Computer-Mediated Communication and Gamification as Principal

Characteristics of Sustainable Higher Education

Anastasiia V. Tokarieva

1 a

, Nataliia P. Volkova

2 b

, Inna V. Chyzhykova

1,2 c

and Olena O. Fayerman

2 d

1

University of Customs and Finance, 2/4 Volodymyra Vernadskoho Str., Dnipro, 49000, Ukraine

2

Alfred Nobel University, 18 Sicheslavska Naberezhna Str., Dnipro, 49000, Ukraine

Keywords:

Computer-Mediated Communication, Educational Digitalisation, Gamification, Serious Video Games,

Inclusive Education, Socionomics.

Abstract:

Digimodernism and videoludification are the key drivers of present social transformations. Digital pedagogy,

gamification, game-based learning and serious video games (SVGs) supported by computer-mediated commu-

nication (CMC) come to the foreground. Theoretical overview of the CMC, discussion of SVGs for e-learning

in the time of the quarantine, two cases of SVGs’ implementation into educational contexts, efficiency mea-

surement of this implementation, comparison of obtained results with previous data are the aims of this article.

To achieve these aims, qualitative and quantitative research methods were applied. We defined ‘distance learn-

ing’, ‘e-learning’ based on CMC, collected their characteristics, quality parameters and modes. We revised

our previous work empirical data and conclusions. Later, we analysed ‘gamification’, ‘game-based learning’,

‘serious video games’ in contemporary education, presented two case studies of digital games’ integration

into educational process. We used a feedback form, a questionnaire, and a survey to measure the efficiency of

the e-learning courses. We proved that they serve as informative quantitative measurement. We emphasised

the topicality of the options for reorganising and refining distance and e-learning and brought forward the

idea about the new vision of distance and e-learning, gamification of educational process and serious video

games as one more variation of CMC that must drive our decisions about the use of technology, not vice versa.

Therefore, the need to develop teacher-training programs to help educators understand, design, evaluate and

apply CMC and gamified learning applications is set up as the vector of future work.

1 INTRODUCTION

The contemporary educational environment in

Ukraine, as well as in many other countries, is driven

by the post-industrial model of society and post-

modernism that underlie rapid social changes. The

transition from goods’ production to the economy

of services, extensive application of information and

communication technologies, innovation, creativity

and entrepreneurship, international travel, and mi-

gration serve as the main characteristics of societal

models. In the workplace, it is characterised by

professional flexibility and diversity; tasks, projects,

and networks; the necessity to work in a team,

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8980-9559

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1258-7251

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2722-3258

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2487-4063

technological complexity within a rapidly changing

environment. Therefore, the very concept of ‘ed-

ucation’ is currently being revised to support the

postmodern era based on such competencies as social

and emotional intelligence, media literacy, ecological

intelligence, creativity, collaboration and participa-

tory problem-solving (Tokarieva et al., 2019). Today,

there is an obvious need to address the demands of

adult and senior learners as well. That is why, educa-

tion now is being viewed as a process of individual

development, the empowerment with knowledge

from birth to death – the process that involves inter-

connectedness and interdisciplinarity, encouragement

of students’ autonomy in the form of self-guided

learning and self-guided education enhancement.One

of the important concepts of today’s educational

systems is ‘ecosystemic relations’ – individually

oriented, based on the principles of autonomy, access

to information and feedback,distributed powers, cre-

Tokarieva, A., Volkova, N., Chyzhykova, I. and Fayerman, O.

Computer-Mediated Communication and Gamification as Principal Characteristics of Sustainable Higher Education.

DOI: 10.5220/0012065700003431

In Proceedings of the 2nd Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology (AET 2021), pages 515-528

ISBN: 978-989-758-662-0

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

515

ativity to solve problems, responsibility, dynamism,

teamwork to jointly solve global problems (Luksha

et al., 2018, p. 34-47). Education in the postmodern

context is based on problem and project tasks without

fear of making mistakes; play/game-based learning,

game universes, virtual augmented reality, and

computer-mediated communication (CMC), which

have come to the foreground in the present context

of COVID-19 lockdown and the after-pandemic

period when pedagogies turned from in-personal to

virtual instructions, including distance learning and

e-learning to maintain the barrier-free educational

environment.

Therefore, the discussions around educational

digitalisation and CMC’s implementation into vari-

ous educational contexts continue to gather momen-

tum and are reflected in many contemporary national

and foreign scholarly works. For example, the scien-

tific inquiry of Andreev (Andreev, 2013) is connected

with didactics of distance learning, while Fedorenko

et al. (Fedorenko et al., 2019) analyses the questions

of informatisation in Higher Educational Institutions

(HEIs). Bramble and Panda (Bramble and Panda,

2008) present the various distance and online learn-

ing models. Dabbagh and Bannan-Ritland (Dabbagh

and Bannan-Ritland, 2005) focus on online learning

concepts, strategies, and application. Palloff and Pratt

(Palloff and Pratt, 1999) describe effective strategies

for an online classroom. Rice (Rice, 2006), Bor-

dia (Bordia, 1997), Androutsopoulos (Androutsopou-

los, 2006), Dahlberg (Dahlberg, 2001), Kock (Kock,

2004), Hardaker (Hardaker, 2010), Joinson (Joinson,

2001), Walther (Walther, 1996) – these are just a few

researchers’ names to add to the list, which proves

that both theoretical and practical interests in enhanc-

ing ways and methods based on CMC are topical on

the global scientific scale (Artemyeva et al., 2005).

The literature review would be incomplete if we

do not mention here the scholarly works about educa-

tional gamification and educational video games. For

example, the definition and the structural characteris-

tics of the gamification phenomenon are discussed by

Deterding (Deterding, 2012). Education via gamifica-

tion is analysed by Huotari and Hamari (Huotari and

Hamari, 2012). Professional corporate training based

on gamified applications is presented by Baxter et al.

(Baxter et al., 2017). More recent studies, including

works of Arnab et al. (Arnab et al., 2015), Becker

(Becker, 2017), discuss the formal design paradigm

for serious games. Wouters et al. (Wouters et al.,

2013) present the analysis of motivational and cog-

nitive effects of video games. Questions related to

the game-based curriculum are analysed in theses of

Alkind Taylor (Alkind Taylor, 2014) and Marklund

(Marklund, 2015).

Considering this, the purpose of the article is to

give an overview of the computer-mediated commu-

nication modes and means, as well as serious video

games (SVGs) used for e-learning in the time of the

quarantine by the university faculty; to present two

new cases of SVGs’ implementation into educational

contexts; to discuss the efficiency of the implementa-

tion based on ‘The Instructional Materials Motivation

(IMMS)’ survey by Keller (Keller, 2010b) and a feed-

back form developed by the research team; to com-

pare the obtained results with the previous research

data (Tokarieva et al., 2021).

Stemming from the aim, the following research

tasks were outlined:

1) to generalise the main theoretical and experiential

findings related to CMC modes and means;

2) to discuss in more detail gamification and SVGs in

the context of contemporary educational reality;

3) to present two case studies based on SVGs’ ap-

plication to the learning process and evaluate the

efficiency of this tool;

4) to compare the statistical data with the data from

our previous research work;

5) to make the conclusions and draft the vectors for

future research.

2 RESEARCH METHODS

To address the purpose of the article, a complex of

qualitative as well as quantitative research methods

was applied. Data collection methods were tied in

with the tasks set in the research. There are four dis-

tinct stages of the present research work.

Stage number one – theoretical analysis of CMC

(its means and modes) on which a literature study,

backed up by general references, primary and sec-

ondary resources’ analysis, a computer search of

www and databases were used. On this stage the no-

tions ‘distance learning’, ‘e-learning’, ‘modes of e-

learning’ were studied in depth. We also revised the

earlier received statistical data of the research con-

ducted by the authors in 2020 in Prydniprovska State

Academy of Civil Engineering and Architecture, the

Department of Foreign Languages, related to CMC

(Tokarieva et al., 2019).

On stage number two, we traced the transition

from CMC application in education to its gamifica-

tion, analysed the notions of ‘gamification’, ‘game-

based learning’, ‘serious video games’, highlighted

the difference between ‘serious video games’ and

AET 2021 - Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

516

‘computer games’. We based this analysis on the re-

vision and extension of our previous theoretical re-

search (Tokarieva et al., 2019).

The theoretical part is supplemented with two case

studies: an integration of ‘Globall Manager’ – a dig-

ital game for learning – into Cross-Cultural Commu-

nication course for students of Philology; and ‘Auti-

Sim’ and ‘Prism’ – games for learning and training of

Educators, Psychologists and Social Workers for in-

clusive education that we undertook on the third stage

of the present work. To evaluate the effectiveness

of these innovative learning tools we used ‘The In-

structional Materials Motivation (IMMS)’ survey by

Keller (Keller, 2010b) and a feedback form at the end

of the study programmes. The criteria of the effi-

ciency of the instructional material evaluation com-

prised the following parameters: attention – the in-

corporation of a variety of tactics to gain learner’s

attention; relevance – the consistency of the instruc-

tional material with students’ goals, learning styles

and past experiences; confidence – helping students

establish a positive attitude, drive for success; satis-

faction – is the maintenance of positive feelings about

learning experiences, i.e. positive rewards and recog-

nition (Keller and Suzuki, 2004; Keller, 2010a). On

this stage we also used a Google Forms with multi-

ple choice/unlimited choice questions to better under-

stand the participants’ experiences with video games.

The fourth stage and the task were to compare the

results of the case studies with earlier data, collected

at Prydniprovska State Academy of Civil Engineer-

ing and Architecture, the Department of Foreign Lan-

guages during March-May, 2020 connected with the

measurement of the e-learning courses’ design effi-

ciency for which the above-described ‘The Instruc-

tional Materials Motivation (IMMS)’ survey that con-

sists of 4 subscales and 36 items was used. The learn-

ers’ motivation levels were measured by applying a

5-point symmetrical Likert scale.

The authors of the article participated in the de-

velopment of the framework for the ‘Globall Man-

ager’ game integration into Cross-Cultural Commu-

nication course, implemented the game into the ed-

ucational process. Also, we collected and analysed

the data from ‘The Instructional Materials Motivation

(IMMS)’ survey, feedback forms about e-learning at

the time of the quarantine; Google Forms results after

‘Auti-Sim’ and ‘Prism’ games work with educational

and scientific student group ‘Fundamentals of Sup-

port for Children with Special Needs and their Fami-

lies for Pre-Service Specialists’ Training in the Socio-

nomic Sphere’.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Stage One

We begin our results’ discussion with the statement

that because of the increased importance of interna-

tional work settings, much of what we do and how

we communicate have moved to the Web. Commu-

nication, access, and creation of information have be-

come everyday life and work tasks that rely on the use

of personal and networked technologies. Nowadays,

we use Computer Mediated Communication (CMC) –

any human communication that occurs through the

use of two or more electronic devices and is exten-

sively used in distance and e-learning – to get news

updates from around the world, to research ideas,

exchange photos, publish our thoughts, tell people

where we are and share experiences of all kinds. This

includes text messages, e-mails, blogs and discussion

forums, social networks, virtual worlds, etc.

The focus of our present discussion is ‘distance

learning’, ‘e-learning’, ‘modes of e-learning’.

There are many definitions of the term ‘distance

learning’ that reflect the diversity of approaches to its

understanding. In the most profound studies of the

phenomenon done by Andreev (Andreev, 2013), we

can find the following definitions:

• distance learning is a mode of learning, along with

full-time and part-time modes, in which the edu-

cational process uses the best traditional and inno-

vative instructional techniques and tools, as well

as the forms of learning based on computer and

telecommunication technologies;

• distance learning is a purposeful asynchronous

process of interaction between the subject and the

object of learning mediated by electronic instruc-

tional tools, where the learning process does not

depend on the spatial location of the participants;

• distance learning is a set of educational services

provided to the general public in the country and

abroad through a specialised information educa-

tional environment based on the exchange of edu-

cational information at a distance.

Palloff and Pratt (Palloff and Pratt, 1999) distin-

guish three main characteristics of distance learning:

1) it does not depend on spatial location and time;

2) services are provided through a specialised infor-

mation environment; 3) learning process is controlled

by a student him/herself.

The history of distance learning can be traced

more than two centuries back and is connected

with the emergence of the correspondence institution.

Other forms of communication developed during the

Computer-Mediated Communication and Gamification as Principal Characteristics of Sustainable Higher Education

517

period of industrialisation and are associated with the

invention of the radio and television, i.e., radiocourses

and television courses. Later on, the appearance of

the World Wide Web played the most significant part

in the spread of the remote mode of learning. Conse-

quently, the historical development of distance learn-

ing is reflected in its models’ evolution – on the ba-

sis of a correspondence mode, an online mode, an e-

learning mode (Bramble and Panda, 2008).

The term ‘e-learning’ also has a big number of in-

terpretations and is used in different ways, depend-

ing on pedagogical goals and contexts. Our search

for e-learning definitions via Google Search Engine

yielded 1330000 entries. The generalised definition

of e-learning describes it as a variation of distance

learning that has gained active development due to the

emergence of new technologies.

It is true that the e-learning model is the latest

in the history of distance education and has a three-

dimensional structure. Through the training based on

e-learning principles, students can acquire knowledge

anywhere, anytime, and at any speed (Im, 2006).

The Instructional Telecommunications Council

defines distance education as “the process of ex-

tending learning, or delivering instructional resource-

sharing opportunities, to locations away from a class-

room, building or site, to another classroom, building

or site by using video, audio, computer, multimedia

communications, or some combination of these with

other traditional delivery methods” (Dalziel, 1998).

The European e-Learning Action Plan defines e-

learning as the use of the latest multimedia technolo-

gies and the Internet with the aim to improve the qual-

ity of the education through granting access to re-

sources and services, distance exchange, and coop-

eration (Beauvois, 1997).

According to the method of interaction, such

modes of e-learning can be distinguished: the in-

teraction between a student-electronic environment,

student-student, student-teacher, teacher-electronic

environment, interaction inside the educational com-

munity. According to the time criterion, e-learning

organisation is classified as asynchronous (different

times of teaching and learning), synchronous (teach-

ing and learning take place at the same time), or

a combination of the two. For example, asyn-

chronous communication (e-mail) allows using au-

thentic speech and meaningful context. Compared

to face-to-face communication and synchronous on-

line tools, this environment gives students enough

time to reflect and formulate their utterances. Syn-

chronous communication – real-time communication

(text chats) simulates conversation but is not compli-

cated by the possible ‘dominance’ of direct discus-

sions. Research confirms the fact that students par-

ticipate more often and more proportionately in on-

line discussions than in face-to-face communication.

It should also be added that online discussions create

a student-centred environment in which they are more

willing to take risks (Abrams, 2006).

According to the criterion of technological means’

utilisation, e-learning can be computer-based, laptop-

based, video conferencing-based, forums-based,

weblogs-based, etc. By the methods of information

transfer – text, sound, picture, video, animation, sim-

ulation, interactive resources based, etc.

In our article, we use the term ‘e-learning’ broadly

to relate to the learning environments where CMC is

used as a fundamental of educational instruction.

We consider it necessary to illustrate the above-

presented theoretical reflections with the summative

overview of the empirical results obtained at the De-

partment of Foreign Languages, Prydniprovska State

Academy of Civil Engineering and Architecture at the

time of the quarantine, the year 2020.

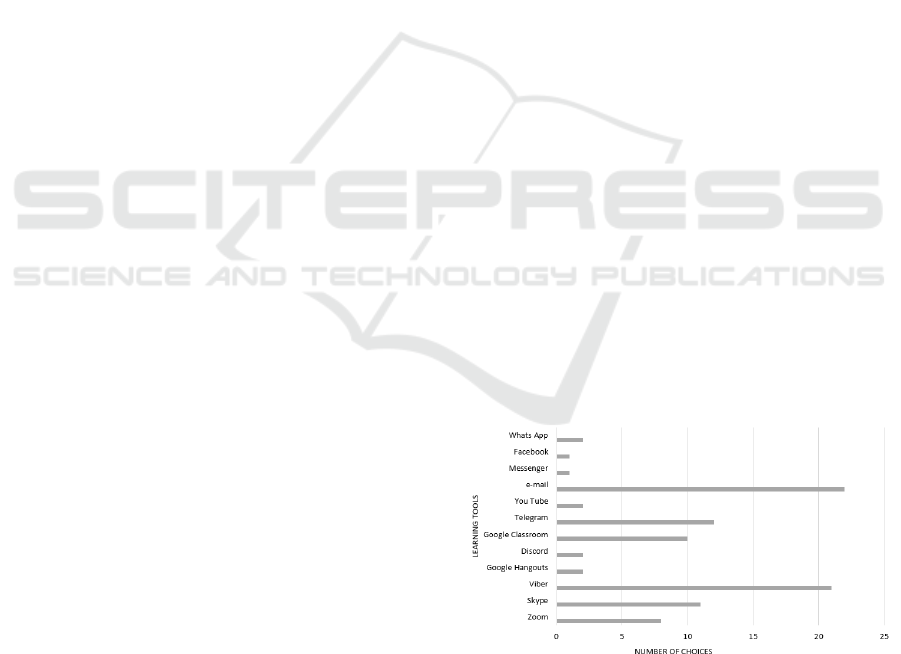

Based on the statistics received from ‘Analysis

of the E-Learning Tools Preferences’ form dissem-

inated among the teaching staff of the department

(the sample of 30 teachers), the most popular video-

conferencing platforms chosen by teachers of the de-

partment were Skype and Zoom, while Google Hang-

outs and Discord with video-conferencing features

were found less popular. The popularity of Viber

is also explained by its video-conferencing function.

Social networking apps that were actively used by

the faculty were Telegram and Viber. E-mail service

was also chosen for the asynchronous correspondence

with students. Google Classroom was applied by in-

structors to exchange texts, audio, video, and hyper-

linked material (figure 1).

Figure 1: E-learning tools preferences.

Our experience has also provided qualitative data.

For example, the benefits of Skype’s application, ac-

cording to our staffs’ opinion, lie in the number of

video chat participants (which is unlimited), the ease

of operation on the screen, the inclusion of such

activities as speaking, reading, and, partially, writ-

AET 2021 - Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

518

ing. Regarding the use of Google Hangouts appli-

cation, which is almost identical to Skype, a ‘Share

Screen’ feature that lets students see what the instruc-

tor demonstrates on the monitor: files, videos, etc., a

‘Chat History’ feature that records the number of peo-

ple attending each class are regarded as supportive. At

the same time, it does not have a file-sharing feature

and the number of video chat participants is limited

up to 10. When it comes to written assignments, the

Google Classroom application is named as the best

fit. Here, an instructor posts assignments and sets

up the deadline, selects students for whom the tasks

are assigned, evaluates students’ works (the number

of points is selected on a different scale principle fol-

lowing the instructor’s choice). It is also interesting

to mark here that back in March-May 2020 Google

Meet was not as popular an application as it is now.

A separate part of our discussion was given to the

Zoom platform’s analysis, as teaching on this plat-

form, judging by our teachers’ feedback, is challeng-

ing. This is connected with the phenomenon, de-

scribed as ‘Zoom fatigue’.

Those teachers who used this video-conferencing

platform complained that after two sequential ses-

sions they were more tired than after the same num-

ber of face-to-face lessons in a real class setting. One

of the explanations for this is provided by (Joosten,

2022). She attributes it to the Gallery view when

all the sessions’ participants appear, which challenges

the brain’s central vision, forcing it to decode many

people at a time. Moreover, ‘one of those boxes on the

screen is you’, which may mean that we spend more

energy on monitoring our non-verbal communication

than we do in person (Supiano, 2020). What we also

experienced was a shift towards teacher-centricity and

one-way communication that contradicts the conclu-

sions of the Instructional Telecommunications Coun-

cil about the effectiveness of e-learning that lies in

its individually-oriented nature and student-centricity

(Dalziel, 1998).

On this stage, we also organised a brief question-

ing of students as to what most difficult aspects of e-

learning they could name. The question we asked was

‘What is the most challenging for you in e-learning?’

The possible alternatives were pre-formulated for the

students to choose from and the number of choices

was not limited. Our statistics look as follows:

1. Problems with self-organisation, high level of dis-

traction – eight students – 34.8%.

2. The excessive number of educational tasks – eight

students – 34.8%.

3. Dependence on technical means – twenty stu-

dents – 86.9%.

4. Poor quality of home Internet – fourteen stu-

dents – 60.8%.

5. Restrictions on obtaining practical skills – five

students – 21.7%.

6. Lack of opportunity to communicate freely with

the teacher – none – 0%.

7. Lack of control over the level of knowledge –

three students – 13.04%.

8. Insufficient duration of classes (time limit) –

none – 0%.

9. The quality of the material taught – four students –

17.4%.

10. Insufficient theoretical materials to perform tests

and/or tasks – seven students – 30.4%.

11. Lack of opportunity to communicate with other

students – thirteen students – 56.5%.

12. The need to learn how to work online – three stu-

dents – 13.04%.

It is necessary to mention here, that we had a

chance to compare the results of our questionnaire

with the results, obtained in Alfred Nobel University,

Dnipro from the same questionnaire introduced dur-

ing the period from 8 to 14 April 2020 in electronic

form. The total number of interviewees there made up

1062 students. According to the form of education,

the interviewed students were distributed as follows:

• full-time students – 911 people – 85.8%;

• part-time students – 24 people – 2.3%;

• correspondence courses’ students – 127 people –

12%.

Alfred Nobel University’s statistics look as fol-

lows:

1. Problems with self-organisation, high level of dis-

traction – 351 students – 33.1%.

2. The excessive number of educational tasks – 330

students – 31.1%.

3. Dependence on technical means – 302 – 28.4%.

4. Poor quality of home Internet – 300 – 28.2%.

5. Restrictions on obtaining practical skills – 286 –

26.9%.

6. Lack of opportunity to communicate freely with

the teacher – 249 – 23.4%.

7. Lack of control over the level of knowledge –

186 – 17.5%.

8. Insufficient duration of classes (time limit) – 162 –

15.3%.

9. The quality of the material taught – 122 – 11.5%.

Computer-Mediated Communication and Gamification as Principal Characteristics of Sustainable Higher Education

519

10. Insufficient theoretical materials to perform tests

and/or tasks – 110 – 10.4%.

11. Lack of opportunity to communicate with other

students – 108 – 10.2%.

12. The need to learn how to work online – 55 – 5.2%.

Based on the comparative analysis, we got very

close statistical data on statements one, two, five,

seven, and eight, though the size of the samples in-

terviewed varied.

Overall, the results of this stage can be sum-

marised as follows: distance learning and its later ver-

sion – e-learning should be applied with the organi-

sational culture analysis in mind. The most popular

video-conferencing platforms named by the faculty

are Viber, Skype, and Zoom, while Google Hangouts

and Discord are found less popular. Social network-

ing apps actively used by the faculty are Telegram,

Viber. The most debatable is the Zoom platform as,

on the one hand, it has a lot of advantageous features

both for teachers and students. At the same time, such

a phenomenon as ‘Zoom fatigue’ is marked by the

faculty as a disadvantageous one.

With the reference to the students’ feedback from

as for the e-learning during the quarantine – ‘depen-

dence on technical means’ is named as the main chal-

lenge, followed by the poor quality of the Internet,

problems with self-organisation, the number of tasks

given, the restriction on exercising practical skills,

which helps highlight the current e-learning situation

in HEIs, reveal challenges and needs to further action.

3.2 Stage Two

Moving on to the discussion of the second task, we

would present the idea expressed by Kirby (Kirby,

2006) that digimodernism is the mainstream cultural

logic of contemporary society and both the video

game (as another variation of CMC) and the video

gamer are its principal object and subject. In broad

context, video games have fitted perfectly well in the

globalised spider-web of information flows and have

generated revenues as high as C22 billion in Europe in

2020 according to Global News Wire, with the num-

ber of people playing video games 1.553.5 million

worldwide. 51% of the EU’s population played video

games, which equals to some 250 million players in

the EU, the average playtime per week was 8.6 hours

(Interactive Software Federation of Europe, 2022).

As a response, digital pedagogy, gamification, game-

based learning, and serious video games are gradually

becoming a part of the everyday toolkit of educators

(figure 2).

Gamification is the use of game elements (such as

points, badges, leader boards, competition, achieve-

Figure 2: Video games in broad context.

ments) in a non-game setting with the aim to turn

routine tasks into more refreshing, motivating expe-

riences (Deterding, 2012). The main idea of gamifi-

cation evolved parallel with the Internet. Gamifica-

tion is based on the basics of games, though, with the

development of mobile phones and applications, it is

actually can be used almost in every sphere, includ-

ing education. For example, interactive quizzes like

‘Kahoot’, ‘Quizlet’, ‘ClassDojo’, ‘Duolingo’, ‘Ed-

modo’ or gamified learning management systems like

‘Classcraft’, ‘Lingua Attack’, ‘Socrative’, ‘DyKnow’.

At the same time, serious video games are those

that are built on game-based learning principles, in-

clude basic elements of video games, and are used

not for the entertainment (Zemliansky and Wilcox,

2010). The examples here are many, including educa-

tional games (or games for learning, like ‘Code.org’,

‘GloBall Manager’, ‘MinecraftEdu’), games for train-

ing (e.g. ‘AbcdeSIM’, Kognito, ‘Auti-Sim’, ‘Prism’),

games for change (or social games, like ‘Against all

Odds’, ‘Ayiti – The Cost of Life’, ‘Copenhagen Chal-

lenge’).

We think it necessary to note that ‘video games’

are considered an activity that includes one or more

players, has definite goals, rules, limitations, rewards

and outcomes, is artificial with the element of a com-

petition. At the same time, ‘serious video games’ are

those that are built on game-based learning principles,

include basic elements of video games and are used

not for the entertainment (Zemliansky and Wilcox,

2010).

Game-based learning (GBL) is a type of game-

play with defined learning outcomes (Shaffer et al.,

2005). In the process of GBL, learners use games

as a tool to study a topic or related topics. They

work individually or in teams. It is expected that in

this process, the use of games will enhance the learn-

ing experience through challenge, exploration, inter-

action, reflection, and decision-making while main-

AET 2021 - Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

520

taining a balance between the content, gaming, and

its application to the real world. Having a play at

its base, game-based learning is effective in motivat-

ing and improving students’ engagement, promoting

creative thinking and developing approaches towards

multi-disciplinary learning. As for educational digital

games – they proved to hold great promise for instruc-

tion that is appropriate for today’s learners.

Based on our previous research revision, we may

state that video games present a different learning en-

vironment (with a wide spectrum of built-in assistive

features) where players interact, experiment, discover

and research. They are good at helping to memo-

rise studied material (at ‘grinding’ things). The ma-

terial studied in games is stored longer in players’

memory. Games let play through the same situa-

tion applying different behavioural models, methods

and approaches. Games are cost-effective and effi-

cient in training for hazardous situations (firefight-

ers, ambulance, pilots). Games appeal to different

learning styles (visual, audio, kinesthetic). Games

are adaptable to a particular player’s level (with the

increase of difficulty based on the player’s perfor-

mance). Games help develop movements’ coordina-

tion and spatial sensation. As a novel educational in-

strument, games increase motivation. Games stim-

ulate players’ interaction, participation, discussion,

and reflection (Tokarieva et al., 2019).

3.3 Stage Three

The third stage of our article is connected with the

description and the discussion of two cases of seri-

ous games’ implementation into the educational pro-

cess. The first game for learning that was used is

‘GloBall Manager’ game that was developed within

the GA-BALL (‘Game-Based Language Learning’)

project – a joint project between the Engineering Fac-

ulty of Porto Politech Institute (ISEP), Virtual Cam-

pus Porto, Technical University of Gabrovo (Bul-

garia) and Federal University Pelotas (Brazil) (Edito-

rial Team, 2013). The main objective of the project

was to improve students’ linguistic and sociocul-

tural skills, necessary to take part in e-marketing

and e-commerce; develop skills to establish con-

nections via social platforms; encourage students

to entrepreneurial activity. The methodological ap-

proach chosen – the application of a video game

as a learning tool that would provide the partici-

pants with rules, everyday professionally-oriented sit-

uations, create a cooperative environment in which

players try to reach specific educational goals, and in-

crease personal skills and social competencies. The

game can be played in seven languages through six

different scenarios: 1) internationalisation diagnos-

tics; 2) participation in a fair; 3) business culture;

4) e-commerce and e-marketing management; 5) on-

line communication; 6) institutional negotiation (fig-

ure 3).

Figure 3: Globall Manager game (Virtual Campus Lda,

2015).

The game was implemented into the Cross-

Cultural Communication course delivered for the

four-year course students of Philology, University of

Customs and Finance, Dnipro, Ukraine. The aim of

the course is to study intercultural professional com-

munication, develop cross-cultural sensitivity of stu-

dents, form theoretical knowledge about the essence,

communication structure and its peculiarities in a

cross-cultural environment; linguistic, psychological

and socio-cultural features of cross-cultural commu-

nication; development of the skills that can help

students be effective in intercultural communication.

The game was used at practical classes one time

per week, 30 minutes for each session during the

first semester of 2021. The game was demonstrated

from the main (lecturer’s) computer. Students’ work

was initially organised as individual, pair or mini-

group work and in online learning mode later on – as

teacher-class interaction. Business Culture Scenario

was chosen as the study material and was played from

the beginning till the end. The scenario was played in

English. 46 students were enrolled in the course.

It is important to say that the above-presented

game was used as the study material, around which

lesson plans were developed. It is an acknowledged

fact that educational digital games’ integration into

a specific educational context is a complex process

as, during a digital game-based lesson, a teacher acts

as tech support, IT administrator, a moderator, a de-

briefer. The teacher may be an active player and pro-

vide feedback from ‘inside’ the game. Also, there

are three distinct stages in a digital game-based les-

Computer-Mediated Communication and Gamification as Principal Characteristics of Sustainable Higher Education

521

son, i.e., before the game-play stage, during the game-

play stage, after the game-play stage, accompanied

by preparing a lesson plan, setting up the game-play

situation, guiding learners in the game-play process,

finalising game-play experience.

We also wanted to understand the quality of the

course with a video game integrated into it. There-

fore, we organised a survey based on ‘The In-

structional Materials Motivation Survey (IMMS)’ by

Keller (Keller, 2010a).

There are several models that help estimate the

quality of e-learning. The existing models can be di-

vided into two categories: those based on empirical

data and those based on theoretical developments. An

example of the first category is the quality model pro-

posed by the Institute for Higher Education Develop-

ment ‘Quality on the Line: Success Factors for Dis-

tance Learning’ (IHEP, 2000); ‘Critical Success Fac-

tors in Online Education’ by Volery and Lord (Vol-

ery and Lord, 2000). The second category includes

model ‘Seven Principles for Good Practice’ by Chick-

ering and Gamson (Chickering and Gamson, 1987);

model ‘Quality Guidelines for Technology-Assisted

Distance Education’ by Barker (Barker, 1999); ‘The

E-learning Maturity Model’ by Marshall (Marshall,

2010) (Masoumi and Lindstr

¨

om, 2012).

There are also a number of models that have been

developed to measure the quality of a course (in-

cluding distance learning) through measuring learn-

ers’ motivation in order to improve a course design

or to adapt a course to learners’ motivational needs

(Keller and Suzuki, 2004). The questions of motiva-

tion, its structural components and measurement have

been studied from different theoretical perspectives in

the context of the Social Cognitive Theory, the Ex-

pectancy Value Theory, the Self Determination The-

ory (Silva et al., 2018).

Keller (Keller, 2010a) has developed and tested

a model known as the ARCS model based on its

acronym (Attention, Relevance, Confidence, and Sat-

isfaction).

Attention – is the importance of incorporating a

variety of tactics to gain learner’s attention by the

use of interesting graphics, animation, an event that

introduces a conflict, mystery, unresolved problems,

and other techniques to stimulate the inquiry in learn-

ers. Relevance – the consistency of the course and

the instructional material with students’ goals, learn-

ing styles, and past experiences. The connection of

the content to the learners’ future jobs or interesting

topics.

Confidence – lies in helping students establish a

positive attitude, drive for success, and the experience

of success as the result of their ability and efforts.

Satisfaction – is the maintenance of positive feel-

ings about learning experiences, i.e., positive rewards

and recognition (Keller and Suzuki, 2004).

The main ideas behind the ARCS model are that

motivation is influenced by the degree to which a

teacher and the instructional materials arise curios-

ity, are personally relevant with challenge levels that

promote confidence, and do not contain stressors that

would inhibit students’ effort (Keller, 2010a).

The ARCS model and the IMMS inventory (that

is an integral part of it) can be used with print-based

self-directed learning, computer-based instruction, or

online courses, have been successfully applied to dif-

ferent educational settings and proved to be informa-

tive as an instrument for the efficiency of a course

measurement (Huang and Hew, 2016).

The IMMS (the Instructional Materials Motiva-

tion) survey consists of 36 items and 4 subscales.

The 4 subscales are attention (12 items), relevance

(9 items), confidence (9 items), and satisfaction (6

items). It measures learners’ motivation level by ap-

plying a 5-point symmetrical Likert scale.

We consider it necessary to give here examples of

questions for each of the subscales.

Examples for the ‘Attention’ subscale: ‘There was

something interesting at the beginning of this course

that got my attention’. ‘These materials are eye-

catching’. ‘This course is so abstract that it was hard

to keep my attention (an example of a reverse ques-

tion)’.

Examples for the ‘Relevance’ subscale: ‘It is clear

to me how the content of this material is related to

things I already know’. ‘There were stories, pictures,

or examples that showed me how this material could

be important to some people’. ‘The content of this

material is relevant to my interests’.

Examples for the ‘Confidence’ subscale: ‘When I

first looked at this course, I understood it would be

easy for me’. ‘This material was more difficult to un-

derstand than I would like it to be (a reverse ques-

tion)’. ‘After working on this course for a while, I felt

confident that I would be able to pass a test on it’.

For the ‘Satisfaction’ subscale: ‘Completing the

exercises in this course gave me a satisfying feeling

of accomplishment’. ‘I enjoyed this course so much

that I would like to know more about this topic’. ‘I

really enjoyed studying this course’. ‘The wording of

feedback after the exercises, or of other comments in

this course, helped me feel rewarded for my effort’

(Keller, 2010a).

46 four-year students of Philology enrolled in the

Cross-Cultural Communication course took part in

the survey. The data we obtained are presented in the

table 1.

AET 2021 - Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

522

Table 1: Motivation level range.

Motivation

level

Scores

Number of

participants

(N = 46)

Percentage

High 4.00–5.00 18 39.2%

Upper Medium 3.50–3.99 7 15.2%

Medium 3.00–3.49 13 28.2%

Low < 3.00 8 17.4%

The results of the third stage can be summarized

as follows: 18 (39.2%) out of 46 students demon-

strated high level of motivation, 7 (15.2%) had upper-

medium motivation level, 13 students (28.2%) of

medium motivation level and 8 (17.4%) – low mo-

tivation level.

The second case discussed here is based on ‘Auti-

Sim’ and ‘Prism’ – serious video games for Teach-

ers, Psychologists and Social Workers trained for in-

clusive education. The idea to use video games in

their study programmes is grounded in the assump-

tions that educational and entertaining games are cen-

tral to a child’s social development because, for ex-

ample, they allow the child to form independent rela-

tionships with peers (Piaget, 1997). Many researchers

have recognised that the development of gaming skills

and using games to engage people with autism can

be helpful. If we compare digital and analog games,

digital games have several advantages over analog

games, namely, in-game results’ tracking, easier cus-

tomisation, better visual interaction, which can be es-

pecially important for people with autism (Atherton

and Cross, 2021).

‘Auti-Sim’ game attempts to simulate the experi-

ence of a child with autism, presenting an experience

of auditory hypersensitivity on a school playground.

The player walks around a school playground, full of

talking children. As they approach the children, the

noise level increases, creating a total audio distortion.

This makes it quite difficult to stay around the other

children for an extended period of time. As a result,

the player spends most of their time at the edges of

the playground, isolated from the rest of the world.

The silence in the game is as powerful as the sound

(Adev123 @TaylanK, 2013). Figure 4 gives under-

standing of this game’s aesthetics and the atmosphere

the players submerge in.

‘Prism’ game attempts to help neurotypical chil-

dren aged 8 to 10 understand their peers who have

autism. It is a game for the children to play, paired

with a discussion framework. It is a tool to help a

generation of children grow up with increased aware-

ness and understanding for their autistic peers (Zhu

et al., 2018). The unique graphics of the game is pre-

sented in figure 5.

Figure 4: Auti-Sim game (Adev123 @TaylanK, 2013).

Figure 5: Prism game (Zhu et al., 2018).

The games were used within the framework of

the University Social and Psychological Service (Al-

fred Nobel University, Dnipro) and the meetings of an

educational and scientific student group ‘Fundamen-

tals of Support for Children with Special Needs and

their Families for Pre-Service Specialists’ Training in

the Socionomic Sphere’. Here, the variety of teach-

ing methods to develop students’ theoretical knowl-

edge and practical skills are used: starting from a

review and analysis of documentary mini-films and

educational-scientific films of the researched prob-

lem; psychoanalysis of blogs, websites, educational

portals, groups on social networks that are social

workers, social educators, psychologists, working

with families raising children with special needs, end-

ing with game therapeutic programmes designed by

foreign scholars and practitioners, in particular, joint

puzzle games Nintendo Wii, ADDventurous Rhyth-

mic planet, social robot (KASPAR); Daisy, ECHOES,

Pico’s Adventure, Let’s Face It (LFI), Go-Go Games

(Atherton and Cross, 2021). A separate educational

and methodical seminar was organised to experiment

with ‘Auti-Sim’ and ‘Prism’ games and to discuss

their potential to develop communication skills, emo-

tional recognition, formation of relationships with

Computer-Mediated Communication and Gamification as Principal Characteristics of Sustainable Higher Education

523

peers. At the end of the seminar, a feedback form was

distributed with the questions related to the experi-

ence of the participants with the video games and their

attitude towards this tool. Multiple choice/unlimited

choice questions were prepared, among which there

were the following:

1) How would you describe your experience with

two video games?

2) How would you describe your feelings about two

video games?

3) Do you think that through video games there is an

opportunity to develop (a set of skills and quali-

ties)?

4) What benefits can video games have as an educa-

tional and therapeutical activity?

5) How do you rate the experience of video games as

an activity in a class?

6) How prepared are you to use video games in your

work?

18 participants of the seminar were asked. The

generalised statistics we got help us understand that

the participants’ experience with video games is a

new one and is perceived as a tool that helps find

out something new (44%); 36%% of the respon-

dents marked game-play experience as a positive one;

16% answered that they were emotionally involved;

it’s motivating – (64%). As for the attitude of the

participants to the video games: they help organise

teamwork – (64%); they help develop useful skills –

(44%); they motivate to learn – (64%); they can en-

gage – (44%); they develop independent learning –

(48%); they develop skills of understanding – (72%).

As for the readiness to use video games: 60% an-

swered that they would like to use them but need more

information on how to use; 20% feel confident; 16%

will use the material that they are familiar with and

are used to; 4% answered that it is risky.

Among the obstacles to use video games in their

practice, the respondents named the absence of spe-

cific knowledge – (68%); low level of digital compe-

tence – (48%); low level of equipment and Internet

connection – (48%); some doubts as for the possible

efficiency of video games as an instructional tool –

(32%).

3.4 Stage Four

The task for the fourth stage was to compare the re-

sults obtained in the present study with those that

we got earlier at Prydniprovska State Academy of

Civil Engineering and Architecture, the Department

of Foreign Languages during March-May, 2020 and

connected with the measurement of the e-learning

courses’ design efficiency. In both cases, the IMMS

instrument was used. Figure 6 represents the compar-

ative results of two studies.

Figure 6: New and old data comparison.

The results of the fourth stage reflect the com-

parative new and earlier received statistics, where we

may see a significant increase in students’ motivation

when the serious video game ‘GloBall Manager’ was

used – 39.2% of High Level in a new study against

8.7% received earlier. At the same time, there is a de-

crease of Upper Medium and Medium Levels’ data,

which is logical as there is an increase of High Level

figures. Interesting enough is the fact that the Low

Level data from both studies coincide, i.e., 8 students

of 46 demonstrated it in the new research and 4 out of

27 in the old one, which gives us 17.4%. We would

describe the new generalised data as the demonstra-

tion of ‘positive disposition’ of students towards the

e-learning material (with an integrated video game)

whereas the previous research results gave us ‘satis-

factory disposition’ to the e-learning courses. This

difference can be explained by a thorough consider-

ation of SVGs’ integration peculiarities that resulted

in better-structured material that students interacted

with, better contextualisation of the material, the abil-

ity of a video game to arise curiosity, present a safe

environment for experimentation, relevant study con-

tent. Also, we would mention a homogeneity of the

course (as there was one instructor and one course

was measured) among the factors that contributed to

students’ motivation increase. In the earlier work, dif-

ferent courses with different instructors and different

syllabuses were evaluated.

4 CONCLUSIONS AND

PROSPECTS FOR FURTHER

RESEARCH

Digimodernism and videoludification of the society

are visible through the gamification process applied

AET 2021 - Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

524

to education, labour, business, therapy, social rela-

tionships. Virtual reality, augmented reality, social

networking platforms (Twitter, Facebook, Instagram,

etc.) are the key contributors to the complex con-

temporary social and cultural transformations (Muriel

and Crawford, 2018). Nowadays, a playful approach

to teaching and learning is seen as effective in moti-

vating and improving students’ engagement, promot-

ing creative thinking towards learning, and develop-

ing multi-disciplinary learning approaches. More-

over, ‘play’ is considered to be a powerful learning

process for adults in higher education, as it is em-

bedded in a constructivist theory of learning, and is

based on experience and reflection as constitute parts

of the learning process (Rice, 2009). Therewith, ICTs

(information communication technologies), AI (ar-

tificial intelligence) and the digitalisation of educa-

tion, including higher education, are now viewed as

indispensable elements of the learning process, and

computer-mediated communication and gamification

as the structural components of sustainable higher ed-

ucation.

In the present work, we undertook the tasks of

overviewing the computer-mediated communication

(CMC) modes and means that have become the pri-

mary channel of communication in the context of

COVID lockdown and after-pandemic period; we dis-

cussed gamification, SVGs, and game-based learning

as a part of contemporary educational reality; pre-

sented the results of the courses’ efficiency measure-

ment through the application of ‘The Instructional

Materials Motivation (IMMS)’ survey by (Keller,

2010a) and the feedback form developed by the re-

search team.

Distance learning and its later version – e-learning

that expands the educational process by giving ac-

cess to knowledge from anywhere, at any time, at any

speed and is backed up by the CMC, the latest mul-

timedia technologies and the Internet, should be ap-

plied with the organisational culture analysis in mind.

We maintain that the model of ‘any time’, ‘any place’,

‘any way’, ‘any speed’ needs to be supplemented by

a cultural component under which we mean the cul-

ture of a particular institution (European Information

Society, 2003). This, in turn, implies the need to un-

derstand what e-learning modes are used by an organ-

isation, measure their effectiveness, and suggest the

most efficient model and the ways of e-learning inte-

gration into a particular HEI according to its needs’

analysis.

The most popular video-conferencing platforms

and tools chosen by the teachers of the department

and discussed in the earlier article (Tokarieva et al.,

2021) were Viber (with its video-conferencing fea-

ture), Skype, and Zoom, while Google Hangouts and

Discord with the same video-conferencing feature

were found less popular. Social networking apps ac-

tively used by the faculty were Telegram, Viber; e-

mail service was used as the asynchronous mode of

correspondence with students.

Skype was chosen by many because of the un-

limited number of video chat participants, the ease

of operation on the screen, the inclusion of such ac-

tivities as speaking, reading, and, partially, writing.

Google Hangouts application – because of a ‘Share

Screen’ feature that lets students see what the instruc-

tor demonstrates on the monitor, a ‘Chat History’ fea-

ture – because it records the number of people attend-

ing each class, Google Classroom – as it lets post as-

signments and set up the deadline, evaluate students’

works according to a variety of evaluation scales.

The most debatable was the Zoom platform as,

on the one hand, it does not limit the number of the

participants, is quite easy in operation, has a session

recording feature, an instructor’s screen demonstra-

tion, a whiteboard to write comments, a group chat

feature, a waiting room (to prevent unregistered par-

ticipants join the conference), a conference room –

to split students into separate mini-groups. At the

same time, such a phenomenon as ‘Zoom fatigue’

was marked by teachers, which can be partially ex-

plained by the presence of many people at a time on

the screen, the need to monitor our non-verbal lan-

guage as instructors, to shift to teacher-centricity and

one-way communication. It is also worth mentioning

here that back in March-May 2020 Google Meet was

not as popular an application as it is now.

With the reference to the students’ feedback from

the distance work during the quarantine – ‘depen-

dence on technical means’ was named as the main

challenge, followed by the poor quality of the In-

ternet, problems with self-organisation, the number

of tasks, restriction on exercising practical skills.

Though the experimental sample was quite small and

limited to thirty instructors and twenty-three students,

we maintain that the experience of our department

at the time of the quarantine due to the COVID-19

situation still highlights the current e-learning situa-

tion in our HEIs, reveals several challenges and needs,

helps layout further strategies to support fluid, holis-

tic, seamless, pervasive, personalised education opti-

mised by technology.

Digital pedagogy, gamification, game-based

learning and serious video games based on CMC

and nowadays, mobile technology are becoming

principal parts of contemporary education. They

are capable to enhance learning through challenge,

exploration, interaction, reflection, ‘positive failure’,

Computer-Mediated Communication and Gamification as Principal Characteristics of Sustainable Higher Education

525

adaptability to a particular player’s decision-making

level, etc. Practical work, based on two video games,

that is described in task three proved positive results

(e.g. students’ increased motivation) and positive

attitude of the pre-service training students in the

socioeconomic sphere towards video games as a

way of instruction. We would explain this ‘posi-

tive disposition’ of students by a better-structured

material that students interacted with, better con-

textualisation of the material, the ability of a video

game to arise curiosity, present a safe environment

for experimentation and relevant study content.

Video games were also described as capable to de-

velop skills of team-working, problem-solving, criti-

cal thinking; to enhance self-guided learning skills.

At the same time, a strong need for pedagogic training

that may empower teachers with the required knowl-

edge and skills about gamified learning applications,

educational digital games and digital competencies

development was identified. This confirmed the ear-

lier conclusions about the need to increase the level

of digital and pedagogical skills of HEIs faculty; to

further develop their didactic skills in mastering new

approaches to academic courses’ material design in e-

learning format; to encourage the culture of coopera-

tion and sharing, as well as to experience a wide range

of applications, digital tools, and services that sup-

port the process of education; the development of an

educational content to be accessed by students at any

time, from any place, from any computer, the increase

of students’ digital literacies (Tokarieva et al., 2021).

All of the above brings us to the conclusion about

the topicality of what information technology offers –

the options for reorganising and refining distance and

e-learning. But the new vision of distance and e-

learning, gamification of educational process and seri-

ous video games as one more variation of CMC must

drive our decisions about the use of technology, not

vice versa. Therefore, the need to develop teacher-

training programs to help educators understand, de-

sign, evaluate and apply CMC and gamified learning

applications is set up as the vector of future work.

5 LIMITATIONS

Our present research holds certain limitations as for

the generalisability of its results. Among them are the

size of the sample. The obtained results were com-

pared with a similar survey, which makes the compar-

ison results as the first approximation. There is also a

need for further tests of the questionnaire’s reliability

and validity.

REFERENCES

Abrams, Z. (2006). From the theory to practice: In-

tercultural CMC in the L2 Classroom. In Ducate,

L. and Arnold, N., editors, Calling on CALL: From

Theory and Research to New Dimensions in Foreign

Language Teaching, volume 5 of Monograph Series,

pages 181–210. CALICO.

Adev123 @TaylanK (2013). Auti-Sim. https://gamejolt.

com/games/auti-sim/12761.

Alkind Taylor, A.-S. (2014). Facilitation Matters: A Frame-

work for Instructor-Led Serious Gaming. PhD the-

sis, University of Sk

¨

ovde. https://www.diva-portal.

org/smash/get/diva2:745056/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

Andreev, A. A. (2013). E-learning and distance learn-

ing technologies. Open education, 5:40–46. https:

//openedu.rea.ru/jour/article/download/218/220.

Androutsopoulos, J. (2006). Introduction: Soci-

olinguistics and computer-mediated communica-

tion. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 10(4):419–

438. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/

j.1467-9841.2006.00286.x.

Arnab, S., Lim, T., Carvalho, M. B., Bellotti, F.,

de Freitas, S., Louchart, S., Suttie, N., Berta,

R., and De Gloria, A. (2015). Mapping learn-

ing and game mechanics for serious games anal-

ysis. British Journal of Educational Technology,

46(2):391–411. https://bera-journals.onlinelibrary.

wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/bjet.12113.

Artemyeva, O., Makeeva, M., and Milbrud, R. (2005).

Methodology of Organising Specialist Training Based

on Intercultural Communication. TSTU Publishing

House, Taganrog.

Atherton, G. and Cross, L. (2021). The Use of Analog and

Digital Games for Autism Interventions. Frontiers in

Psychology, 12. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/

10.3389/fpsyg.2021.669734.

Barker, K. (1999). Quality Guidelines for Technology-

Assisted Distance Education. Technical report, Fu-

turEd Consulting Education Futurists. http://futured.

com/pdf/distance.pdf.

Baxter, R. J., Holderness, D. Kip, J., and Wood, D. A.

(2017). The Effects of Gamification on Corporate

Compliance Training: A Partial Replication and Field

Study of True Office Anti-Corruption Training Pro-

grams. Journal of Forensic Accounting Research,

2(1):A20–A30. https://doi.org/10.2308/jfar-51725.

Beauvois, M. (1997). Write to Speak: The Effects of

Electronic Communication on the Oral Achievement

of Fourth Semester French Students. In Muyskens,

J. A., editor, New Ways of Learning and Teaching: Fo-

cus on Technology and Foreign Language Education,

pages 102–124. Heinle & Heinle Publishers, Boston.

http://hdl.handle.net/10125/69531.

Becker, K. (2017). Choosing and Using Digital Games

in the Classroom. Advances in Game-Based

Learning. Springer Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/

978-3-319-12223-6.

Bordia, P. (1997). Face-to-Face Versus Computer-Mediated

Communication: A Synthesis of the Experimental

AET 2021 - Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

526

Literature. The Journal of Business Communica-

tion (1973), 34(1):99–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/

002194369703400106.

Bramble, W. J. and Panda, S., editors (2008). Economics of

Distance and Online Learning: Theory, Practice and

Research. Routledge, New York.

Chickering, A. W. and Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven Prin-

ciples For Good Practice in Undergraduate Education.

AAHE Bulletin, 39(7):3–7. https://www.lonestar.edu/

multimedia/sevenprinciples.pdf.

Dabbagh, N. and Bannan-Ritland, B. (2005). Online Learn-

ing: Concepts, Strategies, and Application. Pearson,

Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Dahlberg, L. (2001). Computer-Mediated Communication

and the Public Sphere: a Critical Analysis. Journal

of Computer-Mediated Communication, 7(1). https:

//doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2001.tb00137.x.

Dalziel, C., editor (1998). New Connections: A Guide

to Distance Education. Instructional Telecom-

munications Council, Washington, D.C., 2 edi-

tion. http://web.archive.org/web/20000126105830/

https://www.itcnetwork.org/definition.htm.

Deterding, S. (2012). Gamification: Designing for Moti-

vation. Interactions, 19(4):14–17. https://doi.org/10.

1145/2212877.2212883.

Editorial Team (2013). What is GBL (Game-Based

Learning)? https://www.edtechreview.in/dictionary/

what-is-game-based-learning.

European Information Society (2003). eLearning: Better

eLearning for Europe. https://www.lu.lv/materiali/

biblioteka/es/pilnieteksti/izglitiba/eLearning%20-%

20Better%20eLearning%20for%20Europe.pdf.

Fedorenko, E. H., Velychko, V. Y., Stopkin, A. V., Chorna,

A. V., and Soloviev, V. N. (2019). Informatization

of education as a pledge of the existence and devel-

opment of a modern higher education. CTE Work-

shop Proceedings, 6:20–32. https://doi.org/10.55056/

cte.366.

Hardaker, C. (2010). Trolling in asynchronous computer-

mediated communication: From user discussions to

academic definitions. Journal of Politeness Research,

6(2):215–242. https://doi.org/10.1515/jplr.2010.011.

Huang, B. and Hew, K. F. (2016). Measuring Learners’

Motivation Level in Massive Open Online Courses.

International Journal of Information and Education

Technology, 6(10):759–764. https://doi.org/10.7763/

IJIET.2016.V6.788.

Huotari, K. and Hamari, J. (2012). Defining Gamifica-

tion: A Service Marketing Perspective. In Proceed-

ing of the 16th International Academic MindTrek Con-

ference, MindTrek ’12, page 17–22, New York, NY,

USA. Association for Computing Machinery. https:

//doi.org/10.1145/2393132.2393137.

IHEP (2000). Quality On the Line: Benchmarks

for Success in Internet-Based Distance Ed-

ucation. Technical report, The Institute for

Higher Education Policy, Washington, DC.

https://www.ihep.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/

05/uploads docs pubs qualityontheline.pdf.

Im, J. H. (2006). Development of an E-Education Frame-

work. Online Journal of Distance Learning Adminis-

tration, 9(4). https://www.learntechlib.org/p/193197.

Interactive Software Federation of Europe (2022). Games

in Society.

Joinson, A. N. (2001). Self-disclosure in computer-

mediated communication: The role of self-awareness

and visual anonymity. European Journal of So-

cial Psychology, 31(2):177–192. https://onlinelibrary.

wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ejsp.36.

Joosten, T. (2022). Tanya Joosten, strategic and collabora-

tive leader for innovation. https://tanyajoosten.com/.

Keller, J. and Suzuki, K. (2004). Learner motivation and E-

learning design: A multinationally validated process.

Learning, Media and Technology, 29:229–239. https:

//doi.org/10.1080/1358165042000283084.

Keller, J. M. (2010a). Motivational Design for Learn

ing and Performance: The ARCS Model Approach.

Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/

978-1-4419-1250-3.

Keller, J. M. (2010b). The Instructional Materials Motiva-

tion Survey. https://learninglab.uni-due.de/file/9725/

download?token=71ZAFqWh.

Kirby, A. (2006). The Death of Postmodernism

and Beyond. Philosophy Now, 58:34–

37. https://philosophynow.org/issues/58/

The Death of Postmodernism And Beyond.

Kock, N. (2004). The Psychobiological Model: Towards

a New Theory of Computer-Mediated Communica-

tion Based on Darwinian Evolution. Organization

Science, 15(3):327–348. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.

1040.0071.

Luksha, P., Cubista, J., Laszlo, A., Popovich, M., Ni-

nenko, I., and participants of GEF sessions in 2014-

2017 (2018). Educational Ecosystems for Societal

Transformation. Global Education Futures Report,

Global Educational Futures. https://globaledufutures.

org/educationecosystems.

Marklund, B. B. (2015). Unpacking Digital Game-Based

Learning: The complexities of developing and us-

ing educational games. PhD thesis, University of

Sk

¨

ovde. http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:

891745/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

Marshall, S. (2010). A Quality Framework for Continuous

Improvement of E-learning: The E-learning Maturity

Model. International Journal of E-Learning & Dis-

tance Education / Revue internationale du e-learning

et la formation

`

a distance, 24(1):143–166.

Masoumi, D. and Lindstr

¨

om, B. (2012). Quality in e-

learning: a framework for promoting and assuring

quality in virtual institutions. Journal of Computer

Assisted Learning, 28:27–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/

j.1365-2729.2011.00440.x.

Muriel, D. and Crawford, G. (2018). Video Games As Cul-

ture: Considering the Role and Importance of Video

Games in Contemporary Society. Routledge, London.

https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315622743.

Palloff, R. and Pratt, K. (1999). Building Learning Com-

munities in Cyberspace: Effective Strategies for the

Computer-Mediated Communication and Gamification as Principal Characteristics of Sustainable Higher Education

527

Online Classroom. Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Ed-

ucation. Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Francisco.

Piaget, J. (1997). The Moral Judgment of the Child. Free

Press.

Rice, L. (2009). Playful Learning. Journal for Education

in the Built Environment, 4(2):94–108. https://doi.org/

10.11120/jebe.2009.04020094.

Rice, R. E. (2006). Computer-Mediated Communication

and Organizational Innovation. Journal of Com-

munication, 37(4):65–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.

1460-2466.1987.tb01009.x,.

Shaffer, D. W., Squire, K. R., Halverson, R., and Gee, J. P.

(2005). Video Games and the Future of Learning.

Phi Delta Kappan, 87(2):105–111. https://doi.org/10.

1177/003172170508700205.

Silva, R., Rodrigues, R., and Leal, C. (2018). Academic

Motivation Scale: Development, Application and Val-

idation for Portuguese Accounting and Marketing Un-

dergraduate Students. International Journal of Busi-

ness and Management, 13(11):1–16. https://doi.org/

10.5539/ijbm.v13n11p1.

Supiano, B. (2020). Why is Zoom so exhaust-

ing? https://grad.uic.edu/news-stories/

why-is-zoom-so-exhausting/.

Tokarieva, A. V., Volkova, N. P., Degtyariova, Y. V., and

Bobyr, O. I. (2021). E-learning in the present-day

context: from the experience of foreign languages

department, psacea. Journal of Physics: Confer-

ence Series, 1840:012049. https://doi.org/10.1088/

1742-6596/1840/1/012049.

Tokarieva, A. V., Volkova, N. P., Harkusha, I. V., and

Soloviev, V. N. (2019). Educational digital games:

models and implementation. CTE Workshop Proceed-

ings, 6:74–89. https://doi.org/10.55056/cte.369.

Virtual Campus Lda (2015). Globall Manager.

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=eu.

virtualcampus.globall.

Volery, T. and Lord, D. (2000). Critical success factors

in online education. International Journal of Educa-

tional Management, 14(5):216–223. https://doi.org/

10.1108/09513540010344731.

Walther, J. B. (1996). Computer-Mediated Communica-

tion: Impersonal, Interpersonal, and Hyperpersonal

Interaction. Communication Research, 23(1):3–43.

https://doi.org/10.1177/009365096023001001.

Wouters, P., Nimwegen, C., Oostendorp, H., and Spek, E.

(2013). A Meta-Analysis of the Cognitive and Moti-

vational Effects of Serious Games. Journal of Educa-

tional Psychology, 105:249. https://doi.org/10.1037/

a0031311.

Zemliansky, P. and Wilcox, D., editors (2010). Design

and Implementation of Educational Games: Theoret-

ical and Practical Perspectives. IGI Global. https:

//doi.org/10.4018/978-1-61520-781-7.

Zhu, Y., Wolpow, D., Ramesh, R., Zheng, Y., and Wang,

X. (2018). Prism. https://www.gamesforchange.org/

game/prism/.

AET 2021 - Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

528