Insertion of Real Agents Behaviors in CARLA Autonomous Driving

Simulator

Sergio Mart

´

ın Serrano

1 a

, David Fern

´

andez Llorca

1,2 b

, Iv

´

an Garc

´

ıa Daza

1 c

and Miguel

´

Angel Sotelo

1 d

1

Computer Engineering Department, University of Alcal

´

a, Alcal

´

a de Henares, Spain

2

European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC), Seville, Spain

Keywords:

Automated Driving, Autonomous Vehicles, Predictive Perception, Behavioural Modelling, Simulators, Virtual

Reality, Presence.

Abstract:

The role of simulation in autonomous driving is becoming increasingly important due to the need for rapid

prototyping and extensive testing. The use of physics-based simulation involves multiple benefits and advan-

tages at a reasonable cost while eliminating risks to prototypes, drivers and vulnerable road users. However,

there are two main limitations. First, the well-known reality gap which refers to the discrepancy between

reality and simulation that prevents simulated autonomous driving experience from enabling effective real-

world performance. Second, the lack of empirical knowledge about the behavior of real agents, including

backup drivers or passengers and other road users such as vehicles, pedestrians or cyclists. Agent simulation

is usually pre-programmed deterministically, randomized probabilistically or generated based on real data,

but it does not represent behaviors from real agents interacting with the specific simulated scenario. In this

paper we present a preliminary framework to enable real-time interaction between real agents and the simu-

lated environment (including autonomous vehicles) and generate synthetic sequences from simulated sensor

data from multiple views that can be used for training predictive systems that rely on behavioral models. Our

approach integrates immersive virtual reality and human motion capture systems with the CARLA simulator

for autonomous driving. We describe the proposed hardware and software architecture, and discuss about the

so-called behavioural gap or presence. We present preliminary, but promising, results that support the poten-

tial of this methodology and discuss about future steps.

1 INTRODUCTION

The recent explosion in the use of simulators for rapid

prototyping and testing of autonomous systems has

occurred primarily in the field of autonomous vehi-

cles. This is mostly due to the compelling need for

extensive validation, as real test-driving alone cannot

provide sufficient evidence for demonstrating their

safety (Kalra and Paddock, 2016). The relative ease

of generating massive data for training and testing, es-

pecially edge cases, having full control over all the

variables under study (e.g., street layout, lighting con-

ditions, traffic scenarios), makes its use very attrac-

tive. In addition, the generated data is annotated by

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8029-1973

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2433-7110

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8940-6434

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8809-2103

design including semantic information.

But the use of virtual-world data also brings with

it some challenges. The realism of the simulated sen-

sor data (i.e., radar, LiDAR, cameras) and the physi-

cal models are critical aspects to minimize the reality

gap. Advances in this area are very remarkable, and

highly realistic synthetic data has been shown to be

useful for improving different perception tasks such

as pedestrian detection (V

´

azquez et al., 2014), seman-

tic segmentation (Ros et al., 2016) or vehicle speed

detection (Martinez et al., 2021). However, despite

efforts to generate realistic synthetic behaviors of road

agents (e.g., to address trajectory forecasting (Weng

et al., 2021)), simulation lacks empirical knowledge

about the behavior of other road users (e.g., vehicles,

pedestrians, cyclists), including behavior and motion

prediction, communication, and human-vehicle inter-

action (Eady, 2019).

In this paper, we present a new approach to in-

Serrano, S., Llorca, D., Daza, I. and Sotelo, M.

Insertion of Real Agents Behaviors in CARLA Autonomous Driving Simulator.

DOI: 10.5220/0011352400003323

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications (CHIRA 2022), pages 23-31

ISBN: 978-989-758-609-5; ISSN: 2184-3244

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

23

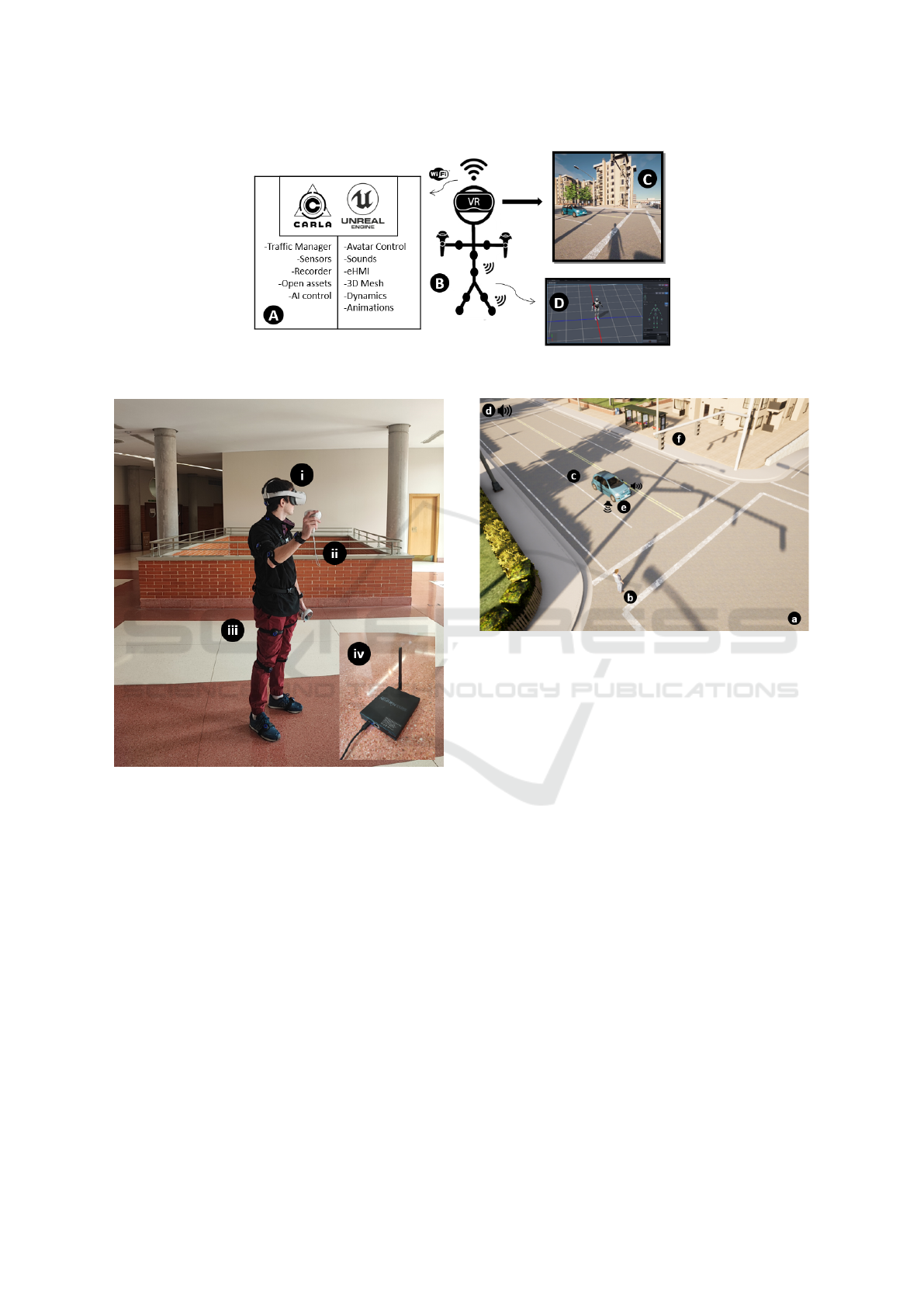

Figure 1: Overview of the presented approach. (1) CARLA-Unreal Engine is provided with the head (VR headset) and

body (motion capture system) pose. (2) The scenario is generated, including the autonomous vehicles and the digitized

pedestrian. (3) The environment is provided to the pedestrian (through VR headset). (4) Autonomous vehicle sensors perceive

the environment, including the pedestrian.

corporate real agents behaviors and interactions in

CARLA autonomous driving simulator (Dosovitskiy

et al., 2017) by using immersive virtual reality and hu-

man motion capture systems. The idea is to integrate a

subject in the simulated scenarios using CARLA and

Unreal Engine 4 (UE4), with real time feedback of

the pose of his head and body, and including posi-

tional sound, trying to generate an experience realis-

tic enough for the subject to feel physically present

in the virtual world and accept it at a subconscious

level (i.e., maximize virtual reality presence). At the

same time, the captured pose and motion of the sub-

ject is integrated into the virtual scenario by means

of an avatar, so that the simulated sensors of the au-

tonomous vehicles (i.e., radar, LiDAR, cameras) can

be aware of their presence. This is very interesting

because it allows, on the one hand, to obtain syn-

thetic sequences from multiple points of view based

on the behavior of real subjects, which can be used

to train and test predictive perception models. And

on the other hand, they also allow to address different

types of interaction studies between autonomous ve-

hicles (i.e., software in the loop) and real subjects, in-

cluding external human-machine interfaces (eHMI),

in fully controlled conditions and with total safety. To

our knowledge, this is the first attempt to integrate the

behaviors of real road agents into an autonomous ve-

hicle simulator for these purposes.

2 RELATED WORK

In the following, we summarize the most relevant

works that have proposed the use of virtual reality and

simulators for vulnerable road users (mainly pedestri-

ans and cyclists) in the context of automated driving.

Since the visual realism of simulators has improved

greatly in recent years, we focus on relatively recent

work, as the conclusions obtained with less realistic

simulators are not entirely applicable to the current

context.

Most of the previous works proposed the use of

virtual reality and simulators to study pedestrian be-

havior in scenarios where they have to interact with

an autonomous vehicle (high levels of automation

(Fern

´

andez-Llorca and G

´

omez, 2021)) including the

perception of distances and the intention to cross

(Doric et al., 2016), (Deb et al., 2017), (Iryo-Asano

et al., 2018), (Bhagavathula et al., 2018), (Farooq

et al., 2018), (Nu

˜

nez Velasco et al., 2019).

Additionally, these approaches have recently

been used to study the communication between au-

tonomous vehicles and pedestrians, including accep-

tance and behavioral analysis of various eHMI sys-

tems (Chang et al., 2017), (Holl

¨

ander et al., 2019),

(Deb et al., 2020), (Gruenefeld et al., 2019), (L

¨

ocken

et al., 2019), (Nguyen et al., 2019). Virtual environ-

ments allow experimentation with multiple types of

eHMI systems, and with multiple types of vehicles in

a relatively straightforward fashion.

We can find similar studies for the case of cyclists,

based on simulation platforms and immersive virtual

reality (Ullmann et al., 2020), usually to analyze the

perceptions and behavior of cyclists to various envi-

ronmental variables (Xu et al., 2017), (Nu

˜

nez Velasco

et al., 2021), (Nazemi et al., 2021).

The aforementioned studies have not considered

the use of motion capture systems to integrate visual

CHIRA 2022 - 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

24

CARLA Server

UE4

sockets

CARLA Client

Sound

module

3

eHMI

4

Pedestrian and traffic

scenario design

5

Avatar Control

- Oculus Quest 2

- Motion controllers

1

Full body tracking

- Perception Neuron

Studio

2

Real Agents Insertion (Subject)

Figure 2: System Block Diagram.

body feedback into the simulation. This is an im-

portant factor for two main reasons. First, a fully-

articulated visual representation of the users in the

immersive virtual environment can enhance their sub-

jective sense of feeling present in the virtual world

(Bruder et al., 2009). Second, and more important

for our purpose, the articulated representation of the

pedestrian pose (body, head, and even hands) within

the simulator allows, on the one hand, to integrate the

user within the simulated scenario and to be detected

by the sensors of the autonomous vehicles, allowing

the generation of data sequences that can be very use-

ful for training and testing predictive models. On the

other hand, it allows real-time interaction between the

autonomous vehicle and the pedestrian (i.e., software

in the loop), which can be very useful to test edge

cases.

In some studies, user-autonomous vehicle interac-

tion is not possible, as they rely on the projection of

prerecorded 360º videos (i.e., 360º video-based vir-

tual reality (Nu

˜

nez Velasco et al., 2019), (Nu

˜

nez Ve-

lasco et al., 2021)). While this approach certainly

enhances visual realism, it does not enable interac-

tion. But even with the use of simulators, we have

found only one paper (Gruenefeld et al., 2019) that

attempts some kind of interaction between the pedes-

trian and the autonomous vehicle via hand gestures

(i.e. stop gesture). However, the gesture detection

process of the autonomous vehicle in the simulator

does not seem to be related to the integration of the

user in the virtual scenario.

Finally, regarding open source autonomous driv-

ing simulators we find several options such as

CARLA (Dosovitskiy et al., 2017), AirSim (Shah

et al., 2018) or DeepDrive (DeepDrive, 2018), with

CARLA and AirSim being probably the ones that

are receiving more attention and have experienced

the largest growth in recent years. Although Air-

Sim works natively with virtual reality (originally in-

tended as flight simulator), CARLA does not support

virtual reality natively. The introduction of immersive

virtual reality with CARLA has only recently been

proposed for the driver use case (Silvera et al., 2022).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work

that provides a solution to integrate subjects into the

CARLA simulator using immersive virtual reality for

the vulnerable road users case, including motion cap-

ture, visual body feedback and integration of the ar-

ticulated human pose into the simulator.

3 VR IMMERSION FEATURES

This section describes the features of the immersive

virtual reality system in the CARLA simulator for

autonomous driving. Full pedestrian immersion is

achieved by making use of the functionality provided

by UE4 and external hardware, such as VR glasses

and a set of motion sensors, for behaviour and inter-

action research.

The CARLA open-source simulator is imple-

mented over UE4, which provides high rendering

quality, realistic physics and an ecosystem of inter-

operable plugins. CARLA simulates dynamic traffic

scenarios and provides an interface between the vir-

tual world created with UE4 and the road agents op-

erating within the scenario. CARLA is designed as

a server-client system to make this possible, where

the server runs the simulation and renders the scene.

Communication between the client and the server is

done via sockets.

The main features for the insertion of real agent

behaviours in the simulation are based on five points

(depicted in Fig. 2): 1) Avatar control: from the

CARLA’s blueprint library that collects the architec-

ture of all its actors and attributes, we modify the

pedestrian blueprints to create an immersive and ma-

neuverable VR interface between the person and the

virtual world; 2) Body tracking: we use a set of iner-

tial sensors and proprietary external software to cap-

Insertion of Real Agents Behaviors in CARLA Autonomous Driving Simulator

25

ture the subject’s motion through the real scene, and

motion perception: we integrate the avatar’s mo-

tion into the simulator via .bvh files; 3) Sound de-

sign: since CARLA is an audio-less simulator, we in-

troduce positional sound into the environment to en-

hance the immersion of the person; 4) eHMI integra-

tion: enabling the communication of state and intent

information from autonomous vehicles to address in-

teraction studies; 5) Scenario simulation: we design

traffic scenarios within CARLA client, controlling the

behaviour of vehicles and pedestrians.

3.1 Avatar Control

CARLA’s blueprints (that include sensors, static ac-

tors, vehicles and walkers) have been specifically de-

signed to be managed through the Python client API.

Vehicles are actors that incorporate special internal

components that simulate the physics of wheeled ve-

hicles and can be driven by functions that provide

driving commands (such as throttle, steering or brak-

ing). Walkers are operated in a similar way and its be-

havior can be directed by a controller. However, they

are not designed to adopt real behaviors and therefore

do not include wide range of unexpected movements

and an immersive interface.

We modify a walker blueprint to make an IK setup

(inverse kinematics) for VR (full body room-scale) to

support this. The tools available to capture the real

human movement are the following: a) Oculus Quest

2 (for head tracking and user position control), and

b) Motion controllers (for both hands tracking). Ocu-

lus Quest 2 already has a safety distance system, de-

limiting the playing area through which the performer

can move freely. The goal is to allow the performer

to move within the safety zone that s/he has estab-

lished, corresponding to a specific area of CARLA’s

scenario.

The first step to achieve immersion is to modify

the blueprint of the walker by attaching a virtual cam-

era to its head to get a first-person feeling. The camera

functions as the spectator’s vision, while the skele-

tal mesh defines the appearance the walker adopts.

The displacement and perspective of the walker are

activated, from certain minimum thresholds, with the

translation and rotation of the VR headset, which are

applied to the entire skeletal mesh. In addition, the

VR glasses and both motion controllers adapt the pose

of the neck and hand in real time.

VR immersion for pedestrians is provided by im-

plementing a head-mounted display (HMD) and cre-

ating an avatar in UE4. The subject wearing the VR

glasses and controlling the avatar has complete free-

dom of movement within the preset area where we

conduct the experiments.

3.2 Full-body Tracking

To control the avatar (i.e., to represent the movement

and pose of the subject inside the simulator), head

(VR headset) and hand (motion controllers) tracking

are not enough. Some kind of motion capture (Mo-

Cap) system is needed. There are multiple options,

including vision-based systems with multiple cam-

eras and inertial measurement units (Menolotto et al.,

2020). In our case, an inertial wireless sensor sys-

tem has been chosen, namely the Perception Neuron

Studio (PNS) motion capture system (Noitom, 2022),

as a compromise solution between accuracy and us-

ability. Each MoCap system includes a set of inertial

sensors and straps that can be put on the joints easily,

as well as a software for calibrating and capturing pre-

cise motion data. It also allows integration with other

3D rendering and animation software, such as iClone,

Blender, Unity or UE4.

3.3 Sound Design

Other techniques for total immersion, such as sound

design and real-world isolation, are other important

aspects of behavioral research. World audio is absent

in the CARLA simulator, but it is essential for inter-

action with the environment, as humans use spatial

sound cues to track the location of other actors and

predict their intentions.

We incorporate positional audio into the simula-

tor, attaching a sound to each agent participating in

the scene. Walking and talking sounds are assigned

for pedestrians, and engine sounds parameterized by

throttle and brake for vehicles. In addition, we add

environmental sounds such as birds singing, wind and

traffic sounds.

3.4 External Human-Machine

Interfaces (eHMI)

Communication between road users is an essential

factor in traffic environments. In our experiments we

include external human-machine interfaces (eHMI)

for autonomous vehicles to communicate their sta-

tus and intentions to the actual road user. The pro-

posed eHMI design consists of a light strip along the

entire front of the car, as depicted in Fig. 3. This

allows studying the influence of the interface on de-

cision making when the pedestrian’s trajectory con-

verges with the one followed by the vehicle in the vir-

tual scenario.

CHIRA 2022 - 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

26

Figure 3: Left: vehicle without eHMI. Right: vehicle with

eHMI activated.

3.5 Traffic Scenario Simulation

CARLA offers different options to simulate traffic

and specific traffic scenarios. We use the Traffic Man-

ager module to populate a simulation with realistic ur-

ban traffic conditions. The control of each vehicle is

carried out in a specific thread. Communication with

other layers is managed via synchronous messaging.

We can control traffic flow by setting parameters

that enforce specific behaviors. For example, cars can

be allowed to exceed speed limits, ignore traffic light

conditions, ignore pedestrians, or force lane changes.

The subject is integrated into the simulator on a

map that includes a 3D model of a city. Each map is

based on an OpenDRIVE file that describes the fully

annotated road layout. This feature allows us to de-

sign our own maps and reproduce the same traffic sce-

narios in real and virtual environments, to evaluate the

integration of real behavior in the simulator and to be

able to carry out presence studies by comparing the

results of the interaction.

3.6 Recording, Playback and Motion

Perception

When running experiments, simulation data must be

recorded and replayed for later analysis. CARLA has

a native record and playback system that serializes

the world information in each simulator tick for post-

simulation recreation. However, this is only intended

for tracking actors managed by the Python API and

does not include the subject avatar or motion sensors.

Along with the recording of the state of the

CARLA world, in our case the recording and play-

back of the actual full-body motion of the subject is

essential. In our approach we use the Axis Studio

software provided by Perception Neuron to record the

body motion during experiments where the subject

has to interact with the traffic scene in virtual reality.

The recording is then exported in a .bvh file which is

subsequently integrated into the UE4 editor.

Once the interaction is recorded, the simulation is

played back so that the simulated sensors of the au-

tonomous vehicles (i.e., radar, LiDAR, cameras) not

only perceive the avatar’s skeletal mesh and its dis-

placement, but also the specific pose of all its joints

(i.e., body language).

4 SYSTEM IMPLEMENTATION

AND RESULTS

The overall scheme of the system is depicted in Fig.

4. In the following we describe the hardware and soft-

ware configurations and present preliminary results.

4.1 Hardware Setup

The overall hardware setup is shown in Fig. 5. During

experiments, we use the Oculus Quest 2 as our head-

mounted device (HMD), created by Meta, which has

6GB RAM processor, two adjustable 1832 x 1920

lenses, 90Hz refresh rate and an internal memory of

256 GB. Quest 2 features WiFi 6, Bluetooth 5.1, and

USB Type-C connectivity, SteamVR support and 3D

speakers. For full-body tracking we use PNS pack-

aged solution with inertial trackers. The kit includes

standalone VR headset, 2 motion controllers, 17 Stu-

dio Inertial Body sensors, 14 set of straps, 1 charging

case and 1 Studio Transceiver.

To conduct the experiments, we reserved a preset

area wide enough and free of obstacles where the sub-

ject can act as a real pedestrian inside the simulator.

Quest 2 and motion controllers are connected to PC

via Oculus link or WiFi as follows:

• Wired connection: via the Oculus Link cable or

other similar high quality USB 3.

• Wireless connection: via WiFi by enabling Air

Link from the Meta application, or using Virtual

Desktop and SteamVR.

The subject puts on the straps of the appropriate

length and places the PN Studio sensors into the

bases. The transceiver is attached to the PC via USB.

After launching the build version of CARLA for Win-

dows, Quest 2 enables ”VR Preview” in the UE4 edi-

tor.

4.2 Software Setup

VR Immersion System is currently dependent on

UE4.24 and Windows 10 OS due to CARLA build,

and Quest 2 Windows-only dependencies. Using TCP

socket plugin, all the actor locations and other useful

parameters for the editor are sent from the Python API

to integrate, for example, the sound of each actor or

the eHMI of the autonomous vehicle. ”VR Preview”

launches the game on the HMD.

Insertion of Real Agents Behaviors in CARLA Autonomous Driving Simulator

27

Figure 4: System Schematics. (A) Simulator CARLA-UE4. (B) VR headset, motion controllers and PN Studio sensors. (C)

Spectator View in Virtual Reality. (D) Full-body tracking in Axis Studio.

Figure 5: Hardware setup. (i) VR headset (Quest 2): trans-

fer the image from the environment to the performer. (ii)

Motion controllers: allow control of the avatar’s hands.

(iii) PN Studio sensors: provide body tracking withstand-

ing magnetic interference. (iv) Studio Transceiver: receives

sensors data wirelessly by 2.4GHz.

Perception Neuron Studio works with Axis Studio

which supports up to 3 subjects at a time while man-

aging up to 23 sensors for the body and fingers.

4.3 Results

The safety of automated driving functions depends

highly on reliable corner cases detection. A recent re-

search work describes corner cases (CC) as data that

occur infrequently, represent a dangerous situation

and are sparse in the datasets (Daniel Bogdoll, 2021).

We aim to integrate behaviours of real subjects in the

generation of wide variety of scenarios with pedestri-

Figure 6: Simulation of Interactive traffic situations. (a)

3D world design. (b) Pedestrian matches the performer

avatar. (c) Autonomous vehicle. (d) Environment sounds

and agents sounds. (e) eHMI. (f) Traffic lights and traffic

signs.

ans involved, including CC, in order to provide train-

ing data with real-time interaction. The preliminary

scenario designed includes the interaction between a

single autonomous vehicle and a single pedestrian.

The vehicle circulates on the road when it reaches a

pedestrian crossing where the pedestrian shows clear

intentions to cross. The pedestrian receives informa-

tion on status and vehicle intentions through an eHMI

and can track its location by listening to the engine

sound. Lighting and weather conditions are favorable

(sunny day).

It is possible to spot the vehicle a few metres ahead

of the pedestrian crossing before starting the action.

When the pedestrian decides whether or not to wait

for the vehicle to come to a complete stop, s/he pays

attention to the speed and deceleration of the vehicle

before it reaches the intersection. Sensors attached to

the vehicle capture the image of the scene as shown in

Fig. 7, and detect the pedestrian as shown in LiDAR

point cloud in Fig. 8.

As a preliminary usability assessment, six real

subjects completed a 15-item presence scale consist-

CHIRA 2022 - 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

28

Figure 7: Cameras RGB / Depth / Segmentation.

Figure 8: LiDAR point cloud (ray-casting).

ing in five items for self-presence, five items for au-

tonomous vehicle presence and five items for environ-

mental presence. The questions raised are depicted in

Appendix A. In addition, we request subjective feed-

back about system usability and user experience.

Most of the participants felt a strong self-presence

(M=3.97, SD=0.528), fitting into the avatar’s body.

Nevertheless, some of them were skeptical of the

damage the avatar was exposed to (such as being run

over) and did not feel under any real threat. Regarding

autonomous vehicle presence (M=3.60, SD=0.657),

the engine’s sound composed the point of greatest dis-

agreement among the participants, since some found

it very useful to locate the vehicle, while others did

not even notice or found it annoying. The image of

the vehicle did not look completely clear-cut until the

vehicle was close enough to the avatar, and its stop

in front of the pedestrian cross did not feel threaten-

ing in the sense that its braking was appreciated too

conservative. The environmental presence (M=4.63,

SD=0.266) was felt very strongly by all the partici-

pants that felt really involved in an urban environment

and commented that adding other agents or more traf-

fic on the road would enhance the experience.

VR Immersion allows to integrate real participants

in interactive situations on the road and to use objec-

tive metrics (such as collisions and reaction times) in

order to measure interaction quality without real dan-

ger. CARLA enables custom traffic scenarios while

UE4 provides the immersive and interactive interface

into the same simulator.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we have presented a preliminary frame-

work to enable real-time interaction between real

agents and the simulated environment. At this level,

more results are expected from testing interactive traf-

fic scenes with multiple real participants.

Regarding the immersive sensation, the virtual en-

vironment displayed from the glasses varies between

15 and 20 fps, showing a stable image to the per-

former that allows him/her to interact with the world

of CARLA. The wireless connection is prioritized

over the wired connection, since it allows a greater

degree of freedom of movement. The performer pose

within the virtual environment is registered by Per-

ception Neuron, generating useful sequences to train

and validate predictive models to, for example, pre-

dict future actions and trajectories of traffic agents.

The scenario shown in this paper serves as a ba-

sis for a preliminary presentation of the proposed

methodology. From here, as future work, it is in-

tended, on the one hand, to carry out a study of pres-

ence, interaction and communication with equivalent

real and virtual environments. And on the other hand,

to develop a data recording campaign with multiple

subjects, different traffic scenarios and varied envi-

ronmental conditions, in order to generate a dataset

that can be used to train action and trajectory predic-

tion models.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was mainly supported by the Spanish

Ministry of Science and Innovation (Research Grant

PID2020-114924RB-I00) and in part by the Commu-

nity Region of Madrid (Research Grant 2018/EMT-

4362 SEGVAUTO 4.0-CM).

REFERENCES

Bhagavathula, R., Williams, B., Owens, J., and Gibbons, R.

(2018). The reality of virtual reality: A comparison of

pedestrian behavior in real and virtual environments.

Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics

Society Annual Meeting, 62(1):2056–2060.

Bruder, G., Steinicke, F., Rothaus, K., and Hinrichs, K.

(2009). Enhancing presence in head-mounted display

environments by visual body feedback using head-

mounted cameras. In 2009 International Conference

on CyberWorlds, pages 43–50.

Chang, C.-M., Toda, K., Sakamoto, D., and Igarashi, T.

(2017). Eyes on a car: an interface design for commu-

nication between an autonomous car and a pedestrian.

Insertion of Real Agents Behaviors in CARLA Autonomous Driving Simulator

29

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on

Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular

Applications (AutomotiveUI’17), pages 65–73.

Daniel Bogdoll, Jasmin Breitenstein, F. H. M. B. B. S. T.

F. J. M. Z. (2021). Description of corner cases in au-

tomated driving: Goals and challenges. arXiv.

Deb, S., Carruth, D. W., Fuad, M., Stanley, L. M., and Frey,

D. (2020). Comparison of child and adult pedestrian

perspectives of external features on autonomous vehi-

cles using virtual reality experiment. In Stanton, N.,

editor, Advances in Human Factors of Transportation,

pages 145–156. Springer International Publishing.

Deb, S., Carruth, D. W., Sween, R., Strawderman, L., and

Garrison, T. M. (2017). Efficacy of virtual reality

in pedestrian safety research. Applied Ergonomics,

65:449–460.

DeepDrive (2018). Deepdrive.

Doric, I., Frison, A.-K., Wintersberger, P., Riener, A.,

Wittmann, S., Zimmermann, M., and Brandmeier, T.

(2016). A novel approach for researching crossing be-

havior and risk acceptance: The pedestrian simulator.

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on

Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular

Applications (AutomotiveUI’16), pages 39–44.

Dosovitskiy, A., Ros, G., Codevilla, F., Lopez, A., and

Koltun, V. (2017). CARLA: An open urban driving

simulator. In Proceedings of the 1st Annual Confer-

ence on Robot Learning, pages 1–16.

Eady, T. (2019). Simulations can’t solve autonomous driv-

ing because they lack important knowledge about the

real world – large-scale real world data is the only

way.

Farooq, B., Cherchi, E., and Sobhani, A. (2018). Virtual

immersive reality for stated preference travel behav-

ior experiments: A case study of autonomous vehi-

cles on urban roads. Transportation Research Record,

2672(50):35–45.

Fern

´

andez-Llorca, D. and G

´

omez, E. (2021). Trustwor-

thy autonomous vehicles. Publications Office of

the European Union, Luxembourg,, EUR 30942 EN,

JRC127051.

Gruenefeld, U., Weiß, S., L

¨

ocken, A., Virgilio, I., Kun,

A. L., and Boll, S. (2019). Vroad: Gesture-based in-

teraction between pedestrians and automated vehicles

in virtual reality. In Proceedings of the 11th Interna-

tional Conference on Automotive User Interfaces and

Interactive Vehicular Applications: Adjunct Proceed-

ings, AutomotiveUI ’19, page 399–404.

Holl

¨

ander, K., Wintersberger, P., and Butz, A. (2019).

Overtrust in external cues of automated vehicles: An

experimental investigation. In Proceedings of the

11th International Conference on Automotive User In-

terfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications, page

211–221, New York, NY, USA. Association for Com-

puting Machinery.

Iryo-Asano, M., Hasegawa, Y., and Dias, C. (2018). Appli-

cability of virtual reality systems for evaluating pedes-

trians’ perception and behavior. Transportation Re-

search Procedia, 34:67–74.

Kalra, N. and Paddock, S. M. (2016). Driving to safety: how

many miles of driving would it take to demonstrate au-

tonomous vehicle reliability? Research report, RAND

Corporation.

L

¨

ocken, A., Golling, C., and Riener, A. (2019). How should

automated vehicles interact with pedestrians? a com-

parative analysis of interaction concepts in virtual re-

ality. In Proceedings of the 11th International Con-

ference on Automotive User Interfaces and Interac-

tive Vehicular Applications, AutomotiveUI ’19, page

262–274.

Martinez, A. H., D

´

ıaz, J. L., Daza, I. G., and Llorca, D. F.

(2021). Data-driven vehicle speed detection from syn-

thetic driving simulator images. In 2021 IEEE Inter-

national Intelligent Transportation Systems Confer-

ence (ITSC), pages 2617–2622.

Menolotto, M., Komaris, D.-S., Tedesco, S., O’Flynn, B.,

and Walsh, M. (2020). Motion capture technology in

industrial applications: A systematic review. Sensors,

20(19).

Nazemi, M., van Eggermond, M., Erath, A., Schaffner, D.,

Joos, M., and Axhausen, K. W. (2021). Studying bicy-

clists’ perceived level of safety using a bicycle simula-

tor combined with immersive virtual reality. Accident

Analysis & Prevention, 151:105943.

Nguyen, T. T., Holl

¨

ander, K., Hoggenmueller, M.,

Parker, C., and Tomitsch, M. (2019). Design-

ing for projection-based communication between au-

tonomous vehicles and pedestrians. In Proceedings of

the 11th International Conference on Automotive User

Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications, Au-

tomotiveUI ’19, page 284–294. Association for Com-

puting Machinery.

Noitom (2022). Perception neuron studio system.

Nu

˜

nez Velasco, J. P., de Vries, A., Farah, H., van Arem,

B., and Hagenzieker, M. P. (2021). Cyclists’ crossing

intentions when interacting with automated vehicles:

A virtual reality study. Information, 12(1).

Nu

˜

nez Velasco, J. P., Farah, H., van Arem, B., and Hagen-

zieker, M. P. (2019). Studying pedestrians’ crossing

behavior when interacting with automated vehicles us-

ing virtual reality. Transportation Research Part F:

Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 66:1–14.

Ros, G., Sellart, L., Materzynska, J., Vazquez, D., and

Lopez, A. M. (2016). The synthia dataset: A large col-

lection of synthetic images for semantic segmentation

of urban scenes. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Com-

puter Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pages

3234–3243.

Shah, S., Dey, D., Lovett, C., and Kapoor, A. (2018). Air-

sim: High-fidelity visual and physical simulation for

autonomous vehicles. In Hutter, M. and Siegwart, R.,

editors, Field and Service Robotics, pages 621–635.

Springer International Publishing.

Silvera, G., Biswas, A., and Admoni, H. (2022). Dreyevr:

Democratizing virtual reality driving simulation for

behavioural & interaction research.

Ullmann, D., Kreimeier, J., G

¨

otzelmann, T., and Kipke, H.

(2020). Bikevr: A virtual reality bicycle simulator to-

wards sustainable urban space and traffic planning. In

CHIRA 2022 - 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

30

Proceedings of the Conference on Mensch Und Com-

puter, MuC ’20, page 511–514. Association for Com-

puting Machinery.

V

´

azquez, D., L

´

opez, A. M., Mar

´

ın, J., Ponsa, D., and

Ger

´

onimo, D. (2014). Virtual and real world adap-

tation for pedestrian detection. IEEE Transac-

tions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence,

36(4):797–809.

Weng, X., Man, Y., Park, J., Yuan, Y., Cheng, D., O’Toole,

M., and Kitani, K. (2021). All-In-One Drive: A Large-

Scale Comprehensive Perception Dataset with High-

Density Long-Range Point Clouds. arXiv.

Xu, J., Lin, Y., and Schmidt, D. (2017). Exploring the in-

fluence of simulated road environments on cyclist be-

havior. The International Journal of Virtual Reality,

17(3):15–26.

APPENDIX A

Self-presence Scale Items

To what extent did you feel that. . . (1= not at all – 5

very strongly)

1. You could move the avatar’s hands.

2. The avatar’s displacement was your own displace-

ment.

3. The avatar’s body was your own body.

4. If something happened to the avatar, it was hap-

pening to you.

5. The avatar was you.

Autonomous Vehicle Presence Scale Items

To what extent did you feel that. . . (1= not at all – 5

very strongly)

1. The vehicle was present.

2. The vehicle dynamics and its movement were nat-

ural.

3. The sound of the vehicle helped you to locate it.

4. The vehicle was aware of your presence.

5. The vehicle was real.

Environmental Presence Scale Items

To what extent did you feel that. . . (1= not at all – 5

very strongly)

1. You were really in front of a pedestrian crossing.

2. The road signs and traffic lights were real.

3. You really crossed the pedestrian crossing.

4. The urban environment seemed like the real

world.

5. It could reach out and touch the objects in the ur-

ban environment.

Insertion of Real Agents Behaviors in CARLA Autonomous Driving Simulator

31