Community Resilience Analysis on Displaced Residents now Living in

Rusunawa Marunda

Sherley Runtunuwu

a

, Febriane Paulina Makalew

b

, Deyke Junita Femeli Mandang

and Estrellita Varina Yanti Waney

Manado State Polytechnic, Department of Civil Engineering, Polytechnic Campus Street, Manado, Indonesia

mandangdeyke22@gmail.com, ewaney@gmail.com

Keywords: Community Resilience, Urbanization, Relocation.

Abstract: Increasing urbanization rates have made Jakarta the second biggest urbanized area in the world. Some impacts

of the high urbanization rate are the emergence of slums, social and economic gaps, unemployment, crime,

and pollution. The government of Jakarta has tried to straighten up the areas belonging to the government that

the community converts into homes and economic centers. The people were relocated to Rusunawa provided

by the government, one of which is Rusunawa Marunda in North Jakarta. However, after the relocation and

displacement, other problems emerged because the people lost their job and needed to adapt to their new

environment. This study aimed to examine the community resilience of displaced residents living in

Rusunawa Marunda. Community resilience represents the ability of the community to lessen, adapt, and

recover from an unfortunate event or shock. Data were collected using questionnaires, interviews, and

observations. Data were analyzed using Structural Equation Modelling based on Partial Least Square. Our

findings confirmed that the community resilience of the displaced residents living in Rusunawa Marunda was

formed by the ecological, social, cultural, and physical aspects. However, the economy, human resources,

politics, and technology did not create the community resilience of displaced residents living in Rusunawa

Marunda.

1 INTRODUCTION

As the capital city of Indonesia, Jakarta has become

the center of economic and political activities; this

has made Jakarta the second largest urbanized area in

the world after Tokyo-Yokohama (Demographia,

2019). The urbanization rate of an urban area like

Jakarta has brought positive changes, including

improvement in public transportation, infrastructure

development (roads, bridges, and others), economic

activities, public welfare, facilities, public services,

and quality human resources.

However, there are also some setbacks from the

urbanization rate. Vulnerability in megacities starts

from an unplanned urbanization process, resulting in

a loss of governability (Kraas and Mertins, 2014). In

addition, unplanned urbanization leads to negative

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2274-0566

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3625-3996

impacts, including the emergence of slums, social and

economic inequality, unemployment, crime,

conversion of public land, water and air pollution, and

increased risk of natural disasters (Pravitasari, 2018).

Since 2013, the government of Jakarta has tried to

straighten up the areas belonging to the government

that the community has converted into homes and

economic centers illegally. The government has

moved these people to rumah susun sederhana sewa

(Rusunawa)

3

. The reasons for relocation include city

planning, the government’s limited capacity to

provide funding for decent housing, and

modernization (Wilhem, 2011).

The people living on the government’s land

illegally are often reluctant to be relocated because

they say they have lived in the area for so long. Other

reasons for refusing the relocation include not having

3

Simple apartments—they usually come in multi-storey

buildings built by the government in a residential area and

rented out to underprivileged families with monthly

payments.

Runtunuwu, S., Makalew, F., Mandang, D. and Waney, E.

Community Resilience Analysis on Displaced Residents now Living in Rusunawa Marunda.

DOI: 10.5220/0011819900003575

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Applied Science and Technology on Engineer ing Science (iCAST-ES 2022), pages 547-552

ISBN: 978-989-758-619-4; ISSN: 2975-8246

Copyright © 2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

547

the money needed to rent decent houses or Rusunawa

and being afraid of losing their current jobs or

livelihood. They also say that getting home

ownership credit is complicated. The following

reason is their need for a rather big house because

they have a big family of more than four people. They

also need additional rooms in their home to do their

job as carpenters, farmers, or traders or to live near

their business sites. The other reasons include

inadequate public and social infrastructure and

facilities in Rusunawa, the weak position as tenants

of Rusunawa, especially dealing with Sales and

Purchase Agreements (SPA) of Rusunawa units, and

many other reasons (megapolitan.kompas.com,

2015).

Nevertheless, the government of Jakarta

continues the relocation process despite the

unwillingness of those people living on the

government’s land illegally and turning the land into

slums. The government relocates the people into

some Rusunawa buildings, including Rusunawa

Marunda in North Jakarta.

Community resilience is crucial. The government

must carefully plan how these displaced residents

adapt to the new environment, recover from the

displacement, and move on with their lives to face

challenges (sustainability) (Zautra et al., 2009). This

study aimed to examine the community resilience of

displaced residents living in Rusunawa Marunda

from many perspectives, including the economic,

social, cultural, human resource, ecological, physical,

political, and technological

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Community refers to people who live within

particular geographic boundaries, are involved in

social interactions, have one or more psychological

ties, and are bound by a place to live (Christenson et

al., 1989). Resilience is a learning process to live in

changes and uncertainties, maintain diversity for

reorganization and renewal, combine various

knowledge, and create opportunities for self-

organization (Berkes et al., 2003). Resilience theory

is a multifacet study that is being developed

continuously from many fields of study. In essence,

resilience theory discusses the strength people and

systems show to tackle difficulties.

The United State Agency for International

Development (USAID, 2013) defines resilience as the

ability of people, households, communities,

countries, and systems to lessen, adapt, and recover

from an unfortunate event or shock. Community

resilience presents as a unified interrelated capacity to

absorb, anticipate, and adapt to various types of

shocks and stresses (Aditya et al., 2015). The capacity

aims to reduce vulnerability or a condition

determined by physical, social, economic, and

environmental factors or processes (Longstaff, 2010;

Ajita and Howard, 2016; Barrow Cadbury Trust,

2012) that can put a community in danger. In

addition, community resilience can also be formed

through technological aspects. Mankiew (2006)

explains that technology is an essential factor that can

function to multiply or accumulate production output

from the capital and human resources so that the

economy experiences doubled growth. The United

Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia

and the Pacific (UNESCAP, 2016) states that

technology Information Communication (ICT) has an

important role and is an integrated part of almost

every aspect of life. Several studies confirm that

community resilience can be formed through access

to political authorities for people to voice their

aspirations (Longstaff, 2010; Atreya and Kunreuther,

2016) and to identify the potential in their community

with the knowledge and skills they have (Barrow

Cadbury Trust, 2012).

Runtunuwu (2018) identifies eight (8) aspects to

understanding community resilience for Rusunawa

residents: ecological, social, cultural, physical,

economic, human resource, political, and

3 RESEARCH METHOD

The present quantitative study emphasized

quantification in data collection and analysis with a

deductive approach. However, the quantitative design

might not be able to capture the structural and

cognitive aspects of Rusunawa residents deeply; this

could be anticipated by providing open-ended

questions in a questionnaire so that residents could

freely express their thoughts as information. Thus, the

qualitative approach was employed to gather more

comprehensive data from respondents.

3.1 Data

The population of the present study was residents of

Rusunawa Marunda. Therefore, the selection

criterion for respondents was the household head or

the housewife living in the Rusunawa unit that was

part of the relocation program by the government of

Jakarta. Data were collected through interviews and

observations.

iCAST-ES 2022 - International Conference on Applied Science and Technology on Engineering Science

548

3.2 Data Analysis

We used Structural Equation Modelling; SEM

enabled us to observe the overall relationship between

indicators and variables and the relationship between

variables.

SEM is a multivariate analysis technique that

combines aspects of factor analysis and multiple

regression analysis to allow researchers to examine a

series of dependent relationships between measured

variables and latent constructs (Hair et al., 2016).

Latent constructs cannot be measured directly but can

be determined through one or more indicators, called

measured variables, observed variables, or manifest

variables (Hair et al., 2016).

We used SEM to prove the hypothesis in this

study based on component or variance, commonly

known as Partial Least Square (PLS). The SEM-PLS

method is based on a causal relationship, where

changes in one variable affect other variables.

4 RESULT AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Outer Model Evaluation

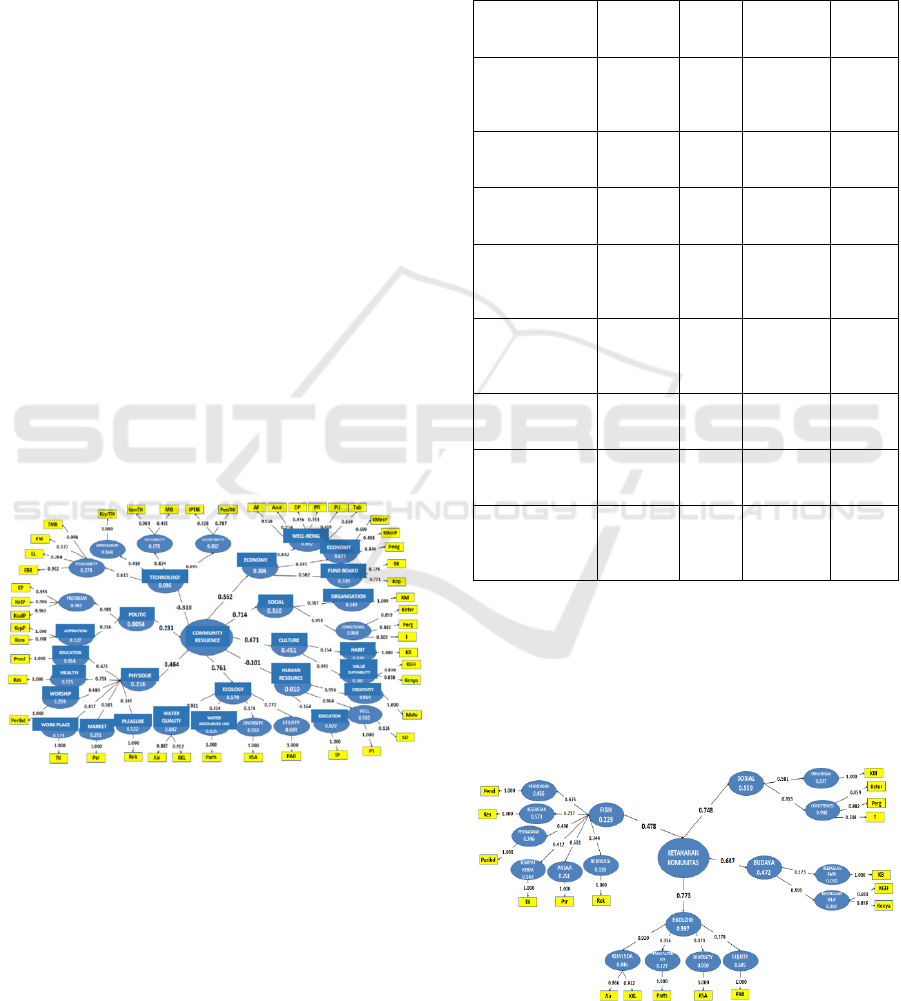

The analysis of the measurement model (outer model)

was done at a 5% significance level. The results are

shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The Initial Path Coefficients of Community

Resilience.

4.2 Inner Model Evaluation

After analyzing the measurement model (outer

model), the structural model analysis (inner model)

was carried out in the initial test with a 5%

significance level. Finally, the Goodness of Fit (GoF)

is used to evaluate the measurement and structural

models and provides a simple measure of the overall

model prediction. The GoF value was 0.554, which is

included in the large category.

After that, hypothesis testing was carried out by

looking at the PLS results of the path coefficient

section, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: The Initial Path Coefficients of Community

Resilience.

Variable

Original

Sample

(O)

t-

Statist

ics

H

0

Conclu

sion

Economic

aspect on

community

resilience

0.552 1.631 Accepted

Not

signifi

cant

Social aspect

on community

resilience

0.714 5.972 Rejected

Signifi

cant

Cultural aspect

on community

resilience

0.671 5.238 Rejected

Signifi

cant

Human

resource aspect

on community

resilience

-0.101 0.547 Accepted

Not

signifi

cant

Ecological

aspect on

community

resilience

0.761 5.639 Rejected

Signifi

cant

Physical aspect

on community

resilience

0.464 3.284 Rejected

Signifi

cant

Political aspect

on community

resilience

0.231 0.892 Accepted

Not

signifi

can

t

Technological

aspect on

community

resilience

-0.310 1.185 Accepted

Not

signifi

cant

Next, several other models were tested to meet all

the criteria for a match between the model and the

research data. Finally, we modified the model by

removing invalid indicators and dimensions with no

significant effect on community resilience, namely

economic, human resource, political, and

technological aspects, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The Final Path Coefficients of Community

Resilience.

Community Resilience Analysis on Displaced Residents now Living in Rusunawa Marunda

549

The Goodness of Fit (GoF) is used to evaluate the

measurement and structural models and provides a

simple measure of the overall model prediction. The

GoF value was 0.557, which is included in the large

category.

After that, hypothesis testing was carried out by

looking at the PLS results of the path coefficient

section, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: The Final Path Coefficients of Community

Resilience.

Variable

Original

Sample

(

O

)

t-

Statis

tics

H

0

Conclu

sion

Social

aspect on

community

resilience

0.748 5.671 Rejected

Signi

ficant

Cultural

aspect on

community

resilience

0.687 5.265 Rejected

Signi

ficant

Ecological

aspect on

community

resilience

0.773 8.341 Rejected

Signi

ficant

Physical

aspect on

community

resilience

0.478 3.299 Rejected

Signi

ficant

Table 2 confirms the following. First, the social

aspect significantly affects community resilience

with a t-statistic of 5.671, which is bigger than 1.96

(5.671 > 1.96). Second, the cultural aspect

significantly affects community resilience with a t-

statistic of 5.265, which is bigger than 1.96 (5.265 >

1.96). Third, the ecological aspect significantly

affects community resilience with a t-statistic of

8.341, which is bigger than 1.96 (8.341 > 1.96).

Finally, the physical aspect significantly affects

community resilience with a t-statistic of 3.299,

which is bigger than 1.96 (3.299 > 1.96).

Our findings confirmed that the most dominant

aspect that formed community resilience of displaced

residents living in Rusunawa Marunda was the

ecological aspect (R-square of 0.597 or 59.7%). It

was followed by the social aspect (R-square of 0.559

or 55.9%), the cultural aspect (R-square of 0.472 or

47.2%), and the physical aspect (R-square of 0.229 or

22.9%).

Figure 3: The Dominant Aspects that Formed Community

Resilience of Displaced residents Living in Rusunawa

Marunda.

We ended up with only four (4) out of eight (8)

aspects that formed the community resilience of

displaced residents living in Rusunawa Marunda.

This finding rejected the initial assumptions of the

initial model that used eight (8) aspects as the

hypothesis (economic, social, cultural, human

resources, ecology, physical, political, and

technological aspects). Furthermore, our findings

contradict previous studies because they used

different traumatic events from our study that used

relocation of people living on the government’s land

(open green space) illegally. For example, Longstaff

(2010) examined the effect of disaster and terrorism

events on community resilience. Ajita and Howard

(2016), Roger (2016), Barrow Cadbury Trust (2012),

and British Red Cross ( 2013) examined the effect of

disaster events. In addition, Schwind et al. (2009)

examined the effect of economic crisis.

The relocation has been a political will

positioning the now-residents of Rusunawa Marunda

as the subject of development; thus, the respondents

felt that the political aspect was the primary cause for

their traumatic experience of being relocated. The

effect of the relocation as a traumatic event was that

the people felt that the government intentionally and

consciously changed the people’s fate. Thus, the

displaced residents now living in Rusunawa Marunda

see any assistance or programs the government offers

to help them adapt and continue their lives

meaningless and could not give them the same life

they used to have. To sum up, the displaced residents

now living in Rusunawa Marunda did not consider

the political aspect crucial in forming community

iCAST-ES 2022 - International Conference on Applied Science and Technology on Engineering Science

550

resilience, which contradicts the results of previous

studies.

The displaced residents now living in Rusunawa

Marunda also did not see the economic aspect as

necessary for their resilience. It happened because

they had lower income than they used to before

relocation. In addition, although they paid less to live

in Rusunawa than they used to, the people believed

they spent more on daily needs than before. This

happened because the relocation had forced them to

leave their previous business behind, such as selling

goods and working in entertainment centers, making

them lose their livelihoods. Since these people only

had the skill of sellers or trades in economic centers,

the technological and human resource aspects were

not needed in forming resilience in their new place

because Rusunawa Marunda is not a center of

economic or entertainment activities. In addition,

they spent less in their previous home because they

lived illegally without paying rent—they also got the

water service and electricity illegally.

Natural resource quality, equity, natural resource

utilization, and diversity dominate ecological aspects.

The displaced residents now living in Rusunawa

Marunda perceived that water quality and service,

environment, and household waste disposal and

sanitation are better than in their previous residential

under the roads and/or near river banks.

Connectedness is the dominant indicator in

shaping the social aspect than the organizational

indicator. For example, although housing placement

is done randomly, respondents from the relocation

area found it comfortable hanging out with their

neighbors because they were well received. For

organizational indicators, the involvement of the

majority of residents in social organizations was

because they found the organizations fulfilled their

needs, such as religious services, community

services, sports, social gatherings, skill development,

and waste banks. Barrow Cadbury Trust (2012)

mentions that connectedness can shape community

resilience.

In the cultural aspect, value conformity and

comfort were more dominant than new habits.

Respondents felt calmer and more comfortable

because they lived in a decent house and could better

follow the growth of their children. Children could

actively play in a good place. Residents were

involved in various social activities.

The physical aspect in sequential was formed by

health, education, market, worship, work and

recreation facilities. According to respondents,

Rusunawa Marunda provided complete and

affordable physical facilities. In addition, a play area

for children helped the displaced residents, especially

parents, feel secure knowing that their children

played in a safe place, especially those previously

living in the Kalijodo area.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study analyzes the community resilience of the

displaced residents now living in Rusunawa

Marunda. Our findings confirmed only four (4) out of

eight (8) aspects forming the community resilience of

these displaced residents in Rusunawa Marunda. Our

finding differed from previous studies because we

used different traumatic events, namely relocation of

people living illegally on the government’s land

(open green space). Previous studies examined the

effect of disaster and terrorism (Longstaff, 2010;

Howard, 2016; Roger, 2016; Barrow Cadbury Trust,

2012; British Red Cross, 2012) or economic crisis on

community resilience (Schwind et al., 2009).

The community resilience of the displaced

residents now living in Rusunawa Marunda was

formed by the ecological aspect, especially water

quality and service, environment, and household

waste disposal and sanitation that were better than in

their previous residential under the roads and/or near

river banks. The social, cultural, and physical aspects

were the dominant aspects after the ecological aspect

for community resilience.

The political aspect, such as aspiration and

government assistance, was not perceived as an

essential or dominant aspect of forming community

resilience of these displaced residents. The economic,

technological, and human resource aspects were also

not seen as crucial in forming community resilience

in Rusunwa Marunda. They had to pay more expense

living in Rusunawa for rent, electricity, and water—

all things they could get illegally before moving to

Rusunawa. However, they made less money because

they no longer lived in the economic and

entertainment centers where they could work freely—

Rusunawa is a housing complex, not an economic

center. Many people who used to work without

specific skills were forced to leave such unskilled

jobs when moving to Rusunawa Marunda—they

could neither use their capacity nor the technology

available to improve their capacity.

REFERENCES

Aditya B, Emma L, Emily W, and Thomas T. 2015.

Resilience in the SDGs: developing an indicator for

Community Resilience Analysis on Displaced Residents now Living in Rusunawa Marunda

551

target 1.5 that is fit for purpose. Shaping policy for

development. Overseas Development Institute.

London, UK /Odi.org

Ajita Atreya and Howard Kunreuther. 2016. Measuring

community resilience: the role of the community rating

system (SRS). Risk management and decision processes

center, the Wharton School, University Pennsylvania,

USA

Barrow Cadbury Trust. 2012. Adapting to change: the role

of community resilience. The Young Foundation, UK

Berkes F, J Colding, and C Folke. 2003. Navigating social-

ecology systems: building resilience for complexity and

change. Cambridge university press, Cambridge, UK

British Red Cross-International federation of red cross and

red crescent societies. 2013. Options for including

community resilience in the post-2015 development

goals. Geneva, Switzerland

Christenson JA, K Fendley and JW Robinson Jr. 1989.

Community development in perspective. USA: IOWA

State University Press

Demographia. 2019. Demographia World Urban Area 15

th

annual report 2019 (Built-up urban area or world

agglomeration)

Hair Jr, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., and Sarstedt, M.

2016. A primer on partial least squares structural

equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage publications.

Kompas.com. 2015. Permasalahan Sosial-Ekonomi Warga

Rusunawa Tengah Dikaji Artikel ini telah tayang

https://megapolitan.kompas.com/read/2015/12/01/155

52751/Permasalahan.Sosial-

Ekonomi.Warga.Rusunawa.Tengah.Dikaji. Diakses

pada 14 Maret 207

Kraas, F., and Mertins, G. 2014. Megacities and global

change. In Megacities (pp. 1-6). Springer, Dordrecht.

Longstaff, Patricia H., Nicholas J.Amstrong, Keil Perrin,

Whitney M.P., Matthew A H. 2010. Building Resilient

Communities: a Preliminary Framework for

Assessment. Homeland security affairs, Vol VI, No.3

Mankiew, N.G., 2006. The macroeconomist as a scientist

and engineer. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(4),

pp.29-46.

Pravitasari, A.M. 2018. Dampak Urbanisasi dan

Perkembangan Perkotaan di Jabodetabek dan

Sekitarnya serta Pengaruhnya pada Peningkatan

Degradasi Lingkungan

Roger Blakeley. 2016. Building community resilience:

report prepared for NZ society of local government

managers (SOLGM). New Zealand.

Runtunuwu, S., Antariksa, S., Surjono, Ismu R. D. A.,

2018, The Conceptual Framework of Community

Resilience of the Flat Residents. International Journal

of Engineering and Technology, 7 (4.40) (2018) 172-

178, Website: www.sciencepubco.com/index.php/IJET

Schwind, K., Localize, B., Cordova, L., Goldberg, L.,

and Salzman, S. 2009. Community Resilience

Toolkit. Oakland: Bay Localize. Accessed May 29, 2015

UNESCAP. 2016. Building e-resilience: Enhancing the

role of ICTs for Disaster Risk Management (DRM).

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for

Asia and the Pacific. ICT and Development Section.

USAID. 2013. The resilience agenda: measuring resilience

in USAID. USAID, Washington https://www.usaid.

gov/sites/default/files/documents/1866/Technical%20

Note_Measuring%20Resilience%20in%20USAID_Ju

ne%202013.pdf.

Van Breda, A.D., 2001. Resilience theory: A literature

review. Pretoria, South Africa: South African Military

Health Service.

Wilhelm, M. 2011. Approaching disaster vulnerability in a

megacity: community resilience to flooding in

two kampungs in Jakarta. Unpublished doctoral

dissertation). University of Passau, Achen.

Zatura, A. 2009. “Resilience: One part recovery, two part

of sustainability”, Journal of Personality, vol/issue:

77(6), pp. 1935-1943.

iCAST-ES 2022 - International Conference on Applied Science and Technology on Engineering Science

552