Be Aware! Indications for Intercultural Awareness for Digital Health

Innovations and Innovation Capability

Lena Otto

a

, Linda Kosmol

b

, Tim Scheplitz

c

and Hannes Schlieter

d

Research Group Digital Health, Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden, Germany

Keywords: Digital Health Innovation, Dimension of National Culture, Interview Study.

Abstract: Cultural influences on single Digital Health Innovation (DHI) processes or on a society’s capability to

promote DHI development and implementation remain difficult to describe and to manage on different levels

of responsibility. Using Hofstede’s Dimensions of National Culture, we investigated the influence of each

dimension on DHI to support awareness and to derive valuable indications for both practice and research. An

expert study with 23 participants representing 13 different European countries explored the influence of a

nation’s characteristic on how the DHI domain is supported or slowed down. The results describe indications

for all six dimensions of Hofstede, but “Uncertainty Avoidance” and “Indulgence” are highlighted as the

interviewees could assess their influence on DHI confidently. Combined with cultural aspects that do not rely

on nationalities, our contribution can improve scientific and practice-oriented initiatives especially in context

of international collaborations or of DHI for multi-national usage scenarios.

1 INTRODUCTION

Digital health changes the way healthcare is delivered

by introducing “tools and services that use

information and communication technologies to

improve prevention, diagnosis, treatment,

monitoring, and management of health-related issues

and to monitor and manage lifestyle-habits that

impact health” (European Commision, 2020).

Various terms, topics or artefacts shall be

differentiated but all have the same aim: to improve

access to and quality of care and make healthcare

more efficient (European Commision, 2020).

Even though expectations regarding digital health

are high, studies show that various countries are not

equally ready or capable of implementing digital

health into their national health systems (Thiel et al.,

2019). Hence, the question is to whether there is a

common characteristic inherent in these countries

responsible for the different levels of readiness or

capability. Prior studies have investigated a variety of

barriers and enablers, i.e., influential factors to Digital

Health Innovation (DHI) processes and found that

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3814-4088

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0413-5968

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0070-4561

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6513-9017

culture is one of these (Kowatsch et al., 2019; Yusif

et al., 2017). National culture also has a big influence

on innovation capability, which in turn can increase

the competitiveness of a country (Prim et al., 2017).

Based on these findings, the question arises to what

extent DHI processes are influenced by culture.

Culture can be defined in many ways, but

Hofstede’s definition by using 6 dimensions to

describe a national culture is perhaps the most

popular one and commonly used (Hofstede et al.,

2010; Srite and Karahanna, 2006). The framework of

Hofstede has been applied by many researchers to

investigate a variety of domains. In particular, it has

been studied how culture influences the degree of

innovation of countries (Moonen, 2017; Prim et al.,

2017), the innovative strength of businesses (Gallego-

Álvarez and Pucheta-Martínez, 2021) or the

technology acceptance of a nation (Srite and

Karahanna, 2006).

The influence of culture in the domain of

healthcare has been partially investigated, e.g., by

integrating the cultural dimensions of Hofstede into

the Technology Acceptance Model or the Unified

Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology to

Otto, L., Kosmol, L., Scheplitz, T. and Schlieter, H.

Be Aware! Indications for Intercultural Awareness for Digital Health Innovations and Innovation Capability.

DOI: 10.5220/0011009900003123

In Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2022) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 801-811

ISBN: 978-989-758-552-4; ISSN: 2184-4305

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

801

explain eHealth or telemedicine adoption and use

(Hoque and Bao, 2015; Nwabueze et al., 2009).

Nevertheless, these studies investigate cultural

influence in the healthcare systems primarily from the

patient or technology user perspective rather than

from a systemic view of innovation in healthcare.

Braithwaite et al. applied cluster analysis to

investigate the cultural influence on the performance

of health systems in certain OECD countries and

conclude that cultural characteristics play an

important role on this performance (Braithwaite et al.,

2020). However, they focus on the performance of

health systems in general and not on DHI capability.

Hence, we want to understand how and to what

extent culture affects DHI processes and,

consequently, a society’s capability to promote DHI.

This supports learning about differences between the

state of DHI and provide new research questions that

may result in further evidence in best practices. Our

understanding of the term “DHI” is thereby process-

oriented, as cultural aspects influence the way of how

an innovative digital health artifact is designed,

developed and implemented. We see five scenarios

within the context of scaling DHI projects which are

affected by cultural differences and, thus, may benefit

from our investigation:

Management of DHI projects for international

usage contexts

Management of DHI projects with

cross-boarder collaborations

Interpretation and adaption of best practices

from different countries

Design and management of international DHI

spaces and programs

Supporting the National policy making in

developing and managing the legal framework

for DHI implementation

Therefore, our research lies at the intersection of

three topics: (digital) health, (digital) innovation, and

culture. Conclusively, the following research

question arises: How do a country’s characteristics of

national culture influence DHI processes regarding

and the related structure in DHI environments?

To analyze this influence, we conducted a

qualitative analysis. We held interviews with 23

experts from 13 European countries to get deeper

insights into their health system’s structure and

innovation processes. This explorative approach was

deemed feasible as the influence of culture on the

structure and innovation capability of healthcare

1

https://www.hofstede-insights.com/product/culture-

compass/

systems is not yet a well-investigated topic. We

provide descriptive findings in this paper and enrich

the knowledge base around healthcare systems and

their structure with a focus on cultural factors and

DHI. This lays the groundwork for further studies

investigating that topic in detail, which can derive

recommendations for best practices on how to handle

especially internationalization in digital health.

2 FUNDAMENTALS

2.1 Dimensions of National Culture

Culture can be defined in many ways, either based on

shared values or problem solving, or by using other

all-encompassing definitions (Straub et al., 2002).

Hofstede’s definition is “arguably the most

predominantly used” (Srite and Karahanna, 2006).

According to Hofstede, “culture is the collective

programming of the mind that distinguishes the

members of one group or category of people from

others” (Hofstede, 2011). Various patterns and

dimensions exist to describe the facets of culture

(Straub et al., 2002), with Hofstede’s dimensions of

national culture being most frequently used.

Hofstede describes national culture by using six

dimensions (Hofstede et al., 2010): Power Distance,

Uncertainty Avoidance, Individualism vs.

Collectivism, Masculinity vs. Femininity, Long-

Term vs. Short-Term Orientation, and Indulgence vs.

Restraint. These dimensions depict how a society’s

culture affects the value and behavior of its members.

They are briefly described in Table 1. Based on these

dimensions and through multiple cross-national and

replication studies, Hofstede and other colleagues

have generated a dataset that contains the value scores

for the cultural dimensions for 111 countries and

regions around the world. As this data set is provided

on Hofstede’s website, it is eagerly used for further

research, despite criticism and discussion (Gaspay et

al., 2009). In the following, the Hofstede dimensions

are briefly described as per the Culture Compass, and

as communicated to our study participants. The

Culture Compass

1

is a questionnaire to assess an

individual's scores regarding the cultural dimensions.

2.2 Prior Research

Some previous studies already identified an influence

of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions on the degree of

Scale-IT-up 2022 - Workshop on Scaling-Up Health-IT

802

innovation in certain countries, that we like to

investigate further within the domain of DHI. For

instance, Prim et al. analyzed the influence of cultural

dimensions on the degree of innovation in general

(Prim et al., 2017). They found a negative relation for

PDI and a positive one for IDV.

Other authors investigating the role of Hofstede’s

cultural dimensions on (IT) adoption and innovation

also concluded that a high PDI has a negative (Halkos

and Tzeremes, 2013; Thatcher et al., 2003) and a high

IDV a positive effect on the degree of innovation

(Moonen, 2017; Yaveroglu and Donthu, 2002).

Table 1: Dimensions of national cultures (Hofstede et al.,

2010).

PDI A high value of Power Distance indicates a high

acceptance of power being distributed unequally

within a society; hierarchy is needed rather than

just being a convenience.

Societies with a low

score in the PDI dimension put emphasis on the

importance of equal rights, as opposed to the

importance of privileges of the more powerful

one.

UAI A high value of Uncertainty Avoidance

indicates a need for predictability and structure,

often in the form of written and unwritten rules.

Societies scoring low in the UAI dimension

consider uncertainty as normal and each day is

taken as it comes.

IDV In societies with a high score in the

Individualism dimension, there is a strong sense

of "I", meaning that one’s personal identity is

distinct from others’. In collectivist societies

(low score in IDV), there is a strong sense of

"we", illustrating a mutual practical and

psychological dependency between the person

and the in-group.

MAS In societies with a high score in the Masculinity

dimension, people tend to focus on personal

achievement, material success and the

importance of status. In feminine societies (low

scores), people are more concerned with quality

of life, taking care of those less fortunate,

ensuring leisure time, and finding consensus.

LTO Societies with a high score in the Long-term

Orientation dimension, focus on perseverance

and thrift. Short-term oriented societies (low

scores) emphasize respect for traditions and

fulfilling social obligations.

IVR Societies with a high score in Indulgence

dimension reflect a positive attitude and the view

that one can act as one pleases. In contrast, in

restraint societies (low score) gratification of

needs is regulated by strict social norms and

leisure is less important.

Also, the dimensions of MAS and UAI were

already found by other authors to be negatively

related to the degree of innovation (Halkos and

Tzeremes, 2013; Prim et al., 2017), while Moonen

sees this negative connection only during the

initiation phase of innovations, while a higher level of

masculinity can be positively influencing when

implementing innovations. Halkos and Tzerenes

underline that the environment of innovations is often

uncertain which is especially contradictory in

countries with a high score of UAI (Halkos and

Tzeremes, 2013). Moonen and Prim et al. showing

that planning and optimism can be very supportive

not only for innovations in general but also for DHIs

and postulate a positive influence of LTO and IVR

(Moonen, 2017; Prim et al., 2017).

2.3 Initial Indications of Influence

To gain insights into the status of DHI capability in

different countries and whether or how this is linked

to Hofstede's cultural dimensions, we related the

country-specific scores of the Hofstede dimensions

(values from 2015) to the country-specific values of

the Digital Health Index (DH Index, values from

2018) by the Bertelsmann foundation (Thiel et al.,

2019). We examined whether and to what extent the

values correlate with the Hofstede values. Hofstede

scores were available and originally marked as valid

for all 17 countries ranked within DH Index. Table 2

presents the results of our analysis. The only

significant correlation with the DH Index is regarding

MAS. We interpreted this correlation only as first

indication for our further research activities.

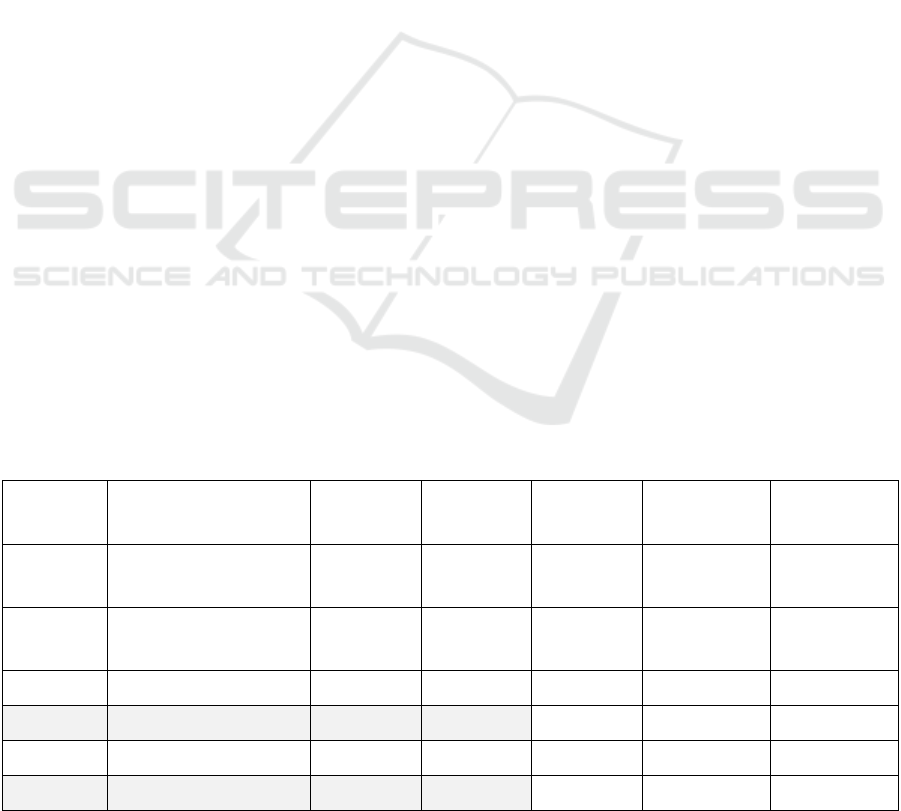

Table 2: Correlation analysis - dimensions of national

culture and DH Index; significance highlighted in grey.

Dimension Correlation & Si

g

nificance

PDI Corr: -0,40;

p

-value: 0,103

IDV Corr: -0,05;

p

-value: 0,841

MAS Corr: -0,48;

p

-value: < 0,05

UAI Corr: -0,37;

p

-value: 0,140

LTO Corr: -0,27;

p

-value: 0,295

IVR Corr: 0,19;

p

-value: 0,468

Although the amount of research on the influence

of Hofstede’s dimensions of national culture on DHI

processes and capability is scarce, there are previous

studies that identified and described their influence on

innovation capability in general. Prim et al. found a

negative relation for PDI and a positive one for IDV

(Prim et al., 2017). Other authors investigating the

role of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions on (IT)

Be Aware! Indications for Intercultural Awareness for Digital Health Innovations and Innovation Capability

803

adoption and innovation also concluded that a high

PDI has a negative (Halkos and Tzeremes, 2013;

Thatcher et al., 2003) and a high IDV a positive effect

on the degree of innovation (Moonen, 2017;

Yaveroglu and Donthu, 2002).

Also, the dimensions of MAS and UAI were

already found by other authors to be negatively

related to the degree of innovation (Halkos and

Tzeremes, 2013; Prim et al., 2017), while Moonen

sees this negative connection only during the

initiation phase of innovations and a positive relation

when implementing innovations (Moonen, 2017).

Also, a positive influence of LTO and IVR have

been stated in general as planning and optimism is

highlighted as very supportive for innovation projects

(Moonen, 2017; Prim et al., 2017).

3 METHODS

Drawing on the initial, quantitative indications, we

approached the study of the relationship between

dimensions of national culture and DHI in an

explorative, qualitative way. We followed this

approach with expert interviews, as literature on the

influence of culture on digital health innovation

processes and on healthcare system’s digital health

capability is scarce. The aim was to get a diverse

picture on European countries, which rank different

in the culture dimensions, to investigate the

relationship between culture and DHI.

3.1 Study Design

The expert interviews followed a semi-structured

interview guide supplemented with additional

questions for clarification, examples, and deeper

insights. The interview guide included three parts.

The 1st part involved organizational matters, e.g.,

consent to recording of the interview and questions

about the interviewee, such as working experience

and current position in the healthcare system.

In the 2nd part, the interviewees were asked about

the structure and innovation processes of their

country's healthcare system and their understanding

of how digital innovation is introduced. Questions

related to these two topics were, e.g. “Who are the

main actors driving DHIs in your country?”, “What

strengths of the people/the healthcare system enable

DHIs?”, or “Do DHI ecosystems exist?”.

2

Scores available via https://geerthofstede.com/research-

and-vsm/dimension-data-matrix/

The 3rd part focused on the central part: cultural

influence on the healthcare system. The interviewees

were asked about characteristic traits, strengths and

trust into the government that may influence the

healthcare system and how innovation takes place in

that domain. Afterwards, the Hofstede values for each

country as well as the individual Culture Compass

results served as a basis to investigate how the

dimensions may influence the country's health system

structure and digital health innovation capability. The

country scores of each cultural dimension were

categorized as being very low, low, average, high, or

very high, compared to the distribution of all

Hofstede country scores. Each interviewee was given

this categorization and a description of what it means

according to Hofstede. Afterwards, they could

subjectively assess if they feel this is true for their

country and if it has an impact on how the healthcare

system is structured or how DHI processes happen.

Also, all experts were asked if best practices from

healthcare systems in other countries are only

imported from countries that are similar or if the

healthcare system’s structure of the other country is

not relevant for adopting best practices. The aim of

that was to analyze if structural or cultural similarity

makes it easier to learn from each other.

3.2 Participant Selection

To obtain a diverse picture of European countries, we

looked for participants with national backgrounds

that scored both minimal and maximal for each of the

six cultural dimensions

2

. For each dimension, two

countries were selected that are among the five

highest or the five lowest scoring countries in this

dimension. In selecting, countries with more than one

extreme value among the culture dimensions were

prioritized. For example, Denmark has one of the

lowest scores in PDI, MAS, UAI, and LTO, and one

of the highest scores in IVR. Similarly, the scores of

Romania are among the highest for PDI and among

the lowest for IDV and IVR. Another aspect for

country selection was the diversity between

geographic parts of Europe. We aimed to include at

least two countries per part of Europe.

Interviewees in each country were contacted via

two big European networks focusing on DHIs and/or

digital health ecosystems as they were expected to be

experts for their country’s health systems. Those

networks are the European Innovation Partnership on

Active and Healthy Ageing (EIP on AHA) and the

Scale-IT-up 2022 - Workshop on Scaling-Up Health-IT

804

European Connected Health Alliance (ECHAlliance).

In both networks, key stakeholders were contacted via

mail to recommend suitable interview partners in each

of the selected countries. The goal was to interview two

experts per country, which is why the interviewees

were also asked to suggest further experts in their

country with a position different from their own one.

To analyze the answers given by each interviewee in

the right context, all participants were given access to

the Culture Compass survey with an individual code.

The results mirror the background of each interviewee

more specifically than the general country scores.

3.3 Interview Conduction

The interviews were conducted in February and

March 2021 in the form of online video conferences,

which mainly lasted around an hour of time. In total,

23 persons (11 women, 12 men) were interviewed.

The goal of two interviews per country was reached

in ten countries: Belgium (one interview for the

Dutch-speaking Flemish, one for the French-speaking

Walloon part), Croatia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland,

Germany, Greece, Italy, Portugal and the United

Kingdom (one interview for Northern Ireland, one for

Scotland). For Norway, Romania, and Slovakia only

one expert was willing to participate in our study.

Alongside with the interviews, publicly available

data on the healthcare system was used to obtain

additional insights. All interviewees, except for one,

had at least five years of experience in the healthcare

sector. All of the interviewees had a health-related

background, seventeen additionally had an IT-related

background, and nine of the seventeen had an

innovation background on top. Also, the

organizational background of all 23 interviewees was

quite diverse, ranging from employees of

governmental authorities, network organizations or

universities to healthcare providers and consultants.

3.4 Interview Analysis

All responses were analyzed across all interviews

according to the specific questions. We checked for

relationships between the cultural scores and

responses, e.g., if the existence of digital health

ecosystems or the trust in government are dependent

on certain cultural characteristics. Additionally, the

perceived influence of each cultural dimension on the

innovation structure or capability were analyzed

across all interviews to receive an overall statement

per dimension.

4 RESULTS

Below, we lay out what impact the Hofstede

dimensions had on innovation in the national

healthcare system as perceived by the interviewees.

Table 3 summarizes whether a relationship was seen

and interpreted as being positive or negative.

Especially for the PDI and IDV dimension, a

beneficial or detrimental influence on DHI of a high

or low score might depend on the phase of the

innovation, e.g., initiation or implementation. This

distinction arises primarily from the main actors in

the two phases: while start-ups, companies or

researchers are more likely to be the driving force

during the creative initiation phase, implementation

in the health sector requires governmental authorities

(e.g. for a national roll out of DHIs).

Table 3: Correlation perceived by the interviewees regarding Hofstede’s dimensions of national culture and DHI capability.

Stated positive or negative relationships highlighted in grey for further discussion.

Dimension Overall Positive Negative Part-part No correlation I don’t know

PDI

Depends on the step in

the innovation process

4 8 4 2 5

IDV

Depends on the step in

the innovation process

4 6 2 1 10

MAS Weak negative 2 6 0 1 14

UAI Negative 0 13 1 0 9

LTO Weak positive 7 2 0 3 11

IVR Positive 13 1 0 1 8

Be Aware! Indications for Intercultural Awareness for Digital Health Innovations and Innovation Capability

805

In the following, the results per dimension with

the feedback and thoughts of the experts are presented

more in detail. We rearranged the order of

presentation to: first, discuss MAS as this is the only

dimension that correlates directly with DH Index

;

second, focus on UAI and IVR as these dimensions

were commonly assessed influential by the experts;

and last, complete the overview of interview results

with selected impressions of the remaining

dimensions PDI, IDV and LTO.

4.1 Masculinity (MAS)

The dimension MAS was associated with caring,

status, position, quality of life, and well-being. To

counteract the problem of this dimension being often

linked to gender roles (Gaspay et al., 2009), we have

only paraphrased this dimension in the interview, but

not mentioned it by name. The majority of the

interviewees, 14 out of 23, did not know how to

interpret MAS in the context of DHI. The

interviewees remarked that the healthcare system is

generally oriented toward the common welfare in

terms of structure and goals, thus inherently feminine

and caring for people. Looking at the individual

actors in the healthcare domain, e.g., doctors or

politicians, a high MAS was considered rather

obstructive, especially for the implementation of

DHIs, since the pursuit of status of the individual may

be in opposition to the idea of the common good.

4.2 Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI)

The dimensions UAI and LTO were difficult to

delineate, but we try to focus on each dimension

separately. UAI was associated with system structure,

regulation, risk taking, predictability, and in the

health context strongly with evidence. The

interviewees identified an almost exclusive negative

relation between UAI and DHI capability. Reasons

for that are that a high UAI slows down innovation

due to falsely assumed security (GER), and that a

“need for stability may disrupt innovation” (SLK)

because “in order to accept innovation you need to

accept uncertainty” (ITA). Other feedback was also

related to the individual context in each country, e.g.,

that in Denmark, due to a good social security system,

risks can be taken, people are not afraid of risks and

thus can drive innovation (DEN).

Over all interviews, the experts expressed that

UAI itself may hinder innovation as it leads to people

not taking risks and not focusing on change.

However, they also expressed that security is nice to

have on the personal level. Some healthcare

specificities also affect this dimension, as the

healthcare sector immanently requires certainty in

terms of evidence-based medicine and is strongly

structured and highly regulated. By highly regulating

it, the healthcare sector tries to give security and

stability. However, this should not go too far, as an

Estonian interviewee mentioned: “Healthcare is

moving to […] a more regulated field […], but on the

other hand you can’t go too far with the rules because

every person is an individual and there are so many

variables when you make treatment or diagnostic

decisions that you can’t describe all rules”.

All in all, there seems to be a negative relation

between UAI and the DHI capability.

4.3 Indulgence (IVR)

IVR was associated with how optimistic people in

each country are and how far they are open for new

things/innovations and are not afraid to fail in the area

of innovation. This was considered for the initiation

and implementation phase alike. The IVR dimension

was not very much commented on but more than half

of all interviewees (n=13) saw a positive connection

between IVR and innovation.

The statements of the interviewees fully support

the quantitative results, namely that there is a strong

positive relation between IVR and innovation in

healthcare, i.e., the higher a country’s IVR the higher

its degree of innovation in digital healthcare

4.4 Statements on Other Dimensions

4.4.1 Power Distance (PDI)

PDI was particularly associated by the interviewees

with hierarchies, communication opportunities and

information flows with stakeholders of DHIs, and

national or regional governmental regulations in

general. Regarding the effect of PDI, eight

interviewees indicated that PDI and innovation are

negatively correlated as it was associated with few

opportunities for entrepreneurs as well as limited

participation and communication flows. On the other

hand, four interviewees felt that strong hierarchies are

helpful for DHIs, as they can drive and support

innovation from the top.

Another four interviewees differentiated between

the impact of PDI on innovation initiation and

innovation implementation. A low PDI was perceived

as beneficial in the initiation phase, but for

implementation a higher PDI was considered more

advantageous. A lower PDI is perceived better for

Scale-IT-up 2022 - Workshop on Scaling-Up Health-IT

806

initiation and creativity regarding DHIs as “[low PDI

results in] flat hierarchies that give people the ability

to think, you encourage them and that helps [DHI]”

(BEL-Flanders) and “you get feedback and support”

(DEN). A “[high PDI] makes it harder to innovate,

harder to implement a solution because success is

affected by your position in the hierarchy” (CRO).

This is also reflected by some respondents who

indicated that the country’s innovation processes are

either bottom-up or bottom-up in combination with a

top-down approach, but not exclusively top-down.

In terms of DHI implementation, a higher PDI

was considered better since it may speed up decision-

making and implementation processes due to less

discussions, "it is just decided, we will do it this way"

(GER). Moreover, in the healthcare domain “no

innovations were successful that have not been given

blessing by higher level decision-makers” (CRO)

implying the need for governmental support.

Additionally, some interviewees concluded that

an average value, something in between strong and

flat hierarchies, is the worst for DHI initiation and

implementation, as it neither fosters innovation

through consensus nor enforcement.

Further, we observed that countries with existing

or developing DHI ecosystems tend to have a lower

or average PDI value which may suggest that the

value of networks is more likely to be recognized in

countries with a low PDI.

4.4.2 Individuality (IDV)

The dimension IDV was associated with creativity,

entrepreneurship, forerunners/leaders, teamwork,

collaboration, and group dependency vs. a focus on

an individual. As with PDI, in different phases of DHI

different IDV traits were considered necessary by the

majority of the interviewees. A higher IDV was

perceived to be better for initiating DHIs as

“innovation needs to be started by strong individuals”

(CRO) and a high IDV was linked to innovative

forerunners, albeit "[too high IDV] might prevent

working in a team and this is crucial for innovation

[implementation]” (BEL-Flanders). Hence, a lower

IDV was regarded as helpful for implementation, i.e.

the rollout of DHIs, because forerunners with ideas

will have to work in groups or be supported by groups

to reach broader mass, acceptance, and consensus and

actually implement DHIs (DEN). The need for groups

or network thinking also became clear as many of the

interviewees' countries increasingly rely on or have

defined the emergence of ecosystems in the

healthcare sector as a goal. 17 of the 23 experts

reported that they either have several ecosystems

mainly on the regional level or one central one

already in place or are currently working on it.

4.4.3 Long-term Orientation (LTO)

The dimension LTO was often associated by the

interviewees with legislation (periods), regulation

and predictability. Many interviewees expressed the

political uncertainty regarding rules as related DH

strategies are highly dependent on the governance

periods (BEL-Flanders, CRO, EST). This was also

expressed as a sector-specific aspect as healthcare is

highly influenced by the government, regarding the

regulation but in some countries also regarding

financing and research funding. Another aspect

related to the dependence on legislation periods is

political will, which needs to be present to bring DHI

forward (“You need political will to make this all

happen” (FIN) and "[it is] not a question of regulation

but political will" (POR)).

Even though eleven interviewees were uncertain

regarding a possible relation, seven saw a positive

relation, two a negative one and three saw no relation

at all. Reasons for seeing a positive relation were that

it would be better for the healthcare sector and DHIs

if regulations and agendas would last longer than one

legislation period as this would increase the

plannability for all stakeholders, which in turn

supports the innovation capability. Even though the

administration in some countries works on long-term

strategies or visions, this is in some countries still

subject to change when a new minister comes in

(BEL-Flanders). A similar observation was made in

Greece: A stronger focus more on the long-term is

needed and ”we [Greeks] have strategies, but in

practice actions are guided by where the money is”.

In other countries, such as Estonia, “strategies are not

changing with the governments”. From some experts,

a negative relation was seen as in that people may

stick to the status quo when LTO is high, which in

turn hinders innovation (GER).

Based on the qualitative results, we cannot fully

confirm but like to call a tendency towards a positive

relation between LTO and the DHI capability.

4.5 System Comparisons

In planning the interview, we expected to see an

influence between cultural characteristics and best

practices from other countries that are adapted and

implemented. Our expectation was that countries

rather look into countries with a similar system and,

even if not directly intended, with comparable

cultural dimension scores to get inspiration or adapt

Be Aware! Indications for Intercultural Awareness for Digital Health Innovations and Innovation Capability

807

best practices. However, the qualitative results could

not support this view. Only in some countries, the

focus is on similar structures but not necessarily on

the country-level. In Slovakia, for example, Scotland

is taken as an example as they are similar in size of

population and structure of the system. Another

example is Belgium where Netherland and France are

looked at as they both have a Bismarck system and

are closely related to Belgium. Also, Switzerland is

looked at as it also has different cultures within one

country like Belgium. In general, the experts stated

that – no matter how similar or diverse a country’s

structure or healthcare system is compared to others

– each best practice from another country needs to be

“translated” to the specific national conditions. The

focus is on “pick and change” (BEL-Flanders), which

is mostly done on a small-scale level (e.g. region or

municipality rather than country level) as pointed out,

e.g., by experts from Estonia, Germany, United

Kingdom and Italy.

5 DISCUSSION

Based on the qualitative results, we have found

valuable indications about how Hofstede’s

dimensions of national culture influence DHI

processes and/or DHI capability of societies. We

could therefore confirm the importance of cultural

factors for the area of DHIs and support the thesis that

“an understanding of culture is important to the study

of information technologies (IT) in that culture at

various levels, including national, […] can influence

the successful implementation and use of information

technology” (Leidner and Kayworth, 2006).

Regarding the main usage scenarios of intercultural

awareness stated in the introduction, we provide in

the following practical and scientific implications.

5.1 Implications for Research

With our study we contribute to the knowledge base

regarding the influence of national culture focused on

DHI processes and capability. Our indications lay the

groundwork for further studies especially for

hypothesis building that can help beneficial

investigations for increasing the DHI capability in

healthcare systems worldwide.

Our findings do not provide final evidence on

whether or how a single dimension of national culture

influence DHI processes or capability. Regarding our

observations and argumentation above, we’d rather

like to highlight MAS, UAI and IVR as dimensions

for further research. MAS and UAI are two

dimensions that seem to have a negative influence on

the degree of innovation in general and also in the

digital health area. IVR was seen as having a positive

influence not only on innovations in general but also

on the innovation capability in digital healthcare, i.e.,

the more optimistic the people in a country and

healthcare system, the easier new innovations are

initiated and implemented. In contrast to our

approach, further investigations should more focus

these dimensions to foster evidence on their influence

and interdependencies. We therefore recommend to

precise hypotheses or research questions by content

but extent the number of participants or interviewees

for a proof our indications.

Based on further large-scale studies including

other countries worldwide, best practices could be

identified between certain countries belonging to one

cultural cluster as it has been done by Braithwaite et

al. for the performance of health systems (Braithwaite

et al., 2020). Our study only laid the groundwork into

this direction by identifying correlations, which are

partially different for certain phases in the innovation

process. A deeper analysis of the various phases of

the DHI process could reveal finer granular results.

Based on this, precise recommendations could be

derived in how far each of the phases can be

supported best depending on in which country the

innovation takes place.

Another finding of our study was that best

practices from other countries are rather found and

implemented on a regional, not on a national level.

This is also underlined by initiatives such as EIP on

AHA, where certain regions across Europe are

connected to share their experiences and knowledge.

The structures of national healthcare systems may be

too diverse on a national but more similar on a

regional level. This could also be further investigated

in future studies if there are sub-cultures within

several countries which are more similar at this

regional than on the national level and can therefore

be considered when getting new impulses for

improving the healthcare system and its innovation

capability regarding digital health.

5.2 Implications for Practice

When starting the study, our hypothesis was that DHI

ecosystems can support the successful long-term

implementation of digital health innovations and thus

a society’s DHI capability but that the existence of

such ecosystems is dependent – among others – on

cultural aspects. With our study, we could generally

confirm our assumption and found indications for a

detailed and differentiated view on those cultural

Scale-IT-up 2022 - Workshop on Scaling-Up Health-IT

808

aspects. Our investigation highlights thereby

Hofstede’s dimensions MAS, UAI and IVR but does

not reject the other dimensions. Rather, we argue that

MAS, UAI and IVR might be a suitable starting point

for increasing cultural awareness activities and

discussions. In harmony to our motivation, we would

like to promote the use of our indications in practice

for: I) Analysis of multi- or international usage

contexts of upcoming DHI projects to adjust

requirements of DHI artefacts or innovation process

models; II) Management purposes of international

collaboration for DHI projects to improve internal

project organization; III) Interpretation and adaption

of “best practice” and “lesson learned” description or

case study research; and IV) Design and conduction

of international DHI initiatives and programs that

seek to support DHI knowledge exchange or to build

international data or innovation spaces.

While technological progress will continue

dynamically, established structures of health systems

(e.g., its segmentation, regulation and administration)

are rough to change simultaneously due to their

linkage to national culture. International intended

DHI projects or programs should not underestimate

the task of bridging such gaps. In Slovakia, for

example, the innovation-driving health insurance

company is private, which leads to implemented DHI

but also lacks in accessibility to society (only for

ensured people). A similar case could be found in

Germany, where pilots are financed by various health

insurance agencies and only people insured by the

respective agency are then able to use them. In

Croatia, old-fashioned laws affecting DHIs can be

interpreted flexible, which supports DHIs, while the

peer pressure from other countries further boosts the

initiation and implementation of DHIs. The system in

the United Kingdom, in turn, supports DHIs by its

segmentation. As a national health system exists for

each member state, networking is easy as each system

is autonomous and relatively small, so that the actors

involved know each other what enables collaboration.

Differences in the presented dimensions of

national culture may have led to structural country-

specific aspects that were also noted by the

interviewees. For example, the Greek interviewees

also highlighted financing is a crucial element.

Greece relies heavily on EU funding and may hence

have less “in-house” structures to support DHIs than

other countries. Also, dimensions of national culture

may be influenced the development of digital

infrastructures (EST), the level of education and

innovation mentality (NOR) or principles of equity

and equality (FIN) that do now positively influence

ongoing and upcoming DHI progress. On the

contrary, the Romanian interviewee expressed a

general mentality to settle with things and to lower

consequently the desire to pursue the new which can

also hinder innovations in general. Additionally, one

German expert expressed that Germans trust in

regulations and are only seldomly pragmatic, which

can negatively influence the speed of innovations.

Those longitudinal dependencies of cultural aspects

leading to structures and phenomena and again

leading to positive or negative DHI influence factors

are scientifically investigated as “path dependencies”

(Arthur, 2021) and should also be more considered in

practice-oriented discussions of international DHI

projects or programs.

Two additional thoughts mentioned by a Belgium

and a Romanian expert should complete this practical

implication section. First, the case of Belgium

showed that culture and (innovation processes in) the

healthcare system can differ vastly even within one

country. Even though the Flemish and the Walloon

system together with Brussels form Belgium, there

are different cultures and (healthcare) systems in

place in each region. Thus, our implications regarding

“international cultural awareness” could also be

valuable for intranational DHI projects or programs

under specific circumstances.

Second, the Romanian interviewee expressed that

culture does not seem to play a major role for the

innovation capability in the healthcare system of

Romania. Rather, missing leaders and money are the

most important problems that need to be solved to

focus more strongly on DHIs. “Even if you had all

this mentality and all these other aspects [positively

influencing cultural factors], if you don’t have the

money to buy an aspirin, […] you can dream a lot but

it is pretty much impossible to do the innovation.”

Thus, our presented implications might be very

helpful but should be reflected with the inclusion of

other, directly noticeable issues.

5.3 Limitations

Our study is limited in three areas, the usage of

Hofstede’s dimensions of national culture, the

conducted qualitative analyses and the influence

further cultural perspectives beyond nationalities.

The six cultural dimensions of Hofstede are not

the only concept that can be used for describing

cultures on a national level and are also subject of

criticism and discussion (Gaspay et al., 2008). Other

dimensions are, e.g., monochronism vs. poly-

chronism (Hall, 1976) or locus of control (Smith et

al., 1995). The former describes if there is a focus

rather on performing one or several activities in

Be Aware! Indications for Intercultural Awareness for Digital Health Innovations and Innovation Capability

809

parallel and the latter if one’s own life is seen as being

controlled external or internally (Leidner and

Kayworth, 2006). However, Hofstede’s dimensions

are often used and can easily be applied to one’s own

research as the country scores and the Culture

Compass are publicly available. As these dimensions

are widely used, they also enable a comparison

among studies conducted by different researchers.

Also, the qualitative study contains some

limitations. Although we had a number of

interviewees with different professional as well as

cultural backgrounds, the statements collected remain

a sample of experiences that may not be

representative in a certain country. We aimed to take

personal bias and the character traits of our

interviewees into account by applying the Culture

Compass and involving two persons per country, but

a differentiation between an individual experience

and group opinion/national culture remains difficult.

Also, our study focused exclusively on European

countries and is therefore limited to these countries.

Further large-scale studies are needed in future work

to confirm the results also for other countries.

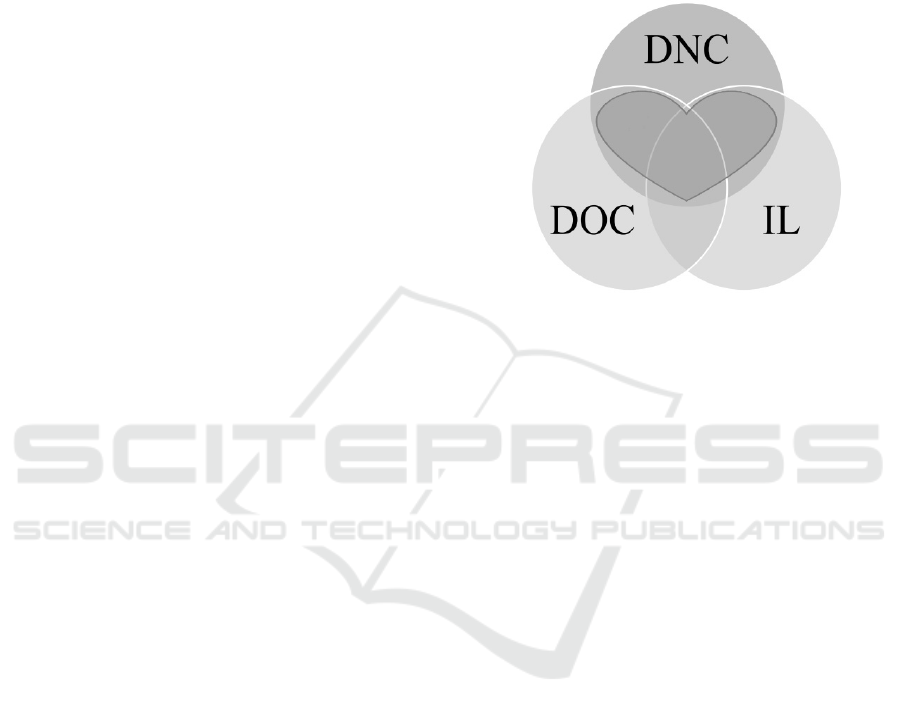

Our study focuses on differences between

national cultures. However, "cultural" factors

influencing the success of DHI processes and the DHI

capability of societies can also be stated from other

perspectives. Broaden the realm of cultural

influences, we see that the need of interdisciplinarity

and interorganizational collaboration in initiating,

conducting, and implementing digital health artifacts

cause further cultural influence factors. Thus, other

concepts next to the Dimensions of National Culture

(DNC) used in this paper should be added to ensure a

comprehensive understanding of intercultural

awareness. With the Dimensions of Organizational

Culture (DOC), Hofstede also offers an

organizational view and describes similarities and

differences between organizations by their values,

rituals, heroes, symbols and practices (Hofstede

Insights, 2020). Interdisciplinarity or

interprofessional collaboration might be addressed by

the concept of Institutional Logics (IL) that can be

used to describe the pluralism of values, logics and

behavior from medical, business, legal or

technological standpoints (Berente et al., 2019;

Hansen and Baroody, 2020; Thornton et al., 2012).

We therefor want to motivate both research and

practice of DHI to use our indications of international

cultural influence factors under consideration of these

overlaying concepts. Figure 1 illustrates the

interconnection of cultural perspectives by nations

(DNC), organizations (DOC) as well as disciplines

(IL) and highlights the “heart” of international

cultural awareness in relation to other cultural

influences. We suggest, that discussions about

culture-related phenomena in the digital health

domain should seek to clarify the spot within this

heart for each phenomenon as influences of DNC,

DOC and IL may occur simultaneously and

interdependently, but rarely equilibrated.

Figure 1: Overlaying concepts for intercultural awareness.

6 CONCLUSION

In our expert study, we discussed the influence of

Hofstede’s dimensions of national culture on DHI and

a DHI capability. Our findings provide indications on

how practice and research should be aware of each

dimension to promote DHI processes or DHI

capability. Due to our findings, Uncertainty

Avoidance seems to influence DHI projects

negatively while Indulgence have been interpreted as

a positive influence factor. Power Distance and

Individualism might influence DHI differently

depending on the development stage of a DHI. Long-

term Orientation was assessed as generally

supportive while rapidly changing circumstances

challenge this characteristic. Even though

Masculinity correlates negatively with the DH Index

of a previous Bertelsmann study, our findings could

not clarify this numeric indication conclusively.

International collaborations or DHI for multinational

usage contexts should primarily benefit of our

contribution under consideration its limitations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is part of the EFRE-funded project

“Häusliche Gesundheitsstation”. We especially like

to thank our project partners, supporters and study

participants to ensure the presented research.

Scale-IT-up 2022 - Workshop on Scaling-Up Health-IT

810

REFERENCES

Arthur, W. B., 2021. Foundations of complexity

economics. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 136–145.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s42254-020-00273-3

Berente, N., Lyytinen, K., Yoo, Y., Maurer, C., 2019.

Institutional logics and pluralistic responses to

enterprise system implementation: a qualitative meta-

analysis. MIS Q. 43, 873–902. https://doi.org/

10.25300/MISQ/2019/14214

Braithwaite, J., Tran, Y., Ellis, L.A., Westbrook, J., 2020.

Inside the black box of comparative national healthcare

performance in 35 OECD countries: Issues of culture,

systems performance and sustainability. PLOS ONE

15, e0239776. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.02

39776

European Commision, V., 2020. eHealth: Digital Health

and Care [WWW Document]. Public Health - Eur.

Comm. URL https://ec.europa.eu/health/ehealth/

home_en (accessed 11.9.21).

Gallego-Álvarez, I., Pucheta-Martínez, M.C., 2021.

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and R&D intensity as

an innovation strategy: a view from different

institutional contexts. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 11, 191–220.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-020-00168-4

Gaspay, A., Dardan, S., Legorreta, L., 2009. “Software of

the Mind”-A Review of Applications of Hofstede’s

Theory to IT Research. J. Inf. Technol. Theory Appl.

JITTA 9, 3.

Gaspay, A., Dardan, S., Legorreta, L., 2008. “Software of

the Mind” - A Review of Applications of Hofstede’s

Theory on IT Research. J. Inf. Technol. Theory Appl.

9, 1–37.

Halkos, G.E., Tzeremes, N.G., 2013. Modelling the effect

of national culture on countries’ innovation

performances: A conditional full frontier approach. Int.

Rev. Appl. Econ. 27, 656–678.

Hall, E.T., 1976. Beyond Culture. Anchor, Garden City,

CA.

Hansen, S., Baroody, A.J., 2020. Electronic Health Records

and the Logics of Care: Complementarity and Conflict

in the U.S. Healthcare System. Inf. Syst. Res. 31, 57–

75. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2019.0875

Hofstede, G., 2011. Dimensionalizing Cultures: The

Hofstede Model in Context. Online Read. Psychol.

Cult. 2. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014

Hofstede, G.H., Hofstede, G.J., Minkov, M., 2010. Cultures

and organizations: software of the mind: intercultural

cooperation and its importance for survival, 3rd ed. ed.

McGraw-Hill, New York.

Hofstede Insights, 2020. Whitepaper: Organisational

Culture: What You Need to Know.

Hoque, Md.R., Bao, Y., 2015. Cultural Influence on

Adoption and Use of e-Health: Evidence in

Bangladesh. Telemed. E-Health 21, 845–851.

https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2014.0128

Kowatsch, T., Otto, L., Harperink, S., Cotti, A., Schlieter,

H., 2019. A design and evaluation framework for digital

health interventions. It - Inf. Technol. 61, 253–263.

https://doi.org/10.1515/itit-2019-0019

Leidner, D.E., Kayworth, T., 2006. A Review of Culture in

Information Systems Research: Toward a Theory of

Information Technology Culture Conflict. MIS Q. 30,

357–399.

Moonen, P., 2017. The impact of culture on the innovative

strength of nations: A comprehensive review of the

theories of Hofstede, Schwartz, Boisot and Cameron

and Quinn. J. Organ. Change Manag. 30, 1149–1183.

https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-08-2017-0311

Nwabueze, S.N., Meso, P.N., Mbarika, V.W., Kifle, M.,

Okoli, C., Chustz, M., 2009. The Effects of Culture of

Adoption of Telemedicine in Medically Underserved

Communities, in: 2009 42nd Hawaii International

Conference on System Sciences. Presented at the 2009

42nd Hawaii International Conference on System

Sciences, pp. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1109/

HICSS.2009.430

Prim, A.L., Filho, L.S., Zamur, G.A.C., Di Serio, L.C.,

2017. The relationship between national culture

dimensions and degree of innovation. Int. J. Innov.

Manag. 21, 1–22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/S1363919

61730001X

Smith, P., Trompenaars, F., Dugan, S., 1995. The Rotter

Locus of Control Scale in 43 Countries: A Test of

Cultural Relativity. Int. J. Psychol. 30, 377–400.

Srite, M., Karahanna, E., 2006. The Role of Espoused

National Cultural Values in Technology Acceptance.

MIS Q. 30, 679–704. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148745

Straub, D., Loch, K., Evaristo, R., Karahanna, E., Srite, M.,

2002. Toward a Theory-Based Measurement of

Culture. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. JGIM 10, 13–23.

https://doi.org/10.4018/jgim.2002010102

Thatcher, J.B., Srite, M., Stepina, L.P., Liu, Y., 2003.

Culture Overload and Personal Innovativeness with

Information Technology: Extending the Nomological

Net. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 44, 74–81.

Thiel, R., Deimel, L., Schmidtmann, D., Piesche, K.,

Hüsing, T., Rennoch, J., Stroetmann, V., Stroetmann,

K., 2019. SmartHealthSystems: international

comparison of digital strategies. Gütersl. Bertelsmann-

Stift.

Thornton, P.H., Ocasio, W., Lounsbury, M., 2012. The

institutional logics perspective: A new approach to

culture, structure, and process. Oxford University Press

on Demand.

Yaveroglu, I.S., Donthu, N., 2002. Cultural Influences on

the Diffusion of New Products. J. Int. Consum. Mark.

14, 49–63.

Yusif, S., Hafeez-Baig, A., Soar, J., 2017. e-Health

readiness assessment factors and measuring tools: A

systematic review. Int. J. Med. Inf. 107, 56–64.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.08.006

Be Aware! Indications for Intercultural Awareness for Digital Health Innovations and Innovation Capability

811