Using Merged Cancer Registry Data for Survival Analysis in Patients

Treated with Integrative Oncology: Conceptual Framework and First

Results of a Feasibility Study

Thomas Ostermann

1

, Sebastian Appelbaum

1,2

, Stephan Baumgartner

3

, Lukas Rist

4

and Daniel Krüerke

3,4

1

Methods and Statistics in Psychology, Faculty of Health, Witten/Herdecke University, Witten, Germany

2

Trimberg Research Academy, University of Bamberg, Bamberg, Germany

3

Society for Cancer Research, Hiscia Institute, Arlesheim, Switzerland

4

Clinic Arlesheim, Research Department, Arlesheim, Switzerland

daniel.krueerke@klinik-arlesheim.ch

Keywords: Survival Analysis, Clinical Registry, Cancer, Integrative Oncology.

Abstract: Survival analysis is the basis for research into all types of treatments aimed at prolonging the overall survival

of a cancer entity. Before we use data from a cancer registry at the Clinic Arlesheim (CRCA) for more

sophisticated survival analysis in relation to integrative oncology treatments, we wanted to learn more about

the possible differences between the clientele in this database and the public. In a first step we compared

survival rates for breast cancer and pancreatic cancer analyzed from CRCA-data with the cor-responding

survival rate (all stages) available at the Robert-Koch-Institute. Furthermore, we differentiated the survival

rates from CRCA-patients with respect to the fraction of the survival time in the care of the clinic Arlesheim.

While the survival rates of CRCA-patients with breast cancer or with pancreatic cancer show similar survival

rates compared to corresponding data from the Robert-Koch-Institute, the sensitivity analysis suggests that

the longer the fraction of the survival time in the care of the clinic Arlesheim the higher the expected survival

rates. In conclusion, the analysis and comparison of the survival rates of a clinical population of a cancer

registry, such as CRCA, may lead to a better identification of responders and non-responders and thus in the

long run may help to optimise integrative and patient cantered treatment strategies.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cancer in many cases still is a disease with fatal

outcome. According to GLOBOCAN database, 18.1

million new cancer cases and 9.6 million cancer

deaths worldwide were counted in 2018 with a 20%

risk of getting a cancer before age of 75 and a 10%

risk of dying from it (Ferlay et al., 2019). Thus, there

is an absolute necessity to be able to provide

statistical data on cancer incidence and treatments.

This is mainly done by cancer surveillance initiatives.

Cancer surveillance according to the National

Cancer Institute is the “ongoing, timely, and

systematic collection and analysis of information on

new cancer cases, extent of disease, screening tests,

treatment, survival, and cancer deaths (Stillman et al.,

2012).

Consequently, the reliability and functionality of

cancer surveillance relies on the ability to transfer

cancer data from hospitals, physicians and

laboratories into an environment where data can be

exchanged and made available (Pollack et al., 2020).

In a pragmatic view this is already the definition

of a cancer registry, which according to Bianconi et

al. (2012) is defined as “a systematic collection of a

clearly defined set of health and demographic data for

patients with specific health characteristics, held in a

central database for a predefined purpose”.

The history of cancer registries however started

very early before modern computer technology was

able to assist in fulfilling its purpose.

Ostermann, T., Appelbaum, S., Baumgartner, S., Rist, L. and Krüerke, D.

Using Merged Cancer Registry Data for Survival Analysis in Patients Treated with Integrative Oncology: Conceptual Framework and First Results of a Feasibility Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0010826400003123

In Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2022) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 463-468

ISBN: 978-989-758-552-4; ISSN: 2184-4305

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

463

1.1 History of Cancer Registries

With a deeper understanding of the pathogenesis of

cancer in the 19th century first ideas were developed

to gather reliable statistics in terms of cancer related

mortality or morbidity rates. In 1900, a first

nationwide survey on cancer was started by the

German Committee for Cancer Research (Wagner,

1991). According to (Meyer, 1911) “the committee's

first work should be directed towards the strength of

the enemy to be fought […]. Preparing for his

suppression means first of all to get a statistic of

cancer”. Therefore, questionnaires were sent to every

physician to record mortality rates due to cancer.

Another 30 years later according to Alam (2011),

a first population-based cancer registry was

established in Germany allowing to follow up the

treatment process including the duration of survival

of cancer patients, which was one of the starting

points of cancer epidemiology.

Today, the Federal Cancer Register Data Act from

2009, obligated the federal states to transmit data

from the federal states to the Center for Cancer

Registry Data at the Robert Koch-Institute, where

data is stored and used for epidemiological and

scientific purposes (Arndt et al., 2019) such as the

calculation of survival rates (SRs)

As already stated above, SRs provide information

about the percentage of people with the same cancer

and stage of cancer who survived a certain period

after diagnosis (usually five years) after a given

therapy. This information can be used to predict

therapy success on a probabilistic basis.

In particular, cancer registry data can be used to

identify patients with prolonged survival, which is

one of the main objectives in clinical oncology.

Keeping in mind that integrative treatment of cancer

may have a survival benefit for cancer patients (Bae

et al., 2019; Ostermann et al., 2020), registry data

from integrative inpatient treatment is a highly

valuable source not to be underestimated in health

services research.

1.2 The Cancer Registry of the Clinic

Arlesheim (CRCA)

The CRCA dates back to the late 1950

th

and the early

1960

th

(Leroi, A., 1959). The main idea of the

“medical records archive” as it was called at that time,

was to collect and process as many clinical

experiences as possible. In regular steps of one or two

years after inpatient treatment physicians were

contacted, to find out how the patients were doing.

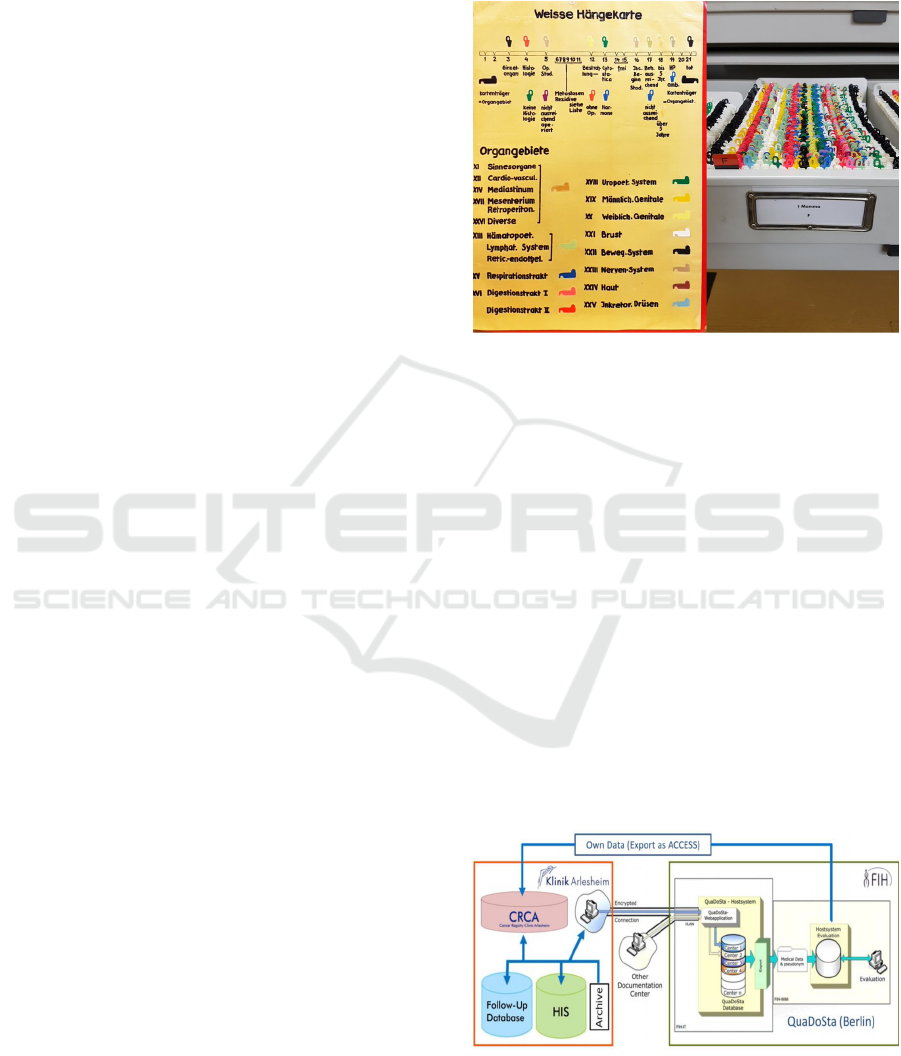

In house, the medical records collected in the

archive were available to the physicians for clinical

preparation as well as for research in a hanging card

register (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Structure of the former hanging card register of

the Clinic Arlesheim including organ areas

(“Organgebiete”) as well as informations on recurrent

cancer (“Rezidive) and type of therapy.

And indeed at that time first case reports on the

treatment of cancer were published (Leroi-von Mai,

1962; Leroi, A., & Wrede, E.;1967) but also a large

cohort study in 1.042 breast cancer patients was

published (Leroi, A. 1958).

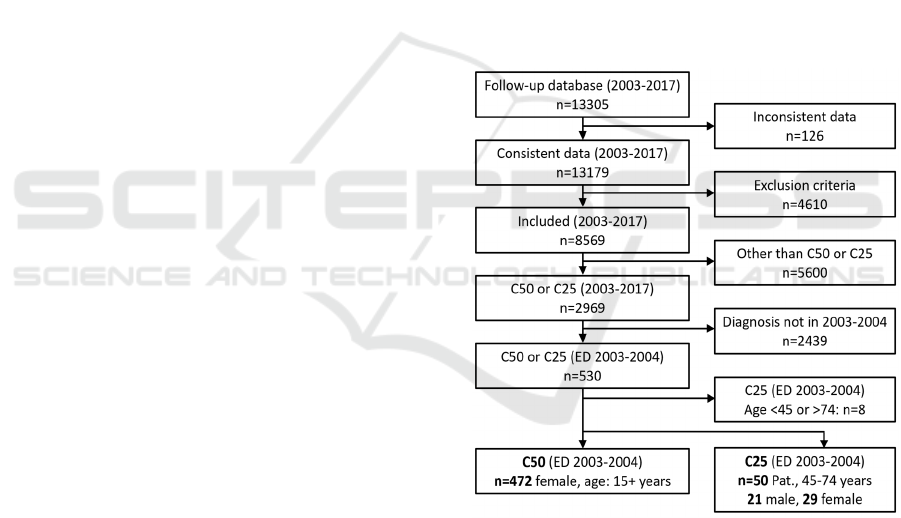

Today, the CRCA includes the documentation in

the international oncology database QuaDoSta

(Jeschke et al., 2007) located in Berlin Havelhöhe

(quality, documentation and statistics) since 2010, the

own hospital information system (HIS) since 2016

and a Follow-Up database since 1961. They

contribute with different size to the documentation of

the clinical course of various cancer entities in the

CRCA. Figure 2 describes how different sources of

documentation interact and contributing to finally

create the CRCA structure with all data sources.

Figure 2: Schematic representation of the CRCA structure

with all data sources contributing to the documentation.

HEALTHINF 2022 - 15th International Conference on Health Informatics

464

Before using data from the CRCA for more

sophisticated survival analysis regarding integrative

oncology treatments, the present study aims at

investigating the data about possible differences

between the clientele in the database and the public.

Thus, in a first step we compared SRs for patients

with breast cancer and pancreatic cancer respectively

analyzed from CRCA-data with the corresponding

SRs (all stages) available at the Center for Cancer

Registry Data at the Robert Koch-Institute.

Furthermore, we differentiated the SR from

CRCA-patients according to the fraction of the

survival time in the care of the clinic Arlesheim.

2 MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 Data Sources and Data

Management

We used the anonymized data for date of first

diagnosis, age at diagnosis, date of admission to the

Clinic Arlesheim and date of dead from the CRCA to

analyse survival times and rates for breast cancer and

pancreatic cancer patients.

Advanced data analysis is based on a conceptual

approach that contributes to a better understanding

which parameters and treatment modalities have a

positive impact on survival of major cancer entities.

The CRCA provides clinical information of more

than 14,000 cancer patients treated with integrative

medical concepts between 2003 and 2017 at either the

Lukas Clinic or the Ita Wegman Hospital and the

Clinic Arlesheim (the latter was founded in 2014 by

the fusion of the other two institutes). The CRCA

contains information on tumour location, date of

cancer diagnosis, TNM, consultations, diagnostics,

duration and frequency of conventional treatments as

well as integrative therapies, date and cause of death,

medical treatment regimens including doses and

application forms and many other detailed clinical

documentation on the course of cancer diseases.

Inclusion criteria for this extended documentation of

disease progression were:

- Diagnosis of malignancy at any of the following

sites:

• Pancreas (ICD10 C25),

• Colon and Rectum (C18 - C20),

• Lung (C34),

• Breast (C50),

• Prostate (C61).

- Valid informed consent

- At least 3 medical consultations within the first year

after registration in the CRCA (outpatients)

- At least 4 days of hospitalization within the first year

of registration in the CRCA (inpatients)

Exclusion Criteria:

- Medical consultation only within the first year of

registration in the CRCA.

- No malignant tumour

We selected freely available data from the Robert

Koch Institute (RKI) to compare our results with a

large national cancer registry (RKI 2017).

For a 10-year survival comparison, we had to take

data from the CRCA Follow-Up database with initial

diagnosis for C25 and C50 in 2003-2004. From this

database, we were able to use 472 breast cancer

patients (C50) and 50 pancreas cancer patients (C25)

for the following survival analysis, as shown in the

flowchart (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Patient flow chart for CRCA Follow-Up database

extraction of C50 and C25 patients, processed in the further

survival analysis.

2.2 Statistical Analysis

In a preliminary analysis, the data were prepared and

adjusted to be comparable to the survival data of the

RKI.

Survival time was defined as the time from the

date of first cancer diagnosis derived from the records

of the Clinic Arlesheim until the last follow-up date

or documentation of death.

Using Merged Cancer Registry Data for Survival Analysis in Patients Treated with Integrative Oncology: Conceptual Framework and First

Results of a Feasibility Study

465

The survival curves were estimated by the

Kaplan-Meier method (Schober & Vetter; 2018).

3 RESULTS

The C50 and C25 incidences and age distributions for

the CRCA Follow-Up database extraction and for the

RKI database query are summarized in Table 1.

The average age of the corresponding patients at

the clinic Arlesheim are about 5 to 10 years younger

than that of the patients registered in the RKI

database. This could be related to the fact, that

younger people are more open to integrative medicine

treatments than older generations.

Table 1: Sex-specific incidences and age distributions for

the patients from the CRCA Follow-Up database and for the

patients from the RKI database query (first diagnosed 2003-

2004, f=females, m=males).

SR of CRCA patients with breast cancer (age over

15y) or with pancreatic cancer (age 45-74y)

diagnosed 2003-2004, show similar survival curves

compared to corresponding data from the RKI

(compare Figure 4 and Figure 5a and 5b). The relative

3-year SR for breast cancer are 83% and 82% RKI,

for pancreatic cancer 20% and 21% RKI (women),

14%, and 15% RKI (men).

The sensitivity analysis suggests that the longer

the fraction of the survival time in the care of the

clinic Arlesheim (x/y STIC n), the higher the

expected SR (e.g. the 3-year SR for the >=1/2 STIC

group with 390 patients is about 7% higher than for

the overall group of 472 patients).

The obvious dependency of SR on the fraction of

the survival time in the care of the clinic Arlesheim

can have many origins as we possess only limited

knowledge of detailed treatments outside the clinic.

Patients who used the integrative care at the clinic

Arlesheim only during a short period of their survival

time, may have undergone inadequate treatment

Figure 4: Kaplan-Meier estimates of SR for breast cancer

patients of the Clinic Arlesheim (C50) compared to data

from the Robert Koch Institute (RKI), diagnosed between

2003 to 2004 (age over 15y). [x/y STIC n = fraction of

Survival Time In Care of Clinic Arlesheim and number of

patients in this group (f=females, m=males)].

elsewhere or despite extensive conventional

treatments they showed poor prognosis and used

integrative treatments only in progressed states. It’s

noteworthy that the x/y STICn-factor seems to be

capable to distinguish between different groups with

different survival time. Therefore, statistical concepts

such as random forest analysis are currently being

adapted to these results in order to gain a deeper

understanding of the parameters and treatment

modalities that influence SR.

Figure 5a: Kaplan Meier estimates of SR for female

pancreatic cancer patients of the Clinic Arlesheim (C25)

compared to data from the Robert Koch Institute (RKI),

diagnosed between 2003 to 2004 (age 45-74y). [x/y STIC

n: see caption Fig. 2].

Registry ICD10 Sex N Age ± SD / y

C50 f 472 53.9 ± 12.5

CRCA

C25 f 29 61.8 ± 9.7

C25 m 21 62.4 ± 7.5

C50 f 122922 63.2 ± 13.8

RKI

C25 f 14119 72.4 ± 11.0

C25 m 13572 67.8 ± 10.7

HEALTHINF 2022 - 15th International Conference on Health Informatics

466

Figure 5b: Kaplan Meier estimates of SR for male

pancreatic cancer patients of the Clinic Arlesheim (C25)

compared to data from the Robert Koch Institute (RKI),

diagnosed between 2003 to 2004 (age 45-74y). [x/y STIC

n: see caption Fig. 3].

4 CONCLUSIONS

The analysis and comparison of the SR of a clinical

population of a cancer registry, such as CRCA, may

lead to a better identification of responders and non-

responders to integrative treatments (Winkler et al.,

2018). For this purpose, a high data quality of the

patient's treatment documentation is indispensable for

comprehensive statistics from the cancer registry to

contribute to cancer prevention in integrative

oncology.

From a methodological point of view, complex

statistical approaches such as the concept of frailty to

introduce random effects, association and unobserved

heterogeneity into models for survival data according

to (Martins et al.; 2019) is a current challenge which

extends the Cox model of proportional hazards model

by introducing individual factors such as therapeutic

gap times to survival analysis and will be applied to

this data (Hirsch et al., 2016; Yazdani et al., 2019).

Figure 5 illustrates typical sequences of therapy

and non-therapy sections in the courses of a disease,

which can be analysed concerning e.g. SR with

respect to “gap time” or “total time” for instance.

As a consequence this might not only lead to an

identification of responders in cancer patients but also

to a detection of optimal treatment strategies for

patient subgroups undergoing an integrative

oncologic treatment (Haller et al., 2021).

Figure 6: Frailty model to model therapeutic “gap times”.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank Prof. Dr. med.

Andreas Wienke (University Halle/Saale) for the

provision of the illustration in Figure 5. We also

would like to explicitly appreciate the friendly

support and constant helpfulness with all questions

concerning the QDS system by the FIH team (Antje

Merkle, Danilo Pranga and Friedemann Schad).

REFERENCES

Alam, A.S. (2011): Cancer Registry and Its Different

Aspects. Journal of Enam Medical College; 1(2): 76-80.

Arndt, V., Holleczek, B., Kajüter, H., Luttmann, S.,

Nennecke, A., Zeissig, S. R., Kraywinkel, K. &

Katalinic, A. (2020). Data from population-based

cancer registration for secondary data analysis:

methodological challenges and perspectives. Das

Gesundheitswesen, 82(S 01), S62-S71.

Bae K, Kim E, Kong JS, et al. (2019): Integrative cancer

treatment may have a survival benefit in patients with

lung cancer: A retrospective cohort study from an

integrative cancer center in Korea. Medicine; 98(26):

e16048.

Bianconi, F., Brunori, V., Valigi, P., La Rosa, F., & Stracci,

F. (2012). Information technology as tools for cancer

registry and regional cancer network integration. IEEE

Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics-Part

A: Systems and Humans, 42(6), 1410-1424.

Ferlay, J., Colombet, M., Soerjomataram, I., Mathers, C.,

Parkin, D. M., Piñeros, M., Znaor, A. & Bray, F. (2019).

Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in

2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. International

journal of cancer, 144(8), 1941-1953.

Haller, H., Voiß, P., Cramer, H., Paul, A., Reinisch, M.,

Appelbaum, S., Dobos, G., Sauer, G., Kümmel, S. &

Thomas Ostermann & Ostermann, T. (2021). The

INTREST registry: protocol of a multicenter

Using Merged Cancer Registry Data for Survival Analysis in Patients Treated with Integrative Oncology: Conceptual Framework and First

Results of a Feasibility Study

467

prospective cohort study of predictors of women’s

response to integrative breast cancer treatment. BMC

Cancer, 21(1), 1-9.

Hirsch K, Wienke A, Kuss O (2016): Log-normal frailty

models fitted as Poisson generalized linear mixed

models. Computer methods and programs in

biomedicine; 137: 167-175.

Jeschke, E., Schad, F., Pissarek, J., Matthes, B., Albrecht,

U., & Matthes, H. (2007). QuaDoSta—a freely

configurable system which facilitates multi-centric data

collection for healthcare and medical research. MS

Medizinische Informatik, Biometrie und

Epidemiologie, 2007-3.

Leroi, A. (1958). Post-operative Iscador therapy for breast

carcinoma. British Homeopathic Journal, 47(03), 191-

200.

Leroi, A. (1959). Jahresbericht des Vereins für

Krebsforschung" Arlesheim.

Leroi, A. & Wrede, E. (1967). Progress in iscador therapy

of malignant tumours. British Homeopathic Journal,

56(01), 2-19.

Leroi-von May, R. (1962). Progress in Iscador therapy of

malignant tumours. British Homeopathic Journal,

51(03), 176-185.

Martins, A., Aerts, M., Hens, N., Wienke, A., & Abrams, S.

(2019). Correlated gamma frailty models for bivariate

survival time data. Statistical methods in medical

research, 28(10-11), 3437-3450.

Meyer G (1911): Bericht über die zehnjährige Wirksamkeit

des Deutschen Zentralkomitees für Krebsforschung.

Zeitschrift für Krebsforschung; 10: 8–33.

Ostermann T, Appelbaum S, Poier D et al. (2020): A

Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Survival

of Cancer Patients Treated with a Fermented Viscum

album L. Extract (Iscador): An Update of Findings.

Complementary Medicine Research 27(4), 1-12.

Pollack, L. A., Jones, S. F., Blumenthal, W., Alimi, T. O.,

Jones, D. E., Rogers, J. D., Benard, V.B. & Richardson,

L. C. (2020). Population Health Informatics Can

Advance Interoperability: National Program of Cancer

Registries Electronic Pathology Reporting Project. JCO

Clinical Cancer Informatics, 4, 985-992.

RKI, Krebsregisterdaten im Robert Koch-Institut,

https://www.krebsdaten.de/Krebs/EN/Database

(database query 27.11.2017)

Schober, P., & Vetter, T. R. (2018). Survival analysis and

interpretation of time-to-event data: the tortoise and the

hare. Anesthesia and analgesia, 127(3), 792-98.

Stillman, F. A., Kaufman, M. R., Kibria, N., Eser, S.,

Spires, M., & Pustu, Y. (2012). Cancer registries in four

provinces in Turkey: a case study. Globalization and

health, 8(1), 1-8.

Wagner G (1991): History of cancer registration. In: Jensen

OM, Parkin DM, MacLennan R et al, (eds). Cancer

registration: principles and methods. IARC scientific

publication 95. Lyon: International Agency for

Research on Cancer, 3-6.

Winkler M, Reissmann R, Sauer G et al. (2018): Einfluss

eines integrativonkologischen Therapieprogramms auf

die Therapieresponse von Brustkrebspatientinnen: eine

prospektive Kohortenstudie (INTEREST). Senologie-

Zeitschrift für Mammadiagnostik und –therapie;

15(02), 152.

Yazdani A, Yaseri M, Haghighat S et al. (2019):

Investigation of Prognostic Factors of Survival in

Breast Cancer Using a Frailty Model: A Multicenter

Study. Breast cancer: basic and clinical research; 13:

1178223419879112.

HEALTHINF 2022 - 15th International Conference on Health Informatics

468