Study on the Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation in the

Relationship of Young Adults’ Attachment Security with Parents

and Their Anxiety Symptoms Based on SPSS

Tongtong Meng

School of Health in Social Science, the University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland, EH8 9AG, U.K.

Keywords: Attachment, Emotion Reregulation, Mediation, Anxiety Symptom.

Abstract: Attachment theory provided a comprehensive framework to understand anxiety. Researchers suggested that

there is theoretical and empirical evidence for the interrelationships between attachment security, emotion

regulation (ER) and anxiety of young adults. However, the nature between the two constructs still remains

explored. The purpose of this study was to test whether the path from young adults' attachment security with

parents to the levels of anxiety symptoms was mediated by their difficulties in ER. 109 participants who were

16 to 26 years old attended the current study by completing relevant questionnaires. Based on mediation

model, the author used SPSS to analyze the dataset. According to the results, attachment security was

significantly correlated to anxiety without the inclusion of ER (r=-0176, p<0.05). When including the

difficulties in ER in the model, this direct relationship became insignificant, b=0.004, 95% CI [-0.037, 0.045],

t=0.180, p=0.857. Furthermore, the indirect effect was shown as b=-0.046, 95% CI [-0.081, -0.018].

Accordingly, these results indicated that the relationship between attachment security and anxiety was fully

mediated by ER. In conclusion, compared to individuals with insecure attachment, securely attached young

adults reported fewer difficulties to regulate their emotions, which further reduced their levels of anxiety

symptoms. These outcomes are discussed regarding meanings for both future directions and clinical practices.

1 INTRODUCTION

The shared features of anxiety disorders are

characterized by both excessive fear and anxiety and

related behavioral disturbances (American

Psychiatric Association, 2013). These anxiety

symptoms have been regarded as the central to many

psychopathological disorders due to their high

correlation with the diagnosis of internalizing and

externalizing disorders (Crocq, 2017; Cosgrove,

2011; Eaton, 2013). A study has reviewed worldwide

empirical results from 1985 to 2012 and indicated

that the average prevalence of anxiety disorders for

children and young people was 6.5% (Polanczyk,

2015). Therefore, anxiety disorders are considered to

be one of the most prevalent mental disorder during

childhood, adolescence and even through the lifespan

(Albano, 2003; Bittner, 2007; Steel, 2014). At the

same time, anxiety symptoms under the threshold of

the diagnosis of anxiety disorders were reported to

occur 3 times more (Balázs, 2013). These symptoms

are highly associated with poor physical health,

ongoing anxiety, more risks of psychopathology and

negative development of cognitive and social

functioning (Copeland, 2014; Simpson, 2010; Walker,

2015). Therefore, exploring the etiology of anxiety

symptoms merits more attention.

The attachment theory has been provided with a

comprehensive framework to understand the

underlying mechanism of the emergence and

development of anxiety symptoms. Infants used

attachment as a survival system through interaction

with their caregivers to express their needs (e.g., food

and safety) (Bowlby, 1969). When these needs are

satisfied reliably and consistently by caregivers over

time, infants would regard the caregivers as secure

bases that they can turn to when experiencing

distress. A secure attachment is therefore fostered.

However, if caregivers neglect, or respond to infants

with inconsistency and maladaptation, it is more

likely to foster an insecurely attached relationship

(Bowlby, 1982; Nolte, 2011). When having an

insecure attachment, individuals are more likely to

engage in secondary or 'second-best' strategies to deal

Meng, T.

Study on the Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation in the Relationship of Young Adultsâ

˘

A

´

Z Attachment Security with Parents and Their Anxiety Symptoms Based on SPSS.

DOI: 10.5220/0011730700003607

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Public Management, Digital Economy and Internet Technology (ICPDI 2022), pages 85-92

ISBN: 978-989-758-620-0

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

85

with their distress such as hyper activating (i.e.,

frantically attempt to draw more attention from the

attachment figure) or hypo activating strategies (i.e.,

suppression and inhibition of feelings, lack of co-

regulation) (Cassidy, 1988; Roisman, 2007).

Although these secondary strategies are adaptive to

the situation of unavailable caregivers, they are

maladaptive over time.

After repeating such dyadic attachment

experience with caregivers, individuals begin to form

representations of interpersonal experience which is

called the Internal Working Model (Bowlby, 1973).

Individuals with secure attachment tend to use

adaptive strategies to effectively regulate their

anxiety (Brumariu, 2010). On the contrary, secondary

strategies brought by insecure attachment are more

likely to cause anticipatory anxiety and

hypervigilance (Nolte, 2011). Empirical studies also

showed that insecure attachment is moderately

related to anxiety from early childhood to

adolescence (Colonnesi, 2011). In order to better

understand the nature of the relationship between

attachment and anxiety symptoms, the mediating role

of emotion regulation (ER) is examined.

ER is a dynamic and complicated series of

processes, including recognition, evaluation and

modification of both one's own and others' emotions

during interactions in various situations (Thompson,

1994). Theoretically, individuals' capacity of ER is

fostered directly and indirectly through the repeated

dyadic interaction during attachment experience with

caregivers (Fonagy, 2002). For instance, caregivers

provide children with emotional support, comfort as

well as guidance on what emotions are, how to use

and adjust them (Cassidy, 1994; Thompson, 2001).

Additionally, children would model their parents'

ways of responding to emotional arousal situations

(Denham, 2010). Empirical studies have found that

securely attached individuals would have better

understandings towards emotions, regulate their

emotions by more constructive and effective

strategies and express themselves more openly

(Crugnola, 2011; Thompson, 2007). On the contrary,

individuals with insecure attachment are more likely

to concentrate on negative emotions, lack functional

abilities to express intensive affections and regulate

the distress through an ineffective and stressful

approach (e.g., hyperactivation or hypoactivation)

(Nolte, 2011; Hershenberg, 2010; Mikulincer, 2003).

At the same time, these ER abilities are associated

with the development of anxiety symptoms. Several

studies have indicated that young adults who scored

high on difficulties in ER also reported a higher level

of anxiety than those who reported better ER

capacities (Brumariu, 2012; Bender, 2015; Esbjørn,

2012). Having better ER is also related to better social

skills such as the development of peer competence

and more engagement in adaptive social interactions

(Hyung, 2020). These skills would further help them

develop more resilience to deal with distress and

protect them from psychopathologies which are

based on emotional disturbance (e.g., anxiety

symptoms and disorders (Nolte, 2011; Brackett,

2011).

Although many empirical studies have provided

evidence for the correlations between attachment

security, ER and the development of anxiety

symptoms, most of them investigated the

relationships between the two among the three

constructs but not all three of them (Colonnesi, 2011;

Hannesdottir, 2007; Suveg, 2009). Recently, several

exceptions suggested that the relation of attachment

security and anxiety was partially mediated by ER

(Brumariu, 2012; Bender, 2015; Brumariu, 2013).

However, the majority of them focused on the sample

of children who live in western culture (Brumariu,

2012; Brumariu, 2013; Bosquet, 2006).

In order to not only increase the generalizability

of these relationships but also add more empirical

evidence of young adults (16 to 26 years old) in

Eastern culture, this study was conducted. The author

sought to investigate whether individuals' abilities of

ER indirectly mediate them to a pathway from

attachment security to correspondent levels of

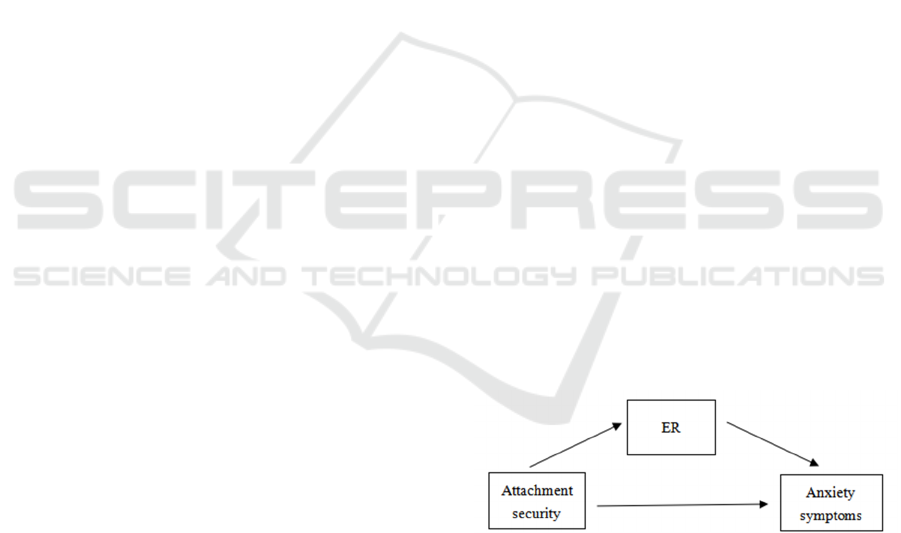

anxiety symptoms. Based on the previous theoretical

and empirical research, the hypothesis was that ER

played a mediating role between attachment and the

development of anxiety. The hypothesized mediation

model was showed in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The model of the hypothesis.

2 METHOD

2.1 Design

In the presented study, the independent variable was

young adults' attachment security with parents, which

was operationalized by the scores measured by the

Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment-Revised

(IPPA-R). The dependent variable was anxiety

ICPDI 2022 - International Conference on Public Management, Digital Economy and Internet Technology

86

symptoms, assessed by the Generalized Anxiety

Disorder 7-item Scale (GAD-7). In addition, the

difficulties in ER as a mediator was measured by the

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale-Short Form

(DERS-SF). All data were collected online. During

the statistical process, the author used SPSS to

analyze the dataset. A preliminary t-test was

conducted to examine whether there was a significant

difference of gender groups which might need to be

controlled between these variables. Then simple

correlations and mediation were conducted to

investigate the hypothesis.

2.2 Participants

Totally 109 participants attended the present study,

which consists of 87 females and 22 males. The age

of the participants ranges from 16 to 26

(mean=22.796, SD=1.830). All of them were Chinese

international students with good English level. They

were recruited on the internet through snowball. In

addition, 66.1% of them are currently postgraduate

students, 32.1% are undergraduate students and 1.8%

are high school students. 71.6% of them are currently

resident in China and others live in other countries.

The additional demographic information about the

participants is listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Demographic information of participants (n=109).

%

Gender

Female 79.8

Male 20.2

Currently resident in

China 71.6

Rest of Asian 0.9

United Kingdom 16.5

Rest of Europe 0.9

Australia/New Zealand 7.3

North/South America 2.8

Africa 0

Student type

High school student 1.8

Undergraduate 32.1

Postgraduate 66.1

2.3 Procedure

The questionnaire was amalgamated on wjx.cn. The

link of it was subsequently posted on social media

(mainly on Wechat). Participants clicked on the link

and then read through a brief introduction of the study

and the consent form. After agreeing to take part in

the study, they followed the instructions to finish a

fixed serial of scales including some simple

demographic questions, the Inventory of Parent and

Peer Attachment-Revised (IPPA-R), the Difficulties

in Emotion Regulation Scale-Short Form (DERS-SF)

and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale

(GAD-7). It took participants approximately 10 to 15

minutes to complete the scales. All participants were

voluntarily engaged in the study. Those who were no

longer willing to engage could quit the website at any

time during their participation. Participants who have

finished the test and successfully upload their data

had a chance to get a small reward.

2.4 Measure

2.4.1 Inventory of Parent and Peer

Attachment-Revised (IPPA-R)

As a self-reported scale, IPPA-R (Gullone, 2005)

aims to measure how children, adolescents or young

people perceive their attachment relationships with

parents and peers. The instrument contains 28 items

on the parent scale and 25 items on the peer scale.

Only the parent scale items were used because the

study aims to focus on attachment with parents.

Participants were required to rate to which extent the

item is consistent with their situation. A five-point

Likert scale is used, where 1 represents 'almost never

or never true' and 5 represents 'almost always or

always true'. According to the scoring instruction

(Armsden, 1989), the scale yielded a total score and 3

scores for subscales which consists of Trust (e.g., 'I

trust my parents'), Communication (e.g., 'My parents

help me to understand myself better.'), and Alienation

(e.g., 'My parents expect too much from me.'). Also,

the IPPA-R has shown good reliabilities (Cronbach’s

alpha ranging from 0.72 to 0.91) and convergent

validity (Gullone, 2005; Armsden, 1989).

2.4.2 Difficulties in Emotion Regulation

Scale-Short Form (DERS-SF)

The DERS-SF (Kaufman, 2016) is a shortened

version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation

Scale (DERS) (Gratz, 2004) which is widely used to

examine possible emotion regulation deficits. This

self-reported instrument consists of 18 items. The

respondents were required to rate how frequently the

items are consistent with their situations. This is a

five-point Likert scale with response ranging from 1

Study on the Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation in the Relationship of Young Adultsâ

˘

A

´

Z Attachment Security with Parents and Their

Anxiety Symptoms Based on SPSS

87

Table 2: Descriptive statistical results for the main variables.

M SD Minimum Maximum

Attachment with parents 103.81 17.685 55 139

ER 43.07 10.079 23 67

Anxiety level 7.07 4.244 0 19

to 5 (1 represents almost never, 5 represents almost

always). A total score was yielded as well as scores

for 6 subscales (i.e., Strategies, Non-acceptance,

Impulse, Goals, Awareness and Clarity). The DERS-

SF has been shown sound psychometric properties

across both adolescents and adult samples when

comparing with the original version (Cronbach’s

alpha for total scale is 0.7 and for all subscales are

between 0.78 and 0.91) (Kaufman, 2016).

2.4.3 The Generalized Anxiety Disorder

7-Item Scale (GAD-7)

The GAD-7 (Spitzer, 2006) is a 7-item self-reported

instrument. It aims to assess potential clinical cases as

well as the severity levels of the anxiety symptoms.

The participants need to rate how frequently they

have experienced the symptoms described by the

items over the last 2 weeks. The scale uses 0 to

represent 'not at all', 1 represents 'several days', 2

represents 'more than half the days' and 3 represents

'nearly every day'. A total score should be yielded by

summing the scores of 7 items, which ranges from 0

to 21. Additionally, scores of 5, 10 and 15 represent

mild, moderate and severe anxiety respectively. The

GAD-7 has shown high reliabilities (e.g., high test-

retest reliability) (Spitzer, 2006) and good convergent

validity (Kroenke, 2007).

3 RESULT

3.1 Preliminary Analyses

All collected data were imported and analyzed by

IBM SPSS Statistics Version 24. The descriptive

results including means, standard deviations, the

minimum and maximum of the scores of attachments

with parents, ER as well as anxiety symptoms are

listed in Table 2.

The preliminary analyses investigated whether

there was any difference in the three main variables

of males and females. These were conducted to

examine whether gender should be controlled during

the main statistical tests. Presented in Table 3, the

results showed that gender had no influence on

attachment, ER and the level of anxiety symptoms,

which means that this variable did not need to be

controlled.

Table 3: The group differences of males and females in the

main variables.

t df Sig

Attachment with parents 0.717 107 0.475

ER -0.937 107 0.351

Anxiety level -0.708 107 0.481

3.2 Correlation

The results of correlation analyses were presented in

Table 4. The scores of attachments showed a

significant negative correlation with participants

scores of ERs (r=-0.345, p<0.01). This indicated that

individuals who had a more secure attachment with

their parents tend to have fewer difficulties with ER

than those with insecure attachment. Moreover, the

difficulties in ER were positively related to the levels

of anxiety (r=0.55, p<0.01), indicating that

individuals who had more difficulties in ER were

more likely to have more anxiety symptoms than

those with better ER abilities. Also, there was a

significant correlation between attachment security

and anxiety level. Given that the coefficient was

negative, more securely attached individuals would

have lower level of anxiety symptoms (r=-0.176,

p<0.05). However, individuals with insecure

attachment tended to report more anxiety symptoms.

Table 4: The results of correlation between attachment

security, ER and anxiety symptoms.

Attachment

with

p

arents

ER

Anxiety

level

Attachment with

parents

-

−0.345

∗∗

−0.176

∗

ER - -

0.55

∗∗

Anxiety level - - -

*p<0.05, **p<0.01

3.3 Mediation

In order to investigate the mediating role of ER in the

relationship between attachment and anxiety, the

ICPDI 2022 - International Conference on Public Management, Digital Economy and Internet Technology

88

PROCESS tool in SPSS was used. In accordance with

Hayes (Hayes, 2009), 5000 resamples were

generated. The main results of the mediation are

presented in Figure 2. The attachment security with

parents was a significant predictor of young adults'

ER difficulties, b=-0.196, 95% CI [-0.299, -0.094],

t=-3.796, p<0.01. It explained 11.9% variance in the

difficulties in ER. Given that the coefficient was

negative, more security during the attachment

relationship indicated fewer difficulties in ER and

vice versa. In the meanwhile, the difficulties in ER

significantly predicted the levels of anxiety

symptoms, b=0.234, 95% CI [0.162, 0.306], t=6.426,

p<0.01. That is to say, individuals who reported more

difficulties in ER tend to report higher levels of

anxiety symptoms. After including ER as the

mediator in the relationship model, the attachment

was not a significant predictor of anxiety level,

b=0.004, 95% CI [-0.037, 0.045], t=0.180, p=0.857.

At this time, 30.3% variance in anxiety symptoms

was explained by attachment security, which was

larger than the model without ER as a mediator

(3.1%). To sum up, there was a significant indirect

effect of attachment security with parents on anxiety

symptoms through the difficulties in ER, b=-0.046,

95% CI [-0.081, -0.018].

Direct effect b=0.004, p=0.857; Indirect effect b=-0.046, 95% CI

[-0.081, -0.018]

Figure 2: The result of mediation model.

4 DISCUSSION

The current study aimed to use the mediation model

to investigate the mediating role of Chinese young

adults' ER in the indirect pathway from attachment

security with parents to the development of anxiety

symptoms. Consistent with previous studies, the

results showed that attachment security was

negatively and directly related to anxiety; Further,

this direct relationship turned to an indirect one when

including ER as a mediator. At the same time, these

results revealed how ER abilities would be significant

for young adults' anxiety development and

intervention, which could trace back to attachment

relationships.

Previous studies have hypothesized that the

difficulties in ER of individuals theoretically root in

the attachment experience with parents (Cassidy,

1988; Fonagy, 2002; Thompson, 2001; Denham,

2010). Many empirical studies also proved that

attachment security linked to ER abilities (Nolte,

2011; Crugnola, 2011; Thompson, 2007). Consistent

with the evidence, the current model indicated that

young adults with secure attachment reported

themselves to be less difficult to regulate their

emotions than those who were insecurely attached.

Additionally, individuals who scored high on

difficulties in ER also reported high levels of anxiety

symptoms. This was in line with many other cross-

sectional studies (Brumariu, 2012; Bender, 2015) that

found such relation. Apart from these direct effects,

results revealed that attachment security was

indirectly related to anxiety and ER difficulties acted

as a mediator within the indirect effect. Also, similar

relationships were reported by some longitudinal

studies, suggesting that children with insecure

attachment had more difficulties in ER, which in turn

led to more anxiety symptoms later in life (Brumariu,

2013; Bosquet, 2006).

However, some limitations need merit attention.

Firstly, similar to many previous studies (Brumariu,

2012; Bender, 2015; Brumariu, 2013), this study

relied on a self-reported scale to measure individuals'

ER difficulties. Only A few studies employed other

measurements rather than self-reported scales (i.e.,

physiological measures) (Bosquet, 2006;

Hannesdottir, 2010; Sroufe, 2005). Researchers have

argued that individual differences may influence the

construct of ER to be complex, and such differences

would be incapable for self-reported measurements to

detect (Brumariu, 2013; Amstadter, 2008; Cole,

2004). Therefore, using multiple instruments to

assess ER may be necessary and crucial for future

studies to make the results more reliable, such as

employing both physiological measures and self-

reported ones (Esbjørn, 2012; Cole, 2004). Second,

this study relied on cross-sectional data but not

longitudinal data, which means that the interpretation

of causal pathways between these variables should be

cautious (Brumariu, 2012; Bender, 2015). Second,

this study relied on cross-sectional data but not

longitudinal data, which means that the interpretation

of causal pathways between these variables should be

cautious (Brumariu, 2012; Bender, 2015). Cross-

sectional outcomes were not chronological, so it is

unable to make sure the serial sequence or bi-

direction of different variables (e.g., ER difficulties

and the emergence of anxiety symptoms) (Brumariu,

2012). Moreover, changes occurred in ER and anxiety

Study on the Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation in the Relationship of Young Adultsâ

˘

A

´

Z Attachment Security with Parents and Their

Anxiety Symptoms Based on SPSS

89

followed by age (Bender, 2015), which were difficult

to capture using cross-sectional data. Future studies

can concentrate more on longitudinal studies to

monitor possible changes in individuals' quality of

attachment and ER abilities during various life stages,

which would further explain the emergence and

development of anxiety changing with age (Bender,

2015; Esbjørn, 2012; Cole, 2004).

In the meanwhile, some other questions remained

to be studied. The present study only divided the

attachment as secure/insecure dimensions. Several

studies focused on specific classifications of insecure

attachment in the interrelations, finding the pathway

from different insecure attachment to anxiety were

different. Brumariu and his colleagues (Brumariu,

2012) suggested that disorganized attachment was

associated with some ER processes including a lack

of active coping and increased catastrophizing

interpretations. However, there was no significant

correlation between ambivalent/avoidant attachment,

ER and anxiety symptoms (Brumariu, 2012;

Brumariu, 2013). Thus, the relationships of specific

insecure attachment types, ER processes and anxiety

deserve further study and more empirical replications.

Additionally, while different gender groups showed

no significant statistical differences in ER difficulties,

this might be due to the small size of male participants

(n=22) included in the study. That is to say, the study

might lack enough statistical power to detect the

gender differences between groups. The study

conducted by Bender et al. (Bender, 2015) stated that

compared to boys, girls reported more difficulties in

ER and anxiety symptoms. However, when including

gender within the structural equation model of the

interrelationships between attachment security, ER

and anxiety, gender did not have any impact. It is

notable that another study investigated the sub-

sample of the former research and found gender

played a role in the relationship between specific

processes of ER and anxiety levels (Bender, 2012).

These give rise to the importance of further

investigation into gender differences and specific

subconstructs within the interrelationships between

the three variables.

5 CONCLUSION

In summary, this study is a promising start for

studying the relationship between young adults'

attachment security with parents and anxiety levels

that mediated by difficulties in ER. It extended the

literature by testing an intact mediation model by

including all three variables rather than just two. The

results showed that young adults who were securely

attached to their parents tended to have fewer anxiety

symptoms. And one possible explanation for this was

they were better at regulating their emotions. On the

contrary, insecurely attached individuals tended to

report more anxiety due to more difficulties in ER. In

addition, the sample in the present study was different

from the majority of previous studies, which

increased the generalizability of the relationships. At

the same time, these findings are meaningful for

clinical practices of young adults' anxiety symptoms.

Effective attachment- and emotion-focused

interventions may accordingly become important

components of anxiety interventions to help young

adults with different types of problems, such as

emotion-focused cognitive behavioural therapy

(ECBT) (Suveg, 2018), attachment-based family

therapy (ABFT) (Siqueland, 2005) and emotion-

focused couple therapy (Read, 2018). The author

believes that future explorations of attachment

security, ER and anxiety in more details would

benefit our understandings of the development of

anxiety symptoms and clinical practices.

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and

statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition, 2013.

doi: l0.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

A. M. Albano, B. F. Chorpita, D. H. Barlow. Anxiety

disorders. E. J. Mash, R. A. Barkley: Child

psychopathology, 2nd edition, 2003, 270–329.

A. Bittner, H. L. Egger, A. Erkanli, E. J. Costello, D. L.

Foley, A. Angold. What do childhood anxiety disorders

predict? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry,

2007, 48(12), 1174–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.

2007. 01812.x

A. F. Hayes. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical

mediation in the new millennium. Communication

Monographs, 2009, 76, 408–420.

A. Amstadter. Emotion regulation and anxiety disorders.

Anxiety Disorders, 2008, 22, 211–221. doi:

10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.02.004

B. H. Esbjørn, P. K. Bender, M. L. Reinholdt-Dunne, L. A.

Munck, T. H. Ollendick. The Development of Anxiety

Disorders: Considering the Contributions of

Attachment and Emotion Regulation. Clinical child and

family psychology review, 2012, 15(2), 129-143. doi:

10.1007/s10567-011-0105-4

C. Colonnesi, E. M. Draijer, G. J. J. M. Stams, C. Van der

Bruggen, S. Bo ̈gels, M. J. Noom. The relation between

insecure attachment and child anxiety: A meta-analytic

review. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent

Psychology, 2011, 40(4), 630–645. doi:

10.1080/15374416.2011.581623

ICPDI 2022 - International Conference on Public Management, Digital Economy and Internet Technology

90

C. R. Crugnola, R. Tambelli, M. Spinelli, S. Gazzotti, C.

Caprin, A. Albizzati. Attachment patterns and emotion

regulation strategies in the second year. Infant behavior

& development, 2011, 34(1), 136-151. doi:

10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.11.002

C. Suveg, E. Sood, J. S. Comer, P. C. Kendall. Changes in

emotion regulation following cognitive-behavioral

therapy for anxious youth. Journal of Clinical Child and

Adolescent Psychology, 2009, 38(3), 390–401. doi:

10.1080/15374410902851721

C. Suveg, A. Jones, M. Davis, M. L. Jacob, D. Morelen, K.

Thomassin, M. Whitehead. Emotion-Focused

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Youth with Anxiety

Disorders: A Randomized Trial. Journal of abnormal

child psychology, 2018, 46(3), 569-580. doi:

10.1007/s10802-017-0319-0

D. K. Hannesdottir, & T. H. Ollendick. The role of emotion

regulation in the treatment of child anxiety disorders.

Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 2007,

10(3), 275–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-007-

0024-6

D. K. Hannesdottir, J. Doxie, M. A. Bell, T. H. Ollendick,

C. D. Wolfe. A longitudinal study of emotion regulation

and anxiety in middle childhood: Associations with

frontal EEG asymmetry in early childhood.

Developmental Psychobiology, 2010, 52(2), 197–204.

doi: 10.1002/dev.20425

D. L. Read, G. I. Clark, A. J. Rock, W. L. Coventry, J. M.

Trombello. Adult attachment and social anxiety: The

mediating role of emotion regulation strategies. PloS

one, 2018, 13(12), p.e0207514-e0207514. doi:

10.1371/journal.pone.0207514

E. R. Walker, R. E. McGee, B. G. Druss. Mortality in

mental disorders and global disease burden

implications: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

JAMA Psychiatry, 2015, 72, 334–341.

E. Gullone, K. Robinson. The Inventory of Parent and Peer

Attachment-Revised (IPPA-R) for children: a

psychometric investigation. Clinical psychology and

psychotherapy, 2005, 12(1), 67–79. doi:

10.1002/cpp.433

E. A. Kaufman, M. Xia, G. Fosco, M. Yaptangco, C. R.

Skidmore, S. E. Crowell. The Difficulties in Emotion

Regulation Scale Short Form (DERS-SF): Validation

and Replication in Adolescent and Adult Samples.

Journal of psychopathology and behavioral assessment,

2016, 38(3), 443-455. doi: 10.1007/s10862-015-9529-3

G. V. Polanczyk, G. A. Salum, L. S. Sugaya, A. Cay, L. A.

Rohde. Annual research review: A meta-analysis of the

worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children

and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and

Psychiatry, 2015, 56(3), 345–365. doi:

10.1111/jcpp.12381

G. I. Roisman. The psychophysiology of adult attachment

relationships: autonomic reactivity in marital and

premarital interactions. Developmental psychology,

2007, 43, 39–53. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.1.39

G. Armsden, M. T. Greenberg. University of Washington:

The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA),

Unpublished manuscript, 1989.

H. B. Simpson, Y. Neria, R. Lewis-Fernandez, F. Schneier.

Cambridge University Press: Anxiety disorders, theory,

research, and clinical perspectives, 2010.

J. Balázs, M. Miklósi, Á. Keresztény, C. W. Hoven, V.

Carli, C. Wasserman, D. Cosman. Adolescent

subthreshold-depression and anxiety: Psychopathology,

functional impairment and increased suicide risk.

Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 2013, 54,

670–677.

J. Bowlby. Attachment. Basic Books: Attachment and Loss

(Vol. 1), 1969.

J. Bowlby. Attachment. Basic Books: Attachment and Loss

(2nd ed., Vol. 2), 1982.

J. Cassidy, R. R. Kobak. Avoidance and its relationship

with other defensive processes. J. Belsky, T.

Nezworski: Clinical Implications of Attachment, 1988,

pp. 300–323.

J. Bowlby. Separation, anxiety and danger. Basic Books:

Attachment and Loss (Vol. 2), 1973.

J. Cassidy. Emotion regulation: Influences on attachment

relationships. Monographs of the Society for Research

in Child Development, 1994, 59(2/3), 228-249. doi:

10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994. tb01287.x

K. L. Gratz, L. Roemer. Multidimensional Assessment of

Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development,

Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of

psychopathology and behavioral assessment, 2004, 26,

41-54. doi: 10.1023/B: JOBA.0000007455.08539.94

K. Kroenke, R. L. Spitzer, J. B. W. Williams, P. O.

Monahan, B. Löwe. Anxiety Disorders in Primary Care:

Prevalence, Impairment, Comorbidity, and Detection.

Annals of internal medicine, 2007, 146(5), 317-325.

doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004

L. E. Brumariu, K. A. Kerns. Parent–child attachment and

internalizing symptoms in childhood and adolescence:

A review of empirical findings and future directions.

Development and psychopathology, 2010, 22(1), 177-

203. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990344

L. E. Brumariu, K. A. Kerns, A. Seibert. Mother–child

attachment, emotion regulation, and anxiety symptoms

in middle childhood. Personal relationships, 2012,

19(3), 569-585. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811. 2011.

01379.x

L. E. Brumariu, I. Obsuth, K. Lyons-Ruth. Quality of

attachment relationships and peer relationship

dysfunction among late adolescents with and without

anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 2013,

27(1), 116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.09.002

L. A. Sroufe. Attachment and development: A prospective,

longitudinal study from birth to adulthood. Attachment

& Human Development, 2005, 7(4), 349–367. doi:

10.1080/14616730500365928

L. Siqueland, M. Rynn, G. S. Diamond. Cognitive

behavioral and attachment based family therapy for

anxious adolescents: Phase I and II studies. Journal of

anxiety disorders, 2005, 19(4), 361-381. doi:

10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.04.006

Study on the Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation in the Relationship of Young Adultsâ

˘

A

´

Z Attachment Security with Parents and Their

Anxiety Symptoms Based on SPSS

91

M. A. Crocq. (2017). The history of generalized anxiety

disorder as a diagnostic category. Dialogues in Clinical

Neuroscience, 2017, 19, 107–116.

M. Mikulincer, P. R. Shaver, D. Pereg, D. Attachment

theory and affect regulation: The dynamics,

development and cognitive consequences of

attachment-related strategies. Motivation and Emotion,

2003, 27(2), 77–102. doi:10.1023/A:1024515519160

M. A. Brackett, S. E. Rivers, P. Salovey. Emotional

intelligence: implications for personal, social,

academic, and workplace success. Social and

Personality Psychology Compass, 2011, 5(1), 88-103.

doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00334.x

M. Bosquet, B. Egeland. The development and

maintenance of anxiety symptoms from infancy through

adolescence in a longitudinal sample. Development and

Psychopathology, 2006, 18(2), 517–550. doi:

10.1017/S0954579406060275

N. R. Eaton, R. F. Krueger, K. E. Markon, K. M. Keyes, A.

E. Skodol, M. Wall, D. S. Hasin, B. F. Grant, S.

Goodman. The structure and predictive validity of the

internalizing disorders. Journal of Abnormal

Psychology, 2013, 122, 86–92. doi: 10.1037/a0029598

P. Fonagy, M. Target. Early intervention and the

development of self-regulation. Psychoanalytic Inquiry,

2002, 22(3), 307–335. doi:

10.1080/07351692209348990

P. K. Bender, M. Sømhovd, F. Pons, M. L. Reinholdt-

Dunne, B. H. Esbjørn. The impact of attachment

security and emotion dysregulation on anxiety in

children and adolescents. Emotional and behavioural

difficulties, 2015, 20(2), 189-204. doi:

10.1080/13632752.2014.933510

P. M. Cole, S. E. Martin, T. A. Dennis. Emotion regulation

as a scientific construct: Methodological challenges and

directions for child development research. Child

Development, 2004, 75(2), 317–333. doi:

10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00673.x

P. K. Bender, M. L. Reinholdt-Dunne, B. H. Esbjørn, F.

Pons. Emotion Dysregulation and Anxiety in Children

and Adolescents: Gender Differences. Personality and

Individual Differences, 2012, 53(3), 284–288. doi:

10.1016/j.paid.2012.03.027

R. A. Thompson. Emotion Regulation: A Theme in Search

of Definition. Monographs of the Society for Research

in Child Development, 1994, 59(2–3), 25–52. doi:

10.2307/1166137

R. A. Thompson. Childhood Anxiety Disorders from the

Perspective of Emotion Regulation and Attachment. M.

W. Vaseym, M. R. Dadds (Eds.): The developmental

psychopathology of anxiety, 2001.

R. A. Thompson, S. Meyer. Socialization of emotion

regulation in the family. J. J. Gross (Ed.): Handbook of

emotion regulation (pp. 249–268), 2007.

R. Hershenberg, J. Davila, A. Yoneda, L. R. Starr, M. R.

Miller, C. B. Stroud, B. A. Feinstein. What I like about

you: The association between adolescent attachment

security and emotional behavior in a relationship

promoting context. Journal of adolescence (London,

England.), 2010, 34 (5), 1017-1024. doi:

10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.11.006

R. L. Spitzer, K. Kroenke, J. B., W. Williams, B. Löwe. A

Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety

Disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of internal medicine

(1960), 2006, 166(10), 1092-1097. doi:

10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

S. A. Denham, H. H. Bassett, T. M. Wyatt. Gender

differences in the socialization of preschoolers'

emotional competence. New directions for child and

adolescent development, 2010, 128, 29-49. doi:

10.1002/cd.267

T. Nolte, J. Guiney, P. Fonagy, L. C. Maye, P. Luyten.

Interpersonal stress regulation and the development of

anxiety disorders: An attachment-based developmental

framework. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 2011,

5, 55. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2011.00055

V. E. Cosgrove, S. H. Rhee, H. L. Gelhorn, D. Boeldt, R.

C. Corley, M. A. Ehringer, S. E. Young, J. K. Hewitt.

Structure and etiology of co-occurring internalizing and

externalizing disorders in adolescents. Journal of

Abnormal Child Psychology, 2011, 39, 109–123. doi:

10.1007/s10802-010-9444-8

W. E. Copeland, A. Angold, L. Shanahan, E. J. Costello.

Longitudinal patterns of anxiety from childhood to

adulthood: The Great Smoky Mountains Study. Journal

of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent

Psychiatry, 2014, 53, 21–33. doi:

10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.017

Y. O. Hyung. A Structural Relationship among Parental

Attachment, Emotional Intelligence, Social Skill and

Peer Relations of Early Adolescents. The Korean

Society for Child Education, 2020, 29(2), 67-90. doi:

10.17643/KJCE.2020.29.2.04

Z. Steel, C. Marnane, C. Iranpour, T. Chey, J. W. Jackson,

V. Patel, D. Silove. The global prevalence of common

mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-

analysis 1980-2013. International Journal of

Epidemiology,2014, 43, 476–493. doi:

10.1093/ije/dyu038

ICPDI 2022 - International Conference on Public Management, Digital Economy and Internet Technology

92