Maturity Model for Assessment of Personalization of

Higher Education

Mariia Rizun

a

and Małgorzata Pańkowska

b

Department of Informatics, University of Economics in Katowice, Katowice, Poland

Keywords: Maturity Model, Higher Education, Personalization of Education, Maturity Level.

Abstract: The paper presents the Education Personalization Maturity Model, developed to provide higher education

institutions with a tool for assessment of the level of their personalized approach to their students. These days

students tend to be much more engaged in the education process; they want their preferences to be considered

in not only in the learning process but in all aspects connected with educational institutions. The presented

model covers four major key process areas of practices at higher education institutions: students’ online

platform/website, courses and fields of study, research activity, and other extracurricular activities. The

Education Personalization Maturity Model is used to assess the personalization of 51 higher education

institutions in 25 countries. The results of this assessment are presented and analyzed in the paper.

1 INTRODUCTION

There is no doubt that higher education worldwide

has undergone significant changes not only within the

last century but even within the last decade.

Governments have been changing their educational

policies, higher education institutions (HEIs) have

been adapting to these novelties as well as

introducing their internal regulations – to stay

competitive and attractive for students.

Moreover, the attitude of students towards

education has changed. They are now perceived as

customers and active players in establishing their

learning path (Orîndaru, 2015). These days, when

talking about the quality of higher education, we talk

about a significantly increasing engagement of

students. Such engagement is considered a measure

of the quality of an educational institution: students

of a good institution are supposed to be actively

involved in educationally purposeful activities

(Quaye & Harper, 2014). It is seen as the premise of

students’ happiness. Researchers state that

guaranteeing students’ happiness as a result of their

development is much more crucial than just satisfying

students’ needs as consumers. Students who are

“happy” are more content with their engagement in

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9646-7638

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8660-606X

educational experiences, while those who are just

“satisfied” are more concerned with how education

services were delivered rather than in their

involvement with the process (Dean & Gibbs, 2015).

One of the ways to make students happier about

their educational path is to provide them with a

personalized approach of their HEIs towards their

preferences and aspirations. Developing personalized

education for students means, among others: allowing

them to tailor their study program as they desire (at

least to some extent) (Rollande & Grundspenkis,

2016); providing them with tutors or mentors who

help students define their educational and

professional path (Rollande, 2015); compromising

with students and adapting study plans to their

preferences (as much as it is possible) so that students

could combine studies with work or other important

activities (Grundspenkis, 2010); increasing the

number of workshops and other practical activities to

make students familiar with the business environment

(Zhu, 2016); motivating them to be curious, to

conduct research; developing good infrastructure

with all necessary facilities (e.g., sports, computers,

internet, library, etc.) (Kabak & Dagdeviren, 2014),

and many others.

When students study, participate in research

projects, take part in internships and exchange

Rizun, M. and Pa

´

nkowska, M.

Maturity Model for Assessment of Personalization of Higher Education.

DOI: 10.5220/0011537900003335

In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2022) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 43-53

ISBN: 978-989-758-614-9; ISSN: 2184-3228

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

43

programs, realize projects, or participate in any other

activities offered by their educational institutions,

they form some kind of a portfolio of all their

experience, knowledge, skills, and abilities. In other

words, it can be called a profile or, specifically, a

student’s Individual Higher Education Profile (also –

Individual Profile). This Individual Profile of a

student is most effectively formed with the

personalized approach of educational institutions

towards their students when HEIs provide students

with the elements of personalization discussed in the

previous paragraph (and many more). To make sure

the students are content with their educational path

realization, HEIs need to be able to answer such

questions as: what are the first steps towards

education personalization development; what rights

and privileges the students may have, and in what

activities there should be restrictions; how to evaluate

whether the approach towards students is

personalized, and to what extent; and many more.

The objective of this paper is to present a tool for

assessment of the level of personalization of

education at higher education institutions, developed

by the authors, which is the Education

Personalization Maturity Model (EPMM).

1.1 Maturity Models in HEIs

To examine the maturity models for educational

institutions, developed by researcher in the last

decade, the authors conducted the Systematic

Literature Review (SLR). In the process of selection

by title, abstract and paper content (in accordance

with the PRISMA guidelines

3

), the authors received

43 papers eligible for further review. In these works,

the authors revealed 13 maturity models created for

higher education institutions (Table 1). These models

are dedicated to the maturity of e-learning,

Information and Communication Technology (ICT),

planning and assessment of learning processes, and

some other processes that run at higher education

institutions.

Due to the fact that the literature review did not

reveal any maturity model dedicated to education

personalization or student’s Individual Profile

development, the authors see a research gap which

may be filled with the suggested EPMM model,

presented further in this paper.

3

“Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and

Meta-Analyses”. https://prisma-statement.org. [Accessed:

20.08.2022.

Table 1: Maturity models for HEIs: literature review

results.

Author(s) Maturity model

E-learnin

g

maturit

y

(Nsamba, 2019)

Maturity Assessment

Framework for Open

Distance E-Learning

(MAFODeL)

(Marshall & Mitchell,

2004

)

,

(

Marshall, 2010

)

E-Learning Maturity Model

(

eMM

)

(Penafiel et al., 2017)

Contribution to the eMM

with the inclusion of a new

Key Process Area –

Accessibilit

y

(Hong & Xinyi, 2019)

E-learning Process Capability

Maturity Model (EPCMM)

ICT maturit

y

(Durek, Kadoic, &

Begicevic Redep, 2018)

Digital Maturity Framework

for Higher Education

Institutions

(

DMFHEI

)

(Aliyu et al., 2020)

Holistic Cybersecurity

Maturity Assessment

Framework

(

HCYMAF

)

L

earning process planning and assessment maturity

(Thong, Yusmadi, Rusli,

& Nor Hayati, 2012),

(Thong, Jusoh, Abdullah,

& Alwi, 2013

)

Curriculum Design Maturity

Model (CDMM)

(Reçi & Bollin, 2017),

(

Reçi & Bollin, 2019

)

Teaching Maturity Model

(

TeaM

)

(Enke, Glass, &

Metternich, 2017),

(

Enke et al., 2017

)

Maturity Model for Learning

Factories

Other

p

rocesses maturit

y

(Carvalho, Pereira, &

Rocha, 2019

)

Higher Education Institutions

Maturit

y

Model

(

HEIMM

)

(Secundo, Elena-Perez,

Martinaitis, & Leitner,

2015

)

Intellectual Capital Maturity

Model (ICMM) for HEIs

(Matkovic, Pavlicevic, &

Tumbas, 2017)

Business Process Modeling

Maturity and Adoption

Model for HEIs

(Boughzala & de Vreede,

2015

)

Collaboration Maturity

Model

(

Col-MM

)

The structure of the paper is as follows: Section 2

contains the methodology of the EPMM

development; in Section 3 structure of the EPMM is

presented; in Section 4, the authors briefly introduce

the results of verification of the developed Model at

51 HEIs; in Discussion the authors conclude on the

obtained results of EPMM verification and

distinguish the contribution of this work, its

limitations, and potential further research.

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

44

2 EDUCATION

PERSONALIZATION

MATURITY MODEL

DEVELOPMENT

METHODOLOGY

2.1 Design Decisions when Developing

the Education Personalization

Maturity Model

The section presents the methodology of building the

Education Personalization Maturity Model developed

by the authors. The primary objective of the EPMM

Model development is to identify the practices related

to the personalization of education at HEIs and to

create the methodology of assessment of the quality

of these practices’ realization.

In 2011, (Mettler, 2011) suggested a framework

for maturity model design process, which consists of

five iterative steps: identify need or new opportunity,

define scope, design model, evaluate design, and

reflect evolution. The authors used this methodology

when making decisions for the EPMM Model (Rizun,

2021).

At the stage “Identify need or new opportunity”,

the authors see the EPMM Model as the “emerging”

and “new” one – because no maturity model for

personalization of higher education has been

developed so far. The “Define scope” decisions are

supposed to set the outer boundaries for the EPMM

Model application and use (de Bruin et al., 2005). The

authors’ choices are: “specific issue” (applied only for

HEIs), “inter-organizational” (covers internal

processes of HEIs and their cooperation with other

organizations), and “both” the Management- and

Technology-oriented staff of HEIs. In the “Design

model” activity, the EPMM Model is characterized as

follows: a “process-oriented” and “multi-

dimensional” (focuses on several objectives) model,

where the design process is a “combination” of theory

(e.g., literature review) and practice (the experts’

knowledge). The design product of the EPMM Model

is a “combination” of textual description and software

instantiation. The EPMM Model is supposed to be

implemented by HEIs with no third parties engaged,

so the application method is “self-assessment”.

Finally, the “combination” of management, staff, and

business partners, as respondents of the EPMM

Model, was selected. The subject of evaluation in the

“Evaluate design” stage is “design product”. The

evaluation and verification of the EPMM Model are

to be conducted before it is implemented, so the

option of “ex-ante” evaluation is selected.

Additionally, the evaluation is to be performed with

the “naturalistic” method, i.e., it should be based on

the experience and reflection of real users (Carvalho

et al., 2019). In the “Reflect evolution” activity, the

authors have selected “continuous” evolution. The

authors also believe that the modifications in the

EPMM Model can be implemented by its users,

which leads to the “external/open” structure of

change.

2.2 Information Basis of the EPMM

Model Development

In the process of developing the Education

Personalization Maturity Model, the authors used the

following primary sources of information:

1. Literature on maturity models in general and

those developed for educational institutions. It

provided the authors with knowledge on how the

models should be constructed and what are the

obligatory and optional constructs of a maturity

model.

2. Design decisions developed in (Mettler,

2011), discussed above. They allowed the authors to

define the issues of particular importance in the

process of maturity model design and to organize and

document this process.

3. Resolutions, ordinances, regulations, and

other official documents, issued by the authorities of

the University of Economics in Katowice (UEKat),

which is the authors’ affiliation. On the basis of these

documents, the authors built a picture of UEKat

policy as for personalized approach toward students.

Good practices were analyzed and used in the EPMM

Model as examples of high levels of personalization

maturity; practices that might require improvement

were put to the lower levels of maturity.

4. Opinions of students of a few Polish HEIs,

obtained through a questionnaire survey.

Since the primary focus of the paper is the final

version of the EPMM Model, not each step of its

development, the detailed questionnaire results are

not presented. As stated above, they found reflection

in the EPMM Model structure.

3 EDUCATION

PERSONALIZATION

MATURITY MODEL

STRUCTURE

Researchers distinguish three major components that

Maturity Model for Assessment of Personalization of Higher Education

45

define a maturity model (Nelson et al., 2014):

content, its quality, and the indicators of maturity

status. The content is formed by practices, processes,

and categories. Under the term “practices”, the

authors understand the policies and activities of a HEI

on specific issues, which are the focus of a particular

maturity model or framework. In the case of the

EPMM, the focus is on the practices connected with

personalization development. Practices of a similar

kind could be synthesized into broader process

categories or key process areas (KPAs).

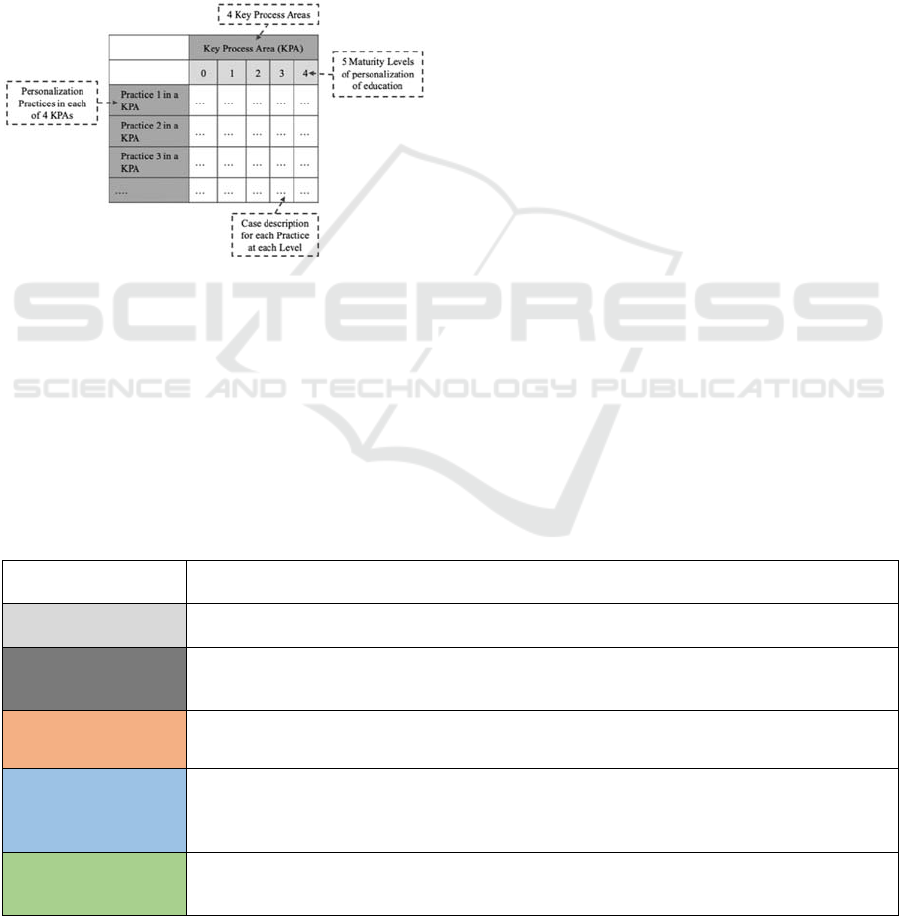

The basic structure of the EPMM is presented in

Figure 1.

Source: own

Figure 1: Basic structure of the EPMM Model.

The authors distinguish 34 practices connected

with the personalization of education. That is, with

the realization of these practices, personalization of

students’ education at HEIs is formed and/or

improved. These 34 practices are grouped into four

KPAs. Each of the practices within each of the four

KPAs contains descriptions of five cases, each

referring to a certain maturity level (from 0 to 4, as

shown in Table 2). Each case is a situation suggested

to occur at the analyzed HEI; the higher the level, the

more expanded the description of the case is, i.e., the

more advanced personalization of education is

observed at the selected HEI.

3.1 Levels of Maturity

As stated in the literature, organizations may be

characterized by levels of maturity or by dimensions

(Marshall, 2010). In dimensions, a five-point

adequacy scale is used to evaluate the quality of

performed practices (Anicic & Divjak, 2020). The

scale of maturity levels starts with level 1, which

characterizes the maturity of an organization as the

one that exists at an initial level. It is supposed that at

this level, some practices expected to be realized, are

present, but there is no system, and the realization is

somewhat chaotic and poorly controlled.

However, the authors consider that it might be

reasonable to define a level of maturity characterized

as zero maturity – for an organization that has not

made a single step toward developing a particular

practice analyzed. The authors’ suggestion is to name

this level as “not assessed (0)” – referring to the first

of the values of maturity assessment criteria (not

assessed, initial, partially adequate, largely adequate,

fully adequate). Therefore, the authors suggest

modifying a more standard scale of maturity levels,

introducing a “zero” or “nor assessed” level of

maturity of personalization of education at higher

education institutions.

The other amendment to the maturity levels,

suggested by the authors, is merging the levels

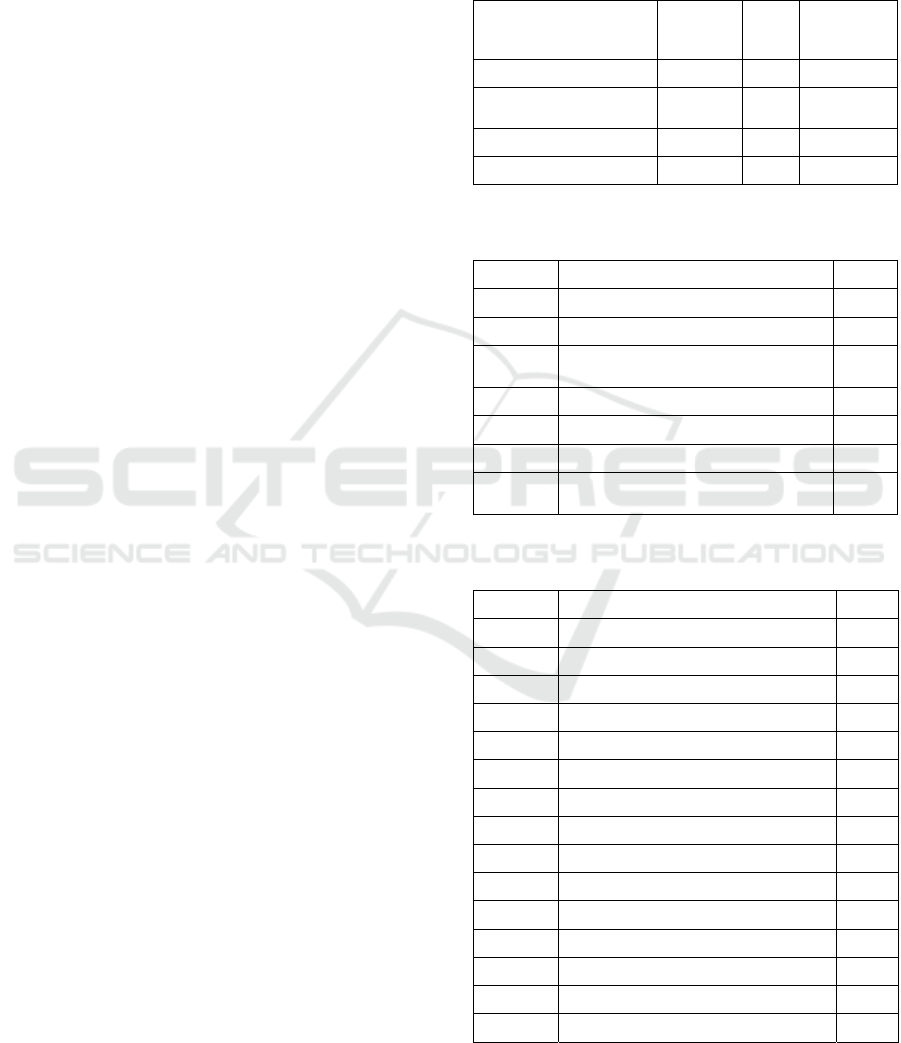

Table 2: Maturity levels in the Education Personalization Maturity Model.

Levels of

p

ersonalization maturit

y

Description of the levels

Not assessed (0) There is no evidence of personalization of education at the selected HEI.

Initial / ad hoc (1)

Few processes connected with personalization are defined, but much depends on individual effort

and will of a participant in the processes involved. Realization of practices is not systematic, and

there is no centralized control over them.

Repeatable (2)

Basic management is established. Some processes are consistent, but there is still no discipline

for all the processes and sub-processes that might contribute to personalization development.

Defined &

managed (3)

Development of personalization is standard, consistent, and predictable. Practices are

documented and integrated into standard processes. However, the selected HEI lacks suggestions

for potential improvement of the practices connected with personalization. Realization of

p

ractices might not be connected with the external environment.

Optimizing (4)

The process of personalization is being constantly improved. Personalization practices are

formally defined. All practices are controlled and documented. External environment of the

selected HEI is activel

y

en

g

a

g

ed in

p

ersonalization develo

p

ment.

Source: own, based on (Anicic & Divjak, 2020)

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

46

“defined” and “managed” into one. The authors give

it a simple name “defined and managed”. It is

suggested that at this level of personalization, all the

processes, sub-processes, and different activities, are

already clearly defined and precisely controlled, yet

the selected educational institution is supposed to

remain at the same stage of personalization

development, and there is no improvement observed.

Table 2 contains the authors’ version of the five

levels of maturity applied in the EPMM.

3.2 Key Process Areas and Practices

Researchers distinguish three major components that

define a maturity model (Nelson et al., 2014): content,

its quality, and the indicators of maturity status. The

content is formed by practices, processes, and

categories. Under the term “practices”, the authors

understand the policies and activities of a HEI on

specific issues, which are the focus of a particular

maturity model or framework. In the case of the

EPMM Model, the focus is on the practices connected

with personalization development. Practices of a

similar kind could be synthesized into broader

process categories or key process areas.

The authors distinguished 34 practices connected

with the personalization of education. That is, with

the realization of these practices, personalization of

students’ education at HEIs is formed and/or

improved. These 34 practices are grouped into four

key process areas. Each of the practices within each

of the four KPAs contains descriptions of five cases,

each referring to a certain level of maturity (from 0 to

4, as shown in Table 2). Each case is a situation

suggested to occur at the analyzed HEI; the higher the

level, the more expanded the description of the case

is, i.e., the more advanced personalization of

education is observed at the selected HEI.

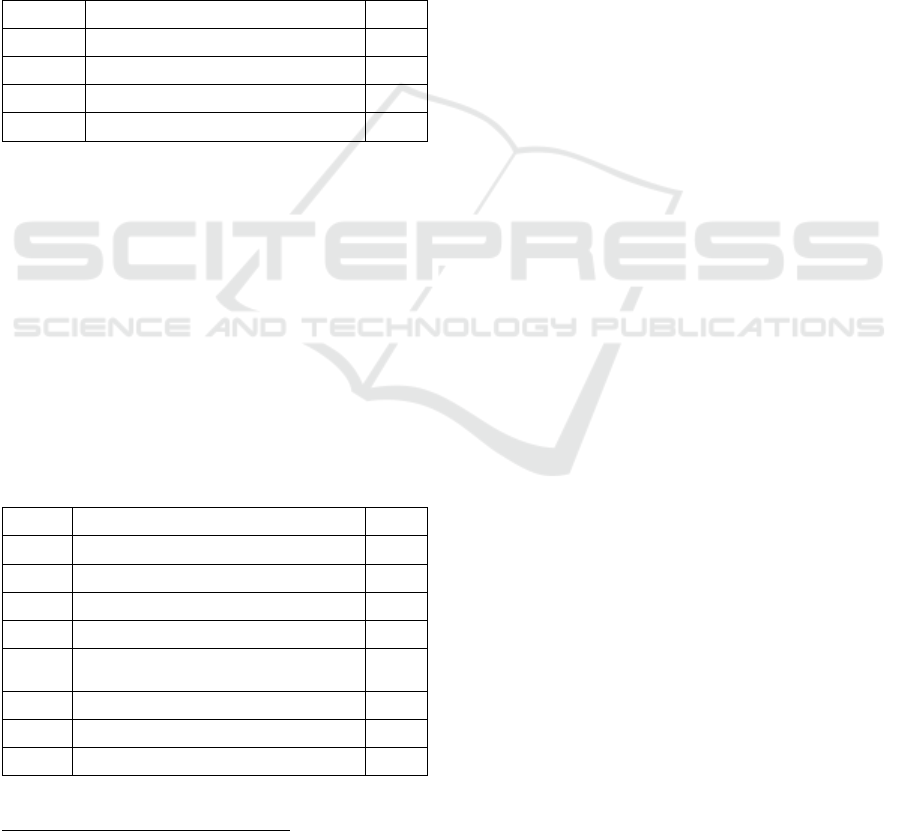

A list of the defined key process areas is presented

in Table 3. In Tables 4-7, practices for each KPA are

enumerated. In addition, these tables include ratings

or, better say, weights of each of the KPAs and

practices. The higher the weight, the more important

a certain KPA or practice is supposed to be, and the

greater its role is in the development of

personalization of education at HEIs.

KPA1 – “Students’ Platform” (SPL), contains

seven practices (Table 4). Under the Students’

Platform, the authors understand a separate website,

or a part of HEI’s website, which is dedicated only to

students’ needs like providing them with information

about fields of study and specializations, elective and

obligatory courses, practices, and internships, exams

and grades, conferences, social events, changes in

schedule or any other organizational issues;

submitting documents or registration forms; and other

issues that might be necessary for students of a

particular educational institution.

Table 3: Key process areas in the EPMM Model.

Key process area Acronym Rating

Practices

inside the

KPA

Students’ Platform

SPL 0,400 SPL1 – 7

Courses and Fields of

Study

CFS 0,300 CFS 1 – 15

Research Activity

RSA 0,100 RSA 1 – 4

Extracurricular Activities

EXA 0,200 EXA 1 – 9

Source: own

Table 4: Students Platform KPA: practices.

Acronym Practice statement Rating

SPL1 Students’ platform availability 0,250

SPL2 Course schedule available online 0,214

SPL3

Schedule of exams and other

evaluation works available online

0,143

SPL4 Grades available online 0,179

SPL5 Course materials availability online 0,036

SPL6 Registration forms availability online 0,107

SPL7

Students’ platform in a mobile

a

pp

lication version

0,071

Source: own

Table 5: Courses and Fields of Study KPA: practices.

Acronym Practice statement Rating

CFS1 Course grades transfer 0,125

CFS2 Changing the field of study 0,117

CFS3 Double diploma programs 0,092

CFS4 Exchange programs courses 0,075

CFS5 Course transfer in exchange programs 0,100

CFS6 Individual study plan 0,033

CFS7 E-learning 2.0 (informal) 0,058

CFS8 E-learning organization 0,067

CFS9 Evaluation works 0,083

CFS10 Course teachers 0,042

CFS11 Elective courses content 0,017

CFS12 Elective courses number 0,008

CFS13 Study plan content 0,025

CFS14 Students’ opinions 0,050

CFS15 Course schedule flexibility 0,108

Source: own

Maturity Model for Assessment of Personalization of Higher Education

47

KPA2 – “Courses and Fields of Study” (CFS),

contains 15 practices (Table 5), being the largest key

process area in the model. This is the KPA dedicated

to the issues of selecting courses, transferring

between specializations and fields of study or

between institutions, expressing preferences and

opinions on academic teachers and their teaching

methods, learning online, and others.

KPA3 – “Research Activity” (RSA), has only four

practices in it (Table 6). These practices consider

theses of bachelor’s and master's levels, students’

participation in scientific conferences, membership in

scientific organizations, and the overall research

activity of students.

Table 6: Research Activity KPA: practices.

Acronym Practice statement Rating

RSA1 Scientific tutorship 0,200

RSA2 Students’ scientific organizations

4

0,100

RSA3 Scientific conferences 0,300

RSA4 Bachelor’s / master’s thesis 0,400

Source: own

The last key process area (KPA4) –

“Extracurricular Activities” (EXA), includes eight

practices (Table 7). It covers, among others: students’

personal development, engagement in various

activities and events, providing students with access

to the internet and information databases, and

integration of students from exchange programs.

As stated above, all practices contain description

of cases for five maturity levels (0-4). Since it is not

possible to fit the tables with cases for all practices

into the paper, the authors chose to provide examples

of case descriptions, one per each key process area.

Table 7: Extracurricular Activities KPA: practices.

Acronym Practice statement Rating

EXA1 Personal development 0,222

EXA2 Students' organizations (non-scientific) 0,056

EXA3 Exchange students’ engagement 0,083

EXA4 Infrastructure 0,194

EXA5

Access to databases and electronic

resources

0,167

EXA6 Students’ decision-making 0,139

EXA7 Practices and internships 0,111

EXA8 Volunteering 0,028

Source: own

4

Scientific circles, research groups, research seminars,

research laboratories, etc.

Practice SPL1 (Students’ platform availability),

level 0 (Not assessed): “There is no platform or

website with information for students at the HEI”.

Practice CFS9 (Evaluation works), level 1

(Initial): “The HEI sets crediting formats for all

courses, and they cannot be changed on students'

request. The information is given in the official course

description”.

Practice RSA1 (Scientific tutorship), level 2

(Repeatable): “Students can apply for additional

scientific tuition only when they begin working on

bachelor's or master's thesis. Students' grades are not

taken into consideration. The HEI appoints the tutor”.

And finally, practice EXA5 (Access to databases

and electronic resources), level 4 (Optimizing): “The

HEI provides students with access to most (or all) of

the largest databases or other electronic resources.

Access is also possible from students’ private

computers (e.g., using VPN connection or a special

account)”.

Procedure of verification of the EPMM model

with all the practices and cases, which was conducted

at 51 higher education institutions, is discussed

further.

4 EDUCATION

PERSONALIZATION

MATURITY MODEL

VERIFICATION

Verification of the Education Personalization

Maturity Model, developed by the authors, was

conducted to assess the maturity of education

personalization at higher education institutions in

Poland and abroad. This assessment was conducted

with the help of a questionnaire that was distributed

among colleagues from different HEIs worldwide.

The sampling for this survey is a non-random

convenience sampling since the respondents were

selected based on their experience, their places of

work, as well as on the convenience of reaching them

out, and their willingness to participate in the survey.

As a result of the survey, the authors obtained 51

responses, i.e., 51 higher education institutions were

assessed using the Education Personalization

Maturity Model (I = 51). These 51 institutions belong

to 25 countries (C = 25) in Europe (68%), Asia (16%),

South America (12%), and Africa (4%). The authors

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

48

have applied Alpha-3 codes for countries, and further,

these codes are used to encode educational

institutions from particular countries.

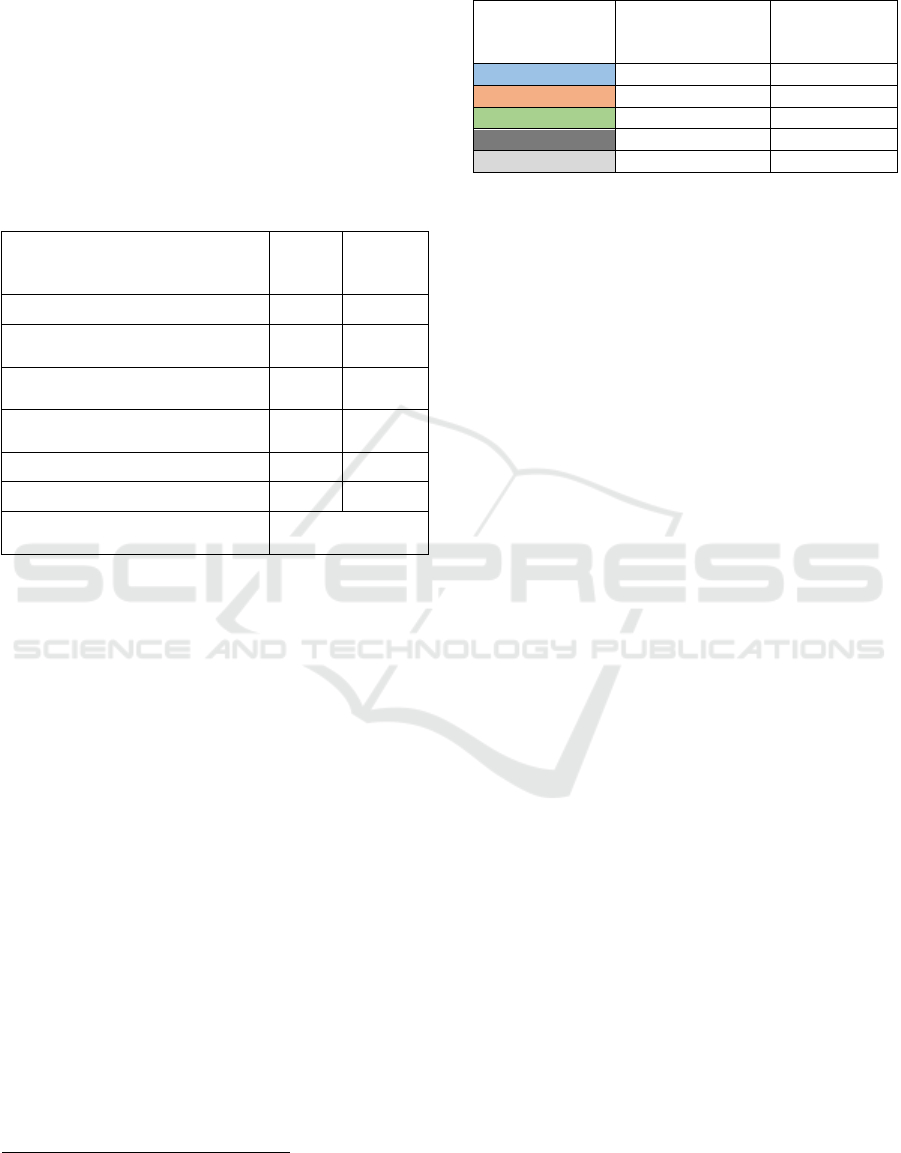

Table 8 provides information about the positions

the respondents occupy at their institutions. The

question about the position was a multiple-choice

one, so there was a possibility for a respondent to

claim to be, for instance, both an academic teacher

and a member of university authorities.

Table 8: Distribution of respondents’ positions at their HEIs

(I = 51).

Positions

Number

of

answers

% of total

number

of HEIs

Academic Teacher 33 64,71%

Academic Teacher, Research

Worke

r

9 17,65%

Academic Teacher, University

Authorities Membe

r

3 5,88%

Academic Teacher, Administrative

Staff Membe

r

2 3,92%

Administrative Staff Member 2 3,92%

University Authorities Member 2 3,92%

Total number of answers = number

of HEIs

51

4.1 Higher Education Institutions

Assessment Results

To assess the maturity of individualization of a HEI,

the respondents had to select one of the five cases

(referring to five maturity levels) for each of the

practices within each of the key process areas.

All the answers from the Google Forms

questionnaire were gathered in Google Sheets, where

the authors then manually connected all the answer

options with the corresponding number of maturity

level (from 0 to 4). Thus, the personalization maturity

levels for each practice within the four KPAs

appeared. In the next step, maturity levels were

calculated for each key process area – by calculating

the weighted average with the help of the ratings of

practices (presented in Tables 4-7). Further, the

ratings of the KPAs (presented in Table 3) were

applied in the weighted average to calculate the final

personalization maturity levels for the 51 HEIs. The

results of the described calculations are presented in

Table 10. The aggregated statistics for 51 higher

education institutions are given in Table 9.

5

https://www.coursera.org

6

https://www.udemy.com

Table 9: Personalization maturity assessment: aggregated

results (I=51).

Level of

personalization

maturit

y

Number of HEIs

% of total

number

of HEIs

3 27 52,94%

2 18 35,29%

4 3 5,88%

1 3 5,88%

0 0 0,00%

Source: own

These final results of the personalization maturity

assessment allow the authors to distinguish some

HEIs that had developed personalization for their

students and had put it on a high level, and, on the

contrary – that are still at the beginning of

personalization development and have a lot of good

practices to introduce.

Of the 51 HEIs assessed, most (27; 52,94%)

obtained the level of maturity 3 “Defined and

managed”, which means that they had developed

most of the personalization practices considered in

the EPMM, but still have options for improvement.

The fourth place is taken by three HEIs with level 1

“Initial / ad hoc” (5,88%). These institutions are

characterized as those having only a few

personalization practices realized, without any

common system, and supported mainly by individual

efforts of academic and administrative staff.

Within the “Students’ Platform” KPA, most

institutions (24; 47,06%) have the same high level of

personalization (level 4 or close to it) related to the

platform for students. For all institutions, the weakest

point seems to be the mobile application with all

necessary information for students, with frequent

updates and notifications. One more issue, which

appears to be insufficiently developed, is the schedule

of courses and exams available and updated online

(when students do not have to download, for instance,

a PDF file from a website and compare it with

previous versions to reveal changes).

Levels of practices development within the

“Courses and Fields of Study” KPA vary rather

significantly. Most common problems in this KPA,

for all institutions, are: 1) informal e-learning – taking

online courses on platforms like Coursera

5

, Udemy

6

,

Edx

7

, Mooc

8

etc., is not forbidden by HEIs, but it is

not (or poorly) motivated, supported, and rewarded;

2) internal e-learning – HEIs either do not offer any

courses provided online, or have very few of them,

probably with low possibility to replace traditional

7

https://www.edx.org

8

https://www.mooc.org

Maturity Model for Assessment of Personalization of Higher Education

49

courses with their online version; 3) choosing

teachers – students do not have any influence on the

process of assigning teachers to courses, or, probably,

they can choose teachers for very few courses (like

courses that are additionally selected); 4) number of

elective courses – from 0% to only 50% of courses

students are offered within their study programs can

be selected by students themselves on the basis of

their preferences, and the list to choose from is quite

small; the rest are set by HEIs authorities; 5) course

schedule flexibility – student have zero to low

influence of the schedule of courses they take; they

cannot apply for changes to be able to combine

education with work or other activities efficiently.

The most well-developed practices in this KPA are:

1) exchange programs – as host institutions in

programs like Erasmus, HEIs offer a lot of courses

and do not forbid to take more courses than it is set

by the program if students are interested in getting

more knowledge and skills; 2) variety of elective

courses – such courses can belong to different

specialization and fields of study at the selected HEI,

they can be taught in foreign languages, and their

number is not limited by the HEI; 3) consideration of

students’ opinions – courses evaluation is conducted

every semester, students’ opinions about teachers,

content, learning methods, etc., are gathered;

information is given to Heads of Departments and to

teachers to conduct improvements. Polish HEIs

mostly take levels between 2 and 3 in this KPA.

As for the “Research Activity” KPA, 49,02% of

assessed HEIs take level 3 (“Defined and managed”)

for the development of practices connected with

supporting their students’ research activity. For

50,98% of the educational institutions, the practice of

scientific tutorship for students is not developed

(levels 0 and 1). This means that either there is no

tutorship at all, or tutors can be appointed only at the

master’s degree, only to students with a high average

grade, and, perhaps, only by HEI authorities with no

option for students to make their own choice. One

more weak point in the personalization of research

activity is the practice of running scientific

organizations. 19,61% of institutions have this

practice at level 0 (“Not assessed”). These HEIs do

not run any students’ scientific organization (e.g.,

scientific circles, laboratories, etc.). Two other

practices remaining in this KPA are well-developed

at 68,63% of educational institutions and poorly

developed at 31,37%. Therefore, 68,63% of HEIs

regularly organize scientific conferences for their

students to participate in, with many urgent topics

covered; HEIs may finance the participation of their

students in conferences organized by other

Table 10: Personalization maturity assessment results.

HEI

KPA1 -

SPL

KPA2 -

CFS

KPA3 -

RSA

KPA4 -

EXA

Level of the

HEI

ALB-1 3 2 2 3 3

ALB-2 3 1 2 2 2

BRA-1 3 2 4 4 3

BGR-1 1 2 2 3 2

CZE-1 4 2 3 4 2

DEU-1 3 3 3 3 3

EGY-1 3 1 2 3 3

FRA-1 4 2 0 2 2

GRC-1 3 2 3 3 3

GRC-2 3 1 1 2 3

HUN-1 3 2 3 3 2

HUN-2 3 2 2 3 3

IRL-1 3 2 1 4 3

IRL-2 3 2 2 3 3

ITA-1 3 2 0 2 3

KAZ-1 3 2 3 3 2

OMN-1 4 3 2 3 3

OMN-2 4 1 1 2 3

PRY-1 2 1 1 2 1

POL-1 3 1 3 3 2

POL-2 4 3 4 3 2

POL-3 2 2 3 3 2

POL-4 4 3 3 3 3

POL-5 4 2 2 3 3

POL-6 1 1 1 1 1

POL-7 2 1 3 2 2

POL-8 3 2 3 3 3

POL-9 4 3 4 4 4

POL-10 4 3 3 4 4

POL-11 4 3 3 4 4

POL-12 2 2 3 4 2

POL-13 2 2 2 2 2

POL-14 3 3 4 4 3

PRT-1 3 2 1 3 2

PRT-2 4 2 4 3 3

ROU-1 4 3 3 3 3

ROU-2 4 3 4 3 3

RUS-1

3 3 3 3 3

RUS-2

3 3 3 3 3

SV

K

-1

2 1 1 1 1

SVN-1

3 2 2 1 2

ESP-1

3 2 1 3 2

ESP-2

4 1 2 3 3

ESP-3

3 1 3 3 2

TUR-1

3 3 2 3 3

UKR-1

3 3 3 2 3

UKR-2 3 3 3 3 3

UKR-3

2 2 3 2 2

UKR-4

3 3 3 3 3

Source: own

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

50

institutions and may reward participation with

extra grades for some courses. Also, at 68,63% of

higher education institutions, students have the

freedom of selecting thesis topics themselves (it is not

forced by the authorities), and the scientific area of

these topics is not limited; thesis can be supervised by

business representatives to make the research more

related to practice.

Finally, analyzing the “Extracurricular Activities”

KPA, it can be seen that 70,51% of the assessed

institutions appear to take levels 3 (“Defined and

managed”) and 4 (“Optimizing”) of personalization

maturity. One of the poorly developed practices here

is “Volunteering”. Following the EPMM cases, such

a level means that HEIs do not engage students in any

volunteer programs, nor do they motivate and reward

participation; they only provide students with

information about existing volunteer programs and

may be engaged in some programs. In turn, the

strongest practice for 70,51% of HEIs is “Personal

development”, which means that these institutions

regularly invite speakers from business units to

conduct classes (workshops, lectures, etc.) for their

students, also engaging students in the search of the

most interesting speakers; they support students in

problems of personal development (tutorship,

mentorship), and frequently inform them about the

most attractive career options offered in the region (or

whole country).

5 DISCUSSION

Nowadays, it is crucial to provide students with the

proper approach toward their preferences and

aspirations for education and personal and

professional development to make them feel content

with their experience at higher education institutions.

Therefore, it is necessary for educational institutions

1) to become aware of whether they give students

enough freedom and flexibility for the realization of

their plans and ambitions; 2) to be able to compare

their personalization policy with other educational

institutions; and 3) to learn about ways of making

their personalization policy more effective.

This paper presents the Education Personalization

Maturity Model developed to assist HEIs in the

assessment of the level of their personalized approach

toward their students.

5.1 Contribution of the Research

The results provided by the Education

Personalization Maturity Model are useful, first of all,

for the higher educational institutions that were

engaged in the survey since the conclusions obtained

allow to pay attention to the weak places of the

process of education personalization development.

Moreover, the authors consider that the descriptions

of cases presented for each practice within each key

process area of the EPMM can serve as kinds of

prompts or small guidelines on what should be

changed or what options should be added to provide

students with a higher level of personalized approach

towards their Individual Profile formation.

Additionally, the authors expect the EPMM to be of

interest to administrative and management staff of

higher educational institutions in countries of Europe

and beyond; the example of 51 HEIs that already took

part in the assessment of personalization should serve

as proof that the EPMM can effectively assist in

personalization assessment, at least at the initial level.

5.2 Limitations of the Research

One of the limitations of the developed EPMM is that

it may miss some practices that might be considered

important for students of HEIs. As stated, the Model

was developed on the basis of students’ opinions, and

the questionnaire presented to them was quite

extensive. Yet, there is a chance that with more

opinions, some new practices would appear. The

authors also believe that a survey conducted among

academic teachers may have given interesting results.

The other limitation of the EPMM consists in the

necessity of finding experts to use it. An employee of

a HEI, who is going to use the Model to assess

personalization at that particular institution, should

possess knowledge about various activities taking

place there: didactic process and research, sports and

other activities, mobility programs and cooperation,

etc.

The limitation of verification of the EPMM,

presented in this paper, is that only one expert from

each HEI used the EPMM. For a better, complete

picture of each institution, at least a few opinions

about each HEI would be necessary.

5.3 Avenues for Future Research

As mentioned earlier, the EPMM is supposed to have

a continuous process of evolution; it can be modified

by the authors or by other users (like the

administrative staff of a HEI) that would like to apply

the Model. Amendments to the EPMM can be

conducted to adjust it to the specificity of a particular

HEI or to the education policy of a certain country.

The authors also believe that the changes that might

Maturity Model for Assessment of Personalization of Higher Education

51

happen to the EPMM will be caused by the natural

changes in higher education – connected with the

flow of time, with the progress of IT, with higher

demands and greater ambitions of students, with the

constants self-development of teachers and

improvement of their teaching techniques, etc.

Therefore, the authors distinguish two directions

for future work. The first one would be the

modification and improvement of the Education

Personalization Maturity Model. The second

direction would be the development of guidelines for

personalization maturity improvement. For now, the

only piece of advice that can be obtained from the

EPMM can be found in the descriptions of particular

practices. Descriptions of the levels higher than the

one defined for the analyzed higher education

institution can serve as small prompts on what

measures to take to improve the level of

personalization and make students of this institution

more content. Thus, the extended guidelines on how

to improve personalization by performing changes in

particular KPAs of institutions’ activity or in

particular practices that they perform would be a

valuable potential contribution to higher education

management.

5.4 Final Remarks

Results of analysis of the selected higher education

institutions with the help of the Education

Personalization Maturity Model, developed by the

authors, lead to a conclusion that HEIs, represented

by their administrative and management staff, may

benefit from the application of the EPMM.

Implementation of the Model enables assessment of

the level (i.e., degree) of the personalized approach

that higher education institutions provide for their

students. It also provides suggestions on possible

ways of improving the current situation with the

personalization of education.

REFERENCES

Aliyu, A., Maglaras, L., He, Y., Yevseyeva, I., Boiten, E.,

Cook, A., & Janicke, H. (2020). A holistic

cybersecurity maturity assessment framework for

higher education institutions in the United Kingdom.

Applied Sciences (Switzerland), 10(10). https://doi.

org/10.3390/app10103660

Anicic, K. P., & Divjak, B. (2020). Maturity Model for

Supporting Graduates’ Early Careers Within Higher

Education Institutions. SAGE OPEN, 10(1). https://doi.

org/10.1177/2158244019898733

Boughzala, I., & de Vreede, G.-J. (2015). Evaluating Team

Collaboration Quality: The Development and Field

Application of a Collaboration Maturity Model.

Journal of Management Information Systems, 32(3),

129–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2015.109

5042

Carvalho, J. V., Pereira, R. H., & Rocha, A. (2019).

Development Methodology of a Higher Education

Institutions Maturity Model. In Xhafa, F and Barolli, L

and Gregus, M (Ed.), Advances in Intelligent Networking

and Collaborative Systems (Vol.23, pp. 262–272).

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98557-2\_24

de Bruin, T., Rosemann, M., Freeze, R., & Kulkarni, U.

(2005). Understanding the main phases of developing a

maturity assessment model. ACIS 2005 Proceedings -

16th Australasian Conference on Information Systems,

8–19.

Dean, A., & Gibbs, P. (2015). Student satisfaction or

happiness? A preliminary rethink of what is important

in the student experience. Quality Assurance in

Education, 23(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/https:/

/doi.org/10.1108/QAE-10-2013-0044

Durek, V., Kadoic, N., & Begicevic Redep, N. (2018).

Assessing the digital maturity level of higher education

institutions. In 2018 41st International Convention on

Information and Communication Technology,

Electronics and Microelectronics, MIPRO 2018 -

Proceedings (pp. 671–676).

Enke, J., Glass, R., & Metternich, J. (2017). Introducing a

Maturity Model for Learning Factories. Procedia

Manufacturing, 9, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.promfg.2017.04.010

Grundspenkis, J. (2010). MIPITS and IKAS--Two Steps

towards Truly Intelligent Tutoring System Based on

Integration of Knowledge Management and Multiagent

Techniques. International Conference on E-Learning

and the Knowledge Society (e-Learning 2010), Riga,

Latvia, August, 26–27.

Hong, Y., & Xinyi, Z. (2019). Mapping algorithm design

and maturity model construction of online learning

process goals. International Journal of Emerging

Technologies in Learning, 14(4), 31–43.

Kabak, M., & Dagdeviren, M. (2014). A hybrid MCDM

approach to assess the sustainability of students’

preferences for university selection. Technological and

Economic Development of Economy, 20(3), 391–418.

https://doi.org/10.3846/20294913.2014.883340

Marshall, S. (2010). A Quality Framework for Continuous

Improvement of E-learning: The E-learning Maturity

Model. Journal of Distance Education Revue De

L’Éducation À Distance, 24(1), 143–166.

Marshall, S., & Mitchell, G. (2004). Applying SPICE to e-

Learning: An e-Learning maturity model? Sixth

Australasian Computing Education Conference

(ACE2004), 30(Ims 2003), 185–191.

Matkovic, P., Pavlicevic, V., & Tumbas, P. (2017).

Assessment of Business Process Maturity in Higher

Education. INTED2017 Proceedings, 1(March), 6891–

6898. https://doi.org/10.21125/inted.2017.1600

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

52

Mettler, T. (2011). Thinking in Terms of Design Decisions

When Developing Maturity Models. International

Journal of Strategic Decision Sciences, 1(4), 76–87.

https://doi.org/10.4018/jsds.2010100105

Nelson, K., Clarke, J., & Stoodley, I. (2014). An

exploration of the Maturity Model concept as a vehicle

for higher education institutions to assess their

capability to address student engagement. A work in

progress. Ergo, 3(1), 29–36.

Nsamba, A. (2019). Maturity levels of student Support E-

services within an open distance E-learning University.

International Review of Research in Open and Distance

Learning, 20(4), 61–78.

Orîndaru, A. (2015). Changing Perspectives on Students in

Higher Education. Procedia Economics and Finance.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s2212-5671(15)01049-7

Penafiel, M., Lujan-Mora, S., Stefanie Vasquez, M.,

Zaldumbide, J., Cevallos, A., & Vasquez, D. (2017).

Application of E-learning Maturity Model in Higher

Education. In I. Chova, LG and Martinez, AL and

Torres (Ed.), 9th International Conference on

Education and New Learning Technologies

(EDULEARN17) (pp. 4396–4404). Lauri Volpi 6,

Valenica, Burjassot 46100, Spain: IATED-INT Assoc

Technology Education & Development.

Quaye, S. J., & Harper, S. R. (Eds.). (2014). Student

Engagement in Higher Education: Theoretical

Perspectives and Practical Approaches for Diverse

Populations (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/

10.4324/9780203810163

Reçi, E., & Bollin, A. (2017). Managing the Quality of

Teaching in Computer Science Education. In

Proceedings of the 6th Computer Science Education

Research Conference (pp. 38–47). New York, NY,

USA: Association for Computing Machinery.

https://doi.org/10.1145/3162087.3162097

Reçi, E., & Bollin, A. (2019). A Teaching Process Oriented

Model for Quality Assurance in Education - Usability

and Acceptability. IFIP Advances in Information and

Communication Technology, 524, 128–137. https://

doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23513-0_13

Rizun, M. (2021). Assessing the Personalization of Higher

Education: Maturity Framework Development. In B. Z.

Janusz Nesterak (Ed.), Knowledge Economy Society.

Business Development in Digital Economy and

COVID-19 Crisis (pp. 195–206). Institute of

Economics Polish Academy of Science.

Rollande, R. (2015). Research and Implementation of

Personalized Study Planning as a Component of

Pedagogical Module. Doctoral Thesis. Riga: RTU.

Rollande, R., & Grundspenkis, J. (2016). Personalized

Planning of Study Course Structure Using Concept

Maps and Their Analysis. Procedia Computer Science.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2017.01.093

Secundo, G., Elena-Perez, S., Martinaitis, Ž., & Leitner, K.

H. (2015). An intellectual capital maturity model

(ICMM) to improve strategic management in European

universities: A dynamic approach. Journal of

Intellectual Capital, 16(2), 419–442. https://doi.org/

10.1108/JIC-06-2014-0072

Thong, C. L., Jusoh, Y. Y., Abdullah, R., & Alwi, N. H.

(2013). Application of curriculum design maturity

model at private institution of higher learning in

Malaysia: A case study. Lecture Notes in Electrical

Engineering, 229 LNEE, 579–590.

Thong, C. L., Yusmadi, Y. J., Rusli, A., & Nor Hayati, A.

(2012). Applying capability maturity model to

curriculum design: A case study at private institution of

higher learning in Malaysia. In Lecture Notes in

Engineering and Computer Science (Vol. 2198, pp.

1070–1075).

Zhu, Y. (2016). Research on Personalized Education in

Chinese Universities. 2016 2nd International

Conference on Social Science and Development

(ICSSD 2016), 138–144.

Maturity Model for Assessment of Personalization of Higher Education

53