Diaspora Diplomacy: Contemporary Problems of Countries in the

Sustainable Development Context

Natalia Sheludiakova

1a

, Iveta Mietule

2b

, Bakhorid Mamurov

3c

, Roza Karajanova

4d

and Volodymyr Kulishov

1e

1

State University of Economics and Technology, 16 Medychna Street, Kryvyi Rih 50000, Ukraine

2

Rezekne Academy of Technologies, 115 Atbrivosanas aleja, Rezekne, LV-4601, Latvia

3

Bukhara State University, 11 M. Iqbol Street,Bukhara 200114, Uzbekistan

4

Karakalpak State University named after Berdakh, 1 Ch. Abdirov Street, Nukus, 230100, Uzbekistan

Keywords: Globalization, Diaspora Policy, Diplomacy, Home Country, Host Country, Public Diplomacy, Socio-

Economic Impact, Institutionalization.

Abstract: In the globalization-driven world, the conceptual foundations of the entire system of international relations

are undergoing considerable changes. The defining shifts concern the expansion of the range of international

actors and the enrichment of the tools and functions of the diplomatic service. Diaspora is one of the emerging

non-state actors that can potentially make impact at the international level, although most states continue to

view it only as a means of achieving their national interests. As a result, the notion of “diaspora diplomacy”

has emerged, emphasizing the importance of diaspora as a transnational, liminal actor capable of influencing

both host and home countries as well as exert influence on international relations. States tend to make efforts

to institutionalize relations with their diasporas, which indicates the strategic importance that states attach to

it. Latvia, Ukraine and Uzbekistan are working to institutionalize diaspora diplomacy. While Latvia has come

significantly closer to this ultimate goal by building an extensive infrastructure for relations with diaspora,

diaspora policy in Ukraine is not yet a priority, though there is a willingness to cooperate on part of the

diaspora. Uzbekistan has set the diaspora issue on the agenda, but it still lacks strategy as well as effective

mechanisms for its implementation.

1 INTRODUCTION

The forces of globalization have led to the decline of

traditional realistic visions of international relations

and the significant reshaping of the world politics.

The development of complex interdependence and

transformation of the world into a large network,

where people, goods, capital and information move

freely, resulted in the diffusion of world power and

the diminished role of the state. Instead, the outlines

of new political actors are looming in the

international arena. International governmental

organizations as supranational institutions, non-

governmental organizations as representatives of the

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6721-8077

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7662-9866

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2598-8441

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0439-1913

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8527-9746

world civil society, private sector, non-state

communities enter the international relations domain

on their own rights and form new modes of global

networking and transnational partnerships. The new

configuration of the international system provides all

its representatives to be included in the global

development strategy and work together to

implement it. An inclusive partnership with shared

responsibility for the current and future development

of the world, provides an opportunity to take a more

comprehensive approach to achieving sustainable

development goals. It is not only states and

international organizations that are stakeholders in

solving the problem of development, but also various

Sheludiakova, N., Mietule, I., Mamurov, B., Karajanova, R. and Kulishov, V.

Diaspora Diplomacy: Contemporary Problems of Countries in the Sustainable Development Context.

DOI: 10.5220/0011346400003350

In Proceedings of the 5th International Scientific Congress Society of Ambient Intelligence (ISC SAI 2022) - Sustainable Development and Global Climate Change, pages 167-176

ISBN: 978-989-758-600-2

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

167

non-state actors, representatives of civil society and

so on.

Political advances and transformation of

international environment resulted in forging new

types of diplomacy in response of the need to rethink

itself in new contexts. The old definition of

diplomacy emphasizing formal communication and

clear delineation of responsibilities is becoming

increasingly irrelevant. The complex environment

and multiple objectives diplomacy is expected to

achieve, prescribe it to become more flexible,

resilient and multifaceted.

The emergence of diaspora diplomacy is

considered to be a significant part of this kind of

transformations. By employing tools of public

diplomacy as well as ‘new’ inclusive diplomacy it

provides broad opportunities to address the problems

essential for both states and international community.

Diaspora diplomacy is becoming more prominent in

states’ foreign policies and the establishment of

global infrastructure of diaspora engagement.

2 DIASPORA DIPLOMACY AS A

SOFT POWER INSTRUMENT

2.1 Globalization Trends and Public

Diplomacy Context

The traditional mode of diplomacy is now

complemented by a range of new forms and offshoots

that significantly extend its capacities and

possibilities to exert influence under contemporary

conditions (Melissen & Wang, 2019). One of the

advanced forms of diplomatic practices is public

diplomacy that focuses not so much on

intergovernmental relations as on government-to-

people communication; conveys important messages

not to decision-makers but to an audience capable of

influencing them. Public diplomacy is often seen as

the one preoccupied to “win the war on hearts and

minds” (Dolea, 2015).

Since the introduction of “soft power” concept by

Joseph Nye, public diplomacy gained much attention

as a tool of reputation management, building

relationships through dialogue and networking

activities. For a long time, it was viewed solely in the

context of statecraft, but an array of actors and

stakeholders has been recently included into its scope.

Public diplomacy, as Melissen (2013) puts it, is “a

metaphor for a democratization of diplomacy, with

multiple actors playing a role in what was once an

area restricted to a few”.

The public, which throughout history has often

fallen out of the spotlight of diplomatic practice,

today acquires the role of an active agent, which

determines the necessity to redefine public

diplomacy. According to Hocking, there are several

aspects that contribute to this redefinition. 1)

Democratic responsibility as a determining feature of

the new international environment. Previously

diplomats were only aware of the potential impact of

public opinion, but today they recognize the need for

direct public involvement in diplomacy. 2)

Globalization-driven changes in people’s perceptions

of local and global environments. They are connected

with overgrowth of social networks transcending the

geographical and political boundaries, intensification

of these processes in conditions of compressed time

and space. 3) Transformational impact of

technological and communication innovations on

foreign affairs and diplomacy. 4) Impact of media

which evolved from the tool of government’s public

diplomacy to an agent that sets agenda, puts pressure

on policy-makers, regulates the flows of information

to public etc. 5) The growing importance of image

and national branding in international politics. Unlike

previous periods, the country’s modern image and

branding are seen not as elite’s preoccupation, but

rather as a public good (Hocking, 2005).

Public diplomacy is sometimes viewed as an

immediate tool of foreign policy, and the close

relation between the two is obvious: public diplomacy

cannot be developed regardless of a country’s foreign

policy. On the other hand, instead of influencing

specific policies and decision-making processes in a

foreign country, public diplomacy is concerned with

forming attitudes, influencing perceptions, and

building trust. Therefore, its results are not

immediate, but rather become visible over long

distances (Sheludiakova et al., 2021).

By bonding communication and international

relations frameworks, public diplomacy enables

countries and international community to promote

essential values, especially within Sustainable

development goals strategy. There is a vast array of

SDGs initiatives that employ public diplomacy

toolkit to create awareness and “plug” the

governments and societies into sustainable

development contexts. At the same time, public

diplomacy relies on SDGs as narratives capable of

uniting countries and promoting cooperation. So,

public diplomacy penetrates the SDG strategy by

being both a goal and a means of SDGs (Jimenez,

2019).

Another innovation and the rise of the “new

diplomacy” is connected with the pluralization of

ISC SAI 2022 - V International Scientific Congress SOCIETY OF AMBIENT INTELLIGENCE

168

actors in world politics, including supranational

actors, NGOs, MNCs, indigenous communities etc.

This range of studies goes beyond state-centric

notions of diplomacy as the prerogative of the state.

They assign the diplomatic agency to a number of

non-state entities capable of promoting dialogue and

interaction between states, societies and groups

(Cornago, 2013). Thus, the hierarchy in diplomatic

relations is being flattened, and non-state entities

enter into diplomatic relations without the need for

mutual recognition by other actors.

Multiplication of diplomatic actors also leads to

the fact that the list of areas considered to be

“diplomatic” is expanding. Accordingly, there is a

transition from diplomacy as an institution to

diplomacy as a practice. And this transition is closely

intertwined with the process of formation of means,

techniques and ways of conducting public diplomacy.

2.2 Diaspora as an Emerging Non-state

Actor

Among non-state actors, diaspora occupies a special

place, and its prominence in international relations is

becoming increasingly salient. Diaspora as a political

phenomenon has gained considerable attention from

scholars who have studied its features as social

formation, boundaries, conditions and motives of

engagement, as well as the ways of diaspora

involvement in political and cultural influences both

on host country and country of origin.

According to the International Organization for

Migration, diaspora includes “members of ethnic and

national communities who have left, but maintain

links with, their homelands” (Ionescu, 2006). In

general, when defining diaspora, the traditional

approach implies the need to include several aspects

in its conceptualization: geographical distance from

the country of origin; internal group solidarity;

identification with the country of origin; acting as

transnational population, etc. However, several

adjustments should be made to this traditional set of

defining features of diaspora, which expand this

concept and at the same time concretize it.

First of all, the category of diaspora includes

representatives both of states and of non-state

communities in the host country, such as ethnic or

religious groups.

The issue of identification is also not as simple as

it seems at first glance. In general, different groups

attribute different meanings to this concept. In

particular, for diaspora, who think of themselves as

part of a nation but outside the state, identity is more

valuable than for people inside the country who

experience it in their daily lives. This is why diaspora

takes an active part in activities that support and

sustain national identity, as they nourish their self-

image (Shain & Barth, 2003). However, members of

diaspora do not necessarily identify with their country

of origin, but may be identified as such by others. In

addition, the identification of diaspora members is

usually twofold: they identify themselves both with

their country of origin and their country of residence.

Culturally and historically, Docker defined this

double identification as “a sense of belonging to more

than one history, to more than one time and place, to

more than one past and future” (Docker, 2001) At the

same time, members of diaspora are also

characterized by the idea of themselves as a separate

group with a common background, experience and

sense of connection that distinguishes them from

other groups within the host county and from

compatriots in the country of their origin.

An important aspect in defining diaspora is the

process of its formation: diaspora members or their

ancestors have been dispersed from an original

“nucleus”, and according to some researchers, this

process is often associated with forced emigration.

Taking this factor into account helps to draw a line

between the diaspora itself and indigenous ethnic

enclaves that may be formed outside the homeland

due to changing borders. Involuntary resettlement is

a condition that has a special impact on relations with

the country of origin, fundamentally different

attitudes and spiritual connection with it.

Therefore, there are many variables that

complicate the precise and unambiguous definition of

diaspora. This allows Brubaker (2005) to say that

diaspora is not a homogeneous, close-knit group of

people, but rather a “category of practice, project,

claim and stance”, thus giving this notion of

multidimensionality.

Diaspora represents the connectivity and mobility

of the globalized world. As a community that is

geographically separated from the country of origin,

diaspora in many cases appears as an extension of its

capacities. As a result, states are changing the way

they think about diaspora and try to build mutually

beneficial relations with it. Instead of considering

members of diaspora as “lost” to the state,

governments tend to create networks, mobilize

groups or individuals, and engage them in

cooperation, viewing them as a powerful tool of soft

power. However, by endowing diaspora with a certain

subjectivity and trying to persuade it to defend

nation’s interests, states also undertake to develop

mechanisms to protect the rights of diaspora in the

host’s environment (Bravo, 2015).

Diaspora Diplomacy: Contemporary Problems of Countries in the Sustainable Development Context

169

Diaspora serves as an additional opportunity to

achieve diplomatic goals, but at the same time

challenges traditional diplomatic theory and practice.

Living outside the country of origin, diaspora still

claims legitimate stake in it, thus undermining the

established understanding of the state, its nature and

borders, as well as such traditional political

institutions as loyalty and citizenship.

One could even say that, in a global context,

diaspora can also be seen as part of a populace living

outside the state. Despite its geographical

detachment, it can act as one of the internal groups,

because it resides “within the people”. This leads to

the de facto recognition of the role of diaspora as the

internal interest group in both the home country and

the host country, and thus to the conceptualization of

diaspora as a transnational actor capable of

influencing politics in both countries. This influence

is implemented by various means, and directly affects

the domestic policies and processes in the respective

countries, but each of the processes has a foreign

policy context. This gives grounds for some

researchers to position diaspora as neither fully

domestic nor fully foreign actors, which calls into

question the distinction between domestic and foreign

policy as separate areas.

Diaspora activities within the host country always

aim to influence government decisions and foreign

policy in general towards the home country. The main

means of achieving this goal is the ethnic lobby,

whose role in liberal democracies is twofold: on the

one hand, it is a manifestation of pluralism and forces

that balance traditional political elites in shaping

national interests; and on the other are designed to

promote national interests of home country leading to

decisions that may jeopardize national security and be

out of tune of the national interests of the host country

itself. Weight in the host country is often the main

prerequisite for diaspora’s ability to influence the

home country and a determinant of its diplomatic

value. Moreover, the range of tools for realizing this

influence is extremely wide - from direct investment

in the economy to acquiring the role of cultural

ambassadors and image-makers of the homeland.

The growing interest of diaspora communities in

the domestic policy of home country is associated

with innovations that promote this involvement, in

particular, the development of technology and related

opportunities for bilateral communication,

empowerment of diaspora through providing outside

nationals dual citizenship and electoral rights, and in

general providing diaspora members with formal

ways to influence the politics of the country of origin.

According to Koslowsky (2005), these developments

indicate the so-called “globalization of domestic

policy”.

The contribution of diaspora to the development

of the home country can be tangible and intangible.

Tangible contributions include economic remittances

and homeland investments motivated both by

economic gains and patriotic feelings. Diaspora can

also come up with intangible contributions, namely,

professional expertise and skill transfers, political

influence, international networking, diplomatic

functions of communication and mediation as well as

cultural ambassadorship and nation-branding

(Ionescu, 2006).

Diaspora has the potential to act as a mediator in

times of political crises and conflicts between

domestic political forces within the home country.

Diaspora representatives appear to be the promoters

of peace-building initiatives and negotiations,

highlight the human rights situation in the home

country during the crisis and directly lobby certain

issues in the host country government and

international organizations. Fitting mediator role to

diaspora is due to the fact that, being at a considerable

distance from the epicenter of the conflict, it is able

to be outside the conflict and give an objective

assessment to it, but still remain an interested

stakeholder.

The borderline position of diaspora, which

belongs to two countries and two cultures at the same

time, stipulates another diplomatic function, namely

mediation referred to as the ability of diaspora to act

as an intermediary in interstate relations. In addition

to ethnic lobby, diaspora can facilitate bilateral

relations between host and home countries, transfer

values, function as a bridge between societies and

form cross-community relationships that go beyond

the official, i.e. perform a number of public

diplomacy functions.

It would be improperly to overlook the prominent

role of diaspora in a relatively new, but no less

important, strategy for positioning the state in the

international arena – nation-branding. Creating and

maintaining an image in today’s networked

international environment determines how a country

is perceived by the rest of the world, what values and

qualities are attributed to it, and how these

connotations resonate with the citizens’ vision of the

country and nurture their patriotic feelings. In this

context, diaspora is a kind of “brand ambassador”.

They are able to act as a trustworthy source and

present the country’s brand on an interpersonal level,

promote home country goods and generate publicity

for its cultural products (Aikins & White, 2011).

ISC SAI 2022 - V International Scientific Congress SOCIETY OF AMBIENT INTELLIGENCE

170

Given the specific status of diaspora, its

involvement in what is recognized as “foreign

affairs”, its ability to independently exercise agency

in this area, we can conclude that diaspora can be

considered as an independent actor. Acquiring the

role of a diplomatic actor and an independent entity

in the field of international politics implies freedom

in its activities and motives: diaspora does not

necessarily defend the interests of the state, but also

offers alternative projects, pursues its aspirations,

promotes its own position and more. The change in

the status of diaspora from a vehicle of diplomacy to

the role of a new diplomatic actor and stakeholder in

the implementation of foreign policy is reflected in

the formation of the concept of “diaspora diplomacy”.

Although the relationship between diplomacy and

diaspora has been thoroughly studied from different

angles, the very concept of diaspora diplomacy

remains rather crude. This is due to the relative

novelty of this concept in academic field as well as

international politics, where realistic views continue

to dominate. Equally important is the fact that

diaspora diplomacy, like any other type of diplomacy,

does not have a universal formula, and is determined

by the peculiarities of the country’s history, its

economic condition, social processes and so on.

These factors along with the level of communication

and interaction with diaspora can be crucial for

diaspora’s decision to take a passive or active role in

foreign and domestic policies, to act as a constructive

or destructive actor.

Reducing diaspora diplomacy purely to relations

with host and home countries significantly narrows

the perception of diaspora communities and their

subjectivity in globalized world politics. According to

Ho and McConnell (2019), the key actors of diaspora

diplomacy include state actors that engage with

diasporas, non-state and international actors who are

targets of its diplomatic activities and with whom

diaspora enters into mutually beneficial relations.

Thus, diaspora diplomacy is defined as “diaspora

assemblages composed of states, non-state and other

international actors that function as constituent

components of assemblages, connected through

networks and flows of people, information and

resources”.

At the same time, the attention of states to

diaspora, government initiatives to incorporate

relations with foreign compatriot communities into

their foreign policy strategy and efforts to

institutionalize these relations is one of the indicators

that diasporas are gaining diplomatic status on their

own rights.

3 INSTITUTIONALIZATIONS OF

DIASPORA RELATIONS IN

LATVIA, UKRAINE AND

UZBEKISTAN

3.1 Latvia Scores in Diaspora

Diplomacy

States are becoming increasingly aware of the

strategic importance of diaspora as a transnational

agent of change, and this is the reason for the surge in

the activity of states to institutionalize relations with

their diasporas. Starting from the last decade of the

20th century, governments began to establish

ministries and offices to engage diasporas, to

establish mutually beneficial relationships with their

compatriots abroad, based on the networking

capabilities of their embassies and consulates. Israel,

Ireland, Armenia, Australia, etc. are classic examples

of countries that have long focused on diaspora

policy, but we can add to this list a large list of

countries from around the world that are promoting

changes in the diplomatic sector on diaspora policy.

By creating special bodies and agencies for diaspora

affairs governments formalize their relations, and it is

considered to be a step towards the establishment of

effective institutions and relevant infrastructure. The

institutionalization is set to carry on the relations

between the country and its diaspora on common

normative standards and value patterns. It involves

the establishment of institutions in order to coordinate

the relations, and their acceptance as empirical

regularities rather than formal rules. The

institutionalization efforts are one of indicators of the

considerable change in the way countries view

diaspora. The latter appears to be an ally rather than

an instrument; and diaspora relations tend to shift

from situational and problem-solving to long-term

fundamental and of strategic value.

Latvia is one of the countries that actively

implements diaspora strategies and policies.

Intensification of efforts to establish cooperation with

diaspora was set on in the mid-2000s, when EU

accession and the opening of the labor market led to

significant outmigration of the Latvian population.

Economic migrants have become quantitatively

predominant only in the last twenty years, but they

have not been the only source of diaspora formation

in which a significant role is played by the “old”

diaspora, which left its homeland during previous

waves of emigration, particularly during the world

wars. The main points of concentration of Latvian

emigrants are the United Kingdom, the United States,

Diaspora Diplomacy: Contemporary Problems of Countries in the Sustainable Development Context

171

Germany, Sweden and others. The percentage of

emigrants in relation to the total population of Latvia

is quite high - 17.8%, which is 332,220 people, while

the level of impact on the Latvian economy remains

insignificant. Thus, remittances in Latvia’s GPD are

3.3% (according to EUGDF).

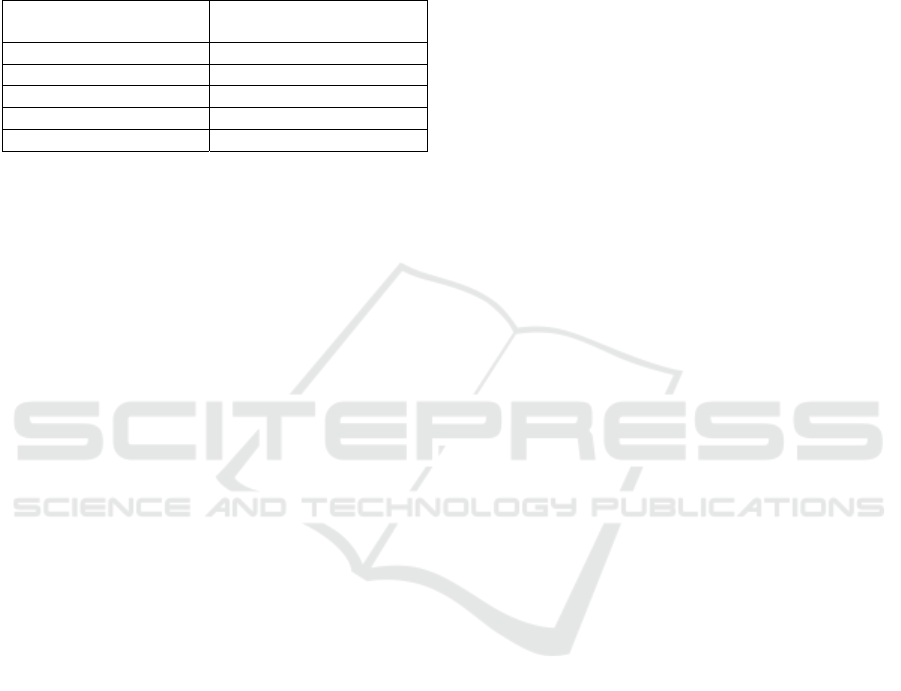

Table 1: Top countries of the Latvian diaspora destination.

Host country Number of Latvian

nationals abroa

d

Russia 89,368

United Kin

g

do

m

46,248

German

y

32,305

USA 27,172

Irelan

d

24,291

The growth of Latvian nationals living outside Latvia

in the early 21st century has been the starting point for the

Latvian government’s initiatives to manage relations with

diaspora. Today the country has unfolded a well-organized

infrastructure for diaspora relations. The main authority for

the implementation of policy in this direction is vested in

the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Latvia

and its subordinate system of diplomatic and consular

missions. Previously the main documents of strategic

importance that coordinated the activities of the Latvian

Foreign Office were The Guidelines on National Identity,

Civil Society and Integration Policy for 2012-2018 and

National Identity, Civil Society and Integration Policy

Implementation Plan for 2019-2020. Today the overarching

framework of diaspora policy in Latvia is established by the

Diaspora Law (2019). It regulates key issues of cooperation

with diaspora communities, establishes its basic principles

and objectives, and provides for the existence of certain

mechanisms for their implementation.

The adoption of the law was preceded by a series of

discussions and consultations between the government and

representatives of those directly affected by the

forthcoming legislation. The diaspora representatives

advocated a fairly broad interpretation of the concept of

“diaspora”, which would include different categories of

people who identify themselves as related to Latvia. It is

this broad approach that has formed the basis for defining

diaspora contained in the law as ‘permanently residing

outside Latvia citizens of Latvia, Latvians and others who

have a connection to Latvia, as well as their family

members’. We agree with Birka and Kļaviņš (2019), who

consider this “victory” of the diaspora to be a manifestation

of the power of diaspora diplomacy.

According to the Diaspora Law, diaspora policy in

Latvia is to be carried out on a systematic basis and have

stable funding from the state budget. Preservation of

Latvian language and culture, return migration

encouraging, support of civic and political participation of

the diaspora are key engagement policies for Latvians

living abroad.

In the context of Latvia’s diaspora policy, it should also

be mentioned that the law allows the acquisition of dual

citizenship in the country for persons residing in the EU,

NATO and countries with which Latvia has concluded

relevant agreements. The issue of dual citizenship is an

important component of ensuring the participation of the

diaspora in the political life of the country by providing its

representatives with the possibility of direct electoral

influence.

In order to coordinate diaspora policy, involve

members and organizations of the diaspora in the processes

of setting priorities and evaluating the effectiveness of this

policy, the Diaspora Advisory Council has been established

in Latvia. It consists of representatives delegated by public

administration authorities, local governments as well as

diaspora organizations, who have the opportunity to

participate in the development of regulations, determine the

agenda of diaspora policy and directly influence the

implementation of this policy. One of the most important

participants that represents the diaspora organizations in

these processes is the World Federation of Free Latvians

(PBLA). It serves as an umbrella organization to coordinate

the work of overseas associations of Latvians abroad as

well as a representative of the diaspora at the highest level.

One of the results of the Council’s work is the

development of a Plan for Work with the Diaspora for

2021-2023, which became the first cross-sectoral policy

planning document, containing objectives, expected results,

performance indicators and deadlines for the

implementation of all institutions related to diaspora issues.

3.2 Ukrainian Perspective

The situation with diaspora policy in Ukraine is somewhat

different. Despite the significant number of representatives

of the Ukrainian diaspora and high rates of emigration in

recent decades, Ukraine has failed to formulate and

implement a more or less full-fledged policy on the

diaspora. The reasons for this include the predominance of

domestic policy issues on the agenda, institutional

weakness, conflicts within the political elite, and so on. For

a long time, interaction with diaspora was considered by the

Ukrainian government mainly in the cultural and

educational context, implementing state programs to

establish cultural ties with the diaspora and strengthen the

affiliation of Ukrainians abroad with Ukraine, but these

were sporadic measures that couldn’t make a significant

difference in relations with compatriots outside Ukraine,

and more difficult was to gain political or economic

benefits from it. Only after experiencing a serious political

crisis, unfolding of a military conflict in Ukraine and the

subsequent economic downturn, has the Ukrainian

government become increasingly aware of the benefits and

advantages of involving diaspora and its ability to act as a

soft power in the international arena. Therefore, at the

moment, Ukraine can be described as a country that is

finding its way to diaspora politics and diplomacy.

The urgent importance of this issue is due to the

significant quantitative indicators of the Ukrainian

diaspora. According to European Union Global Diaspora

Facility, there are 5,901,067 people outside Ukraine, who

make a significant contribution to the country’s economy

ISC SAI 2022 - V International Scientific Congress SOCIETY OF AMBIENT INTELLIGENCE

172

through remittances of 13.6% of GDP (according to

EUGDF).

Table 2: Top countries of the Ukrainian diaspora

destination.

Host country Number of Ukrainian

nationals abroad

Russia 3,269,248

USA 414,206

Kazakhstan 353,225

Italy 246,367

Germany 241,486

If we take into account the “old” diaspora, the numbers

are more impressing: there are more than 20 million people

living outside Ukraine who position themselves as

Ukrainians (UWC, 2021). The particular political urgency

of the issue is caused by the fact that the largest Ukrainian

diaspora is in Russia, which needs special attention from

the government.

We cannot but mention that in terms of terminology,

Ukraine deviates somewhat from the concept of “diaspora”,

instead using the concept of “foreign Ukrainians” in

legislation and policy documents. Thus, in the relevant law,

a foreign Ukrainian is defined as “a person who is a citizen

of another state or a stateless person, as well as a Ukrainian

ethnic origin or origin from Ukraine”. Moreover, this

concept is quite formalized, because the law prescribes a

clearly defined application process and the procedure for

obtaining the status of a foreign Ukrainian. Every foreign

citizen or stateless person of Ukrainian origin can obtain a

special certificate of a foreign Ukrainian, which helps to

keep records of Ukrainian nationals outside the home

country. Recently, the government has proposed several

improvements in the process of registering the Ukrainian

diaspora, having introduced a specially designed

smartphone app, as well as the possibility of foreign citizens

to voluntarily register as a Ukrainian living abroad to

receive assistance from Ukraine in emergencies.

The set of tasks that the Law on Foreign Ukrainians

assigns to the main promoter of relations with the diaspora,

the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, is quite revealing. The tasks

on the list include: to establish cooperation with foreign

Ukrainians, to help meet their national, cultural, educational

and linguistic needs etc., i.e. mostly culturally oriented

goals of a reactive nature. This formulation and respective

policy imply the perception of the diaspora as an object in

need of protection and assistance in meeting needs, rather

than a self-sufficient entity capable of transmitting values

and messages of various kinds (not just cultural) among

foreign countries.

One of the basic documents defining the priorities of

Ukraine’s diaspora policy was the National Concept of

Cooperation with Foreign Ukrainians (2006), which

enshrines the values and priorities in cooperation with

Ukrainian nationals abroad, but does not provide specific

mechanisms for their implementation. The vehicle to

implement it was initiated by the Ukrainian government in

the form of short-term programs and plans for relations with

foreign Ukrainians. Thus, during 2018-2020, a number of

such documents were adopted, within which the diaspora

policy is embedded within the framework of migration

policy and protecting rights of foreign Ukrainians abroad.

So, there is a gap in the policy implementation chain: the

concept is followed by the tactics of implementation, while

the strategy that should link the two is omitted.

In 2021, the Ukrainian government presented a draft of

the Concept of the State Target Program of Cooperation

with Foreign Ukrainians for the period up to 2023.

Recognizing the potential of Ukraine’s multimillion

Ukrainian community abroad to effectively advance

Ukraine’s national interests abroad, the concept focuses on

supporting and meeting the needs of foreign Ukrainians by

the state, which aims to establish long-term, systematic

relationships and integrated policies for diaspora. The

project provides for the possibility of establishing a central

executive body or involving the relevant central and local

authorities to coordinate cooperation with foreign

Ukrainians.

The institutionalization issue covers the need of

coordinating diaspora organizations as well. According to

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ukrainian diplomatic

institutions cooperate with more than 500 public

associations of foreign Ukrainians of various orientations.

Among them, the largest is the World Congress of

Ukrainians claimed to be a coordination superstructure of

Ukrainian communities in the diaspora with broad

functions and areas of concern. Although the organization

was founded in 1967, Ukrainian government has not still

worked out the institutional mechanism to coordinate with

the organization considered to be a global voice of

Ukrainian diaspora. Nowadays, the progress of cooperation

with the World Congress of Ukrainians is on the stage of

signed Memorandum of Cooperation.

The existing infrastructure of diaspora relations in

Ukraine has a number of drawbacks: there is a lack of

coordination between legislative acts and government

programs. It is the result of the absent holistic vision of

diaspora strategy as a systematic policy aimed at

developing and managing relations between homeland and

diasporic populations.

According to Lapshyna (2019), the main obstacle to

building diaspora diplomacy and full-fledged involvement

of diaspora in Ukraine is the government’s underestimation

of the diaspora’s contribution to the development of the

country. A number of serious political and economic crises

in Ukraine have been factors in mobilizing and increasing

the cohesion of Ukrainians living abroad. They became

more involved in Ukrainian affairs and claimed to hold a

legitimate stake in them. In addition, the Ukrainian diaspora

has sufficient resources and power, and, last but not least, a

desire to interact with the home country. However, Ukraine

fails to capitalize on the willingness of its diaspora to

engage in its domestic and foreign policy. In the absence of

a coherent and comprehensive diaspora policy, adequate

government infrastructure, functioning channels for

interaction and established relations and trust in

government, these aspirations remain unrealized.

Diaspora Diplomacy: Contemporary Problems of Countries in the Sustainable Development Context

173

3.3 Diaspora Engagement in

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan has also begun to pay attention to the

diaspora and take the first steps in developing a

diaspora policy.

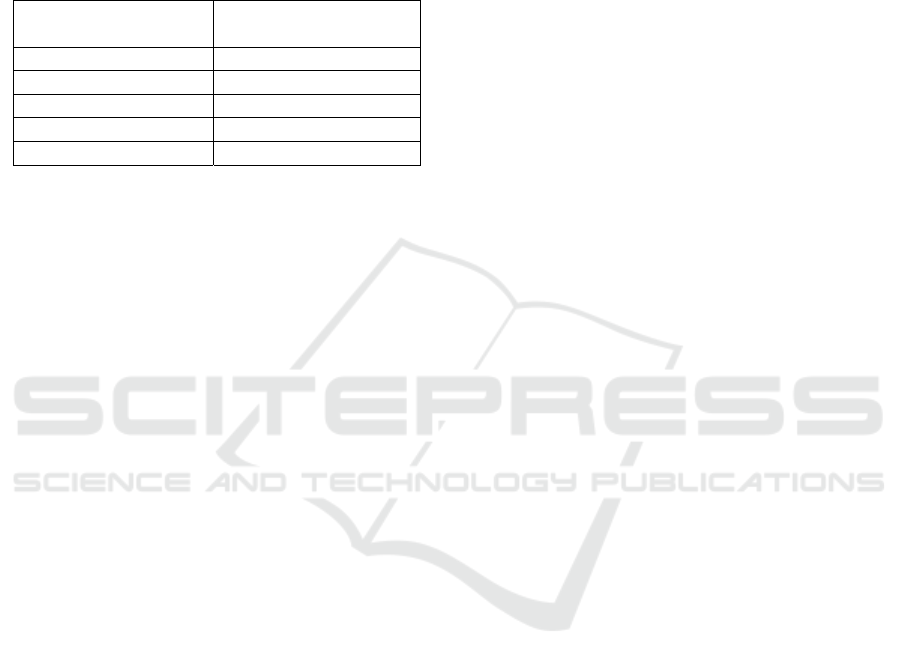

Table 3: Top countries of the Uzbekistan diaspora

destination.

Host country Number of Uzbek

nationals abroad

Russia 1,146,535

Kazakhstan 294,395

Ukraine 222,012

Turkmenistan 67,075

USA 66,093

Despite the fact that, according to the European

Union Global Diaspora Facility, the percentage of

emigrants from the total population of Uzbekistan is

only 6% (1,979,523 people), their contribution to

GDP is significant - about 12%, which is almost $7

million.

Uzbekistan also does not adhere to the concept of

“diaspora” in the legislation, using the term

“compatriot” instead. It covers people who were born

or previously lived in Uzbekistan (and their

descendants) who are not citizens of Uzbekistan and

live abroad. It also includes foreign nationals or

stateless persons who identify themselves as Uzbeks

or Karakalpaks and want to maintain ties with their

historical homeland.

The main goals of the state policy on cooperation

with compatriots are set by the Resolution of the

President of the Republic of Uzbekistan of October

25, 2018 No. PP-3982 on “measures for further

enhancement of the state policy of the Republic of

Uzbekistan in the sphere of cooperation with

compatriots living abroad”. The document contains

general directions for cooperation with foreign

Uzbeks, such as promoting their rights and freedoms,

preserving cultural and spiritual heritage, maintaining

ties and encouraging investment in Uzbekistan, etc.

Specific implementation of these goals is provided by

the National Concept of the State Policy of the

Republic of Uzbekistan in the Field of Interethnic

Relations and the Road Map on Its Implementation in

2019-2021.

Cooperation with compatriots is carried out

through The Committee for Inter-Ethnic and Friendly

Relations with Foreign Countries under the Cabinet

of Ministers of the Republic of Uzbekistan. However,

the broad orientation of this committee, which

includes foreign organizations and international

associations, hinders targeted communication with

diaspora representatives and prevents it from

functioning as an effective diaspora policy institution.

An important aspect of Uzbek diaspora policy is the

regulation of labor migration, protection of the rights

of Uzbek migrants, and so on. Thus, in 2020 the

Presidential Decree on Measures to Introduce a

System of Safe, Orderly and Legal Labor Migration

was introduced. It provides new standards and

conditions for those who go to work abroad (training

and certification, insurance, financial and social

support) as well as labor migrants returning from

foreign countries (reintegration, professional

development etc.). An important innovation in recent

years is the government’s strategy to encourage

Uzbek high-skilled professionals who live abroad to

return home. The emergence of this goal in the list of

government priorities can be considered the starting

point of a conscious policy of diaspora engagement.

This can be traced in several initiatives aimed at

engaging the foreign Uzbek nationals to dialogue and

discussion on the development strategy of

Uzbekistan. Among them - the creation in 2018 of the

expert council Buyuk Kelajak, the establishment of

the El-Yurt Umidi Foundation and more. Moreover,

a number of highly qualified Uzbek nationals from

abroad have taken up various positions in Uzbek

government.

Despite the intensification of efforts on diaspora

diplomacy, the challenge for Uzbekistan is to launch

effective mechanisms for their implementation and to

establish productive cooperation between

government agencies and diaspora organizations.

This is partly due to the lack of a long-term strategy

in this field, as well as the issue of trust between the

state and Uzbeks abroad.

3 CONCLUSIONS

States continue to view diaspora as a means of

promoting their national interests abroad and

attracting the resources available to diaspora for their

benefit. However, the tendency to build relations with

diaspora as an independent political entity with its

own interests, set of tools and spheres of influence is

becoming more and more pronounced, which leads to

the crystallization of the diplomatic subjectivity of

diaspora. The point of entry of diaspora into the

modern diplomatic configuration are strategies within

public diplomacy and the so-called “new diplomacy”

of plural actors.

ISC SAI 2022 - V International Scientific Congress SOCIETY OF AMBIENT INTELLIGENCE

174

Given its specificity as an emerging non-state

actor, diaspora contributes to the extension of

diplomatic tools to achieve goals, and contests

acknowledged practices and notions in diplomacy

and international politics, thus changing traditional

notions of diplomacy. Combining the world of

domestic and foreign policy, diaspora is the political

subjectivity of liminal nature, and this borderline

position can be a source of innovation and new

transformations in international politics.

Diaspora diplomacy performs an important

function of introducing the country to other countries

and keeping it in touch with the world. It is performed

through the communication and mediation activities

as well as representation of a nation-brand in both

political, culture and interpersonal areas.

The development of a strategy for interaction with

diaspora is an individual process in the case of each

country. The influencing factors include historical

and cultural background, history of relations between

the state and the diaspora, coherence of diaspora

political strategies with government policy in the

home country, and the availability and degree of

development of legitimate channels for

communication and interaction.

The efforts towards institutionalization of

diaspora diplomacy show that the country’s diaspora

community is gaining significance in foreign policy

strategy. Building institutions and infrastructure to

foster the relations with diaspora testifies both

changes of perspectives towards diaspora on the local

level and systemic shifts in global policy-making

discourse.

Latvia is one of the countries in the process of

developing and implementing diaspora diplomacy.

This is evidenced by the number of efforts made to

create the legislative and organizational infrastructure

of diaspora policy, laid foundations for the

institutionalization of diaspora relations, providing

channels of bilateral communication with its

members and more. Thanks to conscious and

purposeful government efforts, the Latvian diaspora

community has the opportunity to directly influence

political life through its voting rights and dual

citizenship, engage in mutually beneficial

cooperation in various sectors of interest, and actively

influence its own status, both internationally and in

the home country. An important achievement of the

development of diaspora diplomacy is the creation of

a separate diaspora legislative framework in the form

of the Diaspora Law, as well as a range of

mechanisms and tactics aimed at implementing its

provisions and subordinated to the overall diaspora

strategy.

Despite the number of laws and histories of the

implementation of programs to establish relations

with Ukrainians abroad, in Ukraine there is no holistic

vision of diaspora policy and the tasks it can perform.

As a result of scattered, mostly culturally oriented

initiatives, overlooking the potential positive impact

of multilevel relations with diaspora, ignoring the role

of diaspora as a means and actor of diplomacy,

Ukraine does not currently have a comprehensive

diaspora engagement policy. Critical to the creation

of a full-fledged diaspora diplomacy in Ukraine is the

need to pursue a proactive, holistic strategic policy to

engage the diaspora as part of the foreign policy

strategy. Relations with diaspora communities will be

effective if they are carried out on many levels and

are not tied to the courses of political forces.

Diaspora policy has also been on the agenda of the

Uzbek government, which is working to establish ties

with Uzbeks abroad. There are a number of pieces of

legislation in the country that regulate relations with

the diaspora, but they are either culturally oriented, as

in the case of Ukraine, or focused on regulating labor

migration. A notable trend is the government’s efforts

to involve highly qualified specialists of Uzbek origin

in the development of the country’s development

strategy, based on the “brain gain” policy. However,

these initiatives remain largely unfulfilled and the

diaspora policy infrastructure remains in its infancy

due to the lack of a self-sufficient long-term and

proactive strategy for diaspora engagement as well as

the lack of atmosphere of trust and cooperation.

When considering relations with diasporas of

Latvia, Ukraine and Uzbekistan, we took into account

only the “external” dimension of this concept. At the

same time, the so-called “internal diasporas” -

representatives of other countries living in their

territory - can exercise no less influence on state

development. This aspect needs a separate study,

because different mechanisms for promoting

relations and interaction are enacted.

REFERENCES

Aikins, K., White, N. 2011. Global Diaspora Strategies

Toolkit. Diaspora Matters, Dublin, Ireland.

Birka, I. Kļaviņš, D. 2019. Diaspora diplomacy: Nordic and

Baltic perspective. Diaspora Studies, DOI:

10.1080/09739572.2019.1693861

Bravo, V. 2015. The importance of diaspora communities

as key publics for national governments around the

world. In G. J. Golan, S-U. Yang, D. F. Kinsey (eds)

International Public Relations and Public Diplomacy

Communication and Engagement. New York. P.279-

296.

Diaspora Diplomacy: Contemporary Problems of Countries in the Sustainable Development Context

175

Brinkerhoff, J. M. 2012. Creating an Enabling Environment

for Diasporas’ Participation in Homeland

Development. International Migration 50 (1): 75–95.

Brubaker, R. 2005. The ‘diaspora’ diaspora. Ethnic and

racial studies 28(1): 1–19.

Cornago, N. 2013. Plural Diplomacies: Normative

Predicaments and Functional Imperatives. Leiden:

Brill.

Docker, J. 2001. 1492 The Poetics of Diaspora: Literature

Culture And Identity. London Continuum.

Dolea, A. 2015. The Need for Critical Thinking in Country

Promotion. In J. L’Etang et al. (eds.), The Routledge

Handbook of Critical Public Relations. New York,

Routledge.

EUGDF. Diaspora Engagement Map. European Union

Global Diaspora Facility.

https://diasporafordevelopment.eu/interactive-map/

Ho, E. L. E., & McConnell, F. 2019. Conceptualizing

‘diaspora diplomacy’: Territory and populations

betwixt the domestic and foreign. Progress in Human

Geography, 43(2), 235–255.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517740217

Hocking, B. 2005. Rethinking the ‘New’ Public

Diplomacy. In J. Melissen (ed) The New Public

Diplomacy: Soft Power in International Relations.

Palgrave Macmillan. 28-46.

Ionescu, D. 2006. Engaging Diasporas as Development

Partners for Home and Destination Countries:

Challenges for Policymakers (IOM Migration Research

Series Paper No. 26). International Organization for

Migration.

Jimenez, R. M. 2019. Public diplomacy and SDGs. SDGs

as a goal and a means of public diplomacy. In: SDGs,

Main Contributions and Challenges. United Nations

Organization. https://doi.org/10.18356/c6934888-en

Koslowski, R. 2005. International migration and the

globalization of domestic politics: A conceptual

framework. In R. Koslowski (Ed.), International

migration and the globalization of domestic politics (5–

32). Transnationalism. London: Routledge.

Lapshyna, I. 2019. Do Diasporas Matter? The Growing

Role of the Ukrainian Diaspora in the UK and Poland

in the Development of the Homeland in Times of War.

Central and Eastern European Migration Review 8(1):

51-73. doi: 10.17467/ceemr.2019.04

Melissen, J. 2013. Public diplomacy. In A.C. Cooper, J.

Heine R. Thakur (eds) The Oxford Handbook of

Modern Diplomacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press,

436–52.

Melissen, J., Wang, J. 2019. Introduction: Debating Public

Diplomacy. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 14(1-2),

1-5.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Republic of Latvia. Plan for

Work with the Diaspora for 2021-2023.

https://www.mfa.gov.lv/en/media/3308/download

Shain, Y., Barth, A. 2003. Diasporas and International

Relations. Theory. International Organization,57(3),

449-479. doi:10.1017/S0020818303573015

Sheludiakova, N., Mamurov, B., Maksymova, I.,

Slyusarenko, K., Yegorova, I. 2021. Communicating

the Foreign Policy Strategy: on Instruments and Means

of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine. SHS Web

Conf. 100 02005. DOI:

10.1051/shsconf/202110002005

UWC. 2021. Annual Report. Ukrainian World Congress.

https://issuu.com/ukrainianworldcongress/docs/uwc-

2021-annual-report-en-23-pages-rev6

ISC SAI 2022 - V International Scientific Congress SOCIETY OF AMBIENT INTELLIGENCE

176