IT-Structures and Algorithms for Quality Assurance in the

Medical Advisory Service Institutions in Germany.

Step 2: To err is Human. Consensus-Conferences

Vera Ries

1,*

, Klaus-Peter Thiele

1

, Bernhard van Treeck

2,†

, Sarah Schroeer

1

,

Christina Witt

1

and Reinhard Schuster

2

1

Medical Advisory Service Institution in North Rhine (MD Nordrhein), 40212 Duesseldorf, Germany

2

Medical Advisory Service Institution in Northern Germany (MD Nord), 23554 Luebeck, Germany

Keywords: Quality Assurance, Statutory Health Insurance, Medical Advisory Service Institution, Communication

Structures Between Different IT-Systems, Server Data Structures, Data Protection, Script Programming,

Client Office Answers Using Perl Modules, Integer Linear Programming, Consensus, Quality Benchmark,

Positive Criticism, Pseudonym-Protected Knowledge Transfer.

Abstract: 16 Regional Medical Advisory Service Institutions perform medical expertise assessments upon German

in- and out-patient care. Assessments have to accomplish a nationwide quality assurance plan with mandatory

public reporting. We developed strategies to resolve conflicting quality measurement evaluations in the same

item by different peers without unveiling the identity of the criticised medical expert or peer in the processes.

All workflows are completely digitalized using mathematical IT-based procedures for randomized sampling

and for an equal distribution of the medical expertise assessments to be reviewed. We even allow for smaller

sample sizes, so regional heterogeneity and the heterogeneity of the types of medical expertise assessment

pose a constraint satisfaction problem. We discuss models addressing this kind of problem type and present

possible solutions. Our technical framework for peer review distribution, data collection and final result

analysis includes a completely IT-based workflow not only masking the origin of the medical expertise

assessments discussed, but routing the peer review processes in a way that independent and impartial review

sheets are produced by peers that were previously not yet involved in the reviewing process. Finally, the

statistical distribution and outcomes of the review results are analysed.

1 INTRODUCTION

To err is human and occurs among medical experts as

well. Our aim is to establish a continuous mutual

learning situation within a benchmark framework for

a nationwide quality assurance plan covering all

medical expertise assessments performed by the

Medical Service Institution. We present a valuable

tool creating maximum transparency of outcomes but

founded on positive criticism without blaming

individual institutions or individual medical experts.

This quality initiative is unique in Europe by

creating nationwide outcome quality assurance

standards within the legal institutions that advise the

German health care insurance funds in declaring cost

*

https://md-nordrhein.de

†

https://md-nord.de

assumption for health care service. The health care

providers deserve that the legal institution appraising

quality benchmarks its own performance.

This innovative project was initiated in November

2016 by the head physicians' board of the 16 Regional

Medical Advisory Service Institutions (MD). In 2018,

a mutual agreement was reached regarding the quality

objectives, the criteria applied and the central IT

platform conception, its architecture and technical

workflow implementation (Ries et al., 2021). The

nationwide implementation started from November

2019 and will be accomplished by April 2023.

Meantime, the self-initiated nationwide quality

assurance became mandatory by a law amendment of

the German Social Code in December 2019 (Merkel

and Spahn, 2019).

Ries, V., Thiele, K., van Treeck, B., Schroeer, S., Witt, C. and Schuster, R.

IT-Structures and Algorithms for Quality Assurance in the Medical Advisory Service Institutions in Germany. Step 2: To err is Human. Consensus-Conferences.

DOI: 10.5220/0011632600003414

In Proceedings of the 16th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2023) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 271-278

ISBN: 978-989-758-631-6; ISSN: 2184-4305

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

271

2 LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 16 Regional Medical Advisory Service Institu-

tions performing medical health care expertise are

legally established by the German social legislation

(Gaertner and Gnatzy, 2011). A pre-existing peer

review based quality assurance system was mandated

by law in 2004, but restricted on long term care as-

sessments (Schmacke, 2016). The current nationwide

quality assurance plan's initiative started in 2016

(Ries et al., 2021) and was mandated by law ex post

in 2019 (Merkel and Spahn, 2019), adding a supple-

mentary advisory service institution.

2.1 Getting Started

In analogy to industrial quality standards for pro-

duction, quality is defined to measure the degree of

correspondence between the service provided by a

supplier and the service expected by the customer

(Masaaki, 1986; Gerlach, 2001; Kamiske and Brauer,

2011; Institute of Medicine, 1990 and 2001; Interna-

tionale Organisation fuer Normung, 2015).

The aim here was to review the kaleidoscope of

singular quality assurance measures regionally

performed and to merge it into one mutual commit-

ment based nation-wide quality perspective. Based on

this conception, a new quality assurance plan for

medical expertise assessments started in 2019, ad-

dressing the two main topics for medical expertise

assessments:

In-patient care:

hospital quality and billing control on behalf

of the health care insurance funds (Thiele et

al., 2018; Kreuzer et al., 2022);

Incapacity for work in out-patient care:

case management consultancy and medical ex-

pertise assessment in insurance questions aris-

ing in the area of incapacity for work service

(Nuechtern, 2008; Nuechtern und Mittelstaedt,

2015; Ries et al., 2022);

By choosing those two assessment topics, more

than 70 % of all medical expertise assessments were

covered within the pilot phase.

2.2 Rollout Schedule

By April 2024, the quality assurance plan covers all

medical expertise assessments performed on all

medical topics (Gostomzyk and Hollederer, 2022):

factual or putative medical treatment errors;

dental medicine / oral maxilla-facial surgery;

prevention and rehabilitation;

medical assistance supplies and prostheses;

plastic surgery, bariatric surgery, gender reas-

signment surgery;

psychotherapy, occupational therapy, speech

therapy, physiotherapy, intermittent home

nursing, palliative home care, hospice care;

new and unconventional diagnostic and thera-

peutic methods or medical devices, drug pre-

scription and drug treatment.

3 CHALLENGES

We had to solve challenging distributional problems.

3.1 Regional Heterogeneity

Germany is characterised by a huge regional and

sociodemographic heterogeneity of the 16 federal

states, leading to 20 % of the population agglomerate-

ing in North Rhine Westphalia, but five other institu-

tions in federal states representing less than 4 % of the

population, either due to their historically profiled

tiny regional size (Saar, Bremen) or to their rather

scarce population density (former Eastern Germany).

This creates institutional size variations from 100 to

up to 1.500 employees per regional institution.

3.2 Structural Heterogeneity

Our innovative workflow validates the internal quali-

ty assurance within the regional advisory service in-

stitutions in a double-check way by the external quali-

ty assurance of another advisory service institution,

creating a new and nationwide perspective.

Putting this challenging aim into reality was

further complicated by the heterogeneity of the IT-

systems. To tackle this problem, we implemented a

web-based portal that can be reached by any software

solution, processing data from different assessment

databases.

Conflicting regional legal regulations on data

protect-tion are posing a constant challenge for

cooperation on a nationwide level.

4 ACCOUNTING FOR INEQUITY

4.1 Adaption of Sample Size

The quantity structure of the nine topics of health care

benefits leads to more than 70 % of all assessments

performed in the single field of in-patient care, being

2.5 million medical expertise assessments per year.

HEALTHINF 2023 - 16th International Conference on Health Informatics

272

Figure 1: IT-architecture: Performing two quality reviews for a 10 % subset of the 0,5 % sample of all expertise assessments

performed by each of the 16 Medical Advisory Service Institutions.

A random sample of 0.5% is chosen for re-

gional quality assurance using peer reviews.

10 % of the previously chosen assessments are

randomly chosen for a double check peer re-

view by another regional institution genera-

ting the nationwide perspective.

This sampling leads to 12,500 regional peer reviews

and 1,250 nationwide peer reviews for in-patient care.

The remaining medical treatment topics generate

only a total of 650.000 assessments per year. For

reliability, we fixed minimal random sample sizes to

112 per year for regional quality assurance;

56 of the previously chosen assessments for a

double check peer review.

Since the peer review process is organized quarterly,

this provides every participant with a review by any

of the other participants in a quarterly rhythm,

validating internal quality assurance results.

4.2 Positive Criticism

Even this rigorous reduction was not yet feasible for

the five federal states representing less than 4 % of

the population, so we had to further reduced it to

56 per year for regional quality assurance and

28 randomly chosen for double check review.

From a psychologic point of view, it was

revealing that this concern was concealed by the

participants in the regular meetings of the quality

assurance working group, but proclaimed "out of the

blue" by the executive board.

This incident acted as an eye-opener to us. Quality

assurance management is a communication process,

first and foremost. Obviously, we had not yet

managed to create that situation of mutual trust and

learning within our working group that is crucial to

allow individual participants to raise word to focus on

important short-comings of the process.

Background analysis initiated by quality outcome

discussions reveal structural variations or even space

for clarifying procedural questions. Therefore, at least

one member of the corresponding medical expert

committee for the topic takes part in the consensus

conference, as well as at least one member of the head

physicians' board.

4.3 Pseudonym-Protected Knowledge

Transfer

Nobody wants to get passed on the red lantern, so it

is crucial to create an environment of positive

criticism and trustful mutual learning preventing the

participants of feeling embarrassed by raising

concerns or outing important short-comings (Beau-

champ and Childress 2001;

Varkey, B. 2021). A user-

friendly and trustful shaping of the quality assurance

IT-Structures and Algorithms for Quality Assurance in the Medical Advisory Service Institutions in Germany. Step 2: To err is Human.

Consensus-Conferences

273

communication process remains a constant quest

(Woodward, 2019). The nationwide quality assurance

plan conceals the identity of the peer reviewer and the

provenance of the medical expertise assessment.

Quality measurement and validation takes place

comparing all double-check review sheets, i. e.:

The internal review sheets: self-evaluation

review by an experienced peer within the

regional medical advisory service institution of

provenience.

The external review sheets: impartial

evaluation by an experienced peer belonging to

another regional medical advisory service

institutions.

5 IT PROCESSES FOR THE

CONSENSUS CONFERENCE

5.1 Structured Quality Review

The review sheets are composed of 20 core quality

criteria for all topics of health insurance benefits.

Several topics add specific quality criteria to check in

depth for medical accuracy in complex medical

assessment procedures like drug administration,

transsexualism or dental surgery.

Quality criteria ratings are colour-coded as

"adequate" green, "potential for improvement"

yellow and "inadequate" red. Synoptic review sheets

contrasting "green" with "red" in the same quality

criterion are eligible for a joint meeting of medical

experts designated by all regional institutions to

resolve conflicting views (consensus-conference).

Table 1: Validating internal quality assessment outcomes

by comparing with the outcomes by mutual peer review for

the same expertise assessments. In the topic shown above,

49 + 26 = 75 reviews are eligible for consensus.

5.2 Structured Peer Review

Communication

We consider the random sample of medical expertise

assessments from each of the nine topics for a period

of six months in three steps:

1. internal review by the author's peer (1° peer)

2. external review by a second peer, belonging

to another regional institution (2° peer),

3. possible modification of the internal

evaluation by the first peer in regard to the

external evaluation, creating the synoptic

review outcome sheet.

Figure 2: Peers gathering assessments to be treated in the

consensus-conference by discussing conflicting reviews via

the QA-Server.

5.3 Resolving Conflicting Reviews

To facilitate joint decision making, they are randomly

distributed into four groups with four parti-cipants

each. To guarantee objective judgements, no

participant can be involved in discussing reports ge-

nerated by himself (only third-party peers admitted).

Usually, we discuss 16 or 32 expertise assess-

ments per conference day. In order to solve the alloca-

tion problem, we start with a random order, followed

by group assignment to the first possible position in a

cyclic order. If there are no valid assignments left, we

search from top to bottom for possible replacements.

Opting for a few more candidate expertise assess-

ments to choose from, will facilitate the exchange

process. Other options are to change the initial

HEALTHINF 2023 - 16th International Conference on Health Informatics

274

random order of the expertise assessments or the

random group assignment of the institutions.

During the consensus conference, controversial

review sheets are processed by third party review. If

a common judgement within the third party peers

remains disputed, this expertise assessment will be

routed into the plenary discussion.

As soon as the third party groups have fixed their

group voting, persisting conflicting reviews are open

to discussion, leading to a final plenary voting in each

conflicting quality criterion, involving all 16 medical

experts. The final review results of the consensus-

conferences are stored as part of the public reporting.

Figure 3: IT implementation of the consensus process.

5.4 Logistic Framework

The red/green differences showed to be unevenly

distributed as well among the regional institutions as

across the quality criteria, so unveiling the prove-

nance of the reports and of the reviewer proved to be

of capital importance to maintain an objective, factual

and open exchange among the peers in order to revisit

critical process checkpoints in passing an expert

opinion, creating a common ground of agreement.

We usually started resolving the conflicting

reviews by establishing third party groups.

Alternatively, polarizing expertise reviews showing a

high load of red/green differences can be prepared for

individual live evaluation by every peer to discuss the

range of opinions openly during the consensus-

conference. To select the most polarizing reviews, we

performed a ranking by summing up the evaluation

differences between the internal and external review

(from green to red distance 2, otherwise 1). We advise

to check for the kind of assessment problem in order

to exclude reports addressing the same problem

repeatedly but in different criteria.

All previously described points are automatically

implemented via the QA-server, presenting to each

medical expert only those decisions he has to discuss

with his peers. If votes are necessary, they are carried

out live on the QA-server. Each peer sees the results

and the documented remarks in real time, which are

then transferred to the database to be available for

quality assessments reports.

6 PUBLIC REPORTING

The provident decision of the head physicians' board

in 2016 happened to gain the attention of the German

health politics. The Health Care Act in 2019 intro-

duced mandatory reports of the activities of the

regional Medical Advisory Service Institutions every

two years, including the nationwide quality assurance

plan's evaluation, starting in 2024.

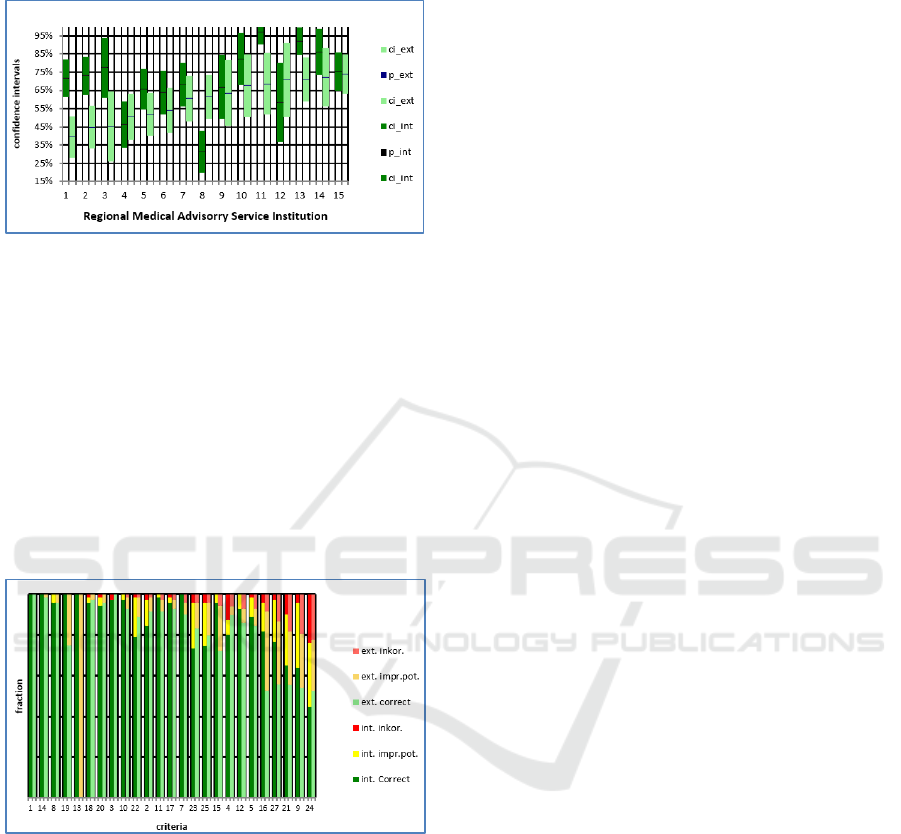

We will now present preliminary statistical results

for some paramount quality dimensions we analysed

so far. The following figures show the outcomes

concerning the medical assessment topic "incapacity

for work" displaying the first nine months in 2021.

6.1 Quality Dimensions

The quality assurance results were investigated

within several dimensions:

Cumulative internal quality assurance results

benchmarked against cumulative external

quality assurance results, using both a visuali-

sation as a bar plot and a secondary diagram

showing confidence intervals for differing

results.

Comparing the mutual peer review results on a

descriptive level in a table, indicating reliable

differences found by confidence values initiat-

ing quality improvement measures.

Focussing on quality outcomes within the own

institution for all criteria applied on all med-

ical topics addresses systematic weak points as

comprehensible language avoiding needless

IT-Structures and Algorithms for Quality Assurance in the Medical Advisory Service Institutions in Germany. Step 2: To err is Human.

Consensus-Conferences

275

technical terms, deploying medical facts and

recommendations in a well-structured way.

6.2 IT-Server Assisted Access

For training purposes, the expertise assessments are

shown in the QA-Server sorted by bad scores,

selecting for the highest number of criteria marked as

incorrect. Clicking on a cell on table 1 takes you

directly to a synoptic view of the internal and the

external reviews, provided both online and as file

export. A link to the original expertise assessment is

embedded in the synoptic review sheet, so all peers

can check for appropriate rating in every criterion.

All institutions can export the charts with the

individual results highlighted on a daily accurate

basis as a freely configurable graphic from the QA-

server, selected for quality criterion and for medical

assessment topic.

Figure 4: Individual quality assurance results of all regional

Institutions in one criterion for topic "incapacity for work".

6.3 Preliminary Quality Assurance

Results for Internal Peer Review

The benchmark of the cumulative internal results

shows varying results between the regional

institutions (MD), "MD 1" stating no incorrect

assessments and "MD 15" stating more than 40

percent of incorrect expertise assessments. The

criterion checks if all the medical information was

available. The divergent evaluation results judging

the same assessments highlights the need to reach a

uniform understanding of the quality standards,

initiated by the consensus conference discussions.

Each peer can see the position of his own

institution in the benchmark telling him whether he

acts particularly strictly or tolerantly (and possibly

inaccurate) as compared to the peers of the other

regional institutions. The other MD are concealed, the

number ID changing from chart to chart since the

position is sorted by growing amount of red ratings.

6.4 Benchmarking the Individual

Quality Assessment Results:

Outcome Validation by Mutual

Peer Review

Validation of individual internal quality assurance by

external review by a second peer focusses mainly on

the quality of the expertise assessments. The external

review is a representative mix of all other MDs over

a sufficiently long period of time. The left part of the

column graphic below always shows the internal

assessment and the right part the external review. In

"MD 9" the external evaluation is much more critical

than the internal. For "MD 15" the situation is

reversed.

Evaluation differences in a criterion spring to the

eye instantly, making analyses easy for the peers.

Additionally, confidence intervals are displayed:

In case the intervals are disjoint, there is a

statistically significant difference calling for action,

either inside the institution or even on a nationwide

level.

A critical reappraisal of the quality criteria

concerned will be proposed as subject for the

consensus conference discussion to discuss the need

for nationwide improvement measures.

Figure 5: Validation of quality assurance results by direct

comparison of the individual quality assurance vs. the

external mutual peer reviews for the same expertise

assessments (author peer vs. external second peer).

The confidence intervals of the external assessment in

Figure 6 are disjunct even in a horizontal perspective

for "MD 1" and "MD 15", additionally indicating a

significant difference in the quality of medical

expertise assessments between "MD 1" as compared

HEALTHINF 2023 - 16th International Conference on Health Informatics

276

to "MD 13", "MD 14" and MD15", an intriguing find-

ing of regional disparity.

Figure 6: Checking the variations found in a quality

criterion for statistically significant differences render

possible quality improvement measures.

6.5 Scope of Individual Improvement

It is of paramount importance for each regional

institution to gain this innovative perspective in order

to realise new improvement potential.

Quality assurance results vary a lot between the

criteria and are an ample monitoring tool to focus on

potentials for improvement in several topics, profiling

a general improvement measure like special trainings

for the medical experts authoring the assessments.

Figure 7: Specific charts for each individual regional

institution display all quality criteria within a medical

expertise assessment topic.

6.6 Future Prospects

The results of quality assurance will be published in

great detail in accordance with the recently adopted

statistics guideline. Thousands of real-time tables and

graphics are created by the QA-server processing

huge amount of data (Schuster, 2022).

Our next quality assurance tools to be developed are:

Time series including statistical significance

will monitor the effects of quality improve-

ment measures and possible confounders.

Monitoring the inter-rater-reliability within an

institution helps to identify internal evaluation

bias, benchmarking the nine medical

assessment topics against each other.

Analysing quality assurance outcome data

within a medical topic in regard to the nation-

wide inter-rater-reliability will enable us to

assess the process for differences in review

behaviour between the institutions involved as

a possible confounder.

7 CONCLUSIONS

The German health care insurance funds rely on

institutionalised medical experts to allocate the

appropriate health care service. The nationwide

quality assurance plan will empower the Medical

Advisory Service institutions to consolidate quality

performance on a nationwide level, strengthening the

legal task as an unimpeachable healthcare advisor.

We hope that this powerful tool will ease the

improvement processes, fostering a mindful dialogue

within the 16 Medical Advisory Institutions involved.

Consensus-conferences are meant to be a very

satisfactory and efficient quality assurance tool to

ascertain high quality in the peer review process.

REFERENCES

Altenstetter

, C., Busse, R. (2005). Health Care Reform in

Germany: Patch Change Within Established Governan-

ce Structures. J. Health Politics Policy Law, 30(1-2):

121–42.

Beauchamp, T.L., Childress, J.F. (2001)

Principles of Bio-

medical Ethics.

Oxford University Press.

Buehn,

S.,

Mathes,

T.,

Prengel,

P. ,

Wegewitz,

U.,

Ostermann,

T., Robens, S., Pieper, D. (2017). The risk of bias in

systematic reviews (ROBIS) tool showed fair reliability

and good construct validity to assess the risk of bias in

systematic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol., pages 121–128.

Cortina, J. (1993). What Is Coefficient Alpha? An Exami-

nation of Theory and Applications. J. Appl. Psychol., 78

(1):98–104.

Deming, W. E. (1982). Out of the crisis. Cambridge:

Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

DRV

(2018).

Qualitaetssicherung

der

sozialmedizinis

chen

Begutachtung. Manual zum Peer Review-Verfahren.

Berlin: Deutsche Rentenversicherung

Bund.

Eisinga, R., Grotenhuis, M., Pelzer, B. (2012). The relia-

bility of a two-item scale: Pearson, Cronbach or Spear-

man-Brown? Int J Public health, 58 (4): 637–642.

Gaertner, T., Gnatzy, W. (2011) Zum Sachverstaendigen-

status im Medizinischen Dienst der

Krankenversiche-

rung am Beispiel MDK Hessen. GuP 2011(5): 166-173.

IT-Structures and Algorithms for Quality Assurance in the Medical Advisory Service Institutions in Germany. Step 2: To err is Human.

Consensus-Conferences

277

Gerlach,

F.

M.

(2001).

Qualitaetsfoerderung

in

Praxis

und

Klinik:

eine

Chance

fuer

die

Medizin.

Stuttgart:

Thieme.

Gostomzyk, J. G., Hollederer, A. (2022) Angewandte So-

zialmedizin. Ecomed Medizin.

Institute of Medicine (2001). Crossing the Quality Chasm:

A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington,

DC, National Academy Press.

Institute of Medicine (1990). Medicare: A Strategy for

Quality Assurance. Volume II: Sources and Methods,

Washington, DC, National Academy Press.

Internationale

Organisation

fuer

Normung

(2015).

DIN EN

ISO

9001:2015-11.

Qualitaetsmanagementsysteme.

An-

forderungen. Beuth Verlag.

Kamiske, G. F. and Brauer, J.-P. (2011). Qualitaetsmanage-

ment

von

A

bis

Z

.

Carl Hanser Verlag.

Kreuzer, C., Thiele, K.-P., Ries V. (2022) Krankenhaus-

Abrechnungspruefungen und Qualitaetskontrollen. in:

Hartweg, H. R., Knieps, F, Agor, K (Eds.) Kranken-

kassen- und Pflegekassenmanagement. Springer Gab-

ler. Wiesbaden.

Machnik, W. (2009). 20 Jahre MDK Nordrhein. Ju

bilae-

umsschrift

.

MDK

Nordrhein.

Masaaki, I. (1986). Kaizen: The Key To Japan’s Competiti-

ve Success. McGraw-Hill Education.

Merkel, A., Spahn, J (2019) Gesetz fuer bessere und unab-

haengige Pruefungen (MDK-Reformgesetz) vom

14.12.2019. BGBl. I 2019 (51):2789-2816.

Newman, M. (2006). Finding community structure in net-

works using the eigenvectors of matrices. Physical

Review E, 74.

Normand, S.-L., Mcneil, B., Peterson, L., Palmer, R.

(1998). Eliciting expert opinion using the Delphi tech-

nique: identifying performance indicators for cardio-

vascular disease. IJQHC, 10:247-260.

Nuechtern,

E.

(2008).

Das

professionelle

Gutachten.

Beson-

derheiten in der gesetzlichen Krankenversicherung.

MedSach, 105 (3):96–98.

Nuechtern, E., von Mittelstaedt, G. (2015) Sozialmedizin:

Unabhaengig und fair in der Beurteilung. Dtsch Arztebl

112 (1-2): A-24 / B-20 / C-20.

Polak, U. W. (2018). Evaluation von Durchgangsarztbe-

richten mithilfe eines Peer-Review-Verfahrens. Trau-

ma Berufskrankh, 20 (Suppl. 4):237–240.

Ries, V., Thiele, K., Schuster, M. und Schuster, R. (2021)

IT-structures and Algorithms for Quality Assurance in

the Health Insurance Medical Advisory Service Institu-

tions in Germany. In: Biomedical Engineering Systems

and Technologies, pages 353-360. Springer Nature.

Ries V., Thiele, K.-P., Garbrock, K., Hassa, R. (2022)

Medizinische Dienste und Medizinischer Dienst Bund

in der Krankenversicherung. In: Hartweg, H. R.,

Knieps, F, Agor, K (Eds.) Krankenkassen- und Pflege-

kassenmanagement. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden.

Schuster, R. (2022) Strukturelle Beratung der Kranken-

kassen durch den Medizinischen Dienst in der Pharma-

kotherapie. Die Verwendung epidemiologischer und

gesundheitsoekonomischer Analysen im Zeitalter von

Digitalisierung und Big Data. In: Hartweg, H. R.,

Knieps, F, Agor, K (Eds.) Krankenkassen- und Pflege-

kassenmanagement. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden.

Sawicki, P., Bastian, H. (2008). German Health Care: A

Bit

of Bismarck Plus More Science. BMJ, 337:a1997.

Schmacke, N. (2016). Zur Positionierung des MDK in der

gesetzlichen Kranken- und Pflegeversicherung, Gutach-

ten im Auftrag des AOK-BV. In:

Bolte,

G.,

Goe

rres,

S.

Gerhardus,

A. (Eds.) IPP-Schriften

,

Uni

Bremen.

Shewhart, W. A. (1931). Statistical Method from the view-

point of quality control. (Reprint in1986 of a publication

of the

Department

of

Agricultuire

Mil

waukee 1931).

New York: Dover Publication.

Shinano, Y., Fujie, T., Kounoike, Y. (2003). Effectiveness of

Parallelizing the ILOG-CPLEX Mixed Integer Optimi-

zer in the PUBB2 Frame-work. In Euro-Par 2003 Paral-

lel Processing; 451-460. Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Strahl, A., Gerlich, C., Alpers, G., Ehrmann, K., Gehrke,

J.,

Mue

ller-Garnn,

A.,

Vogel,

H.

(2018).

Devel

opment and

evaluation of a standardized peer-training in the context

of peer review for quality assurance in work capacity

evaluation. BMC Medical Education, 18:135–145.

Strahl,

A.,

Gerlich,

C.,

Wolf,

H.-D.,

Gehrke,

J.,

Mue

ller-

Garnn,

A.,

Vogel,

H.

(2016).

Qualitaetssicherung

in der

Sozialmedizinischen Begutachtung durch Peer Review.

Pilotprojekt der DRV. Gesundheitswesen, 78:156–160.

Thiele, K.-P., Kreuzer, C., Mengel, R. (2018).

MDK-Prue-

fung: Fluch

oder

Segen?

In: Janssen, D., Augurz-ky, B.;

Krankenhauslandschaft in Deutschland: 89–94. Stutt-

gart: Kohlhammer.

Varkey B. (2021) Principles of Clinical Ethics and Their

Application to Practice. Med Princ Pract 2021, 30(1):

17-28.

Wirtz, M. and Caspar, F. (2002).

Beurteileru¨bereinstimmung

und

Beurteilerreliabilitaet:

Methoden

zur

Bestimmung

und

Verbesserung der

Zuverlaessigkeit

von

Einschae-

tzungen

mittels Kategoriensystemen

und

Ratingskalen

.

Goe

ttingen:

Hogrefe.

Woodward, S. (2019). Sign up for safety campaign. In: NHS

resolution. Being fair. resolution.nhs.uk.

HEALTHINF 2023 - 16th International Conference on Health Informatics

278