The Role of Third-parties in Sustainable Supply Chain Management:

A Systematic Literature Review

Alexander Neske

1

, H.-Christian Brauweiler

2

, Ilona Bordianu

3

,

Nataliia Anashkina

4

and Aida Yerimpasheva

5

1

Scheer GmbH, Düsseldorf, Germany

2

WHZ Westsächsische Hochschule Zwickau (Univ. of Applied Sciences), Zwickau, Germany

3

KAFU Kazakh-American Free University, Ust-Kamenogorsk, Kazakhstan

4

Ural State University of Railway Transport, Yekaterinburg, Russia

5

Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Almaty, Kazakhstan

Keywords: Sustainable Supply Chain Management, third-parties, social issues, environmental issues, literature review,

future research.

Abstract: This paper investigates the role of third-parties (e.g. NGOs, auditing and certification organizations etc.) in

Sustainable Supply Chain Management with respect to managing environmental and social sustainability

utilizing the Systematic Literature Review methodology. The paper identifies third-parties as Drivers,

Facilitators and Inspectors, each contributing different strategies to the Sustainable Supply Chain

Management. In relation to the needed resources of firms in Sustainable Supply Chain Management third-

parties are active participants in providing these resources. Based on the findings, further research

opportunities are provided for further investigate the literature from this novel perspective. The novelty in

this paper lies in the used perspective on third-parties as actors in Sustainable Supply Chain Management.

1 INTRODUCTION

The competitive advantage of firms is not only about

themselves, but also relies on their supply chains. In

the face of sustainability, sustainable supply chain

management (SSCM) has become a key role

(Seuring, 2008). Nevertheless, the interdependencies

in sustainability are challenging for firms, in

particular developing a successful SSCM. In turn,

we see that no firm is able to tackle these challenges

alone (Mohrman, 2010; Wilhelm, 2016). To address

this, research in sustainable supply chain

management has focused on strategies firms employ

to develop a successful SSCM (Montabon, 2016).

Besides relying on internal mechanisms, the food

company Mars parallel began working with various

actors to achieve its sustainability goals in its supply

chain (Ionova, 2018).

So far, the literature lacks on an holistic

overview and remains unclear in which way and to

what extend these different actors (following called

as third-parties) enhance the sustainable supply

chain management of firms. It is thus important to

narrow down and focus on third-parties. Looking at

third-parties is interesting and necessary for various

reasons. First, third-parties own knowledge and

expertise firms might not have. This could be on the

one hand external knowledge like technical know-

how on processes for auditing or controlling

sustainability-related processes. On the other hand,

the knowledge could be network-related in terms of

providing access to networks with different partners

like other NGOs at the sourcing point or bringing

together actors from different regions and with

different interests at e.g. conferences. Second, as

third-parties could have no contractual relationship

to firms, they have an intermediary position and are

not influenced by the firms. This relationship brings

the advantage that third-parties have a high degree

of freedom in e.g. criticizing firms. Therefore, the

aim of this research is to investigate the role of third-

parties in sustainable supply chain management

literature. In particular, we want to answer two

research questions: 1) Which role do third-parties

play in sustainable supply chain management and

how do they contribute to SSCM? 2) What research

opportunities arise from that? For that end, we rely

Neske, A., Brauweiler, H., Bordianu, I., Anashkina, N. and Yerimpasheva, A.

The Role of Third-parties in Sustainable Supply Chain Management: A Systematic Literature Review.

DOI: 10.5220/0011581900003527

In Proceedings of the 1st International Scientific and Practical Conference on Transport: Logistics, Construction, Maintenance, Management (TLC2M 2022), pages 215-223

ISBN: 978-989-758-606-4

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

215

on the Systematic Literature Review to answer the

research objectives.

The remainder of the article is organized as

follows: In the Materials and Method section, we

introduce the understanding of who a third-party

from our point of view is, placing it in context of

previous literature. Following, we outline the

Systematic Literature methodology and our

procedure. The Results and Discussion section

consists of three parts. First, we provide descriptives

from our analysis. Second, we outline the roles of

third-parties in SSCM. Third, we map possible

future research opportunities. The paper ends with a

conclusion.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Understanding Who Is a

Third-party

For understanding, who is a possible third-party we

following give a brief review. Academic literature

calls for an inclusion of third-parties in SSCM

research (Pagell, 2014) and stresses the supportive

character of divergent stakeholders (Gimenez,

2012). While some stakeholders are more interested

in social issues, others focus their interest on

ecological issues (Pagell, 2014). While some of

these stakeholders draw their attention on firms

solely, others exerting pressure on firms or offering

firms their specific resources (Gimenez and

Tachizawa, 2012; Rodríguez, 2016; Ciliberti, 2011).

Meaning that, third-parties are organizations like

NGOs, competitors, like firms from the same

industry, or standardization organizations.

2.2 Systematic Literature Review

For answering the research objectives we apply the

Systematic Literature Review (SLR) methodology.

From our point of view it is the best way of getting a

first impression of the research landscape as it “[…]

locates existing studies, selects and evaluates

contributions, analyses and synthesizes data, and

reports the evidence in such a way that allows

reasonably clear conclusions to be reached about

what is and is not known.” (Denyer, 2009) From our

point of view the SLR offers two advantages,

namely 1) consolidating existing research in a field

and 2) providing potentially gaps in the literature

from which research opportunities can be adressed

(Tranfield, 2003). To meet the need for identifying

relevant literature for our research objectives we

developed quality- and content-related inclusion and

exclusion criteria as shown in the table below.

After having defined inclusion and exclusion

criteria we sort out selected keywords to build up the

search string. The keywords are combined with

Boolean connectors (AND, OR) and are refined with

asterisk wildcards (*). As the purpose of this SLR is

to get an overview of the research landscape we built

a rather inclusive search string. This in turn reduces

the sampling bias proposed by (Durach, 2017). After

Table 1: Search Criteria.

Inclusion/Exclusion criteria Rationale

Quality

Peer reviewed articles in journals with impact

factor ≥ 1.0 in the Journal Citation Report 2017

and if not applicable using Academic Journal

Guide 2018 ≥ 3.

To ensure minimum quality level and reducing sampling

bias (Durach, 2017; Nurunnabi, 2018; Schorsch, 2017).

Content

Review scope is on articles published since 1987. First introduction of “Sustainability”-definition by

Brundtland Report (Brundtland, 1987).

Article language is in English.

English is the research language and ensures accessibility

and comparability of results.

Sustainability includes at least ecological or social

dimension.

Articles exclusively dealing with economic sustainability

are excluded.

Third-party and their contribution.

Based on Clarkson (1995) secondary stakeholder.

Furthermore, the third-party needs to have a contribution

in the studies’ result part.

Examining inter-organizational view.

Publications should look at the supply chain from an inter-

organizations view rather than from an intra-organizations

(

internal

)

view as this

p

a

p

er focuses on su

pp

l

y

chains.

Original Research (i.e., literature reviews,

editorials, and meta-theories were excluded).

This paper is looking for original theoretical and empirical

contributions as they shed new light on research and are

more

p

recise and s

p

ecific in terms of their unit of anal

y

sis.

TLC2M 2022 - INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC AND PRACTICAL CONFERENCE TLC2M TRANSPORT: LOGISTICS,

CONSTRUCTION, MAINTENANCE, MANAGEMENT

216

constructed a first draft of the search string we

discussed it with experts and other scholars and

refined the search string accordingly. The final

search string is divided into categories which reflect

our research objectives: third-party type,

sustainability dimension and supply chain. For

identifying business related literature, we used the

Business Source Complete database by EBSCO.

Fields used for the search were: publication title,

abstract and descriptors of publications in the

database as well as year of publication between 1987

and 2018 (December). Following, we got 4,336 hits.

A key step in answering our research objectives was

the screening process initiated by the application of

the minimum quality criteria. Based on the abstract,

the 2,681 passed publications were following

evaluated using a coding sheet. We evaluated the

publications abstracts in a rather inclusive manner

leading to 94 hits. Finally, we analysed the full paper

leading to 36 publications meeting our criteria.

During the evaluation we excluded publications due

to various reasons. A huge pile of research dealt

with either an intra-organizational view with no

indication of regarding the third-party in relation to

the supply chain or the publication investigated the

collaboration in a classical manner (buyer-supplier)

with no indication of a third-party. This in turn,

supports our arguments that research so far mostly

looked at classical relationships of buyers and

suppliers. However, to further conduct the extraction

and synthesis of the literature we used a coding

scheme. During the analyzation and extraction the

coding scheme was adjusted and refined to meet the

level of detail. To provide a holistic view on the

literature we categorized the publications according

to year, journal, methodology, theoretical lens, third-

party role and third-party activity, and sustainability

focus (environmental or social).

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Descriptive Results

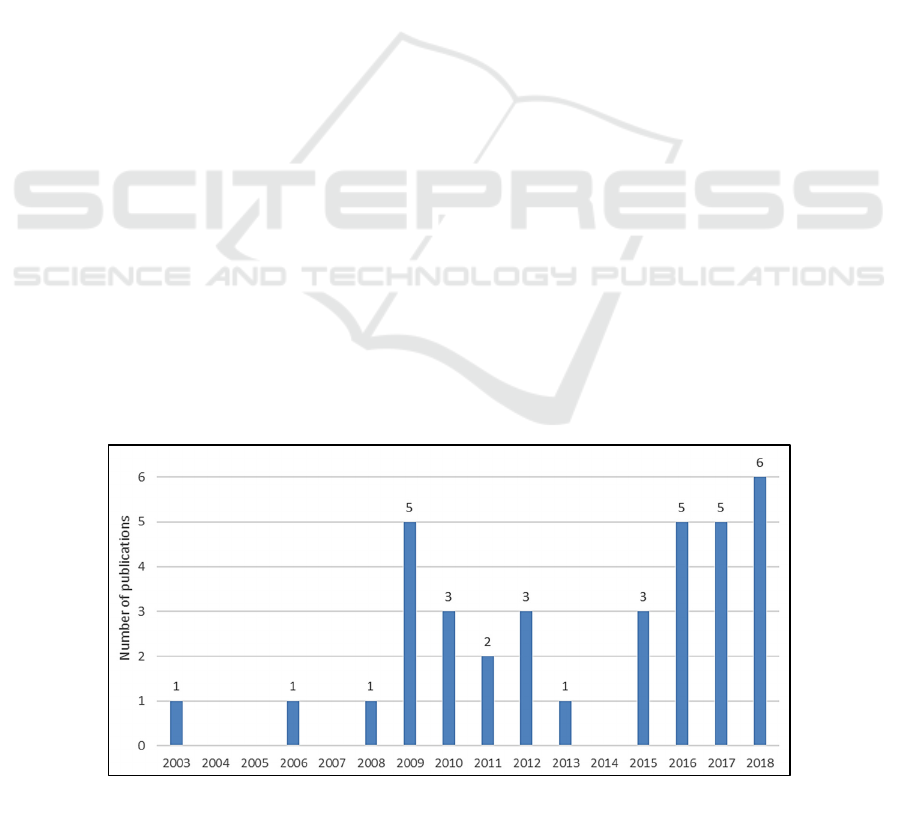

The first publications appeared in 2003. This is

interesting as we expected earlier publications as the

Brundtland Commission introduced a first definition

of sustainability in 1987, leading to a wide ranging

utilization in academia and practice. After only two

more publications in 2006 and 2008, the

publications show a rash in 2009. The following

years are characterized by a steady decline of

publications until 2014. Beginning in 2015 the

number of publications raised again with a top in

2018 with 6 publications. We assume that the Rana

Plaza Collapse in 2013 has led to an increase in

publications, which shows up with a time delay.

Despite the late start of publications address the

research objective we see a wavelike increase of

publications over the years so far. From our point of

view this signals the interest in the field in particular

against the background that over half of the

publications are published since 2015.

For us it was interesting which journals and

respective academic disciplines had an interest in the

topic. For that we calculated the number of

publications published by the respective journal. We

see quite a high interest and outcome of the top

seven journals as they contribute half of the

publications. Interestingly, the remaining 18

publications all come from different journals.

However, as the publications are distributed across a

wide range of journals we understand that as the

Figure 1: Publications Over Time.

The Role of Third-parties in Sustainable Supply Chain Management: A Systematic Literature Review

217

research topic has attracted a variety of research

disciplines.

Interestingly, approximately all publications (34

of 36) were empirical. The remaining publications

were mathematical and conceptual. From the 34

empirical publications only five were quantitative in

nature whereas 24 were qualitative case studies.

Two were mixed methods and the resulting three

were qualitative survey, action research and design

science. In particular, the case studies show that the

topic is still in an early phase as academia still

focuses on understanding the topic.

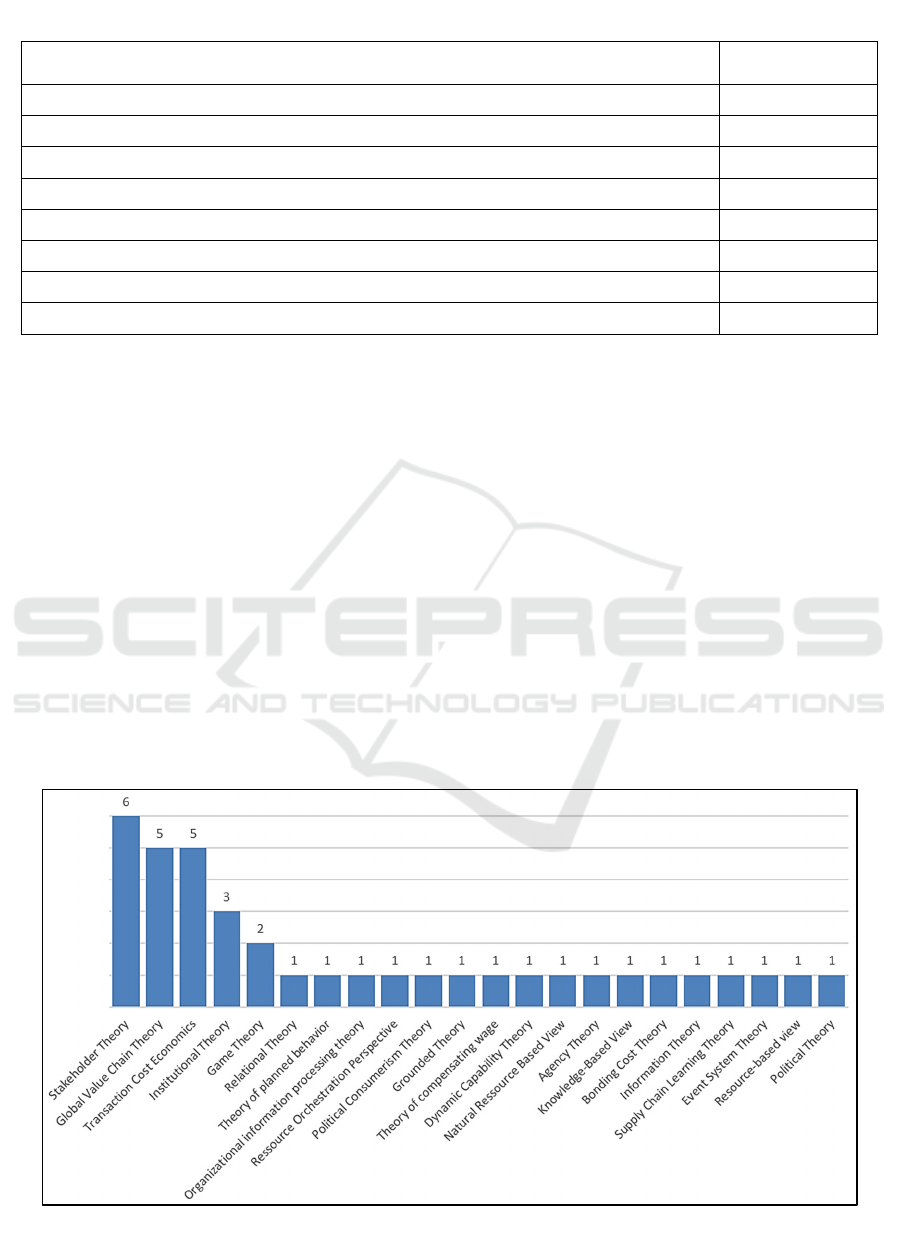

Regarding the theory utilization we see that some

of the papers do not use any theory for the

investigation or explanation of their findings, while

others use more than one theory. However, we found

out that some theories are preferentially used. In

particular, we see that Stakeholder Theory has been

used most often. From our point of view, the

Stakeholder Theory has a long standing history and

utilization. It provides assumptions which could be

used from various perspectives and therefore

provides the basis for approaching a new topic. In

particular, it can be used to explain the pressures

from third-parties on firms on the one hand and the

collaboration of firms and third-parties on the other

hand. Same holds true for the Transaction Cost

Economics and Global Value Chain Theory, and the

Institutional Theory. Our impression, that academia

make use of a view macro theories is shown by the

Stakeholder Theory, Global Value Chain Theory,

Transaction Cost Economics, and Institutional

Theory, responsible for almost 50% of the theories

used in publications. However, it shows also that the

Figure 2: Theory Utilization

Table 2: Distribution of publications in journals.

Journal Number of

publications

Journal of Business Ethics 4

Business Strategy and the Environment 3

Journal of Cleaner Production 3

Regulation & Governance 2

International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 2

International Journal of Operations and Production Management 2

International Journal of Production Economics 2

Others 18

TLC2M 2022 - INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC AND PRACTICAL CONFERENCE TLC2M TRANSPORT: LOGISTICS,

CONSTRUCTION, MAINTENANCE, MANAGEMENT

218

topic has attracted a variety of disciplines using

different theories as their prevailing theory lense on

the topic.

3.2 Roles of Third-Parties in

Sustainable Supply Chain

Management

In this section, we present the roles third-parties

inherit. For categorization we use the classification

of Liu et al. (2018). In their work, they developed

the roles based on strategies used for supplier

development for sustainability. The roles are

grouped in Drivers, Facilitators, Inspectors. The

rationale for using this categorization is threefold.

First, with the classification we are able to

differentiate the relationships of firms and third-

parties based on the third-parties’ contributions.

Second, this offers a first arrangement of the

literature while on the one hand is clustered wide

enough but still leaves room for further clustering,

whether it is within the roles or extending them in

breadth. Third, using the categorization we can build

on first empirical findings and test the categorization

against a new perspective.

During the course of analyzation we applied a

categorization strategy to propose and sort the roles

of third-parties based on their contributions.

Therefore, we iteratively 1) identified the activities

of third-parties on SSCM, 2) Propose higher clusters

which relate to the roles, 3) Analyze the quotes in

the publications to categorize the roles and their

contributions, 4) Refine the roles and their

contributions.

However, in the following we present the roles.

First, we explain them in brief, followed by

reporting the contributions they inherit on SSCM.

Due to the limitation of space we only describe some

cases in more detail as the objective is on providing

an overview of the roles and their respective

activities on a high level.

3.3 Drivers

Liu et al. (2018) describe drivers as third-parties that

pressure and incentivize firms or somehow initiate

sustainable practices. In this sense, they shape and

co-design firms sustainability objectives. Drivers are

mission driven, as they have oftentimes direct access

to firms decision makers (Liu et al., 2018).

Our findings support this view, as third-parties

perform activities such as pressuring or promoting

SSCM. On the one hand, third-parties like NGOs,

media or industry partnerships pressure firms to

consider sustainability-related issues like carbon

emissions in supply chains or social issues at

supplier sites (Liu, 2018; Park-Poaps, 2010; Mani,

2018; Reuter, 2010). On the other hand we see that

e.g. governments promoting the collaboration of

firms and their suppliers (Cheung, 2009).

3.4 Facilitators

Facilitators provide firms with knowledge and

resources for e.g. capacity building. They engage

with firms while enhancing the firms’

implementation and scaling for SSCM. With that

they diffuse sustainability practices of supply chain

member (Liu, 2018).

Our findings show that a portfolio of diverse

contributions characterizes facilitators: sharing

information, providing platforms, engaging further

parties, allocating social funds, providing financial

support, and supporting operations.

Sharing information is arguably the most

common investigated activity of third-parties and

subsumes various contributions regarding the

exchange of knowledge. In particular, third-parties

1) educate and train firms or suppliers (Liu, 2018;

Cheung, 2009; Benstead, 2018; Gong, 2018; Bek,

2017; Huq, 2016). For example in the case of

Loconto (2015) the third-party educates the

suppliers on how to comply with standards such as

the Rainforest Alliance or Fairtrade on the

ecological side. On the other hand, the third-party

educates and trains the supplier on agricultural

working conditions practices. 2) provide frameworks

that firms could use to facilitate their SSCM

(Delmas, 2009; Bek, 2017; Müller, 2009; Sinkovics,

2016; Boer, 2003; Cheung, 2009). For example,

Canzaniello et al. (2017) and Nadvi and Raj-

Reichert (2015) show that third-parties provide

surveys and tools for the enhancement of

sustainability. In line with that, Ciliberti et al. (2009)

show that third-parties provide frameworks for self-

assessments against sustainability standards. Nadvi

and Raj-Reichert (2015) show that third-parties can

replace the myriad of standards and consolidate

them to on industry-wide one for suppliers. 3)

provide information on supplier performance leading

to higher transparency (Meinlschmidt, 2018;

Plambeck, 2012; Canzaniello, 2017; Müller, 2009).

In this sense, the third-party uses collected

information to provide it to the firms. For example

Busse et al. (2017) show that third-parties provide

information on working conditions at supplier sites.

4) provide non-directed information. In the case of

Cheung et al. (2009) the third-party provides

The Role of Third-parties in Sustainable Supply Chain Management: A Systematic Literature Review

219

information for both firms and suppliers while in

Hartlieb and Jones (2009) the third-party provides a

label as stamp of approval downstream the supply

chain. 5) consulting was the least found contribution

of third-parties. In the case of Benstead et al. (2018)

the third-party provides consultancy to firms to

develop a labor issue risk matrix for sourcing

locations.

A further contribution of third-parties to SSCM

is providing platforms in form of conferences,

meetings, workshops, and websites (Xu, 2018;

Gong, 2018; van Hoof, 2013; Wetterberg, 2011;

Canzaniello, 2017; Kumar, 2006). While providing

platforms the third-party helps to meet and exchange

of suppliers, firms and other actors Cheung et al.

(2009). In the case of Benstead et al. (2018) the

third-party provides workshops and meetings which

enables the participants to exchange information on

social best practices.

Engaging further parties is a contribution of

third-parties as they coordinating further actors. In

the case of Huq et al. (2016) and Nadvi and Raj-

Reichert (2015) the third-party engages a further

party to audit suppliers. In line with that, Everett et

al. (2008) shows a similar contribution as an NGO

engages a further party to monitor the firms

suppliers.

Third-parties allocating social funds provide

resources to specific regions for social change.

Loconto (2015), Lund-Thomsen and Nadvi (2010)

and Ciliberti et al. (2009) show how a third-party

allocates social funds for development projects at

supplier regions. A similar picture emerges for

Muller et al. (2012) as a non-profit organization

allocates social funds of firms for charity projects at

supplier regions.

Quite similar to the above mentioned is

providing financial support. The difference here lies

in the type of resource as in this case the third-party

provides financial resources as in the case of Cheung

et al. (2009) and van Hoof and Lyon (2013) showing

that governments or non-profit organizations take

over operational costs between suppliers and firms.

It is interesting to see that in only one case third-

parties support operations. Only Kumar and

Malegeant (2006) providing evidence where a third-

party supports operations by collecting and

transporting used shoes from the customer to the

firm.

3.5 Inspectors

Inspectors are third-parties that if at all have a weak

relationship to firms. The relationship of inspectors

to firms is neutral as they perform mostly activities

like assessment and monitoring of sustainability

(Liu, 2018).

Our findings support this view, as our results

show that inspectors monitor and audit suppliers

sustainability (Plambeck, 2012; Wetterberg, 2011;

Meinlschmidt, 2018; Müller, 2009; Lund-Thomsen,

2010; Wilhelm, 2016; Sinkovics, 2016; Bair, 2017;

Ciliberti, 2009; Kourula, 2016; Huq, 2016; Zhang,

2017; Liu, 2018; Benstead, 2018).

One finding somehow deviates from the spot

testing as in the case of Oka (2016) a labour union

permanently monitors the suppliers social

sustainability performance.

3.6 Where to Go from Here: Providing

a Future Research Agenda

Throughout the course of research, we identified

several research opportunities. The aim of this

chapter is to give some ideas for further research as

a starting point. The ideas are rather loosely

assembled with no claim on completeness.

First, expanding and balancing research methods

applied. Looking at the research methods applied,

we call for more qualitative research conceptual

wise as this can provide new ideas which than can

be proofed. In line with this, we furthermore call for

more quantitative and mixed-method research to

prove the qualitative constructs developed so far.

This supports the models developed out of particular

research settings and enables to test against a

broader perspective. From our point of view, this

leads to overcoming the barrier of young research

and leading to maturity in SSCM research.

Second, expanding and balancing theories

applied. It is striking that quite some papers have a

rather explanatory or descriptive character. In line

with expanding research methods, we call for the

expansion of the theories used or even develop new

ones, following a grounded theory approach. From

our point of view, this is valuable as it leads to new

findings for the coming decade of sustainable

transformation. In particular, applying a grounded

theory approach gives the possibility to develop an

own understanding instead of relying or mixing

popular lenses from other disciplines.

Third, expanding the understanding of third-

parties in SSCM. Further research can extend the

understanding of the roles we provide in breadth and

depth. As we saw, third-parties could be seen in a

lifecycle model. Therefore, it could be interesting to

see if different factors leading to a third-party being

a driver. For example, it could be interesting to see

TLC2M 2022 - INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC AND PRACTICAL CONFERENCE TLC2M TRANSPORT: LOGISTICS,

CONSTRUCTION, MAINTENANCE, MANAGEMENT

220

whether the role of a third-party is contingency

dependent. This would not only increase the

understanding content-related but also extend the

theory utilization. Furthermore, deepen the

understanding which factors lead to the utilization of

a third-party as a facilitator. Are there reasons

leading to a specific utilization of a third-party or a

mix of different third-parties? In addition, it could be

interesting to further investigate the activities third-

parties do. For example, it could be interesting to see

whether different activities lead to better outcomes

of SSCM. For this, a quantitative and comparative

analysis would be helpful to see possible

differences. In line with that is the question, if a

bundle of activities is better instead of on relying to

just one. Regarding the roles third-parties inherit, it

could be interesting to see if the roles shape the

firms internal and external management and if so,

how. By addressing firms, can it be that third-parties

switching roles or inherit different roles at the same

time? For example, while providing knowledge to

the firm is it still possible that third-parties

accurately monitor the firms or are they influenced

by having a relationship with the firm already? In

particular, this investigation could be monitored with

a longitudinal study to see changes over time.

4 CONCLUSION

In this paper, utilizing the systematic literature

review we investigated the roles of third-parties in

SSCM. Based on that, we outlined possible future

research avenues. Our findings show that third-

parties have different roles in contributing to SSCM.

The paper advances research in sustainable supply

chain management in various ways. First, we

showed that third-parties influence SSCM according

to their role differently. Third-parties as Drivers

initiate SSCM activities, while Facilitators work

specifically on enhancing the SSCM in a way that

they cooperate with firms or provide cooperation

platforms for supply chain members. Third-parties

as Inspectors monitor the sustainability performance

of the SSCM activities or performance. Second, with

our investigation we show that third-parties as

“others” than buyers and suppliers are active

participants in SSCM. This verifies prior

observations (Pagell, 2009). Third, based on our

findings we map future research opportunities,

which are guided by the paper itself, and in

particular through our specific, non-exhaustive,

future research opportunities.

However, there are limitations in our study due

to the utilization of the systematic literature review.

First, although we applied a rather broad search

string to retrieve potential literature we still could

have missed some. This either could be caused by

missing keywords or because the specific literature

is not listed in the database we used. Second,

although we used a rather broad research string to

widen the sampling, we could have faced some

sampling bias. For overcoming possible limitations

we call for further research on third-parties in

SSCM.

Besides the academic contribution, we also offer

managerial insights. For managers it could be useful

to differentiate third-parties in their contributions on

SSCM. In particular, this could help to specifically

pick third-parties for e.g. collaborations or in

supporting the SSCM in monitoring suppliers. The

picking process can be supported in specifying the

needed resources third-parties potentially provide.

With that, firms can professionalize their stakeholder

management in terms of SSCM. Further, from a

third-party perspective our findings can help to

clarify their role they want to play. With that, third-

parties can professionalize their strategic alignment,

whether they want to be a Driver, Facilitator or

Inspector. In clarifying their role and possible

separate them they clearly can rely on their role and

do not need to worry to sit between chairs meaning

their e.g. supporters in society turn away as the

third-party lose their strategic alignment.

However, with our research we provided a new

perspective on the literature on actors in SSCM and

showed that third-parties are active participants,

playing a specific role.

REFERENCES

Bair, J., 2017. Contextualising compliance: hybrid

governance in global value chains. New political

economy. 22. 2. pp. 169-185.

Bek, D., Binns, T., Blokker, T., Mcewan, C., Hughes, A.,

2017. A High Road to Sustainability? Wildflower

Harvesting, Ethical Trade and Social Upgrading in

South Africa's Western Cape. Journal of Agrarian

Change, l. 17. 3, pp. 459-479.

Benstead, A. V., Hendry, L. C., Stevenson, M., 2018.

Horizontal collaboration in response to modern

slavery legislation. International Journal of

Operations & Production Management. 38. 12. pp.

2286–2312.

Boer, J. de., 2003. Sustainability labelling schemes: the

logic of their claims and their functions for

The Role of Third-parties in Sustainable Supply Chain Management: A Systematic Literature Review

221

stakeholders. Business Strategy and the Environment.

12. 4. pp. 254-264.

Brundtland, G. H., 1987. Our Common Future, World

Commission on Environment and Development,

Brussels.

Busse, C., Schleper, M. C., Weilenmann, J., Wagner, S.

M., 2017. Extending the supply chain visibility

boundary: Utilizing stakeholders for identifying

supply chain sustainability risks. International Journal

of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management. 47.

1. pp. 18-40.

Canzaniello, A., Hartmann, E., Fifka, M. S., 2017, Intra-

industry strategic alliances for managing

sustainability-related supplier risks. International

Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics

Management. 47. 5. pp. 387-409.

Cheung, D. K. K., Welford, R. J., Hills, P. R., 2009. CSR

and the environment. Business supply chain

partnerships in Hong Kong and PRDR, China,

Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental

Management. 16. 5, pp. 250-263.

Ciliberti, F., Groot, G. de, Haan, J. de and Pontrandolfo,

P., 2009. Codes to coordinate supply chains. SMEs'

experiences with SA8000. Supply Chain Management:

An International Journal. 14. 2, pp. 117-127.

Ciliberti, F., Haan, J. de, Groot, G. de and Pontrandolfo,

P., 2011. CSR codes and the principal-agent problem

in supply chains. Four case studies. Journal of Cleaner

Production. 19. 8. pp. 885-894.

Clarkson, M. B. E., 1995. A Stakeholder Framework for

Analyzing and Evaluating Corporate Social

Performance. The Academy of Management Review.

20. 1. pp. 92-117.

Delmas, M., Montiel, I., 2009. Greening the Supply

Chain: When Is Customer Pressure Effective? Journal

of Economics & Management Strategy. 18. 1. pp. 171-

201.

Denyer, D., Tranfield, D., 2009. Producing a systematic

review. The Sage handbook of organizational research

methods. pp. 671–689.

Durach, C. F., Kembro, J., Wieland, A., 2017. A New

Paradigm for Systematic Literature Reviews in Supply

Chain Management. Journal of Supply Chain

Management. 53. 4. pp. 67-85.

Everett, J. S., NEU, D., Martinez, D., 2008. Multi-

Stakeholder Labour Monitoring Organizations:

Egoists, Instrumentalists, or Moralists? Journal of

Business Ethics. 81. 1. pp. 117–142.

Gimenez, C., Tachizawa, E. M., 2012. Extending

sustainability to suppliers: a systematic literature

review. Supply Chain Management: An International

Journal. 17. 5. pp. 531-543.

Gong, Y., Jia, F., Brown, S., Koh, L., 2018. Supply chain

learning of sustainability in multi-tier supply chains.

International Journal of Operations and Production

Management. 38. 4. pp. 1061-1090.

Hartlieb, S., Jones, B., 2009. Humanising Business

Through Ethical Labelling. Progress and Paradoxes in

the UK. Journal of Business Ethics. 88. 3. pp. 583-

600.

Huq, F. A., Chowdhury, I. N., Klassen, R. D., 2016. Social

management capabilities of multinational buying firms

and their emerging market suppliers. An exploratory

study of the clothing industry. Journal of Operations

Management. 46. pp. 19-37.

Ionova, A., 2018. Mars aims to tackle broken cocoa model

with new sustainability scheme – Reuters.

https://www.reuters.com/.

Kourula, A., Delalieux, G., 2016. The Micro-level

Foundations and Dynamics of Political Corporate

Social Responsibility. Hegemony and Passive

Revolution through Civil Society. Journal of Business

Ethics. 135. 4. pp. 769-785.

Kumar, S., Malegeant, P., 2006, Strategic alliance in a

closed-loop supply chain, a case of manufacturer and

eco-non-profit organization. Technovation. 26. 10. pp.

1127-1135.

Liu, L., Zhang, M., Hendry, L. C., Bu, M. Wang, S., 2018.

Supplier Development Practices for Sustainability: A

Multi-Stakeholder Perspective. Business Strategy and

the Environment. 27, pp. 100-116.

Loconto, A., 2015. Assembling governance: the role of

standards in the Tanzanian tea industry. Journal of

Cleaner Production. 107, pp. 64-73.

Lund-Thomsen, P., Nadvi, K., 2010. Clusters, Chains and

Compliance. Corporate Social Responsibility and

Governance in Football Manufacturing in South Asia.

Journal of Business Ethics. 93. pp. 201-222.

Mani, V., Gunasekaran, A., 2018. Four forces of supply

chain social sustainability adoption in emerging

economies. International Journal of Production

Economics. 199. pp. 150-161.

Meinlschmidt, J., Schleper, M. C., Foerstl, K., 2018.

Tackling the sustainability iceberg, International

Journal of Operations & Production Management. 38.

10, pp. 1888-1914.

Mohrman, S. A., Worley, C. G., 2010. The Organizational

Sustainability Journey: Introduction to the Special

Issue. Organizational Dynamics. 39. 4. pp. 289-356.

Montabon, F., Pagell, M., Wu, Z., 2016. Making

Sustainability Sustainable. Journal of Supply Chain

Management. 52. 2. pp. 11-27.

Muller, C., Vermeulen, W. J. V., Glasbergen, P., 2012.

Pushing or Sharing as Value-driven Strategies for

Societal Change in Global Supply Chains. Two Case

Studies in the British-South African Fresh Fruit

Supply Chain. Business Strategy and the Environment.

21. 2. pp. 127-140.

Müller, C., Vermeulen, W. J. V., Glasbergen, P., 2009.

Perceptions on the demand side and realities on the

supply side. A study of the South African table grape

export industry. Sustainable Development. 17. 5. pp.

295-310.

Nadvi, K., Raj-Reichert, G., 2015. Governing health and

safety at lower tiers of the computer industry global

value chain. Regulation & Governance. 9. 3. pp. 243-

258.

Nurunnabi, M., Alfakhri, Y., Alfakhri, D. H., 2018.

Consumer perceptions and corporate social

responsibility. What we know so far. International

TLC2M 2022 - INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC AND PRACTICAL CONFERENCE TLC2M TRANSPORT: LOGISTICS,

CONSTRUCTION, MAINTENANCE, MANAGEMENT

222

Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing. 15. 2. pp.

161-187.

Oka, C., 2016. Improving Working Conditions in Garment

Supply Chains: The Role of Unions in Cambodia.

British Journal of Industrial Relations. 54. 3. pp. 647-

672.

Pagell, M., Shevchenko, A., 2014. Why Research in

Sustainable Supply Chain Management Should Have

no Future. Journal of Supply Chain Management. 50.

1. pp. 44-55.

Pagell, M., Wu, Z., 2009. BUILDING A MORE

COMPLETE THEORY OF SUSTAINABLE

SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT USING CASE

STUDIES OF 10 EXEMPLARS. Journal of Supply

Chain Management. 2. 45. pp. 37-56.

Park-Poaps, H., Rees, K, 2010. Stakeholder Forces of

Socially Responsible Supply Chain Management

Orientation. Journal of Business Ethics. 92. 2. pp. 305-

322.

Plambeck, E., Lee, H. L., Yatsko, P., 2012. Improving

Environmental Performance in Your Chinese Supply

Chain. MIT Sloan Management Review. 53. 2. pp. 43-

51.

Reuter, C., Foerstl, K., Hartmann, E., Blome, C., 2010.

Sustainable Global Supplier Management: The Role of

Dynamic Capabilities in Achieving Competitive

Advantage. Journal of Supply Chain Management. 46.

2. pp. 45-63.

Rodríguez, J. A., Giménez Thomsen, C., Arenas, D.,

Pagell, M., 2016. NGOs' Initiatives to Enhance Social

Sustainability in the Supply Chain. Poverty

Alleviation through Supplier Development Programs.

Journal of Supply Chain Management. 52. 3. pp. 83-

108.

Schorsch, T., Wallenburg, C. M., Wieland, A. 2017. The

human factor in SCM: Introducing a Meta-theory of

Behavioral Supply Chain Management. International

Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics

Management. 47. 4. pp. 238-262.

Seuring, S., Müller, M. 2008. From a literature review to a

conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain

management. Journal of Cleaner Production. 16. 15.

pp. 1699-1710.

Sinkovics, N., Hoque, S. F. and Sinkovics, R. R. 2016.

Rana Plaza collapse aftermath. Are CSR compliance

and auditing pressures effective? Accounting, Auditing

& Accountability Journal. 29. 4. pp. 617-649.

Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., Smart, P. 2003. Towards a

Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed

Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic

Review. British Journal of Management. 14. pp. 207-

222.

van Hoof, B., Lyon, T. P. 2013. Cleaner Production in

Small Firms taking part in Mexico´s Sustainable

Supplier Program. Journal of Cleaner Production. 41,

pp. 270-282.

Wetterberg, A. 2011. Public-private partnership in labor

standards governance: Better factories Cambodia.

Public Administration and Development. 31. 1. pp. 64-

73.

Wilhelm, M., Blome, C., Wieck, E., Xiao, C. Y. 2016.

Implementing sustainability in multi-tier supply

chains. Strategies and contingencies in managing sub-

suppliers. International Journal of Production

Economics. 182. pp. 196-212.

Xu, Y., Boh, W.F., Luo, C., Zheng, H. 2018. Leveraging

industry standards to improve the environmental

sustainability of a supply chain. Electronic Commerce

Research and Applications. 27. pp. 90-105.

Zhang, M., Pawar, K. S., Bhardwaj, S. 2017. Improving

supply chain social responsibility through supplier

development. Production Planning & Control. 28. 6-

8. pp. 500-511.

The Role of Third-parties in Sustainable Supply Chain Management: A Systematic Literature Review

223