Observing the Uncanny Valley: Gender Differences in Perceptions of

Avatar Uncanniness

Jacqueline D. Bailey

a

, Karen L. Blackmore

b

and Robert King

College of Engineering, Science and Environment, University of Newcastle, Ring Road, Callaghan, NSW, Australia

Keywords: Uncanny Valley, Uncanniness, Avatar, Human Computer Interaction, Gender(Sex).

Abstract: The creation of avatars is a two-sided coin; on one side we see developers creating avatars with the skills,

time, and resources available to them. However, these resources (or lack thereof) may lead to avatars falling

into the uncanny valley. On the other side are the end-users who engage with the avatar, who ultimately are

the focus for these designers and developers. However, many factors can influence the perception of any

avatar created beyond the level of realism, including the physical appearance of the avatar or something more

fundamental like its gender(sex). Currently, there is a gap in understanding of the influence of gender(sex) in

avatar uncanniness perceptions, and this is mostly missing in design decisions for avatar systems. Bridging

this gap has been a source of research focus spanning the development of new technologies for avatar

development to measuring end-user perceptions of those avatars. Here we add to this discussion through an

experiment involving a set of avatars presented to participants (n = 2065) who were asked to rank them from

least to most uncanny based on their perceptions. This representative set of avatars were sourced from publicly

available methods and have different levels of realism. Our findings indicate that perceptions of avatar

uncanniness based on gender(sex) affects the overall perception of the avatar.

1 INTRODUCTION

‘Avatar’ is a common term that often refers to virtual

humans in virtual environments. Originally derived

from the Sanskrit word ‘Avatara’, referring to the

descent of a god down into the mortal world (Adams,

2014), the term also appears in novels and literature

(Stephenson, 1993). Avatars are often associated with

virtual humans in serious gaming and simulation

training scenarios.

Many factors influence the perception avatars,

including aspects of their aesthetic characteristics

such as hair colour, clothing, and gender(sex) (Fox et

al., 2013). This can also include perceived avatar

realism and uncanniness, which particularly affect to

avatar faces. The differentiation between aesthetic

and perceived characteristics may blur, for example,

where a characteristic such as realism may impact on

the look of an avatar and be the result of the tools used

to create an avatar. This can also be influenced by

how the avatar is presented (fully body or head and

shoulders). These complex interactions present

challenges for designers.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8550-902X

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9111-0293

The focus of this work is an examination of

gender(sex) in end-user uncanniness perceptions of

avatar faces. Similar to the work of Stumpf et al.

(2020), we use the social construct perspective of

gender, here referred to as gender(sex), whereby

gender identification, gender expression and

performance might not necessarily align with sex.

There are numerous techniques available to create

avatars, however, issues such as available time, funds,

and other resource constraints impact the quality of

the avatar’s appearance and animation. This is true for

avatar face animation where subtle communication

cues may be required. The quality of avatar face

animation is dependent on several factors, first

determined by the fidelity of the 3Dimensional

models and textures used to represent a human face.

Creating highly realistic 3Dimensional models to

represent human faces can be achieved using

techniques such as linear transformations (Tewari et

al., 2017; Thies et al., 2015) and higher-order tensor

generalizations (Brunton et al., 2014). Data-driven

approaches can also be used to create highly realistic

textures of human faces (Saito et al., 2017). With the

Bailey, J., Blackmore, K. and King, R.

Observing the Uncanny Valley: Gender Differences in Perceptions of Avatar Uncanniness.

DOI: 10.5220/0011576000003323

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications (CHIRA 2022), pages 209-216

ISBN: 978-989-758-609-5; ISSN: 2184-3244

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

209

emergence of approaches, the realism of human faces

for avatars may increase, however, this is not yet the

case in many practical applications.

The level of realism of an avatar ideally meets

end-users expectations without the feeling of

uncanniness affecting their experience (MacDorman

et al., 2009). When designing avatars, some explicit

consideration of these issues is valuable, including

the possible interrelationship with gender(sex) and

uncanniness. Various perceptions can be affected by

gender(sex), such as physical attractiveness and

authority (Patel & MacDorman, 2015). Accordingly,

this research seeks to further explore the

interrelationship of observer gender(sex) on the

perception of avatar uncanniness levels. We achieve

this through a large-scale avatar ranking exercise

considering the differences in avatar rankings based

on the gender(sex) of participants. The goal is to

evaluate whether gender(sex) has an impact on the

perception of avatar uncanniness, and to generate a

robust set of ranked avatars.

Ultimately, this information is important to

inform design considerations for avatars, and

particularly for avatars that may be used in serious

games and training applications. Through this

research, we propose that avatar creators adopt a more

purposeful consideration of gender(sex) in design

considerations for avatar-based systems. This may

lead to enhanced affective outcomes for avatars in

serious purposes.

The following section provides a review of

relevant literature followed by the methodology for

our study. Next, the results of the research detail the

overall uncanniness ranks as well as potential impacts

of participant gender(sex) on these ranks. We

conclude with a discussion of the key findings,

together with recommendations for future work.

2 BACKGROUNDS

Uncanniness can apply to an avatar when a human

like avatar fails to meet the expected visual, kinetic,

or behavioural fidelity of a human. This negative

emotional response can be attributed to the Uncanny

Valley theory proposed by Mori in 1970 (Figure 1)

and is demonstrated through a sharp dip in the linear

progression of the perception of human likeness.

Mori suggests that the sense of eeriness is likely a

form of instinct that protects us from proximal, rather

than distal sources of danger, such as corpses or

members of different species. This theory has now

also been applied to human-like avatars that have

been created using computer graphic capabilities with

a

Figure 1: The Uncanny Valley (Mori et al., 2012).

a focus on boundary-pushing realism (Tinwell, 2014).

The theory states that the human-like entities, such as

avatars, that fail to meet expectations of human

behaviour fall into the Uncanny Valley, which may

stem from the consequences of realism levels seen in

avatar faces.

2.1 The Consequences of Uncanniness

Perceptions for Avatar Faces

The potential impact of uncanniness is an important

issue in the perception of avatars that should be

considered carefully. In particular, as the human

visual system excels in detecting falsehoods that may

be found in human-like facial features based on prior

knowledge of human facial features (Seyama &

Nagayama, 2007), avatars are particularly susceptible

to uncanny valley effects. These issues extend to

more than just the visual representation though.

Another key factor of avatar face animation is the

approach used to make the avatar face move and

express emotions in realistic ways. There are several

methods used to create facial animation, including

manual, motion capture, and data-driven approaches.

Traditional manual methods can include a frame-by-

frame approach or rotoscoping of facial movements.

While these manual animation methods can

effectively create facial animation, it is a highly time-

consuming process. Alternatively, techniques such as

motion capture provide a quicker means of capturing

an actor’s facial movement. These movements can be

captured as a live performance through real-time

motion capture or as a set of motions mapped post-

capture (Davison et al., 2001). Little is understood

though of the impacts of these different techniques on

perceptions of uncanniness.

Thus, based on this existing research, we

undertake a ranking exercise with a set of relatively

homogenous avatars to better understand perceptual

variability, and to create a robustly ranked set of

avatars for future research. With these avatars

CHIRA 2022 - 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

210

quantifiability rated in terms of uncanniness

perceptions, further analysis can be carried out from

additional data collected on this avatar set

. While the

set of avatars used in our study are of similar age and

ethnicity, they are distinctly different with varying

levels of realism as used by Seymour, Riemer

Seymour et al. (2018) and Seyama and Nagayama

(2007). In summary, we investigate the relationship

between a set of avatar faces uncanniness perceptions

and how gender(sex) may affect these perceptions.

2.2 Impact of Avatar Gender(Sex)

One fundamental aspect of avatar creation is the

perceived gender(sex) of the avatar. There has been

some research in this area, with issues such as

existing gender(sex) stereotypes, the proteus effect,

and gender(sex) swapping being explored. Some

gender(sex) based stereotypes were observed by Fox

and Bailenson (2009) who suggested that female

avatars are more likely to appear either as hyper

sexualised as an ornament within games or as a

support role. The level of sexualisation of an avatar

can also affect their perceived abilities (Wang & Yeh,

2013). When considering the Proteus Effect, Yee and

Bailenson (2007) suggest that the appearance of an

avatar will lead users to conform to behavioural

expectations they have associated with a specific

gender(sex). For example, Beltrán (2013) examined

this and suggested that this conformity exists in

simulation and training contexts, finding that using a

male avatar to train professional women can

negatively affect her and her peers' achievements.

This is important to consider, as Beltrán (2013)

argues that most simulation tools show a generic male

avatar during training.

Additionally, gender(sex) swapping and

exploring an end-user's gender identity or identities is

an active area of research. Lehdonvirta et al. (2012)

suggest that male participants are more likely to seek

and receive help when disguised as a female avatar.

Also, Hussain and Griffiths (2008) suggest that there

are many social benefits to gender(sex)-swapping in

online gaming, such as male players engaging as a

female avatar to be more favourably treated by other

male players.

Another aspect of avatar gender(sex) is the ability

for end-users to explore and express their own gender

identity (Baldwin, 2018). This is important as it

allows users to express their gender identities which

may or may not reflect the gender identity they

express in their everyday lives. In video/computer

gaming settings, players may be able to remain

anonymous online while they explore their gender

identity or identities in a safe platform. To examine

the potential influence of gender(sex) in the

perception of avatar uncanniness, we conducted a

mass-scale survey, described next.

3 STUDY METHODOLOGY

Using a set of 10 homogeneous avatars we consider

the impact of participant gender(sex) in the

perception of uncanniness. This data was gathered via

an online Mturk (amazon.com, 2017) study which

took participants 15-20minutes to complete. The

participants were asked to rank the avatars from least

to most uncanny or eerie. This study was approved by

the University of Newcastle’s Human Research

Ethics Committee (H2015-0163).

In total, (n=2065) participants, with a mean age of

34.82 years completed the survey. Of these

participants, 1050 self-identified as female, 1003 as

male, three people self-identified as transgender

people, two people selected ‘other’ for their

gender(sex), and seven preferred not to say.

3.1 Avatar Set

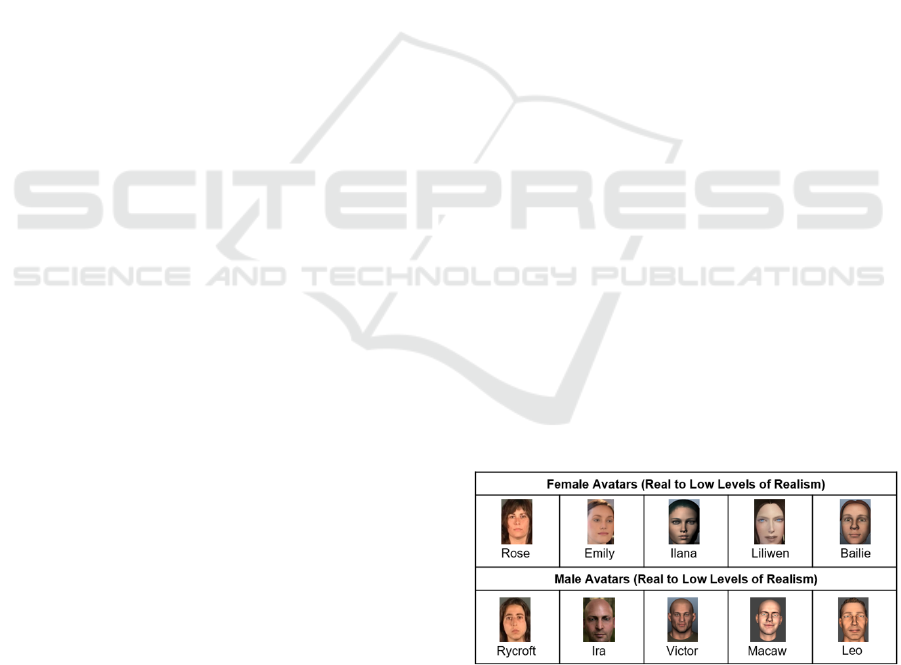

A set of 10 avatar faces (Table 1) was used in this

study to broadly capture the varying levels of realism

obtained through different creation methods. As

shown, they are of different but homogenous faces

with assumed binary sexes (five females and five

males). These avatars are considered representative of

those found in simulation and training contexts, and

are derived from various sources (Alexander et al.,

2017; AppleInc., 2015; Battocchi, 2005; Metrics,

2018; Nao4288, 2013; von der Pahlen et al., 2014).

Table 1: Sample Images of the avatar set.

3.2 Study Procedure

To begin the ranking survey, participants first

completed a set of demographic questions on

gender(sex), age, ethnicity, English language

proficiency, current residential country, and highest

Observing the Uncanny Valley: Gender Differences in Perceptions of Avatar Uncanniness

211

education level achieved. Additional questions asked

participants to nominate whether they identified

themselves as a video/computer gamer, on which

platforms and media they interacted with avatars, and

how many hours a week they spent interacting with

avatars. Participants then ranked the avatar set from

most uncanny to least uncanny. The approach

adopted here follows Lange (2001), who used a

similar rating exercise for their study into realism

perceptions of virtual landscapes. In both cases, a

ranking rather than rating approach is adopted as

these have been shown to have higher reliability

(Mantiuk et al., 2012; Winkler, 2009).

3.3 Statistical Analysis

The avatar uncanniness ranks were first analysed

using Friedman tests. Following a significant

Friedman test, post hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank tests

using a Bonferroni adjustment for multiple tests

(significance level reduced to .0001) were conducted

to examine differences in rankings.

The variable ‘observer gender(sex)’ was

investigated to determine whether the gender(sex) of

a participant was related to the realism and

uncanniness rankings of the avatar faces. To measure

the impact of gender(sex), we used the approach

suggested by (Conover & Iman, 1981) who suggest

that rank transformation procedures allow the use of

parametric methods. This would normally be done

with observed scores being converted to ranks first.

However, in this study, the ranks were provided by

the participants, so the transformation step was not

needed.

The impact of gender(sex)was tested using the

General Linear Model (GLM) as the parametric

procedure. For the effect of observer gender(sex), a

full factorial two-way ANOVA model was fit with

avatar and gender(sex)being the two factors. Follow

up testing with pairwise comparisons were used to

determine significant differences with a Bonferroni

adjustment to control the familywise error rate due to

multiple testing.

4 RESULTS

We first present results of the Friedman tests to

compare the ranks for our avatar set’s uncanniness

perceptions, followed by the impact of participant

gender(sex) on these rankings.

4.1 Uncanniness Ranking Scores

Based on the Freidman test, there was a statistically

significant difference in the perception of the avatars’

uncanniness

χ

2

(9) = 156.254, p < .001. Interestingly,

we see that the means scores for the uncanniness

ranks are all clustered between 4.9-5.8. This suggests

that there is some variation in the uncanniness

perceptions, but it may be very subtle.

The rankings here show that the Mid1 realism

avatars frame the two extremes of these ranks, with

Victor (Mid1 realism male) being rated as the

uncanniest (M= 4.99, SD= 2.505), whereas his female

counterpart Ilana (M= 5.87, SD =2.324) is considered

the least uncanny of the avatars. However, Ira (high

realism male) (M= 5.14, SD= 2.805) was considered

uncannier than his counterpart Emily (M= 5.37, SD=

3.006). Leo (Mid2-Low realism male) was ranked

fourth most uncanny by participants (M= 5.47, SD =

2.739), while Rycroft (real human male) is ranked as

the fifth most uncanny avatar (M = 5.51, SD = 3.114).

Interestingly, Rose (real human female) (M= 5.65,

SD= 3.360) was considered less uncanny than her

counterpart. Despite being considered the least

realistic, the Bailie (M= 5.66, SD= 3.214) avatar was

not considered to be the uncanniest.

A Wilcoxon signed ranked test using a Bonferroni

correction, determined where the differences

occurred for the uncanniness ranks. Although there

were no large differences between the scores for the

avatars, there were some significant differences in the

ranks of the following avatars. When examining the

scores for the high realism male and the real humans,

both comparisons were statistically significant; Ira

and Rycroft (Z = -4.527, p. < 0.001) and Ira and Rose

the real human female (Z = -6.229, p. < 0.001).

However, the scores for Emily (high realism female)

were not statistically significantly different when

compared to real humans, which may suggest that the

gender(sex)of the avatar may influence uncanniness

when compared to real humans. Another pattern

occurs in the comparison of the uncanniness rank for

Victor (Mid1 realism male); it is statistically

significantly different to other avatars, including the

female avatar from the same source. This again may

suggest some gender(sex)-based perceptual

differences.

4.2 The Impact of End-user

Gender(Sex) on the Rank Scores

Following the analysis of differences in the overall

uncanniness rankings, we consider gender(sex)-based

variability in uncanniness ranks. Using a GLM with a

CHIRA 2022 - 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

212

Bonferroni correction, we note a statistically

significant interaction of our avatar set uncanniness

ranks and the participants’ gender(sex) F(9, 19910) =

10.453, p < .001).

The Posthoc analysis shows some statistically

significant differences between the responses of

female and male participants. Specifically, the female

participants rated Rycroft (real human male) as less

uncanny than the male participants (Rycroft p = .001,

(Female (M= 5.68, SD= .093), Male (M= 5.26, SD=

.088))).This pattern continues with scores for Rose

(real human female) where the female participant

scores are higher than the male participants (Rose p <

.001, (Female (M=5.85, SD= .093), Male (M= 5.33,

SD= .088))). The high realism female is less uncanny

by female participants when compared to the male

participants (Emily p = .001, (Female (M= 5.54, SD=

.093), Male (M= 5.12, SD= .088))).

In contrast, the high realism male avatar (Ira) was

ranked uncannier by male participants (Ira p = .005,

(Female (M= 5.27, SD= .093), Male (M= 4.90, SD=

.088))). The independently sourced avatar (Baillie)

was deemed less uncanny by male participants than

the female participants (Bailie p < .001, (Female (M=

5.47, SD= .093), Male (M= 5.98, SD= .088))).

Finally, Macaw (Mid2-Low male avatar) was

regarded as less uncanny by male participants when

compared to scores from female participants (Macaw

p=.001, (Female (M= 5.30, SD= .093), Male (M=

5.75, SD= .088))). Generally, male participants are

more likely to rank high realism avatars as uncanny.

Further, we note limited variation in the responses

as the scores only vary in a range between 4.5 and 6.5

when compared by participant gender(sex). However,

when examining the distribution of uncanniness

scores for each avatar and grouped by participant

gender(sex), several patterns emerge as shown in

Figure 2.

The initial comparison considers differences in

the distributions of the uncanniness scores for each

avatar for female and male participant responses.

From these histograms (Figure 2), we observe the

Mid1 avatars (Ilana and Victor) and the Mid2-Low

male avatar (Macaw) scores resemble a normal

distribution. In contrast, Rose and Rycroft (real-world

humans) and the Mid2-Low female avatar (Bailie)

scores have a distinctly bi-modal distribution

indicating participants have a divided opinion of these

avatars. The remaining avatars present a somewhat

flat, uniform like distribution of scores.

Using a 2 sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test to

compare the shapes of the distributions, and with a

Bonferroni correction for testing multiple pairs, we

compared the female and male participant

Figure 2: Rank scores comparison by avatar and participant

gender(sex).

uncanniness score distributions. We see statistically

significant differences in the distribution of the scores

for some avatars when comparing the female and

male distributions, including Macaw D(1993) =

1.796, p.= .003, Rose D(1993) = 1.785, p.< .001,

Bailie D(1993) = 1.785, p.= .003 and Rycroft

D(1993) = 1.819, p.= 003.

The second key comparison is an examination of

the differences in the distribution of scores when

comparing avatars between female and male

participants. Using a series of Kolmogorov-Smirnov

Tests, with a Bonferroni correction to examine these

differences, reveals some statistically significant

differences. When comparing Leo – Liliwen, the

distribution of the female scores were statistically

different while the male participants scores were not

(Female(D(2090) = 1.947, p.< .001., Male (D(1896)

= 1.355, p.= .051.)). We also note that the female

participant scores when comparing Rose (real human

female) and Emily (high realism female) are

statistically different when to the male participant

scores (Female (D(2090) =3.412, p.< .001.), Male

(D(1896) = 1.447, p.=.030.)) This pattern continues

with Rycroft (real human male) and Rose (real human

female) with female participants’ scores statistically

significant while the male scores are not statistically

different (Female (D(2090) =1.312, p.= .064), Male

(D(1896) = 3.834, p.< .001)). When comparing the

both the Mid2-Low female avatars (Liliwen – Bailie),

the female participant scores are statistically

significant, and the male participants’ are not (Female

Observing the Uncanny Valley: Gender Differences in Perceptions of Avatar Uncanniness

213

(D(2090) = 2.166, p.< .001., Male(D(1896) = 1.699,

p.= .051.)).

The pattern identified in the preceding paragraph

is reversed for some of the avatars. For male avatars

(Macaw – Ira), the high realism male comparison

shows the male scores being statistically significant

and the females do not (Male(D(1896) = 3.834, p.<

.001), Female (D(2090) = 1.312, p.= .064)). This

continues with one of the Mid2-Low female avatars

(Bailie) to the real human male (Ira) comparison

where the distribution of the male scores is

statistically different and the female participant

scores are not (Male (D(1896) = 2.825, p.< .001),

Female (D(2090) = 1.444, p.= .031)). Again, the

comparison of the Mid2-Low male avatar (Leo) to the

high realism male (Ira) distributions are statistically

significant for male participants but not the female

participants (Male (D(1896) = 3.789, p.< .001),

Female (D(2090) = 1.553, p.= .016)). Lastly, we see

a statistically significant difference between the

distribution of scores for the Mid2-Low realism male

avatar (Leo) to the high realism female avatar (Emily)

for male participants but not for the females (Male

(D(1896) = 3.330, p.< .001), Female (D(2090)

=1.837,p.=.016)). The remaining comparisons were

not statistically significant for either gender(sex).

5 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSION

Our investigation into the impact of gender(sex)

considered if a participants’ gender(sex) affects the

perception of an avatar’s uncanniness ratings. Male

participants rated the higher realism avatars as

uncannier than all other avatars except for the Mid1

realism male avatar. This aligns to previous findings

where male participants were more sensitive to

uncanniness in human-like agents (Tinwell, 2014).

Of interest, the top four ranks for female

participants were populated by male avatar faces,

suggesting that these avatars may have triggered

negative responses for participants who identified as

female. Existing research on avatar faces features and

uncanniness suggest that avatars failing to display

empathy or reacting appropriately may lead to

assumptions of psychopathy in an avatar (Tinwell,

2014). As such, the critical dimensions of

uncanniness, such as threat avoidance and alignment

to terror management theory (MacDorman et al.,

2009) may be more enhanced in female participants.

It is also interesting that while there was some

consistency in the avatars ranked as most uncanny,

the same consensus was not present in those ranked

least uncanny, with female and male participants

responding differently. For both genders(sexes), the

avatars ranked as most uncanny were female,

although they were different avatars. These

differences led to further investigation of the

distribution of uncanniness ranks by participant

gender(sex) to reveal further insights.

From examination of the distribution of scores, we

see some interesting differences in the female and

male participant scores for each avatar. The real

humans and one of the Mid2-Low realism female

avatars scores exhibit a bi-modal distribution,

suggesting that the general opinion of these avatars is

divided. Additionally, despite both real humans

achieving high realism ranks, these avatars fall

around the middle of the uncanniness rankings. These

distributions were found to be statistically

significantly different when comparing the scores

when grouped by the participants’ gender(sex). These

differences may suggest that some participants were

convinced that these avatars were computer-

generated images as opposed to real humans, or

perhaps factors other than avatar realism contribute to

perceptions of uncanniness. Further, we see that the

one of the Mid2-Low realism female avatars (Bailie)

was ranked as the least realistic but ranked only 8th

on the uncanny scale, indicating that the avatar was

considered unrealistic but not uncanny. This supports

existing literature suggesting lower realism levels can

lead to avatars being perceived as less uncanny

(Tinwell, 2014).

Our findings highlight the importance of

gender(sex) in avatar design decisions due to the

impact of this variable on the perceptions of avatar

uncanniness. As previously identified, a detailed

consideration of the influence of gender(sex) in avatar

uncanniness perceptions is mostly missing in the

design decisions for avatar systems. Further, it is

evident from the literature that the unavoidable design

choice of gender(sex) for an avatar may have

underlying cues and expectations placed on them

based solely on their perceived gender(sex).

Together, the findings of the research provide key

insights into gender(sex) based perception of avatars.

Despite the significant contributions of this work,

it is not without some limitations. Firstly, there is a

lack of ethnic diversity in our surveys’ sample. The

primary ethnicities that completed this survey were of

White/Caucasian and Asian background, which may

lead to some bias in the interpretation of the data.

Secondly, the results cannot be extended to nonbinary

genders(sexes) due to small sample sizes. However,

this does present an avenue for future work. Lastly,

CHIRA 2022 - 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

214

while the participants in our study come from a wide

range of ages (18-87 years old (M= 34.82, SD=

11.52)), a restriction put in place by Mturk is that

participants must be at least 18 years old. Therefore,

the results presented in our study may not be

applicable to those under 18.

Another area of limitation relates to the avatars

themselves. There is a lack of diversity in the ten

avatars used in this study. The sample of avatars is

primarily of an Anglo-Saxon appearance with little

subjective difference in the facial features. Lastly, the

current study asks participants to consider the avatars

without the context of how they are used. We note

that perceptions might differ with context as

previously identified (Rosen, 2008). The complexity

of the ranking task necessitated the use of a minimal

avatar set. However, given that avatars, as virtual

representations of humans, could potentially reflect

the full diversity of the human form, it is arguable

how large a set would be required to be

representative. Thus, future work may seek to expand

the avatars evaluated to examine the differences in a

more diverse set.

Despite these limitations, the work presented here

has produced interesting insights into gender(sex)

differences in the perception of avatars and generates

several avenues for future research. First, the work

presented here has focused on perceptual effects of

the gender(sex) of both participants and avatars.

Future analysis may extend this to explore the

differences in the rankings associated with

perceptions of avatar-participant self-similarity and

avatar sex. An area for further analysis considers the

individual attributes of each of the ten avatars through

a gender(sex)-swapped lens to further explore

gender(sex) as a contributor to perceptions of

uncanniness. In summary, the work presented here

provides the basis for extending current

understanding of gender(sex) differences in the

perceptions of avatars.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by an Australian

Government Research Training Program (RTP)

Scholarship. The authors would like to thank Mr. Kim

Colyvas from the Statistical Support Services,

University of Newcastle, for his assistance with the

analysis of data for this manuscript.

REFERENCES

Adams, E. (2014). Fundamentals of game design. Pearson

Education.

Alexander, O., Rogers, M., Lambeth, W., Chiang, J., Ma,

W., Wang, C., & Debevec, P. (2017). The Digital Emily

Project: Achieving a Photoreal Digital Actor. USC

Institute for Creative Technologies.

amazon.com. (2017). amazon mechanical turk.

AppleInc. (2015). FaceShift. In (Version 2014.2.01)

FaceShift AG.

Baldwin, K. (2018). Virtual Avatars: Trans Experiences of

Ideal Selves Through Gaming. Markets, Globalization

& Development Review (MGDR), 3(3).

Battocchi, A., Pianesi, F., Goren-Bar, D. (2005). A first

evaluation study of a database of kinetic facial

expressions (dafex) Proceedings of the 7th international

conference on Multimodal interfaces, Trento, Italy.

Beltrán, M. (2013). The importance of the avatar gender in

training simulators based on virtual reality. Proceedings

of the 18th ACM conference on Innovation and

technology in computer science education,

Brunton, A., Bolkart, T., & Wuhrer, S. (2014). Multilinear

wavelets: A statistical shape space for human faces.

European Conference on Computer Vision,

Conover, W. J., & Iman, R. L. (1981). Rank

transformations as a bridge between parametric and

nonparametric statistics. The American Statistician,

35(3), 124-129.

Davison, A. J., Deutscher, J., & Reid, I. D. (2001).

Markerless motion capture of complex full-body

movement for character animation. In Computer

Animation and Simulation 2001 (pp. 3-14). Springer.

Fox, & Bailenson. (2009). Virtual virgins and vamps: The

effects of exposure to female characters’ sexualized

appearance and gaze in an immersive virtual

environment. Sex Roles, 61(3-4), 147-157.

Fox, J., Bailenson, J. N., & Tricase, L. (2013). The

embodiment of sexualized virtual selves: The Proteus

effect and experiences of self-objectification via

avatars. Comput Human Behav, 29(3), 930-938.

Lehdonvirta, M., Nagashima, Y., Lehdonvirta, V., & Baba,

A. (2012). The stoic male: How avatar gender affects

help-seeking behavior in an online game. Games and

Culture, 7(1), 29-47.

MacDorman, K. F., Green, R. D., Ho, C.-C., & Koch, C. T.

(2009). Too real for comfort? Uncanny responses to

computer generated faces. Comput Human Behav,

25(3), 695-710.

Mantiuk, R. K., Tomaszewska, A., & Mantiuk, R. (2012).

Comparison of four subjective methods for image

quality assessment. Computer Graphics Forum, 31(8),

2478-2491.

Metrics, I. (2018).

Faceware. In (Version 3.1) Faceware

Tech.

Mori, M., MacDorman, K. F., & Kageki, N. (2012). The

uncanny valley [from the field]. IEEE Robotics &

Automation Magazine, 19(2), 98-100.

Observing the Uncanny Valley: Gender Differences in Perceptions of Avatar Uncanniness

215

Nao4288, n. (2013). Female Facial Animation ver 1.0 (No

Sound) [YouTube Video]. https://tinyurl.com/yc6k6

e3k

Patel, H., & MacDorman, K. F. (2015). Sending an avatar

to do a human's job: Compliance with authority persists

despite the uncanny valley. Presence, 24(1), 1-23.

Rosen, K. R. (2008). The history of medical simulation.

Journal of critical care, 23(2), 157-166.

Saito, S., Wei, L., Hu, L., Nagano, K., & Li, H. (2017).

Photorealistic facial texture inference using deep neural

networks. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on

Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu,

Hawaii, United States.

Seyama, J. i., & Nagayama, R. S. (2007). The uncanny

valley: Effect of realism on the impression of artificial

human faces. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual

Environments, 16(4), 337-351.

Seymour, M., Riemer, K., & Kay, J. (2018). Actors, avatars

and agents: potentials and implications of natural face

technology for the creation of realistic visual presence.

Journal of the Association for Information Systems,

19(10), 4.

Stephenson, N. (1993). Snow Crash. Bantam Books.

Stumpf, S., Peters, A., Bardzell, S., Burnett, M., Busse, D.,

Cauchard, J., & Churchill, E. (2020). Gender-inclusive

HCI research and design: A conceptual review.

Foundations and Trends in Human–Computer

Interaction, 13(1), 1-69.

Tewari, A., Zollhofer, M., Kim, H., Garrido, P., Bernard,

F., Perez, P., & Theobalt, C. (2017). Mofa: Model-

based deep convolutional face autoencoder for

unsupervised monocular reconstruction. Proceedings of

the IEEE International Conference on Computer

Vision, Italy.

Thies, J., Zollhöfer, M., Nießner, M., Valgaerts, L.,

Stamminger, M., & Theobalt, C. (2015). Real-time

expression transfer for facial reenactment. ACM Trans.

Graph., 34(6), 183:181-183:114.

Tinwell, A. (2014). The uncanny valley in games and

animation. AK Peters/CRC Press.

von der Pahlen, J., Jimenez, J., Danvoye, E., Debevec, P.,

Fyffe, G., & Alexander, O. (2014). Digital ira and

beyond: creating real-time photoreal digital actors.

ACM SIGGRAPH 2014 Courses,

Wang, C.-C., & Yeh, W.-J. (2013). Avatars with sex appeal

as pedagogical agents: Attractiveness, trustworthiness,

expertise, and gender differences. Journal of

Educational Computing Research, 48(4), 403-429.

Winkler, S. (2009). On the properties of subjective ratings

in video quality experiments. Quality of Multimedia

Experience, 2009. QoMEx 2009. International

Workshop on Quality of Multimedia Experience, USA.

Yee, N., & Bailenson, J. (2007). The Proteus effect: The

effect of transformed self-representation on behavior.

Human communication research, 33

(3), 271-290.

CHIRA 2022 - 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

216