Expectation and Stock Returns: Evidence from Trademark

Applications

Jiaming Zhu

Beijing No.35 High School, Grade 12, IFY Engineering, Beijing, China

Keywords: Trademark, Expectation, Stock Return.

Abstract: This paper tests the hypothesis that companies’ trademark applications on an “intent-to-use” basis deliver

messages of new developing lines of products in the future. I collect data from USPTO and use fuzzy match

techniques to find the trademark applications for each publicly traded firm in the United States. I find stock

prices of the applicants are indistinguishable prior to the application but start to diverge in the month following

application. Moreover, I show evidence of a strong correlation between the trademark applications behaviours

and stock market index returns. My results imply that the applications of trademarks contain important

information of stock prices for firms.

1 INTRODUCTION

How does expectation impact a decision? Is

expectation biased? These two questions are of

general interests to economists in general., and I find

trademark application behaviours of public firms are,

to some extent, a good opportunity to address these

two questions.

Trademark is a recognizable sign, design, or

expression that identifies products of a particular

source from products of others. Therefore,

trademarksare important for product differentiation.

However, in contrast to our impression of trademark

applications, over half of them are filed on an “intent-

to-use” basis, which means to file an application,

there is no need to have any existing product in

production or sales. The U.S. Patent and Trademark

Office (USPTO)--the authority of trademark

application and registration– allows a maximum of 36

months before a final decision to register or abandon

the mark.

Therefore, an intention to apply for a product

mark suggests a company’s hope to develop new

lines of products. Before application, investors form

expectations of a company’s future growth rates.

After application, a company invests to research,

develop, and collect information to determine if they

will continue R&D on the product. This decision then

translates into a decision to register or abandon the

application. This divergence causes heterogeneous

shocks to investors of applying companies: positive

shock to investors of those registering applicants and

negative shocks to investors of abandoning

applicants. Do stock prices move accordingly?

If expectation is incorporated into a stock price,

then there is no difference between the two types of

companies before a trademark application, and

following the application, stock prices should move

in line with the type being revealed when uncertainty

is gradually resolved.

To answer the second question of expectation

bias, I first build an illustrative model which is

necessary because the impacts of expectation bias are

mixed with shocks to different types. The model

predicts that the average abnormal return to

trademark applicants will deviate from zero if the

expectation is not rationally formed. In particular,

negative abnormal returns on a high type implies

huge optimism and positive returns on low type

implies huge pessimism. My results suggest that there

is considerable optimistic expectation bias across

firms and over time on average, even causing

negative returns for registering applicants.

My research mainly contributes to three fields of

research. First, this paper is related to research in

behavioral finance such as Abarbenell and Bernard

(Abarbenell, Bernard, 1992) Amronin and Sharpe

(Amronin, Sharpe, 2013), Hirshleifer and Yu

(Hirshleifer, Yu, 2012), Greenwood and Shleifer

(2014), Gennaioli et al. (2015) and Barberis et al.

(2018) which find that investor expectations are

Zhu, J.

Expectation and Stock Returns: Evidence from Trademark Applications.

DOI: 10.5220/0011360400003440

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Big Data Economy and Digital Management (BDEDM 2022), pages 973-978

ISBN: 978-989-758-593-7

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

973

extrapolative. Barberis (Barberis 2003) provides a

good handbook of behavioral finance topics. Many of

them use survey data of investors, CFO/CEOs and

analysts

1

. However survey expectations can suffer

from measurement error problem. Greenwood and

Shleifer’s (Shleifer 2014) paper suggest survey

expectations of future returns are low in recessions

which seems controversial as surveyees may

misunderstand the survey questions. Instead of

studying the expectation itself, I study the ex post

responses to the expectation formed earlier when

information is gradually available to resolve

uncertainty. In particular, the ex post outcome is

binary and identifiable in my setting: a company

either registers or abandons the application. Most of

existing research relies on the argument that a rational

expectation predicts that the average stock returns are

zero even though the high type are faced with positive

shock and low type are faced with negative shocks.

This binary division of types via application outcome

lends researchers another lens to study the impacts of

expectation bias.

Second, my research is also related to stock return

reversals. In general, I find a negative 1-year return

predictability around trademark applications.

Jagadeesh (Jagadeesh 1990) and Lewellen (Lewellen

2001) are examples that show negative short-horizon

autocorrelation of returns. Explanations of

“reversal”/”momentum” are broadly divided into

overreaction and underreaction. My results point to

overreaction in explaining a 1-year reversal of stock

returns. The “overreaction”/“underreaction” can also

be rephrased as “optimism”/“pessimism”. The former

behaviour pair refers to investors’ reactions to any

news about the prospect of the stock. The latter

sentiment pair describes investors’ attitudes towards

uncertain futures. My study shows the second type;

when information is not enough to resolve

uncertainty, investors tend to overestimate future

growth rates, and stock prices start to diffuse when

uncertainty is resolved. It is worthwhile to emphasize

that the 1-year negative autocorrelation is augmented

when there are trademark application events. It

suggests that trademark application initiates an

important period of information release.

The last contribution of my research is enhancing

people’s understanding of trademarks. Compared to

patents, the value of trademarks are small and

ambiguous, and the innovation behind a trademark is

lower (Krasnikov, 2009, Schmoch, Gauch, 2009). It

1

Gennaioli et al. (2015) provides a good comparison

among them

is not surprising. Patents exclude rivals from using

the technology such that they are totally prohibited

from entry to the market. Trademarks, however,

mostly lead to horizontal differentiation of products

and add marginal value to a firm. Hsu et al. (2018)

used the similarities of trademark portfolios among

firms to study a firm’s intention to merge and the

resulting impacts on industry competition. My results

are supposed to draw the attention of researchers to

another important yet ignored dimension of

trademarks: the expectations of future growth.

In the sections to follow: section 1 describes the

trademark data set; Section 2 shows the sample

selection and summary statistics; Section 3 is a

simple model that illustrates the impact of

expectation bias on stock returns; Section 4 provides

empirical evidence for the model at both the

aggregate and firm levels; Section 5 concludes.

2 DATA DESCRIPTION

2.1 Trademarks

The USPTO is an agency mostly known for issuing

patents for inventions to inventors and businesses.

Another important, but often forgotten role, is that

they also issue trademark registration for product and

intellectual property identification. Trademarks are

important for product differentiation via a form of

recognizable sign, design, or expression that

identifies products of a particular source from those

of others

2

. Therefore, companies with profitable

products have an incentive to register a mark for their

product so that they can enjoy the exclusive benefits

of their product and identify against their rivals.

For the purpose of this research, I will only focus

on applications with two distinctive features: (1)

applications that signal new product lines and (2)

applications for products that have uncertain

prospects. The first feature leaves a task to filter out

trademarks that are not related to specific products or

are for advertising/marketing purposes. The previous

points to logos that can be used for any of a

company’s products; the latter case is advertising

slogan or redesign of the slogan. Even though

USPTO does not directly provide a classification of

product versus marketing, the datasets provided by

2

There are also service markers, but their percentage in

the dataset is small . I will only focus on those about

products.

BDEDM 2022 - The International Conference on Big Data Economy and Digital Management

974

USPTO

3

allow researchers to determine a product

mark from a marketing mark. Following Hsu et al.

(2017), this research relies mainly upon two sources

of information to determine if a trademark is related

to specific products: drawing code and identification

character. In general, the trademark should have a

moderate amount of textual content and the text of the

mark should be relatively novel. (See Appendix 1 for

details of the classification scheme.)

I am also interested in trademark applications

because they express companies’ intentions to invest.

In general, there are two legal bases of applications:

“intent-to-use” and “in-use”

4

. “Intent-to-use”

applications can be filed when there is no product, but

applicants must file a declaration stating that they

have a bona fide intent to use the mark in commerce.

To file under the use basis, the owner must submit a

declaration stating that, as of the filing date, the mark

is used in commerce. The first option has only been

available since November 1989. An applicant filing

based on intended use cannot obtain registration until

(a) the mark is actually used in commerce, (b) a

verified statement or declaration to that effect is filed,

and (c) a specimen of use is submitted. By default,

there is a 6-month window for the applicant to file a

Statement of Use (SOU). The applicant may request

up to five six-month extensions for filing the SOU,

making the effective deadline for establishing use up

to 36 months. If the owner fails to establish use, the

application is treated as abandoned. Furthermore,

unlike patents, the review of trademark applications is

simple: (1) procedural matters such as proper

identification of the products and (2) the applicant’s

mark is not merely descriptive or likely to cause

confusion with a preexisting applied-for or registered

mark. With these said, for “intent-to-use” applicants,

they play an active role in the process-the decision to

apply and the decision to exit. Therefore, behaviors

engaged in trademark applications imply much about

a company’s expectations of future growth and how

they adjust to new information after the application.

2.1.1 Example: Apple Inc

One good case study about trademarks is Apple Inc.,

the world famous technology company that designs,

develops, and sells consumer electronics, computer

software, and online services. Its website

5

, has an non-

exhaustive list of 286 active and registered trademarks

owned by Apple Inc., and I matched about 80 % of

3

https://www.uspto.gov/learning-and-

resources/electronic-data-products/trademark-case-files-

dataset-0

4

See Graham et al. (2013) for more details.

them by name with the data set from USPTO

6

.

Additionally, using USPTO’s trademark data set, I

found 973 applications made by Apple Inc. since

1977. 66.5% are for new products, 59.5% are filed on

the basis of “intent-to-use,” and 18.8% are abandoned.

In the pool of applications made by Apple Inc.,

there are strong examples to show the difference

between: (1) a marketing trademarks and production

trademarks; (2) an “intent-to-use” and “In-Use”

application; and (3) registered applications and

abandoned applications. In Appendix 2, I have a list

of sample trademark applications made by Apple Inc.

Except for those well know logos and brands, for

example iPhone 6 and iPod, there are also many

attempts on products that are eventually abandoned,

for example the “Premium Reseller” and “X-Ray”.

The case of applying for a trademark for the first iPod

in 2001 is a good example of “intent-to-use”. Though

the iPod was released in 2001, its price and Mac-only

compatibility caused sales to be relatively slow until

2004. The final registration of the trademark was in

April of 2004. So what concerns the applicant of

trademarks is not only product development out of an

idea or technology, but also sales and profits.

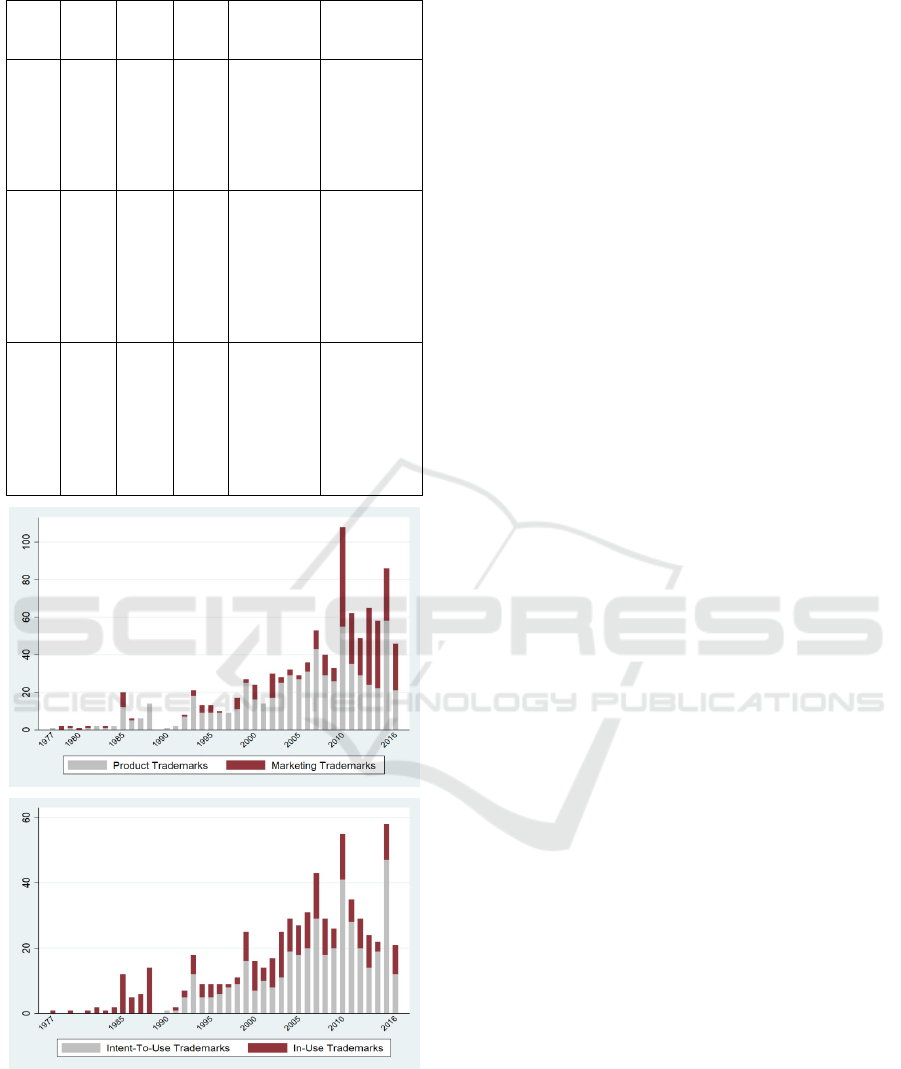

Apple Inc.’s history of trademark applications

(Appendix) is typical for public firms. First, in the

early stage of the company, they devote more effort to

the research and development of new products, and in

later stages they focus on marketing and advertising to

shape their corporate image. Second, when firms have

developed, they become more aggressive/encouraged

to develop new products and apply for ”intent-to-use”

trademarks to seize the opportunity for any potentially

profitable projects.

3 RESULT

3.1 Summary Statistics

Since I will use the sample of intent-to-use

applications among public firms, I want to have an

overview of their patterns. I compare the time series

of public firms’ trademark applications growth rate of

intent-to-use (ITU) applications with a set of

aggregate level variables. I conduct pairwise

comparisons in Figure 1 and also show the correlation

matrix in Table 1. Grow rates or returns are

5

https://www.apple.com/legal/intellectual-

property/trademark/appletmlist.html

6

The unmatched can result from little difference in

names.

Expectation and Stock Returns: Evidence from Trademark Applications

975

logarithmized and over 12-month period: growth(x)

=100*[ln(X

t

) - ln(X

t-12

)] where t is the month.

First, I compared it with the ITU growth rate of

all applicants (both public and private). They have

very similar patterns and a correlation coefficient of

0.8. The most stark

disparity is in the period of the “dot-com bubble”

between 1995-2000. The public companies are less

aggressive in filing applications than private

companies. Otherwise, the magnitudes and patterns

of the two time series are very similar. This suggests

that even though the matched sample of public

companies only contributes to 14% of the

applications, it is a representative sub-sample.

Second, I compared it with SP500 index total return,

and the two are highly correlated with coefficients of

0.6. Companies tend to file more trademarks in times

of bull market. I also check if the growth rate predicts

future SP500 return and find insignificant correlation.

Third, I compared it with the growth of in-use

applications in the same sample of public firms.

There are co-movements, but the growth of intent-to-

use is more volatile and has higher correlation with

the prior 12-month stock market performance.

Fourth, I wanted to check if a higher growth rate was

followed by lower probability of registration. There

is no evidence for this. However, registration rate is

associated with future performance.

This summary is a prelude of the empirical studies

to follow. It does not provide strong support to a story

of expectation bias and diffusion around trademark

applications. Therefore, I need more thoughtful

empirical design to disentangle the effects from these

other noises.

3.2 Correlation with Market Index

Return

For my empirical studies, I also used the SP500 index

total return, monthly stock return data from CRSP,

and returns to factors from Kenneth French’s Data

library

7

. Returns were value-weighted when there are

multiple stocks (permno) for one company (permco).

Also, consistent with most empirical asset pricing

research, I deleted stocks whose price is below five

dollars a share (for example, Jegadeesh and Titman

2001, Lou 2012) to address potential micro-structure

issues. Moreover, I used the logarithm of returns.

7

Kenneth French’s Data library.

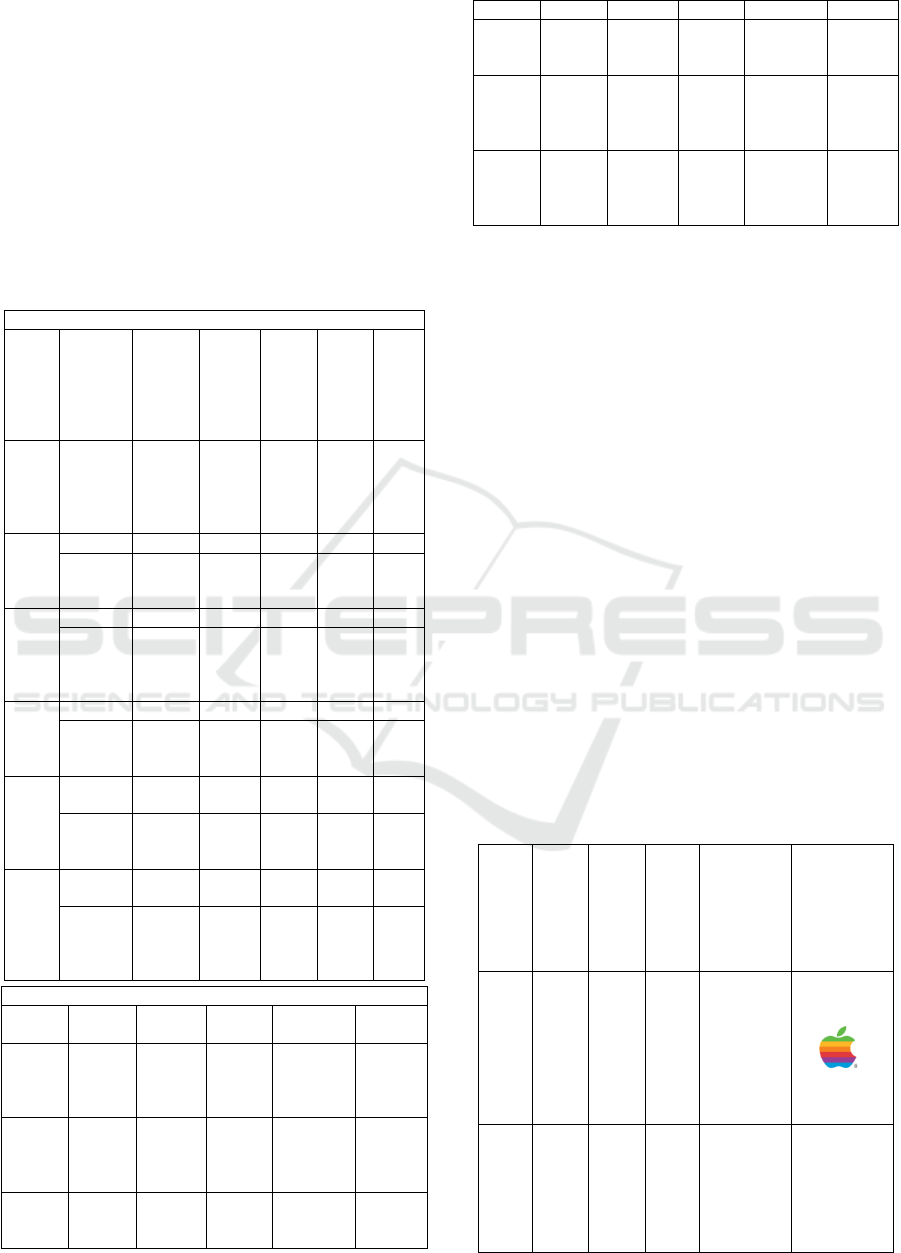

Figure 1: Public firms’ intent-to-use application growth and

other variables in the time series.

There are five variables in these figures: the

growth rate of intent-to-use (ITU) applications by

public firms; the growth rate of intent-to-use (ITU)

applications by all firms; the growth rate of in-use

(IU) applications by public firms; the rate of

registration of ITU applications by public firms; the

past 12-month SP500 index total returns. I compared

pairwise between the first and the other four variables

in four figures, and I plotted the data in quarterly

frequency–each point presents the quarter-end month

value. Rates and returns are in percentages.

4 CONCLUSION

A company filing trademark applications on an

"intended use" basis conveys a message of

developing a new product line. After an application,

the effect is gradually visible. This research

determined that an applicant's stock price was

indistinguishable prior to application, but

disagreements began to emerge within a month of the

application. In addition, the number of trademark

application filings is positively associated with the

market index returns. My findings support that

trademark applications contain valuable information

for stock pricing. To a certain extent, the effect of

trademark registration measures the innovation

degree of a company's new product. The difference

BDEDM 2022 - The International Conference on Big Data Economy and Digital Management

976

between a trademark and a patent is that the object

and content of their protection are different.

The findings in the paper also pave the way for

future explorations. I can construct the tradeable

portfolio holding companies that have recently filed

trademarks. I can check if they can generate

exceptional returns which cannot be explained by a

six-factor model. If the risk-adjusted returns are

negative, it can support the optimistic expectations

bias and may help explain short-term reversals in

equity returns.

Table 1: Correlation and Summary Statistics.

Panel A: Correlation Matrix

Growth

(ITU,P

ublic)

Growt

h

(ITU,

All)

Grow

th

(IU,P

ublic)

Reg.

%

Past

12m

Stoc

k

Ret.

Fut

ure

12m

Stoc

k

Ret.

Gro

wth

(ITU

,Pub

lic)

1

Gro

wth

(ITU

,All)

0.800* 1

(0.00)

Gro

wth

(IU,

Publ

ic)

0.552* 0.603* 1

(0.00) (0.00)

Regi

strati

on

%

0.039* -0.103 0.104 1

(0.71) (0.33) (0.32)

Past

12m

Stoc

k

Ret.

0.590* 0.595*

0.384

*

-

0.108

1

(0.00) (0.00) (0.00)

(0.30

)

Futu

re

12m

Stoc

k

Ret.

0.116 0.083 0.103

0.233

*

0.09

7

1

(0.27) (0.43) (0.33)

(0.02

)

(0.02

)

Panel B: Summary Statistics

Variab

le

Obs Mean Std.

Dev.

Min Max

Growt

h

(ITU,P

ublic)

92

2.4

1

13.

36

-28.50

25.8

9

Growt

h

(ITU,

All)

92

5.8

1

15.

06

-36.70

47.2

8

Growt

h

(IU,Pu

92

-

2.6

3

10.

21

-30.67

25.4

7

b

lic)

Regist

ration

%

96

58.

68

4.3

6

50.43

69.9

6

Past

12m

Stock

Ret.

96

6.7

9

17.

57

-50.55

38.2

3

Future

12m

Stock

Ret.

96

7.4

0

17.

48

-50.55

38.2

3

There are six variables in these figures: the growth

rate of intent-to-use (ITU) applications by public

firms; the growth rate of intent-to-use (ITU)

applications by all firms; the growth rate of in-use

(IU) applications by public firm; the rate of

registration of ITU applications by public firms; the

past 12-month SP500 index total return; and the

future 12-month SP500 index total return. The first

panel of their correlation coefficients and p-values

are shown in brackets (Significance level:* 95% ).

The second panel provides a summary of statistics of

the six variables. I only keep quarter-end month

values, resulting in a time series of quarterly

frequency for each variable. Rates and returns are in

percentages.

APPENDIX

The following table lists detailed information of five

typical trademark applications made by Apple Inc..

The information is extracted from USPTO case file

and USPTO trademark search system.

Table:Examples of Trademark Applications by Apple Inc.

S

e

ri

al

N

0.

T

yp

e

Le

gal

Ba

sis

F

il

in

g

D

at

e

Reg

. /

Aba

n.

Dat

e

Log

o /

Nam

e

7

3

1

2

0

4

4

4

M

ar

ke

ti

ng

In-

Us

e

2

5/

0

3/

1

9

7

7

29/

11/

197

7

8

6

5

0

1

8

Pr

od

uc

t

In-

Us

e

1

3/

0

1/

2

0

09/

08/

201

6

IPHONE 6

Expectation and Stock Returns: Evidence from Trademark Applications

977

9

9

1

5

7

5

9

8

2

8

7

1

Pr

od

uc

t

Int

ent

-

To

-

Us

e

1

8/

1

0/

2

0

0

1

27/

04/

200

4

IPOD

8

5

1

7

9

3

6

1

Pr

od

uc

t

Int

ent

-

To

-

Us

e

1

7/

1

1/

2

0

1

0

04/

05/

201

5

(Ab

n.)

PREMIUM

RESELLER

7

7

0

9

9

1

7

0

Pr

od

uc

t

Int

ent

-

To

-

Us

e

0

5/

0

2/

2

0

0

7

20/

11/

200

8

(Ab

n.)

XRAY

Figure 2: Apple Inc.’s Yearly Number of Trademark

Applications By Type and Legal Basis.

REFERENCES

Amromin, G. and Sharpe, S.A., 2013. From the horse’s

mouth: Economic conditions and investor expectations

of risk and return. Management Science, 60(4), pp.845-

866.

Argente, D., Lee, M. and Moreira, S., 2018. How do Firms

Grow? The Life Cycle of Products Matters.

Barberis, N., Greenwood, R., Jin, L. and Shleifer, A.,

2018. Extrapolation and bubbles.

Bloom, N. and Van Reenen, J., 2002. Patents, real options

and firm performance. The Economic Journal,

112(478), pp.C97-C116.

Fama, E.F. and French, K.R., 1988. Permanent and

temporary components of stock prices. Journal of

political Economy, 96(2), pp.246-273.

Faurel, L., Li, Q., Shanthikumar, D. and Teoh, S.H., 2015.

CEO incentives and product development innovation:

Insights from trademarks.

Gennaioli, N., Ma, Y. and Shleifer, A., 2016. Expectations

and investment. NBER Macroeconomics Annual,

30(1), pp.379-431.

Greenwood, R. and Shleifer, A., 2014. Expectations of

returns and expected returns. The Review of Financial

Studies, 27(3), pp.714-746.

Hirshleifer, D., Li, J. and Yu, J., 2015. Asset pricing in

production economies with extrapolative expectations.

Journal of Monetary Economics, 76, pp.87-106.

Hsu, P.H., Li, K., Liu, Y. and Wu, H., 2018. Product Market

dynamics and mergers and acquisitions: Insights from

the USPTO trademark data.

Kogan, L., Papanikolaou, D., Seru, A. and Stoffman, N.,

2017. Technological innovation, resource allocation,

and growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics,

132(2), pp.665-712.

Krasnikov, A., Mishra, S. and Orozco, D., 2009. Evaluating

the financial impact of branding using trademarks: a

framework and empirical evidence. Journal of

Marketing, 73(6), pp.154-166.

Lewellen, J., 2001. Temporary movements in stock prices.

Millot, V., 2009. Trademarks as an indicator of product and

marketing innovations.

Sandner, P., 2009. The market value of R&D, patents, and

trademarks. In The Valuation of Intangible Assets (pp.

35-72). Gabler.

Schmoch, U. and Gauch, S., 2009. Service marks as

indicators for innovation in knowledge-based services.

Research Evaluation, 18(4), pp.323-335.

BDEDM 2022 - The International Conference on Big Data Economy and Digital Management

978