it

was, a one factor construct (model two, see Table 5).

Statistical analysis

Religious orientation, ethical ideologies and

EASEA were analysed with IBM SPSS 24 using

multiple regression statistical procedures. This study

also used Pearson correlation product moment in

investigating the relation between religious

orientation and ethical ideologies. The resulting

correlation tables provides additional explanation for

the multiple regression results.

One common method examining EPQ were

conducted using ANOVA design (B Su & Martens,

2017; Bingtao Su & Martens, 2018), where EPQ was

considered as categorical variables differentiated into

four groups depending on the high and low of each

ethical idealism and relativism score. These groups

are, situationists (high idealism and high relativism),

subjectivists (low idealism and high relativism),

absolutists (high idealism and low relativism) and

exceptionists (low idealism and low relativism)

(Figure 1). In this study however, we view that it is

best to retain the interval properties from the total

score of ethical idealism and relativism to provide

richer and a more detailed data. Thus, multiple

regression is our selected statistical procedure for the

given data.

Figure 1: Ethical positions according idealism and

relativism.

This study uses two models of multiple

regression. The first model only investigates the main

variables, while the second model takes all main

variables with the demographic and other important

determinants. For both of the regression models, this

The Role of Religious Orientation and Ethical Ideologies in Environmental Concerns amongst Teachers and School Staff in East Java,

Indonesia

559

Table 5: EPQ pattern matrix.

Model 1 (using eigen

value > 1)

Model 2 (forced

as 2 factor

loadin

g

s

)

1 2 3 1 2

EPQ02 (I) Risks to another should never be tolerated, irrespective of

how small the risks might be.

.551

.549

EPQ03 (I) The existence of potential harm to others is always wrong,

irrespective of the benefits to be gained.

.651

.656

EPQ08 (I) The dignity and welfare of the people should be the most

important concern in any society.

.581

.580

EPQ10 (I) Moral behaviors are actions that closely match ideals of

the most “perfect” action.

.465

.463

EPQ15 (R) Questions of what is ethical for everyone can never be

resolved since what is moral or immoral is up to the individual.

.650

.603

EPQ16 (R) Moral standards are simply personal rules that indicate

how a person should behave and are not be be applied in making

judgments of others.

.704

.589

EPQ17 (R) Ethical considerations in interpersonal relations are so

complex that individuals should be allowed to formulate their own

individual codes.

.712

.742

EPQ18 (R) Rigidly codifying an ethical position that prevents certain

types of actions could stand in the way of better human relations and

adjustment.

.425

.561

EPQ19 (R) No rule concerning lying can be formulated; whether a lie

is permissible or not permissible totally depends upon the situation.

.762

.673

EPQ20 (R) Whether a lie is judged to be moral or immoral depends

upon the circumstances surrounding the action.

.748

.600

Extraction Method: Principal Axis Factoring. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization.

Table 6: Skewness and kurtosis value of main variables.

N Skewness Kurtosis

Statistic Statistic Std. Erro

r

Statistic Std. Erro

r

EASEA-Ecocentric E

g

obios

p

her

(

EEM

)

929 -.422 .080 .556 .160

EASEA-Ecocentric Biosphere (EBM) 929 -.469 .080 .876 .160

EASEA-Anthro

p

ocentric Motives

(

AM

)

929 -.505 .080 1.298 .160

EASEA-General environment Apathy (GEA) 929 .343 .080 -.119 .160

EPQ Idealis

m

929 -1.196 .080 1.162 .160

EPQ Relativis

m

929 -.568 .080 -.017 .160

ROS Intrinsic Personal 929 -.751 .080 1.430 .160

ROS_Extrinsic Social 929 .195 .080 -.495 .160

Valid N

(

listwise

)

929

study avoids stepwise method in considering that

stepwise estimates are not invariant to

inconsequential linear transformation (Smith,

2018)Rather, we follow Whittingham et al.

(2006)suggestion to use a full model including all of

the effects (enter method) for the second regression

model, where it takes all multiple variables (main

variables, demographic and other determinants)

which mainly consist of either interval or categorical

properties. As a side note, this study converts all

categorical variables into dummy variables, in which

we expand each category as a new variable scored

with either one or zero.

As Pearson correlation procedure is vulnerable

from skewed and kurtosis distribution, we made

preliminary normal distribution check to avoid

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

560

inflated correlation. Each item in the questionnaire

were checked for normal distribution assumption. In

regards to normal distribution assumption, Kim

(2013) stressed that the tendency of large samples

producing inflated z in consideration to large samples

will usually produce a very small standard error for

both skewness and kurtosis. Therefore, using

skewness and kurtosis reference values for N more

than 300, the present study removed items with

kurtosis value outside the range between -7 to 7, or

skew value outside the range between -2 to 2 (Kim,

2013). After analyzing each items in the

questionnaires, this study removed four items from

EPQ idealism, which were “People should make

certain that their actions never intentionally harm

another even to a small degree”, “One should never

psychologically or physically harm another person”,

“One should not perform an action which might in

any way threaten the dignity and welfare of another

individual”, and “If an action could harm an innocent

other, then it should not be done”. Table 6 shows that

all scales from the collected data is safely within the

normal distribution bound. Thus, no transformation

for normalization is needed.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Instrument Validity

Table 7 provides the descriptive statistics for the

variables used in the analysis. All the Cronbach’s

coefficient are acceptable, ranging from a moderate

internal consistency value of 0.66 for the ‘EPQ

Idealism’ issue to a value of 0.88 for the intrinsic

personal religious orientation.

The mean score for IP was 4.22 (SD=0.53, with

maximum score of five) indicating that, overall, the

respondents considered themselves to be strongly

committed to their personal religious life. The mean

score for ES was 2.79 (SD=0.99) indicating that

overall respondents were neither strongly nor weakly

disposed towards viewing their religious practices as

an instrument for social gain.

The mean idealism score of 7.2 (SD= 1.22, with a

maximum score of 9) indicated that, in general, the

sample had a strong idealistic ethical ideology, where

they believe that their ethical behaviour will always

lead to positive consequences. The mean relativism

score was 6.29 (SD=1.46), indicating that on the

whole, the respondents believe that moral decision-

making should be situational, rather than based on

universal principles.

The ecocentric for egobiosphere values mean

score was 3.9 (SD = 0.64, maximum score of five),

indicating that as a whole, the respondents had rather

high belief in valuing the importance of the natural

environment for one’s own positive emotional effect.

The ecocentric for biosphere values mean score was

3.67 (SD = 0.66), indicating that as a whole, the

respondents had an above average belief in valuing

the importance of the natural environment. The

anthropocentric motive mean score was 3.87 (SD =

0.54) indicating that the respondents had an above

average belief in valuing the natural environment

importance for the benefit of human. Lastly, the

general environmental apathy mean score was 2.52

(SD = 0.72), indicating that the respondents had

neither strong nor weak apathy to the natural

environment.

Table 7: Descriptive statistics and measurement characteristics for variables.

Variable Scale description

Number of

items

Reliability Mean SD

ROS-Intrinsic Personal (IP) 5-point Likert-like 11 0.88 4.22 0.53

ROS-Extrinsic social (ES) 5-point Likert-like 3 0.87 2.79 0.99

EPQ Idealism 9-point Likert-like 4 0.66 7.2 1.22

EPQ Relativism 9-point Likert-like 7 0.80 6.29 1.46

Ecocentric Egobiosphere

(EEM)

5-point Likert-like 4 0.71 3.90 0.64

Ecocentric Biosphere (EBM) 5-point Likert-like 3 0.74 3.67 0.66

Anthropocentric Motives (AM) 5-point Likert-like 5 0.66 3.87 0.54

Env. Apathy 5-point Likert-like 7 0.79 2.52 0.72

*Using pearson correlation coefficient instead of Cronbach alpha, considering that the scale consists of only two items.

The Role of Religious Orientation and Ethical Ideologies in Environmental Concerns amongst Teachers and School Staff in East Java,

Indonesia

561

Table 8: Multiple regression towards egobiosphere value in ecocentric motive (EEM).

Model

EEM

b (Std. b)

Effect

Size

95% CI

Lower Upper

1 - Main Variable

A

(R=0.33; R

2

=0.11, df=9,439)

(Constant) 1.70 ** 1.330 2.077

EPQ Ideal 0.00 0.01 0.00

C

-0.029 0.039

EPQ Relative 0.04 0.11 ** 0.01

C

0.018 0.070

IP 0.43 0.35 ** 0.13

C

+ 0.351 0.499

ES 0.04 0.06 0.00

C

-0.003 0.076

2 - Main Variable + Demographic and other determinants

B

(R=0.40; R

2

=0.16, df=40, 408)

(Constant) 2.62 **

1.949 3.294

IP 0.34 0.28 ** 0.07

C

+ 0.243 0.434

How often do you visit a zoo or aquarium

1

? Once a year:

Yes (1) – No (0)

0.18 0.13 * 0.26

D

+ 0.043 0.291

How often do you visit a zoo or aquarium

1

? Once every six month:

Yes (1) – No (0)

0.22 0.10 * 0.36

D

+ 0.056 0.396

How often do you consume meat in a week

2

? I don't consume meat:

Yes (1) – No (0)

-0.23 -0.09 * 0.11

D

-0.249 0.115

What is your gender? Female

3

:

Yes (1) – No (0)

0.10 0.08 * 0.16

D

0.022 0.187

*p<.05; **p<.01;

A

regression using enter method in a stepwise manner;

B

regression using enter method, unsignificant results

omitted;

C

effect-size calculation using eta squared (F

2

);

D

effect-size calculation using Hedge’s g; +small effect size F

2

>=0.02

(or in some cases of categorical dummy variable, using Cohen’s D/Hedges’g >= 0.2); ++medium effect size F

2

>=0.15 (or in

some cases of categorical dummy variable, using cohen’s D/Hedges’g >=0.5);

1

compared to respondents who never visit

public zoo/aquarium;

2

compared to respondents who eat meat once a week;

3

compared to male respondent.

3.2 Response Rates

From 1007 total responses obtained, 78 respondents

(8%) were removed due to unengaged answers (in

other words, these were the respondents who gave the

same answer for all the questions in the

questionnaire). After the removal, there were still

some incomplete answers (listwise missing case)

from for the remaining 929 participants. Those

missing cases were imputed using a linear trend

method. In total, this research collected and analysed

929 respondents. The mean age of all respondents

(51% female (N=475) and 49% male (N=454)) is

36.38 years old (SD=10.02). The completed surveys

have a relatively balanced proportion of rural (61%)

and urban (39%) areas. Additionally, several

complementary variables were assessed, such as pet

ownership, where 48% of respondents adopted one or

more pet(s), while 52% of respondents didn’t adopt

any pet. For home ownership, 1% lived in apartment,

9% live in a rented room, 55% lived and owned a

house, while the remaining 40% still live in their

parent’s house. For the highest level of education,

74% hold a Bachelor, 14% a PhD or a Master, 8%

graduated high school, 3% hold a diploma, while for

the categories of those who either finished middle or

high school, where they either hold another degree, or

did not answer, were each less than 1%. Regarding

the frequency of zoo or aquarium visitation, 4%

visited a zoo once a month, 7% at least every six

months, 22% once a year, 42% once in every two or

more years, and lastly, 22% never visited a zoo or

aquarium, leaving the remaining 1% respondents

without answer. Regarding professions, all of the

respondents were teachers or school staff. However,

some of the respondents had a secondary profession,

as follows: 5% as an entrepreneur, 39% as an

employee in the private sector, 24% as civil servants,

5% are also scholarship students, 19% are teachers or

lecturers without a secondary profession, while the

remaining 6% are either semi-retired, social workers,

or university researchers, working in the farming or

livestock sector; others did not disclose their

professions, or did not or did not want to answer.

Finally, we also asked about the frequency of weekly

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

562

Table 9: Multiple regression towards biosphere value in ecocentric motive (EBM).

Model

EBM

b (Std. b)

Effect

Size

95% CI

Lower U

pp

er

1 - Main Variable

A

(R=0.33; R

2

=0.11, df=9,439)

(Constant) 1.23 ** 0.857 1.606

EPQ Ideal 0.03 0.06 0.00

C

-0.002 0.066

EPQ Relative 0.00 -0.01 0.00

C

-0.028 0.023

IP 0.48 0.39 ** 0.17

C

+ 0.410 0.559

ES 0.06 0.10 ** 0.01

C

0.024 0.103

2 - Main Variable + Demographic and other determinants

B

(R=0.40; R

2

=0.16, df=40, 408)

(

Constant

)

1.61**

0.907 2.304

IP 0.48 0.38 ** 0.14

C

+ 0.385 0.583

What is the highest level of schooling you have completed

1

?

Senior high: Yes (1)

–

No (0)

-0.26 -0.11 * 0.49

D

++ -0.509 -0.137

*p<.05; **p<.01;

A

regression using enter method in a stepwise manner;

B

regression using enter method, unsignificant results

omitted;

C

effect-size calculation using eta squared (F

2

);

D

effect-size calculation using Hedge’s g; +small effect size F

2

>=0.02

(or in some cases of categorical dummy variable, using Cohen’s D/Hedges’g >= 0.2); ++medium effect size F

2

>=0.15 (or in

some cases of categorical dummy variable, using cohen’s D/Hedges’g >=0.5);

1

compared to those respondent with

Master/PhD degree.

meat consumption whereby 6% didn’t eat meat, 28%

ate meat once in a week, 36% ate meat two to three

days in a week, 13% four to six days in a week, and

lastly, 14% ate meat every day.

3.3 Ethical Ideologies, Religious

Orientation and the Attitude

towards Natural Environment

Preservation

There are two models developed and analysed using

the multiple regression method. The first model

analyses the four main variables relation (EPQ

Idealism, relativism, intrinsic personal and extrinsic

social religious orientation) to the natural

environment protection attitude, while the second

model investigates all four main variables with all

potential demographic and other determinants taking

together as well as independently. In both of the

model, we regress all the predictors to environmental

concerns variables which are ecocentric egobiosphere

(EEM, Table 8), ecocentric biosphere (EBM, Table

9), anthropocentric motive (AM, Table 10) and

general environment apathy (GEA, Table 11).

For EEM (Table 8) the first model shows that

higher EEM score relates to a higher relativism

(b=0.04, p<0.01) and a higher IP (b=0.43, p<0.01).

However in the second model, EEM score is more

likely relate to IP (b=0.34, p<0.01), public zoo or

aquarium visitation (once a year b=0.18, p<0.01 and

once every semester b=0.22, p<0.01), gender

(b=0.10, p<0.01) and meat consumption (b=-0.23,

p<0.01).

For EBM (Table 9) the first model shows that

higher EBM score relates to a higher IP (b=0.48,

p<0.01) and a higher ES (b=0.06, p<0.01). However

in the second model, EBM score is more likely relate

to IP (b=0.48, p<0.01) and level of schooling (b=-

0.26, p<0.01).

For AM (Table 10) the first model shows that

higher EEM score relates to a higher relativism

(b=0.04, p<0.01) and a higher IP (b=0.46, p<0.01).

These relationships are replicated also in the second

model, whereby EEM score is more likely relate to a

higher relativism (b=0.04, p<0.01), a higher IP

(b=0.46, p<0.01) and older age (b=0.01, p<0.05).

However lower EEM is more likely occurred in

bachelor level of schooling compared to those of

Master/PhD (b=-0.12, p<0.05).

For GEA (Table 11), higher GEA score relates to

a lower idealism (b=-0.07, p<0.01), a higher R

(b=0.1, p<0.01), a lower IP (b=-0.25, p<0.01), and a

higher ES (b=0.17, p<0.01). However in the second

model, GEA score is more likely relate to a higher

relativism (b=0.1, p<0.01), lower IP (b=-0.26,

p<0.01), higher ES (b=0.12, p<0.01) and lower

idealism (b=-0.05, p<0.05) and level of schooling

(b=-0.26, p<0.01) along with meat consumption (four

to six day weekly (b=-0.21, p<0.05) and no meat

consumption(b=0.21, p<0.05)), household expenses

(b=0.16, p<0.05), and religious organization

affiliation (b=0.13,

p<0.05).

The Role of Religious Orientation and Ethical Ideologies in Environmental Concerns amongst Teachers and School Staff in East Java,

Indonesia

563

Table 10: Multiple regression towards anthropocentric motive (AM).

Model

AM

b (Std. b)

Effect

Size

95% CI

Lower U

pp

er

1 - Main Variable

A

(R=0.33; R

2

=0.11, df=9,439)

(

Constant

)

1.48 ** 1.183 1.783

EPQ Ideal 0.01 0.03 0.00

C

-0.014 0.040

EPQ Relative 0.04 0.12 ** 0.01

C

0.020 0.061

IP 0.46 0.45 ** 0.24

C

+ 0.404 0.524

ES 0.03 0.05 0.00

C

-0.002 0.061

2 - Main Variable + Demographic and other determinants

B

(R=0.40; R

2

=0.16, df=40, 408)

(

Constant

)

1.60**

1.053 2.147

IP 0.46 0.44 ** 0.20

C

+ 0.378 0.533

EPQ Relative 0.04 0.12 ** 0.01

C

0.015 0.063

What is

y

our a

g

e? 0.01 0.11 * 0.01

C

0.001 0.011

What is the highest level of schooling you have completed?

Bachelor: Yes (1)

–

No (0)

-0.12 -0.10 * 0.26

D

+ -0.243 -0.037

*p<.05; **p<.01;

A

regression using enter method in a stepwise manner;

B

regression using enter method, unsignificant results

omitted;

C

effect-size calculation using eta squared (F

2

);

D

effect-size calculation using Hedge’s g; +small effect size F

2

>=0.02

(or in some cases of categorical dummy variable, using Cohen’s D/Hedges’g >= 0.2); ++medium effect size F

2

>=0.15 (or in

some cases of categorical dummy variable, using cohen’s D/Hedges’g >=0.5);

1

compared to those respondent with

Master/PhD degree.

Table 11: Multiple regression towards general environmental apathy (GEA).

Model

GEA

b (Std. b)

Effect

Size

95% CI

Lower Upper

1 - Main Variable

A

(R=0.33; R

2

=0.11, df=9,439)

(

Constant

)

2.97 ** 2.552 3.380

EPQ Ideal -0.07 -0.11 ** 0.01

C

-0.104 -0.029

EPQ Relative 0.10 0.23 ** 0.05

C

+ 0.074 0.131

IP -0.25 -0.19 ** 0.03

C

+ -0.335 -0.171

ES 0.17 0.24 ** 0.06

C

+ 0.128 0.215

2 - Main Variable + Demographic and other determinants

B

(R=0.40; R

2

=0.16, df=40, 408)

(

Constant

)

2.91 ** 2.174 3.648

EPQ Relative 0.10 0.23 ** 0.05

C

+ 0.065 0.131

IP -0.26 -0.19 ** 0.03

C

+ -0.363 -0.155

ES 0.12 0.17 ** 0.03

C

+ 0.068 0.174

How often do you consume meat in a week

1

? Four to six days a

week: Yes

(

1

)

–

No

(

0

)

-0.21 -0.10 * 0.19

D

+ -0.016 0.283

What is your gross household expenses per month

2

? Refuse to

answer: Yes

(

1

)

–

No

(

0

)

0.16 0.10 * 0.17

D

-0.226 -0.007

EPQ Ideal -0.05 -0.09 * 0.01

C

-0.097 -0.008

Do you have any affiliation to religious organization

3

? Yes (1) –

No (0)

0.13 0.09 * 0.10

D

-0.022 0.169

How often do you consume meat in a week

1

? I don't consume

meat: Yes (1)

–

No (0)

0.25 0.09 * 0.20

D

+ -0.336 0.057

*p<.05; **p<.01;

A

regression using enter method in a stepwise manner;

B

regression using enter method, unsignificant results

omitted;

C

effect-size calculation using eta squared (F

2

);

D

effect-size calculation using Hedge’s g; +small effect size F

2

>=0.02

(or in some cases of categorical dummy variable, using Cohen’s D/Hedges’g >= 0.2); ++medium effect size F

2

>=0.15 (or in

some cases of categorical dummy variable, using cohen’s D/Hedges’g >=0.5);

1

compared to respondents who eat meat once

a week;

2

compared to respondent whose monthly expenses below IDR 5 million;

3

compared to those respondent who don’t

have affiliation/membership to any religious organization.

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

564

In summary, there are no evidence to support the

hypothesized relationship direction for EEM, EBM

and AM. ES is not significant with both EEM and

AM, while relativism is not significant to EBM. High

scorer of IP, however, will likely relates to a higher

EEM, EBM and AM. The higher the intrinsic

religious orientation, the more a person believes in the

importance for preserving the natural environment, in

both ecocentric and anthropocentric motives. In

addition, relativism and ES only relate to

anthropocentric motives. The higher the relativism

and extrinsic social religious orientation, the more

likely a person believes in anthropocentric values as

the motivation for preserving the natural

environment. For the second model, only in GEA that

all the main variables show consistent and stable

relationship. Higher GEA score is more likely scored

when a person scores a lower idealism, a lower

intrinsic personal religious orientation, a higher

relativism and a higher extrinsic social religious

orientation.

3.4 Extrinsic Social Religious

Orientation, Ethical Ideologies, and

Environmental Concerns

The hypothesis presented in this section is that a

higher ES correlates to lower idealism, higher

relativism, and a higher general environmental

apathy. We find only partial support for the fourth and

fifth hypothesis. The results show partial support to

the fourth hypothesis. On the one hand, to both

idealism and relativism as we found no support for

the relation of IP we also found no support in ES. It

seems that ES only positively correlates with

relativism (r[927]=0.15, p<0.01), and IP only

positively correlates with idealism (r[927]=0.21,

p<0.01). The relation of religious orientation to

environmental concerns is very similar with ethical

ideologies. The only difference is, while there is

correlation between idealism and relativism

(r[927]=0.35, p<0.01), we find no correlation

between IP and ES (Table 12).

Moreover, in Table

11, using multiple regression we confirm that higher

extrinsic social religious orientation relates to a

higher GEA in both the first and the second model.

This means that when holding all other variables

constant, one point increase in ES is more likely to

increase 0.17 point of GEA score in the first, and 0.12

point in the second model. In both models, the effect-

size of ES shows small effect-size (0.02 <= F2 <

0.15). For the confidence interval, if we were to re-fit

both models for total of 20 random trials, taking

samples of the same size from the same population,

we can be confident that for 19 out of total 20 trials

(95% of the time), an increase of one unit of ES will

be more likely to increase GEA between 0.128 to

0.215 point in the first model, while in the second

model will be more likely to increase GEA between

0.068 to 0.174 point. Therefore, except for with

idealism, the present study accepts all the expected

ES’ relations in the hypothesis.

3.5 Ethical Ideologies and Religious

Orientation

The working hypothesis presented in this section is

that higher personal religious orientation relates to a

higher idealism and a lower relativism. Table 12

provides the correlation matrix for the studied

variables. We find positive relationship between

idealism with personal religious orientation (IP)

(r[927]=0.21, p<0.01). However, there is no

significant relationship between relativism with IP

(r[927]=0.000, p>0.05), and therefore, while the

hypothesis is rejected by every relation with

relativism, it is accepted in predicting the relationship

between idealism with IP. Lastly, the correlation

between extrinsic social religious orientation and

idealism (r[927]=-0.02, p>0.05) and relativism

(r[927]=0.15, p<0.01) is already reported with a more

detail in previous section (section 3.4).

Table 12: Correlation Matrix between ROS and EPQ.

IP ES EPQ Idealism

r

CI 95%

r

CI 95%

r

CI 95%

lower upper lower upper lower upper

IP

ES 0.05 -0.02 0.11

Idealism 0.21

**

0.15 0.27 -0.02 -0.08 0.05

Relativism 0.00 -0.06 0.06 0.15

**

0.08 0.21 0.35

**

0.29 0.41

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

The Role of Religious Orientation and Ethical Ideologies in Environmental Concerns amongst Teachers and School Staff in East Java,

Indonesia

565

Table 13: Correlation Matrix between EASEA components.

EEM EBM AM

r

CI 95%

r

CI 95%

r

CI 95%

lowe

r

u

pp

e

r

lowe

r

u

pp

e

r

lowe

r

u

pp

e

r

Eco Egobiosphere

(

EEM

)

Eco Biosphere

(

EBM

)

0.437

**

0.384 0.488

Anthropocentric

motivation

(

AM

)

0.454

**

0.401 0.504 0.497

**

0.447 0.544

General

Environment

Apathy (GEA)

-0.113

**

-0.176 -0.049 -0.102

**

-0.165 -0.038 -0.041 -0.105 0.023

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

3.6 Natural Environment Preservation

Attitude (Ease)

The working hypothesis presented in this section is

general environmental apathy scale will negatively

correlated with ecocentric and anthropocentric

motives. Table 13 provides the correlation matrix for

the studied variables. We find significant correlation

in the predicted direction between general

environment apathy (GEA) with ecocentric

egobiosphere motive (EEM) (r[927]=-0.11, p<0.01),

and with ecocentric biosphere motives (EBM)

(r[927]=-0.1, p<0.01). However, there is no

significant relationship between GEA with

anthropocentric motives (AM) (r[927]=-0.04,

p<0.05).

3.7 Demographic and Other

Determinants

For all the second regression model (see Table 8 to

Table 11), aside the main variables, there are some

demographic and other determinants closely related

to environmental concerns (EEM, EBM, AM and

GEA which are gender, age, level of schooling,

weekly meat consumption, zoo visitation, monthly

expenses, and affiliation to religious organization.

While these determinants found significantly related

with environmental preservation concerns, this study