Ukrainian Guest Workers in the Labor Market of Poland:

Changing Trends in Labor Migration Processes

Liudmyla V. Kalashnikova

1 a

, Victoriia O. Chorna

2 b

and Yana V. Zoska

3 c

1

Kryvyi Rih State Pedagogical University, 54 Gagarin Ave., Kryvyi Rih, 50086, Ukraine

2

Petro Mohyla Black Sea National University, 68 Marines Str., Mykolaiv, 54003, Ukraine

3

Mariupol State University, 6 Preobrazhenska Str., Kyiv, 03037, Ukraine

Keywords:

Guest Workers, Labor Migration, Processes, COVID-19, Economic Factors.

Abstract:

The movement of Ukrainian guest workers in the direction of Poland until 2019 was predominantly transna-

tional in nature, as there was a constant movement of labor migrants between the national spaces of Ukraine

and Poland with financial participation in the economies of the two countries at the same time. This fact

is confirmed by the results of empirical sociological researches conducted by the Ukrainian Institute of the

Future, the Cedos analytical agency, the Personnel Service employment agency, the Gremi Personal, and the

statistical data of the International Organization for Migration, the State Migration Service of Ukraine, the

State Statistics Service of Ukraine, the Ministry of Family and Social Development of Poland. However, the

trends changed dramatically due to the global COVID-19 epidemic, later in 2022 with the outbreak of the

war in Ukraine. The desire for temporary, pendulum labor mobility gave way to the desire to leave Ukraine

forever and settle abroad with the whole family. A new migration trend may be associated with the movement

to Poland of Ukrainian men who come after the end of the war to reunite with their families, who were moved

there earlier since the beginning of hostilities in Ukraine.

1 INTRODUCTION

The strengthening of the globalization of economic,

socio-political processes determines the expediency

of studying, both at the theoretical and applied levels,

of subjects, causes, consequences, peculiarities of the

intensification of labor migration processes, the speci-

ficity of which is outlined by socio-spatial and tempo-

ral characteristics. Modern transnational labor migra-

tion processes have socio-economic differences, con-

tribute to the development of the economic infrastruc-

ture of the countries involved in it. At the same time,

they create social problems, exerting an ambiguous

influence on the labor market, the investment climate,

the state of the most important social institutions, and

the foreign and domestic political situation. Changes

in the content and forms of external labor migration

are determined by the nature of the political, admin-

istrative and legal, economic and sociocultural deter-

minants that justify and regulate it.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9573-5955

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6205-7163

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0407-1407

Poland’s accession to the EU in 2004 and acces-

sion to the Schengen area in 2007 contributed to the

elimination of a number of restrictions on the admis-

sion of migrant workers. According to the statis-

tics service for the period 2004–2014. amounted to

about 2.5 million Polish workers to other EU coun-

tries with relatively higher living standards (Minis-

terstwo Spraw Zagranicznych, 2014). Against the

background of successful economic development and

record low unemployment, the Polish labor mar-

ket experienced a shortage of workers, a niche was

formed, which was occupied by migrant workers from

post-Soviet countries, including Ukraine.

In addition to economic factors, socio-political

factors also contributed to the activation of labor mi-

gration processes. Thus, 2014 was a turning point

for migration, since the military events in the east of

Ukraine, the annexation of the Autonomous Repub-

lic of Crimea caused a new wave of migration. At

the same time, the directions of flows of Ukrainian

guest workers to Russia, to the west to the EU, in

particular to Poland, have changed significantly. The

introduction of a visa-free regime in 2017 signifi-

cantly simplified and reduced the cost of finding jobs

Kalashnikova, L., Chorna, V. and Zoska, Y.

Ukrainian Guest Workers in the Labor Market of Poland: Changing Trends in Labor Migration Processes.

DOI: 10.5220/0011930500003432

In Proceedings of 10th International Conference on Monitoring, Modeling Management of Emergent Economy (M3E2 2022), pages 5-14

ISBN: 978-989-758-640-8; ISSN: 2975-9234

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

5

and study for Ukrainians abroad, which also helped

to strengthen their migration sentiments. The move-

ment of Ukrainian guest workers in the direction of

Poland until 2019 was predominantly transnational in

nature, as there was a constant movement of labor

migrants between the national spaces of Ukraine and

Poland with financial participation in the economies

of the two countries at the same time. However, the

trends have changed dramatically in connection with

the global COVID-19 epidemic and severe restric-

tions on human rights of movement.

2 RELATED WORK

The study of trends in the international movement of

Ukrainian labor force in the direction of Poland is rel-

evant from the point of view of coordinating the mi-

gration policies of both countries. That is why both

Polish (Jaroszewicz (Jaroszewicz, 2014), Iglicka and

Gmaj (Iglicka and Gmaj, 2011), etc.) and Ukrainian

scientists (Libanova and Pozniak (Libanova and Poz-

niak, 2020), Kulitskyi (Kulitskyi, 2020), Kulchytska

et al. (Kulchytska et al., 2020), Malinovska (Mali-

novska, 2015)) paid enough attention to the analysis

of recent trends in this area. Considering the numer-

ous publications covering the results of various kinds

of empirical studies, Polish colleagues studied the

problems of labor migration of Ukrainians in much

more detail. Whereas most of the Ukrainian devel-

opments relate to Poland indirectly, as the problems

of external mobility of Ukrainian guest workers were

studied only in the context of migration processes in

general.

3 RESEARCH QUESTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has made significant

changes in the situation of Ukrainian guest workers

in Poland, which is why there is an urgent need to

investigate the existing changes in labor migration

processes trends based on secondary analysis of data

of empirical sociological research conducted by the

Ukrainian Institute of the Future, the CEDOS an-

alytical agency, the Personnel Service employment

agency, the Gremi Personal analytical center of the

international employment company, and the statisti-

cal data of the International Organization for Migra-

tion, the State Migration Service of Ukraine, the State

Statistics Service of Ukraine, the Ministry of Family

and Social Development of Poland.

4 RESEARCH METHODS

The use of the secondary analysis method made it

possible to group the primary sociological informa-

tion presented in the form of linear distributions and

statistical tables in accordance with the objectives of

the study. In particular, we are talking about the pos-

sibility of comparing the results of empirical socio-

logical research with generalized statistical data pub-

lished on the official websites of state statistics bodies

in order to search for patterns, relationships between

variables, generalize data, and study the temporal and

spatial dynamics of labor migration processes. To in-

crease the reliability of the analysis of data that were

collected by different researchers using various meth-

ods of collecting social information, comparison and

triangulation methods were used, which made it pos-

sible to interpret the existing trends in the labor move-

ments of guest workers.

5 RESULTS

According to the results of 2019, among the countries

in the eastern part of Europe, Ukraine closes the four

leaders of the origin of emigrants in the region (Inter-

national Organization for Migration, 2020). Migra-

tion flows between Poland and Ukraine have always

been exceptionally active. The main prerequisites

for such trends are geographical proximity, developed

transport links, socio-cultural kinship between these

countries. An equally important factor in labor mi-

gration is the implementation of legislative initiatives

for liberalizing the Polish labor market and providing

visa privileges for foreigners.

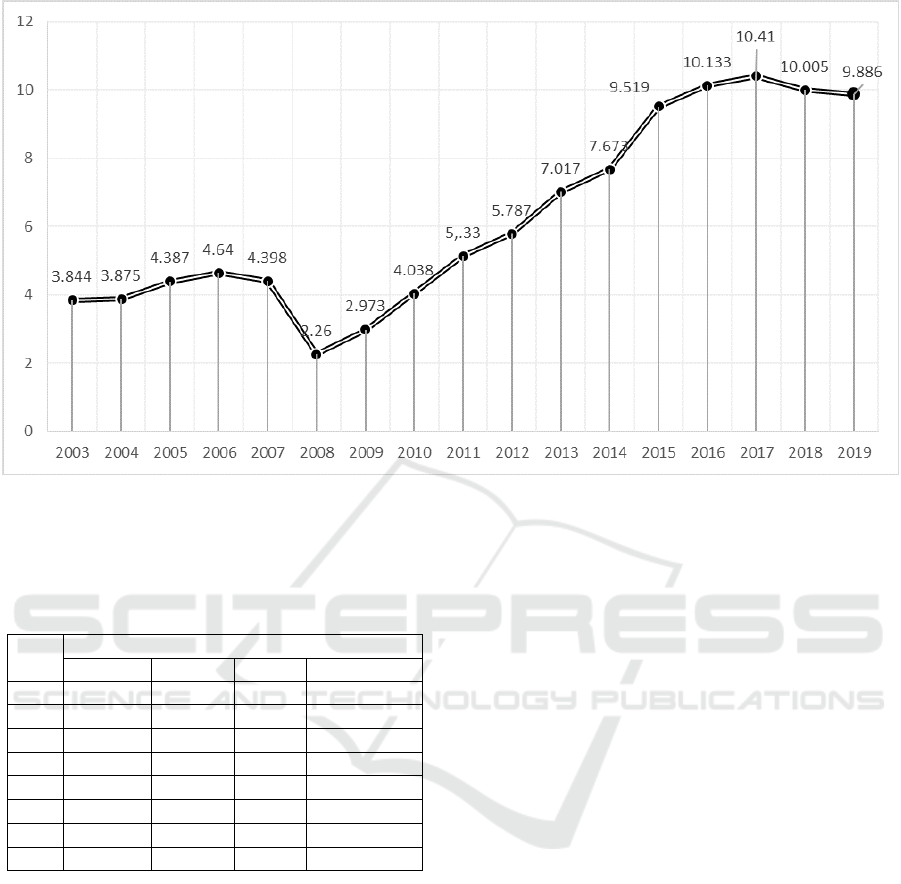

Since the introduction of the visa regime for cross-

ing the border between Ukraine and Poland in July

2003, the flow of Ukrainians intending to visit the

neighboring country has gradually increased from

3.844 million people in 2003 to 9.886 million people

in 2019, having acquired its peak in 2017 – 10.410

million people (figure 1).

The data presented capture facts about border

crossings and may refer to migrants, tourists, relatives

and friends visiting Ukrainian migrants in Poland.

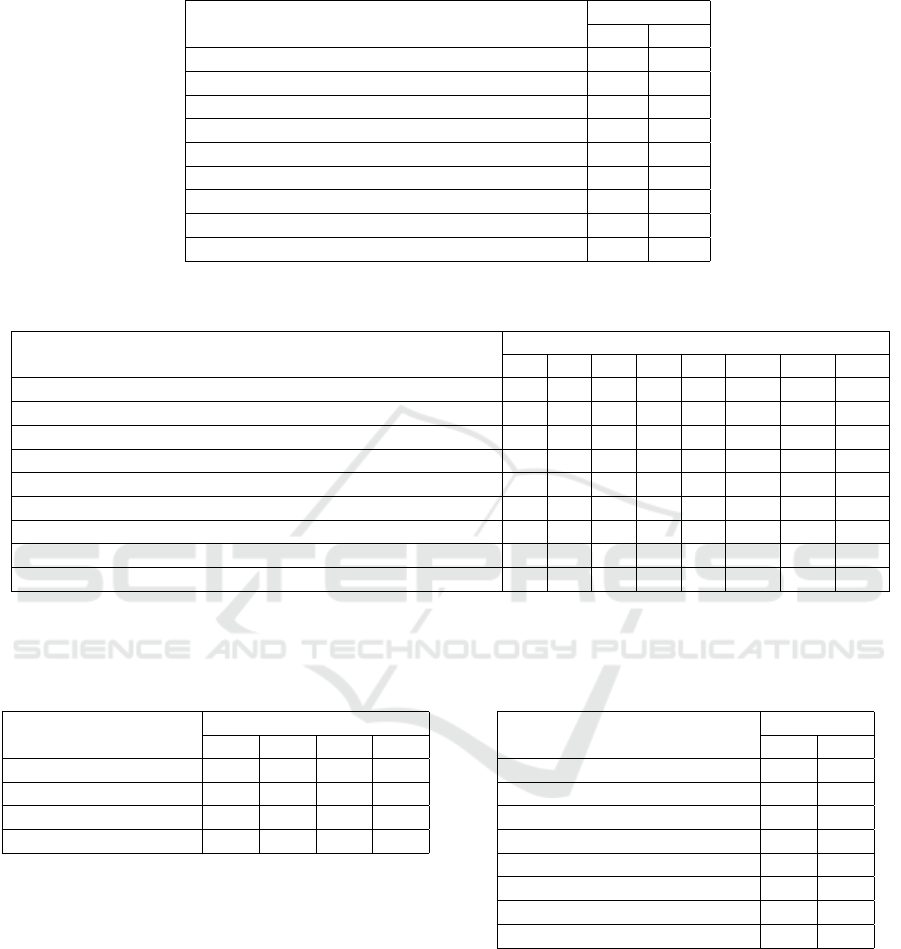

According to the data presented in table 1, in

2017 there were dramatic changes in the distribution

of migration flows associated with changes in the is-

suance – official consolidation of the right to stay for

6-9 months in Poland for foreign workers employed in

temporary and seasonal work depending on the sphere

of activity.

On the other hand, it should be noted that the na-

ture of employment has changed. In fact, according

M3E2 2022 - International Conference on Monitoring, Modeling Management of Emergent Economy

6

Figure 1: The number of Ukrainians leaving Ukraine for Poland during 2003–2019, million people (based on statistical data

(Malinovska, 2015; State Migration Service, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2020, 2019).

Table 1: Distribution of the number of Ukrainians leaving

Ukraine for Poland during 2010–2017 by the purpose of

their movement (based on statistical data (State Migration

Service, 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018).

Year

Purpose of trip

Business Tourism Private Service staff

2010 210,6 85,6 3703,4 38,6

2011 207,5 113,6 4781,8 30,4

2012 174,0 69,6 5521,6 21,9

2013 120,2 31,9 6839,6 26,4

2014 98,7 10,9 7547,4 15,7

2015 103,5 10,4 9391,9 13,5

2016 105,1 9,4 9996,6 22,1

2017 1,8 5,1 9984,1 419,3

to the information from the National Bank of Poland,

in 2017, compared to 2013, the number of Ukraini-

ans who were seasonally employed in agriculture,

forestry, hunting, fishing and other jobs, which do

not require a high level of qualification, decreased by

more than three times. The number of guest work-

ers employed in industrial production almost doubled,

and employment in households, administrative and

support services increased by 37,0%.

However, it should be noted that there were rel-

ative shifts in such spheres as industrial production,

transport, professional, scientific and technical activ-

ities, households, administrative and support services

(table 2).

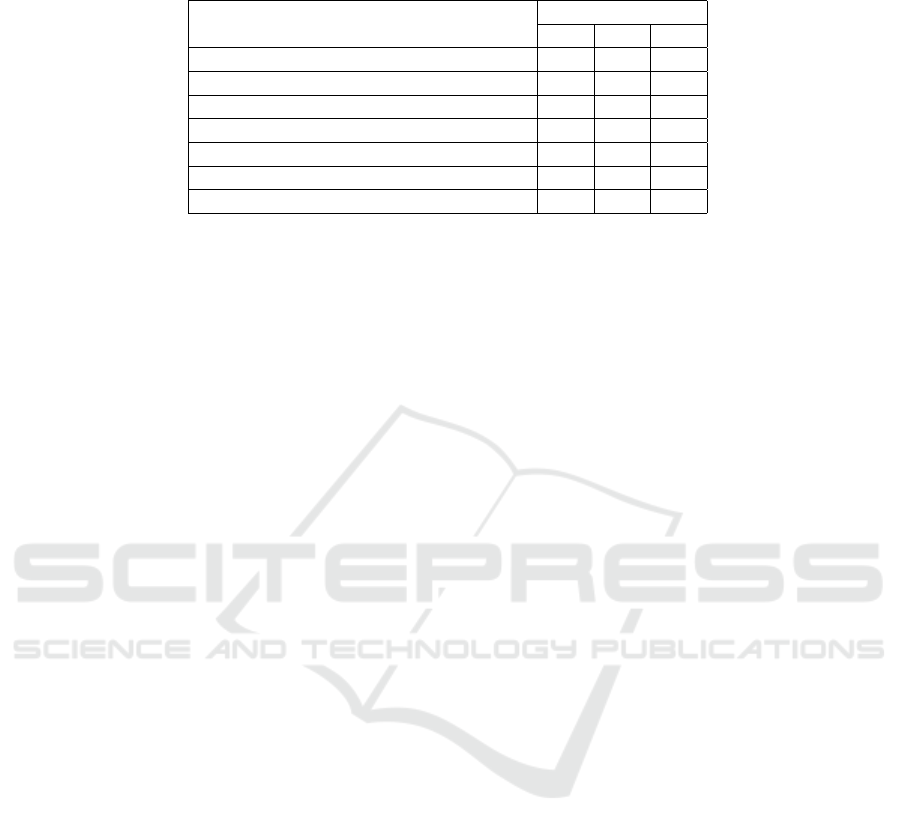

Mostly, Ukrainian guest workers in Poland were

employed in low-paid jobs, but in 2017 the number

of Ukrainians in management positions increased by

almost 2,5 times, and the number of legally employed

skilled Ukrainian workers increased as well (table 3).

The trends in the structure of the distribution of

Ukrainian emigrants by position at the place of their

employment, recorded by the data of official statis-

tics, are confirmed by the results of empirical soci-

ological research Polish Labor Market Barometer as

well. In fact, in the period 2018-2021, the number of

Ukrainian guest workers, who were working at Polish

enterprises, holding management positions, continued

to grow and increased from 7,4% in 2018 to 12,0% in

2021 (table 4).

Such shifts may be associated with the awareness

of the role of Ukrainian migrants in the Polish labor

market. Polish employers value Ukrainians for dili-

gence, adaptability, experience (table 5), the majority

(72,2%) of them believe that the level of competence

of Ukrainians is the same as that of Poles holding sim-

ilar positions (table 6).

According to the data of the Ministry of Foreign

Affairs of Poland in 2019, Polish consulates issued

more than 900 thousand visas to Ukrainians, of which

895,7 thousand were national. In 2019, the number

of work visas issued to Ukrainians for the first time

with a duration of 1 year or more in Poland was up to

44,0 thousand (compared to 28,1 thousand in 2017)

(Kulchytska et al., 2020).

The trend of short-term, pendulum or “shuttle”

migration of Ukrainian guest workers has given way

Ukrainian Guest Workers in the Labor Market of Poland: Changing Trends in Labor Migration Processes

7

Table 2: The structure of legalized employment temporary/ seasonal work of Ukrainian guest workers in the Polish labor

market by the type of work permits, % of the total number (Ukrainian Institute of the Future, 2017).

Spheres of employment

Year

2013 2017

Agriculture, forestry, hunting and fishing 53,67 17,70

Trade and car service 4,78 3,69

Industrial production 6,94 12,70

Transport 1,84 4,45

Households, administrative and support services 2,49 39,43

Professional, scientific and technical activities 0,55 1,67

Repair, construction and architecture 11,95 12,53

Catering and hotel management 1,47 2,44

Other services and works 16,31 5,41

Table 3: The number of registered Ukrainian employees by the place of work in Poland (Ministerstwo Rodziny i Polityki

Społecznej, 2018).

Place of work (profession)

Year

2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

Management positions 417 422 489 575 735 1152 2098 5093

Persons who are members of the board of legal organizations 124 126 137 150 142 130 102 675

Skilled workers 3552 6972 7830 5696 9197 22198 43523 79489

Unskilled workers 3397 4318 4665 4801 4744 13108 27337 99071

Information systems engineers, programmers 28 53 43 86 136 702 1245 1500

Artists 96 79 71 70 73 143 191 290

Junior medical staff 20 53 42 50 101 259 311 297

Doctors 10 13 6 5 6 11 119 16

Teachers 68 32 28 28 29 74 151 176

Table 4: Distribution of employers’ answers to the question

“What positions do Ukrainian citizens occupy in your com-

pany?”, % of the total number of respondents (Personnel

Service, 2017, 2020, 2021).

Positions at enterprises

Year

2018 2019 2020 2021

Low-level employees 73,4 71,9 70,0 70,0

Skilled mid-level staff 27,4 20,2 21,0 14,0

Skilled senior staff 7,3 3,9 8,7 12,0

It is difficult to answer 6,4 4,1 0,3 4,0

to long-term and sometimes permanent movement.

Most manifestations of labor mobility have become

legal, but this has not completely excluded the pres-

ence of illegal employment. Not only the terms of

stay outside Ukraine have changed, but also the di-

rections of movement. If before the events of 2014,

mostly residents of the border regions of Ukraine

went to neighboring Poland in large numbers, then

after 2014 the center of gravity of labor movements

shifted slightly to the center of the country. In

fact, those Ukrainians who were forced to leave

their homes in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea,

Luhansk and Donetsk regions, as well as residents of

other regions fled outside the national space in search

Table 5: Distribution of employers’ answers to the question

“What is primarily assessed by your company in employees

from Ukraine?”, % of the total number of selected answer

options (Personnel Service, 2020, 2021).

Virtues of Ukrainian workers

Year

2020 2021

Diligence 62,4 42,0

Rapid adaptation 47,4 32,0

Speed of learning 35,6 26,0

Knowledge 30,1 20,0

Creating a positive atmosphere 29,8 15,0

Experience 26,7 32,0

Modesty 24,0 21,0

It is difficult to answer 6,4 4,0

of a better life.

Nor should the assumption of a close two-way re-

lationship between labor and educational migration

be rejected. In some places, the existing migration

networks of Ukrainian guest workers, pursuing the

goals of reuniting parents and children, have caused

waves of educational migration. However, such ob-

jective factors as the European integration policy of

the Ukrainian state, the Bologna process, etc. have

also influenced the processes of educational migra-

M3E2 2022 - International Conference on Monitoring, Modeling Management of Emergent Economy

8

Table 6: Distribution of employers’ answers to the ques-

tion “How do you assess the competencies of workers

from Ukraine compared to Poles working in the same po-

sitions?”, % of the total number of respondents (Personnel

Service, 2019, 2020, 2021).

Level of competence

Year

2020

More competent 4,7

Just as competent 72,2

Less competent 14,2

It is difficult to answer 8,9

tion.

Thus, the number of Ukrainian students study-

ing in Polish higher education institutions in the

2010–2011 academic year was 3,570 thousand peo-

ple, while in 2016–2017 – their number increased by

10 times, reaching a total of 355,584 thousand peo-

ple (Statistics Poland, 2020). According to the study

“Ukrainian students in Poland: policies of attrac-

tion, integration and motivation and students”plans”

conducted by the analytical agency CEDOS during

March-May 2018 (N = 1055), half of the surveyed

Ukrainian educational migrants combine study with

work. After completion of their studies in Poland,

only 6,0% of Ukrainian students want to return home,

23,0% of respondents intend to stay in this country,

32,0% of students plan to work in the EU countries or

outside of it, while all others have not yet decided on

their intentions (Stadny, 2019).

Under the conditions of quarantine, the possibili-

ties of e-learning have expanded (Kalashnikova et al.,

2022; Vakaliuk et al., 2022). It can be assumed that

this is why, in the competition for applicants, which

will take place between Ukrainian and Polish higher

education institutions, and most likely, the latter will

win. Remote forms of organizing the educational pro-

cess deepen the indicated trend in educational move-

ments, which, in turn, will lead to the emergence of

new trends in labor migration processes. Namely, it

will contribute not only to a significant rejuvenation

of Ukrainian guest workers, but also to intensification

of the outflow of highly skilled labor forces.

Many years of migration experience and the ex-

isting trends in labor migration processes of recent

years have contributed to the formation of migration

networks. They, being a form of social capital in the

transnational space, significantly increase the likeli-

hood of labor force movements, taking into account

the possibility of minimizing the risks associated with

finding a job, study, residence, etc. Such networks as

an independent factor in intensification of labor mo-

bility, regardless of its root causes (mass unemploy-

ment and impoverishment of the population) became

the impetus for Ukrainians to move to work to the EU

countries in the early 1990s and remain valid to this

day. According to the estimates of the State Statistics

Service of Ukraine for the period 2015–2017, among

Ukrainian labor migrants in Poland, there were 73,0%

of those who found a job through friends, relatives,

acquaintances, 16,7% – through private individuals,

5,5% – through employers, 5,4% – through private

agencies, 8,3% – in other ways (State Statistics Ser-

vice of Ukraine, 2017).

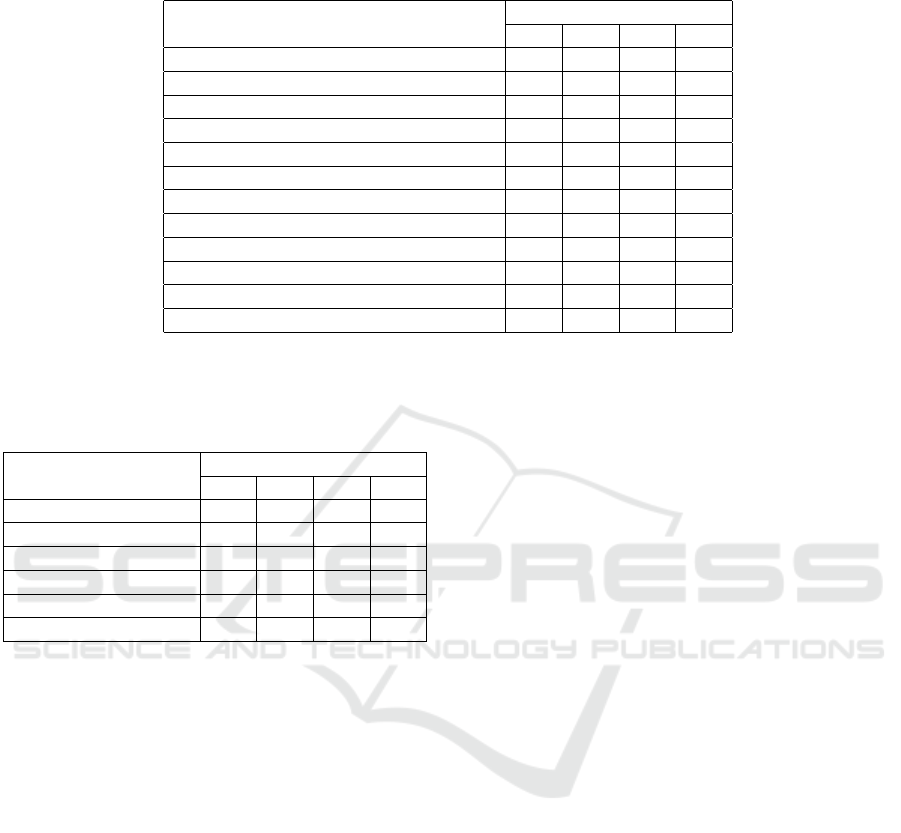

The data of the Polish Labor Market Barometer

(2017–2020) research also confirm the assumptions

about the self-continuation of migration through the

functioning of labor migration networks, as the most

effective way to find Ukrainian workers is family and

friend ties. In the second half of 2019, the number

of employers’ appeals to labor offices in Poland de-

creased sharply. Instead, searches through social net-

works and online services in Ukraine intensified. This

is confirmed by the fact that in the conditions of quar-

antine it was extremely difficult for employers to re-

turn illegal labor migrants who were forced to return

to donor-countries or decided to “sit out” the lock-

down in Poland (table 7).

The All-Ukrainian Association of International

Employment Companies reported that over the period

March-May 2019, about 5-10% of the total number

of labor migrants returned to Ukraine. Among them

there are mostly those who worked seasonally on

short-term contracts. Whereas those who had long-

term contracts as well as permanent residence permit

in the recipient-countries remained abroad, even hav-

ing lost their jobs due to the economic crisis caused

by the epidemic. Already in May 2020, after the end

of the lockdown, most of those who returned to their

homeland, went back to work (Libanova and Pozniak,

2020).

The main reason for this was that Polish em-

ployers, realizing the dependence of the success of

their business on the lack of Ukrainian labor forces,

quickly implemented a number of precautionary mea-

sures to return and retain workers (providing social

guarantees, raising wages, migration amnesty, which

provides automatic continuation of the term of work

visas for the period of the epidemic and 30 days af-

ter its completion, i.e. for two months if the quaran-

tine measures are extended). Thus, in Poland the state

program Crisis Shield was being implemented, within

the framework of which foreigners who were prop-

erly employed, but lost their source of income due

to the economic crisis, received social benefits in the

amount of about 1400–2080 zlotys (10.3–13.5 thou-

sand hryvnias) (Kulchytska et al., 2020).

According to the data of the Polish Labor Mar-

Ukrainian Guest Workers in the Labor Market of Poland: Changing Trends in Labor Migration Processes

9

Table 7: Distribution of employers’ answers to the question “How does your company look for or intend to look for employees

from Ukraine?”, % of the total number of these answer options (Personnel Service, 2019, 2020).

Ways to find Ukrainian workers

Year

2017 2019 2020

Through families or friends from Ukraine 35,0 49,0 61,5

Through agencies 48,0 35,8 45,9

Through labor offices in Poland 38,0 7,2 33,4

On online services in Ukraine 23,0 39,3 30,3

Through social media 10,0 19,8 16,0

Through labor offices in Ukraine 15,0 0,5 7,4

It is difficult to answer 0 0 0,4

ket Barometer research during 2017–2021, Polish em-

ployers have significantly expanded the areas of so-

cial support for Ukrainian labor migrants. Thus, due

to quarantine measures in 2020, significantly more

companies offered assistance to workers in arrang-

ing formalities regarding their official stay in Poland.

In 2021, the list of areas of social support included

among other things testing for COVID-19, accommo-

dation for quarantine stay after returning to Poland,

free insurance in case of COVID-19 illness (table 8).

The analysis of the data shows that if earlier

for Ukrainians economic (uneven economic develop-

ment, desire for material well-being) and social (the

possibility of self-affirmation, decent working condi-

tions) motives of international labor force movements

prevailed, today it is about a shift towards political

(escape from persecution, avoidance of discrimina-

tion) and military (conducting military operations on

the territory of the native country) motives.

Migrants are more than other groups of the popu-

lation affected by the introduction of quarantine mea-

sures. Competition in the labor market has increased

significantly due to mass unemployment caused by

the partial suspension of activities or closure of en-

terprises. According to the assessment of the ex-

perts of the Personnel Service employment agency,

one in three Polish workers employed in Germany,

Austria, Britain and other Western European coun-

tries lost his/her job and returned to Poland. Accord-

ingly, the needs of the Polish labor market for cheap

labor force of foreign workers, including Ukrainians,

have decreased significantly.

This is confirmed by the decrease in the number of

vacancies in the Polish labor market, which in 2017

had 152 thousand offers, in 2018 – 165 thousand, in

2020 – 81 thousand. The manufacturing industry suf-

fered the most, where the number of vacancies de-

creased by 9,8 thousand people, which amounted to

36,0% of the indicators of 2019, construction – by 9,5

thousand (46,0% ) and trade – 7.6 thousand (40,0%)

(Fra¸czyk, 2020).

Along with socio-economic problems, the prob-

lems of xenophobia and intolerance, partially caused

by them, became relevant. In particular, we are talk-

ing about statements by both the representatives of the

indigenous population of the recipient-countries and

compatriots who accused labor migrants of spreading

coronavirus infection.

According to the results of the Polish Labor Mar-

ket Barometer research during 2017-2021 the nature

of the attitude of employers towards emigrants from

Ukraine has changed significantly. Thus, in 2021,

compared to 2017, the number of those who have a

negative attitude towards Ukrainian guest workers has

increased by 8 times. On the other hand, the num-

ber of Poles who evaluate them positively has doubled

(table 9). Such shifts took place mainly due to the de-

lineation of their personal attitude of those employers

who in 2017 characterized their attitude as neutral.

In order to verify the hypotheses about the exist-

ing shifts in the trends of international labor move-

ments of Ukrainians in the context of a pandemic,

an attempt was made to systematize the results of an

empirical sociological study conducted by the ana-

lytical center of international employment company

Gremi Personal (Poland) in February 2020 with the

usage of technologies of computerized telephone sur-

vey system CASI among 1,100 thousand Ukrainian

guest workers who worked in Poland (Our Poland,

2021).

The first shifts in the trends of transnational labor

migration are associated with the rejuvenation of the

contingent of guest workers, as the majority of the

working population is leaving – under the age of 39.

Ukraine continues to lose its intellectual elite, since

a third of migrant respondents have higher education

(28,4%) and every second informant has a vocational

or specialized secondary education (47,8%).

The vast majority of respondents (68,3%) are to

some extent satisfied with the working conditions in

Poland. Among the main reasons for leaving their

own homeland, respondents focused on significantly

higher wages compared to Ukraine (80,6%), the sta-

ble economic situation in Poland (27,9%) and the op-

M3E2 2022 - International Conference on Monitoring, Modeling Management of Emergent Economy

10

Table 8: Distribution of employers’ answers to the question “What additional types of assistance do you offer to your employ-

ees from Ukraine?”, % of the total number of these answer options (Personnel Service, 2019, 2020, 2021).

Types of assistance

Year

2017 2019 2020 2021

Assistance in arranging formalities 37,0 49,3 67,2 35,0

Social payments 25,0 39,1 49,3 24,0

Accommodation 24,0 30,1 40,7 27,0

Transport to the workplace 19,0 18,4 25,4 22,0

Internet 12,0 10,9 16,5 15,0

Food 9,0 14,0 15,1 15,0

Accommodation for quarantine time - - - 20,0

Testing for COVID-19 - - - 16,0

Free health insurance against COVID-19 - - - 12,0

Food 9,0 14,0 15,1 15,0

We do not offer anything 24,0 15,0 10,0 8,0

It is difficult to answer 0 0 0,6 0

Table 9: Distribution of employers’ answers to the ques-

tion “What is the attitude of your company as an employer

to employees from Ukraine?”, % of the total number of re-

spondents (Personnel Service, 2019, 2020, 2021).

Attitude

Year

2017 2019 2020 2021

Mostly positive 7,0 8,6 8,8 14,0

Positive 22,0 34,1 24,0 22,0

Neutral 71,0 46,8 56,0 49,0

Negative 0 0,3 1,7 5,0

Mostly negative 0 0,8 0,7 3,0

It is difficult to answer 0 9,4 8,8 7,0

portunity to get a work visa or temporary residence

permit, which is relatively easier than in other EU

countries (25,4%). Guest workers consider the lack

of jobs in Ukraine (70,9%), the poor economic situa-

tion (49,0%), the lack of prospects, opportunities for

self-realization (23,2%), political instability (22,8%),

and corruption (14,0%) to be the inhibitory factors for

returning home. At the same time, curiously enough,

the least of all informants are worried about the mili-

tary conflict in the east of the country (7,2%), loss of

business (4,1%), crime (1,2%) or poor quality medi-

cal care (3,1%).

One in five respondents (18,6%) is dissatisfied

with the attitude of Poles towards them at work, es-

pecially noting the growing trends of discrimination

in the context of a pandemic.

Speaking about integration intentions, it should

be noted that half of the respondents (46,4%) ex-

pressed a desire to stay and live in Poland. More

than a third of respondents (35,1%) do not consider

the possibility of returning to Ukraine at all. A di-

rect confirmation of these trends is the intention of

the majority of guest workers (66,5% in 2021, com-

pared to 60,0% in 2020) to obtain a permanent res-

idence permit in Poland. In addition, 51,7% (com-

pared to 41,0% in 2020) of Ukrainians plan to move

their families to Poland. Also significant is the de-

sire of Ukrainian migrant workers to open their own

business in Poland – in 2020, 25,0% respondents had

such intentions, while in 2021 there were significantly

more applicants (39,8%). The number of migrants

considering the possibility of buying their own hous-

ing and other real estate in Poland has doubled, from

34,0% in 2020 to 55,5% in 2021.

A noticeable increase in all these indicators tes-

tifies an increase in the integration sentiments of

Ukrainians, a significant expansion of transnational

spaces. More than half of the informants (54,1%) ex-

pressed their intention to continue moving to other EU

countries in search of work in the event of a worsening

situation in Poland due to the pandemic. This trend,

even taking into account the pandemic and lockdown,

has not changed compared to the results of similar

studies conducted in 2020. Among the most accept-

able areas of possible labor mobility, Ukrainians con-

sider Germany, Scandinavian countries, the Czech

Republic, Canada and the United States. In particu-

lar, interest in the Scandinavian countries has almost

doubled (42,5% of respondents in 2021 compared to

22,0% in 2020).

In the study “Foreign worker in the era of a pan-

demic”, conducted by EWL SA, the Foundation for

the Support of Migrants in the Labor Market “EWL”

and the Center for Eastern European Studies at the

University of Warsaw in the period April-May 2021

took part labor migrants who were in Poland during

the pandemic (N = 620 people, including 92,4% from

Ukraine, 4,2% from Belarus, 2,3% from Moldova and

1,1% from other countries) (table 10).

Ukrainian Guest Workers in the Labor Market of Poland: Changing Trends in Labor Migration Processes

11

Table 10: Distribution of employers’ answers to the question “What arguments prompted you to stay in Poland during the

epidemic?” (respondents who were working in Poland at the time of the outbreak of the pandemic) (Zymnin et al., 2021).

Answer options

Year

2021

I worked in Poland before the outbreak of the pandemic and did not want to change my plans 50,0

I would like to continue employment in Poland as long as there is such a possibility 36,7

My permits for legal residence and work have been automatically extended 24,3

There is a job shortage in my country during a pandemic 23,0

During the pandemic I feel safer in Poland than in my country 12,8

No I will be able to come to Poland for a longer time 7,1

The health service in Poland functions better than in my country 6,2

The health service in Poland functions better than in my country 6,2

After returning to my home country I will be forced / forced to go to quarantine 4,9

My employer convinced me to stay 4,9

Other 4,4

The data obtained indicate that 27,0% of respon-

dents declare that due to the pandemic they had to

find a new job in Poland. 79,0% migrants will rec-

ommend work in Poland to their friends and rela-

tives. 91,0% foreigners do not regret that remained in

Poland during the pandemic. 55,0% respondents have

used or are planning to take advantage of the auto-

matic renewal of permits to stay and work in Poland.

For 36,0% of foreigners, the biggest difficulty dur-

ing work in Poland during a pandemic is separation

from their families. This is most likely related to this.

the reason, and also due to the introduction of rules

aimed at avoiding the quarantine, more and more for-

eigners decide to travel despite the ongoing epidemic.

In September 2020, every fifth respondent left Poland

during the pandemic. In May 2021, this figure was al-

ready 37,0% of the respondents. 51,0% of foreigners

are interested in working in Germany, Poland ranks

in second place – 48,0% of respondents want to work

with us. Are also rated high in the ranking Czech Re-

public (26,0%), USA (25,0%), Canada (23,0%) and

Norway (21,0%) (Zymnin et al., 2021).

6 CONCLUSION

The change in the trends of transnational labor migra-

tion of Ukrainians by the beginning of 2019 provided

a shift in the center of gravity towards the EU, in par-

ticular Poland, strengthening the relationship between

such types of movement as educational and labor mi-

gration, and a significant rejuvenation of guest work-

ers. The desire for temporary, pendulum labor mobil-

ity gave way to the desire to leave Ukraine forever and

settle abroad with the whole family. After 2019, in

the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the situation

only worsened, because no more than 5-10% of the

total number of guest workers returned home. This, in

its turn, indicates a qualitative change in the motiva-

tion of labor movements, even despite the temporary

increase in xenophobia and intolerance.

Quarantine measures are unlikely to significantly

change the intentions of Ukrainians to leave Ukraine

for Poland. In fact, despite the existing panic among

Ukrainian guest workers, which was provoked by the

first lockdown in the spring of 2019, the number of

those who returned home did not exceed 5-10%. And

after the relative stabilization of the situation in the

EU, in particular in Poland, the majority of migrant

workers went abroad to work again. This is evidenced

by the steady increase in the number of Ukrainian

guest workers in Poland in the second half of 2020.

In contrast to the state bodies of Poland, the

Ukrainian authorities are showing outright inactivity

towards the regulation of labor migration processes.

Ukraine still does not even have an effective mech-

anism for recording international illegal labor move-

ments, not to mention projects to regulate labor flows

at the level of state migration policy. Despite sig-

nificant losses of human capital and deepening de-

mographic crisis, the Ukrainian government has re-

lied on increasing revenues to the country’s budget,

considering labor movements as a direction of invest-

ment in the Ukrainian economy and a way to reduce

unemployment, maintenance and social security of

low-income citizens. This is eloquently evidenced

by statistics – according to the data of the National

Bank of Ukraine, the volume of private remittances

in 2020 reached a record 12.1 billion dollars, which

is about 10,0% of Gross Domestic Product of the

country (National Bank of Ukraine, 2021). Until the

Ukrainian economy generates enough jobs, provides

decent working conditions and high wages, taking

into account the available human capital, Ukrainian

M3E2 2022 - International Conference on Monitoring, Modeling Management of Emergent Economy

12

employers will increasingly suffer from a lack of

skilled workers, losing the struggle for labor re-

sources in the global labor market, and Ukraine will

remain the main supplier of highly skilled workers for

the EU countries, including Poland.

The war in Ukraine actualizes a new round of la-

bor migration processes. New trends will be associ-

ated, firstly, with the return of male labor migrants

from the EU countries, the USA, Canada and other

countries to Ukraine, and secondly, with the activa-

tion of both internal and external forced displace-

ments of the labor force.

Active hostilities in Ukraine in 2022 caused a new

wave of migration to Poland, which is characterized

by the movement of mainly women with children for

an indefinite period of time. As a result of the move-

ment of such a specific socio-demographic group, the

demand for educational, medical and social services

has increased, and the number of workers employed

in these areas has increased. A new migration trend

may be associated with the movement to Poland of

Ukrainian men who come after the end of the war to

reunite with their families, who were moved there ear-

lier since the beginning of hostilities in Ukraine. The

new tendencies of labor migration, caused by the war,

require their detailed study, in particular with the help

of sociological tools.

REFERENCES

Fra¸czyk, J. (2020). Znalezienie nowej pracy znowu robi sie¸

trudne. Koniec rynku pracownika nie tylko w Polsce.

Business insider. https://tinyurl.com/36pv5r6c.

Iglicka, K. and Gmaj, K. (2011). The METOIKOS Re-

search Project. Circular migration patterns in South-

ern and Central Eastern Europe: Challenges and op-

portunities for migrants and policy makers. Technical

report, Fiesole, Italy. https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/

1814/19720.

International Organization for Migration (2020). World

Migration Report 2020. https://publications.iom.int/

system/files/pdf/final-wmr 2020-ru.pdf.

Jaroszewicz, M. (2014). Ukrainians’ EU migration

prospects. OSW | Commentary, (128). https:

//www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/osw-commentary/

2014-02-25/ukrainians-eu-migration-prospects.

Kalashnikova, L., Hrabovets, I., Chernous, L., Chorna, V.,

and Kiv, A. (2022). Gamification as a trend in or-

ganizing professional education of sociologists in the

context of distance learning: analysis of practices.

Educational Technology Quarterly, 2022(2):115–128.

https://doi.org/10.55056/etq.2.

Kulchytska, K., Kravchuk, P., and Sushko, I. (2020). Trans-

formations of labor migration from Ukraine to the

EU during the COVID-19 pandemic. Representation

of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation in Ukraine, Kyiv,

Ukraine. http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/ukraine/

17320.pdf.

Kulitskyi, S. (2020). Ukrainian labor force in the

Polish labor market at the present stage of eco-

nomic development. Public opinion on lawmaking,

(18–19 (203–204)). http://nbuviap.gov.ua/images/

dumka/2020/18-19.pdf.

Libanova, E. M. and Pozniak, O. V. (2020). External la-

bor migration from Ukraine: the impact of COVID-

19. Demography and social economy, (4 (42)). https:

//doi.org/10.15407/dse2020.04.025.

Malinovska, O. A. (2015). Ukrainian-Polish Migration Cor-

ridor: Features and Importance. Demography and

social economy, (2 (24)). https://doi.org/10.15407/

dse2015.02.031.

Ministerstwo Rodziny i Polityki Społecznej (2018).

Cudzoziemcy pracuja¸cy w Polsce - statystyki.

https://archiwum.mrips.gov.pl/analizy-i-raporty/

cudzoziemcy-pracujacy-w-polsce-statystyki/.

Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych (2014). Polskie 10 lat

w Unii: Raport. https://issuu.com/msz.gov.pl/docs/

10lat plwue/.

National Bank of Ukraine (2021). The volume of remit-

tances within Ukraine in 2020 increased by almost a

quarter. https://tinyurl.com/yx76wnky.

Our Poland (2021). Sociological survey: Most Ukrainians

do not plan to return from Poland to Ukraine. https:

//tinyurl.com/2pwffwsa.

Personnel Service (2017). Barometr imigracji zarobkowej:

II p

´

ołrocze 2017. Ukrai

´

nski pracownik w Polsce.

https://personnelservice.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/

07/BarometrImigracjiZarobkowej PersonnelService.

pdf.

Personnel Service (2019). Barometr imigracji zarobkowej:

II p

´

ołrocze 2019. Ukrai

´

nski pracownik w Polsce.

https://personnelservice.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/

07/BarometrImigracjiZarobkowej IIH2019.pdf.

Personnel Service (2020). Barometr Polskiego Rynku

Pracy. http://personnelservice.pl/wp-content/uploads/

2020/07/Barometrrp2020.pdf.

Personnel Service (2021). Barometr

Polskiego Rynku Pracy. https://

personnelservice.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/

Barometr-Polskiego-Rynku-Pracy-2021.pdf.

Stadny, Y. (2019). Ukrainian Students Abroad: Data for

the Academic Year of 2017/18. https://tinyurl.com/

ye579nrr.

State Migration Service (2014). Migration profile 2010-

2013: Report. https://dmsu.gov.ua/assets/files/mig

profil/ukr migration profile 2015 1.pdf.

State Migration Service (2016). Migration profile 2011-

2015: Report. https://dmsu.gov.ua/assets/files/mig

profil/mp2015.pdf.

State Migration Service (2017). Migration profile for

2016: Report. https://dmsu.gov.ua/assets/files/mig

profil/mig prifil 2016.pdf.

State Migration Service (2018). Migration profile for

2017: Report. https://dmsu.gov.ua/assets/files/mig

profil/migprofil 2017.pdf.

Ukrainian Guest Workers in the Labor Market of Poland: Changing Trends in Labor Migration Processes

13

State Migration Service (2019). Migration profile for

2018: Report. https://dmsu.gov.ua/assets/files/mig

profil/migprofil 2018.pdf.

State Migration Service (2020). Migration profile for

2019: Report. https://dmsu.gov.ua/assets/files/mig

profil/migprofil 2019.pdf.

State Statistics Service of Ukraine (2017). External la-

bor migration of the population (according to the re-

sults of the modular sample survey): statistical bul-

letin. https://ukrstat.gov.ua/druk/publicat/Arhiv u/11/

Arch ztm.htm.

Statistics Poland (2020). Rocznik Statystyczny

RP 2003–2017. https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/

statistical-yearbooks/statistical-yearbooks/

statistical-yearbook-of-the-republic-of-poland-2017,

2,17.html.

Ukrainian Institute of the Future (2017). How Poland

fights for Ukrainian labor migrants. Ukrainian insti-

tute of the future: press release. https://tinyurl.com/

mwt9pujk.

Vakaliuk, T., Spirin, O., Korotun, O., Antoniuk, D.,

Medvedieva, M., and Novitska, I. (2022). The cur-

rent level of competence of schoolteachers on how

to use cloud technologies in the educational process

during covid-19. Educational Technology Quarterly,

2022(3):232–250. https://doi.org/10.55056/etq.32.

Zymnin, A., Kowalski, M., Karasi

´

nska, A., Lytvynenko, O.,

Stelmach, F., Da¸browska, E., Bryzek, S., and Bon-

daruk, O. (2021). Raport z III edycji badania socjo-

logicznego “Pracownik zagraniczny w dobie pan-

demii”, przeprowadzonego przez EWL S.A., Fundacje¸

Na Rzecz Wspierania Migrant

´

ow Na Rynku Pracy

“EWL” i Studium Europy Wschodniej Uniwersytetu

Warszawskiego. EWL S.A., Warszawa, Polska Repub-

lic. https://pl.naszwybir.pl/wp-content/uploads/sites/

2/2021/06/raport 2021 covid pol media light.pdf.

M3E2 2022 - International Conference on Monitoring, Modeling Management of Emergent Economy

14