A Psychobiological Model for the Neurological Symptoms in Somatic

Symptom Disorder

Yutong Xu

Keystone Academy, Beijing 101318, China

Keywords:

Somatic Symptom Disorder, Cause of SSD.

Abstract: Current research lacks in synthesis of psychological and biological approaches when studying the mechanism

of somatic symptom disorder (SSD), which impedes the development of effective treatment intervention.

Primarily due to the conflicting perspectives of the two fields. This paper derived a model that combines both

psychological and biological factors by analyzing literature about factors causing development of SSD. Three

neurological symptoms of SSD were analyzed in this paper (headache, dizziness, and weakness) using 19

pieces of studies. The result shows that the development of SSD follows the path of external stimuli –

physiological change – cognitive processing – response – recurrence. Based on the result, a psychobiological

model of SSD development is established. It will help to find a more precise target for SSD treatment.

1 INTRODUCTION

Although modern medicine has made remarkable

progress in curing diseases over the past century,

there is still a range of symptoms that cannot be fully

resolved. Somatic symptom disorder (hereinafter

referred to as SSD) is a typical category. When

patients report discomfort, but a medical inspection

cannot determine its cause, the complaint may be

ascribed to the psychological status of patients and

diagnosed as SSD. Terms such as somatization,

somatization disorder, somatoform disorder, and

somatization syndrome, have all been used in early

studies to describe SSD. Currently, SSD is defined as

“distressing somatic symptoms plus abnormal

thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in response to these

symptoms” (American Psychiatric Association,

2013). A diagnosis of other medical conditions might

or might not be present for patients with SSD. It is

believed that SSD is caused by the interaction of

biological and psychological factors, but the specific

mechanism behind SSD still needs more

understandings due to the miscellaneous physical

expressions and interlaced causes of SSDs.

The diagnostic criteria of SSD in DSM-V are

shown in Table 1. It was improved from the criteria

in DSM-IV, which attributes SSD mainly to the

psychological factors and suggests that somatic

symptoms of patients are illusions caused by their

mental disorder since their somatic discomfort lacks

medical explanation. According to DSM-V, the

patient’s self-reported somatic distress is real,

regardless of the presence or absence of medical

explanation. Moreover, diagnosis of SSD does not

conflict with other medical diagnoses – in fact, SSD

is usually accompanied by other medical conditions

(American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Table 1: Diagnostic Criteria of Somatic Symptom Disorder in DSM-V (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

A. One or more somatic symptoms that are distressing or result in significant disruption of daily life.

B. Excessive thoughts, feelings, or behaviors related to the somatic symptoms or associated health concerns as

manifested by at least one of the following:

1. Disproportionate and persistent thoughts about the seriousness of one’s symptoms.

2. Persistently high level of anxiety about health or symptoms.

3. Excessive time and energy devoted to these symptoms or health concerns.

C. Although any one somatic symptom may not be continuously present, the state of being symptomatic is

persistent (typically more than 6 months).

270

Xu, Y.

A Psychobiological Model for the Neurological Symptoms in Somatic Symptom Disorder.

DOI: 10.5220/0012019500003633

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Biotechnology and Biomedicine (ICBB 2022), pages 270-277

ISBN: 978-989-758-637-8

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Common symptoms of SSD may be categorized

into 1) pain, 2) neurological symptoms, 3) digestive

symptoms, 4) sexual symptoms (Cleveland Clinic,

2018). Pain has been the most commonly reported

symptom, hence most thoroughly studied by previous

researchers. This paper would therefore discuss the

neurological symptoms of SSD. Neurological

symptoms of SSD include headaches, weakness,

dizziness, and abnormal movements (Cleveland

Clinic, 2018). Compared to localized pain, these

symptoms are non-specific, which means the causes

of these symptoms can be associated with a greater

variety of factors.

As mentioned before, SSD is undeterminable by

objective inspections, psychiatrists have to rely on

self-reported experiences of patients, which makes

diagnosis and treatment of SSD problematic. Due to

the complicated nature of SSD, we need to have a

comprehensive understanding of its causes, so that a

better treatment/prevention of SSD could be

developed. Since SSD is a combination of mental

disorders and medical conditions, it is of concern to

both psychiatrists and physicians. However, because

of the discrepancies between professions, previous

researchers have been using different approaches to

study the causes of SSD – psychological and

biological – which are sometimes disagreeing.

Researchers using psychological approaches

explain the cause of SSD mainly by patients’ mental

processing of information and stimuli. Eifert, Lejuez

and Bouman argued that SSD is caused by

individuals' belief about the threatening outcomes of

physiological changes, which is strongly related to

their past learning, including misinterpretation of

medical information, past experiences, perception of

illness, etc (Eifert, 1998). Witthoft and Hiller added

up to that opinion, suggesting that SSD is caused by

individuals' excessive focus on bodily sensations and

exaggerated illness outcomes and that excessive

focus is primarily due to their neuroticism and

suggestibility (Witthöft, 2010).

Researchers using biological approaches explain

the cause of SSD mainly by patient’s physiological

changes. Rief and Barsky proposed a filter system, in

which they argued that SSD is strongly influenced by

biological factors such as physiological arousal,

endocrine imbalance, neurotransmitter disorder, etc

(Rief, 2005). The individual’s selective attention and

pre-existing mental disorder either made them ignore

the primary physiological signal or over-amplify the

signal, thereby causing the symptoms in SSD.

Dimsdale and Dantzer argued more radically,

suggesting that SSD is probably a misdiagnosis due

to ignorance of patients' history, an unrecognized

disease, or misdiagnosis due to not using modern

diagnostic technology (Dimsdale, 2007).

The disagreement between psychological and

biological approaches is not beneficial for the study

of SSD because a single-factor model is not enough

to induce the developmental path of SSD, which may

have been allowed more precise and effective

treatment interventions. The modern behavioral

medicine approach considered both psychological

and biological factors in the mechanism of SSD by

indicating a mutually reinforcing relationship

between physiological disturbance and emotional

arousal, but the focus was on treatment intervention

(Looper, 2002). The model needs more details on the

mechanism of SSD, as well as more specific

connections to symptoms.

One integrated model was created by Flor,

Birbaumar, and Turk in 1990 for the development of

chronic pain. According to their model, the cause of

chronic pain can be divided into four stages (Flor,

1990):

1. Predisposing factor including genetic defect,

previous social learning, trauma, etc;

2. Precipitating stimuli, which are external and

internal stimuli that arouse discomfort feeling;

3. Precipitating responses, referring to the over-

perception of physical symptoms or inadequate

perception of internal stimuli;

4. Maintaining processes, which are the

conditional learning of pain-related fear and

physiological responses as a result of conditional

learning.

Researchers then suggested: recurring stress and

pain episode leads to increased muscle tension, which

leads to insufficient blood and oxygen in affected

muscles, consequently releasing pain-related

substances, finally resulting in muscular and

sympathetic hyperactivity, thereby forming a vicious

cycle (Flor, 1990).

In this paper, an integrated model for the

development of neurological symptoms in SSD is

established based on literature analysis. This paper

will start by reviewing theories with empirical

supports from both psychological and biological

perspectives, then identify major factors that play a

role in the development of each symptom. Finally, a

general developmental path of neurological

symptoms of SSD will be drawn.

A Psychobiological Model for the Neurological Symptoms in Somatic Symptom Disorder

271

2 METHOD

Literature referenced in this paper is drawn from three

databases (PubMed, UpToDate, and NCBI) by

searching “somatization cause”, “somatoform cause”,

“somatic symptom cause”, “chronic headache”,

“muscle weakness”, and “chronic dizziness”. Papers

are excluded if: (1) irrelated with the cause of SSD;

(2) individual case without other empirical supports;

(3) did not refer to any of the three neurological

symptoms; (4) is specific to a group of patients; (5)

published before 2000. The potential factors causing

the three symptoms are extracted from selected

literature and explained in the following section.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Chronic Headache

3.1.1 Pre-Existing Health Issue

Headache is one symptom of anxiety. As patients

with anxiety demonstrate stress responses and are

more vulnerable to external stimuli. Lindsay Allet

and Rachel Allet stated that anxiety level is widely

recognized in relation to headaches (Allet, 2006).

Shim, Aram Park, and Sung-Pa Park did a statistical

analysis to determine whether alexithymia,

somatization, anxiety and depression are factors

causing chronic headaches (Shim, 2018). They found

that these factors are statistically significant in effect

on headache patients. Anderson, Maes, and Berk

stated that somatic symptoms such as pain and

muscular tension, are major comorbidities of

depression (Anderson, 2012).

3.1.2 Cognitive Processing

Shim, Aram Park, and Sung-Pa Park found that

people with alexithymia are more likely to be

associated with tension-induced chronic headaches

(Shim, 2018). Since alexithymia patients are more

self-affective (Saito, 2016) and hence pay more focus

on their own feeling, a more sensitive perception

toward physical change may be expected, thereby

leading to a more frequent report of headache.

Cappucci and Simons measured anxiety sensitivity by

patients’ self-report and discovered that SSD patients

have high anxiety sensitivity (Cappucci, 2014). They

hypothesized a model that anxiety sensitivity leads to

fear of pain and consequently a stronger experience

of pain-related disability.

3.1.3 External Stimuli

Anderson, Maes, and Berk found that cortisol release

under stress situations may increase mu-opioid

transcription and affect the tryptophan pathway,

tryptophan depletion causes photophobia and

headache (Anderson,, 2012). Espinosa Jovel and

Mejia suggested a causal relationship between

individual hyperexcitability and caffeine intake

(Espinosa, 2017). Moreover, excessive caffeine

intake can result in depression and headaches.

Another group of researchers presented a series of

SSD cases after HPV vaccine injections, which are

speculated to be caused by a sympathetic nervous

system dysfunction stimulated by HPV injection in

the susceptible population (Palmieri, 2016). Although

this phenomenon was observed worldwide, data is

still insufficient to draw a causal relationship between

HPV vaccination and SSD.

3.2 Muscular Weakness (Functional

Weakness)

3.2.1 Pre-Existing Health Issue

Shangguan et al. investigated people who developed

anxiety disorder during the Covid pandemic and

found a statistically significant correlation between

stress and anxiety level, and subjective feeling of

muscular weakness (Shangguan, 2020). Chaturvedi,

Maguire, and Somashekar studied SSD in patients

with cancer. Tiredness, exhaustion, and weakness are

frequently reported. The researchers suggested SSDs

may be the symptom of depression in cancer patients

or side effects of radiation treatment (Chaturvedi,

2006). They also found an association between liver

metastasis (tumor) and weakness. Liver dysfunction

seems to be generally associated with energy levels

(Swain, 2006).

3.2.2 Individual Condition

Shangguan et al. also discovered in their study that

females have a stronger statistical association with

subjective somatic symptoms (Shangguan, 2020).

Stone, Warlow, and Sharpe discovered female gender

dominance in cases of muscular weakness (Stone,

2010).

ICBB 2022 - International Conference on Biotechnology and Biomedicine

272

3.2.3 Cognitive Processing

Stone, Warlow, and Sharpe found patients with

functional weakness tend to think their symptom is “a

mystery” and believe that their symptom is

physiological instead of psychological (Stone, 2010).

Observation of medical management of patients with

functional weakness done by Stone and Carson shows

an improved somatic condition of patients after

changing thinking processes from “the symptom is

devastating” to “the symptom is curable.” (Stone,

2011) The fact that change in cognitive processes can

relieve a patient’s condition shows an important role

played by individuals' cognition in SSD.

3.2.4 External Stimuli

Jotwani and Turnbull introduced some cases

suggesting central neuraxial anesthesia may cause

postoperative weakness because some GABA-

containing sedatives may inhibit certain neural

pathways and lead to the symptoms (Jotwani, 2020).

However, the author mentioned data is insufficient to

draw a conclusion. They also added, in their specific

case, the patient seemed to exhibit an unconscious

stress response, which could result in her somatic

symptom. Lack of vitamin-D intake is also related to

muscle weakness (Dawson-Hughes, 2017) and this

argument was backed up by an experiment done on

mice, which discovers muscle weakness of mice with

vitamin-D receptor removed (Girgis, 2019).

3.3 Chronic Dizziness

3.3.1 Pre-Existing Health Issue

Gupta reviewed past studies on the relationship

between post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and

chronic dizziness (Gupta, 2013). It was concluded by

previous studies that one of the features of PTSD is

sleepiness and partial consciousness, which may be

perceived by individuals as dizziness (Gupta, 2013).

Staab stated a relationship between chronic dizziness

and traumatic brain injury. He introduced that many

patients who had undergone traumatic brain injury

reported “subjective dizziness, imbalance,

hypersensitivity to motion cues.” (Staab, 2006)

Cortese et al. analyzed the DNA of 95 patients with

neurological symptoms of imbalance and dizziness.

They discovered a disordered replication of a DNA

unit named RFC1, leading to ataxia, which causes the

symptoms of dizziness (Cortese, 2020). The patients

usually report neurological symptoms at the sixth

year of the onset of ataxia (Cortese, 2020). Hence,

when investigating SSD, patients' history has to be

taken into account.

3.3.2 External Stimuli

Buzhdygan et al. studied the effect of SARS-CoV-2

spike protein on patients' brain activity and found that

this spike protein can affect the blood-brain barrier

function, causing inflammation in endothelium and

leading to neurological symptoms including chronic

dizziness (Buzhdygan, 2020). Fang et al. analyzed

blood samples of patients with chronic dizziness and

discovered a significantly high level of oxidative

stress parameters and emotional stress-related

neurotransmitters (Fang, 2020). They suggested that

the redox system in SSD patients may be impaired.

4 DISCUSSION

It seems that in all three neurological symptoms of

SSD, the cause, or mechanism, is generally the same

and are interrelated. Four significant factors had been

identified: pre-existing health condition, external

stimuli, cognitive processing, and individual

condition.

4.1 Pre-Existing Condition

Most studies addressed depression and anxiety as the

cause of individuals' strong perception of physical

symptoms. Patients with depression disorder are

featured in decreased interest toward the external

environment and lowered self-esteem (Özen, 2010).

Decreased attention to external stimuli means a

higher level of attention on senses of oneself,

therefore depressive individuals are more likely to

experience and exaggerate somatic symptoms.

Lowered self-esteem means an expectancy of

negative experiences, hence negative physiological

changes are more evident for depressive patients.

Moreover, some depressive patients feel they need

more social attention and caring. When they associate

others' attention with their report of discomfort,

reporting SSD would become a learned behavior.

Individuals with anxiety tend to exhibit unnecessary

thoughts and associate negative consequences with

somatic symptoms (over-interpretation). They were

found to be more often associated with

hypochondriasis (Özen, 2010). Just as Shangguan et

A Psychobiological Model for the Neurological Symptoms in Somatic Symptom Disorder

273

al. discovered, individuals with anxiety tend to

exaggerate and frequently report somatic symptoms

(Shangguan, 2020). Also, panic attacks in anxiety

disorder can directly result in sweating,

lightheadedness, headache, dizziness, weakness,

muscle tension, etc. (Better Health Channel, 2020)

Genetic deficits such as metabolic myopathies (Johns

Hopkins, 2021), which is a decrease in muscle

metabolism, can be also expressed as muscular

weakness. Other pre-existing medical conditions like

PTSD or cancer tumors, as referenced in the last

section, are all potential factors causing the symptoms

of SSD.

4.2 External Stimuli

External stimuli are associated with both

psychological and biological responses. A stress

condition can lead to anxiety response, thus the

release of stress-related chemicals, and the

malfunction of neural pathways in SSD patients. It

could be inferred from Anderson, Maes, and Berk’s

study, the amount of cortisol released by SSD patients

is abnormal because normal cortisol metabolism

would not induce neural pathway dysfunction

(Anderson, 2012). Therefore, it is hard to tell whether

the mental status of SSD patients caused them to

amplify changes brought by external stimuli, or the

biological difference/change in their body reacted to

the external stimuli. Other external stimuli might be

strenuous exercise, cold weather, strong light &

sound stimuli, and sleep deprivation. These factors

can lead to change in blood pressure, muscle

contraction, and vascular contraction, which are all

causes of headache and dizziness.

4.3 Cognitive Processing

When a physiological change is perceived, SSD

patients seem to go through a different cognitive

process, either consciously or unconsciously.

According to the model of Eifert, Lejuez, and

Bouman, past learning would cause the individual to

believe in their “state of being ill” and start to use

their coping skills in response to the external

threatening stimuli (Eifert, 1998). The researchers

suggested that illness belief and coping skills are

safety-seeking behaviors. Intuitively, we have to

focus on the threatening stimulus to ensure we are in

a safe condition, and to respond as quickly as

possible. This probably explains why SSD patients

pay much attention to their somatic feeling. In Stone

and Carson’s case, the SSD patients received

psychological counseling to change their thinking

process (Stone, 2011). Their finding shows that when

SSD patients do not view somatic symptoms as risk

factors, their stress responses are reduced (Stone,

2011). This demonstrates the effect of cognitive

processing on symptoms presented by SSD patients.

4.4 Individual Condition

Every individual is different, both biologically and

psychologically. Gender is a significant factor in

SSD. Female is more susceptible to emotional change

and negative external stimuli, sometimes hold a more

self-focused thinking process (Ingram, 1988). The

premenstrual syndrome was found to be strongly

connected with SSD and alexithymia when appeared

together with depression (Kuczmierczyk, 1995).

Other conditions include social environment, like the

epidemic prevention in the society one’s in during

Covid; education, whether or not one knows SSD or

cognitive process or the physiological change they are

experiencing; immunity; fitness; etc.

4.5 A Psychobiological Model Of SSD

From the analysis of factors, a general development

path of neurological symptoms in SSD can be seen:

I. Individual condition determines the one’s

susceptibility

II. External stimuli incite a physiological change

III. The physiological change combines with

individual’s pre-existing condition (if exists) and

perceived by individual

IV. The cognitive processing of individual

determines the strength of their response (SSD patient

respond strongly due to 1/2/3)

V. Self-pressuring/worrying/prolonged symptom

becomes the new stimuli

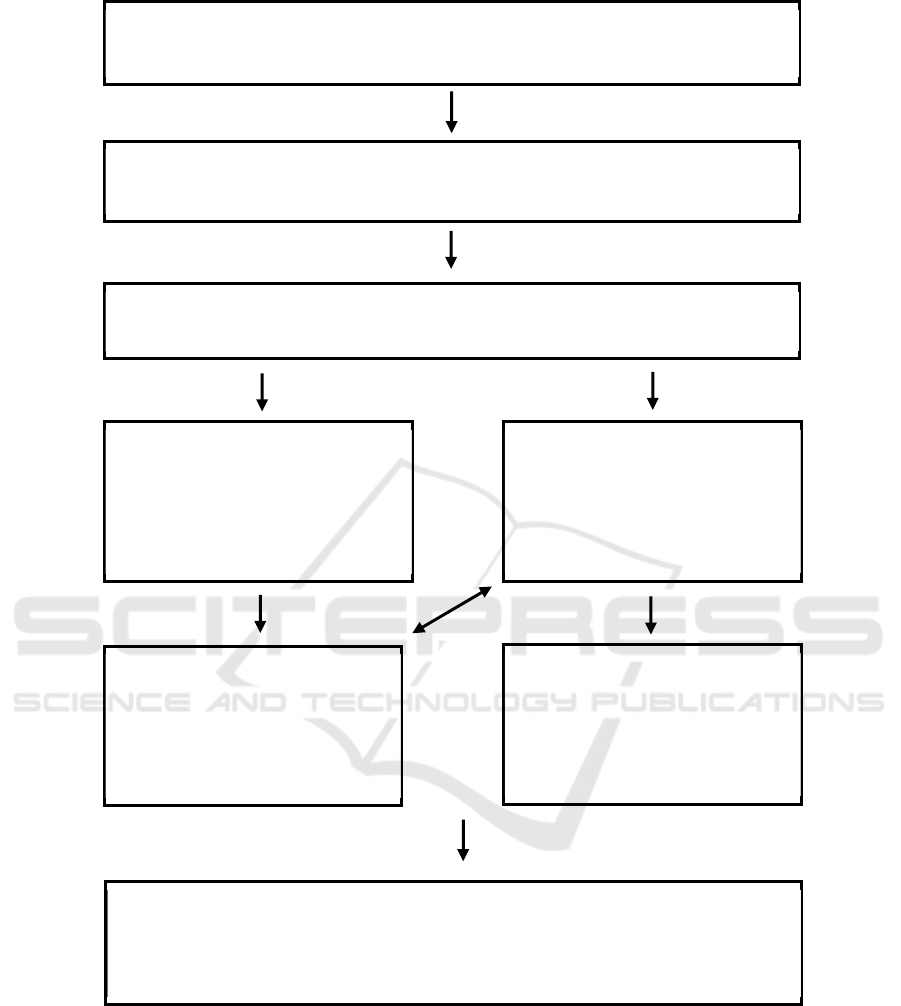

This path is presented visually in Figure 1.

ICBB 2022 - International Conference on Biotechnology and Biomedicine

274

.

Figure 1: Model for Neurological Symptoms Development of SSD.

5 CONCLUSION

In summary, this paper reviewed previous research on

SSD cause and development. This paper found that

external stimuli incite a physical change in SSD

patients, then biological factors, including individual

differences and physical symptoms, are processed by

psychological factors, such as preexisting mental

disorders and cognitive differences, eventually

amplifying patient’s perception of their actual

physical change. This work innovatively considered

three types of factors and combined them into one

model, thereby providing a comprehensive discussion

External stimuli

Exercise, weather change, light, sound, sleep deprivation, medication, etc.

Individual condition

Gender, social environment, education, immunity, fitness, lifestyle, diet, etc.

Physiological change / symptom

Perceive symptom as threat

Pre-existing condition

Depression, anxiety, PTSD, metabolic

myopathies, impaired neural pathway, etc.

Cognitive processing

Past learning, beliefs, social demand,

etc.

(Affected by mental disorders)

Response

Help-seeking behavior, anxiety,

emotional change, sleep change,

hormone imbalance, etc.

Intensified symptom

Or

Increased attention to symptom

Recurring / prolonged symptom

Or

Maintained feeling of the symptom

A Psychobiological Model for the Neurological Symptoms in Somatic Symptom Disorder

275

of SSD development. This work will help researchers

to target a specific point to intervene in disease

development, for example, guide the patient to have

an appropriate cognition of physical discomfort.

Future studies can focus on providing more empirical

support so that a causal relationship between one

factor such as gender, and the response, such as

anxiety, may be derived.

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Somatic

symptom and related disorder. In: Robin, L. C. & Scott,

O. L. (Eds.), Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental

disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed., pp. 309–327). essay,

American Psychiatric Association., Washington. pp.

308 – 312.

Anderson, G., Maes, M., & Berk, M. (2012). Inflammation-

related disorders in the tryptophan catabolite pathway

in depression and somatization. Advances in Protein

Chemistry and Structural Biology Volume 88, 27–48.

https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-398314-5.00002-7

Allet, J. L., & Allet, R. E. (2006). Somatoform disorders in

neurological practice. Current Opinion in Psychiatry,

19(4), 413–420.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.yco.0000228764.25732.21

Better Health Channel. (2020). Panic Attack. Retrieved

December 1, 2021, from

https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsa

ndtreatments/panic-attack.

Buzhdygan, T. P., DeOre, B. J., Baldwin-Leclair, A.,

Bullock, T. A., McGary, H. M., Khan, J. A., Razmpour,

R., Hale, J. F., Galie, P. A., Potula, R., Andrews, A. M.,

& Ramirez, S. H. (2020). The sars-COV-2 spike

protein alters barrier function in 2D static and 3D

microfluidic in-vitro models of the human blood–brain

barrier. Neurobiology of Disease, 146, 105131.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2020.105131

Cappucci, S., & Simons, L. E. (2014). Anxiety sensitivity

and fear of pain in paediatric headache patients.

European Journal of Pain, 19(2), 246–252.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.542

Chaturvedi, S. K., Peter Maguire, G., & Somashekar, B. S.

(2006). Somatization in cancer. International Review of

Psychiatry, 18(1), 49–54.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260500466881

Cleveland Clinic. (2018). Somatic symptom disorder in

adults. Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved December 1, 2021,

from

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17976-

somatic-symptom-disorder-in-adults.

Cortese, A., Tozza, S., Yau, W. Y., Rossi, S., Beecroft, S.

J., Jaunmuktane, Z., Dyer, Z., Ravenscroft, G., Lamont,

P. J., Mossman, S., Chancellor, A., Maisonobe, T.,

Pereon, Y., Cauquil, C., Colnaghi, S., Mallucci, G.,

Curro, R., Tomaselli, P. J., Thomas-Black, G., … Reilly,

M. M. (2020). Cerebellar ataxia, neuropathy, vestibular

areflexia syndrome due to RFC1 repeat expansion.

Brain, 143(2), 480–490.

https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awz418

Dawson-Hughes, B. (2017). Vitamin D and muscle

function. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and

Molecular Biology, 173, 313–316.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.03.018

Dimsdale, J. E., & Dantzer, R. (2007). A biological

substrate for somatoform disorders: Importance of

pathophysiology. Psychosomatic Medicine, 69(9),

850–854.

https://doi.org/10.1097/psy.0b013e31815b00e7

Eifert, G. H., Bouman, T. K., & Lejuez, C. W. (1998).

Somatoform disorders. In M. Hersen, & A. S. Bellack

(Eds.), Comprehensive Clinical Psychology (pp. 543 -

565). Pergamon Press.

Espinosa Jovel, C. A., & Sobrino Mejía, F. E. (2017).

Caffeine and headache: Specific remarks. Neurología

(English Edition), 32(6), 394–398.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nrleng.2014.12.022

Fang, Z., Huang, K., Gil, C.-H., Jeong, J.-W., Yoo, H.-R.,

& Kim, H.-G. (2020). Biomarkers of oxidative

stress and endogenous antioxidants for patients with

chronic subjective dizziness. Scientific Reports, 10(1).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58218-w

Flor, H., Birbaumer, N., & Turk, D. C. (1990). The

psychobiology of chronic pain. Advances in Behaviour

Research and Therapy, 12(2), 47–84.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6402(90)90007-d

Girgis, C. M., Cha, K. M., So, B., Tsang, M., Chen, J.,

Houweling, P. J., Schindeler, A., Stokes, R., Swarbrick,

M. M., Evesson, F. J., Cooper, S. T., & Gunton, J. E.

(2019). Mice with myocyte deletion of vitamin D

receptor have sarcopenia and impaired muscle function.

Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, 10(6),

1228–1240. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12460

Gupta, M. A. (2013). Review of somatic symptoms in post-

traumatic stress disorder. International Review of

Psychiatry, 25(1), 86–99.

https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2012.736367

Ingram, R. E., Cruet, D., Johnson, B. R., & Wisnicki, K. S.

(1988). Self-focused attention, gender, gender role, and

vulnerability to negative affect. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 55(6), 967–978.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.55.6.967

Johns Hopkins. (2021). Metabolic myopathy. Johns

Hopkins Medicine. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-

and-diseases/metabolic-myopathy.

Jotwani, R., & Turnbull, Z. A. (2020). Postoperative

hemiparesis due to conversion disorder after moderate

sedation: A case report. Anaesthesia Reports, 8(1), 17–

19. https://doi.org/10.1002/anr3.12035

Kuczmierczyk, A. R., Labrum, A. H., & Johnson, C. C.

(1995). The relationship between mood, somatization,

and alexithymia in premenstrual syndrome.

Psychosomatics, 36(1), 26–32.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0033-3182(95)71704-2

Looper, K. J., & Kirmayer, L. J. (2002). Behavioral

medicine approaches to somatoform disorders. Journal

ICBB 2022 - International Conference on Biotechnology and Biomedicine

276

of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(3), 810–827.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.70.3.810

Özen, E. M., Serhadlı, Z. N., Türkcan, A. S., & Ülker,

G. E. (2010). Somatization in depression and anxiety

disorders. Dusunen Adam: The Journal of Psychiatry

and Neurological Sciences, 60–65.

https://doi.org/10.5350/dajpn2010230109t

Palmieri, B., Poddighe, D., Vadalà, M., Laurino, C.,

Carnovale, C., & Clementi, E. (2016). Severe

somatoform and dysautonomic syndromes after HPV

vaccination: Case series and review of literature.

Immunologic Research, 65(1), 106–116.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12026-016-8820-z

Rief, W., & Barsky, A. J. (2005). Psychobiological

perspectives on Somatoform Disorders.

Psychoneuroendocrinology, 30(10), 996–1002.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.03.018

Shim, E.-J., Park, A., & Park, S.-P. (2018). The relationship

between alexithymia and headache impact: The role of

somatization and pain catastrophizing. Quality of Life

Research, 27(9), 2283–2294.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1894-4

Saito, N., Yokoyama, T., & Ohira, H. (2016). Self-other

distinction enhanced empathic responses in individuals

with alexithymia. Scientific Reports, 6(1).

https://doi.org/10.1038/srep35059

Shangguan, F., Quan, X., Qian, W., Zhou, C., Zhang, C.,

Zhang, X. Y., & Liu, Z. (2020). Prevalence and

correlates of somatization in anxious individuals in a

Chinese online crisis intervention during covid-19

epidemic. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 436–442.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.035

Swain, M. G. (2006). Fatigue in liver disease:

Pathophysiology and clinical management. Canadian

Journal of Gastroenterology, 20(3), 181–188.

https://doi.org/10.1155/2006/624832

Stone, J., Warlow, C., & Sharpe, M. (2010). The symptom

of functional weakness: A controlled study of 107

patients. Brain, 133(5), 1537–1551.

https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awq068

Stone, J., & Carson, A. (2011). Functional neurologic

symptoms: Assessment and management. Neurologic

Clinics, 29(1), 1–18.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncl.2010.10.011

Staab, J. P. (2006). Chronic dizziness: The interface

between psychiatry and Neuro-Otology. Current

Opinion in Neurology, 19(1), 41–48.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.wco.0000198102.95294.1f

Witthöft, M., & Hiller, W. (2010). Psychological

approaches to origins and treatments of somatoform

disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6(1),

257–283.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.13150

5

A Psychobiological Model for the Neurological Symptoms in Somatic Symptom Disorder

277