The Analysis of Test-Taking Anxiety from a Sample of Chinese

Students Studying Abroad and in the Home Country

Rihua Min

1,*,+ a

, Tianyu Han

2,+ b

and Zhihan Yang

3,+ c

1

College of Arts and Sciences, Syracuse University, 331 Chinook Dr, Syracuse, U.S.A.

2

Nanjing No.9 Middle School, No.51 Beiting Alley, Nanjing, China

3

Changzhou senior high school of Jiangsu Province, No.8 Luohan Road, Changzhou, China

*

Corresponding author

These authors contributed equally

Keywords: Test-Taking Anxiety, Chinese Students, The United States.

Abstract: In light of the high prevalence of anxiety among students and severe test-taking anxiety among Chinese

students, one of our main purposes is to discuss whether studying abroad in the United States could relieve

test-taking anxiety, and we thus merely recruited participants who were Chinese to test hypotheses.

Participants in our experiment were N = 44 Chinese students (age range: 16-24 years, 33 females and 11

males) recruited from multiple high schools and universities across China and the United States. After a

comprehensive and comparative analysis, we found that Chinese students studying abroad had less test-taking

anxiety than those studying in their home country China.

Test forms (test with or without rewards) had no

relationship with test-taking anxiety and no interaction with countries for study. The relationship between

test-taking anxiety and test scores was largely negative. According to our findings, however, there was no

relationship between gender and test-taking anxiety.

1 INTRODUCTION

Mental illness, as a prevalent issue among students,

has a negative relationship with academic

performance. Of college students, 25 % have been

diagnosed with or been treated for mental health

illnesses (Posselt, & Lipson, 2016). Posselt and

Lipson (2016) also claimed that anxiety, a form of

mental illness, is one of the top factors that impair the

academic achievements of college students.

Similarly, of middle and high school students in

Shanghai, 28.3% were tested as abnormally anxious

(Gu, Gong, & Zhang, 2009). Taking tests is a process

every student will experience in their school lives, but

what is its relationship with anxiety needs to be

explored. Contemplating multiple causes that give

rise to anxiety is imprudent and complicated, thus

focusing on test-taking concerning anxiety is our aim.

China and the United States, because of their

different cultural and educational patterns, bring

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0064-7544

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0720-0251

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8619-3565

about discrepant influences on students. However, the

students in both countries might have more or less

pressure and anxiety caused by tests in common.

Test-taking anxiety of Chinese students has been a

hot issue in Chinese society for many years and even

attracted the attention of the world because of the

severe pressure of study and examination brought by

the exam-oriented education system. The prevalence

of anxiety symptoms among middle and high school

students in China reaches 9.89% (Xu, Mao, Wei, Liu,

Fan, Wang, Wang, Lou, Lin, Wang, & Wu, 2021).

One of our main purposes is to discuss whether

studying abroad in the United States could relieve

test-taking anxiety, and we thus merely recruited

participants who were Chinese to test hypotheses.

Owing to the deficiency of research on test-taking

anxiety, we list a bunch of hypotheses and try to

discover the potential factor connected to test-taking

anxiety, including gender, test forms, test scores, and

the goal of the test. Our main method for

394

Min, R., Han, T. and Yang, Z.

The Analysis of Test-Taking Anxiety from a Sample of Chinese Students Studying Abroad and in the Home Country.

DOI: 10.5220/0011912700003613

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on New Media Development and Modernized Education (NMDME 2022), pages 394-402

ISBN: 978-989-758-630-9

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

measurement was Form Y-1 from State-Trait Anxiety

Inventory (STAI) (Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene,

Vagg, & Jacobs, 1983). Our participants in the

experiment were all Chinese students, recruited from

multiple high schools and universities across China

and the United States, aged 16-24.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Stowell and Bennett (2010) found that test-taking

anxiety could be reflected by its “affective (physical

arousal, emotionality), cognitive (worry), and

behavioral (procrastination, avoidance)

components”, together impairing the academic

achievement of college students. Zeidner (1998) also

referred to test-taking anxiety as “the set of

phenomenological, physiological, and behavioral

responses that accompany concern about possible

negative consequences of failure on an exam or

similar evaluative situation”. We conceptualize the

reason for test-taking anxiety among Chinese

students in terms of the contemporary goal

classification theory (Elliot, 1999; Pintrich, 2000) and

make hypotheses based on prior research findings.

2.1 Contemporary Goal Classification

Theory

According to the contemporary goal classification

theory proposed by Elliot (1999) and Pintrich (2000),

learning goals can be divided into 4 major types:

mastery approach goal -- the purpose of personal

participation in activities is seeing their progress and

improvement; mastery avoidance goal -- the purpose

of personal participation is to avoid their

shortcomings actively; performance-approach goal --

the purpose of personal participation in activities is to

expect a positive evaluation of the outside world;

performance-avoidance goal -- the purpose of

personal participation in activities is to avoid the

negative evaluation of the outside world. Concluded

from their later findings, Linnenbrink and Pintrich

(2000) associated learning goals with anxiety as

follows: mastery approach goal is associated with low

anxiety, mastery avoidance goal and performance-

approach goal are related to moderate anxiety, and the

performance-avoidance goal is correlated with high

anxiety.

Because the educational system in China is exam-

oriented, every test is highly valued by Chinese

students as an assessment of their self-esteem. As a

result, test-taking anxiety escalates in the preparation

of the test. Given the previous investigation in high

schools, test-taking anxiety was a common problem

among Chinese students. Of the students who were

anxious about tests, 74.8% had moderate or severe

test-taking anxiety, and showed strong performance-

avoidance goals and performance-approach goals; the

rest (25.2%) with mild anxiety mostly showed

mastery avoidance goals, and a small number of them

showed the other three goals (Cui, Liu, & Gao, 2008).

In addition, a study on Chinese college students

revealed that the anxiety level of college students was

concentrated in the low and middle levels, lower than

that of middle school students. Their learning goals

were mainly embodied as mastery approach goal,

mastery avoidance goal, and performance-approach

goal, which are associated with low and moderate

anxiety (Wang, 2013).

There are some similarities and differences in test-

taking anxiety between Chinese and American

students, as evidenced by previous studies. For both

Chinese and American students, taking the foreign

language test in Chinese and American colleges

students, for example, the learning goals leading to

their test-taking anxiety are comparable. In terms of

learning goals, American students experience test-

taking anxiety because they are concerned about the

failure of the application of examinations to life and

the negative evaluation from others, whereas the test-

taking anxiety of Chinese students is only reflected in

the fear of negative evaluation from others (Tang,

2012). However, as per one research on test-taking

anxiety of high school students in China and the

United States, the learning goals leading to test-taking

anxiety among students in the two countries are

different. Chinese students are more worried about

the negative evaluation from peers, parents, teachers,

and people from the outside world if they fail the

exam, while American students are merely concerned

about their test performance not being able to be

employed in real life pragmatically and the test failure

may harm their chance of further study (Huang,

Huang, Xing, Sanche, & Ye, 2005).

2.2 Competition

Posselt and Lipson (2016) argued the sense of

competition highly increases the incidence of test-

taking anxiety among students. They are afraid of bad

test performance and its subsequent negative

outcome, which brings about tremendous anxiety.

2.3 Gender

In terms of gender, female students had higher

anxiety levels than male students because of greater

The Analysis of Test-Taking Anxiety from a Sample of Chinese Students Studying Abroad and in the Home Country

395

emotional fluctuations (Li, & Liu, 1999). According

to a survey of high school students (Huang, 2003), the

degree of test-taking anxiety of girls was significantly

higher than that of boys, and the number of girls who

had severe and moderate anxiety is much more than

boys. Surprisingly, in another middle school, the

degree of anxiety of female students is almost the

same as (slightly higher than) that of male students.

The anxiety of boys comes primarily from parents’

high expectations, while that of the girls is produced

mostly from the negative self-cognition caused by

examinations and the pressure from school and

society (Wang, Lu, Chen, & Xia, 2005).

2.4 Test Performance

Many research findings have demonstrated that test-

taking anxiety greatly lowers test performance

(Chapell, Blanding, Silverstein, Takahashi, Newman,

Gubi, & McCann, 2005; Barrows, Dunn, & Lloyd,

2013; Posselt, & Lipson, 2016; Gharib, Phillips, &

Mathew, 2012; Stowell, & Bennett, 2010; Cassady, &

Johnson, 2002; Zeidner, 1998). In a study with 5551

participants who completed STAI (Spielberger et al.,

1983) and reported their cumulative GPA and grades,

there was “a one-third letter grade difference between

undergraduates with high test anxiety and lower test

anxiety” (Chapell et al., 2005). Likewise, Barrows et

al. (2013) pointed out that 10 million primary and

secondary students performed badly in tests due to

their test-taking anxiety.

2.5 Psychopathology

Anxiety disorder increasingly happens to students. In

the study at Uludag University, among 4850 students,

29.6% and 36.7% obtained the anxiety scores from

the evaluations of STAI Form Y-1 (state anxiety) and

Y-2 (trait anxiety), respectively (Spielberger et al.,

1983), higher than the cut-off point of

psychopathology, which means they might have an

anxiety disorder (Ozen, Ercan, Irgil, & Sigirli, 2010).

2.6 Hypotheses

Given the contemporary goal classification theory

and previous literature, we make the following

hypotheses:

H1: There would be some differences in test-

taking anxiety between Chinese students studying

abroad in the United States and the home country

when taking a test with or without rewards (the

reward might somehow provoke a sense of

competition).

H2: Female students would have higher test-

taking anxiety than male students.

H3: There would be some differences in test

scores between Chinese students studying abroad in

the United States and the home country when taking

a test with or without rewards.

H4: Test-taking anxiety would have a negative

relationship with test scores.

Besides, we would not only analyze the

relationship between the goal of the test and test-

taking anxiety but compare the incidence of anxiety

disorder before and after the awareness of the

existence of a test. We only focus on Chinese students

as our participants to control variables and observe

whether studying abroad in the United States could

alleviate test-taking anxiety, thus further proving the

success of the American educational pattern in terms

of the alleviation of test-taking anxiety.

3 METHOD

3.1 Participants and procedure

Participants in our experiment were N = 44 Chinese

students (age range: 16-24 years, 33 females and 11

males) recruited from multiple high schools and

universities across China and the United States. Of

them, N = 24 had been studying abroad in the United

States for at least 2 years and N = 20 studied in their

home country China (they had never been to foreign

countries including the United States). They all

signed a consent form before being asked to

participate. To ensure those Chinese students who

studied abroad had assimilated American cultural and

educational patterns, we set the threshold 2 years in

the United States; likewise, Chinese students who

studied in the home country were set the threshold as

having never been to foreign countries to prevent

them from contacting foreign cultural and educational

patterns. While they were found fit for the

requirements, we contacted them through either email

or WeChat (a Chinese social media) in favor of their

preference. Then the participants were divided into

four groups: students who studied abroad took a test

with a reward; students who studied abroad took a test

without a reward; students who studied in the home

country took a test with a reward; students who

studied in the home country took a test without

reward. To simulate a real test environment, we

arrange all participants in each group within one

setting.

Our experiment consists of two STAI (Form Y-1)

(Spielberger et al., 1983) questionnaires, one in the

NMDME 2022 - The International Conference on New Media Development and Modernized Education

396

very beginning (without knowing the existence of a

test) and the other one just before taking the test

(knowing the existence of a test), a test asking basic

questions (the difficulty is set the same as that of

middle school in China) that costs 7 minutes, and a

questionnaire for debriefing. The experiment was

conducted on Zoom, an online meeting app, thus it

was conducted in a video-conferencing format. All

participants attended the meeting punctually and

opened cameras throughout the whole experiment. N

= 8 participants wore a mask in the process. The

experiment on average lasted for 25 minutes for each

group.

3.2 Instruments

Two STAI questionnaires (created on Qualtrics) were

assessed using the same but randomized 20 items

from Form Y-1 to measure state anxiety (Spielberger

et al., 1983). To avoid the language barrier, a

Chinese-version STAI was utilized by attaching the

Chinese translation to each item and prompt (Wang,

Wang, & Ma, 1999). The items were administrated

with a four-point rating scale, ranging from not at all

(1) to very much so (4) for the negative term (e.g., I

feel tense). The order of points for each item was

reversed for the positive term (e.g., I feel secure). We

subtracted the first state anxiety score (one in the very

beginning) from the second one (one just before

taking the test) to measure how much anxiety induced

by a test (i.e., test-taking anxiety equaled the second

state anxiety score minus the first state anxiety score).

The rewards for the test were random delicate gifts.

The test (created by Wenjuanxing, a Chinese

survey maker) in the experiment included 13

questions with the full marks as 100 -- 10 multiple-

choice questions (each was worth 6 points), 2

multiple-answer questions (each was worth 13 points,

and partial credits, 6 points, were allowed only if

getting one choice wrong), and 1 short-answer

question that was worth 14 points. Questions were

interdisciplinary, given from tests of middle school

(age 14) in China. There were four test papers for four

groups of participants and participants in each group

would do the same test paper.

Test Examples:

Multiple-choice question: In a hexagon, the

sum of degrees of interior angles is …

a. 360

b. 720

c. 860

d. 1080

Multiple-answer question: Which of the

following is not able to conduct electricity?

a. Iron

b. Pure water

c. Graphite

d. Human bodies

e. Silicon

f. Air

Short-answer question: Why do women

annually earn less money than men on average?

The questionnaire (also created on Wenjuanxing)

for debriefing asked participants to be debriefed on

their feelings before and after the test. In addition,

they were requested to indicate their goal of the test.

Questions were all set open-ended.

3.3 Analyses

Regarding the first and third hypotheses, we

computed a 2×2 Between-Subjects ANOVA for each.

Concerning the second hypothesis, we computed an

independent-samples t-test. While for the fourth

hypothesis, we made a correlation analysis. To reach

coherence and consistency in analyses, we set the

critical region in all tests α = .05. Then for the fifth

hypothesis, we compared the descriptive statistics,

based on test-taking anxiety scores and debriefings,

and made an analysis. Lastly, for the sixth hypothesis,

we computed the anxiety scores of Chinese students

before and after knowing the existence of the test and

then compared them with the cut-off point of 40 to

find the probable number of Chinese students who

could be diagnosed with anxiety disorder arising from

the test (Womble, Jennings, Schatz, & Elbin, 2021).

Our data was all collected in Microsoft Excel and

evaluated in JASP.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Test-Taking Anxiety VS Countries

for Study VS Test Forms

Descriptive Statistics are shown in Table 1. A 2×2

Between-Subjects ANOVA revealed a statistically

significant main effect of countries for study. Chinese

students who study abroad (N = 24) experienced less

test-taking anxiety (M = -.42, SD = 8.36) than those

who study in the home country (N = 20, M = 10.05,

SD = 15.93), F

(1, 40)

= 7.63, p < .01, η

2

p

= .16.

Regarding test forms, analyses revealed that the main

effect was not statistically significant, F

(1, 40)

< .01, p

= .97, η

2

p

< .01. With respect to the interaction

between countries for study and test forms, analyses

revealed a not significant interaction effect, F

(1, 40)

=

1.03, p = .32, η

2

p

= .32. For further analyses of the

The Analysis of Test-Taking Anxiety from a Sample of Chinese Students Studying Abroad and in the Home Country

397

relationship between countries for study and test-

taking anxiety among Chinese students, an

independent-samples t-test indicated that Chinese

students who study abroad had lower test-taking

anxiety than those who study in the home country, t

(42)

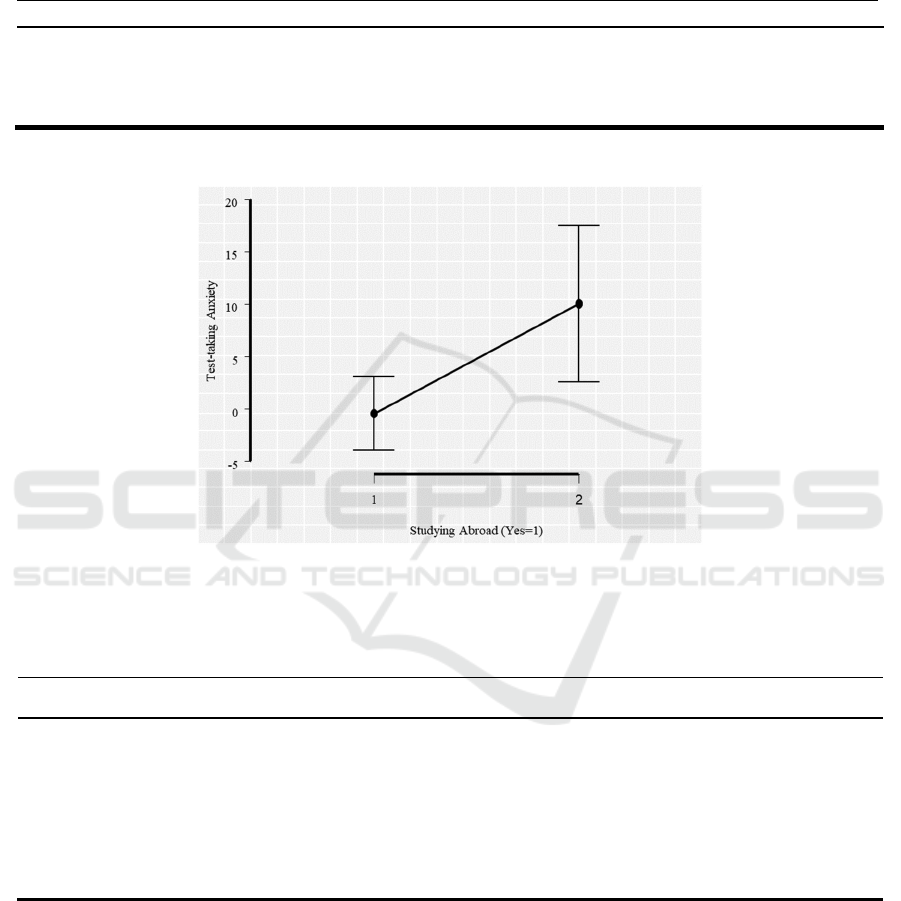

= -2.79, p = .01 (see Figure 1).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of test-taking anxiety for four groups of Chinese students

Countries for study Test Forms M SD N

Studying abroad Test with reward 1.583 5.282 12

Test without reward -2.417 10.457 12

Studying in the home country Test with reward 8.200 14.748 10

Test without reward 11.900 17.629 10

Note. Descriptive statistics of test-taking anxiety based on STAI (Form Y-1) index for four groups of Chinese students

aged 16-24.

Figure 1. The relationship between countries for study and test-taking anxiety among Chinese students aged 16-24 was

established by an independent-samples t-test. The horizontal axis indicated countries for study, which used “number 1” to

denote Chinese students who study abroad and “number 2” to denote those who study in the home country.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of test scores for four groups of Chinese students

Countries for Study Test Forms M SD N

Studying abroad Test with reward 48.000 16.564 12

Test without reward 48.083 16.714 12

Studying in the home country Test with reward 40.900 15.242 10

Test without reward 42.000 15.362 10

Note. Descriptive statistics of test scores based on four test papers, with interdisciplinary questions within the time limit

of 7 minutes for each one, for four groups of Chinese students aged 16-24.

NMDME 2022 - The International Conference on New Media Development and Modernized Education

398

Figure 2. Correlation between test-taking anxiety and test scores among Chinese students aged 16-24 (N = 44).

4.2 Test-Taking Anxiety VS Gender

An independent-samples t-test revealed that there was

no relationship between gender (33 females and 11

males) and test-taking anxiety, t

(42)

= -.55, p = .58. The

effect size was relatively small, Cohen’s d = -.19.

4.3 Test Scores VS Countries for Study

VS Test Forms

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics mainly

focused on test scores. A 2×2 Between-Subjects

ANOVA revealed that in regard to countries for

study, there was no statistically significant main

effect, F

(1,40)

= 1.84, p = .18, η

2

p

= .04. Likewise, the

main effect of test forms was not statistically

significant, F

(1,40)

= .02, p = .90, η

2

p

< .01. There was

also no significant interaction between countries for

study and test forms, F

(1,40)

= .01, p = .92, η

2

p

< .01

.

4.4 Test-Taking Anxiety VS Test

Scores

In the sample of 44 Chinese students, the relationship

between test-taking anxiety and test scores was

Pearson’s coefficient r

(42)

= -.49, p < .01. This

negative relationship was nearly large. Results

showed that 24% of the variability in test scores was

determined by test-taking anxiety, r

2

= .24 (see Figure

2).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of goal types of the test for four groups of Chinese students

Levels of anxiety

Goal types

Studying in the home

country

Studying abroad Total

M SD N M SD N M SD N

Mastery approach goal

35.17 7.06 6 35.22 7.67 9 35.20 7.43 15

Mastery avoidance goal

43.57 10.94 7 41.50 7.50 4 42.82 9.88 11

Performance approach goal

58.00 12.75 4 45.25 8.93 8 49.50 11.98 12

Performance avoidance goal

69.00 4.97 3 67.00 6.38 3 68.00 5.80 6

Note. Descriptive statistics of test-taking anxiety based on STAI (Form Y-1) index and debriefings on Wenjuanxing for

four groups of Chinese students aged 16-24.

4.5 Test-Taking Anxiety VS Goal of the

Test

Through the comparison of research data, the analysis

revealed that the mastery approach goal would cause

the lowest test-taking anxiety among Chinese

students (N

total

= 15, M

total

= 35.20, SD

total

= 7.43),

while the performance-avoidance goal would lead to

their highest test-taking anxiety (N

total

= 6, M

total

=

68.00, SD

total

= 5.80) (see Table 3).

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

-40-30-20-100 102030405060

Test Scores

Test-Taking Anxiety

The Analysis of Test-Taking Anxiety from a Sample of Chinese Students Studying Abroad and in the Home Country

399

4.6 Anxiety Disorder

At the beginning of the experiment (without knowing

there would be a test), 18 out of 44 (40.9%) Chinese

students obtained the anxiety scores from STAI

(Form Y-1) above the cut-off point of

psychopathology, which meant they could be

diagnosed with anxiety disorder in a clinical setting

(Womble et al., 2021). Yet just before taking the test

(after knowing there would be a test), 6 more Chinese

students (N = 24 in total, 54.5%) were tested above

the cut-off point of psychopathology.

5 DISCUSSION

Given the results, our first and fourth hypotheses were

validated whereas the second and third were falsified.

More specifically, the first hypothesis was partly

validated: the only found difference was that Chinese

students studying abroad had less test-taking anxiety

than those studying in their home country China. Test

forms, however, had no relationship with test-taking

anxiety and no interaction with countries for study.

We assume one reason is our participants were

somewhat immune to physical rewards because of

their high socioeconomic status (Chen, & Hou, 2014).

Another reason could be they were motivated by the

physical rewards, contrary to our supposition, to

compete more passionately, lowering test-taking

anxiety (Chen, & Hou, 2014). The result might have

been altered if we either enhanced the price of

physical rewards or converted the form of rewards to

the psychological.

There was no relationship between gender and

test-taking anxiety and no difference in test scores

between Chinese students studying abroad in the

United States and in the home country when taking a

test with or without rewards. Our findings were

inconsistent with any other previous research

findings. One possible reason is the size of our sample

was not sufficiently large.

The relationship between test-taking anxiety and

test scores was largely negative, which was consistent

with other research findings and perfectly verified our

fourth hypothesis.

Our result also confirmed the findings of

Linnenbrink and Pintrich (2000): mastery approach

goal will cause the lowest level of anxiety, mastery

avoidance goal and performance-approach goal will

induce moderate anxiety level, while performance-

avoidance goal will lead to the highest level of

anxiety among Chinese students.

When Chinese

students studying abroad in the United States and

studying in their home country faced exams, all four

types of goals were involved. Among them, the

number of students with the type of mastery approach

goal was the largest. The fewest number of students

had the performance-avoidance goal. This was not

consistent with the result of the previous study on

Chinese high school students, (Cui et al., 2008) but

similar to that of a previous investigation of Chinese

college students (Wang, 2013). The reason might be

the test in the experiment did not have a significant

impact on student's personal development. Students

thus would not focus too much on test scores and not

worry about negative results and evaluations and

would turn to improve their abilities instead.

Further, the result revealed that in any case from

the contemporary goal classification theory, the test-

taking anxiety of Chinese students studying abroad in

the United States was slightly lower than that of those

studying in the home country, and in the case of

performance-approach goals, the test-taking anxiety

of Chinese students who studied abroad to the United

States (M = 45.25) was significantly lower than that

of those who studied in the home country (M =

58.00). It was assumed that when both two cohorts

wanted to be positively evaluated by the outside

world because American culture emphasizes the

cultivation of self-confidence more than Chinese

culture, Chinese students who studied abroad in the

United States could be more likely to draw upon self-

confidence to cope with test-taking anxiety.

In previous studies, mastery avoidance goals and

performance-approach goals were associated with

moderate anxiety. However, these studies had not

indicated the specific difference between the levels of

anxiety arising from the two goals. Following our

experiment, the difference between the anxiety levels

triggered by these two goals was offered – the anxiety

caused by performance-approach goal was higher

than that caused by mastery avoidance goal. This

point was rarely mentioned in previous studies. The

result of our experiment could fill the gap in previous

studies.

Not surprisingly, the number of students probably

having anxiety disorder after the awareness of the

existence of a test was more than before. However,

the proportion of students diagnosed with anxiety

disorder (40.9% before and 54.5% after), according

to the scale of anxiety scores from STAI Form Y-1

(Spielberger et al., 1983) and the cut-off point of

psychopathology as 40 (Womble et al., 2021), was

much higher than our expectations and previous

research findings. Our explanation for it is that the

online setting and COVID-19 pandemic complicates

NMDME 2022 - The International Conference on New Media Development and Modernized Education

400

their mental state, which would be mentioned in the

following section.

6 LIMITATIONS

There are some limitations worth taken into

consideration when interpreting our results. First, the

online setting might affect test-taking anxiety levels

of certain students. Test-taking anxiety is not

uncommon among students in online exam

environment (Huang, 2014). Online learning and tests

could bring students visual fatigue, mental

depression, loneliness, and many other negative

experiences (Li, & Fu, 2013). Stowell and Bennett

(2010) found that experiencing less anxiety in one

form of test entails higher anxiety in another form of

test; in other words, those who feel comfortable in

classroom settings would feel anxious when taking

online tests and the inverse is also correct. The online

setting could be one factor elevating test-taking

anxiety of some students to the overestimated value,

otherwise it lowered test-taking anxiety of several

students who were in favor of online tests.

In the midst of the period of pandemic COVID-

19, the score of acute psychological stress among

international students were higher than general

population. Because international students had to

undergo the inconvenience of living in isolation,

away from family and home, cultural differences,

academic delays, and visa issues, their anxiety levels

were elevated above normal amid the period of

COVID-19 (Zhao, 2022). Despite these troubles, the

cohort in our experiment – Chinese students studying

abroad to the United States – experienced

significantly less test-taking anxiety than Chinese

students studying in the home country China.

Whether COVID-19 was involved in the result or not

was unknown and further studies should be taken into

account.

Also, two years as a threshold to distinguish

Chinese students studying abroad to the United States

from those studying in the home country China might

be arbitrary. Whether adjusting the threshold would

have changed the result remains unclear. Lastly, as

said, our sample size was not large enough, so some

of our results might be affected.

7 CONCLUSIONS

Concluded that Chinese students studying abroad had

less test-taking anxiety than those studying in the

home country China; test forms (test with or without

rewards) had no relationship with test-taking anxiety

and no interaction with countries for study; there was

no relationship between gender and test-taking

anxiety; there was no difference of test scores

between Chinese students studying abroad to the

United States and in the home country when taking a

test with or without rewards; the relationship between

test-taking anxiety and test scores was largely

negative. Moreover, we also found that in any case

from the contemporary goal classification theory, the

test-taking anxiety of Chinese students studying

abroad in the United States was slightly lower than

that of those studying in the home country, and in the

case of performance-approach goals, the test-taking

anxiety of Chinese students who studied abroad to the

United States was significantly lower than that of

those who studied in the home country.

By our experiment in the video-conferencing

form, anxiety probably caused by COVID-19,

relatively small sample size, and arbitrary selection of

participants, our results might be affected. Therefore,

further studies that prudently consider these

conditions are highly needed and we would do some

of them in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are thankful to the precious advice given by

Hanna, a Chinese teacher, when we formulated ideas

of this research and the commitment of Ge Gao, a

Sophomore at Syracuse University, to the data

collection. We appreciate their contributions to the

research.

REFERENCES

Barrows, J., Dunn, S., & Lloyd, C. A. (2013). Anxiety, self-

efficacy, and college exam grades. Universal Journal of

Educational Research, 1(3), 204-208.

Cassady, J. C., & Johnson, R. E. (2002). Cognitive test

anxiety and academic performance. Contemporary

Educational Psychology. 27(2), 270–295.

Chapell, M. S., Blanding, Z. B., Silverstein, M. E.,

Takahashi, M., Newman, B., Gubi, A., & McCann, N.

(2005). Test anxiety and academic performance in

undergraduate and graduate students. Journal of

Educational Psychology, 97(2), 268-274.

Chen, P., & Hou, C. (2014). Simple analysis of the

complementary motivations induced by physical and

spiritual rewards among university students. Journal of

Yangtze University (Social Sciences), 37(12), 153-155.

The Analysis of Test-Taking Anxiety from a Sample of Chinese Students Studying Abroad and in the Home Country

401

Cui, N., Liu, Y., & Gao, B. (2008). The relationship

between achievement goal, examining anxiety and

performance in senior students. China Journal of Health

Psychology, 16(4), 436-438.

Elliot, A. J. (1999). Approach and avoidance motivation

and achievement goals. Educational Psychologist,

34(3), 169-189.

Gharib, A., Phillips, W., & Mathew, N. (2012). Cheat sheet

or open-book? a comparison of the effects of exam

types on performance, retention, and anxiety.

Psychology Research, 2(8), 469-478.

Gu, W., Gong, X., & Zhang, W. (2009). A survey of

depression and anxiety among high school students.

Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, (6), 415-416.

Huang, G. (2003). Gender differences in test anxiety of

College Entrance Examination students. Health

Psychology Journal, 11(2), 98-99.

Huang, X. (2014). An empirical study of English computer-

based test anxiety in the network environment. Journal

of Kaifeng Institute of Education, 34(6), 77-79.

Huang, X., Huang, H., Xing, Li., Sanche, K., & Ye, R.

(2005). What do middle school students fear for lower

grades on important examinations: Comparisons of the

United States and China. Journal of Nantong University

(Education Sciences Edition), 21(1), 37-41.

Li, X., & Liu, H. (1999). Study on gender differences in test

anxiety of medical college students. Chinese Journal of

School Health, 21(3), 192-193.

Li, Y., & Fu, G. (2013). Research on factors influencing

college students' online learning anxiety. E-Education

Research, 5, 31-38.

Linnennbrink, E. A., & Pintrich, P. R. (2000). Multiple

pathways to learning and achievement: The role of goal

orientation in fostering adaptive motivation, affect, and

cognition. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The

search for optimal motivation and performance (pp.

195-227). Academic Press.

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). An achievement goal theory

perspective on issues in motivation terminology theory

and research. Contemporary Educational Psychology,

25, 92-104.

Posselt, J. R., & Lipson, S. K. (2016). Competition, anxiety,

and depression in the college classroom: Variations by

student identity and field of study. Journal of College

Student Development, 57(8), 973-989.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushene, R., Vagg, P.

R., & Jacobs, G. A. (1983). Manual for the State-Trait

Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting

Psychologists Press.

Stowell, J. R., & Bennett, D. (2010). Effects of online

testing on student exam performance and test anxiety.

J. Educational Computing Research, 42(2), 161-171.

Tang, J. (2012). A comparative study of foreign language

learning anxiety between Chinese and American

college students. English Teachers, 2, 31-36.

Wang, X., Wang, X., & Ma, H. (1999). Handbook of mental

health assessment scales (Enlarged ed., pp. 205-209).

Chinese Mental Health Magazine Press.

Wang, Y. (2013). The Relationship among college

students’ achievement goal, academic self-efficacy and

test anxiety [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Harbin

Engineering University.

Wang, Y., Lu, X., Chen, S., & Xia, W. (2005). Gender

differences in test anxiety among middle school

students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation,

9(40), 24-26.

Womble, M., Jennings, S., Schatz, P., & Elbin, R. J. (2021).

A-173 clinical cutoffs on the State-Trait Anxiety

Inventory for concussion. Archives of Clinical

Neuropsychology, 36(6), 1228.

Xu, Q., Mao, Z., Wei, D., Liu, P., Fan, K., Wang, J., Wang,

X., Lou, X., Lin, H., Wang, C., & Wu, C. (2021).

Prevalence and risk factors for anxiety symptoms

during the outbreak of covid-19: A large survey among

373216 junior and senior high school students in China.

Journal of Affective Disorders, 288(1), 17-22.

Zeidner, M. (1998). Test anxiety: The state of the art. New

York: Plenum Press.

Zhao, Q. (2022). A Study on acute psychological stress

reaction and coping style of Chinese overseas students

during the COVID-19 pandemic. Chinese Journal of

Frontier Health and Quarantine.

NMDME 2022 - The International Conference on New Media Development and Modernized Education

402