Optimal Decision of Exploding Offer based on Consumer Search

Model

Lei Wang

School of Economics Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China

Keywords: Exploding Offer, Free Recall, Consumer Search.

Abstract: Exploding offer becomes more and more popular business management strategy among firms. This paper

studies firm’s choices of price and strategy (whether to choose exploding offer) as well as the welfare

implications in duopoly competition based on consumer search model. Through backwards induction method,

we find that both firms choose free recall (an exploding offer) with a small (large) search cost; and with a

moderate search cost, one firm chooses free recall while the other chooses an exploding offer. Consumer

surplus reaches its maximum if the search cost is low (high) and therefore both firms choose an exploding

offer (free recall). In addition, this paper extends the basic model with two extensions, considering the

existence of consumer’s observational learning and limited comparability of price. Our conclusions may offer

practical suggestions about business management.

1 INTRODUCTION

Exploding offer is commonly observed in many

business cases. For example, in door-to-door selling,

a salesman often claims that he wouldn’t visit again

and customers will never get his products otherwise

they buy now; many e-commerce platforms, such as

Taobao and Jingdong in China and Gilt, Rue Lala,

HauteLook and Vinfolio in America, often conduct

the strategy of exploding offer about a variety of

goods, which is also called as flash sales. Although,

there are still many firms just conducting the strategy

of free recall only or in most instances, which allows

consumers to return to their products freely.

In this paper, we explore under what conditions a

firm prefers an exploding offer to free recall based on

a duopoly model with consumer search and

investigate the logic behind the choice of firms as

well as the welfare implications. In consideration of

worries about prices of exploding offer in people’s

mind due to their quick decisions, we discuss whether

products are cheaper indeed when offered without

another chance than when people are allowed to

reconsider products freely. Our analysis shows that in

equilibrium firms’ choice depends crucially on the

value of the search cost. Specifically, with a small

(large) search cost, both firms choose free recall (an

exploding offer); and with a moderate search cost,

one firm chooses free recall while the other chooses

an exploding offer. Moreover, the price is higher

when both firms choose an exploding offer than that

when both firms choose free recall; however, when

the two firms choose different strategies, the price of

a firm with an exploding offer is lower than that with

free recall. In addition, consumer surplus reaches its

maximum if the search cost is low (high) and

therefore both firms choose an exploding offer (free

recall).

The literature about exploding offer in consumer

search model is scarce. With respect to consumer

search, there are many works assuming products are

homogeneous or heterogeneous, analyzing firm’s

pricing strategy (Ellison, Wolitzky, 2012),

advertising management (Moraga-Gonzalez, 2011),

and so on. While they don’t consider firm’s strategies

of exploding offer and free recall. Durmus et al.

(Durmus, et al, 2015) shows that exploding offer can

promote sales of luxury goods, however they don’t

analyze consumer’s search behaviors and firm’s

strategic choice of exploding offer. In contrast, our

model studies under what conditions a firm prefers an

exploding offer to free recall in consideration of

consumer’s search and compare prices under

different strategies.

Wang, L.

Optimal Decision of Exploding Offer based on Consumer Search Model.

DOI: 10.5220/0011160600003440

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Big Data Economy and Digital Management (BDEDM 2022), pages 87-91

ISBN: 978-989-758-593-7

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

87

2 MODEL AND METHODS

The introductions of model are as follows:

Firms. There are two firms, firm 1 and firm 2,

producing horizontally differentiated goods at zero

marginal cost which are labelled as product 1 and

product 2 respectively. The two firms need to choose

one of two strategies from exploding offer and free

recall, as well as pricing their product with

i

p

,

1, 2i =

. If the firm chooses exploding offer,

consumers can buy the product only in their first

search of this firm and have no chance to return. If the

firm chooses free recall, consumers can buy the

product whenever they want.

Consumers. Consumers search products

sequentially and know their valuation

i

u

,

1, 2i =

about products in the search process.

i

u

is an i.i.d

draw from the distribution function

()

F

u on the

support

max

[0, ]u

, and its density function is

()

f

u .

The probability of consumers search firm 1 or firm 2

first is equally. When consumers reach a firm claiming

exploding offer, they can buy this product at once, or

continue to search another product without no chance

to return the first firm. When consumers reach a firm

claiming free recall, they can buy this product at once,

or continue to search another product with the chance

to return the first firm freely. Without loss of

generality, we assume that the cost of the first search

is zero and the cost of the second search is

s

.

The timing of the game is as follows. In the first

stage, two firms choose exploding offer or free recall

simultaneously and compete in prices. In the second

stage, consumers begin to search and decide whether

to buy and when to buy.

According to Armstrong and Zhou (2016), we

define that

max

() [max{0, }] ()

i

u

iu ii i

p

Vp E u p Qudu≡−=

()

i

Vp

is the consumers’ utility when consumers

reach the product

i

, which is a decreasing function

of

i

p

. If

()Va s=

, ()Va is the utility of the

product

i

when consumers are indifferent to

whether to continue searching or not.

When two firms choose the same strategy, the

outcome is given as Armstrong and Zhou (2016).

Specifically speaking, given the uniform distribution

of

()

F

u , when two firms claim free recall together,

the equilibrium price

f

p

satisfies

2

1(1)

ff

pap−=+ , and when two firms claim

exploding offer together, the equilibrium price

ex

p

satisfies the following equation:

2

(2 2 ) 1

ex ex

psp−+ =

.

Due to our analysis allowing for free choice for

firms instead of prior strategy, we explore the

asymmetry situation. When firm 1 chooses free recall

and firm 2 chooses exploding offer, the equilibrium

price

1d

p

and

2d

p

is decided by

2

212

12122

1(1)(2)

(1 )(1 3 ) 2 0

ddd

ddddd

papp

ppppps

−=+ −

+−+ +=

.

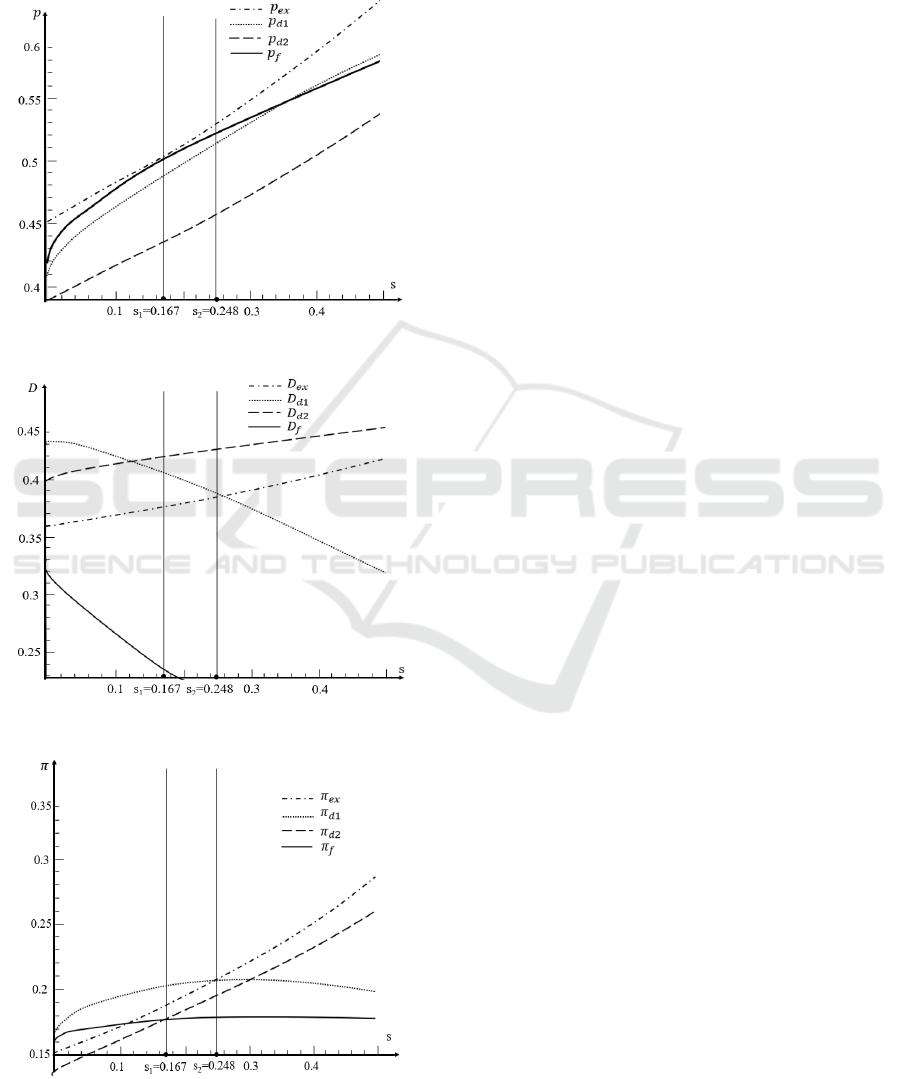

As depicted in Figure 1,

f

p

,

ex

p

,

1d

p

and

2d

p

are represented separately by thick dash line,

dot dash line, fine dash line and full line.

Proposition 1. Compared to the price under free

recall, the price under exploding offer is not cheaper

all the time:

(a) The price when both firms choose exploding

offer is higher than that when both firms choose free

recall.

(b) In the asymmetric situation, the price under

exploding offer is lower than that under free recall.

To understand the first point, we need to analyze

the difference of consumers between free recall and

exploding offer. When claiming exploding offer, firm

i

owns two groups of consumers: (i) who buy

product

i

at once when reaching product

i

at the

first time, (ii) who continue to search and buy product

i

after searching product

j

first. However, when

claiming free recall, firm

i

owns three groups of

consumers. Besides the two groups of consumers

aforementioned, the third group is consumers who

return to buy product

i

after searching product

i

and product

j

. Compared to the situation where

both firms choose exploding offer, each firm has

incentives to reduce price to attract the third group of

consumers when both firms choose free recall so that

the equilibrium price is lower. This point identifies

with Armstrong and Zhou (Armstrong, Zhou, 2016).

Nevertheless, Armstrong and Zhou (Armstrong,

Zhou, 2016) assume two firms choose the same

strategy ex-ante and explore whether a firm has

incentives to deviate from the symmetry. In contrast,

we allow for free choice for firms instead of prior

strategy, discussing how firms choose strategies

according to consumer search. As a consequence, we

get the second point in the proposition 1.

The intuition of the second point is as follows. In

the situation where firm

i

chooses exploding offer

and firm

j

chooses free recall, firm

i

always has

incentives to conduct price-off promotions because

its consumers would never return back once they

BDEDM 2022 - The International Conference on Big Data Economy and Digital Management

88

decide to continue searching. Theoretically, firm

j

can also price lower than firm

i

.If firm

j

prices

products in this way, it will face more demand but too

lower price, which reduces its revenue and can’t lead

to an equilibrium outcome.

Figure 1: Price in different situation.

Figure 2: Demand in different situation.

Figure 3: Profit in different situation.

Proposition 2. For horizontally differentiated

firms, their choice of free recall or exploding offer

relies crucially on the value of search cost. Concretely

speaking,

(a) When

1

[0, ]

s

s∈

, both firms choose free

recall;

(b) When

12

[, ]

s

ss∈

, one firm chooses free

recall and another one chooses exploding offer;

(c) When

2max

[, ]sss∈

, both firms choose

exploding offer.

To understand the first point in the proposition 2,

we need to explain why firm

i

’s best response is

always free recall no matter what firm

j

chooses

when

1

[0, ]

s

s∈

. When the search cost is very low,

consumers incline to search more. If firm

j

claims

free recall, firm

i

’s exploding offer will refuse these

consumers who reach firm

i

first but continue

searching, which is called the strategic effect of

exploding offer. In order to attract more consumer to

buy at once after their first search of product

i

, firm

i

must reduce its price so as to increase its demand.

However, the promotion of demand can’t compensate

the loss caused by low price, which leads firm

i

not

to choose exploding offer. If firm

j

claims

exploding offer, the demand of firm

i

under

exploding offer will be low because its high price (as

depicted in figure 1) as well as the strategic effect of

exploding offer aforementioned. The loss caused by

low demand overweighs the promotion due to high

price, which leads firm

i

not to choose exploding

offer. In a word, firm

i

’s best response is always

free recall no matter what firm

j

chooses when

1

[0, ]

s

s∈

.

When

12

[, ]

s

ss∈

which is moderate, the

consumers’ motivation of searching is not

too intense,

which means that the strategic effect of exploding

offer won’t be too obvious. If firm

j

claims free

recall, the price of firm

i

under exploding offer is

lower compared to free recall, which will attract more

consumers who buy at once as well as who continue

searching firm

i

after visiting firm

j

. The

promotion caused by high demand compensates the

loss due to the strategic effect of exploding offer. If

firm

j

claims exploding offer, the price of firm

i

under free recall is lower compared to

exploding offer,

which increases demand from the three groups of

consumers aforementioned. The promotion of

demand can’t compensate the loss caused by low

price. In a word, when

12

[, ]

s

ss∈ , one firm chooses

Optimal Decision of Exploding Offer based on Consumer Search Model

89

free recall and another one chooses exploding offer.

When

2max

[, ]sss∈

, firm

i

’s best response is

always exploding offer no matter what firm

j

chooses. If firm

j

claims free recall, the price of

firm

i

under exploding offer is lower compared to

free recall, which will attract more consumers who

buy at once as well as who continue searching firm

i

after visiting firm

j

. The promotion caused by

high demand compensates the loss due to the strategic

effect of exploding offer. If firm

j

claims

exploding offer, the demand of firm

i

under

exploding offer doesn’t decrease much because the

high search cost deters consumers to continue to

search. Considering the higher price under exploding

offer compared to free recall, the promotion caused

by high price compensates the loss of demand. As a

result, firm

i

’s best response is always exploding

offer no matter what firm

j

chooses.

Proposition 3. When search cost is low, the

condition where both firms choose exploding offer is

best for consumers; when search cost is high, the

condition where both firms choose free recall is best

for consumers.

The intuition of proposition 3 is as follows. When

search cost is low, consumers feel more incentives to

continue to search after the first visit. However, when

both firms choose exploding offer, consumers will

search less which avoids the decrease of consumer

surplus. Although the price under both firms’

exploding offer is high, the decrease of consumer

surplus caused by high price is overweighed by the

positive effect due to the search deterrence effect of

exploding offer. When search cost is high, consumers

will search little, which avoids the decrease of

consumer surplus. What’s more, the price

competition is intense when both firms choose free

recall together, which reduces the payment of

consumers. The positive effect of low price

compensates the weakly negative effect of consumer

search.

3 TWO EXTENSIONS OF MODEL

3.1 The Existence of Observational

Learning

In general, consumers’ decisions are not always

independent. For example, a consumer who plans to

buy a new laptop, may begin his search with Dell if

he observes his friend’s purchase of a Dell laptop. In

consideration of consumer’s observational learning,

how a firm and its competitor choose from free recall

and exploding offer and how they price

their products?

Observational learning has received much attention

in the study of firm’s pricing strategy (Galeotti, 2010,

Campbell, 2013, Kovac, Schmidt, 2014), while there

are few studies investigating firm’s choice from

exploding offer and free recall under observational

learning. In this part, we explore under what

conditions a firm prefers an exploding offer to free

recall based on a duopoly model with consumer

search allowing for consumers’ observational

learning.

Firms. There are still two firms, firm 1 and firm

2, producing horizontally differentiated goods at zero

marginal cost which are labelled as product 1 and

product 2 respectively. The two firms need to choose

one of two strategies from exploding offer and free

recall, as well as pricing their product with

i

p

,

1, 2i =

. with the goal of maximize their discount

revenue with discount factor

δ

( [0,1)

δ

∈ ).

According to Daniel and Sandro (2018), nature

chooses a state

Ω from three possible states

012

{,, }Ω= Ω Ω Ω

.The state

0

Ω=Ω

is realized

with probability

1

ρ

−

, in which the utility of

product 1 and product 2 both draws from

()

Gu(with

associated density

()

g

u

) on the support

[, ]uu

. The

state

1

Ω=Ω

(

2

Ω=Ω

)is realized with probability

2

ρ

, in which the utility of product 1 (product 2) draws

from

()

Gu on the support

[, ]uu

, while the utility

of product 2 (product 1) is

()

bb

uu u<

. That is to say,

there are two states where one of the two products is

worse than another.

Consumers. Consumer

( 1, 2,3...)ii= arrives at

the market sequentially, making his purchasing

decision and leaving the market after observing his

predecessor. Consumer

( 1, 2,3...)ii= can only

observe the predecessor’s final decision without

knowing his process of search and payment.

Meanwhile, Consumer

( 1, 2,3...)ii= can’t know

whether firms claim exploding offer or free recall

unless he begins his search. The probability of the

initial consumer search firm 1 (firm 2) first is

1

2

,

while the probability of the rest consumers search

firm 1 (firm 2) first is related with what they observe.

Proposition 4. Considering the existence of

consumer’s observational learning,

(i) compared to the price under free recall, the

BDEDM 2022 - The International Conference on Big Data Economy and Digital Management

90

price under exploding offer is not cheaper all the time,

which is similar to proposition 1.

(ii) both firms choose free recall when the search

cost is low; duopoly firms choose asymmetric

strategies when the search cost is high.

The intuition of part (i) of proposition 4 is similar

to proposition 1. As for part (ii), we show that both

firms won’t choose exploding offer together when the

search cost is high, which is different from the

conclusion of proposition 1. If firms both choose

exploding offer, they will cut down the price to

increase their demand of prior consumers so that

following consumers will increase because of less

search after observational learning, while the loss

caused by low price can’t be compensated by the

promotion due to increasing demand.

3.2 The Existence of Limited

Comparability

It’s common that consumers often face limited

comparability of price in their search process, and a

number of papers study the relationship between this

phenomenon with firm’s competition using different

models (Dow, 1991, Chen, et al, 2010, Piccione,

Spiegler, 2012, Kutlu, 2015). However, our

contribution is to explore under what conditions a

firm prefers an exploding offer to free recall based on

a duopoly model with consumer search in

consideration of the existence of consumer’s limited

comparability of price, which current works haven’t

discussed about.

In this part, when both firms claim free recall,

customers can return to firms freely to compare prices

accurately; when both firms claim exploding offer,

customers will be confused when they search the

second product and forget the first product’s price

due to no chance of return, and they will purchase at

random; when duopoly firms choose asymmetric

strategies, customers also face limited comparability

of prices. There are two conditions that consumers

will choose to continue searching: (i) when the utility

of the first product they search is lower than its price,

customers will be unsatisfied with the first product;

(ii) when the utility of the first product they search is

higher than the payment of price and search cost,

customers will be prone to search another product.

Proposition 5. Considering the existence of

consumer’s limited comparability, duopoly firms

choose asymmetric strategies when the search cost is

low; both firms choose free recall when the search

cost is high.

In this extension, duopoly firms won’t choose

exploding offer together. Because if consumers aren’t

satisfied with the second product they search, they

can’t return to the first firm so that they will leave the

market without purchase, which decreases the total

demand of the markets. The loss caused by demand

surpasses the gain caused by price, which explains

why duopoly firms won’t choose exploding offer

together.

4 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we explore under what conditions a firm

prefers an exploding offer to free recall based on a

duopoly model with consumer search. Our analysis

shows that in equilibrium firms’ choice depends

crucially on the value of the search cost.

Specifically, with a small (large) search cost, both

firms choose free recall (an exploding offer); and

with a moderate search cost, one firm chooses free

recall while the other chooses an exploding offer.

Moreover, the price is higher when both firms choose

an exploding offer than that when both firms choose

free recall; however, when the two firms choose

different strategies, the price of a firm with an

exploding offer is lower than that with free recall. In

addition, consumer surplus reaches its maximum if

the search cost is low (high) and therefore both firms

choose an exploding offer (free recall).

REFERENCES

Armstrong, M., Zhou, J. (2016). Search deterrence. Review

of Economic Studies. 83(1), 26-57.

Campbell, A. (2013). Word-of-mouth communication and

percolation in social networks. American Economic

Review. 103, 2466–2498.

Daniel, G., Sandro, S. (2018). Consumer search with

observational learning. RAND Journal of Economics.

49(1), 224-253.

Durmus, B., Erdem, Y. C., Ozcam, D. S., Akgun, S. (2015).

Exploring antecedents of private shopping intention:

the case of the turkish apparel industry. European

Journal of Business and Management. 7(12), 64–77.

Ellison, G., Wolitzky, A. (2012). A search cost model of

obfuscation. Rand Journal of Economics. 43(3), 417-

441.

Galeotti, A. (2010). Talking, searching, and pricing.

International Economic Review. 51, 1159–1174.

Kovac, E., Schmidt, R.C. (2014). Market share dynamics in

a duopoly model with word-of-mouth communication.

Games and Economic Behavior. 83, 178–206.

Morraga-Gonzalez, J.L., Petrikaite, V. (2013). Search

costs, demand-side economies, and the incentives to

merge under bertrand competition. The RAND Journal

of Economics. 44(3), 391-424.

Optimal Decision of Exploding Offer based on Consumer Search Model

91