Linguistic Taxonomies for Teaching English at a Technical University

Alexandra Alyabeva

a

and Ekaterina Ites

b

Novosibirsk State Technical University, Novosibirsk, Russian Federation

Keywords: Linguistic Terminology, Bilingual Taxonomies, Grammar Skills, Academic Competences.

Abstract: Underdeveloped awareness of and skill in using linguistic terminology is viewed as one of the factors that

compromises mastering the English language at a technical university. Drawing from an ecological semiotic

perspective on a language as a technology of meaning construction, the role of linguistic terminology in

foreign language learning becomes obvious. It requires innovative instructional designs that support students’

acquisition and mastering of this important group of academic vocabulary. Bilingual classifications of

linguistic terms as one of such instruments were introduced as a curricular intervention. An experiment was

conducted to evaluate the classifications’ efficiency. Its results have revealed that students who systematically

worked with the classifications possessed a higher level of knowledge of grammar terminology and

metalinguistic skills in comparison with those who did not work with the classifications.

1 INTRODUCTION

At the current stage of technological development the

demand for well-educated specialists grows. It

contrasts with the situation that most students

entering technical universities often lack the basic

skills and competences even in their native language.

Their knowledge of linguistic terminology, even that

of grammar they studied at school, is especially weak.

The task of university professors and teachers is to

create such conditions for study which could

substantially improve their knowledge and facilitate

intellectual growth. The role of foreign language (FL)

instruction is to contribute to this mission by helping

students develop various competences in academic

language, especially genre competences

(Kolesnikova, 2018), in the target language and the

first one alike. To make it happen, different methods

and approaches can be applied. One of them is

developing academic vocabulary by promoting

acquisition of terminology in the area of

specialisation, along with linguistic terms. In doing

so, it is important to teach linguistic terminology as a

system. This approach would help students

systematise the fragmentary knowledge they bring

from school, come to a deeper understanding of the

terms’ meaning, and learn how to apply them when

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7544-5811

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2102-4004

using language. The understanding that this task is a

challenge is present in the FL teaching field.

University instructors are concerned about how to

help their students to acquire grammar terminology in

the target language based on the upgrading of often

fragmentary knowledge of their native language

terminology (De Faria, 2021).

Teaching language as a technology implies the

introduction of new instructional materials and

algorithms of their use, thus expanding the range of

pedagogical technologies in the foreign language

classroom. Bilingual linguistic classifications, or

taxonomies, can be considered as such innovative

means, or know-how tools, that allow for an ongoing

practice and systemic acquisition of this group of

academic vocabulary.

Acquiring linguistic terminology in the form of

classification helps students to better understand each

term and complex semantic relationships among

them. It also prepares students for understanding the

role and workings of terminology in their future area

of specialisation, which they are to acquire both in

their first language and in English. Thanks to strong

skills in Russian and English linguistic terminology,

students develop metalinguistic and cognitive skills.

Obtaining the former supports their abilities to see the

whole/part, to generalise/analyse, deduce, and so on.

92

Alyabeva, A. and Ites, E.

Linguistic Taxonomies for Teaching English at a Technical University.

DOI: 10.5220/0011607700003577

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Actual Issues of Linguistics, Linguodidactics and Intercultural Communication (TLLIC 2022), pages 92-98

ISBN: 978-989-758-655-2

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In the FL classroom, the term ‘linguistic

terminology’ is usually understood narrowly as

grammar terminology. This treatment leaves behind

some important elements of the language system that

students need to be aware of and able to work with.

Among others, these include word building, systemic

relations in lexis, and stylistic features. Linguistic

terminology equips students with tools they need to

analyse and construct various messages and texts of

different genres. This is true not only for language

students whose future profession will be connected

with the language but also for students of all different

specialties, for example for future teachers

(Ryabukhina, 2019). Thus, the ability to interpret text

based on its form and language is a compulsory

academic skill that all university students have to

master.

The place of grammar teaching in the foreign

language classroom and especially how this has to be

done has always been controversial and requires new

innovative approaches (Pawlak, 2021). There are

different views on the question as to whether the

linguistic terminology has to be taught in the English

language classroom and how. These views are

grounded in more general theories of language,

language learning and teaching. Behind this diversity

there might be distinguished four main perspectives

on what language is. These include structural,

cognitive, interactive (communicative) and socio-

cultural (semiotic) approaches.

The structural approach dates back to the ideas of

a Swiss linguist F. de Saussure. According to his

theory, language is a semiotic system consisting of

units of different levels (De Saussure, 1959). From

this perspective teaching grammar is an inalienable

component in a foreign language classroom which

has been implemented in such methods of foreign

language instruction as grammar-translation and later

audio-lingual method (Richards, 2014; Soloncova,

2018).

The second approach to language – the cognitive

one – views language mainly as a tool of cognition

which facilitates the process of learning by making it

more conscious. It emerged in the 1950s based on

cognitive psychology studies, in particular,

psychology of education. Educational psychology

offered a general framework of school learning

objectives including the goals of students’ cognitive

development, namely their knowledge and skills.

This framework is known as Bloom’s taxonomy, or

pyramid (Bloom, 1956). Its hierarchical structure

reflects the growing complexity of cognitive

processes and learning outcomes that students have to

achieve to master the curriculum of any academic

discipline. The original taxonomy of learning

objectives had the following six levels: (1)

knowledge, (2) comprehension, (3) application, (4)

analysis, (5) synthesis, and (6) evaluation. Each level

implies certain knowledge and skills that can be

demonstrated by specific tasks. This theoretic

approach was implemented in such instructional

methods as ‘learning by doing’, functional methods,

situational and genre–based. The common feature of

these methods is that they are focused on fostering

‘good habits’. In the foreign language classroom, it

means that students are expected to acquire some

stable forms of communication in a particular cultural

context. This means grammar structures and units are

selected, introduced and taught as elements of

particular communicative situations. This reduces the

focus on teaching grammar and its terminology as a

system (Richards, 2014).

The third approach, communicative or interactive,

is linked to an American scholar in the field of

ethnography of communication, Dell Hymes. In

1966, he introduced the notion of communicative

competence as a more comprehensive term than

language skills or linguistic competence. His ideas

were inspired by a socio-cultural theory of language

and learning. According to Hymes, language learning

has to be focused on cultural practices of language use

(Hymes, 1972). It covers the four language skills

(listening, speaking, reading, and writing) and

grammar accuracy, but also highlights cultural

practices of language use, including text-based

communication forms. Despite the fact that the

communicative competence approach expanded the

scope of instructional goals in the foreign language

classroom, its practical implementation narrowed

down the number of competences pursued by teachers

who had adopted this approach. The main focus had

shifted to content and the development of students’

mostly oral performance of daily topics, which

resulted in weak lexical and grammar skills, leaving

alone the mastery of linguistic terminology. This

crisis revealed itself in numerous critical research

publications on communicative approach and

stimulated a search for new approaches to language

teaching (Bax, 2003).

A new semiotic perspective on language became

a source for new approaches to language teaching.

Based on the scholarship of L.S. Vygotsky, M.M.

Bakhtin, and the American semiotician C.S. Peirce,

socio-cultural theories of language emerged during

the 1980s. They were enriched with the notion of

design, whereas this term was adopted in

communicative linguistics and the theory of language

teaching.

Linguistic Taxonomies for Teaching English at a Technical University

93

In the US, the term ‘design’ was employed in

curricular studies in the 1980s as Bloom’s theory

(1956) was reapplied for creating school curricula and

planning instruction. The terms ‘backward design’

and ‘understanding by design (UbD)’ were

introduced (Wiggins, 1998 / 2005). The latter term

was adopted by educational linguists and researchers

of language learning. It sent the message that in

communication, it is not just content that is important

but also the context including the text itself and its

form. These researchers understood the term design

as a socially constructed process and product of

communication. This view was popularised by the

British scholar Günther Kress, credited with creating

the theory of social semiotics as a multimodal theory

of language (Kress, 2003). The theory asserts that

language use always takes place in a rich semiotic

context where other sign systems that accompany

verbal expressions might support language decoding

/ encoding or harden it. In terms of grammar teaching

the theory points out that grammar is content, genre,

and medium dependent. For example, simplified

written representation of date expressions differ

significantly from their oral form (Oct. 5 is read as

‘the fifth of October’, or ‘October the fifth’, or

‘October fifth’). So understanding grammar and

acquiring grammar terminology is important because

certain contexts of communication require full

mastery of this competence.

The theory became inspirational for a new

approach to language teaching known as multiple

literacies, or multiliteracies (Cope, 2018). It

supplemented the term ‘competence’ with the term

‘literacy’ understood broadly as the ability to use in

communication not just linguistic resources but other

semiotic means (such as music, gestures, colours,

artifacts, etc.) that help to create multimodal texts.

Introduced in 1966 by an international group of

language education scholars (the New London

Group), this approach views language not just as a

semiotic system and a design process but also as a

particular technology that has a terminology that

needs to be mastered (New London Group, 1996).

This group had attempted to generalize all the

previous approaches to teaching language and

introduced the concept ‘learning by design’ (Neville,

2008). This idea underscores that form is meaning,

and that understanding the forms of language

involves the explicit teaching of these forms and

mastering linguistic terminology is one of the tools

for achieving this goal (Kern, 2012; Cope, 2013).

From the point of view of the multimodal semiotic

approach, language is a kind of technology for

expressing and interpreting meaning via its forms,

including texts, which mediate communication and

reflect its cultural norms. Besides, the term

‘technology’ can also refer to the very approach to

teaching language and linguistic terminology. Since

in the literature devoted to the teaching of grammar

and linguistic terms, one can rarely find a detailed

description of this technology, this article attempts to

fill in this gap. It offers preliminary results of a small

experimental study. The study aimed at revealing the

level of skills in Russian linguistic terminology and

the efficiency of implementation of innovative

pedagogical materials. Introducing new pedagogical

designs is an urgent necessity in the time of fast

informatisation of society (Turlo, 2020) and

increased demands for professional training.

2 METHODS AND MATERIALS

Based on the multiliteracies semiotic approach a

curricular intervention was designed and

implemented in the form of four classifications, or

taxonomies, of linguistic terms.

The purpose of the intervention was to facilitate

the development of several academic competences.

These skills include (1) metalinguistic – the ability to

discuss language as a system and technology, (2)

metacognitive – the ability to analyse concepts, (3)

academic genres skills – understanding different texts

structures, (4) academic vocabulary – general and

field specific terminology and word formation, (5)

oral and written bilingual skills, (6) information

search, and, finally (7) language analysis and

synthesis skills.

This scope of literacies is supported by the

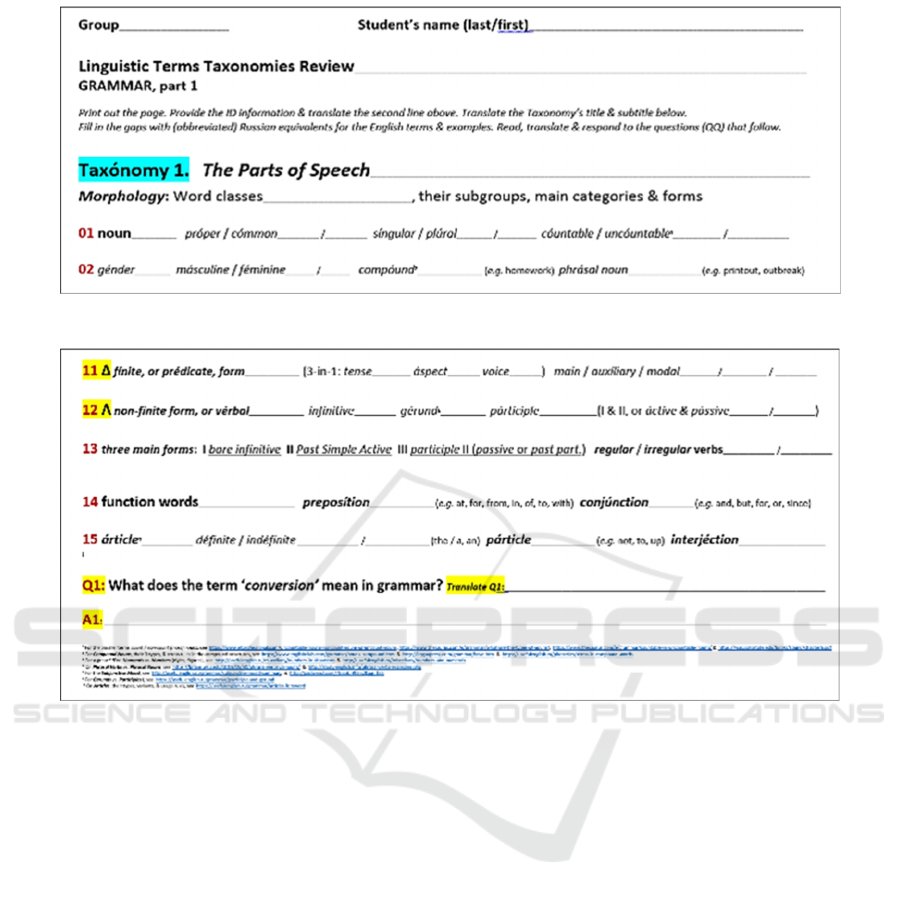

taxonomies’ one-page design. As Figure 1 shows,

each text opens up with a line to enter student’s

information. The heading, title and subtitle are

followed by terms organised in numbered lines. The

page provides instructions as to how to turn it into a

bilingual learning tool. The English terms are

followed by gaps left for Russian equivalents that

students are to fill in step by step.

The gaps’ small size allows for the Russian

equivalents to be inserted in commonly known

abbreviated forms. At the end of each taxonomy, one

to three questions are provided to be translated and

answered. Their goal is to draw students’ attention to

some important terms for the given classification, e.g.

the term ‘conversion’ in morphology. To encourage

students to explore some terms in more detail, links

to online sources are given at the very bottom of the

page, as Figure 2 shows.

This format allows the teacher to introduce, and

TLLIC 2022 - I INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE "ACTUAL ISSUES OF LINGUISTICS, LINGUODIDACTICS AND

INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION"

94

the student to practice and acquire linguistic terms as

a system and thus come to see language as a whole.

At the same time, it reveals various semantic and

formal relations between the terms, which leads to a

deeper understanding of their meanings. These

include synonymy, antonymy, homonymy, paronymy

and word building links. This way, taxonomies make

it possible for students to apply the methods of

analysis, synthesis, observation, and discovery.

Other methods were also used. The first one is the

so-called flipped classroom method. It means that

students gradually get familiar with the new material

on their own first at home (read English terms and

write down their Russian equivalents in abbreviated

form), and then their work is checked, discussed and

commented on during a frontal survey in the

classroom. When working at home, students have to

use the search method to fill in the lines of the

classification with the corresponding Russian terms

(usually they are asked to prepare 2-3 lines for the

lesson). In parallel, the norms of the abbreviated

notation of academic terminology are acquired.

The next methods are visual and systematic

methods of presenting material. It should be noted

that although the names of the parts of speech used in

both Russian and English should already be familiar

to students from school, however, introducing

grammar terminology in a systematic and visual form

is new for students and allows them to see, feel and

discuss various systemic relations between linguistic

terms and their concepts.

Students prepare 2-3 lines of translation at home,

and in class all terms and examples are read aloud and

discussed in order to correct translation errors and

practice pronunciation. This way, step by step

students create individual learning materials they use

during at least one semester of learning English. First,

they create a draft version, and after in class

discussion and error correction, students create an

error-free and edited version of taxonomy, and use it

in subsequent lessons as a reference tool as they

analyse and construct sentences and texts.

And, finally, the method of individual survey is

used to stimulate the mastery of this important group

Figure 1: Taxonomy 1, the upper part.

Figure 2: Taxonomy 1, the lower part.

Linguistic Taxonomies for Teaching English at a Technical University

95

of academic vocabulary as well as the ability to apply

it. This survey is conducted as a control task, when

students submit their final versions of classifications

for verification and evaluation.

3 EXPERIMENTS

A preliminary test was carried out to determine the

degree of formation of competence in Russian

linguistic terminology among students of the

technical university. Another goal of conducting this

experiment was to reveal if taxonomies can improve

students’ knowledge and the understanding of this

academic vocabulary. The test was designed to find

out what linguistic terms the students are aware of and

had mastered. The experiment tested the knowledge

and skills in the following areas: (1) parts of speech –

noun, adjective, numeral, adverb, pronoun, verb,

preposition, and conjunction, (2) some grammar

forms – plural number, degrees of comparison,

tense/aspect, participle/gerund, (3) students’ ability to

identify these structures and name them correctly.

The participants of the experiment were students

of a technical university. The testing involved two

groups: (1) an experiment group of students who had

worked with the classifications for one full semester,

and (2) a control group of students who had not

worked with the taxonomies. The total of 120

undergraduate students in their first or second year of

study took the test. They were split evenly between

the experiment/treatment and control groups, each

consisting of 60 participants.

Different test items required one, two or three

answers, so the maximum total number of correct

responses for different items was 60, 120, or 180

points, as shown in brackets in tables 1 and 2.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Table 1 presents data reflecting students’ knowledge

of the parts of speech and their ability to identify and

correctly name these classes of words.

The results of the experiment showed that all the

students, regardless of whether they had worked with

the classifications, were able to recognize and

identify in the context of a short poem such an

important part of speech as the verb. Perhaps this is

due to the pronounced predicative nature of the

Russian language and its rich verb morphology.

However, not everyone was able to recognize a

noun when it was used not in the nominative singular

form, but in its object case (e.g., ‘без пут’ – without

fetters), or when a noun-based adverb was interpreted

as a noun (e.g., ‘поутру’ – in the morning). A deeper

problem is that the morphological term ‘part of

speech’ is often confused with the syntactic term that

refers to the syntactic position of the word under

consideration. For example, in the phrase ‘on the

bank’ – на берегу – instead of identifying ‘bank’ as

a noun, students use the Russian term for ‘adverbial

modifier’. The same confusion is observed when the

Russian term for ‘adjective’ is replaced by the

syntactic term for ‘attribute’ or ‘modifier’, and

instead of the morphological term ‘adverb’ the

Russian term for ‘adverbial modifier’ is used.

Table 1: Parts of speech knowledge.

Parts

of speech

Croup 1

correct

answers

Group 2

correct

answers

Verb 120

(

of 120

)

120

(

of 120

)

Noun 115

(

of 120

)

110

(

of 120

)

Ad

j

ective 60

(

of 60

)

57

(

of 60

)

Adverb 51 (of 60) 48 (of 60)

Numeral 57 (of 60) 57 (of 60)

Pronoun 60

(

of 60

)

56

(

of 60

)

Con

j

unction 47

(

of 60

)

46

(

of 60

)

Pre

p

osition 101

(

of 120

)

99

(

of 120

)

The greatest confusion in both groups was

observed when students had to identify function parts

of speech. Thus, the Russian adversative conjunction

‘a’ meaning ‘but’ was referred to as preposition,

particle or even interjection. A similar confusion of

terms occurred with identifying the preposition ‘без’

meaning ‘without’.

Table 2 presents the test results that reflect

students' understanding of grammar forms of

different parts of speech.

Table 2: Grammatical forms knowledge.

Grammar form Croup 1

correct answers

Group 2

correct answers

Plural noun 25

(

of 60

)

29

(

of 60

)

Verbal 77

(

of 120

)

23

(

of 120

)

Verb aspect 38 (of 60) 20 (of 60)

Verb tense 175 (of 180) 163 (of 180)

Com

p

arison de

g

ree 131

(

of 180

)

95

(

of 180

)

As it can be seen from the table, the majority of

students had difficulty identifying the plural number

form of the noun used in the phrase ‘без пут’ (without

fetters) within a short verse. Some participants gave

no answer at all, others failed to understand the term

‘the number meaning’ in the test assignment. Instead

TLLIC 2022 - I INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE "ACTUAL ISSUES OF LINGUISTICS, LINGUODIDACTICS AND

INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION"

96

of the right answer ‘the plural meaning’ some

students suggested the opposite answer (i.e.,

singular), while others, instead of using a grammar

term for the number form, tried to figure out the

lexical meaning of the noun ‘путы’ (fetters).

One of the tasks on verb forms tested the ability

to distinguish between the two verbals or non-finite

forms (gerund and participle). The numerical results

of the task in the two groups differed significantly. In

the treatment group, the total result of the task (77 of

120, or 70.4%) was more than twice higher than that

in the control group (23 of 120, or 27.3%).

The conducted test experiment revealed that both

groups demonstrated slightly better outcomes on

tasks requiring students to identify such verb forms as

aspect and tense. It is worth noting that identifying

aspect forms turned out to be more challenging a task

compared to tense forms, which by large did not pose

a serious problem. However, in some cases of naming

the forms, the participants demonstrated inaccurate

knowledge of the conventional terminology. For

example, in the Russian term ‘прошедшее время’

(i.e. past tense), they sometimes mistakenly

substituted the adjective ‘прошедшее’ with a

paronymous word ‘прошлое’. The confusion

between these cognate adjectives might in part be

accounted for the fact that they both correspond to the

English adjective ‘past’, which does not distinguish

between the slightly different meanings of the two

Russian words.

More often problems were observed when

students were asked to identify degree of comparison

forms in adjectives. As a rule, the term ‘zero degree’

was not familiar to students who had not worked with

the classifications. As a rule, the intended grammar

term was not usually provided by the participants, or

alternatively, some expressions (semantically close to

the expected term) were offered instead. Those can be

translated as ‘ordinary, basic, simple’.

In discussing the observed outcomes regarding

students’ knowledge of terms for the parts of speech

(Table 1), it is necessary to point out that the

participants in both groups were able to identify

correctly most of the content parts of speech. They

generally performed the related tasks with fewer

mistakes than when dealing with other items on the

test. However, the knowledge of function words and

their names was much weaker in both groups.

Accordingly, in further work with classifications,

more attention should be paid to students’ acquisition

of the function words and close observations on how

these expressions are used in the two languages.

In discussing the results presented in Table 2, it

should be pointed out that a surprising failure at

identifying ‘the plural form’ was observed in both

groups. The low outcome can be explained in part by

the fact that the participants came from different

faculties, and the average level of academic skills

may differ across faculties. Another factor for the low

result could be the fact that the form ‘пут’ introduced

by the prepositional phrase ‘без пут’ (without

fetters), belongs to a low-frequency vocabulary in

Russian language of today, and that circumstance

might have caused difficulty with understanding.

The ability or inability to distinguish verb forms

differ significantly in the two groups. Students from

the control group (group 2) who did not work with the

classifications do not usually possess the targeted

knowledge and skills. This seems to provide evidence

that the acquisition of linguistic terminology through

work with bilingual classifications significantly

increases students’ metalinguistic skills, including

their native language. Attention, however, should be

paid to the very concept of ‘grammatical form’, which

is complex and caused difficulty for some students.

The complex category of the verb aspect turned

out to a problematic issue for both groups.

Nevertheless, the results demonstrated by the

treatment group (38 of 60) were 33.3 % higher than

those produced in the control group (38 of 20), which

also speaks in favour of the presented approach.

The category of grammar tense turned out to be

sufficiently mastered by all students and did not cause

difficulties for students identifying all three tense

forms. All the errors observed here were related to

naming the past tense form by using a paronymous

expression.

Knowledge of the terms for degrees of

comparison differed significantly in the two groups.

In the first group, all degrees were named, but there

were errors in naming the zero degree form. In the

second group, students either did not use the degree

terms at all, or applied them incorrectly, or provided

non-term expressions. This difference in performance

also testifies to the effectiveness of terms taxonomies

as a tool for spurring academic literacies.

5 CONCLUSIONS

As the study has revealed, students who are doing

their studies at technical universities usually lack

strong knowledge of Russian linguistic terminology.

This hardens their learning of English as an FL,

including mastering academic skills in its grammar

terminology and other linguistic terms. Therefore, the

use of bilingual classifications of linguistic terms in

the process of teaching English as a technology of

Linguistic Taxonomies for Teaching English at a Technical University

97

meaning construction and sharing could promote

students’ metalinguistic skills and language

proficiency not only in English, but also in Russian.

At the next stage of the reported intervention

study, it will be necessary to analyse the results of

students’ performance of the second section of the

reported experiment test. Designed to reveal students’

awareness of and skills in using Russian syntactic

terminology, the second part elicits and evaluates

students’ skills at applying this particular area of

academic vocabulary.

REFERENCES

Bax, S., 2003. The end of CLT: a context approach to

language teaching. ELT Journal. 57 (3).

Bloom, B. S., Krathwohl, D. R., 1956. Taxonomy of

Educational Objectives; the Classification of

Educational Goals by a Committee of College and

University Examiners. Handbook I: Cognitive Domain.

Cope, B., Kalantzis, M., 2013. “Multiliteracies”: new

literacies, new learning. Framing Languages and

Literacies: Socially Situated Views and Perspectives.

Cope, B., Kalantzis, M., Smith, A., 2018. Pedagogies and

literacies, disentangling the historical threads: an

interview with Bill Cope and Mary Kalantzis. Theory

into Practice. 57(1).

De Faria, R.T., 2021. Linguistic terminologies in the

teaching of classical languages (cl) and Portuguese

(ep): the case of syntactic functions. Matches and

mismatches. Boletim de Estudos Classicos 66.

De Saussure, F., 1959. Course in General Linguistics.

Hymes, D.H., 1972. On communicative competence.

Sociolinguistics.

Kern, R., 2012. Chapter 20, Literacy-based language

teaching. Cambridge Guide to Pedagogy and Practice

in Second Language Teaching.

Kolesnikova, N.I. Ridnaya, Y.V., 2018. Forming foreign

students' genre competence in scientific sphere of

communication. Language and Culture, 44th

International Conference.

Kress, G.R., 2003. Literacy in the New Media Age.

Moore, R., Lopes, J., 1999. Paper templates. In

TEMPLATE’06, 1st International Conference on

Template Production.

Neville, M., 2008. Teaching multimodal literacy using the

learning by design approach to pedagogy.

New London Group, 1996. A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies:

Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review.

66(1).

Pawlak, M., 2021. Teaching foreign language grammar:

New solutions, old problems. Foreign Language

Annals. 54(4).

Richards, J., Rodgers, T., 2014. Approaches and Methods

in Language Teaching.

Ryabukhina., E.A., 2019. Methodological analysis and

methodological interpretation as methods of

implementation of competency-based approach to

training future teachers of the Russian language.

ARPHA Proceedings of the Fifth International Forum

on Teacher Education (IFTE).

Smith, J., 1998. The book, 2

nd

edition.

Soloncova, L.P., 2018. Methodology of foreign language

teaching in 3 parts, Part 3 - History of foreign language

teaching.

Turlo, Y., Alyabeva, A., 2020. Technology of forming

competence of pedagogical design in graduate and

postgraduate programs. Proceedings of the Conference

on Integrating Engineering Education and Humanities

for Global Intercultural Perspectives (IEEHGIP 2020),

Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems. 131.

Wiggins, G., McTighe, J., 1998 / 2005. Understanding by

Design, 2nd edition.

TLLIC 2022 - I INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE "ACTUAL ISSUES OF LINGUISTICS, LINGUODIDACTICS AND

INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION"

98