Using of Resource Sources of Interactive Semantic Networks in Offline

Translator Training

Rostyslav O. Tarasenko

1 a

, Svitlana M. Amelina

1 b

, Serhiy O. Semerikov

2,3,4 c

and Vasyl D. Shynkaruk

1 d

1

National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine, 15 Heroiv Oborony Str., Kyiv, 03041,Ukraine

2

Kryvyi Rih State Pedagogical University, 54 Gagarin Ave., Kryvyi Rih, 50086, Ukraine

3

Kryvyi Rih National University, 11 Vitalii Matusevych Str., Kryvyi Rih, 50027, Ukraine

4

Institute for Digitalisation of Education of the NAES of Ukraine, 9 M. Berlynskoho Str., Kyiv, 04060, Ukraine

Keywords:

Interactive Semantic Network, Terminology Resources, Terminology Databases, Autonomous Learning,

Translator.

Abstract:

The article focuses on the use of resource sources of interactive semantic networks in translator training, partic-

ularly during offline and autonomous learning due to lockdown and martial law situations. The most common

external terminology resources associated with interactive semantic networks are identified. The technology

of selection and structuring of specialised terminology on the basis of interactive semantic networks for their

further use in the study of foreign languages and mastering automated translation systems has been developed

and proposed. The criteria for creating and supplementing terminological databases with appropriate struc-

turing of the domain terminology selected on the basis of interactive semantic networks have been defined,

namely universality, structurability, convertibility, extensibility. The possibility of further use of terminology

bases for foreign language learning using mobile applications, mastering Computer Aided Translation (CAT)

systems, mastering Computer Aided Interpretation (CAI) are outlined. Based on the experimental construc-

tion of an individual interactive semantic network based on external terminology resources, positive results

are stated and directions for further research activities to strengthen the technological training of prospective

translators are identified.

1 INTRODUCTION

In a changing world at the beginning of the 21st cen-

tury, education is also changing rapidly. Learning is

now seen as a lifelong process that is essential for

adapting to new environments, and therefore for en-

suring personal economic and social success. Such

learning implies that people have to ‘learn to learn’.

Consequently, providing students with the knowledge

and skills to enable them to manage their own educa-

tional process effectively becomes one of the aims of

higher education. During the evolution of the educa-

tion system, the issue of autonomy has become one

of the main themes of language education research,

and in the context of recent global developments (the

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6258-2921

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6008-3122

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0789-0272

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8589-4995

coronavirus pandemic, COVID-19, restrictive quaran-

tine measures and lockdowns, the transition to dis-

tance learning) it has become particularly relevant.

At the same time, the new format of the educa-

tional process puts forward new requirements regard-

ing the ways of realising learning objectives, meth-

ods of learning communication and teacher-student

interaction, means of ensuring the effectiveness of

learning subjects and achieving the programme learn-

ing outcomes envisaged in the standards and curricula

for training specialists, including translators. Both in

terms of learning activities and in terms of the future

work of translators, technological training is becom-

ing increasingly important. The present is forcing, on

the one hand, a strengthening of the technological as-

pects of university translator training and, on the other

hand, a rethinking of the organisational forms of train-

ing, the search for appropriate means, the combina-

tion of students’ independent mastering of individual

study materials with the technologicalization of the

390

Tarasenko, R., Amelina, S., Semerikov, S. and Shynkaruk, V.

Using of Resource Sources of Interactive Semantic Networks in Offline Translator Training.

DOI: 10.5220/0012064800003431

In Proceedings of the 2nd Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology (AET 2021), pages 390-405

ISBN: 978-989-758-662-0

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

educational process. Using elements of augmented

and virtual reality can meet such complex objective

requirements of the current situation.

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

An analysis of the psycho-pedagogical literature has

shown that there has recently been increased inter-

est in certain aspects of autonomous learning by both

domestic and foreign researchers in different fields

of science. Benson (Benson, 2005), noting the re-

cent increased attention to learning autonomy and

self-organised learning, including in foreign language

learning, emphasised the importance of different lev-

els of student autonomy in distance learning. Cot-

terall (Cotterall, 2000) identified five principles on

which a stand-alone language course should be based

and attributed them to learners’ goals; language learn-

ing process; theory – task, design; learners’ strate-

gies; reflection on learning. Hurd et al. (Hurd et al.,

2001) emphasise one of the main problems of auton-

omy in distance learning, which in their view is the

difficulty of selecting learning material for students

to learn independently. This decision is complicated

by two factors. On the one hand, in order to be suc-

cessful in the programme, students must develop a

number of strategies and skills that will allow them to

work individually. At the same time, the syllabus of

an academic course has a definite structure in which

the scope, pace and content of the syllabus are de-

termined by the teacher. Exploring the notion of au-

tonomy in distance language learning, scholars have

identified some of the skills that distance learners

need to achieve successful outcomes. Similar views

are held by Murphy (Murphy, 2006), who emphasizes

that the success of autonomy in distance learning de-

pends largely on the teaching materials, and demon-

strates the role of the teacher in the process of auton-

omy in the language distance-learning programme of

The Open University in the UK.

While considering the organisation of au-

tonomous language learning, scholars have also

explored the possibilities of using information tech-

nologies in this process. In highlighting the changes

in educational philosophy reflected in the theory

of language learning, Pemberton et al. (Pemberton

et al., 1996) noted the need to adapt to the rapid

changes in the areas of technology, communications,

and the labour market and to realise that the ability

to learn is now more important than knowledge. In

his view, it is advisable to take full advantage of

the opportunities for expanding educational services

that come with the development of technologies. In

this context, it should be noted that foreign scholars

and practitioners are increasingly hoping for the

integration of augmented reality elements into the

training of university programmes in philology and

translation. Indiana University, in particular, has

initiated one such project, which involves the multidi-

mensional deployment of elements of AR technology

that can meet precisely the specific needs of these

programmes in the form of individual modules: “We

plan on compiling the following learning modules

1) listening comprehension; 2) pronunciation prac-

tice; 3) animated 2D and 3D vocabulary introduction;

4) vocabulary quizzes; 5) roleplay dialogues where

students interact with an avatar and 6) videos with

cultural content, geography, and history. In contrast

to other digital technologies available at IU, such

as embedded videos in Canvas, we will be able to

bring real objects into language classrooms, such as

cultural artifacts, culinary samples, maps and other

objects, and connect them virtually to an augmented

world” (Scrivner et al., 2016).

According to Reinders (Reinders, 2006), in or-

der to provide students with easy access to learning

materials during offline foreign language learning, it

is advisable to create an appropriate e-learning en-

vironment. The main aim is to support students in

their self-directed learning by structuring self-study

by providing a recommended sequence of steps, pro-

viding students with information on learning strate-

gies and conducting electronic monitoring of stu-

dent work, with advice if necessary (Reinders, 2006;

Scharle and Szab

´

o, 2000).

Researchers whose academic work is related to

foreign language teaching point out that special atten-

tion should be paid to the development of students’ re-

sponsibility; otherwise, the learning process will not

be successful (Scharle and Szab

´

o, 2000). I. Moore

even points out that student autonomy begins with

students taking responsibility for both the process and

the results of their learning: “In doing this: They

can identify their learning goals (what they need to

learn), their learning processes (how they will learn

it), how they will evaluate and use their learning; they

have well-founded conceptions of learning, they have

a range of learning approaches and skills, they can

organize their learning, they have good information

processing skills, they are well motivated to learn”

(Moore, 2010).

Little (Little, 2002) considers it likely that in the

next few years much of the research on student auton-

omy will focus on the impact of autonomous learning,

particularly when learning a foreign language, on ev-

eryone involved – students, teachers and educational

systems in general. According to the researcher, the

Using of Resource Sources of Interactive Semantic Networks in Offline Translator Training

391

role of the teacher is to create and support a learning

environment in which students can be autonomous.

The development of their learning skills cannot be

completely separated from the learning content, since

learning how to learn a foreign language differs from

learning other courses in some important respects.

At the same time, as the above list of issues ex-

amined by scholars from various countries shows, au-

tonomous learning, in particular the learning of for-

eign languages, is associated by many with the using

information technologies and the search for new ap-

proaches, not the least of which are nowadays aug-

mented, virtual and mixed reality (Liu et al., 2017).

Yagcioglu (Yagcioglu, 2015), focusing his research

on new approaches to student autonomy in language

learning, relies on UNESCO’s declared role of infor-

mation and communication technologies in learning:

“Information and communication technology (ICT)

can complement, enrich and transform education for

the better” (UNESCO, 2022). Some academics, while

extremely appreciative of the potential of augmented

and virtual reality in learning, have expressed con-

cerns about whether the education system is ready for

the fundamental changes in the educational process

that arise from these technologies, or even their el-

ements. Ochoa (Ochoa, 2016) sees augmented and

virtual reality as a new challenge for education.

The use of terminology resources is an important

support both for training (face-to-face, remote, off-

line) and for the professional work of translators. It

should be noted that, appreciating the importance of

correct use and unification of terminology, the Euro-

pean Commission has created a specific database of

terminology tools and resources (KCI, 2022). More

recently, scholars have noted that the creation of ter-

minological resources should aim at the possibility of

using them during both human and machine transla-

tion: “In a globalised society, terminological dictio-

naries – including resources such as knowledge and

terminological databases, ontologies, wordnets, “tra-

ditional” dictionaries, etc. – should comply with both

human and machine needs” (Roche et al., 2019).

Given the importance of the factors for organis-

ing offline foreign language learning identified in the

reviewed studies (students’ motivation, choice and

access to learning material, skills and strategies for

offline learning, use of information technology, AR

technology), we consider it advisable to introduce

the use of augmented reality elements in this pro-

cess, which can provide the above aspects. In pre-

vious studies to determine the possibilities of using

AR technology in the process of learning a foreign

language, a number of advantages of using elements

of this technology have been identified: the involve-

ment of different channels of information perception,

the integrity of the representation of the studied ob-

ject, faster and better memorization of new vocabu-

lary, etc. (Tarasenko et al., 2020b). The study of a

certain section of a foreign language’s vocabulary –

domain-specific terminology – is relevant both for

specialists studying a foreign language and for trans-

lators who plan to translate the field. Therefore, con-

tinuing our research, we will focus on autonomous

learning activities using AR technology in terminol-

ogy work, which is the initial phase for several pos-

sible directions of further development of the educa-

tional process – language learning, scientific and tech-

nical translation, mastering automated translation sys-

tems (Tarasenko et al., 2020a).

The purpose of this paper is to consider the pos-

sibility of using interactive semantic networks as el-

ements of augmented reality in the process of au-

tonomous learning to improve the technological train-

ing of translators in the aspect of creating domain-

specific terminology bases for their further use in

foreign language learning and mastering automated

translation systems.

3 RESULT AND DISCUSSION

Translation education at the current stage necessarily

involves technological training of translators, which

aims to develop competencies in the use of mod-

ern tools and techniques of translation, based on the

use of information technologies. An important part

of this training is for translators to acquire skills

in working with electronic terminology resources,

such as searching, structuring, storing, using termi-

nology in computer-assisted translation (CAT) sys-

tems, computer-assisted interpreting (CAI) systems,

interactive foreign language learning systems and the

like. The search for effective technological training

for translators is becoming increasingly urgent, but is

complicated by the emergence of new tools and the

rapid growth of their number. At the same time, there

is a trend towards the increasing use of cloud services

and online resources. All this makes it necessary to

constantly update the content of the educational pro-

gramme components. One of the ways of solving this

problem could be the implementation of augmented

reality elements into the educational process. The ap-

plication of augmented reality (AR – augmented real-

ity) technology will allow students to find and obtain

the necessary information more quickly, which can

be presented in symbolic, audio, graphic or animated

form (Amelina et al., 2022). The use of such tech-

nology will be particularly effective in off-line learn-

AET 2021 - Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

392

ing, as its peculiarity is the absence of constant direct

contact with the teacher and, consequently, the pos-

sible complications of acquiring certain knowledge.

This necessitates a search for augmented reality tech-

nologies that were primarily aimed at building profes-

sional skills, particularly in the case of autonomous

learning for translators in their technological training.

3.1 Technology for Selecting and

Structuring Domain-Specific

Terminology Based on Interactive

Semantic Networks

One of the options for using augmented reality ele-

ments in the technological training of translators can

be developed by us the technology of selecting and

structuring domain-specific terminology based on in-

teractive semantic networks for their further use in

the study of foreign languages and mastering auto-

mated translation systems. A schema of this technol-

ogy based on interactive semantic networks is shown

in figure 1. This technology is designed to be used in

the learning process by undergraduate students who

have already acquired the skills of working with CAT

and CAI (Tarasenko and Amelina, 2020). In devel-

oping it, we used existing interactive semantic net-

works, which are new online services and have only

become available for use in the last few years. In par-

ticular, one such service has been developed in the

framework of the EU Terminology as a Service (TaaS)

project. The goal of the TaaS project was to provide

operational access to up-to-date terms based on the

exchange of multilingual terminology data and to cre-

ate effective mechanisms for the reuse of terminology

resources.

According to the developed technology (figure 1),

the initial step is to use interactive semantic networks

for the selection and structuring of domain terminol-

ogy, which consists in the possibility of defining a se-

mantic field within a certain domain to identify ter-

minological entities for integration in the terminolog-

ical database of the respective domain. In this case,

to initialise the algorithm for the student’s construc-

tion of his/her individual semantic network, he/she

only needs to decide on any source term that relates

to the domain with which he/she plans to work on

the basis of the created terminological base. This

term is entered into the relevant elements of the inter-

face and a hierarchical structure of the semantic field

with multi-level relationships between its elements is

formed around it by means of the search engine of the

interactive semantic network. In this way, the student

is at the outset provided with a defined set of direc-

tions, each of which opens up a separate terminology

pathway. At the same time, the system provides easy

and clear visual identification of the elements in their

hierarchical order and the different types of links be-

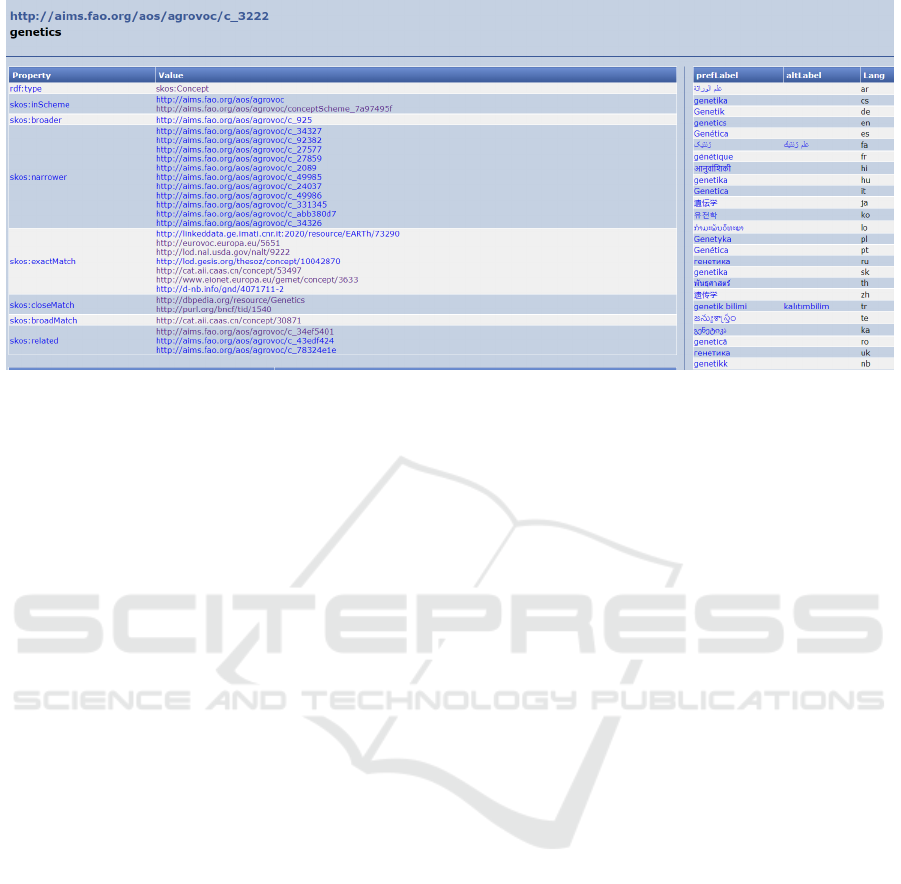

tween them. Figure 2 shows the initial phase of build-

ing a personalised interactive semantic network based

on the source term “genetics”.

Further action should be taken by the student to

develop the semantic network in one or more direc-

tions that are appropriate for his or her individual task.

The types of links between the elements of the net-

work, which indicate the hierarchical relationship be-

tween them, can help the student to decide on the

appropriate direction. In particular, the system can

automatically establish four types of such links: ex-

act, broader, narrower, related. The exact type of

link means that it is an exact match or synonymy.

In terms of moving along the development of a net-

work with such a link, the system can provide ad-

ditional opportunities to obtain search results in the

form of related terms. Using the network develop-

ment direction of the broader link, the student will be

able to further search for terms at a higher hierarchi-

cal level of concepts and move to related domains,

which will contribute to his/her understanding of the

integrity of a particular domain. A ‘narrower’ link

will allow the student to build a network in the nar-

rower direction of the field and access a list of terms

that under other circumstances he/she might have ob-

tained after a lengthy search in the relevant reference

books. This is an important aspect of using such on-

line networks, given that the translator is usually not

an expert in a particular domain and therefore cannot

have a detailed understanding of the terminological

vocabulary of that domain.

3.2 Resource Sources for

Terminological Support for

Interactive Semantic Networks

However, working with an interactive semantic web

to find relevant terms can be effective not only in the

direction of using the appropriate type of links be-

tween the network elements in a visualised mode, but

also when using a system of interactive links to rel-

evant terminology resource repositories. This can be

used if a student is interested in a specific termino-

logical element in a semantic network schema. When

it is highlighted, the system identifies and generates

a link to one so-called original site whose informa-

tion better answers the created query. In most cases,

the system identifies three main resources as original

sites:

• the Agricultural Information Management Stan-

Using of Resource Sources of Interactive Semantic Networks in Offline Translator Training

393

Figure 1: The scheme of technology for selecting and structuring domain-specific terminology based on interactive semantic

networks for further use in foreign language learning and mastering computer assisted translation systems.

Figure 2: Initial phase of creating a personalised interactive semantic network based on the source term “genetics”.

dards (AIMS) portal of the Food and Agriculture

Organization of the United Nations (FAO),

• the UNESCO Thesaurus, which is a structured list

of terms used for subject analysis and searching

AET 2021 - Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

394

Figure 3: Agricultural Information Management Standards Portal (AIMS) page.

for documents and publications in the fields of

education, culture, natural, social and human sci-

ences, communication and information,

• the classification system of international standard

nomenclature for the fields of science and tech-

nology.

It is important to note that all of these resources

support a specific model of knowledge organisation

for the World Wide Web, the so-called Simple Knowl-

edge Organisation System (SKOS). This knowledge

organisation system greatly facilitates interoperability

between different information systems by standardis-

ing thesauri, classification systems, taxonomies and

subject header systems.

The approaches to the use of these resources dif-

fer significantly. In particular, the peculiarity of using

the AIMS portal is that in the initial phase of its use,

in addition to providing specific information about a

particular term, in particular the creation of a list of

its entries in different languages, a hierarchical struc-

ture of URL links to the sites of a number of libraries,

thesauruses, dictionaries, etc. where available termi-

nological resources have a certain relation to the term

for which the query is formed (figure 3) is also gener-

ated.

An extremely important feature of this portal is the

hierarchical structure of the URL links, which allows

students to consciously determine the further steps to

take in order to find the necessary information about

the relevant term. In particular, all links are concen-

trated into categories: broader, narrower, exactMatch,

closeMatch, broadMatch, related. By organising the

resource links into these categories, translators can

focus their efforts on the resources that are of most

interest to them in the context of their particular as-

signment. The exactMatch category is by far the most

interesting as it groups the resources where you can

find the most accurate information on a given term.

However, the closeMatch category can also be inter-

esting, as the resources offered there can significantly

enhance the understanding of the nature of a term

and its application and translation terms. Overall, the

AIMS portal offers more than twenty of the world’s

leading terminology repositories, whose resources are

very powerful. A list of the main ones is given in ta-

ble 1.

An important resource that the Interactive Seman-

tic Web uses as original sites in the initial search

for information about a certain term is the UNESCO

Thesaurus. It contains a verified and structured list

of terms covering a rather broad thematic list in the

branches of the different sciences – natural sciences,

social sciences and humanities. Terms in the fields

of information and communication and education are

also presented. Structurally, the thesaurus is divided

into seven main thematic areas, which in turn are

divided into microthesauri. This clear hierarchical

structure allows a quick understanding of the essence

of the individual concepts and the connections be-

tween them. Each term is accompanied by an ex-

planation of its meaning, which helps to avoid mis-

takes in its use, and the designation of the number

and name of the microthesaurus to which it belongs.

When available, synonyms of varying degrees of ap-

proximation to the meaning of the term are also indi-

cated. These can be so-called broad, narrow or related

concepts. A broad term is represented as a reference

to a terminological element that is one level higher in

the thesaurus structure. A narrow term, on the other

hand, is reflected through a reference to a termino-

logical element one level lower in the thesaurus struc-

ture. Related terms are essentially related concepts.

Using of Resource Sources of Interactive Semantic Networks in Offline Translator Training

395

Table 1: Online terminology resources used when working with the Interactive Semantic Web.

The name of the online terminology resource Support and accompaniment

GEMET (General Multilingual Environmental Thesaurus) European Topic Centre on Catalogue of Data

Sources (ETC/CDS) and the European

Environment Agency (EEA)

The National Agricultural Library’s United States government

Agricultural Thesaurus and glossary

IATE (Interactive Terminology for Europe) European Union

TAUS (The language data Network)

SKOS UNESCO Thesaurus The University of Murcia (Spain),

SKOS UNESCO nomenclature for fields UNESCO Chair in Information

of science and technology Management in Organizations

Nuovo soggettario – Thesaurus The National Central Library of Florence

DBpedia University of Leipzig and Christian Bizer

from FU Berlin (now University of Mannheim)

UNESCO Thesaurus United Nations Educational,

Scientific and Cultural Organization

Standard-Thesaurus Wirtschaft Leibniz-Informationszentrum Wirtschaft

Katalog Der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Deutsche National Bibliothek

Skosmos THESOZ Thesaurus

AIMS (The Agricultural Information Management Food and Agricultural Organization

Standards Portal of the United Nations (FAO)

The Library of Congress Linked Data Service Library of Congress

Biblioth

`

eque Nationale De France

Chinese Agricultural Thesaurus (CAT) Agricultural Information Institute of CAAS

The structuring of terms in the UNESCO Thesaurus

is shown in figure 4.

A great advantage of using the UNESCO The-

saurus in a translator’s work is that this terminology

resource is quadrilingual, so the translator can use it

both to gain knowledge in order to better understand

the industry and therefore the context in which the

term is actualised, and directly for translation if the

target language is supported by this resource. There

are various options to search for a term’s description

and relationships, which can be done through an al-

phabetical list or in a hierarchical structure. Hierar-

chical search options for a term are shown in figure 5.

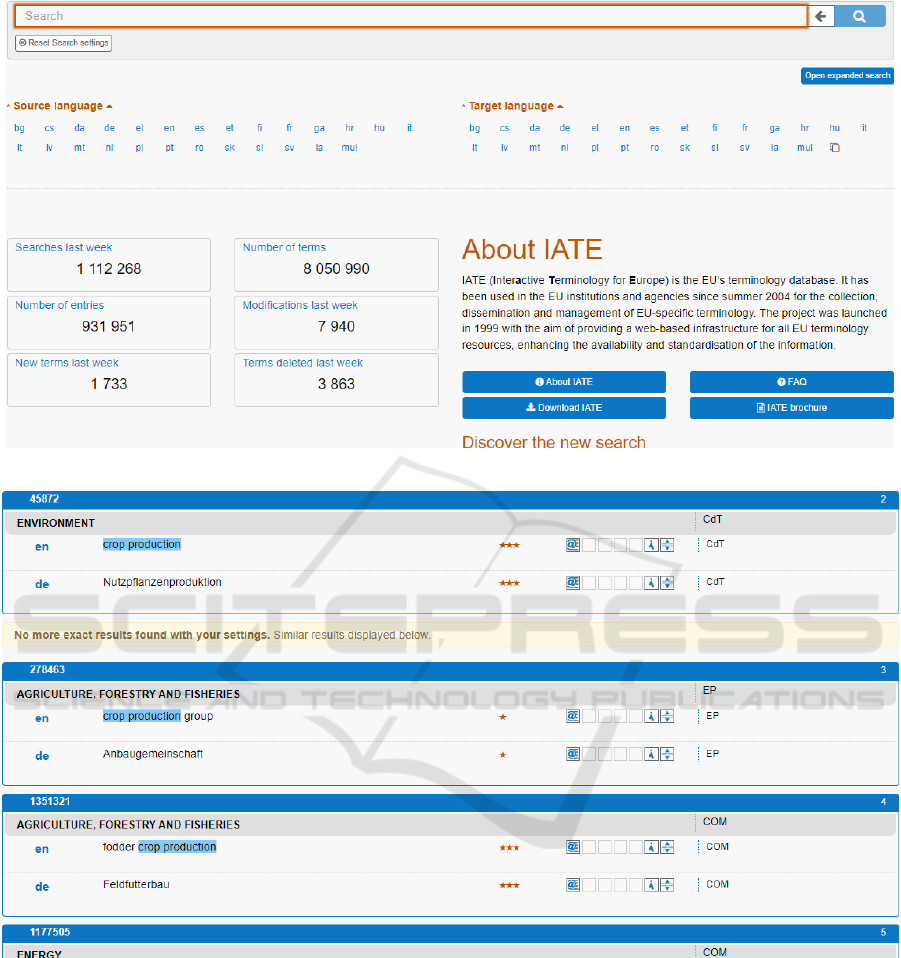

A valuable terminology resource is of course the

IATE (Interactive Terminology for Europe) database

(figure 6), created and maintained by the European

Union. It contains terminology that is used by EU

institutions and agencies, so referring to this termi-

nology database will enable a translator to use har-

monised and standardised terminology.

A special feature of the IATE terminology

database is that the search results not only match the

term in the target language but also the word com-

binations into which the term is included (figure 7).

This makes the translator’s job a lot easier, as there

can be direct matches for the purpose of his/her ter-

minology search. On the other hand, the terms are

given in their immediate context, which makes it eas-

ier for a translator who is not an expert in the relevant

field to understand their meaning.

As shown in figure 7, the term crop production can

be used in different sectors and domains – environ-

ment, agriculture, fish farming, and forestry. There-

fore, the results of the search for correspondences to

an English term in German are represented by these

semantic fields and, as we can see, there are different

terms in German as correspondences, depending on

the sector.

Before the experimental part of the study, which

involved the construction of an individual interactive

semantic network by the students on the terminology

of their choice, the experimental participants were

introduced to the terminology resources described

above and presented in table 1. The students could

choose any of the suggested terminology resources to

realise their goal.

AET 2021 - Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

396

Figure 4: Structuring of terms in the UNESCO Thesaurus.

Figure 5: Results of a search for the term “soil” in the UNESCO Thesaurus.

3.3 Development of a Personalised

Interactive Semantic Network with

Support for External Terminology

Resources

Given the development of the network to cover a

wider terminological spectrum, it is advisable to move

along the related type links. The results of the devel-

opment of the individual interactive semantic network

in different directions depending on the type of link-

age are shown in figure 8.

At this stage in the implementation of the tech-

nology for selecting and structuring sector-specific

terminology based on interactive semantic networks,

students can already begin to extract selected terms

Using of Resource Sources of Interactive Semantic Networks in Offline Translator Training

397

Figure 6: Interactive Terminology for Europe database.

Figure 7: Search results for the term “crop production” with English as the source language and German as the target language.

from the constructed network and place them into

the terminology database. In doing so, the students

must be made familiar with the criteria we have de-

fined for creating and completing terminology bases

in which it is appropriate to structure domain-specific

terminology derived from interactive semantic net-

works. In defining the criteria, we were guided pri-

marily by the possibility of further use of terminol-

ogy bases for such purposes as: learning foreign lan-

guages using mobile applications, mastering Com-

puter Aided Translation (CAT) systems, mastering

Computer Aided Interpretation (CAI) systems, which

corresponds to the logic of the developed technology.

To such criteria, we have classified:

• universality (ability to meet the need for termino-

logical support for different processes directly or

with minimal modification),

• structurability (possibility of placing terms), syn-

onyms, matches and other additional information

to the term in compliance with generally accepted

AET 2021 - Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

398

Figure 8: A individual interactive semantic network, developed along different lines depending on the type of relationship.

principles,

• convertibility (the ability to convert to other for-

mats for the needs of other systems without

changing the structure and content),

• extensibility (the possibility of changing the struc-

ture of the database to accommodate additional

information in the entry at any stage of its com-

pletion, without loss of data).

After being introduced to these criteria, the stu-

dents had to decide on their own about the software

to create the terminology database, the format of the

database and its initial structure. The autonomy given

to the students to make such decisions was due to their

experience with CAT and CAI and therefore with the

terminology bases used in such systems.

However, using the specialised functions of the in-

teractive semantic networks, the students were able

to obtain extended information about the terms de-

fined for entry into the terminology base, if neces-

sary. This toolkit is based on the interactive use of

online resources that can be accessed via external

links and which concentrate a considerable amount

of terminology indicating its affiliation to a domain,

its interpretation, definitions of terms, their matching,

etc. (figure 3). The online resources used include

powerful bases such as: Interactive Terminology for

Europe (IATE), General Multilingual Environmental

Thesaurus (GEMET), National Agricultural Library’s

Agricultural Thesaurus and Glossary, LusTRE (multi-

lingual Thesaurus Framework), TAUS (The language

data Network) etc.

Using the resources of such databases makes it

possible to extend the content of terminology bases

beyond the simple structure, containing only terms

and their matches, to the use of extended informa-

tion. In particular, the extension of each terminol-

ogy entry with additional information such as domain,

definition, synonyms, etc. (figure 9) contribute to in-

creasing their informative value. They can be useful

when such databases are used with automated transla-

tion systems. In this case, the terminology databases

should be structured with appropriate fields for struc-

turing such information.

In the list of links to external online resources

generated by the interactive semantic network, there

can also be resources containing additional informa-

tion in the form of multimedia documents, electronic

Using of Resource Sources of Interactive Semantic Networks in Offline Translator Training

399

Figure 9: Structure of the presenting additional information on the term “horticulture” in the online resource “National

Agricultural Library’s Agricultural Thesaurus and Glossary”.

documents, videos, books, images (figure 10). The

value of such resources in autonomous learning lies

not only in the selection of terminology for terminol-

ogy bases, but more in the opportunity to understand

in detail the nature of the term, the context of its use,

and to form an idea of defining the object. With this

technology of using semantic networks, students are

able to learn more about the objects of a particular do-

main through a terminological apparatus without be-

ing overloaded with redundant information.

It is important to note that a developed interactive

semantic network can be automatically converted into

another format for displaying its elements, namely by

hierarchical structure (figure 11). This format of pre-

senting the network allows students to enhance their

ability to explore the constructed network in terms

of the interrelationship of its elements, in particular

in the aspect of distinguishing more general concepts

from highly specialised vocabulary.

According to the scheme of technology for select-

ing and structuring sector-specific terminology (fig-

ure 1), working in the Hierarchy of concepts represen-

tation of the interactive semantic network, students

can also extract terms from it and add them to the ter-

minology base, but without the possibility of obtain-

ing additional information from the online resources.

3.4 Experimental Testing of the Use of

Interactive Semantic Networks with

External Terminology Resources in

Translator Training

In order to identify the possibilities and ways of us-

ing interactive semantic networks with external ter-

minology resources in the process of technological

training of translators, we conducted a survey of stu-

dents who were asked to experience them while they

were in distance learning, which created a situation

of autonomous learning. Thirty-eight students took

part in this type of experiential learning, learning how

to create terminology bases with a view to their fu-

ture use in foreign language learning using mobile ap-

plications and mastering the use of computer-assisted

translation systems. The questionnaire used for the

survey contained 11 questions and provided two alter-

native answers to each question “Yes” or “No”. The

content of the questionnaire, as well as summarised

quantitative data on the responses, are shown in ta-

ble 2.

The responses to the first question show a positive

effect on the learning of domain-specific terminology

bases precisely in the aspect of term identification and

selection technology in the lack of an in-depth un-

derstanding of the domain. This was made possible

AET 2021 - Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

400

Figure 10: Structure of presentation of additional information about the term “horticulture” in online resources in the form of

multimedia and electronic documents, videos, books, images.

Table 2: Results of a student questionnaire on the using interactive semantic networks.

Question

Response rate, %

Yes No

Did the use of interactive semantic networks help you acquire the skills? 78.9 21.1

Has the use of interactive semantic networks contributed to the identification of related

concepts and terms associated with a particular source term?

84.2 15.8

Has the visualised representation of the interactive semantic network contributed to an

understanding of the integrity of a particular field in which you are not an expert?

81.6 18.4

Has the use of an interactive semantic network enabled you to understand better the range

of components of a particular field in order to detail terminology in the right direction?

73.7 26.3

Does the presence of established relationships between the different hierarchical levels in

the interactive semantic network help to outline a terminology dataset for input into the

terminology database according to a certain logic?

76.3 23.7

Have you used MS Excel to create and complete your terminology database? 68.4 31.6

Have you used specialised CAT system modules to create and complete your terminology

base?

21.1 78.9

Have you used the functionality of computer-assisted interpreting systems to create and

complete your terminology base?

10.5 89.5

Did you fill your terminology database with additional information about the terms en-

tered?

34.2 65.8

Have you used the specialised functions of interactive semantic networks to find more

information about terms?

39.5 60.5

Have you needed to change the structure of your base in order to expand it? 13.2 86.8

Using of Resource Sources of Interactive Semantic Networks in Offline Translator Training

401

Figure 11: Presentation of the created interactive semantic network with a hierarchical structure.

precisely using interactive semantic networks, as in-

dicated by 78.9% of the students. A convincing proof

of the effectiveness of interactive semantic networks

was the responses to the second question of the ques-

tionnaire, as 84.2% of the students owe it to them to

be able to identify related concepts and terms related

to a certain source term. In other words, only 15.8%

of the students could identify the lexical field of cer-

tain terms based on their own prior knowledge in a

certain field.

The high number of affirmative responses to the

third question (81.6%) is most likely due to the

easier perception of information presented in visual

form, which is generally an effective support for au-

tonomous learning. In particular, the functionality

of the interactive network to visually reproduce the

terms of a particular area and the relationships be-

tween them contributed to an understanding of its in-

tegrity, even at an early stage of familiarity with it.

In addition, the use of an interactive semantic net-

work to highlight terms of a particular domain al-

lowed the students to detail the elements of the ter-

minological system in the right direction quite effec-

tively, as reported by 73.7%. This kind of activity is

directly related to the filling of terminology bases and

would have required significantly more time if done

by other means.

The availability of an automated function in the

interactive semantic network to generate relation-

ships between terms across the four hierarchical lev-

els proved to be an effective tool for 76.3% of the stu-

dents, who indicated that it allowed them to identify

the right set of terminology data to add to the termi-

nology database aimed at solving a specific problem.

The responses to the questions on the software that

the students used to create the terminology bases can

be explained by the influence of two factors, namely

the availability for use of a particular software prod-

uct and the level of proficiency in it. The fact that

68.4% of students chose MS Excel to create and com-

plete their terminology databases, confirms the fact

that the programme is commonly available and the ex-

perience of using it is acquired not only in the study

of specialised courses, but also in previous phases

of mastering information technologies. However, it

is important that 21.1% of the students created ter-

AET 2021 - Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

402

minology bases using specialised modules designed

to generate such bases when working with CAT sys-

tems. This indicates that a fairly large proportion of

students have not only mastered these modules to a

level which has enabled them to carry out such op-

erations at a higher technological level, but are also

aware of possible ways of obtaining and using them.

It is important to note that although only 10.5% of

students reported using the functionality of CAI sys-

tems to create and complete a terminology base, but

due to the relatively low prevalence of such systems,

this indicates that students valued certain aspects of

these systems and gave them preference over others.

Judging by the responses to the question about

finding and using additional information about terms,

more than a third of the students used the available

potential of interactive semantic networks for this pur-

pose. This is an indication that some of the students

were not only forming terminological bases, but also

trying to understand the essence of the industry in

more depth.

Analysing the high number of “No” responses

(86.8%) regarding the need to modify the structure

of the database in order to expand it, it can be stated

that the students had sufficient experience in design-

ing the structure of the terminology bases during the

creation phase. This allowed them to predict the nec-

essary fields for concentrating the information avail-

able in the semantic network about the term entered

in such a way that, in the vast majority of cases, they

met the requirements.

Overall, the results of the survey indicate the po-

tential of interactive semantic networks in the pro-

cess of technological training of translators, in partic-

ular for forming terminological bases for their further

use in learning foreign languages and mastering auto-

mated translation systems.

Given the rather broad list of available external

terminology resources related to interactive semantic

networks, we also found out which of these resources

the participants in the experiment preferred and why.

The results of the students’ choices are presented in

table 3.

The reasons given by the students for their pref-

erence for a particular terminology resource were as

follows:

• frequency of hyperlinks to this resource in the in-

teractive semantic web,

• availability of more detailed information about

this resource, obtained for familiarisation before

the experiment,

• amount of terminology data presented in the

database,

Table 3: Results of students’ choice of external terminology

resources.

Terminology resource name

Number

of cases

selected

UNESCO Thesaurus 17

IATE (Interactive Terminology for Eu-

rope)

11

The Agricultural Information Manage-

ment Standards Portal (AIMS)

4

THESOZ Thesaurus 3

The Library of Congress Linked Data

Service

3

• specific need for the terminology (e.g. a narrow

domain).

In view of these student considerations, it should

be noted that the small number of selections of some

resources is precisely due to the specific terminolog-

ical needs of the participants in the experiment and

the corresponding orientation of their chosen base.

Therefore, this in no way diminishes the value of any

terminology resources. At the same time, we have

concluded that attention needs to be paid to familiaris-

ing students in more detail with the large number of

terminology resources available.

Overall, the results of the survey indicate the po-

tential of interactive semantic networks in the pro-

cess of technological training of translators, in partic-

ular for forming terminological bases for their further

use in learning foreign languages and mastering au-

tomated translation systems. A separate value of this

potential is external terminology resources linked to

hyperlinks to interactive semantic networks.

4 CONCLUSIONS

In the process of technological training of translators,

it has been found that it is advisable to implement el-

ements of augmented reality in order to increase its

efficiency. One of these elements can be interactive

semantic networks, the technology of using which for

the selection and structuring of industry terminology

we have developed and tested in the conditions of au-

tonomous learning. This technology allows:

• create a personalised, interactive semantic net-

work to form a domain-specific terminology base,

• to develop a personalised, interactive semantic

network along various lines, depending on the

need for detailing and structuring domain-specific

terminology,

Using of Resource Sources of Interactive Semantic Networks in Offline Translator Training

403

• to select domain-specific terminology on the basis

of its detailing, taking into account the types of hi-

erarchical relationships of the interactive semantic

network,

• to get more information about terms through the

interactive use of external online resources, the

links to which are automatically generated by the

created semantic networks,

• to investigate the generated semantic networks in

the aspect of distinguishing more general con-

cepts from highly specialised vocabulary.

To structure the domain terminology selected on

the basis of interactive semantic networks we de-

fined the criteria of creation and filling terminolog-

ical bases, with possibility of their further use for

foreign language learning with mobile applications,

mastering computer aided translation (CAT) systems,

mastering computer aided interpretation (CAI). These

criteria are universality, structurability, convertibility,

extensibility.

The experimental use of the developed technology

in the process of autonomous training of translators

has shown a positive influence on their technologi-

cal training, in particular in the aspect of the ability

to define and select terms when there is no deep un-

derstanding of the domain, to detail elements of the

terminological system in the right direction, to create

terminological bases on the basis of selection and de-

tailing of terms using interactive semantic networks.

In order to informational-terminological support

of translators’ training and activities and to enhance

the use of interactive semantic networks, students

were additionally familiarized with external termino-

logical resources hyperlinked to the interactive se-

mantic networks. Because of the experimental use

of these resources in the process of building a cus-

tomised interactive semantic network, it was found

that they could meet the specific terminological needs

of a translator.

REFERENCES

Amelina, S. M., Tarasenko, R. O., Semerikov, S. O., and

Shen, L. (2022). Using mobile applications with

augmented reality elements in the self-study pro-

cess of prospective translators. Educational Technol-

ogy Quarterly, 2022(4):263–275. https://doi.org/10.

55056/etq.51.

Benson, P. (2005). Autonomy and information technol-

ogy in the educational discourse of the information

age. In Information technology and innovation in

language education, chapter 9, pages 173–193. Hong

Kong University Press, Hong Kong.

Cotterall, S. (2000). Promoting learner autonomy through

the curriculum: principles for designing language

courses. ELT Journal, 54(2):109–117. https://doi.org/

10.1093/elt/54.2.109.

Hurd, S., Beaven, T., and Ortega, A. (2001). De-

veloping autonomy in a distance language learn-

ing context: issues and dilemmas for course writ-

ers. System, 29(3):341–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/

S0346-251X(01)00024-0.

KCI (2022). Terminology tools and resources. https://

knowledge-centre-interpretation.education.ec.europa.

eu/en/content/terminology-tools-and-resources-0.

Little, D. (2002). Learner Autonomy and Second/Foreign

language Learning. In Bickerton, D., editor, The

Guide to Good Practice for Learning and Teaching

in Languages, Linguistics and Area Studies. LTSN

Subject Centre for Languages, Linguistics and Area

Studies, Southampton. https://www.researchgate.net/

publication/259874624.

Liu, D., Dede, C., Huang, R., and Richards, J., editors

(2017). Virtual, Augmented, and Mixed Realities in

Education. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.

1007/978-981-10-5490-7.

Moore, I. (2010). What Is Learner Autonomy? http:

//web.archive.org/web/20100325013329/https://extra.

shu.ac.uk/cetl/cpla/whatislearnerautonomy.html.

Murphy, L. (2006). Supporting learner autonomy in a dis-

tance learning context. In Gardner (ed.), pages 72–92.

Ochoa, C. (2016). Virtual and augmented reality in edu-

cation. Are we ready for a disruptive innovation in

education? In ICERI2016 Proceedings, 9th annual

International Conference of Education, Research and

Innovation, pages 2013–2022. IATED. https://doi.org/

10.21125/iceri.2016.1454.

Pemberton, R., Li, E. S. L., Or, W. W. F., and Pierson, H. D.,

editors (1996). Taking Control: Autonomy in Lan-

guage Learning. Hong Kong University Press, Hong

Kong. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2jc12n.

Reinders, H. (2006). Supporting independent learning

through an electronic learning environment. In

Lamb, T. and Reinders, H., editors, Supporting

Independent Language Learning: Issues and In-

terventions, volume 10 of Bayreuth Contributions

to Glottodidactics, pages 219–238. Peter Lang,

Frankfurt. https://innovationinteaching.org/docs/

book-chapter-2006-independent-learning-book.pdf.

Roche, C., Alcina, A., and Costa, R. (2019). Termino-

logical resources in the digital age. Terminology.

International Journal of Theoretical and Applied Is-

sues in Specialized Communication, 25(2):139–145.

https://doi.org/10.1075/term.00033.roc.

Scharle,

`

A. and Szab

´

o, A. (2000). Learner Autonomy: A

guide to developing learner responsibility. Cambridge

Handbooks for Language Teachers. Cambridge Uni-

versity Press, Cambridge.

Scrivner, O., Madewell, J., Buckley, C., and Perez,

N. (2016). Augmented reality digital technologies

(ARDT) for foreign language teaching and learn-

ing. In 2016 Future Technologies Conference (FTC),

AET 2021 - Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

404

pages 395–398. https://doi.org/10.1109/FTC.2016.

7821639.

Tarasenko, R. and Amelina, S. (2020). A unification of

the study of terminological resource management in

the automated translation systems as an innovative

element of technological training of translators. In

Sokolov, O., Zholtkevych, G., Yakovyna, V., Tara-

sich, Y., Kharchenko, V., Kobets, V., Burov, O., Se-

merikov, S., and Kravtsov, H., editors, Proceedings

of the 16th International Conference on ICT in Ed-

ucation, Research and Industrial Applications. Inte-

gration, Harmonization and Knowledge Transfer. Vol-

ume II: Workshops, Kharkiv, Ukraine, October 06-10,

2020, volume 2732 of CEUR Workshop Proceedings,

pages 1012–1027. CEUR-WS.org. https://ceur-ws.

org/Vol-2732/20201012.pdf.

Tarasenko, R. O., Amelina, S. M., and Azaryan, A. A.

(2020a). Improving the content of training future

translators in the aspect of studying modern CAT

tools. CTE Workshop Proceedings, 7:360–375. https:

//doi.org/10.55056/cte.365.

Tarasenko, R. O., Amelina, S. M., Kazhan, Y. M., and Bon-

darenko, O. V. (2020b). The use of AR elements in the

study of foreign languages at the university. In Burov,

O. Y. and Kiv, A. E., editors, Proceedings of the 3rd

International Workshop on Augmented Reality in Ed-

ucation, Kryvyi Rih, Ukraine, May 13, 2020, volume

2731 of CEUR Workshop Proceedings, pages 129–

142. CEUR-WS.org. https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2731/

paper06.pdf.

UNESCO (2022). Digital learning and transformation of

education: Open digital learning opportunities for all.

https://www.unesco.org/en/education/digital.

Yagcioglu, O. (2015). New Approaches on Learner Au-

tonomy in Language Learning. Procedia - Social

and Behavioral Sciences, 199:428–435. The Pro-

ceedings of the 1st GlobELT Conference on Teach-

ing and Learning English as an Additional Language.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.529.

Using of Resource Sources of Interactive Semantic Networks in Offline Translator Training

405