How Hukou Affects Precarious Employment: A Quantitative Analysis

of the 2017 Chinese General Social Survey

Tengyi Wang

The Experimental High School Attached to BNU, Beijing, 100032, China

Keywords: Precarious Employment, Hukou, Binary Logistic Regression Model.

Abstract: Technological advancement and economic globalization have made jobs increasingly precarious worldwide,

including in China. Those precarious workers often suffer from employment insecurity, income inadequacy,

and lack of protection. According to the 2021 National Bureau of Statistics, 200 million jobs in the Chinese

labor market fall in the category of precarious employment, accounting for 22.2% of the total labor force. The

Chinese household registration system (hukou), one critical factor in the Chinese labor market, can play an

essential role in shaping precarious employment. However, less literature has quantitatively studied the

relationship between hukou and precarious employment. Based on the 2017 Chinese General Social Survey

(CCGS), this study divides “precariousness” into two indicators—employment status and part-time job

status—and uses binary logistic regression models to examine the association between hukou and precarious

employment. The results show that people holding agricultural hukou are more likely to be in precarious

employment. These findings suggest that policies on employment, compulsory education, and vocational

training should be gradually decoupled from the hukou status in order to break the rural-urban divide.

1 INTRODUCTION

With technological advancement and economic

globalization, jobs have become increasingly

precarious in China and worldwide. The term

“precarious employment” refers to irregular and

insecure work arrangements, including insufficient

salary, hazardous working conditions, low-income

security, and vulnerable labor relations (Kreshpaj et

al., 2020; Rönnblad et al., 2019). Precarious

employment was a distinguished feature in developed

and industrialized countries since the 19

th

century,

and in developing countries after World War II, the

prosperous economy and new legislation protecting

workers legal rights led to a new form of labor

market----the increase of precarious employment

(Tompa et al., 2007). In China alone, according to the

2021 National Bureau of Statistics

1

, there are a total

of 900 million labor force, among which the number

of precarious employment has reached 200 million,

accounting for a large proportion (Guo, 2021).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of

1

http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/sjjd/202201/t20220117_1826

479.html. Access on October 25, 2022.

precarious workers would continue to increase due to

the unstable and rapidly changing labor market

(Yueping et al., 2021). Most literature has examined

the characteristics and the consequences of

precarious employment in developed countries, such

as Germany, America, and Canada (Cranford et al.,

2003; Kalleberg & Vallas, 2018; Vosko, 2006). This

is because those developed countries have a long

history of precarious employment. Since the

industrialization era, they gradually built mature

legislations of the labor market and had mature labor

union systems, which were more advanced than

developing countries (Tompa et al., 2007). Thus, it is

worth studying precarious employment in China

because it is the largest developing country, which

hasn’t been studied thoroughly in this aspect.

This paper examines the characteristics of

precarious employment in the Chinese labor market,

and in particular, the association between household

registration status and precarious employment. The

household registration in China, named the hukou

system, is one major factor in unequal access to

employment in the labor market. In history, hukou

196

Wang, T.

How Hukou Affects Precarious Employment: A Quantitative Analysis of the 2017 Chinese General Social Survey.

DOI: 10.5220/0012072000003624

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Public Management and Big Data Analysis (PMBDA 2022), pages 196-204

ISBN: 978-989-758-658-3

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

was used to control population mobility, separating

workers between urban areas and rural areas. Even

though now the government gradually breaks down

such segregation by liberalizing the restriction that

hukou caused, the labor market divide is rooted in the

society. In particular, the hukou system created

deformed citizenship, which discouraged migrants

from moving, working, and truly integrating into

cities, finally causing them to work in an unstable

situation and to be precarious workers (Ngai, 2010).

So far, most studies on this topic took a qualitative

approach, thus it is useful to examine the association

through a quantitative analysis.

To explore these questions, we use the data from

2017 Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS). CGSS

is one commonly used national presentative survey in

social science research, and the 2017 wave is the most

recent one publicly available. Logistic regression

results show that people with agricultural hukou are

more likely to be precarious workers, who have

statistically significant lower wages and education

levels than people with non-agricultural hukou. These

findings suggest hukou not only causes the wage

discrimination which most of existing literature has

proposed but also leads to the unequal access to

precarious employment in the labor market.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 The Characteristics and the

Consequence of Precarious

Employment

According to the International Labor Organization,

“precarious work is a means for employers to shift

risks and responsibilities onto workers. It is work

performed in the formal and informal economy and is

characterized by variable levels and degrees of

objective (legal status) and subjective (feeling)

characteristics of uncertainty and insecurity.”

However, as the development of labor markets

worldwide, the definition ILO proposed is too broad

to use, thus the academic area does not have a

common definition now. Hence, this study will

examine some core characteristics of precarious

employment first.

There are several definitions of precarious work in

the literature. The characteristics of precariousness in

the labor relation can be concluded in three

dimensions: employment insecurity, income

inadequacy, and lack of protection (Kreshpaj, 2020).

Burgess and Campbell (1998) used a comprehensive

perspective to define precariousness so that it can

assess all kinds of precarious employment, finding

that precariousness is featured in the discontinued,

unprotected job, which is excluded from standard-

employment benefits. Under the definition, the word

“precarious” infers casual, family work, fixed-term

contracts, self-employed, or temporary work.

Simultaneously, it described the condition of such

work, like insufficient salary, hazardous working

conditions, low-income security, and vulnerable labor

relations (Kreshpaj et al., 2020; Rönnblad et al., 2019).

In addition to the study above, lots of literature also

examines the descriptions of precarious employment.

Quinland (2012) demonstrated that the term

“precarious employment” is often used to describe

irregular and insecure work arrangements. Tompa

(2007) supposed that it should be defined as an

unstable, unprotected, insecure, and vulnerable

working status. In addition, Benach (2000) considered

precarious employment as temporary work or

insecure and informal jobs. Through all these

descriptions, we can conclude that precarious

employment is defined by some key features, such as

casual, family work, fixed-term contracts, self-

employed, or temporary work, poor working

conditions, and lack of legal or insurance protections.

Besides, based on the comprehensive

characteristics and features of precarious employment,

lots of literature studied the consequences of it. Some

research shows that there is a strong association

between precarious employment and unideal health

outcomes, including physical health and mental health.

It was found that precarious employment caused a

significant decline in workers” well-being and mental

health due to the unstable nature of the jobs (Gunn et

al., 2021; Rönnblad et al., 2019). Benach and

Muntaner (2007) believed that many characteristics

attached to precarious employment, like low

credentials, low salary, and identity of migrants, are

the main factors that cause workers’ adverse health

outcomes. In addition to the findings of the

relationship between health situations and precarious

employment, Oddo (2021) discovered that people

who have lower income or are female, racialized, or

less educated are more likely to be precarious workers

in America. The scoping review of Gray (2021) also

supported this conclusion and added that the identity

of migrant workers may cause workers to be

precarious and fall into the secondary labor market,

known as an insecure working situation, low income,

and lack of protection. However, according to Brady

and Biegert (2017), in Germany, variables

like demographic, education/skill, job/work

characteristics, and region cannot successfully explain

How Hukou Affects Precarious Employment: A Quantitative Analysis of the 2017 Chinese General Social Survey

197

the growth of precarious employment, so institutional

alternation looks like the most credible illustration.

2.2 Hukou and Precarious

Employment in China

The work of precarious employment in China has

been cumulating in recent years, and most of the

literature focus on labor relations, legal risks, social

security, and their impacts on workers’ well-being

(Benach et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2022; Ding, 2017; Liu,

2022; Du, 2020; Zhang, 2022; Qi et al., 2022; Wang,

2021; Zhao, 2022; Shao, 2022; Guo, 2021). For

example, Liu (2022) explored the identity of

precarious workers. She found that departed from

traditional “employer-employee” labor relations

precarious workers often have part-time jobs, weak

dependence, less monitoring, and a lower degree of

working sustainability. In addition, Shao (2022) did

comprehensive research on the tax risks of precarious

workers from the perspective of both workers and

companies. Discovering the lack of compliance with

tax rules, such as false invoicing, tax evasion, and

ambiguity taxing, Shao proposed some practical and

valuable suggestions on precarious employment, like

standardizing invoice mechanisms and building

external tax risk management. Like most of the

existing literature on precarious employment, Zhang

and Ding (2017; 2020) studied precarious workers’

willingness to join social security and old-age

insurance. They revealed that the mode of

participation and transfer and the incentive method are

the problems that restrict precarious employees from

taking part in insurance. Hence, they suggested

improving the accessibility of insurance policies and

fostering the propaganda of insurance. In conclusion,

precarious workers often suffer from an insecure

working situation, low income, and lack of protection,

known as the secondary labor market.

In China, in addition to the factors and

consequences above that influence precarious

employment, household registration status (hukou) is

a critical structural force shaping the labor market

outcomes, partly explaining the income inequality and

vocational separation in the labor market. Hukou is an

institution with the capacity to monitor and control

population migration and access to public services

(Wu & Zhang, 2014). Personal hukou for all Chinese

citizens is divided into two categories: hukou type and

hukou location. The hukou type is classified as

agricultural hukou or non-agricultural hukou, usually

referring to rural or urban hukou, respectively (Knight

et al., 1999). Another category is hukou location,

which means each person is also classified based on

where he or she registered for hukou.

So how does hukou influence the labor market?

Abundant literature shows that hukou discrimination

exists in the labor market, leading to differences in

income and vocations between people with

agricultural hukou and people with non-agricultural

hukou. On the one hand, hukou discrimination makes

it difficult for people with agricultural hukou to enter

specific sectors, industries, and occupations. On the

other hand, different departments and industries have

different requirements for human capital, which may

lead to the clustering of people with agricultural hukou

with low average human capital and urban workers

with relatively high human capital in different

departments, industries, and occupations (Xie, 2012).

Hence, by combining these two approaches, hukou

discrimination exists in the labor market, and people

with agricultural hukou have lower wages than non-

rural hukou holders. This result was also supported by

other research (Chen et al., 2016; Zhang & Wang,

2011). For example, Liu (2005), using data from a

Chinese household survey, discovered that people

obtaining urban hukou later in their lives are more

probably to be self-employed or unemployed than

people who born with urban hukou. Song (2014) also

pointed out that people with rural hukou face labor

discrimination in cities, including wage

discrimination, hiring discrimination, and pre-market

discrimination. Xu (2004), in his paper, suggested that

hukou discrimination in the labor market was caused

by political restriction, which was rooted in the

planned economy, path independence, education

segregation, and information asymmetry. Based on the

statistical examination, Xu proposed that human

resources cannot explain the income inequality

between people with agricultural hukou and people

with non-agricultural hukou. Therefore, consistent

with the analysis of the dual labor market, the hukou

segregation embodied in the labor market may be

caused by institutional factors, like the hukou type or

the current trend of the Chinese labor market. Ngai

(2010) did a case study on female labor in Shenzhen,

China, showing that the hukou system created

deformed citizenship, which discouraged migrants

from moving, working, and truly integrating into

cities, finally causing them to work in an unstable

situation and to be precarious workers. Mrs. Dong is

one of the examples. However, we need to note that

she failed to quantitatively examine the relationship

between hukou and precarious employment. All in all,

according to the analysis above, due to the

institutional effects, people with agricultural hukou

often end up in the secondary labor market, the same

as precarious workers.

PMBDA 2022 - International Conference on Public Management and Big Data Analysis

198

In light of the research mentioned above, it can be

seen that there is a lot of literature exploring the

impact of the hukou system on the Chinese labor

market, especially on job discrimination, labor-

market segmentation, internal labor migration, labor

welfare policy, labor mental health, and labor

integration (Benach et al., 2000; Dulleck et al., 2012;

Fields & Song, 2020; Guo & Iredale, 2004; T. Liu et

al., 2022; Meng, 2012; Rönnblad et al., 2019; Song,

2014). However, precarious employment, exploding

recently and now representing a vital part of urban

employment, has not been quantitively carefully

studied in the context of the hukou system. Hence, as

a new but important aspect of the labor market, the

relationship between precarious employment and

hukou is worth further exploration and discovery

2.3 Hypothesis

From abundant existing studies of the hukou system

and dual labor market, it can be concluded that

precarious jobs, which are featured in low income,

lack of protection, and dangerous working situations,

most likely appear in the secondary labor market.

Coincidentally, people with agricultural hukou also

usually end up secondary market, so they are likely to

be employed precariously and unstably. Therefore, I

proposed the hypothesis below:

Hypothesis: People with agricultural hukou are

more likely to be in precarious employment than

people with non-agricultural hukou.

3 DATA AND MEASURES

3.1 Data

Data were collected from the Chinese General Social

Survey (CGSS), the first nationwide, comprehensive,

and continuous large-scale social survey program in

China. By collecting data from various aspects of

Chinese society systematically, CGSS aims to

summarize the trend of social change, promote the

openness of domestic social science research, and

provide data for government decision-making

(link:http://www.cnsda.org/index.php?r=projects/vie

w&id=94525591). This paper uses the 2017 wave

because it is the most recent database of CGSS, which

was released on October 10, 2020. There are 12,582

valid samples that were completed in CGSS 2017 in

total, and the data published online contains 783

variables.

This study imposed several restrictions on the

analytical sample. First of all, the research object is

limited to a population sample aged 16-60 years

(N=7441). Second, the paper drops the cases that do

not report dependent variables and key independent

variables such as education status, annual labor

income, and working years. Finally, 6372 samples

were obtained in this research.

3.2 Measures

The main dependent variable of this paper is

precarious employment, including two dimensions,

employment status, and part-time job status. Each

dimension would measure whether the sample

belongs to precarious employment or not

(Precarious=1, Not Precarious=0). Following Kong

(2010), this study extracts the two most important

features or dimensions of precarious workers, which

are employment status and part-time job status.

Employment status demonstrates one’s labor identity,

like whether he or she is self-employed or family

worker or another form of labor. Part-time job status

indicates the “precariousness” or “informality” of a

worker by examining whether this worker has one or

several jobs simultaneously.

Employment status. I use the question “Which of

the following situations is more suitable for your

current work status?” to measure precarious

employment. Following Liu and Zhong (2005),

precarious employment (coded=1) is classified as self-

employed labor (with fewer than seven employees),

temporary employment, dispatched labor, family

workers, or freelancers. If the respondents answered

none of those categories, they would be coded 0.

Part-time job status. The second dimension of

precarious employment is part-time job status, which

means that precarious employment is confirmed if

they participate in several part-time jobs (Part-time

Status=1). To measure part-time job status, the

research uses the question, “What is the nature of your

present job?” If the respondents answered that they

work full time, they would be considered non-

precarious employees (Part-time Status=0). Otherwise,

if the respondents answered they worked part-time,

they would be considered precarious employees (Part-

time Status=1).

Hukou.

The independent variable is the type of

household registration (Hukou status), which is

divided into agricultural household registration

(Hukou=1) and non-agricultural household

registration (Hukou=0). Referring to other scholars’

analysis of respondents’ household registration in

CGSS, this study decided to use the item “What is

your current household registration status” to

distinguish the type of the respondent’s hukou.

How Hukou Affects Precarious Employment: A Quantitative Analysis of the 2017 Chinese General Social Survey

199

Control variables include gender (male=1,

female=0), age, education level, annual labor income

(LnInc), marital status (married=1, not married=0),

working years, and the square of working years (Yang,

2012). These are commonly used variables to examine

human resources (Xie, 2012). The annual labor

income is measured by the question, “What was your

personal occupation/labor income last year (2016)?”

and I take the logarithm as the variable value to make

it more normally distributed. Instead of using monthly

income as the variable, the study can avoid data errors

due to the unsteady income of precarious workers.

Therefore, it is likely to examine the correlation

between variables more accurately. Besides, the

education level of respondents is measured by the

question, “What is your highest education degree?”

The respondents chose from “never received any

education=1, literacy class=2, primary school=3,

junior high school=4, vocational high school=5,

senior high school=6, technical secondary school=7,

technical school=8, junior college (Adult higher

education)=9, junior college (Formal higher

education)=10, Undergraduate (Adult higher

education)=11, Undergraduate (Formal higher

education)=12, Graduate and above=13.” This study

makes the assumption that the education level

increases in the order above.

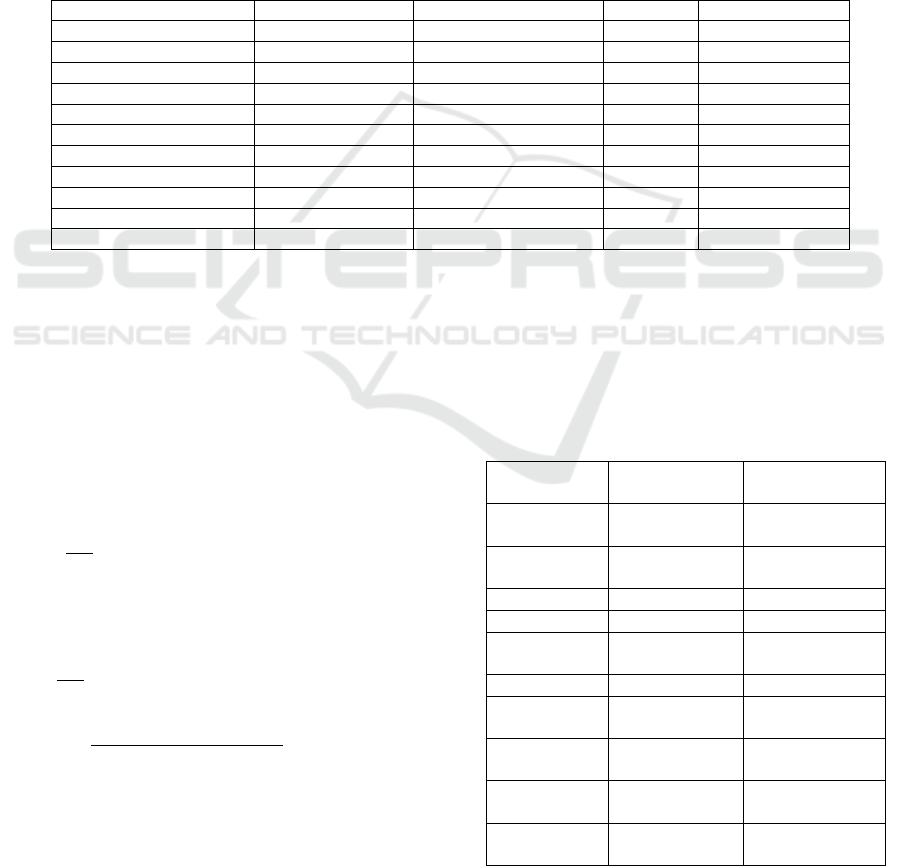

Table 1: Descriptive statistics.

Variables Mean Std.Dev. Min Max

Employment Status 0.26 0.438 0 1

Par

t

-time Status 0.10 0.296 0 1

Huko

u

0.65 0.477 0 1

Gende

r

0.47 0.499 0 1

Age 44.73 10.629 23 60

Annual Labor Income 46630.39 254513.127 0 9980000

LnInc 10.259 1.164 5.70 16.12

Education Level 6.04 3.391 1 13

Marital Status 0.94 0.246 0 1

Working Years 2.40 6.641 0 97

Working Years

2

49.87 215.035 0 9409

3.3 Analytical Strategy

The dependent variables, including employment

status and part-time job status, are binary categorical

variables (precarious=1, not precarious=0), and they

are influenced by k factors 𝑋

,𝑋

,𝑋

,…,𝑋

so the

binary logistic regression model was chosen to

explore the relationship between hukou type on

precarious employment. The model is presented

below:

𝐿𝑛

=𝛽

+𝛽

𝑋

+𝛽

𝑋

+⋯+𝛽

𝑋

(1)

In the model above, p represents the probability

of being precarious workers; 𝛽

,𝛽

,𝛽

,𝛽

represent

the regression coefficients. According to these, OR

(odds ratio) or exp(b) can be deduced:

=𝑒

⋯

(2)

Hence, the equation of p can be inferred:

𝑝=

⋯

⋯

(3)

By implementing the Hausman Test, the

significance is higher than 0.05, and the overall

accuracy of prediction in the crosstab is more than

70%, suggesting that the binary logistic regression

model fits very well.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Descriptive Analysis

Table 2: Descriptive Analysis between two different hukou

types.

Variables Agricultural

hukou

Non-agricultural

hukou

Employment

Status*

0.293 0.197

Part-time

Status*

0.116 0.062

Gende

r

0.463 0.477

Age* 43.88 45.19

Annual Labor

Income*

36207.23 65830.80

LnInc* 9.9565 10.7878

Education

Level*

4.82 8.29

Marital

Status

0.941 0.924

Working

Years*

2.11 2.94

Working

Years

2

*

37.48 72.93

*: p<0.05. t-test or chi-square test

PMBDA 2022 - International Conference on Public Management and Big Data Analysis

200

In this study, the hukou type was used as a

categorical variable to analyze other variables in a

crosstab. Because employment status, part-time job

status, gender, and marital status are categorical

variables, chi-square analysis was performed on them

in this study. According to the results of SPSS, the

significance of Pearson’s chi-square values of the

above four variables are 0.000, 0.000, 0.283, and

0.007, respectively. Hence, the marital status, part-

time status, and marital status were significantly

different between the two types of hukou (sig<0.05),

indicating that the two indexes of precarious

employment were significantly higher in the

agricultural hukou than in the non-agricultural hukou.

Besides, age, annual labor income, LnInc,

education level, working years, and the square of

working years are continuous variables, so they are

processed by t-tests to analyze the difference between

agricultural hukou and non-agricultural hukou. The

result shows that the significance of t-tests of those

six variables are all 0.000, indicating that they are all

significantly different in the two types of hukou.

Specifically, the age, annual labor income, education

level, working years, and the square of working years

in people with non-agricultural hukou are

significantly higher than in people with agricultural

hukou. Therefore, in light of the analysis above, the

indexes of precarious employment have a

significantly higher value in agricultural hukou

people, and the indexes of controlled variables

(human resources) are higher in non-agricultural

hukou.

4.2 Hukou And Employment Status

Then binary logistic regression model is used to

examine the hypothesis, controlling for gender, age,

LnInc, Education Level, Marital Status, Working

Years, and the square of Working Years. Results are

shown in Table 3.

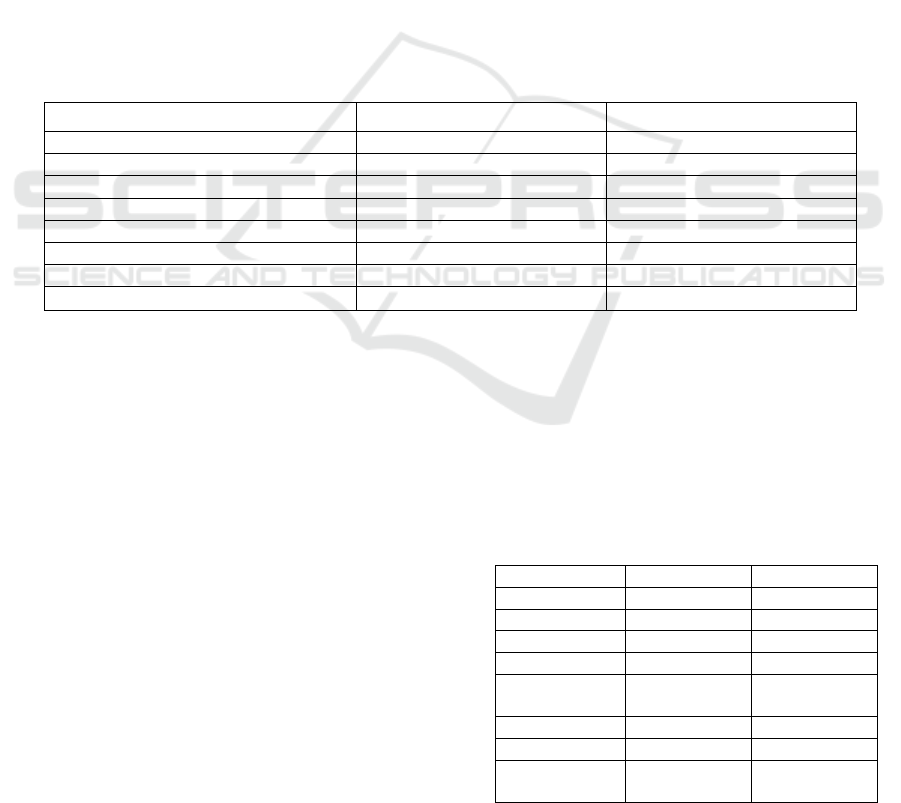

Table 3: Employment Status

Model1 Model2

Hukou (agriculture=1) 0.063*** 0.161*

Gender (male=1) 0.509***

Age -0.008*

LnInc -0.184***

Education Level -0.162***

Marital status -0.048

Working Years 0.094***

Working Years

2

-0.003***

Note:

*

p < 0.05;

**

p < 0.01;

***

p < 0.001

Model 1 of Table 3 is a simple model that

examines the association between hukou type and

employment status. It shows that the association

between hukou and precarious employment is

positive and significant (b=.063, p<.001). Model 2 of

Table 3 includes not only hukou but also other control

variables which may affect the result, such as Gender,

Age, LnInc, Education Level, Marital Status,

Working Years, and the square of Working Years.

Importantly, the regression coefficient of hukou is

0.161, and therefore, it can be calculated that the odds

ratio, exp(b), equals 1.175. That is, the probability of

being precarious workers in people with agricultural

hukou is 1.175 times higher than that in people with

non-agricultural hukou. The results confirm/support

H1.

Most control variables are in the expected

direction. To be specific, male workers and younger

workers are more likely to be precarious workers

(b=.509, p<.001; b=-.008, p<.05). Education level is

negatively associated with the likelihood of being

precarious workers (b=-.162, p<001). Working years

have a significantly positive relationship with the

probability of being precarious workers, whereas the

square of working years has a significantly negative

relationship with it (b=.094, p<.001; b=-003, p<.001).

4.3 Hukou and Part-Time Job Status

Table 4: Part-time Job Status

Model1 Model2

Hukou 0.680*** 0.267*

Gende

r

0.505***

Age -0.010

LnInc -0.237***

Education

Level

-0.092***

Marital status -0.087

Workin

g

Years 0.166***

Working

Years

2

-0.005***

Note:

*

p < 0.05;

**

p < 0.01;

***

p < 0.001

How Hukou Affects Precarious Employment: A Quantitative Analysis of the 2017 Chinese General Social Survey

201

Table 4 examines the effect of the type of household

registration on the part-time job status of precarious

workers. Model 1 includes only hukou, and Model 2

adds all the control variables. Most of the other

variables fit the expectation from Table 1. People who

are male and low-education are more likely to do

part-time jobs. Particularly, Gender has a

significantly positive relationship with Part-time

Status (b=.505, p<.001), and Education Level has a

significantly negative relationship with Part-time

Status (b=-.092, p<.001). Besides, similar to the

results in Table 3, the regression coefficient of

working years is positive, and the regression

coefficients of LnInc, education level, and the square

of working years are significantly negative. , But Age

and Marital Status do not have a significant

relationship with the independent variable, which is

not as same as a result in Table 2.

Table 4 shows that the type of Hukou has a

significantly positive relationship with the likelihood

of being precarious workers; that is, people who have

agricultural household registration are more likely to

have several part-time jobs in the labor market.

Model 2 in Table 4 also shows that after controlling

for these variables, there is a significant positive

correlation between hukou and the dependent

variable, proving this association is statistically

significant. Being calculated from the coefficient of

0.267, exp(b) or the odds ratio is 1.306. That is, the

probability of being precarious workers in people

with agricultural hukou is 1.306 times higher than

that of people with non-agricultural hukou. These

results also support/confirm H1.

5 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSION

Using the data of 6372 observations from CGSS 2017,

this study applies a binary logistic regression model

to analyze the impact of hukou type (type of

household registration) on precarious employment.

The findings show a significantly positive

relationship between precarious employment and

agricultural hukou. More specifically, people with

agricultural hukou are more likely to be precarious

workers; chances are also high that people who have

agricultural hukou would work part-time, having an

unstable working situation. The association holds

even controlling for gender, age, education, and

working years, suggesting an enduring impact of the

hukou barrier in the Chinese labor market.

There are some limitations that must be

considered in this study. First, this study adopts cross-

sectional data from 2017. Although this is the most

recent, publicly available survey, the situation of

precarious employment could be worse during the

current COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, if new

survey results are released, future studies can update

the database and pay more attention to the changes

that happened during the pandemic. Second, the

definition of precarious employment has other

dimensions that failed to be captured in this study due

to the limitation of the questionnaire of CGSS 2017.

Hence, other measurements, like contract status and

working situation, can be used in future studies in

order to have a better and more comprehensive

picture of precarious employment.

Some practical policy recommendations can be

drawn from this study. To begin with, noticing that

people with agricultural hukou are more possibly to

be precarious workers, the government needs to set

clear rules in the labor market to reduce

discrimination based on hukou status, which is the

same as employment discrimination based on gender.

However, the final source of this problem is the

unequal resources based on hukou status; that is,

people with agricultural hukou have fewer resources

than people with non-agricultural hukou, from

medical resources to educational resources, the most

important part of human resources. Therefore,

policies on employment, compulsory education, and

vocational training should be gradually decoupled

from the hukou status; instead, they should be based

on personal competitiveness.

REFERENCES

Benach, J., Benavides, F. G., Platt, S., Diez-Roux, A., &

Muntaner, C. (2000). The health-damaging potential of

new types of flexible employment: A challenge for

public health researchers. American Journal of Public

Health, 90(8), 1316–1317.

Benach, J., & Muntaner, C. (2007). Precarious employment

and health: Developing a research agenda. Journal of

Epidemiology & Community Health, 61(4), 276–277.

Brady, D., & Biegert, T. (2017). The Rise of Precarious

Employment in Germany. In A. L. Kalleberg & S. P.

Val la s (E ds .) , Precarious Work (Vol. 31, pp. 245–271).

Emerald Publishing Limited.

Burgess, J., & Campbell, I. (1998). The Nature and

Dimensions of Precarious Employment in Australia.

Labour & Industry: A Journal of the Social and

Economic Relations of Work, 8(3), 5–21.

Cranford, C. J., Vosko, L. F., & Zukewich, N. (2003).

Precarious Employment in the Canadian Labour

Market: A Statistical Portrait. Just Labour.

PMBDA 2022 - International Conference on Public Management and Big Data Analysis

202

Chen, Y, Zhang, Y. (2016). The unequal effect of

urbanization and social integration. Social Sciences in

China, 37(4), 117–135.

Dulleck, U., Fooken, J., & He, Y. (2012). Institutional and

individual labor market discrimination based on Hukou

status: An artefactual field experiment. In P. Lane, A.

Prat, & E. Sentana (Eds.), Proceedings of the 27th

Annual Congress of the European Economic

Association and 66th European Meeting of the

Econometric Society (pp. 1–48). European Economic

Association.

Ding, L. (2017). Study on influencing factors of pension

insurance participation willingness of flexible workers

[Master's thesis, Capital University of Economics and

Business].

Du, Q. (2020). Research on the choice of policy tools for

the protection of workers' Rights and interests in new

business forms. Chinese Public Administration, 09, 42–

48.

Fields, G., & Song, Y. (2020). Modeling migration barriers

in a two-sector framework: A welfare analysis of the

hukou reform in China. Economic Modelling, 84, 293–

301.

Gray, B., Grey, C., Hookway, A., Homolova, L., & Davies,

A. (2021). Differences in the impact of precarious

employment on health across population subgroups: A

scoping review. Perspectives in Public Health, 141(1),

37–49.

Gunn, V., Håkansta, C., Vignola, E., Matilla-Santander, N.,

Kreshpaj, B., Wegman, D. H., Hogstedt, C., Ahonen, E.

Q., Muntaner, C., Baron, S., Bodin, T., & The

Precarious Work Research (PWR) Group. (2021).

Initiatives addressing precarious employment and its

effects on workers’ health and well-being: A protocol

for a systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 195.

Guo, F., & Iredale, R. (2004). The Impact of Hukou Status

on Migrants’ Employment: Findings from the 1997

Beijing Migrant Census. International Migration

Review, 38(2), 709–731.

Guo, B. (2021). Study on Social Insurance Participation of

Gig Economy Employees [Master's thesis, Shanxi

University of Finance and Economics].

Kalleberg, A. L., & Vallas, S. P. (Eds.). (2018). Precarious

work (First edition). Emerald Publishing.

Knight, J., Song, L., & Huaibin, J. (1999). Chinese rural

migrants in urban enterprises: Three perspectives. The

Journal of Development Studies, 35(3), 73–104.

Kreshpaj, B., Orellana, C., Burström, B., Davis, L.,

Hemmingsson, T., Johansson, G., Kjellberg, K.,

Jonsson, J., Wegman, D. H., & Bodin, T. (2020). What

is precarious employment? A systematic review of

definitions and operationalizations from quantitative

and qualitative studies. Scandinavian Journal of Work,

Environment & Health, 46(3), 235–247.

Kong, L. (2010). A review on the social security of flexible

employment in China. Legal System and Society.

Liu, T., Liu, Q., & Jiang, D. (2022). The Influence of

Flexible Employment on Workers’ Wellbeing:

Evidence From Chinese General Social Survey.

Frontiers in Psychology, 13.

Liu, Z. (2005). Institution and inequality: The hukou system

in China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 33(1),

133–157.

Liu, G. (2022). Identification of employment status and

realization of social security rights and interests of

digital platform workers. International Economic

Review, 1–18.

Meng, X. (2012). Labor Market Outcomes and Reforms in

China. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(4), 75–

102. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.26.4.75

Ngai, P. (2010). Women workers and precarious

employment in Shenzhen Special Economic Zone,

China. Gender & Development.

Oddo, V. M., Zhuang, C. C., Andrea, S. B., Eisenberg-

Guyot, J., Peckham, T., Jacoby, D., & Hajat, A. (2021).

Changes in precarious employment in the United States:

A longitudinal analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Work,

Environment & Health, 47(3), 171–180.

Quinlan, M. (2012). The ‘Pre-Invention’ of Precarious

Employment: The Changing World of Work in Context.

The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 23(4), 3–

24.

Qi, Y., Ding, S., & Liu, C. (2022). Research on the

influence of Internet Use on wage income of flexible

workers in digital economy era. Social Science Journal,

01, 125-138+2.

Rönnblad, T., Grönholm, E., Jonsson, J., Koranyi, I.,

Orellana, C., Kreshpaj, B., Chen, L., Stockfelt, L., &

Bodin, T. (2019). Precarious employment and mental

health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of

longitudinal studies. Scandinavian Journal of Work,

Environment & Health, 45(5), 429–443.

Research group of Chinese Academy of Labor and Social

Security. (2005). Study on the Basic Problems of

Flexible Employment in China. Review of Economic

Research, 45, 2–16.

Song, Y. (2014). What should economists know about the

current Chinese hukou system? China Economic

Review, 29, 200–212.

Shao, L. (2022). Study on Tax Risks of flexible employment

model [Master's thesis, Yunnan University of Finance

and Economics].

Tompa, E., Scott-Marshall, H., Dolinschi, R., Trevithick, S.,

& Bhattacharyya, S. (2007). Precarious employment

experiences and their health consequences: Towards a

theoretical framework. Work, 28(3), 209–224.

Vosko, L. F. (2006). Precarious Employment:

Understanding Labour Market Insecurity in Canada.

McGill-Queen’s Press - MQUP.

Wu, X., & Zhang, Z. (2014). Hukou, occupational

segregation and Income inequality in urban China.

Social Sciences in China, 6, 118-140+208-209.

Wang, M. (2021). Review and selection of labor and social

insurance policies under the new business model.

Chinese Social Security Review, 5(03), 23–38.

Xie, G. (2012). Human Capital Return and social

integration of floating population in China. Social

Sciences in China, 4, 103-124+207.

Xu, L. (2004). Research on Labor market Segmentation in

China [Doctoral thesis, Jinan University].

How Hukou Affects Precarious Employment: A Quantitative Analysis of the 2017 Chinese General Social Survey

203

Yang, Y. (2012). Study on the Employment of floating

Population in China's urban Labor market

Segmentation [Doctoral thesis, Wuhan University].

Yueping, S., Hantao, W., Xiao-yuan, D., & Zhili, W. (2021).

To Return or Stay? The Gendered Impact of the

COVID-19 Pandemic on Migrant Workers in China.

Feminist Economics, 27(1–2), 236–253.

Zhang, Z. (2020). Flexible employment personnel to choose

to participate in the basic old-age insurance research

[Master's thesis, Shanghai University Of Engineering

Science].

Zhang, S. (2022). Economic Research on the protection of

labor Rights and Interests of new employment forms

[Doctoral thesis, Jilin University].

Zhao, Z. (2022). Flexible employment: A new mode of

employment that attracts much attention. China Human

Resources Security, 06, 30–31.

Zhang, Y., & Wang, H. (2011). Hukou Discrimination and

geographical Discrimination in urban labor market: A

study based on census data. Management World, 07,

42–51.

PMBDA 2022 - International Conference on Public Management and Big Data Analysis

204