The Mindfulness Meditation Effect on States of Anxiety,

Depression, Stress and Quality of Life

Pedro Morais

1a

, Ana P. Pinheiro

2b

, Miguel S. Fonseca

3c

and Carla Quintão

4d

1

LIBPhys, NOVA School of Science and Technology, NOVA University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal

2

Faculty of Psychology, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal

3

Center for Mathematics and Applications, NOVA School of Science and Technology,

NOVA University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal

4

NOVA School of Science and Technology - Department of Physics, NOVA University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal

Keywords: Mindfulness, Anxiety, Depression, Stress, Quality-of-Life.

Abstract: Purpose: This paper aims to study how mindfulness meditation can be used to prevent, or improve, states of

anxiety, depression, stress and loss of quality of life. Although this model of meditation has been associated

with a healthier life, there is a need for scientific evidence-based on longitudinal results. Methods: Twenty-

five volunteers, asymptomatic of psychological distress, participated in this research project attending a

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) course. The status of each individual was assessed for 18

weeks, with three scales: World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL), Profile of Mood States

(POMS) and Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS). There were four evaluation periods:

Pre/Peri/Post-MBSR course and a fourth follow-up, after two months. Results: Comparing the beginning to

the end of the MBSR course, a significant reduction was observed in mean results of self-reported anxiety: -

66.0% (p<0.001), stress: -52.0% (p<0.001), depression: -51.0% (p<0.001) and Total Mood Disturbance

(TMD): -19.0% (p<0.001), as well as an increase in quality of life: 11.2% (p<0.001). Conclusion: The current

values suggest that the practice of mindfulness meditation, characterized by self-regulation of attention, can

be used as a proactive way to prevent and respond to psychopathological disorders.

1 INTRODUCTION

Being healthy is much more than not being sick

(World Health Organization, 2014), involving daily

physical and mental well-being. The modern society,

of which we are part of, imposes increasing personal

responsibilities, an increasingly demanding

professional activity and a constant connection to the

technological world. New obligations arise daily,

preventing a timely response to problems. There is no

room to rest and the mind tends to walk into a state of

stress. This vulnerable and unhealthy way of life is

evidenced by a study published by the OCDE in

which more than 80 million Europeans suffer from

mental health problems (OECD, 2018). The search

for a healthy and effective alternative, without using

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1774-7093

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7981-3682

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0162-8372

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1015-4655

drugs, becomes a real demand. Mindfulness

meditation comes as part of the solution to this type

of disorder. It consists of a mental self-regulation

technique of controlling attention and, consequently,

the individual’s well-being. Mindfulness, which

underlies the principle of observing without

judgment, calms the mind, acting not only from the

therapeutic point of view but mainly by preventing or

aiding a treatment of mental disorders that affect a

large part of the population. This type of meditation

has evolved worldwide with very significant results

in the quality of life of its followers. There is a

growing number of practitioners and countries such

as England (Education et al., n.d.), Portugal (João

Carvalho das Neves, João Pargana, 2019), Australia

(Dobkin & Hutchinson, 2013) and the USA where

Mindfulness has already become a curricular

Morais, P., Pinheiro, A., Fonseca, M. and Quintão, C.

The Mindfulness Meditation Effect on States of Anxiety, Depression, Stress and Quality of Life.

DOI: 10.5220/0010854900003123

In Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2022) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 573-582

ISBN: 978-989-758-552-4; ISSN: 2184-4305

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

573

discipline (Weare, 2018) and also used as medical

care (Vos & Vitali, 2018)(Kemper et al.,

2016)(Mouzinho et al., 2018).

Several meta-analyses demonstrated positive

effects of mindfulness meditation on stress, anxiety

and depression (Spijkerman et al., 2016)(Li et al.,

2017). Furthermore, by comparing Mindfulness to

other types of meditation, such as Yoga, the first was

shown to produce clearly superior effects (Virgili,

2015). Studies at various universities advise

Mindfulness meditation as an effective method for

calming stress levels among the student population

(Galante et al., 2018). Nevertheless, the benefits of

this practice need to be ascertained (Galante et al.,

2016). Clinical situations such as chronic pain or low

back pain (Hilton et al., 2017) might be relieved with

the aid of Mindfulness (Anheyer et al., 2017).

However, the temporal sequence in evaluations is

required. Some approaches already address this need,

such as the Mindfulness study of 104 international

students at the University of Amsterdam being

collected during four meditation course sessions (de

Bruin et al., 2015).

Notwithstanding, a longitudinal study addressing

different aspects of well-being and mental health is

missing. There are several articles published based on

WHOQOL survey. In a study conducted at a

university hospital in Seoul, the effects of

Mindfulness meditation on 50 nurses were evaluated.

With an 8-week course, they found significant

improvements in nurses’ quality of life and increased

positive emotional states (Chang et al., 2016). A

meta-analysis of 96 studies with 7647 participants

also found positive outcomes of the MBSR course on

volunteer’s quality of life (de Vibe et al., 2017) and

relief of depressive symptoms (Manh Dang et al.,

2018). Identical results, with clear improvements in

the health status of each individual, were also

revealed using POMS (Evans et al., 2018)(Garland et

al., 2007) and DASS (McConville et al.,

2017)(Kolahkaj & Zargar, 2015) surveys. The studies

compared the states pre and post-course and revealed

reductions in depression, which are more significant

on anxiety and even more on stress.

Most papers published in this area only perform

comparative studies between test and control groups

in a single moment, disregarding the dynamics of the

emotional states and the intrinsic nature of training,

which demands continued practice (Tang et al.,

2015). It is expected that after the participation in the

MBSR course, psychological changes occur in the

individual, providing a more positive life approach

without known negative collateral damage. However,

it is important to assess until when the effects persist.

The main objectives of this study were to specify

the contribution of the current practice of

Mindfulness meditation to the prevention and

management of mood dysregulation such as anxiety,

depression and/or stress. Three different surveys

(DASS, POMS and WHOQOL-100) were used to

evaluate the well-being subjects evolution.

Longitudinal monitoring was carried out over 18

weeks, through 4 collection sessions, and the

existence of only one test group was characterized in

the first session and kept as the baseline for the

subsequent sessions.

2 METHODS

The present study is based on the administration of a

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) course

to 30 individuals and its evaluation was performed

over 18 weeks. Through a longitudinal approach, with

records from 4 sessions, three scales assessed the

current Quality of Life (QoL) of the participants, their

mood state and the levels of depression, anxiety and

stress.

2.1 Participants Recruitment and

Sample Characterization

The participant’s selection was made in a Portuguese

University where this research work took place.

Recruitment began with the dissemination of posters

through Facebook and sent via e-mail to all faculty

members, students and employees. Through a QR

code/link, those who were interested, were provided

access to a Web page with more detailed information

such as the instructor’s name, the sessions scheduled

and the attribution of a certificate to all those who

successfully completed it. For 15 days, an online

mini-survey was active, allowing to pre-select the

candidates. All those who did not belong to this

academic environment already had training in

Mindfulness or were not available to attend the entire

course were excluded. The page registered 279

accesses with 35 applications, resulting in the

rejection of 5 individuals (1 did not belong to the

university, 3 already had Mindfulness training and 1

did not have full availability to attend the course).

Subsequently, during the MBSR course, 5 individuals

gave up (2 for health issues and 3 without

justification), so the final population considered for

this study was composed of 25 individuals (mean age

= 26.0, SD = 7.1, 9 male) (Table 1).

HEALTHINF 2022 - 15th International Conference on Health Informatics

574

Table 1: Sample characterization.

Age

Total

Male

Female

Master

student

PhD

student

Employee

<20 3 1 2 3 0 0

20-25 10 5 5 10 0 0

25-30 8 2 6 4 2 2

≥30 4 1 3 1 3 0

2.2 Mindfulness-based Stress

Reduction Course

The MBSR training is specifically targeted to

situations of stress, anxiety and depression(Grossman

et al., 2004). It was developed to be trained in 8

lessons of 2 hours and 30 minutes each, one per week.

In the 6

th

week, an intensive training session was

prepared, usually on a Sunday, in a silent regime of

"retreat", putting into practice the knowledge already

acquired (Table 2).

Table 2: Plan for MBSR Training Course.

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction

topics

Hours

Week

of the

year

Introduction to Mindfulness 2.5 21

th

Perception 2.5 22

th

Mindfulness of breath & body in motion 2.5 23

th

Learning about our patterns of stress

reaction

2.5 24

th

Dealing with stress: Using Mindfulness to

respond instead of to react

2.5 25

th

Stressful communications and

interpersonal Mindfulness

2.5 26

th

(Silent retreat) 6.0 26

th

Lifestyle choices: Take care of me 2.5 27

th

Keep Mindfulness alive 1.5 28

th

2.3 Online Surveys

The DASS, POMS and WHOQOL-100 inquiries

were implemented through the Google Forms

platform, collecting and pre-processing data. After

the application submission, the selected volunteers

received an SMS with a random alphanumeric 6

digits, corresponding to their personal and non-

transferable identification. Personal data privacy is

guaranteed using HTTPS protocol and this code

authentication without any other identification.

In the four sessions scheduled, the DASS and

POMS surveys were completed, with a 15-minute

completion time. To avoid a time overload in the

collection session, the WHOQOL-100 survey,

estimated at 25 minutes, were answered online later,

on the day itself. The surveys were answered at

different stages of the academic calendar (Table 3).

Table 3: School Calendar during the 4 sessions surveys.

Session Date (last 2 weeks) Academic calendar

1

st

May School days

2

nd

June Exams

3

rd

July Special period of exams/

Paper submissions

- August Summer holidays (full

month)

4

th

September School days

2.3.1 Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale

The DASS, adapted to Portuguese with 21 questions

(Pais-Ribeiro et al., 2004) and answered from 0 to 3,

was developed for adults in order to evaluate a set of

emotions and feelings, lived in the last week, and

grouped in three basic structures: Anxiety, depression

and stress. The issues related to anxiety include

subjective experiences, skeletal muscle effects,

autonomic system arousal and situational anxiety.

Depression encompasses discouragement, lack of

interest or involvement, inertia, self-depreciation and

devaluation of life. Finally, stress encompasses

irritability, nervous excitement, impatience,

restlessness, and difficulty in relaxing. The healthiest

individual will get a final score of 0 progressing to a

maximum of 42, evolving from "Normal" to

"Medium," "Moderate," "Severe," and "Extremely

Severe". Although each state has a maximum value of

42, its classification varies according to each state

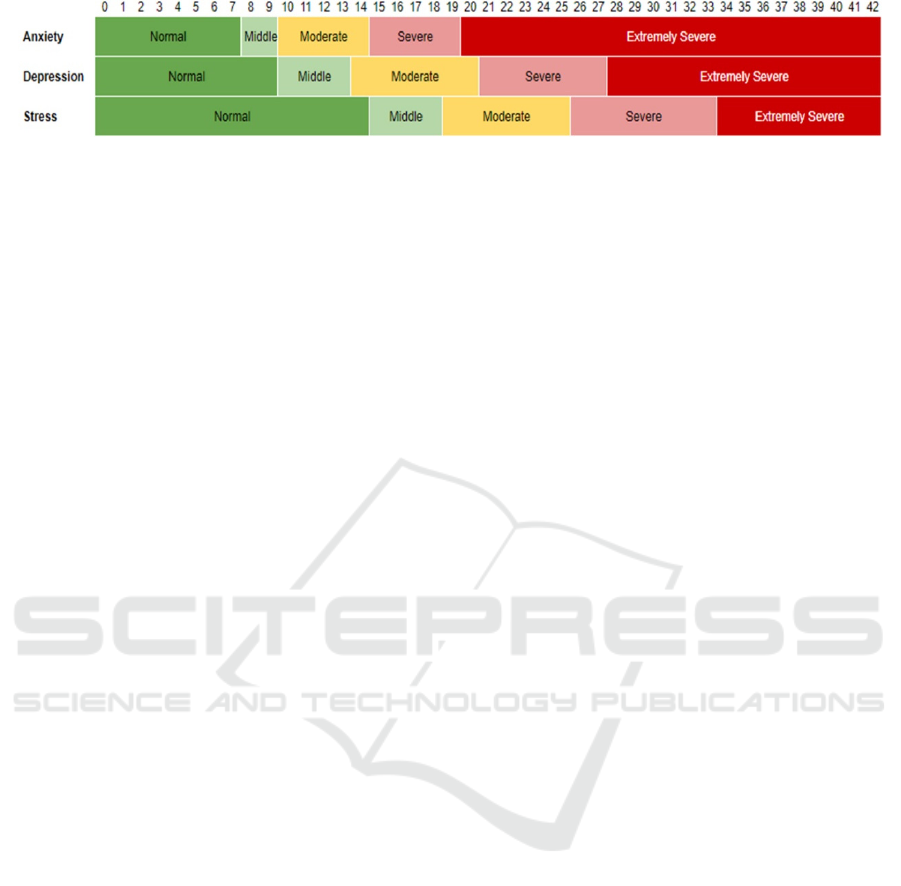

analysis (Figure 1).

2.3.2 Profile of Mood States

POMS is an easy-to-respond and easy-to-use

assessment instrument that evaluates mood states and

psychological well-being (McNair et al., 1971). In the

Portuguese adaptation (Faro Viana et al., 2012) 42

adjectives were used, identifying six state factors:

Stress/Anxiety is represented by an increase of

tension; Depression/Melancholy describes the

emotional state of sadness, loneliness, unhappiness

and discouragement; Hostility/Anger depicts a mood

of anger or dislike of others; Vigor/Activity

represents

the state of energy and physical and

The Mindfulness Meditation Effect on States of Anxiety, Depression, Stress and Quality of Life

575

Figure 1: Qualitative/Quantitative Classification for Anxiety, Depression and Stress, using DASS scale.

psychological vigor; Fatigue/Inertia expresses a state

of fatigue, inertia and reduced energy; and finally

Confusion/Disorientation corresponds to a low

lucidity and confused state. All questions were

presented online, and evaluate the person status

during the last week, on a scale of 0 to 4

(0="Nothing", 1="A little", 2="Moderately", 3="Fair"

and 4="Many"). The final mood state is calculated

through the sum of the states of tension, depression,

hostility, fatigue and confusion, from which the state

of vigor is subtracted. To avoid a negative final result,

the value 100 is added to the sum. This TMD is

represented by the final value obtained. A lower value

represents a more positive mood state.

2.3.3 Quality of Life

The WHOQOL survey is intended to assess the

quality of life of an individual, taking into account his

"perception and position in life in a cultural context

and system of values in which he lives and in relation

to his goals, expectations, standards and concerns"

(World Health Organization, 1998). The WHOQOL-

100 consists of 100 questions adapted to the

Portuguese population assessing the physical,

psychological, independence, social relations,

personal environment and spirituality/beliefs.

Responses are given based on the individual

experience during the past two weeks. The first 42

questions are related to positive feelings of happiness

and contentment. The rating ranges from "Nothing"

to "Too Much". The daily activities are assessed with

13 questions with a score of "Nothing" to

"Completely", checking whether the subject

experienced or was able to do certain things such as

washing themselves or eating. The third phase

includes 34 questions to evaluate if the individual felt

satisfied, happy or well with various aspects of their

life, ranging from "Very dissatisfied" to "Very

satisfied". The 5

th

analysis phase includes 4 questions

about the daily activities that take the most time and

energy, varying the classification between

"Nothing/Very dissatisfied" to "Completely/Very

satisfied". Next, there are four more questions

assessing an individual's physical ability to

accomplish what they need to do by ranking "Very

Bad/Not at All/Very Dissatisfied" and "Very

Good/Very Satisfied". Finally, the last four questions

address personal beliefs and spirituality, with the

responses varying between "Nothing" and "Many".

Quality of life is then assessed quantitatively in all

these six domains, from 1 to 5. The higher the result

obtained, the more quality of life an individual has.

This survey was completed only in the first, third and

fourth sessions, with no data collection occurring on

the second (Peri-MBSR). This decision occurred

since filling this questionnaire is very time-

consuming, and the major goal of the survey is to

evaluate the changes before, after the course, and

after two months.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using a linear

mixed-effects model. This approach is particularly

appropriate to process longitudinal data with missing

values. This model considers the independent effects

of interest (fixed effects) and the variations that may

occur (random effects). The model included one

random effect (subjects) and one fixed effect

(sessions). The analysis was performed using

FITLME command of Matlab (MathWorks, 2020).

The completed command was: lme = fitlme (tbl,

formula), where tbl is the data table, previously

structured in an adequate format, and

formula=’data~1+session+(1|patient)

’.

3 RESULTS

The data related to DASS and POMS surveys in the

four sessions (21 and 42 questions respectively), and

the WHOQOL-100 survey (100 questions in 3

sessions), in a total of 13.800 responses, were

processed. The datasets were labeled with "Pre",

"Peri", "Post" and "Follow-Up", corresponding to

"Pre-Course", "During Course", “Post-Course" and

"2 Months after Course".

HEALTHINF 2022 - 15th International Conference on Health Informatics

576

Figure 2: DASS survey averaged results for Anxiety, Depression and Stress (from 0 to 42), from session 1 (S1) to session 4

(S4), for the global sample. The error bars represent the standard deviation.

Table 4: DASS survey results (mean; standard deviation, SD, and p-value) for anxiety, depression and stress (from 0 to 42),

for the entire sample.

DASS Survey

Pre-MBSR (S1) Peri-MBSR (S2) Post-MBSR (S3) Follow-up MBSR (S4)

Mean SD Mean SD p(S1-S2) Mean SD p(S1-S3) Mean SD p(S1-S4)

Anxiety 10.3 ± 1.5 6.8 ± 0.9 < 0.01 3.5 ± 0.7 < 0.001 6.2 ± 1.5 < 0.01

Depression 10.4 ± 1.7 7.6 ± 1.2 0.07 5.1 ± 1.0 < 0.001 7.4 ± 1.6 < 0.05

Stress 19.6 ± 1.3 15.8 ± 1.2 < 0.05 9.4 ± 1.3 < 0.001 12.9 ± 2.1 < 0.001

3.1 DASS Survey

When considering the global sample, the DASS

survey revealed a general improvement in all

assessment parameters. The average state of

depression dropped from the first session to the

following from a qualitative grade of "Medium" to

"Normal". Anxiety also exhibited the same pattern

being reduced from "Moderate" to "Normal". Self-

reported stress also decreased between the first and

second sessions from "Moderate" to "Medium" and

then to "Normal" in the remaining two sessions.

These findings indicate that the Mindfulness course

does influence the parameters measured in the DASS

survey (Figure 2). In Table 4 we present separate

results for anxiety, depression, and stress, as well as

the p-values obtained when data from session 1 was

compared with data from the other 3 sessions. It is

worth noting that only one contrast did not reach

statistically significant, i.e., p≥0.05 (Depression:

session 1 against session 2). Since DASS included

both qualitative and quantitative discrimination

(Figure 1), it allowed the creation of two subgroups

of participants, one with low ("Normal" or

"Medium") and the other with high levels

("Moderate", "Severe" or "Extremely severe"). The

overall results obtained indicate the existence of 14

subjects with “Moderate” to “Extremely Severe”

levels of anxiety, 7 with depression and 14 with stress

(Table 5). Comparing the first (Pre-MBSR) with the

third session (Post-MBSR), 12 out of 14 (85.7%)

subjects lowered their anxiety state to "Normal" or

Table 5: Evaluation of Anxiety, Depression and Stress

using DASS data in subjects who presented high levels of

these conditions in the first session.

State

Condition

Pre-MBSR

(S1)

Peri-MBSR

(S2)

Post-MBSR

(S3)

Follow-up

MBSR (S4)

Anxiety ≥10 14 9 2 4

Depression ≥ 14 7 5 2 4

Stress ≥ 19 14 6 1 6

"Medium". The same pattern was observed for

depression in 5 out of 7 (71.4%) subjects and for

stress in 13 out of 14 subjects (92.9%). This indicates

that post-training changes were enhanced in

participants who presented more extreme anxiety and

stress scores in the baseline assessment. Considering

the results in a globally, at the end of MBSR course,

92% of participants (25) reported "Normal" or

"Medium" levels of anxiety, 92% of depression and

96% of stress.

3.2 POMS Survey

The POMS states are evaluated with a score ranging

from 0 to 4. The tension, hostility, vigor, fatigue and

depression are calculated considering the sum of 6

questions each, being 0 to 24 the possible range

obtained for each state. The depression score is

obtained based on 12 questions varying from 0 to 48.

The Mindfulness Meditation Effect on States of Anxiety, Depression, Stress and Quality of Life

577

Figure 3: POMS survey averaged results for Tension, Hostility, Fatigue, Confusion, Vigor (from 0 to 24), Depression (from

0 to 48) and TMD (from 76 to 244). The error bars represent the standard deviation.

Table 6: POMS survey results (mean; standard deviation, SD, and p-value) for Tension, Depression, Hostility, Fatigue,

Confusion, Vigor and Total Mood Disturbance for the global sample.

POMS Survey

Pre-MBSR (S1) Peri-MBSR (S2) Post-MBSR (S3) Follow-up MBSR (S4)

Mean SD Mean SD p(S1-S2) Mean SD p(S1-S3) Mean SD p(S1-S4)

Tension 12.2 ± 0.7 9.0 ± 0.7 <0.001 6.5 ± 0.8 < 0.001 8.1 ± 1.2 < 0.001

Depression 13.4 ± 2.0 9.4 ± 1.3 < 0.01 6.8 ± 1.4 < 0.001 8.4 ± 1.9 < 0.001

Hostility 7.5 ± 0.7 6.3 ± 0.8 0.18 4.2 ± 0.7 < 0.001 3.9 ± 0.8 < 0.001

Fatigue 12.2 ± 1.1 8.9 ± 1.1 < 0.01 6.0 ± 1.1 < 0.001 9.1 ± 1.6 < 0.01

Confusion 9.2 ± 1.0 7.3 ± 0.7 < 0.01 6.3 ± 0.7 < 0.001 6.2 ± 0.9 < 0.001

Vigor 13.9 ± 0.8 14.1 ± 0.8 0.78 16.0 ± 0.8 < 0.05 15.3 ± 1.0 0.06

TMD 140.6 ± 5.0 126.8 ± 4.1 < 0.01 113.9 ± 4.4 < 0.001 120.3 ± 5.9 < 0.001

Considering the global sample, the results

comparison from Pre-MBSR to Post-MBSR sessions

revealed an increase in the vigor level (15.1%) and an

expressive reduction in the remaining states: Tension

-46.7%, Depression -49.3%, Hostility -44.0%,

Fatigue -50.8% and Confusion -31.5% (Figure 3).

This changing pattern was also verified in the

intermediate stage of the MBRS course from the first

to the second session. The comparison of the third

session with the fourth session revealed a general

reduction trend in negative mood states (Table 6 and

Figure 3). Finally, the comparison of the TMD index

from the Pre-MBSR to Post-MBSR session showed a

reduction of -19.0%. We also performed a global

statistical analysis similar to the one described for the

DASS survey. When comparing each session with the

first one (Table 6) only three contrasts did not reach

statistical significance, i.e. hostility from the first to

the second session and vigor from the first to the

second and fourth session.

3.3 WHOQOL-100 Survey

The WHOQOL-100 survey comprises 100 questions

ranging from 1 to 5. Each evaluation is performed

through 4 answers, with five levels each, resulting in

a minimum value of 4 and a maximum value of 20.

Compared to previous surveys, the scale

interpretation must be reversed, that is, the quality of

life is considered higher as the value increases.

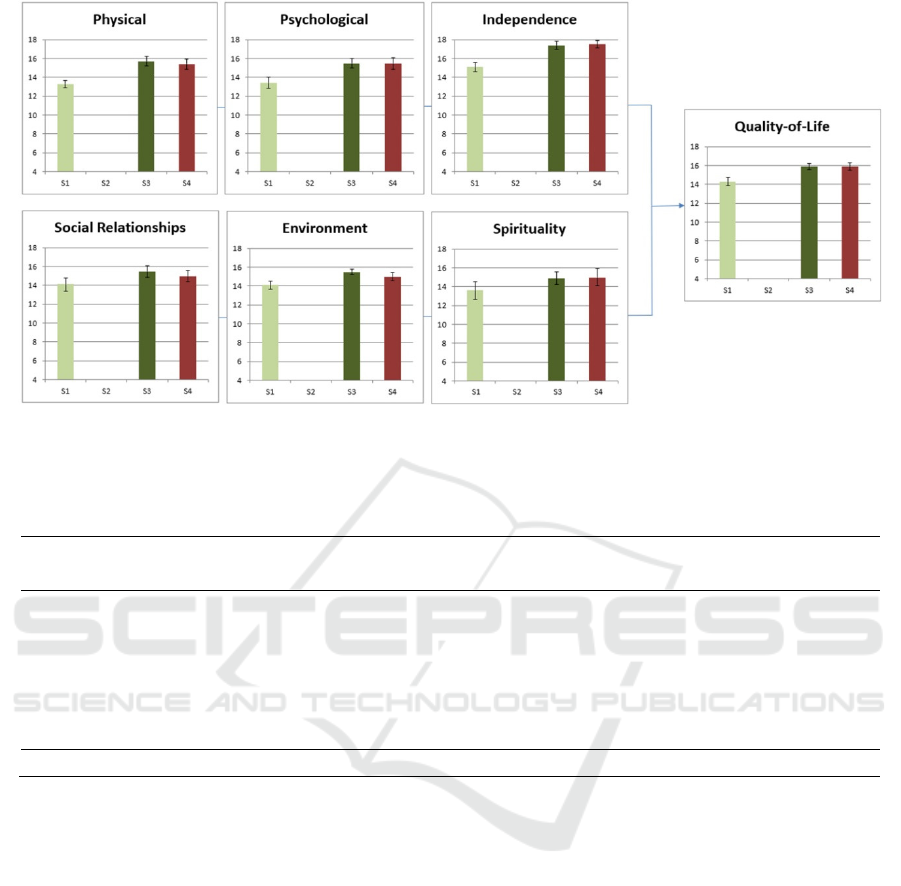

Regarding the analysis of individual states (Table 7

and Figure 4) an improvement from the Pre-MBSR to

the Post-MBSR was observed at all levels: Physical

(15.8%), Psychological (15.7%); Independence

(15.2%), Social Relationships (9.9%), Environment

(9.4%), and Spirituality (9.6%). The final state

Quality-of-Life that integrates all previous ones

HEALTHINF 2022 - 15th International Conference on Health Informatics

578

Figure 4: WHOQOL-100 survey averaged results for physical, psychological, independence, social relationships,

environment, spirituality and quality-of-life items (from 4 to 20). The error bars represent the standard deviation.

Table 7: WHOQOL survey results (mean; standard deviation, SD, and p-value) for physical, psychology, independence, social

relationships, environment and spirituality items, in the global sample.

WHOQOL-100 Survey

Pre-MBSR (S1) Post-MBSR (S3) Follow-up MBSR (S4)

Mean SD Mean SD p(S1-S3) Mean SD p(S1-S4)

Physical 13.3 ± 0.4 15.7 ± 0.5 < 0.001 15.4 ± 0.5 < 0.001

Psychological 13.4 ± 0.6 15.5 ± 0.5 < 0.001 15.5 ± 0.6 < 0.001

Independence 15.1 ± 0.5 17.4 ± 0.4 < 0.001 17.5 ± 0.4 < 0.001

Social Relationships 14.1 ± 0.7 15.5 ± 0.6 < 0.05 15.0 ± 0.6 0.06

Environment 14.9 ± 0.4 16.3 ± 0.3 < 0.001 16.1 ± 0.4 < 0.001

Spirituality 13.6 ± 0.9 14.9 ± 0.7 < 0.05 15.0 ± 0.9 < 0.05

Quality-of-Life 14.3 ± 0.4 15.9 ± 0.3 < 0.001 15.9 ± 0.4 < 0.001

presented, in average, an increase of 11.2%. A linear

fixed-effects model revealed a global states p<0.05.

When comparing each session with the first one

(Table 7), only one did not reach statistical

significance (‘social relationships’; S4; p>0.05).

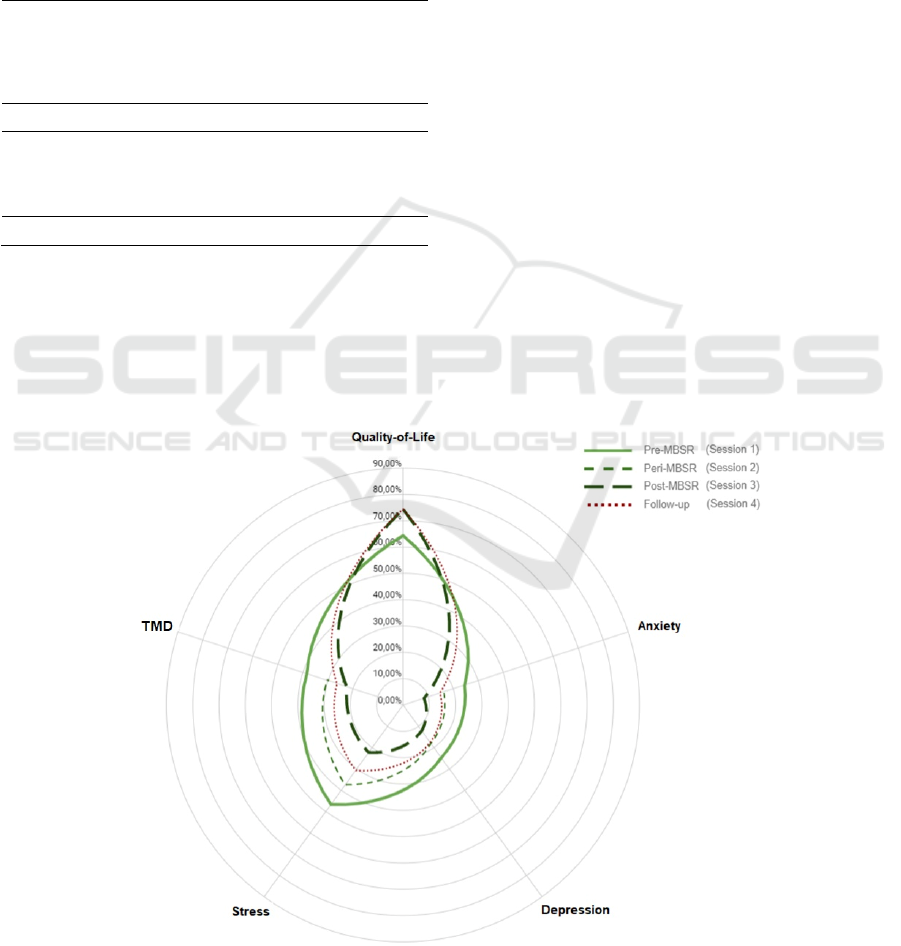

4 CONCLUSIONS

The results presented in the previous section shed

light on the temporal changes of mood and quality of

life parameters in participants enrolled in

Mindfulness meditation practice. An 11.2% in an

individual's Quality-of-Life was observed before and

after training. Furthermore, meditation practice was

associated with a decrease in the state of anxiety (-

66.0%), depression (-51.0%) and TMD (-19.0%).

Finally, stress also presented a significant reduction

post-practice, i.e., -52.0% (Table 8; Figure 5). This

longitudinal, randomized and actively controlled

study has been carried along for 18 weeks, showing a

gradual change between sessions. Regarding the

fourth session, which took place two months after the

end of the course, participants presented a trend of

regression to values close to the second session.

These results point to functional changes that regress

when the subjects stop the practice of this meditation

technique. This indicates the benefits of continued

Mindfulness meditation as an effective method for

mind calming, improving quality of life and

increasing positive emotional states. It should be

noted that the sample is mainly composed of

university students who experienced an increased

overload in the second evaluation of July, a period of

academic evaluations (Table 3). Nonetheless, even in

this stressful moment, the results revealed an evident

improvement in the subject’s well-being. Given this

limitation, it is likely that the results of the third

The Mindfulness Meditation Effect on States of Anxiety, Depression, Stress and Quality of Life

579

session are even more relevant to the individual's

well-being. Together, the findings of the current study

suggest that the daily practice of Mindfulness

meditation contributes to reducing depression,

anxiety, stress, TMD, and to increase QoL.

Mindfulness meditation benefits well-being,

potentially preventing clinical mood disturbances that

affect a large part of the population.

Table 8: Survey resume evolution of Quality-of-life,

Anxiety, Depression, Stress and TMD.

State

Survey

Pre-MBSR

(S1)

Peri-MBSR

(S2)

Post-MBSR

(S3)

Follow-up

MBSR (S4)

QoL WHOQOL 64.4 n.a. 74.4 74.4

Anxiety

DASS

24.5 16.2 8.3 14.8

Depression 24.8 18.1 12.1 17.6

Stress 46.7 37.6 22.4 30.7

TMD POMS 38.5 30.2 22.6 26.4

DECLARATIONS

Funding: The authors acknowledge the financial

support of the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia,

through its project UIDB/FIS/04559/2020.

Ethics Approval: Ethical approval for this research

was obtained from the Ethics Committee of NOVA

School of Science and Technology - NOVA

University of Lisbon, Portugal. The study was

performed following the ethical standards of the 1964

Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments.

Consent to Participate and Publication: Informed

consent was obtained from all subjects included in

this study.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that there is

no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this

paper.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank LIBPhys, Laboratory for

Instrumentation, Biomedical Engineering and

Radiation Physics, from NOVA School of Science

and Technology, for the equipment, laboratory and all

conditions provided.

Figure 5: Final states evolution in radar graph for Anxiety, Depression, Stress, TMD and QoL.

HEALTHINF 2022 - 15th International Conference on Health Informatics

580

REFERENCES

Anheyer, D., Haller, H., Barth, J., Lauche, R., Dobos, G., &

Cramer, H. (2017). Mindfulness-based stress reduction

for treating low back pain: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. In Annals of Internal Medicine (Vol.

166, Issue 11, pp. 799–807). American College of

Physicians. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-1997

Chang, S. J., Kwak, E. Y., Hahm, B. J., Seo, S. H., Lee, D.

W., & Jang, S. J. (2016). Effects of a Meditation

Program on Nurses’ Power and Quality of Life. Nursing

Science Quarterly, 29(3), 227–234. https://doi.org/

10.1177/0894318416647778

de Bruin, E. I., Meppelink, R., & Bögels, S. M. (2015).

Mindfulness in Higher Education: Awareness and

Attention in University Students Increase During and

After Participation in a Mindfulness Curriculum

Course. Mindfulness, 6(5), 1137–1142. https://doi.org/

10.1007/s12671-014-0364-5

de Vibe, M., Bjørndal, A., Fattah, S., Dyrdal, G. M.,

Halland, E., & Tanner-Smith, E. E. (2017).

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) for

improving health, quality of life and social functioning

in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Campbell Systematic Reviews, 13(1), 1–264. https://

doi.org/10.4073/csr.2017.11

Dobkin, P. L., & Hutchinson, T. A. (2013). Teaching

mindfulness in medical school: Where are we now and

where are we going? Medical Education, 47(8), 768–

779. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12200

Education, D., Health and Social Care, D., The Rt Hon

Damian Hinds, M., & The Rt Hon Matt Hancock, M.

(n.d.). One of the largest mental health trials launches

in schools - GOV.UK. Retrieved April 10, 2019, from

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/one-of-the-

largest-mental-health-trials-launches-in-schools

Evans, S., Wyka, K., Blaha, K. T., & Allen, E. S. (2018).

Self-Compassion Mediates Improvement in Well-being

in a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Program in a

Community-Based Sample. Mindfulness, 9(4), 1280–

1287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0872-1

Faro Viana, M., Almeida, P., & Santos, R. C. (2012).

Adaptação portuguesa da versão reduzida do Perfil de

Estados de Humor – POMS. Análise Psicológica,

19(1). https://doi.org/10.14417/ap.345

Galante, J., Dufour, G., Benton, A., Howarth, E., Vainre,

M., Croudace, T. J., Wagner, A. P., Stochl, J., & Jones,

P. B. (2016). Protocol for the Mindful Student Study: A

randomised controlled trial of the provision of a

mindfulness intervention to support university students’

well-being and resilience to stress. BMJ Open, 6(11).

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012300

Galante, J., Dufour, G., Vainre, M., Wagner, A. P., Stochl,

J., Benton, A., Lathia, N., Howarth, E., & Jones, P. B.

(2018). A mindfulness-based intervention to increase

resilience to stress in university students (the Mindful

Student Study): a pragmatic randomised controlled

trial. The Lancet Public Health, 3

(2), e72–e81. https://

doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30231-1

Garland, S. N., Carlson, L. E., Cook, S., Lansdell, L., &

Speca, M. (2007). A non-randomized comparison of

mindfulness-based stress reduction and healing arts

programs for facilitating post-traumatic growth and

spirituality in cancer outpatients. Supportive Care in

Cancer, 15(8), 949–961. https://doi.org/10.1007/

s00520-007-0280-5

Grossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt, S., & Walach, H.

(2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health

benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic

Research, 57(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-

3999(03)00573-7

Hilton, L., Hempel, S., Ewing, B. A., Apaydin, E., Xenakis,

L., Newberry, S., Colaiaco, B., Maher, A. R., Shanman,

R. M., Sorbero, M. E., & Maglione, M. A. (2017).

Mindfulness Meditation for Chronic Pain: Systematic

Review and Meta-analysis. Annals of Behavioral

Medicine, 51(2), 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/

s12160-016-9844-2

João Carvalho das Neves, João Pargana, M. L. (2019).

Leadership Development & Mindfulness - ISEG.

https://www.idefe.pt/cursos/LDM

Kemper, K. J., Carmin, C., Mehta, B., & Binkley, P. (2016).

Integrative Medical Care Plus Mindfulness Training for

Patients With Congestive Heart Failure. Journal of

Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative

Medicine, 21(4), 282–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/

2156587215599470

Kolahkaj, B., & Zargar, F. (2015). Effect of Mindfulness-

Based Stress Reduction on Anxiety, Depression and

Stress in Women With Multiple Sclerosis. Nursing and

Midwifery Studies, 4(4). https://doi.org/10.17795/

nmsjournal29655

Li, W., Howard, M. O., Garland, E. L., McGovern, P., &

Lazar, M. (2017). Mindfulness treatment for substance

misuse: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 75, 62–96.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2017.01.008

Manh Dang, J., Bashmi, L., Meeneghan, S., White, J.,

Hedrick, R., Djurovic, J., Vanle, B., Nguyen, D.,

Almendarez, J., Ravets, P., Gohar, Y., Hanna, S.,

Danovitch, I., & William IsHak, W. (2018). The

Efficacy of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on

Depressive Symptoms and Quality of Life: A

Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials.

OBM Integrative and Complementary Medicine, 3(2),

1–1. https://doi.org/10.21926/obm.icm.1802011

MathWorks. (2020). Fit linear mixed-effects model -

MATLAB (FITLME). https://www.mathworks.com/

help/stats/fitlme.html

McConville, J., McAleer, R., & Hahne, A. (2017).

Mindfulness Training for Health Profession Students—

The Effect of Mindfulness Training on Psychological

Well-Being, Learning and Clinical Performance of

Health Professional Students: A Systematic Review of

Randomized and Non-randomized Controlled Trials. In

Explore: The Journal of Science and Healing (Vol. 13,

Issue 1, pp. 26–45). Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.explore.2016.10.002

The Mindfulness Meditation Effect on States of Anxiety, Depression, Stress and Quality of Life

581

McNair, D. M., Lorr, M., & Droppleman, L. F. (1971).

Profile of Mood States (POMS). In Educational and

Industrial Testing Services. https://doi.org/10.1007/

978-1-4419-9893-4_68

Mouzinho, L., Costa, N., Alves, T., Silva, S., & de Lima, L.

(2018). Mindfulness Conributions on Medical

Conditions: A Literature Review. Psicologia, Saúde &

Doenças, 19(2), 182–196. https://doi.org/10.15309/

18psd190202

OECD. (2018). Health at a Glance: Europe 2018.

https://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/OECD-

Factsheet-Mental-Health-Health-at-a-Glance-Europe-

2018.pdf

Pais-Ribeiro, J. L., Honrado, A., & Leal, I. (2004).

Contribuição para o estudo da adaptação portuguesa das

escalas de ansiedade,depressão e stress (eads) de 21

itens de lovibond e lovibond. In Psicologia, Saúde e

Doenças: Vol. V (Issue 2).

Spijkerman, M. P. J., Pots, W. T. M., & Bohlmeijer, E. T.

(2016). Effectiveness of online mindfulness-based

interventions in improving mental health: A review and

meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. In

Clinical Psychology Review (Vol. 45, pp. 102–114).

Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.03.009

Tang, Y.-Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The

neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature

Publishing Group, 16. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3916

Virgili, M. (2015). Mindfulness-Based Interventions

Reduce Psychological Distress in Working Adults: a

Meta-Analysis of Intervention Studies. Mindfulness,

6(2), 326–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-

0264-0

Vos, J., & Vitali, D. (2018). The effects of psychological

meaning-centered therapies on quality of life and

psychological stress: A metaanalysis. Palliative &

Supportive Care, 16(5), 608–632. https://doi.org/

10.1017/S1478951517000931

Weare, K. (2018). The Evidence for Mindfulness in

Schools for Children and Young People. The

Mindfulness In Schools Project, July, 1–36. https://

bit.ly/2X11grY

World Health Organization. (1998). WHOQOL: measuring

quality of life. Psychol Med, 28(3), 551–558. https://

doi.org/10.5.12

World Health Organization. (2014). Basic Documents -

Constitution of WHO. http://apps.who.int/gb/bd

HEALTHINF 2022 - 15th International Conference on Health Informatics

582