Developing Translators’ Soft Skills in a Cloud-Based Environment Using

the Memsource System

Rostyslav O. Tarasenko

1 a

, Svitlana M. Amelina

1 b

, Serhiy O. Semerikov

2,3,4 c

and Liying Shen

1,5 d

1

National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine, 15 Heroiv Oborony Str., Kyiv, 03041,Ukraine

2

Kryvyi Rih State Pedagogical University, 54 Gagarin Ave., Kryvyi Rih, 50086, Ukraine

3

Kryvyi Rih National University, 11 Vitalii Matusevych Str., Kryvyi Rih, 50027, Ukraine

4

Institute for Digitalisation of Education of the NAES of Ukraine, 9 M. Berlynskoho Str., Kyiv, 04060, Ukraine

5

Anhui International Studies University, 2 Fanhua Ave., Hefei, 231201, Anhui, China

Keywords:

Soft Skills, Cloud-Based Learning Environment, Memsource System, Translator.

Abstract:

The paper deals with the possibilities of developing translators’ soft skills in a cloud-based learning envi-

ronment using the Memsource system. The main advantages of Memsource in the educational process are

identified. The main advantages of Memsource in the educational process are identified: accessibility through

the offer of a demo and an academic programme, easy for mastering, the user-friendly interface, a wide func-

tional range. Experimental training of students in groups for translation projects with mastery of the tasks

of team members of different statuses was carried out. Students’ evaluation of the functionality of the Mem-

source system was analysed in terms of learning effectiveness and application in their future professional life.

A list of soft skills improved by students during the experiential learning period was identified: digital skills,

communication skills, teamwork skills, self-monitoring abilities, responsibility, leadership skills.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Statement of the Problem

Today, the arsenal of tools that translators use in their

professional work is quite diverse. It includes not

only automated and machine translation systems, ter-

minology management systems and translation mem-

ory systems, but also a range of service programmes

and translation support information sources. There

is a clear tendency to focus not only on the use of

information support predominantly from Internet re-

sources, but also on the use of cloud services that du-

plicate traditional desktop systems and are accessed

via network resources. This leads to the view that to-

day it is not advisable to concentrate on mastering a

single software product or information resource, but

rather to form a cloud-oriented environment as a sys-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6258-2921

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6008-3122

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0789-0272

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7421-2899

tem of necessary tools and resources to carry out the

full range of operations for translation projects. At

the same time, an important aspect of professional

training of translators is the development of their soft

skills when working in a cloud-oriented environment,

as this type of activity requires the ability to cooper-

ate, lead or follow a leader, and meet deadlines for

tasks or individual phases of a task. It is common for

large tasks to be carried out by a team of translators in

translation projects. This requires clear coordination

of the work of individual project participants, moni-

toring of task progress, self-monitoring of deadlines

by translators (time management), digital skills in a

cloud-oriented environment, and remote communica-

tion skills.

1.2 The Purpose of the Article

The purpose of this paper is to explore the possibility

of developing the soft skills of prospective translators

when completing training projects in a cloud-based

environment using the Memsource system.

Tarasenko, R., Amelina, S., Semerikov, S. and Shen, L.

Developing Translators’ Soft Skills in a Cloud-Based Environment Using the Memsource System.

DOI: 10.5220/0012066500003431

In Proceedings of the 2nd Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology (AET 2021), pages 617-628

ISBN: 978-989-758-662-0

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

617

1.3 Literature Review

The popularity of cloud technologies is growing

rapidly in all fields of application. The translation

industry is no exception. Researchers in the field of

language technology attribute the increasing use of

cloud systems to their greater independence from op-

erating systems and locations, easier conditions for

collaboration, savings through operation without in-

stallation, and the offer of flexible licensing models

(Imhof, 2014).

The last two decades have seen a dynamic of

scholarly attitudes that correlate with the development

of information technologies. In particular, whereas

previously only the main benefits of information tech-

nology learning for translators were considered, with

suggestions for rethinking the teaching of translation

(Bowker, 2002), the translation process as a whole

is now understood as an interaction between trans-

lator and computer (Bundgaard et al., 2016; Chan,

2015; O’Brien, 2012; Tarasenko and Amelina, 2020;

Tarasenko et al., 2020). The proliferation of informa-

tion technologies in the translation industry, in partic-

ular cloud-based technologies, is illustrated, for ex-

ample, by data from TAUS, a think tank whose mis-

sion is to automate and innovate in the translation in-

dustry (Choudhury and McConnell, 2013).

According to Gamb

´

ın (Gamb

´

ın, 2014), one of the

most important changes over the last ten years has

been the proliferation of solutions with a clear trend

towards cloud solutions. The use of cloud technolo-

gies in translation, according to the scholar, promotes

competition, which in turn means lower and more

flexible prices. This is particularly relevant for the ac-

tivities of small groups of translators who do not have

the infrastructure and finances that large corporations

do, but thanks to cloud platforms, they will be able to

compete with them in some way. At the same time,

Gamb

´

ın (Gamb

´

ın, 2014) notes that the level of tech-

nologies on offer today is very different, but that high-

quality solutions are becoming more affordable over

time than they used to be. DePalma and Sargent (De-

Palma and Sargent, 2013) holds the same view and

argues that the field of translation services will un-

doubtedly move to cloud-based solutions in the near

future. Practitioners say the most popular translation

management systems (TMS) on the market include

SDL WorldServer, Memsource, GlobalLink, Across

(Choudhury and McConnell, 2013; Tarasenko et al.,

2020; Ultimate Languages, 2018). The availability of

a choice of cloud offerings is emphasised by Muegge

(Muegge, 2013), noting their wide range, e.g. Word-

fast Anywhere, Lionbridge Translation Workspace,

Memsource Cloud, Wordbee, XMT Cloud. Based on

the experience of teaching a master’s course for trans-

lators, Muegge (Muegge, 2013) concludes that cloud-

based systems are easy to use, because all a translator

needs is an Internet connection and a login. Since the

“heavy” processes (segmentation, TM and glossary

search, etc.) in all cloud-based systems take place on

the server, there are no multi-step installation proce-

dures required as for desktop systems.

As we can see, from a scholarly perspective, the

professional activity of translators is rapidly shifting

towards working in a cloud-oriented environment and

is carried out through the execution of a translation

project by a team of translators. This form of work

assumes that translators have a number of soft skills,

primarily related to organisational and communica-

tive aspects. Soft skills are classified as “a broad set

of skills, competencies, behaviors, attitudes, and per-

sonal qualities that enable people to effectively nav-

igate their environment, work well with others, per-

form well, and achieve their goals. These skills are

broadly applicable and complement other skills such

as technical, vocational, and academic skills” (Lipp-

man et al., 2015). Recently, employers have been fo-

cusing on these skills, stating that university graduates

lack them (ManpowerGroup, 2013).

Employers consider soft skills to help profession-

als succeed in the labour market as: social skills, com-

munication skills, higher-order thinking skills (prob-

lem solving, critical thinking and decision-making),

self-control skills and a positive self-concept (Lipp-

man et al., 2015). In the context of our study, we

should focus on some of these skills. Social skills

are understood by scholars as the ability to get along

with other people, to avoid conflicts and to find ways

to resolve them when they arise. For the translators

involved in the project, the ability to work as part of

a team and to cooperate with other team members in

a conflict-free manner are important. From this per-

spective, the communication skills of project partici-

pants are extremely important, which can be realised

verbally or in writing, in particular in the form of

communication within the project.

The broadest coverage of the list of soft skills nec-

essary for the successful career of young profession-

als is presented, in our view, in the U.S. Secretariat’s

detailed analysis of the U.S. Commission on Achiev-

ing Required Skills (SCANS). The thinking skills

cover creative thinking, decision making, problem

solving, reasoning, and the ability to learn. SCANS

specifies that personal qualities include responsibility,

self-esteem, sociability, self-management, integrity,

and honesty. SCANS identifies five groups of work-

place competencies: the ability to allocate resources

(time, money, facilities), interpersonal skills (such as

AET 2021 - Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

618

teamwork, teaching others, leadership), the ability to

acquire and to use information, the ability to under-

stand systems, and the ability to work well with tech-

nology (Kautz et al., 2014).

Given that the vast majority of publications on the

subject of soft skills development also point to the im-

portance of digital skills for professionals, we think it

is worth considering the possibility of developing the

soft skills of prospective translators precisely in the

cloud-oriented environment in which they will have

to work in the future.

2 RESULT AND DISCUSSION

2.1 Memsource as a Key Component of

a Cloud-Based Environment in

Which to Develop Translators’ Soft

Skills

The Memsource cloud-based system for mastering

the principles of translation projects is a good choice

as the basic component of a cloud-based training en-

vironment for translators. The following arguments

can support this decision:

• although this CAT system offers proprietary soft-

ware, Memsource provides the opportunity to take

advantage of free software demos for 30 days,

subject to registration and compliance with the

relevant conditions,

• the software interface is clear and easy to master,

• the demo versions are functional on all the main

operations of translation projects,

• ability to integrate with other cloud-based transla-

tion tools,

• there is a wide choice of interface languages dur-

ing the registration process,

• the possibility of supplementing the functional-

ity of the system by connecting terminology re-

sources via terminology and translation memory

databases.

An equally important argument in favour of us-

ing Memsource as the base element of a cloud-based

system is its widespread use and study in the world’s

leading universities training translators (figure 1).

2.2 Selection of Memsource Version for

Creating a Cloud-Oriented

Environment From the Perspective

of Translators’ Soft Skills

Development

The official Memsource website offers different ver-

sions of the programme, structured according to need

and the level of work to be performed. In partic-

ular, offers are presented in different packages: for

freelancers, small translation structures and powerful

translation structures in four separate packages: Team

Start, Team, Ultimate, and Enterprise.

Each of these packages can be used to form

a cloud-based environment for translator training.

However, we have chosen Team to model, as closely

as possible, the organisation of the workflow and the

automation of its stages with a multi-level manage-

ment structure and control of the conditions of trans-

lation services according to the ISO 17100:2015 stan-

dard.

Of course, its potential for soft skills development

in prospective translators also played an important

role in the choice of the Team package. Having anal-

ysed the functional aspects of the package, we con-

cluded that by using it, students can develop a number

of soft skills necessary for their future professional

activities, namely:

• the ability to work in a team, fulfilling a specific

role assigned by the project administrator,

• the ability to communicate with other project par-

ticipants based on the needs of the project,

• the ability to exercise self-monitoring in the per-

formance of tasks within a translation project.

Another important condition for using this pack-

age was that we received an annual licence to use it

under the academic programme (figure 2).

This is necessary, given that building a cloud-

based environment based on this Memsource package

is a painstaking and time-consuming job, and its use

should provide training for students throughout the

academic year, which unfortunately cannot be fully

realised using the demo.

2.3 Developing Teamwork Skills in

Implementing Translation Projects

in a Cloud-Based Environment

Using the Team Version

As mentioned earlier, the Team package is best suited

to meet the needs of translation structures operating

Developing Translators’ Soft Skills in a Cloud-Based Environment Using the Memsource System

619

Figure 1: Geography of university use of the Memsource cloud system.

Figure 2: Marking on the Memsource cloud system website that the licence has been granted.

under a defined management hierarchy and practis-

ing a team approach to delivering translation projects.

Mastering the Team suite will enable students to

acquire skills in the administration of translation

projects, management of human resources, terminol-

ogy management, automated task preparation and dis-

tribution, analytical evaluation of project tasks, and

performance evaluation of each individual participant

in project implementation.

In order to use the Team package, a number of

additional steps need to be taken to form a team of

translators, managers and task distribution.

As the Team package allows the organisation of a

hierarchical management system, a cadre of perform-

ers was formed from the students and given different

statuses. In particular, the system provides four differ-

ent statuses that can be given to enrolled performers,

namely: “Administrator”, “Project Manager”, “Lin-

guist” and “Guest”. Depending on their status, each

performer had different opportunities and rights of ac-

cess to carry out certain actions.

The administrator provided by far the highest level

of functionality. In particular, he or she could create

translation projects; enroll new performers; set and

change performer statuses; assign tasks to performers

within a project; monitor the status of each individual

AET 2021 - Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

620

performer and the whole project team; and create, edit

and populate translation memories and terminology

databases.

The immediate work of the administrator, which

started at the applicant enrollment stage, was the pro-

cess of forming the project team, giving them appro-

priate statuses and distributing tasks among the par-

ticipants. This enrollment could be done in two ways.

One is to fill in the relevant form for each applicant

and the other is to enroll applicants comprehensively

by importing data from a pre-filled table in XLSX for-

mat (figure 3).

Once Memsource has enlisted people with differ-

ent roles in translation projects, it is necessary to form

teams of performers for individually defined projects.

In this case, a project manager is selected, who in

turn distributes tasks between translators within the

project, either alone or together with the adminis-

trator. Of course, all the steps involved in creating

projects and allocating tasks to projects need to be

completed before the tasks can be allocated.

In order to master other roles as participants in a

translation project, students could be given the sta-

tuses of “Project Manager” and “Linguist”, which

changed over the course of their work on different

projects.

Students with Project Manager status mastered

management skills. The range of functionality of the

system manager depended largely on the settings set

by the administrator. One of the main functions of

the manager was to work out the distribution of tasks

between the projects implementers (figure 4).

However, it should be noted that by activating all

the possible options for manager status, the range of

his capabilities will come close to those of an admin-

istrator. If partial options are activated, his/her powers

will usually be limited to access to a specific project

only, managing the executors of that project as a team

of translators (linguists), managing translation memo-

ries and terminology databases. By observing the ac-

tivities of the students in the implementation of train-

ing translation projects, we have in some cases raised

the status of project participants to managerial status,

giving them the opportunity to exercise their own abil-

ities at this level.

The settings established for this status also al-

lowed for the creation and maintenance of terminol-

ogy and translation memory bases within a single

project, the management of its executing team, and

the monitoring of the project’s progress status (fig-

ure 5).

The project administrator can obtain information

on the level of implementation of the individual tasks

within a certain project, in particular the number of

translated and confirmed segments as a percentage,

the status of the task as a whole, the name of the per-

former, etc. (figure 6). In addition to this information

it is possible to perform various actions on the anal-

ysis of individual tasks. The use of these functions

enables the development of critical thinking skills in

the performers of the project. In particular, it is possi-

ble to see statistical indicators relating directly to the

translation aspects of a particular task. In the structure

of the window, a separate block called “Analysis” will

be formed under the list of tasks. In this block, entries

for the analysis of a particular task will be placed in

separate lines.

To perform the analysis, it is possible to directly

activate a table with a number of indicators (figure 7)

related to the translation of the task for which the anal-

ysis is performed. These indicators will provide in-

formation on the total number of segments into which

the system automatically divides the whole document,

the number of pages in it, the number of words and

characters. An important aspect of such an analyt-

ical table is also the information about the number

of matches of these indicators against the transla-

tion memory, if such a database is connected to the

project. In this case, the table contains detailed infor-

mation even in terms of percentage matches between

the words or segments present in the text and the cor-

responding words or segments in the translation mem-

ory database.

It is worth noting that the project participants, who

were given the roles of administrator and manager,

were able to demonstrate and develop their leadership

skills through these roles. They were given full re-

sponsibility for the implementation of the project, so

they coordinated the work of the entire team of trans-

lators.

The vast majority of the students in each individ-

ual project had the status of “Linguist”. They were

engaged directly to carry out the translation by per-

forming a specific task. Students who acted as editors

also held this status. The students who acted as edi-

tors also had this status. There can be any number of

such performers in a project, but each of them must

be assigned a separate task to perform. Both the ad-

ministrator and the project manager can define such a

task and monitor its progress. A translator with Lin-

guist status also has a range of settings, which can re-

strict or expand the range of possible actions. These

settings are usually made by the project manager. In

particular, the settings can give the translator access to

edit entries in the terminology database, edit entries in

the translation memory, use machine translation, etc.

Before the translation started, the manager en-

sured that a specially created terminology and trans-

Developing Translators’ Soft Skills in a Cloud-Based Environment Using the Memsource System

621

Figure 3: Enrollment of participants by the administrator and assignment of their respective roles.

Figure 4: Distribution of tasks between project implementers in the Memsource system.

lation memory database was connected to the project.

This was done with the aim of having students with

Linguist status practise the overwhelming number of

possible features implemented in the Memsource sys-

tem. In particular, provided the original segmented

text was presented in a special window, the student

was able to fill in variants of the target text in differ-

ent ways (figure 8). These included: writing the target

text manually from the keyboard; substituting a sug-

gested translation variant based on the translation re-

sults in the selected machine translation system; sub-

stituting a suggested translation variant based on the

results of a match with a segment in the connected

translation memory, selecting the corresponding indi-

vidual term suggested from the terminology database.

2.4 Developing Self-Monitoring Skills

Based on Translation Quality

Management in a Cloud-Based

Environment Using the Memsource

System

The large volume of material cannot be translated by

using even highly qualified translators without the lat-

est information technology-based tools. Experience

has shown that the traditional approach to translating

large volumes of documentation in the education sec-

tor by a team of translators has a number of negative

consequences:

• low productivity due to the need for each transla-

tor to translate the same terminology several times

in isolation,

• lack of uniform terminology used by each trans-

lator in a particular academic and scientific field,

which leads to difficulty in understanding the con-

tent of the translated text by users,

• the difficulty of coordinating the activities of a

group of translators,

• the difficulty of coordinating the activities of a

group of translators,

• a high degree of dependence of the success-

ful completion of a translation on the individual

translator as the individual owner of the terminol-

ogy resource.

With this in mind, it is advisable to train trans-

lators with the understanding that their future profes-

sional activities will involve them mainly in teamwork

in translation projects with the obligatory use of the

latest information technologies. Cloud-based systems

are promising in this regard and have a number of ad-

vantages, as already mentioned in this paper.

The execution of translation projects enables a

team of translators to coordinate their work, distribute

tasks and get results, thereby achieving the goal of

translating large amounts of textual material.

AET 2021 - Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

622

Figure 5: General monitoring of the status of projects and tasks in the Memsource system.

Figure 6: Monitoring the level of implementation of the individual tasks within the project.

The execution of translation projects enables a

team of translators to coordinate their work, distribute

tasks and get results, thus achieving the goal of trans-

lating a large volume of textual material.

At the same time, however, there is also the is-

sue of ensuring the quality of the translated material,

since losses in translation quality can be due to var-

ious types of errors, ranging from minor ones that

do not make the target text difficult to understand

to important ones that can lead to future misunder-

standings or even losses due to incorrect or inaccurate

translation. Particular attention is required to ensure

that translators working on the same project use con-

sistent terminology in order to avoid disagreements

when translating parts of the same text.

In this aspect, it is valuable for training future

translators to learn to apply the QA (Quality Assur-

ance) management processes built into Memsource

after the translation has been completed, or even in

the intermediate stages of completion. This gives the

translator a powerful tool to see what spelling mis-

takes have been made, identify missing elements in

the translated segment in relation to the source seg-

ment, and ensure terminology consistency based on a

connected terminology database, and so on (figures 9,

10).

In order to successfully master the QA processes,

students learned a sequence of actions, namely:

• activate the tab of the same name in the window,

which, by default, displays the suggested transla-

tion options. In this case, a list of errors detected

by the system will be displayed with the number

of the segment in which they occurred,

• make the necessary changes to the target text in

those segments where the system has detected er-

rors.

Once the translation of the file had been com-

pleted, the students’ next steps were to receive the

translation results as a file in the format in which the

original file was also posted, or to submit the results

to the editor for review.

In the first case, they activated the browser tab

with the translation project window, highlighted the

task whose translation results were to be received as a

file and selected the finished file for downloading via

the context menu. Because of these actions, the stu-

dent received on their own computer a downloaded

Developing Translators’ Soft Skills in a Cloud-Based Environment Using the Memsource System

623

Figure 7: Table with indicators on the translation of the individual task.

Figure 8: Example of translation in the Memsource system.

file with the target text, created based on the results of

the translation and quality assurance activities.

In the second case, when editing is necessary be-

fore uploading the final translation results, students

are reminded to select the DOCX option in the con-

text menu. This will allow uploading the translation

results by means of a bilingual text whose segments

are placed in a table.

This option is useful if the person editing the

translated text prefers to work with a text file in a text

editor. It is also possible to check spelling when work-

ing with such a file, using the appropriate features of

a text editor.

In general, in terms of translation quality assur-

ance, a cloud-based translation memory system is bet-

ter suited to cooperation between distributed teams of

translators. By storing the linguistic resources (TM,

TB, and bilingual MXLIFF) on one central server,

translators can easily access the resources together

and simultaneously. This allows already translated

segments and created terms to be shared during the

translation process. In addition, the workflow feature

allows different project participants, such as transla-

tors, editors and proofreaders, to work on a docu-

ment simultaneously, which can significantly reduce

the turnaround time of a translation project.

3 ANALYSIS OF THE

FEASIBILITY OF USING

MEMSOURCE TO DEVELOP

TRANSLATORS’ SOFT SKILLS

WITHIN A CLOUD-BASED

ENVIRONMENT

In order to determine the feasibility of using Mem-

source in translator training as the main component of

a cloud-based environment that can be used to form

and develop soft skills, we asked students who had

gained experience with this cloud-based automated

translation system while studying “Information Tech-

nology in Translation Projects” (67 people) first to

rate the usefulness of individual functions of the sys-

tem on a 5-point system, and second to identify the

AET 2021 - Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

624

Figure 9: Checking spelling in Memsource.

Figure 10: Checking the correctness of the translation by comparing segments of the source and target texts.

soft skills that they were able to improve when carry-

ing out translation projects using the Memsource sys-

tem.

The list of functions include: source text review

during translation, display of full matches, display

of fuzzy matches, integration with the MT system,

merge/divide segments, use of repetitions, spell check

on input, automated search for terms in the database,

confirmation and saving of a segment, formal crite-

ria check with error message, spell check of all trans-

lation units, export of target text, editing of source

text, comments, automatic completion of the target

segment based on MT translation results, copying a

segment of source text into a segment of target text.

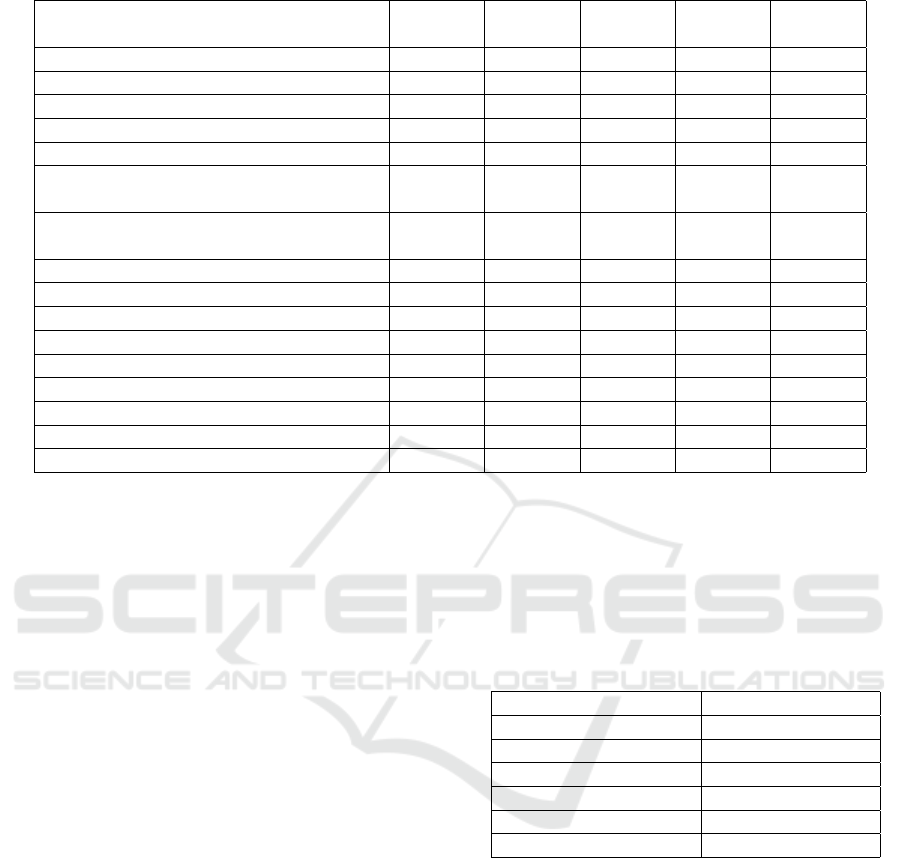

The results obtained (number of responses with a

score to each function) are presented in table 1.

The responses received indicate that the following

Memsource features received a 100% positive rating

(a positive rating was taken to mean a score of 4 and

5):

• display of full matches (26+41),

• display of fuzzy matches (30+37),

• integration with the MT system (8+59),

• use of repetitions (23+44),

• spellcheck on input (11+56),

• automated search for terms in the database

(26+41),

• confirmation and saving of a segment (18+49),

Developing Translators’ Soft Skills in a Cloud-Based Environment Using the Memsource System

625

Table 1: Comparison of selected mobile language learning applications (paid).

Function

Evaluation Evaluation Evaluation Evaluation Evaluation

1 2 3 4 5

Source text review during translation 0 0 4 18 45

Display of full matches 0 0 0 26 41

Display of fuzzy matches 0 0 0 30 37

Integration with the MT system 0 0 0 8 59

Editing of source text 3 6 7 48 3

Automatic completion of the target

0 0 12 38 17

segment based on MT translation results

Copying a segment of source text into

0 0 17 35 15

a segment of target text

Merge/divide segments 0 0 18 27 22

Use of repetitions 0 0 0 23 44

Spell check on input 0 0 0 11 56

Comments 5 7 35 9 11

Automated search for terms in the database 0 0 0 26 41

Confirmation and saving of a segment 0 0 0 18 49

Spell check of all translation units 0 0 0 13 54

Formal criteria check with error message 0 0 0 29 30

Export of target text 0 0 0 21 46

• spell check of all translation units (13+54),

• export of target text (21+46).

This high score for a significant number of func-

tions indicates that the students have understood their

benefits and usability, have mastered their skills and

realised their effectiveness.

At the same time, several functions received a

lower proportion of positive ratings, in particular:

• source text review during translation (94%),

• formal criteria check with error message (88%),

• automatic completion of the target segment based

on MT translation results (82%),

• copying a segment of source text into a segment

of target text (75%),

• merge/divide segments (73%).

This is, in our opinion, primarily because these

functions are not quite typical in the translation pro-

cess and the students have not fully understood their

meaning and necessity.

The two functions that received the most varied

evaluations were editing of the source text and com-

ments. It is likely that some students did not appreci-

ate their role in the translation process.

Overall, the vast majority of students who partic-

ipated in the experiential learning, positively evalu-

ating most features of the system, confirmed our as-

sumption about the use of Memsource as a core com-

ponent of a cloud-based environment.

At the same time, students were also generally

positive about the possibility to develop soft skills

when performing translation projects in a cloud-based

environment based on Memsource. Table 2 presents a

rating list of the skills highlighted by the students.

Table 2: List of soft skills developed in translation projects

using Memsource.

Skills/Abilities Number of responses

Digital skills 67

Ability to work in a team 64

Communicative skills 55

Ability to self-control 38

Responsibility 32

Leadership skills 5

As shown in table 2, all students improved their

digital skills. It should be noted that at the same

time during the verbal communication with the partic-

ipants of the experiment they stated their understand-

ing of the importance of these skills for their future

professional activities. Almost 100% indicated the

ability to work in a team, because without this abil-

ity of each team member, the project would not be

possible. About half of the students highlighted the

capacity for self-control and responsibility, which en-

courages us to increase our focus on developing these

personal qualities in the future. Quite a small num-

ber of participants in the experiment stated that they

had improved their leadership skills. This is explained

by the fact that the respective roles (administrator and

AET 2021 - Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

626

manager) were played by a small number of students,

as it actually happens in real professional activity.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The use of Memsource in the training of translators

contributes to the development of a number of soft

skills necessary for their future professional career,

namely:

• the ability to work in a team, fulfilling a specific

role assigned by the project administrator (man-

ager, linguist) and to practise relevant skills,

• leadership skills (in the case of the role of project

administrator or manager),

• the ability to communicate with others involved in

the project, which passes through the Memsource

system and requires the development of digital

skills,

• the ability to carry out self-monitoring of tasks

within a translation project consisting of time

management, meeting deadlines for a task or part

of a task, checking the quality of one’s own trans-

lation using the system functions, etc,

• the ability to make decisions at the level of their

role (e.g. to allocate tasks),

• responsibility for their part of a translation project

based on the awareness of the importance of their

own contribution to the common cause,

• digital skills as part of the technological training

of translators for professional activities in a new

environment using information technologies.

The use of the Memsource system as the main

component for creating a cloud-based environment

for training translators has shown that it can be used in

the educational process due to a number of significant

advantages, which include:

• accessibility through the offer of a demo and an

academic programme,

• easy for students to master, especially in cases

where they have already studied one of the desk-

top translation systems,

• the user-friendly interface, which greatly simpli-

fies working with the system,

• a wide functional range, allowing prospective

translators to practise the different roles of partic-

ipants in a translation project with relevant skills

and abilities,

• the prospect of applying the experience gained

with the system to future professional activities.

The cloud-based environment built using the

Memsource platform ensures that prospective trans-

lators are systematically equipped with the tools and

resources they need to carry out a full range of trans-

lation projects and, just as importantly, develop their

soft skills.

The creation of a cloud-based environment will

also optimise the structure and components of transla-

tion projects in the educational process of higher edu-

cation institutions that train translators. This involves

the justification, selection and enhancement of trans-

lation project tools, the basis of which will be cloud-

based automated translation systems integrated with

translation memory systems and systems for the cre-

ation and maintenance of educational and scientific

terminology databases.

REFERENCES

Bowker, L. (2002). Computer-Aided Translation Technol-

ogy: A Practical Introduction. Didactics of Trans-

lation. University of Ottawa Press, Ottawa. https:

//www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1ch78kf.

Bundgaard, K., Christensen, T. P., and Schjoldager, A.

(2016). Translator-computer interaction in action

— an observational process study of computer-aided

translation. The Journal of Specialised Transla-

tion, 25:106–130. https://www.jostrans.org/issue25/

art bundgaard.php.

Chan, S.-W. (2015). The development of translation tech-

nology: 1967–2013. In Chan, S.-W., editor, The Rout-

ledge Encyclopedia of Translation Technology, pages

3–31. Routledge, London, 1 edition. https://doi.org/

10.4324/9781315749129.

Choudhury, R. and McConnell, B. (2013). Trans-

lation technology landscape report. Technical

report, De Rijp. https://silo.tips/downloadFile/

translation-technology-landscape-report.

DePalma, D. A. and Sargent, B. B. (2013). Translation Ser-

vices and Software in the Cloud. How LSPs Will Move

to Cloud-Based Solutions. Common Sense Advisory,

Cambridge, MA. https://tinyurl.com/2zxfd5af.

Gamb

´

ın, J. (2014). Evolution of cloud-based translation

memory. MultiLingual, 25(3):46–49. https://dig.

multilingual.com/2014-04-05/index.html?page=46.

Imhof, T. (2014).

¨

Ubersetzung in der Cloud –

Geschichte, Tools und Trends. Infoblatt, (01):8–

10. http://web.archive.org/web/20150430005107/

http://infoblatt.adue-nord.de/infoblatt-2014-01.pdf.

Kautz, T. D., Heckman, J. J., Diris, R., ter Weel, B., and

Borghans, L. (2014). Fostering and Measuring Skills:

Improving Cognitive and Non-cognitive Skills to Pro-

mote Lifetime Success. Technical Report 110, OECD.

https://doi.org/10.1787/19939019.

Lippman, L. H., Ryberg, R., Carney, R., and

Moore, K. A. (2015). Workforce connec-

tions: Key “soft skills” that foster youth work-

Developing Translators’ Soft Skills in a Cloud-Based Environment Using the Memsource System

627

force success: Toward a consensus across

fields. Technical Report 2015-24, Child Trends.

https://web.archive.org/web/20161015025201/http:

//www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/

2015-24WFCSoftSkills1.pdf.

ManpowerGroup (2013). 2013 Talent Shortage Survey: re-

search results. http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/280848.

Muegge, U. (2013). Cloud-basierte

¨

Ubersetzungs-

Management-Systeme: Wer teilt, gewinnt. MD

¨

U:

Fachzeitschrift f

¨

ur Dolmetscher und

¨

Ubersetzer,

59(1):14–17.

O’Brien, S. (2012). Translation as human–computer in-

teraction. Translation Spaces, 1(1):101–122. https:

//doi.org/10.1075/ts.1.05obr.

Tarasenko, R. and Amelina, S. (2020). A unification of

the study of terminological resource management in

the automated translation systems as an innovative

element of technological training of translators. In

Sokolov, O., Zholtkevych, G., Yakovyna, V., Tara-

sich, Y., Kharchenko, V., Kobets, V., Burov, O., Se-

merikov, S., and Kravtsov, H., editors, Proceedings

of the 16th International Conference on ICT in Ed-

ucation, Research and Industrial Applications. Inte-

gration, Harmonization and Knowledge Transfer. Vol-

ume II: Workshops, Kharkiv, Ukraine, October 06-10,

2020, volume 2732 of CEUR Workshop Proceedings,

pages 1012–1027. CEUR-WS.org. https://ceur-ws.

org/Vol-2732/20201012.pdf.

Tarasenko, R. O., Amelina, S. M., and Azaryan, A. A.

(2020). Improving the content of training future trans-

lators in the aspect of studying modern CAT tools.

CTE Workshop Proceedings, 7:360–375. https://doi.

org/10.55056/cte.365.

Ultimate Languages (2018). What are CAT Tools?

https://ultimatelanguages.com/2018/10/16/

what-are-cat-tools/.

AET 2021 - Myroslav I. Zhaldak Symposium on Advances in Educational Technology

628