The Impact of Motivation on Collaborative Consumption Through

Behavioral Intention in Taiwan

Endyastuti Pravitasari¹ and Shui-Shun Lin²

¹Universitas 17 Agustus 1945 Jakarta, 14350, Indonesia

²National Chin-Yi University of Technology, Taichung, 41170, Taiwan

Keywords: Collaborative Consumption, Consumer’s Behavior, Motivation.

Abstract: Collaborative consumption has emerged as a phenomenon widely described by academic literature to promote

more sustainable consumption practices such as sharing over ownership, peer-to-peer lending, and renting.

The aim of this study is to analyze the motivational factors of collaborative consumption in the era of the

sharing economy, as a part of planned behavior with attitude as a moderating variable of Taiwan customers.

The hypothesis tested with a simple random sampling technic with the total number of 203 Taiwanese. The

finding indicates that Taiwan customers really pay attention to the impact of sustainability in the way they

examine collaborative consumption products. A gap between attitude and behavioral intention also appeared

in this research.

1 INTRODUCTION

The development of information and communication

technology changes human behavior in all fields.

Openness makes boundaries between countries in the

digital age subtler. Changes are also reflected in the

consumption patterns of people around the world.

The emergence of online-based services is

penetrating rapidly and forming new opportunities for

entrepreneurs to work together with digital platforms

to market their products. From the consumer's point

of view, this collaboration is also very interesting and

beneficial when viewed in terms of effectiveness and

efficiency.

Collaborative consumption is a form of

consumption developed on the premise of peer-to-

peer exchange to provide lending, trading, renting,

gifting, bartering, swapping, and sharing of services

and goods without owning the product (Botsman &

Rogers, 2010). Instead of paying the full amount to

own a product that is later unused, people can share

ownership of a product, both goods and services by

paying a small amount of money. This not only saves

costs for consumers but also helps the economy and

the environment.

An alternative product for consumers,

collaborative consumption, also known as the sharing

economy, is a peer-to-peer business model that

involves actions to gain, donate, or share access to

products and services. These actions are organized

through community-based online platforms. Sharing,

which may become commonplace between friends

and family, is expanded to the surrounding

community. In recent years, disruptive new business

model developed by entrepreneurs to reach the

community and popularized as collaborative

consumption (CC). This model is based on the very

foundation of resource sharing and allows people to

access a resource without having to own them within

a short period (Gansky, 2010).

Existing companies can use collaborative

networks to provide products in the form of goods or

services to consumers. At the same time, companies

must provide peer-to-peer sharing for consumers to

used. According to Matzler, Veider, & Kathan

(2015), traditionally, consumers will consider about

to own a product when they wish to use it. In addition,

currently the number of consumers, who are willing

to pay to enjoy temporarily access the product is

increasing, compared to buying or owning it.

The development of an online platform that

promotes user-generated content, sharing, and

collaboration has also developed the information and

technology of web 2.0 (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010).

Common examples of this involve peer-to-peer file

sharing, collaborative online encyclopedias such

Wikipedia, open-source software repositories such as

Pravitasari, E. and Lin, S.

The Impact of Motivation on Collaborative Consumption Through Behavioral Intention in Taiwan.

DOI: 10.5220/0011976200003582

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Seminar and Call for Paper (ISCP) UTA â

˘

A

´

Z45 Jakarta (ISCP UTA’45 Jakarta 2022), pages 71-82

ISBN: 978-989-758-654-5; ISSN: 2828-853X

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

71

Github, and other content-sharing websites like

Youtube (e.g., The Pirate Bay). Recent examples

include peer-to-peer financings like microloans (like

those offered by Kiva) and crowdfunding services

(e.g., Kickstarter). The sharing economy, which we

refer to as a phenomenon, is exemplified by these four

examples: open-source software, online

collaboration, file sharing, and peer-to-peer lending.

Thus, the sharing economy situation is the result of a

series of technology advancements that have made it

easier to share both tangible and intangible goods and

services online due to the accessibility of many

informational platforms. Information technology is

the fundamental lens through which to examine the

"sharing economy".

Open-source, online collaboration, file sharing,

and peer-to-peer funding are some examples of the

sharing economy that, despite their outward

differences, have a number of things in common. To

start, they are all products of Silicon Valley's tech-

driven culture and have grown out of it. This is simply

attributable to open source software and file-sharing

websites. Sacks (2011) asserts that Silicon Valley's

tech-driven culture is also in which the first, biggest,

and most prosperous CC services have developed in

recent years. More significantly, as will be addressed

in the section on the elements of the sharing economy,

the numerous examples of the sharing economy also

share the traits of online cooperation, online sharing,

social commerce, and some type of underlying

ideology, such as collective purpose or common

good. You can also attribute CC services with all of

these qualities.

According to earlier research (Bray, Johns, &

Kilburn, 2011; Eckhardt, Belk, & Devinney, 2010),

people are deterred from ethical consumption by

institutional and financial factors. However, as new

forms of consumption through the sharing economy

have emerged, such as collaborative consumption

(CC), these problems are being addressed and may

one day be resolved. A developing economic and

technological phenomenon known as the sharing

economy is propelled by advances in information and

communications technology (ICT), rising consumer

awareness, the growth of collaborative web

communities, and social commerce and sharing

(Botsman & Rogers, 2010; Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010;

Wang & Zhang, 2012). We perceive the sharing

economy as a comprehensive term that includes

various ICT advancements and technologies, like CC,

which encourages sharing consumption.

The development and consumption of locally and

communally based products has been observed as a

result of increased public awareness of life

sustainability (Albinsson & Perera, 2012; Belk, 2010;

Botsman & Rogers, 2010; Hamari, Sjöklint, &

Ukkonen, 2016).

2 LITERATUR REVIEW

Collaborative consumption (CC) allows consumers to

fully utilize excess or idle resources, and to access

resources without necessarily purchasing or owning

them. There are several issues about CC in Taiwan.

2.1 Collaborative Consumption in

Taiwan

Taipei government imposes a ban on Uber to operate.

Thus, Uber’s refusal in Taipei by the local

Government and taxi drivers is based on a “cultural

misunderstanding” so it is seen that Uber is an illegal

transport service company (Fulco et al., 2016).

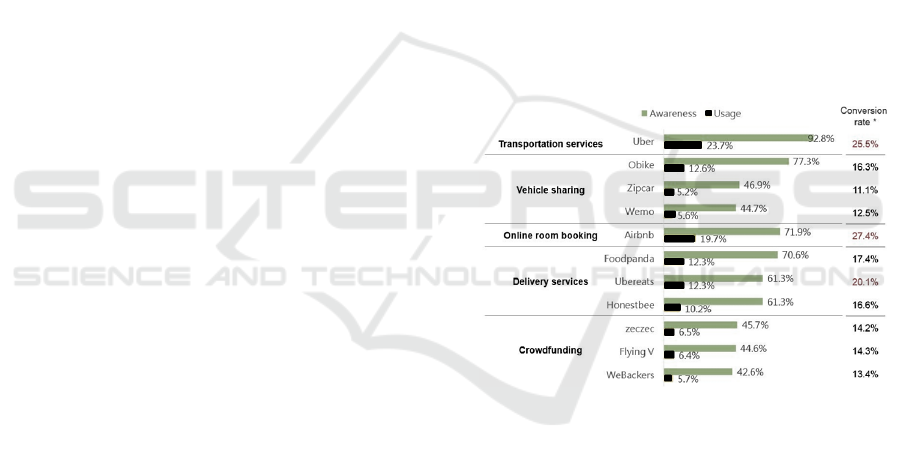

Table 1: 1 Sharing Economy in Taiwan.

*Conversion rate = usage rate/knowledge rate

Source: InsightXplorer (2018)

However, data collected by the 1935 multiple

selection questions. In total 85% heard about the

sharing economy and 55.3% know about it. In Taiwan,

four popular products for the sharing economy are

related with transportation, services, goods, and space

(InsightXplorer, 2018). Transportation services in

particular Uber have a high conversion rate from

awareness and usage numbers. From the table below,

the items of interest to users based in industries are

transportation for 54.6%, services for 46.5%, goods

for 42.4%, and space for 30.4% in total 1935

respondents.

ISCP UTA’45 Jakarta 2022 - International Seminar and Call for Paper Universitas 17 Agustus 1945 Jakarta

72

Table 2: 2 Item of interest to users (n=1935).

Produc

t

Percenta

g

e

Transportation 54.6%

Services 46.5%

Goods 42.4%

Space 30.4%

Source: InsightXplorer (2018)

2.2 Motivation as Driving Factors of

Collaborative Consumption

Interactions in economic sharing may operate in

social norms (communal relationships when both

parties weigh benefits and risks. According to Aruan

and Felicia (2019), social norms are concerned with

motivation for the desire to participate. Uysal and

Jurowski (1994) defined motivation as

psychological/biological needs and desires

considered as key factors that make people behave

concerning their activities. It was found that there is a

close relationship between tourism, human beings,

and human nature. Therefore, there is a need to

conduct an insightful investigation to know the reason

why people prefer to travel, and what they would like

to enjoy. The concept of motivation is studied in

different fields of research to interpret its phenomena

and characteristics. The features of motivation as the

primary forces behind collaborative consumption—

safety, social acceptance, stimulation, ethics, quality,

value for money, comfort, and sustainability—are

examined in more detail in the section that follows.

1. Safety

Safety concerns are related to seeking harmony

and stability (Bardi & Schwartz, 2003), realizing

life’s limitations, being conventional, and being

private (Chulef, Read & Walsh, 2001), as well as

avoidance of risks and dangers. In a consumption

setting, this may entail attention to information

regarding health issues, side-effects of

consumption, potential risks, warranties, and

insurances, as well as preferences for products

that have been well-tested and shown to conform

safety standards. Safety is important in many

consumer settings (Becker, 1973; Rindfleisch &

Burroughs, 2004). The Safety dimension was

shown related to insurances, safety, and unrest.

Define sharing commerce, while information

quality and transaction safety are chosen to

capture the technical attribute of the sharing

commerce system itself (Kong et al., 2019).

Maintaining a secure transaction system online is

more difficult than offline, users required a high

level of transaction safety and privacy which

associated with the transaction. The motivational

goals from safety are to improve or secure one’s

future well-being, feeling calm and safe

(Barbopoulos & Johansson, 2017).

2. Social acceptance

The former entails making a good impression,

fitting in, and conforming to expectations,

whereas the latter entails a focus on moral

principles and avoiding immoral or wrong

(Barbopoulos & Johansson, 2017). Social

Acceptance was shown to be related to consumer

susceptibility to interpersonal influences, for

example, asking friends for recommendations and

choosing better online services. For social

acceptance, the normative dimension in the

consumer susceptibility to interpersonal

influences (CSII) scale as reported by Bearden,

Netemeyer, & Teel (1989) was chosen as

reference. This dimension contains items

regarding social belonging and conformity to

social norms, which makes it similar to the social

acceptance dimension, with items regarding the

expectations of friends and similar others, as well

as gaining a sense of belonging.

3. Stimulation

Based on Keiler (1959), stimulation related to

triggered initial effort or measuring an existing

action. It also means to get something exciting,

stimulating, or unique, avoiding dullness

(Barbopoulos & Johansson, 2017). Consumers

motivated by the former seek to increase their

well-being, utilizing stimulation and excitement,

whereas consumers motivated by the latter seek to

increase their well-being by employing

convenience, comfort, and avoidance of effort.

4. Ethics

The Ethics dimension was related to the

universalism value type (Schwartz, 1992). It is

also related to the search for information

regarding environmental impacts and pro-

environmental travel alternatives. Based on

Barbopoulos & Johansson (2017), the motives of

ethics are to act according to moral, principles,

obligations, and avoiding guilt. The Ethics

dimension is similar to its focus on moral

righteousness.

5. Quality

The quality dimension represents the utility

derived from the perceived quality and expected

performances of the product (Sweeney & Soutar,

2001) which corresponding well with the quality

dimension. It also concerned to attaining goods of

high quality and reliability.

The Impact of Motivation on Collaborative Consumption Through Behavioral Intention in Taiwan

73

6. Value for money

The consumer perceived value (PERVAL)

dimensions which price and quality (Sweeney &

Soutar, 2001) were chosen as reference scales for

the value for money and quality dimensions. The

price dimension represents "the utility derived

from the product due to the reduction of its

perceived short term and long term costs" which

is similar to our value for money dimension, with

focus on paying a reasonable price and avoiding

wasting money.

7. Comfort

Comfort dimensions get something pleasant and

comfortable, avoid hassle and discomfort

(Barbopoulos & Johansson, 2017). Customers are

initially thrilled and eager to increase their well-

being, and after sensing that their well-being will

alter through ease, comfort, and the avoidance of

effort, they are becoming more motivated. Having

a high level of comfort within a product not only

give a sense of trust to the provider, but can also

reduce anxiety and increase consumer self-esteem

(Gaur & Xu, 2009).

8. Sustainability

Participation in CC is typically anticipated to be

extremely environmentally sustainable (Prothero

et al., 2011; Sacks, 2011). Such motives are

typically connected to ideology and norms

(Lindenberg, 2001), which are viewed as intrinsic

motivations in our theoretical framework and in

similar work (Lakhani & Wolf, 2005; Nov,

Naaman, & Ye, 2010). According to recent

advances, CC platforms are being used to promote

a sustainable market that "optimizes the

environmental, social, and economic

repercussions of consumption in order to meet the

requirements of both current and future

generations" (Phipps et al., 2013; Luchs et al.,

2011). Additionally, Nov (2007) as well as Oreg

and Nov claim that the creation of open-source

software and involvement in peer production

(such as Wikipedia) are motivated by altruistic

principles like transparency and freedom of

knowledge (2008).

Thus, participation and collaboration in digital

platforms may be influenced by attitudes sculpted by

ideology and socioeconomic concerns, such as anti-

establishment feelings or a preference for greener

consuming, which humans believe to be a notably

crucial factor in the setting of CC (Hennig-Thurau,

Henning, & Sattler, 2007). The innate drive to uphold

standards is therefore operationalized as ecological

sustainability (Hu et al, 2019).

2.3 Attitude

Attitude to be a key influence on behavior is attitude

(Ajzen, 1991). It reflects the user's evaluation of the

technology (Pietro & Pantano, 2012) Additionally,

there is cause to believe that attitudes and conduct

may differ when examining a phenomenon. It is

imperative to measure them independently. Although

customers may have strong moral and intellectual

convictions, their intentions may not always translate

into sustainable behavior (Bray, Kilburn, & Johns,

2011; Phipps et al., 2013; Vermeir & Verbeke, 2006).

A few issues might explain this attitude-behavior

gap: (a) pursuing sustainable behavior can be costly

both in terms of coordination and direct cost, (b)

people lack the means of deriving benefits from

signaling such behavior and thus not able to gain

recognition from the behavior. For instance, studies

show that people are motivated to take on sustainable

behavior especially when other consumers have been

able to signal that they are also participating

(Goldstein, Cialdini, & Griskevicius, 2008). (c) There

is not enough information for consumers about

sustainable consumption. They may enable to get

more efficient coordination for sharing activities,

which in turn aids in the facilitation of active

communities around a cause.

However, it is still unclear whether or not people's

attitudes toward CC are influenced by, for instance,

green values, and if so, whether or not they also

represent their actual conduct. Or does this situation

also reflect the attitude-behavior gap? We look into

the connection between attitudes and behaviors in

order to address this problem as well as other

predictions.

2.4 Behavioral Intention

Behavioral intention represents the degree to which

the user is willing to perform a certain behavior

(Pietro & Pantano, 2012). According to Marzuki,

Hashemi, and Kiumarsi (2017), behavioral intention

can be simply defined as a person's willingness to

work hard and level of resolve in order to carry out an

action. Behavioral intention (BI) refers to “a person’s

subjective probability that he will perform some

behavior” (Hill, Fishbein, & Ajzen, 1977).

3 METHODS

A deductive method with qualitative tools was used

in this research.

1. Pretesting survey

ISCP UTA’45 Jakarta 2022 - International Seminar and Call for Paper Universitas 17 Agustus 1945 Jakarta

74

A pretesting survey was used to test the

understandability and appropriateness of the

questions planned to be included in a regular

survey (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016) using 30

respondents.

2. Descriptive analysis

A descriptive study for a single variable is to

obtain data that describes the topic of interest

provided by frequencies, measures of central

tendency, and dispersion (Sekaran & Bougie,

2016). Demographic data, for example, gender,

age, occupation, and marital status were used in

this research. The use of mean also important to

measures the central tendency. For the measures

of dispersion of interval scale, standard deviation,

and variance used in this research.

3. Outer Model Assessment

a. Construct Validity

Validity deals with the soundness of accuracy

of a measure or the extent to which a score

truthfully represents a concept (Janadari,

Ramalu, & Wei, 2018). Convergent validity is

the extent to which a measure correlates

positively with an alternative measure of the

same construct based on the average variance

extracted (AVE) and item loadings.

Discriminant Validity relates to the

uniqueness of a construct, whether the

phenomenon captured by a construct and not

represented by other constructs in the model

(Hair et al., 2013; Janadari, Ramalu, & Wei,

2018). It can be evaluated by assessing the

cross-loadings among constructs, by using the

Fornel-Larcker criterion and Heterotrait-

Monotrait Ratio of correlation (HTMT).

b. Composite reliability

Composite reliability concerns with individual

reliability that referring to different outer-

loadings of the indicator variables (Hair et al.,

2017).

4. Structural Model (Inner Model) Assessment

The structural model is used to illustrate one or

more dependence relationships liking the

hypothesized model’s construct. Model

assessment by Hair et al., (2014) are assessed

structural model for collinearity issue, the path

coefficient, the level of R2, and the predictive

relevance (Q2).

a. R2

R-square is used to assess the predictive power

of a particular model or construct and the

determination of the standard path coefficient

of each relationship between exogenous and

endogenous variables.

b. Path coefficient

The bootstrapping technique is used for

examining the significance of all the path

coefficients (Chin, 2010). In order to assess

the direct effects of all associations that have

been postulated and statistically tested,

bootstrapping technique is performed. The

path coefficients are estimated using t-

statistics using the same methodology.

c. The predictive relevance (Q2)

The Q2 of the model which was conducted to

assess the predictive capacity of the model

through the Stone-Geisser's non-parametric

test (Blindfolding).

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Majority of respondents whom 57.6% were young

adult in the age group less than 24 years old, 27.6%

in the age group of 25 until 39 years old, and 14.8%

respondents for 40 until 55 years old. From these data

we can say that young people make up the largest

percentage of respondents and will continue to

decline according to age criteria. This is in

accordance with the opinion of Lawson (2010) which

states that millennials have a strong desire to

participate in collaborative consumption. This

outcome is anticipated given how well-versed they

are in technology.

From the category of education, majority of

Taiwan respondents, 56.7% were

diploma/undergraduate students, 31.5% respondents

were graduate/post graduate students, and 11.8% of

the respondents were school students. In line with

their status, most of respondents were single.

Furthermore, over half (61%) of those who responded

from Taiwan were students, 35% of respondents were

private employees, 3% of respondents were civil

servants, and 4% were entrepreneur.

The Impact of Motivation on Collaborative Consumption Through Behavioral Intention in Taiwan

75

4.1 Outer Model Assessment

Source: Smart-PLS Output

Figure 1.1: Construct Model.

4.2 Validity and Reliability

Table 1.3: Item Loadings.

Variable Indicator Item

Loadin

g

Safety SY1 0.823 Valid

SY2 0.782 Valid

SY3 0.851 Valid

SY4 0.755 Valid

Social

acceptance

SA1 0.808 Valid

SA2 0.864 Valid

SA3 0.865 Valid

SA4 0.830 Valid

SA5 0.850 Valid

Stimulation SN1 0.807 Valid

SN2 0.873 Valid

SN3 0.894 Valid

Ethics ES1 0.858 Valid

ES2 0.927 Valid

ES3 0.905 Valid

Quality QY1 0.785 Valid

QY2 0.873 Valid

QY3 0.882 Valid

QY4 0.808 Valid

Value for

money

VFM1 0.785 Valid

VFM2 0.842 Valid

VFM3 0.885 Valid

VFM4 0.741 Valid

Comfort CT1 0.889 Valid

CT2 0.798 Valid

CT3 0.868 Valid

Sustainability STY1 0.703 Valid

STY2 0.899 Valid

STY3 0.888 Valid

STY4 0.915 Valid

STY5 0.883 Valid

Attitude ATT1 0.795 Valid

ATT2 0.886 Valid

ATT3 0.871 Valid

ATT4 0.740 Valid

Behavioral

Intention

BI1 0.919 Valid

BI2 0.924 Valid

BI3 0.876 Valid

BI4 0.903 Valid

Source: Smart-PLS Output

Convergent validity can be seen from the loading

factor for each construct indicator. The rule of thumb

used to assess convergent validity is that the loading

factor value must be greater than 0.50. Based on table

1.3 can be seen that all indicator items have a loading

factor value above 0.50, so that all question items

used in this study are valid.

The construct reliability test comes after the

construct validity test and is based on the Composite

Reliability (CR) structure from the indicator block,

which is used to demonstrate good reliability. A

construct is declared reliable if the composite value is

reliable or Cronbach's Alpha> 0.7. Cronbach’s alpha

with a value of 0.60 to 0.07 which can be accepted in

explanatory research, while for more advanced, the

ISCP UTA’45 Jakarta 2022 - International Seminar and Call for Paper Universitas 17 Agustus 1945 Jakarta

76

value must be counted from 0.70 to 0.90 can be said

as satisfactory (Hair, Hult, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2017).

Table 1.4: Composite Reliability (CR).

Variable CR Value Result

Safety 0.880 Reliable

Social acceptance 0.925 Reliable

Stimulation 0.894 Reliable

Ethics 0.925 Reliable

Quality 0.904 Reliable

Value for money 0.888 Reliable

Stimulation 0.889 Reliable

Comfort 0.934 Reliable

Attitude 0.895 Reliable

Behavioral Intention 0.948 Reliable

Source: SmartPLS Output

Table 1.5: R-squared coefficients.

Variable R-Square

Attitude 0.722

Behavioral Intention 0.766

Source: SmartPLS Output

Based on table 1.5 , the R2 value in Taiwan for

attitude variable is 0.722, it means that 72.2% of

variations or changes in attitude are influenced by

safety, social acceptance, stimulation, ethics, quality,

value for money, comfort and sustainability, while the

rest or 27.8% explained by other reasons such as

purchase reference (Hidayat, Kumadji, & Sunarti,

2016). Based on this, the results R2 show that the

influence of motivation on attitude variable is

moderate. The results of the calculation of R

2

show

that R

2

on the Behavioral Intention variable is

substantial

Besides looking at the R-square value, the model

is also evaluated by looking at the predictive

relevance Q-square for the constructive model. The

Q-square measures how well the observed value is

generated by the model and also the parameter

estimates (Hair, Hult, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2017). The

quantity of Q2 has a range value of 0 <Q2 <1, where

the closer to 1 means that the model is getting better.

The magnitude of Q2 is equivalent to the total

coefficient of determination in the path analysis. The

value of Q2> 0 indicates that the model has predictive

relevance, conversely if the value of Q2 ≤ 0 indicates

that the model has less predictive relevance.

Table 1.6: Q

2

Value.

Variable Q

2

Attitude 0.459

Behavioral

Intention

0.605

Source: SmartPLS Output

Based on the results of the above calculations, it

is known that the Q-Square value in Taiwan for

attitude is 0.459 and behavioral intention is 0.605.

The result shows that the model has predictive

relevance.

Table 1.7: Path Coefficients.

Original

Sample

(O)

Sample

Mean (M)

Standard

Deviation

(STDEV)

T Statistics

(|O/STDEV|)

P Values

Safety ->

Attitude

0.450 0.448 0.085 5.286 0.000*

Social

acceptance ->

Attitude

0.053 0.051 0.074 0.710 0.478

Stimulation ->

Attitude

0.216 0.222 0.077 2.810 0.005*

Ethics ->

Attitude

0.332 0.334 0.066 4.995 0.000*

Quality ->

Attitude

-0.018 -0.023 0.095 0.194 0.846

Value for

money ->

Attitude

0.246 0.248 0.075 3.295 0.001*

Comfort ->

Attitude

-0.146 -0.146 0.079 1.844 0.066

Sustainability -

> Attitude

-0.168 -0.170 0.061 2.753 0.006*

Safety ->

Behavioral

Intention

0.075 0.070 0.093 0.809 0.419

Social

acceptance ->

Behavioral

Intention

0.313 0.308 0.071 4.433 0.000*

Stimulation ->

Behavioral

Intention

-0.068 -0.076 0.079 0.867 0.386

Ethics ->

Behavioral

Intention

-0.014 -0.009 0.068 0.207 0.836

Quality ->

Behavioral

Intention

0.147 0.148 0.120 1.221 0.223

Value for

money ->

Behavioral

Intention

-0.013 -0.006 0.068 0.194 0.846

Comfort ->

Behavioral

Intention

0.365 0.361 0.088 4.166 0.000*

Sustainability -

> Behavioral

Intention

0.201 0.202 0.078 2.591 0.010*

Attitude ->

Behavioral

Intention

-0.070 -0.060 0.069 1.006 0.315

Source: SmartPLS output

The Impact of Motivation on Collaborative Consumption Through Behavioral Intention in Taiwan

77

Table 1.7 shows the results of PLS calculations

which state the direct influence between variables.

The result can be stated as follows:

1. The safety variable has a significant effect on the

Attitude variable with T Statistics value 5.286 >

1.96. Business activities must give confidence to

users about safety mechanisms to reduce risk of

renting and swapping (Albinsson & Perera, 2018).

By collecting the fingerprints of drivers, the

identity and criminal background of drivers are

verified in an attempt to protect the safety of

drivers. Uber and Lyft have opposed the

collection of fingerprints and refused to comply

with the new safety regulations imposed by

Austin, Texas.

2. The Stimulation variable has a significant effect

on the Attitude variable with T Statistics value

2.810 > 1.96.

3. Ethics variable has a significant effect on the

Attitude variable with T Statistics value 4.995 >

1.96.

4. The variable Value for money has a significant

effect on the Attitude variable with T Statistics

value 3.295 > 1.96.

5. Sustainability variable has a significant effect on

the Attitude variable with T Statistics value 2.753

> 1.96.

6. The social acceptance variable has a significant

effect on the Behavioral Intention variable with T

Statistics value 4.433 > 1.96. In an examination of

automobile leasing, Trocchia and Beatty (2003)

find that desire for variety, simplified

maintenance, and social approval motivate

behavior.

7. The Comfort variable has a significant effect on

the Behavioral Intention variable with T Statistics

value 4.166 > 1.96.

8. Sustainability variable has a significant effect on

the Behavioral Intention variable with T Statistics

value 2.591 > 1.96.

4.3 Model Fit

The GoF index is used to validate the overall model

(Tenenhaus & Sarstedt, 2012). This index is

developed to evaluate measurement models and

structural models, as well as provide an overall

measurement of the model predictions.

The SRMR is defined as the root mean square

discrepancy between the observed correlations and

the model-implied correlations. Because the SRMR is

an absolute measure of fit. When applying CB-SEM,

a value less than 0.08 is generally considered a good

fit (Hu & Bentle, 1998).

Table 1.9: Fit Summary Taiwan.

Saturated Model

SRMR 0.091

d_ULS 6.491

d_G 3.322

Chi-Square 3,312.092

NFI 0.634

Source: SmartPLS output

Based on table 1.9, RSMR value for Taiwan

model is 0.091 > 0.08 which means the value is

considered not a good fit. Note that early suggestion

for PLS-based GoF measures such as the “goodness-

of-fit” (Tenenhaus & Sarstedt, 2012).

4.4 Hypothesis

Here is the table for summarize all hypothesis results:

Table 1.10: Hypotheses summarized.

Hypothesis Path Results

H1a

Safety ->

Attitude

Supported

H2a

Social

acceptance ->

Attitude

Not-supported

H3a

Stimulation ->

Attitude

Supported

H4a

Ethics ->

Attitude

Supported

H5a

Quality ->

Attitude

Not-supported

H6a

Value for

money ->

Attitude

Supported

H7a

Comfort ->

Attitude

Not-supported

H8a

Sustainability -

> Attitude

Not-supported

H1b

Safety ->

Behavioral

Intention

Not-supported

H2b

Social

acceptance ->

Behavioral

Intention

Supported

H3b

Stimulation ->

Behavioral

Intention

Not-supported

H4b

Ethics ->

Behavioral

Intention

Not-supported

ISCP UTA’45 Jakarta 2022 - International Seminar and Call for Paper Universitas 17 Agustus 1945 Jakarta

78

H5b

Quality ->

Behavioral

Intention

Not-supported

H6b

Value for

money ->

Behavioral

Intention

Not-supported

H7b

Comfort ->

Behavioral

Intention

Supported

H8b

Sustainability -

> Behavioral

Intention

Supported

H9

Attitude ->

Behavioral

Intention

Not-supported

From table 1.10, safety to attitude variable which

states that the result is significant and positive. It can

be interpreted that consumers will think about

harmonization and stability such as improving

security, problem solving, feeling safe, and thinking

about future needs before assessing CC products.

Second is the relationship between the

sustainability on behavioral intention variable. It

indicates that minimizing selling prices, considering

the implications for the community, effectiveness,

efficiency, and responsibility to the environment are

influence the customers’ behavior toward CC

products.

Third, the relationship of stimulation to attitude

variable indicate users do some assessment for CC

products that should be modern, interesting, and over

unique experience.

Fourth, the effect of ethics on attitude occurred

indicates that Taiwan consumers concern about

moral, personal principle, and personal obligation on

assessing CC products.

Fifth, the relationship of value for money to

attitude is significantly positiv means reasonable

price, good choice, and good return to avoiding

wasting money are important as a represent of user’s

assessment for using CC products.

Sixth, social acceptance variable has a positive

and significant impact on behavioral intention means

impression or commonly known product, consumer’s

friend expected to use that kind of product, it has a

good impression, and accepted by the society are

important for represent user’s assessment.

Seventh, the impact of sustainability variable to

behavioral intention has a positive and significant

indicates that reducing the price, impact to

community, efficiency, effectiveness, and

environmental responsibility are important to their

subjective probability for performing behavior.

Another important finding is about the

relationship between the attitudes on behavioral

intention variable which founded insignificant means

that attitude-behavioral intention gap occurs in this

study. The discussion leads to the background why

consumers say something but do different things.

Some possibilities that occur are too much

information or lack of information. Information

overload or underload sometimes becomes a conflict

and creates uncertainty for action. Such as, having to

do R3 (reduce, reused, recycle) properly, buy organic

food ingredients, don't eat meat, avoid products from

certain countries.

The incident in Taiwan to invite the boycott of the

film Mulan from Disney (Everington, 2020).

Therefore, the complex interrelationships between

goals and actions for ethical consumption that are

contemplated in all consumption decisions and

considerations of impact are overwhelming.

The other reason is because social demands paced

on consumers. At the level of relations, individuals

think about their actions that are limited by others. In

this case, consumption decisions must be negotiated

and see the conditions of others. Various studies

illustrate where consumption is more often seen as a

selfish activity. When it should be seen in terms of

satisfaction in meeting one's own demands, intimate,

and distant others (Shaw, Chatzidakis, Goworek, &

Carrington, 2016).

5 CONCLUSIONS

The phenomenon of collaborative consumption

changes many things in terms of individuals,

businesses, communities, and even regions. This is

interesting because the CC trend seems to be growing.

Therefore, anything that affects consumers is an

important thing to understand.

1. The majority of respondents were choosing

delivery services as the most frequently used CC

products.

2. Most of variations or changes in attitude are

influenced by safety, social acceptance,

stimulation, ethics, quality, value for money,

comfort and sustainability, while the rest is

explained by other reasons such as purchase

reference. It is in the moderate category. Based on

the results, most of the respondents agree that

changes in behavioral intention are influenced by

safety, social acceptance, stimulation, ethics,

quality, value for money, comfort, sustainability

and attitude while the rest explained by other

reasons for example, trust, variety of service, e-

The Impact of Motivation on Collaborative Consumption Through Behavioral Intention in Taiwan

79

WoM, perceived risks (Aruan & Felicia, 2019;

Septiani, et al., 2017).

3. The motivational variables that have positive

effect on consumer attitudes are safety,

stimulation, ethics, and sustainability.

4. Then, the motivational variables that have

positive effects on BI are social acceptance,

comfort, and sustainability.

5.1 Managerial Implication

There is some information which can be used for

collaborative consumption providers to start or to

develop their business based on this research.

1. The results said that if the feeling of seeking

harmony and stability is important for the positive

assessment of the product (Bardi & Johansson,

2017) So the business owner should pay attention

to security of the product. They have to make sure

about customers private data not leak. Trusted a

financial guarantor institution to ensure customer

funds is also necessary for online payment

methods.

2. The provider has to make sure that their product

can help people to solve their problem. For new

start-up, it will be better if they have market

research to see clearly about the consumer needs.

3. Respondents also concern of sustainability factor.

They willing to participate, willing to use the

platform more often, and sharing positive

recommendation for people based on

sustainability factor. Providers could create the

opportunities or event for community. For

example, the provider can hold a bazaar for local

food & beverage sectors. It can increase the

behavioral intention of consumers for taking care

of small community-based businesses.

5.2 Limitation and Suggestion

Finally, a number of potential issues need to be

considered below:

1. This study sees CC as a whole regardless of their

business sectors. Basically, products from the

same sector might have a difference, maybe in

terms of service, quality, or target market.

2. In line with Hamari, Sjöklint, & Ukkonen (2015),

that the gap between attitude and behavioral

intention which may be caused by cultural factors

is still large and research literature is still very

limited.

3. Sustainability is still the main attraction for

consumers in using CC products.

Furthermore, some suggestion for other scholar to

broader research finding related with collaborative

consumption or to stakeholder of CC products to have

more understanding about their market.

1. Using specific products or sectors such as

transportation or crowdfunding will be very

interesting considering that this topic is still

developing in terms of products and

community/consumers.

2. The other scholars might have interest in the

attitude-behavior gap that happened not only on

this study. It possibly related with the culture of

market (i.e. language, ideology, or structure of

community). Some of the researches even suggest

to use trust as a mediator between motivation and

behavioral intention.

3. This research gives confidence that consumers

support products that are good for the

environment / uplifted community. This can be

one of the considerations for business owners or

marketers to create or develop product with a

concern of sustainability.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior.

Organizational behavior and human decision processes,

50(2), 179-211.

Albinsson, P. A., & Perera, B. Y. (2012). Alternative

marketplaces in the 21st century: Building community

through sharing events. Journal of Consumer

Behaviour, 11(4), 303-315.

Aruan, D. T., & Felicia, F. (2019). Factors influencing

travelers’ behavioral intentions to use P2P

accommodation based on trading activity: Airbnb vs

Couchsurfing. International Journal of Culture,

Tourism, and Hospitality Research, 1750-6182.

Barbopoulos, I., & Johansson, L.O. (2017). The consumer

motivation scale: Development of a multi-dimensional

measure of economical, hedonic, and normative

determinants of consumption goals. Journal of Business

Research, 76, 118-126.

Bardi, A., & Schwartz, S. H. (2003). Values and Behavior:

Strength and Structure of Relations. Personality and

Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(10), 1207-1220.

Bearden, W. O., Netemeyer, R. G., & Teel, J. E. (1989).

Measurement of consumer susceptibility to

interpersonal influence. Journal of Consumer Research,

15(4), 473-481.

Becker, G. S. (1973). A theory of marriage: Part I. The

Journal of Political Economy, 81, 813-846.

Belk, R. (2010). Sharing. Journal of Vonsumer Research,

36(5), 715-734.

Botsman, R., & Rogers, R. (2010). What’s mine is yours:

The rise of collaborative consumption. New York:

HarperCollins.

ISCP UTA’45 Jakarta 2022 - International Seminar and Call for Paper Universitas 17 Agustus 1945 Jakarta

80

Bray, J., Kilburn, D., & Johns, N. (2011). An exploratory

study into the factors impeding ethical consumption.

Journal of Business Ethics, 98(4), 597-608.

Chin, W. W. (2010). Handbook of Partial Least Squares:

Concepts, methods and applications. In V. V. Esposito

Vinzi, V, W. W. Chin, J. Henseler, & H. Wang,

Springer Handbooks of Computational Statistics (pp.

655-690). Berlin: Springer.

Chulef, A. S., Read, S. J., & Walsh, D. A. (2001). A

hierarchical taxonomy of human goals. Motivation and

Emotion, 22, 191-231.

Eckhardt, G. M., Belk, R., & Devinney, T. M. (2010). Why

don’t consumers consume ethically? Journal of

Consumer Behaviour, 9, 426-436.

Everington, K. (2020, September 6). Taiwanese call for

boycott of Disney's 'Mulan'. Retrieved from

www.taiwannews.com.tw:

https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/en/news/4002974

Fulco, C. P., Munschauer, M., Anyoha, R., Munson, G.,

Grossman, S. R., Perez, E. M.., Kane, M., Cleary,

Brian., Lander, E.S., Engreitz, J. M. (2016). Systematic

mapping of functional enhancer–promoter connections

with CRISPR interference. Science, 354(6313), 769-

773.

Gansky, L. (2010). The mesh: Why the future of business

is sharing. New York: Penguin Group.

Gaur, S. S., & Xu, Y. (2009). Consumer Comfort and Its

Role in Relationship Marketing Outcomes: An

Empirical Investigation. Advances in Consumer

Research, 8, 296-298.

Goldstein, N. J., Cialdini, R. B., & Griskevicius, V. (2008).

A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to

motivate environmental conservation in Hotels. Journal

of Consumer Research, 35, 472-482.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017).

A primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation

Modeling (PLS-SEM) (Second ed.). Thousand Oaks:

SAGE Publications Ltd.

Hamari, J., Sjöklint, M., & Ukkonen, A. (2016). The

sharing economy: Why people participate in

collaborative consumption. Journal of the Association

for Information Science and Technology, 67(9), 2047-

2059.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Henning, V., & Sattler, H. (2007).

Consumer file sharing of motion pictures. Journal of

Marketing, 1-34.

Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS

path modeling in new technology research: updated

guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems,

116(1), 2-20.

Hidayat, A. R., Kumadji, S., & Sunarti. (2016). Analysis of

factors affecting consumer attitudes toward mobile

advertising (Survey on Brawijaya University

2012/2013 class of Administrative Sciences

undergraduate students using LINE Application).

Jurnal Administrasi Bisnis, 35(1), 137-144.

Hill, R. J., Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1977). Belief, attitude,

intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and

research. Social Psychology, 6(2), 244-245.

Hu, J., Liu, Y.-L., Yuen, T. W., Lim, M. K., & Hu, J.

(2019). Do green practices really attract customers?

The sharing economy from the sustainable supply chain

management perspective. Resources, Conservation &

Recycling, 149, 177-187.

Hu, L., & Bentle, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance

structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized

model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4),

424-453.

InsightXplorer. (2018). Taiwan Internet Report. Taipei:

Taiwan Network Information Center.

Janadari, M., Ramalu, S. S., & Wei, C. (2018). Evaluation

of measurement and structural model of the reflective

model constructs in PLS - SEM. The Sixth (6th)

International Symposium of South Eastern University

of Sri Lanka (pp. 187-194). Oluvil: researchgate.net.

Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world,

unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social

Media. Business Horison, 53, 59-68.

Keiler, M. L. (1959). Motivation versus Stimulation. Art

Education, 12(9), 6-13.

Kong, Y., Wang, Y., Hajli, S., & Featherman, M. (2019). In

Sharing economy we trust: Examining the effect of

social and technical enablers on millennials’ trust in

sharing commerce. Computers in Human Behavior, 1-

10.

Lakhani, K. R., & Wolf, R. G. (2005). Why hackers do what

they do: Understanding motivation and effort in

free/open source software projects. In J. Feller, B.

Fitzgerald, S. Hissam, & K. R. Lakhani, Perspectives

on free and Open Source software (pp. 3-21).

Cambridge: MIT Press.

Lawson, S. (2010). Transumers: Motivations of non-

ownership consumption. Advances in Consumer

Research, 37, 842-853.

Lindenberg, S. (2001). Intrinsic motivation in a new light.

Kyklos, 54(2/3), 317-342.

Luchs, M., Naylor, R. W., Rose, R. L., Catlin, J. R., Gau,

R. (2011). Toward a sustainable marketplace:

Expanding options and benefits for consumers. Journal

of Research for Consumers(19), 1-12.

Marzuki, A., Hashemi, S., & Kiumarsi, S. (2017). Tourist's

motivation and behavioural intention between sun and

sand destinations. International Journal of Leisure and

Tourism Marketing, 5(4), 319-337.

Matzler, K., Veider, V., & Kathan, W. (2015). Adapting to

the sharing economy. MIT Sloan Management Review,

72-77.

Nov, O. (2007). What motivates Wikipedians?

Communications of the ACM, 50(11), 60-64.

Nov, O., Naaman, M., & Ye, C. (2010). Analysis of

participation in an online photo-sharing community: A

multidimensional perspective. Journal of the American

Society for Information Science and Technology,

61(3), 555-566.

Oreg, S., & Nov, O. (2008). Exploring motivations for

contributing to open source initiatives: The roles of

contribution context and personal values. Computers in

Human Behavior, 24, 2055-2073.

The Impact of Motivation on Collaborative Consumption Through Behavioral Intention in Taiwan

81

Phipps, M., Ozanne, L. K., Michael, L. G., Subrahmanyan,

S., Kapitan, S., Catlin, J. R., Gau, R., Naylor, R, W.,

Rose, R,L., Simpson, B., Weaver, T. (2013).

Understanding the inherent complexity of sustainable

consumption: A social cognitive framework. Journal of

Business Research, 66, 1227-1234.

Pietro , L. D., & Pantano, E. (2012). An empirical

investigation of social network influence on consumer

purchasing decision: The case of Facebook. Journal of

Direct, Data and Digital Marketing Practice, 14, 18-29.

Prothero, A., Dobscha, S., Freund, J., Kilbourne, W. E.,

Luchs, M. G., Ozanne, L. K., & Thøgersen, J. (2011).

Sustainable consumption: Opportunities for consumer

research and public policy. Journal of Public Policy &

Marketing, 3(1), 31-38.

Rindfleisch, A., & Burroughs, J. E. (2004). Terrifying

thoughts, terrible materialism? Contemplations on a

terror management account of materialism and

consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology,

14(3), 219–224.

Sacks, D. (2011, April 11). The sharing economy.

Retrieved from Fast Company:

http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/155/the-

sharingeconomy.html

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and

structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical

tests in 20 countries. Advances in experimental social

psychology, 25, 1-65.

Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research methods for

business: A skill building approach (7 ed.). Chichester:

John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Septiani, R., Handayani, P. W., & Azzahro, F. (2017).

Factors that affecting behavioral intention in online

transportation service: Case study of GO-JEK. Procidia

Computer Science, 124, 504-512.

Shaw, D., Chatzidakis, A., Goworek, H., & Carrington, M.

(2016, July 28). Explaining the attitude-behaviour gap:

Why consumers say one thing but do another. Retrieved

from www.ethicaltrade.org:

https://www.ethicaltrade.org/blog/explaining-attitude-

behaviour-gap-why-consumers-say-one-thing-do-

another

Sweeney, J. C., & Soutar, G. N. (2001). Consumer

perceived value: The development of amultiple item

scale. Journal of Retailing, 77, 203-220.

Tenenhaus, M., & Sarstedt, M. (2012). Goodness-of-fit

indices for partial least squares path modeling.

Computational Statistics, 28(2), 565-580.

Trocchia, P. J., & Beatty, S. E. (2003). An empirical

examination of automobile lease vs finance

motivational processes. Journal of Consumer

Marketing, 20(1), 28-43.

Uysal , M., & Jurowski, C. (1994). Testing the push and

pull factors. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(4), 844-

846.

Vermeir, I., & Verbeke , W. (2006). Sustainable food

consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude –

behavioral intention” gap. Journal of Agricultural and

Environmental Ethics, 19, 169-194.

Wang, C., & Zhang, P. (2012). The evolution of social

commerce: The people, management, technology, and

information dimensions. 51, 105-127.

ISCP UTA’45 Jakarta 2022 - International Seminar and Call for Paper Universitas 17 Agustus 1945 Jakarta

82