Identifying and Assessing Knowledge Gaps in ISO 9001 Certified SMEs

using a Knowledge Audit Framework

Arno Rottensteiner

a

and Christian Ploder

b

Management, Communication and IT, MCI Management Center Innsbruck, Universitaetsstrasse 15, Innsbruck, Austria

Keywords:

Knowledge Management, Knowledge Audit Framework, SME.

Abstract:

The importance of knowledge management in ISO 9001 certified Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SME)

gained importance over the past few years. A company-wide knowledge base could not only improve the

central organizational decision-making, but furthermore contribute to sustainably preserving and expanding

competitive advantages based on proper knowledge management (Ayinde et al., 2021). Therefore, the paper

aims is to present a Knowledge Audit Framework, especially for ISO 9001 certified SMEs based on current

theories and described for practical implementation. The framework will additionally help these ISO 9001

certified SMEs to manage relevant business processes and moreover improve the crucial documentation of

several knowledge-intensive business processes. The framework is derived from current research and em-

pirically based on the case study research method combining a participating observation, direct observation

during a focus group workshop, and a structured questionnaire in order to prioritize the evaluated knowledge

gaps. This prioritized listing of gaps builds the basis for efficient knowledge management improvements in

the organization and the implementation of necessary measures in the field of knowledge management.

1 INTRODUCTION

With an increasing number of organizations recog-

nizing knowledge as an integral part of their sustain-

able competitive advantage, the need for developing

and managing this intellectual expertise gained im-

portance over the last few years (Durst and Runar Ed-

vardsson, 2012). Especially for Small and Medium-

Sized Enterprises the establishment of a knowledge

management strategy often entails different chal-

lenges usually caused by a general constraint of re-

sources and a concentration of power in most SMEs

(Bridge and O’Neill, 2018). Foreseeing these dif-

ficulties often leads to not implementing organiza-

tional knowledge management systems in SMEs and

instead subsequently counting on the intellectual ex-

pertise anchored in employees’ minds (Yew Wong

and Aspinwall, 2004). To facilitate and support the

initial step of implementing a sustainable knowledge

management system in SMEs, this paper will pro-

pose a framework to collect existing organizational

knowledge, identify the gap between documented and

non-documented knowledge and assess the identified

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1871-025X

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7064-8465

knowledge gap. Probst (1998) additionally highlights

the importance of identifying and assessing the exist-

ing knowledge before implementing different organi-

zational knowledge measures. Inconsistencies in the

knowledge identification process will not only influ-

ence the quality of the knowledge management sys-

tem but furthermore lead ”to inefficiency, uninformed

decisions, and redundant activities” within the com-

pany (Probst, 1998, p. 21). After a general introduc-

tion to the topics of knowledge, knowledge manage-

ment, knowledge audit, and the different processes

used for managing intellectual expertise, section 3

will focus on a detailed description of the suggested

framework and the methodological approach used for

designing the Knowledge Audit Framework. The pa-

per will be concluded by reflecting on the limitations

of the framework and furthermore highlighting poten-

tial applications in terms of further research.

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

The following section will focus on the theoretical

foundation for this paper. After defining knowledge

itself and its categorization into tacit and explicit

knowledge, the topic of knowledge management will

158

Rottensteiner, A. and Ploder, C.

Identifying and Assessing Knowledge Gaps in ISO 9001 Certified SMEs using a Knowledge Audit Framework.

DOI: 10.5220/0011539600003335

In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2022) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 158-162

ISBN: 978-989-758-614-9; ISSN: 2184-3228

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

be introduced as well as the concept of knowledge au-

dits.

2.1 Definitions of Knowledge

In order to implement a successful knowledge man-

agement system, a solid understanding of knowledge

and its characteristics is crucial. There are two main

ways of defining the term knowledge. Whereas Epis-

temologists explore the topic of knowledge from a

more philosophical point of view (Bolisani and Bra-

tianu, 2018), most definitions used in the field of

knowledge management base their interpretations on

the underlying data contributing to the generation

of intellectual expertise by relying on the so-called

DIKW-hierarchy designed by Ackoff (1989). This hi-

erarchy describes the interconnection between Data,

Information, Knowledge and Wisdom. According

to Ackoff (1989), data can be described as randomly

concatenated symbols. When this data is further pro-

cessed in order to fit in a predefined context, the next

level in the DIKW-hierarchy can be reached. As

soon as the information is enriched by human ex-

perience knowledge is generated. Only understand-

ing the generated knowledge and interpreting it us-

ing intelligence will lead to the final hierarchical step

called Wisdom. To further refine the DIKW model,

North (2011) proposed a redesign of the hierarchy

by adding three more dimensions and arranging them

in so-called ”Knowledge Steps”. By applying this

framework, North (2011, p. 37) defines knowledge

as ”[...] the process of the purposeful interconnec-

tion of information”. Probst (1998, p.23) on the other

hand defines knowledge in a business context by re-

ferring to it as ”[...] the totality of knowledge and

skills that individuals use to solve problems. This in-

cludes theoretical knowledge as well as practical ev-

eryday rules and instructions for action”. In an at-

tempt to further classify knowledge based on its char-

acteristics Nonaka and Peltokorpi (2006) distinguish

between tacit and explicit knowledge. Howells (1996,

p.92) describes tacit knowledge as ”non-codified, dis-

embodied know-how that is acquired via the infor-

mal take-up of learned behaviour and procedures”.

Especially the learning aspect can be recognized as

one of the key processes when it comes to generat-

ing tacit knowledge (Howells, 1996). As this type of

knowledge mainly originates from experience and is

used subconsciously, documenting this knowledge of-

ten presents a challenge for SMEs. Sternberg (1997)

furthermore underlines the challenge of documenta-

tion by pointing out the characteristics of tacit knowl-

edge being highly individual and subjective. Explicit

knowledge on the other hand can be described as

more objective knowledge that can be ”expressed in

words and numbers and shared in the form of data,

scientific formulas, specifications, manuals, and the

like” (Lee et al., 2006, p. 153). Additionally to the

advantage of documentation mentioned in the previ-

ous paragraph, explicit knowledge can be furthermore

clustered using keywords which simplifies the search-

ing of the documented knowledge

2.2 Introduction to Knowledge

Management

The first endeavors of managing intellectual expertise

can be found in ancient roman culture where peo-

ple started to document information about civiliza-

tion, commercial contracts, and governmental pro-

cesses (Sveiby, 1997). Whereas this information was

only accessible to an exclusive and selected group of

people, the establishment of community libraries pro-

vided a broader audience with the possibility to access

knowledge in an easy and structured way (Ives et al.,

1997). With different technical and organizational de-

velopments in the following years, knowledge man-

agement evolved to what is now deemed as one of the

central processes in establishing and maintaining mar-

ket competitiveness (Teece and Pisano, 1994). Ac-

cording to Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995, p. 3) knowl-

edge management comprises all organization’s ca-

pabilities “to create new knowledge, disseminate it

throughout the organization, and embody it in prod-

ucts, services, and systems”. Whereas Nonaka’s and

Takeuchi’s definition primarily focuses on the three

processes of creating, disseminating and embodying

knowledge, Probst (1998) extended this definition by

adding three additional operational knowledge pro-

cesses: (1) knowledge identification, (2) knowledge

acquisition, and (3) knowledge preservation. To align

the knowledge management strategy with the gen-

eral strategy of the organization an additional strate-

gic layer was introduced, including the definition of

knowledge goals at the beginning and concluding

the cycle with knowledge measurements. Follow-

ing the cycle of ”Knowledge Blocks” according to

Probst (1998) will not only help to define a knowledge

management strategy but furthermore also constantly

improve and re-assess the strategy and measures in

place.

2.3 Knowledge Audit

Based on the strategic re-assessment in the concept of

Probst (1998), knowledge audit supports reaching the

knowledge goals which have to be in line with the or-

ganizational objectives. Therefore, periodic reviews

Identifying and Assessing Knowledge Gaps in ISO 9001 Certified SMEs using a Knowledge Audit Framework

159

and corresponding evaluation of the existing knowl-

edge has to be performed and documented for further

improvement. This is also a demand for the continu-

ous improvement required by the ISO 9001 and other

quality management norms. It is crucial to find out

where the gaps in knowledge assets and duplicates

of knowledge in the organization can be identified

(Ayinde et al., 2021). By far not all of the knowl-

edge in companies is documented in the right way or

at all. According to Serrat (2017) around 80 % of an

organization’s intellectual expertise is represented in

tacit knowledge. This poses the challenge of iden-

tifying these knowledge parts, documenting, and au-

diting them to achieve organizational objectives. The

Knowledge Audit Framework presented in the next

chapter will exactly offer an option for that.

With the necessity of process management given

by quality management norms, it is important for

SMEs to focus on the most valuable business pro-

cesses and their improvement. With that in mind, it is

crucial to identify the knowledge-intensive business

processes (Ploder, 2020) and start improving their

knowledge documentation first. Identifying these

knowledge-intensive business processes helps to fo-

cus and use the limited resources in SMEs efficiently.

Overall, certified organizations need to intensify

the managed knowledge audit activities combined

with the ISO 9001 audit requirements. To support

SMEs in assessing the available knowledge, the au-

dit aspect will be a fundamental part of the developed

framework shown in section 3.

3 THE KNOWLEDGE AUDIT

FRAMEWORK

Based on the given theoretical concepts in section 2

this chapter explains the development and the struc-

ture of the final Knowledge Audit Framework for ISO

9001 certified SMEs with a special focus on the core

processes rooted in the business process management

theory (Dumas et al., 2018) and also included in all

quality management related norms. Based on the

concept of knowledge-intensive business processes,

their measurement, and their importance for compa-

nies (Ploder, 2020), it is beneficial to use the core

processes as a starting point for the knowledge audit.

This suggestion can be also supported by the fact that

managing processes represent a base requirement for

ISO 9001 certified companies.

The aforementioned process focus combined with

the active management of knowledge is also required

from a quality management perspective. The given

norms which are applicable for SMEs in different in-

dustries could be ISO 9001:2015, ISO 13485:2016,

and others. Especially the requirements given in the

changed ISO 9001:2015 within clause 7.1.6 can be

mentioned which directly calls for the knowledge

which is necessary to establish high-quality products

and services besides the necessity to safe the knowl-

edge in the organizations. Additional to the described

clause 7.1.6 also clauses 7.2 addresses the competen-

cies and skills of employees and clause 7.5 addresses

the documentation of information. Clause 7.1.5 fur-

thermore addresses the active management of knowl-

edge in line with quality standards (Ayinde et al.,

2021).

To combine the given requirements in SMEs the

authors used the concept of a case study design by

Yin (2009) which includes at least a triangulation of

methods to answer a given research question based

on a single case study (Yin, 2009). The necessary

steps within the case study are defined as follows:

(1) designing of the case study, (2) preparation and

planning of collection of evidence, (3) collection of

the case study evidence, (4) analysis of the evidence

and (5) reporting of the outcomes. This paper will

focus on steps 1 and 2 only, steps 3 to 5 will be re-

ported after the implementation which is planned for

Q4 2022 to validate the concept together with a coop-

eration partner which is an ISO 9001:2015 certified

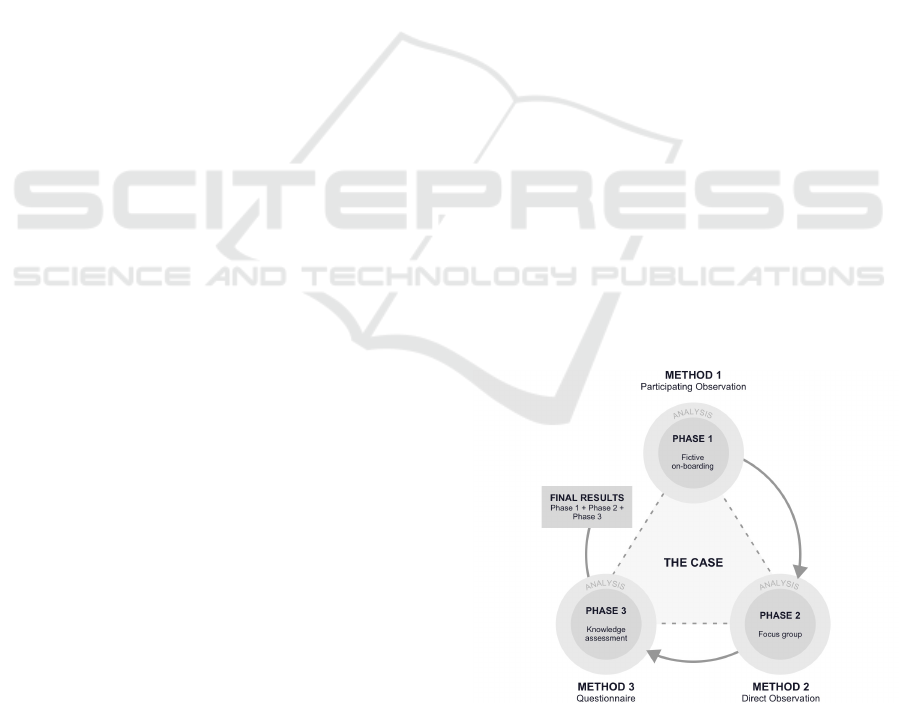

SME in Austria. The aim of the framework displayed

in figure 1 is to identify the status quo of knowledge

management at the company and develop an optimum

status of knowledge management. By the comparison

of the as-is status with the should-be status, the po-

tential knowledge gap between documented and non-

documented process knowledge will be identified.

Figure 1: Knowledge Audit Framework.

A crucial part of the first step is the definition

of the research question for the planned case study.

Based on the given explanations and theoretical back-

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

160

ground the following research question will be tack-

led within this case study: How to conduct a knowl-

edge audit to identify and overcome an organiza-

tional knowledge gap between documented and non-

documented knowledge? To answer this research

question the authors have chosen the methodology of

participating observation in phase 1 (DeWalt and De-

Walt, 2011) to get an explanation of the current state

of needed and documented knowledge in the com-

pany. It is planned that one of the authors is part of

a fictive on-boarding phase in one department docu-

menting all the information which is gained through

this first observation in a field diary with all pieces of

evidence that are given to a new employee. Based on

the observed information a first as-is process model

will be established based on the BPMN 2.0 ((OMG)

Object Management Group, 2013) syntax and the cor-

responding knowledge evidence are mapped to the ex-

isting process. After the as-is analysis, an improved

to-be process model will be developed by the authors,

simply based on the given evidence and inputs during

the on-boarding process. This to-be process model

will build the foundation for the following phase.

For phase 2 the authors will use the methodol-

ogy of a focus group workshop to reflect on the de-

signed to-be process together with the experts in the

company and to unveil the different knowledge gaps

which can be based on missing sharing in the on-

boarding phase or on changes in the to-be process

which also has to be discussed during the focus group

session. The aim of the second methodological ap-

proach is to gain insights into the potential knowl-

edge gaps by comparing the knowledge needs from

the focus group session with the documented knowl-

edge collected from phase 1.

Phase 3 will afterward focus on the prioritization

of the identified knowledge gaps. From a resource

point of view, especially for SMEs with highly re-

stricted resources, a prioritization of the gaps can help

to overcome the shortcomings in a quick and orga-

nized way. For this analysis, the authors base the pri-

oritization on the model of Magnier-Watanabe (2015)

which will be distributed as an online questionnaire

based on the gaps from phase 2. The concept is

based on measuring two dimensions of knowledge:

breadth and depth. Whereas knowledge breadth refers

to the diversity of knowledge and whether knowl-

edge is limited to a single domain (narrow) or spans

over multiple disciplines (broad), the depth of knowl-

edge describes the complexity of the knowledge and

the characteristic of whether it is superficial and eas-

ily traceable (shallow) or deeply anchored (deep), so-

called know-how. In order to assess and quantify the

previously identified knowledge gap, a classification

scheme by Magnier-Watanabe (2015) was selected

and extended to a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from

very narrow to very broad and very shallow to very

deep, to cater to the needs of phase 3 and eliminating

the choice of a neutral answer. The output of phase 3

will be a prioritized list of all knowledge gaps which

should be tackled in the further course of implement-

ing knowledge management measures.

The three phases in the proposed framework

should then be implemented in the company-wide

yearly audit plan to guarantee the re-evaluation based

on the framework to ensure not falling to a worse po-

sition by changes that are not covered in the current

knowledge documentation. This also helps to assure

the accuracy of the required quality management-

related documentation as well.

4 LIMITATIONS & FUTURE

RESEARCH

In conclusion, this paper suggests a framework to

identify and implement measures to overcome an or-

ganizational gap between documented and undocu-

mented knowledge. This could help to overcome cur-

rent flaws in the field of knowledge management, in-

crease the effectiveness of sharing intellectual exper-

tise, and optimize internal processes associated to the

different phases of knowledge management. As the

framework described in this paper should only serve

as a proposal based on relevant literature, the obvi-

ous limitation of this publication lies in the currently

missing application and evaluation of the model us-

ing real-life data. The application and evaluation of

the suggested framework is planned to be executed in

Q4 of 2022 with a cooperating Austrian company cer-

tified in ISO 9001. After the first implementation, the

applicability of this framework for SMEs in special

will be evaluated and adapted if necessary for further

implementations. In terms of additional research op-

portunities, the evaluation of the framework could be

expanded geographically and to diverse sectors. Fur-

thermore it would add value and help to improve the

suggested framework by linking it to the information

audit theory (Heisig et al., 2020) to later come up

with an expanded concept for practical use in ISO

9001 certified SMEs. This expansion will addition-

ally focus on the more technical aspects of knowledge

transfer based on the understanding of data gathering

and data structuring (Buchanan and Gibb, 2008; Jones

et al., 2013).

Identifying and Assessing Knowledge Gaps in ISO 9001 Certified SMEs using a Knowledge Audit Framework

161

REFERENCES

Ackoff, R. (1989). From data to wisdom. Journal of Applied

Systems Analysis, 15:3–9.

Ayinde, L., Orekoya, I. O., Adepeju, Q. A., and Shomoye,

A. M. (2021). Knowledge audit as an important tool

in organizational management: A review of literature.

Business Information Review, 38(2):89–102.

Bolisani, E. and Bratianu, C. (2018). The Elusive Definition

of Knowledge. In Emergent Knowledge Strategies,

volume 4, pages 1–22. Springer International Publish-

ing, Cham. Series Title: Knowledge Management and

Organizational Learning.

Bridge, S. and O’Neill, K. (2018). Understanding enter-

prise: entrepreneurs & small business. Palgrave, Lon-

don, fifth edition edition.

Buchanan, S. and Gibb, F. (2008). The information audit:

Theory versus practice. International Journal of In-

formation Management, 28(3):150–160.

DeWalt, K. M. and DeWalt, B. R. (2011). Participant ob-

servation: a guide for fieldworkers. Rowman & Lit-

tlefield, Md, Lanham, Md, 2nd ed edition. OCLC:

ocn656213202.

Dumas, M., La Rosa, M., Mendling, J., and Reijers, H. A.

(2018). Introduction to Business Process Manage-

ment. In Fundamentals of Business Process Manage-

ment, pages 1–33. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin,

Heidelberg.

Durst, S. and Runar Edvardsson, I. (2012). Knowledge

management in SMEs: a literature review. Journal

of Knowledge Management, 16(6):879–903.

Heisig, P., Ogaza, M. A., and Hamraz, B. (2020). In-

formation and knowledge assessment – Results from

a multinational automotive company. International

Journal of Information Management, 54:102137.

Howells, J. (1996). Tacit knowledge. Technology Analysis

& Strategic Management, 8(2):91–106.

Ives, W., Torrey, B., and Gordon, C. (1997). Knowl-

edge Management: An Emerging Discipline with a

Long History. Journal of Knowledge Management,

1(4):269–274.

Jones, A., Mutch, A., and Valero-Silva, N. (2013). Ex-

ploring information flows at Nottingham City Homes.

International Journal of Information Management,

33(2):291–299.

Lee, C. K., Foo, S., and Goh, D. (2006). On the Concept

and Types of Knowledge. Journal of Information &

Knowledge Management, 05(02):151–163.

Magnier-Watanabe, R. (2015). Recognizing knowledge as

economic factor: A typology. In 2015 Portland Inter-

national Conference on Management of Engineering

and Technology (PICMET), pages 1279–1286, Port-

land, OR, USA. IEEE.

Nonaka, I. and Peltokorpi, V. (2006). Objectivity and sub-

jectivity in knowledge management: a review of 20

top articles. Knowledge and Process Management,

13(2):73–82.

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge-

creating company: how Japanese companies create

the dynamics of innovation. Oxford University Press,

New York.

North, K. (2011). Wissensorientierte Un-

ternehmensf

¨

uhrung: Wertsch

¨

opfung durch Wissen.

Gabler, Wiesbaden, 5., aktualisierte und erweiterte

auflage edition.

(OMG) Object Management Group (2013). Business Pro-

cess and Notation (BPMN).

Ploder, C. (2020). A Measurement Model to Identify

Knowledge-intensive Business Processes in SMEs:.

In Proceedings of the 12th International Joint Confer-

ence on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineer-

ing and Knowledge Management, pages 133–139, Bu-

dapest, Hungary. SCITEPRESS - Science and Tech-

nology Publications.

Probst, G. (1998). Practical Knowledge Management: A

Model That Works. page 14.

Serrat, O. (2017). Knowledge Solutions. Springer Singa-

pore, Singapore.

Sternberg, R. J. (1997). Successful intelligence: how practi-

cal and creative intelligence determine success in life.

Plume, New York.

Sveiby, K. E. (1997). The new organizational wealth: man-

aging & measuring knowledge-based assets. Berrett-

Koehler Publishers, San Francisco, 1st ed edition.

Teece, D. and Pisano, G. (1994). The Dynamic Capabilities

of Firms: an Introduction. Industrial and Corporate

Change, 3(3):537–556.

Yew Wong, K. and Aspinwall, E. (2004). Character-

izing knowledge management in the small business

environment. Journal of Knowledge Management,

8(3):44–61.

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: design and meth-

ods. Number v. 5 in Applied social research methods.

Sage Publications, Los Angeles, Calif, 4th ed edition.

KMIS 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

162