Human Factors for Cybersecurity Awareness in a Remote Work

Environment

César Vásquez Flores

1

, Jose Gonzalez

2

, Miranda Kajtazi

3

, Joseph Bugeja

4

and Bahtijar Vogel

4

1

Adesso Sweden, Malmö, Sweden

2

Accelerated Growth, Malmö, Sweden

3

Department of Informatics, Lund University, Lund, Sweden

4

Department of Computer Science and Media Technology, Internet of Things and People Research Center (IOTAP),

Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden

{joseph.bugeja, bahtijar.vogel }@mau.se

Keywords: Cybersecurity, Trust, Human Factors, Awareness, Employees, Remote Work Environment.

Abstract: The conveniences of remote work are various, but a surge in cyberthreats has heavily affected the optimal

processes of organizations. As a result, employees' cybersecurity awareness was jeopardized, prompting

organizations to require improvement of cybersecurity processes at all levels. This paper explores which

cybersecurity aspects are more relevant and/or relatable for remote working employees. A qualitative

approach via interviews is used to collect experiences and perspectives from employees in different

organizations. The results show that human factors, such as trust in cybersecurity infrastructure, previous

practices, training, security fatigue, and improvements with gamification, are core to supporting the success

of a cybersecurity program in a remote work environment.

1 INTRODUCTION

According to PurpleSec's 2021 Cybersecurity Trends

Report

1

, cybercrime has increased by 600% since the

start of the worldwide pandemic. Meanwhile, a study

by Splunk

2

found that 36% of IT executives reported

an increase in security vulnerabilities due to the shift

to remote work. In this environment, there is a greater

likelihood of financial losses and business

interruptions. The question of “what aspects of

cybersecurity are critical for organizations that must

conduct remote operations?” remains critical.

The human factor is commonly recognized as a

major vulnerability that can be exploited by

cyberattacks (D’Arcy et al., 2009). This is

exacerbated by a lack of training and knowledge

about cybersecurity, which can lead to an increase in

data breaches, non-compliance with security policies,

and intentional or unintentional violations by users,

particularly employees (Rubenstein & Francis, 2008;

Vance et al., 2013). As a result, various regulations

and frameworks, such as those of the National

1

https://gcnsolutions.com/blog/2021-cybersecurity-trends

2

https://purplesec.us/resources/cyber-security-statistics/

Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the

International Organization for Standardization and

the International Electrotechnical Commission

(ISO/IEC 27001), and the General Data Protection

Regulation (GDPR), recommend implementations

that contribute to improved data protection within

organizations (NIST, 2022; ISO/IEC 27001, 2022;

GDPR, 2022).

One key practice that these regulations and

frameworks have in common is that of fostering

cybersecurity awareness and training (Chowdhury et

al., 2022). This practice comprises the effective

transmission of policies and practices to all

organizational levels (Siponen & Vance, 2010). But

two reasons prevent the organizations from achieving

success in this endeavor. First, there is often a lack of

engagement of participants/employees (Chowdhury

et al., 2022); and second, organizations are not fully

prepared to ensure that cybersecurity programs are

regulated on how employees should participate and

perform (D’Arcy et al., 2009; Kajtazi et al., 2018).

Engagement is based on different factors such as

608

Flores, C., Gonzalez, J., Kajtazi, M., Bugeja, J. and Vogel, B.

Human Factors for Cybersecurity Awareness in a Remote Work Environment.

DOI: 10.5220/0011746000003405

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2023), pages 608-616

ISBN: 978-989-758-624-8; ISSN: 2184-4356

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

cultural, motivational, learning preferences, and other

behavioral-related theories that explain compliance

and noncompliance behavior in organizations

(Chowdhury et al., 2022; Bulgurcu et al., 2010).

Moreover, organizations tend to find it rather

challenging to cope with all the different factors that

drive human behavior in organizations (D’Arcy et al.,

2009; Sadok et al., 2020). Understanding the human

factor in cybersecurity is one of the most important

aspects of changing people’s behavior and their

awareness for remote working employees.

2 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

2.1 Cybersecurity and Remote Work

Remote work is described as organizational work that

is completed outside of the traditional organization's

physical location. Pranggono and Arabo (2021) stated

that in the UK, many organizations did not have a

procedure on how to build a remote workforce. The

authors also observed that only around 38% of

organizations had a security policy. Similarly, Naidoo

(2020) indicated that the most important priority for

organizations was to facilitate employees’ working

remotely in a short time. Consequently, the authors

emphasized that the organization did not have enough

time to build and deploy the correct security

safeguards.

Pranggono and Arabo (2021) stated that in a lot of

cases, employees used their home systems to perform

their jobs. These systems were secured by the

employer, but due to this new infrastructure, it created

a clear security concern. According to Alexander and

Jaffer (2021), existing safeguards such as the Virtual

Private Network (VPN) and other organizational

tools still contain vulnerabilities. The literature

suggests an inherent vulnerability in the current

remote work practices. In addition, there is a clear

increase in dependency on technology from

organizations (Naidoo, 2020), which has not been

overseen by cybercriminals, and the number of

cybercrimes has been observed to have grown

significantly. Naidoo (2020) also observed that

emotional factors can be an important factor in users’

compliance with security policies. It is important to

mention that these attacks are not necessarily new;

they have just been repeatedly exploited in this era.

Malware, including phishing or ransomware, DDoS,

and misinformation, for example, are among the most

commonly used cyberattacks during the COVID-19

era.

Furthermore, according to the Center for the

Protection of National Infrastructure (CPNI, 2020),

the complexity of remote work can be used to

generate insider threat attacks. This is because of

multiple factors: oversight from management, an

unfamiliar environment, stress, and poor screening

processes when adding new employees to the

organization.

The success of malware and phishing emails, for

example, resides in attackers using current relevant

information, in this case related to the pandemic, and

using it to attract users with their malicious software

(Naidoo, 2020). Furthermore, as observed by

Pranggono and Arabo (2021), DDoS attacks focused

on infrastructure and organizations that were

vulnerable or overwhelmed during the pandemic.

As an example of these organizations, Pranggono

and Arabo (2021) claimed that the internet or

healthcare providers were the targets. The reason for

this, according to their study, is that this type of

organization’s focus was set on other priorities than

cybersecurity, opening a window for vulnerability.

Ultimately, we see that users’ increased engagement

with technology left the door open for vulnerabilities

to be exploited by criminals.

As a result of this work environment change, it is

worthwhile considering aspects that go beyond

cybersecurity, which may affect its successful

implementation. Galanti et al. (2021) stated that

remote work presents some personal challenges for

users. First, family conflict that impacts work.

Second, social isolation, and third, the distracting

environment that users may be in. The importance of

this is that, as stated previously, emotional factors

may affect cybersecurity compliance on the part of

the users. In addition, envisioning a return to a

previous work environment and IT settings would not

be appropriate, but the new working conditions rather

give organizations an opportunity to explore different

options. Kane et al. (2021) observed that

organizations can take advantage of the effectiveness

of remote work. The authors suggested a hybrid

model that can provide the flexibility needed in a post

pandemic reality.

2.2 Employees’ Cybersecurity

Learning Process

Employees at all levels of an organization must be

aware of their responsibilities to protect the resources

they interact with. To implement a holistic

cybersecurity program, frameworks such as NIST

and ISO/IEC 27001 include the concepts of

awareness and training in their handbooks and guides

Human Factors for Cybersecurity Awareness in a Remote Work Environment

609

(NIST, 2022; ISO/IEC 27001, 2022). Awareness and

training are needed for any organization to secure

itself against cyberattacks. In this paper, we explain

these elements following the structure introduced by

Wilson and Hash (2003, p.8) who proposed the

learning continuum process, based on three

components: awareness, training, and education.

2.3 Cybersecurity Awareness

Awareness is the capacity of individuals to identify a

security concern and be able to respond adequately to

it when a risky event occurs (Wilson & Hash, 2003).

Previous investigations, books and reports in the

literature have defined in detail the concept and

mentioned aspects that could help to increase

awareness in organizations (Bada et al., 2015;

Stallings & Brown, 2018; Siponen, 2000). The

motivation of these studies was driven by different

objectives, such as the reduction of user-related

faults, the maximization of the efficiency of the

security procedures, and the compliance with

regulations (Siponen, 2000; Stallings & Brown,

2018).

Scholars in the field show that the intention to

provide people with information about existing risks

and recommended behaviors is one part of the

process, but not the entire process (Siponen, 2000;

Bada et al., 2015). In addition, the motivational aspect

is an important element considering that the final

objective of an awareness campaign is to modify the

employees’ behavior and attitudes (Siponen, 2000).

From an employee perspective, this requires different

steps, such as perceiving that the content is relevant,

then accepting how they should respond, and finally

being responsible to follow the advice despite the

existence of other demands (Bada et al., 2015). An

essential aspect is to design an awareness program

that “support the business needs of the organization

and be relevant to the organization’s culture and

information technology architecture” (Bowen et al.,

2006, p.31). One interesting observation obtained

from these studies is the influence of the motivational

factor in the success of awareness programs.

Moreover, an organization which will start the

implementation of awareness should conduct a needs

assessment to determine the status and justify the

allocation of resources for this endeavor (Wilson &

Hash, 2003). Because of this, different roles must be

involved. Some of them are organizational leaders,

whose role is critical in promoting full compliance;

security personnel, who are experts with extensive

knowledge of best practices and policies; system

users, who perform routine business operations; and

others (Wilson & Hash, 2003). The main challenge of

this approach is that a complete assessment of needs

often requires a hefty commitment from different

actors inside an organization. These actors must also

have certain roles, which are sometimes nonexistent

in some structures (Sadok et al., 2020). Additionally,

it could be interpreted that only the security personnel

are responsible for this task. However, managers need

to play a more effective role that is decisive (Soomro

et al., 2016). For that reason, some organizations

could be obligated to realize trade-offs or abbreviated

ways during the implementation which can lead to

lack of success.

Once the assessment is completed, the application

of the methods must be executed. Wilson and Hash

(2003) listed different tools and elements in their

wide-ranging study. In terms of content, topics such

as password management, email security, laptop

security while traveling, software license restriction

issues, and desktop security are possible options to be

included. The final decision to include one item or not

is based on a discussion that considers the

organizational context. Regarding the sources of

material, several themes could be combined or

introduced one at a time in each material, depending

on what skills need to be transmitted to the audience

(Wilson & Hash, 2003). For instance, e-mail

advisories, security websites, periodicals,

conferences, posters, flyers, courses, and seminars are

possible options to expose the information to the

employees (Wilson & Hash, 2003; Stallings &

Brown, 2018).

One positive aspect to also consider in the current

analysis of employee awareness is that today more

people are aware of security risks. Their constant

interaction with digital products motivates them to

proactively look for better personal protection

(Öğütçü et al., 2016). This could be a positive factor

for increasing the success of future awareness

programs.

Stallings and Brown (2018) highlighted that it is

relevant for organizations to share a security

awareness policy document with their employees.

This has three main objectives. First, to communicate

the requirement to employees to participate in the

awareness program on a mandatory basis. Second, to

inform that every employee will have enough time to

be part of the activities. Third, to clearly state who is

responsible for the management of awareness

activities.

While the positive aspects of awareness have been

constantly stated in previous publications, some of

them also analyzed the reasons that could potentially

prevent the success of cybersecurity awareness

ICISSP 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

610

endeavors (Bada et al., 2015). It is possible to see

cases of employees violating security policies even

though they have received some security preparation

(Kajtazi et al., 2018; Sadok et al., 2020). Kajtazi et al.

(2018) conducted an insightful study with more than

500 participants of two banks in Europe. The insights

showed that employees usually give more importance

to the completion of a work task than to a possible

exposition of confidential information (Kajtazi et al.,

2018).

This is supported by the idea that the immediate

benefit achieved with this specific task has a greater

priority than the avoidance of a future security cost.

(Kajtazi et al., 2018). Another relevant study

performed by Parsons et al. (2014) stated that

employers could feel confident that an improvement

in employees’ knowledge about security rules will

have a beneficial impact on their attitude. However,

the results helped to conclude that generic courses do

not influence the attitude as expected and therefore

training should be better contextualized (Parsons et

al., 2014).

2.4 Cybersecurity Training

Training is focused on teaching specific and

necessary security skills to employees depending on

the role they perform (Wilson & Hash, 2003). It is

relevant to state that the content of a training is

designed based on security basics and literacy

material, with tailored training based on the needs of

each group of people inside the organization (Wilson

& Hash, 2003; Bowen et al., 2006). For instance,

training must be different for a System Administrator

than for a Project Manager due to the different tasks

they realize, and the security knowledge required.

Additionally, recent papers have explained the

positive results obtained when employees’ learning

preferences are also considered in the design of

training (Chowdhury et al., 2022; Pattinson et al.,

2018).

Initially, a review of the various techniques used

to deliver training material is beneficial in

understanding the various options. Wilson and Hash

(2003) recommended that when opting for a

technology for training, aspects such as “ease of use,

scalability, accountability, and broad base of industry

support” must be evaluated (Wilson & Hash, 2003,

p.34). This is supported by the fact that organizations

are involved in an ever-changing environment where

the ability to adapt and expand their training with

continuous updates is perceived as a clear advantage.

Different techniques for implementing trainings

are classic, but also newly developed (Wilson and

Hash, 2003; Chowdhury et al., 2022; Pattinson et al.,

2018). Techniques such as interactive video training,

web-based training, computer-based training, onsite,

instructor-led training, and personalized training

allow for the incorporation of multiple techniques

into a single session as part of an organization's

cybersecurity program. With that in mind, Furnell et

al. (2002) conducted a study about a company which

implemented their own security training tool. One

aspect of this innovative tool was that information

about the suitability and the associated impact of each

security issue was shared with the participant (Furnell

et al., 2002). Also, they were able to see a message

explaining each possible decision they were able to

make with teaching purposes. This demonstrated a

good example of how different techniques could be

adapted and tailored to specific needs.

A relevant aspect of personalized training was

highlighted by Pattinson et al. (2018) who concluded

that the extent to which training is associated with the

participant’s learning preference is more important

than the frequency of the training. This could be a

strong reason to always consider personalized

training as one of the most effective options.

However, from a practical perspective, it would be

impossible to tailor the training based on each

individual characteristic. For that reason, a viable

option is to design different training based on certain

divisions inside the organization such as business

teams or groups (Pattinson et al., 2018).

Finally, it is important to note that nowadays, an

organization does not need to design exclusive

content for this endeavor, which is sometimes

complicated due to the probable absence of a specific

security area in the organization (Sadok et al., 2020).

Furnell et al. (2002) argued that, especially for small

organizations, this task is difficult to approach due to

a lack of expertise. On this note, Gartner (2021b)

published a report containing several options of

vendors offering computer-based training. Some

offer the option of a free knowledge check, and many

of them can be accessed as Software as Service

(SaaS) solutions.

3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This qualitative empirical study based on purposive

sampling had the following criteria for choosing

employees as respondents:

- Employees who use technology to perform their

daily jobs.

Human Factors for Cybersecurity Awareness in a Remote Work Environment

611

- Their organizations must have a cybersecurity

awareness and training program.

- Employees must have received cybersecurity

training before the pandemic.

- The organizations must have offered

cybersecurity training for remote working

employees.

- Their job routine has changed due to the

pandemic in terms of remote work.

- Participants must have relevant years of

experience.

In terms of business sectors, IT, Financial

Technology, and Business Process Outsourcing

(BPO) were taken into consideration, and also

regarded as information intensive organizations

(Kajtazi et al., 2018). These have been identified as

industries where cybersecurity implementation plays

an important factor. Further, the assumption is that

some behavioral theories could be perceived in a

different way by employees in different industries

(Bulgurcu et al., 2010).

The employees considered were identified in the

professional networks of the first two authors of this

paper. Once a participant confirmed the precondition

requirements, a brief explanation of the paper

objective was shared to ensure that they felt

comfortable and open to us.

The locations of our participants were Peru, the

USA, and Guatemala. A primary reason for choosing

such locations is that there was reportedly an increase

in the number of cyberattacks in those regions

(Statista, 2022). The requirement for participants to

have relevant years of experience led us to identify a

number of employees within senior roles that would

have a more mature perspective in terms of work

experience as well as could comprehend better the

pre- and during- pandemic cybersecurity efforts of

their organizations. Table 1 below shows relevant

information about the participants, such as the

organization, industry, role, country, and years of

industry experience.

Interviews were conducted remotely due to the

geographical location of participants. The first two

authors conducted one pilot interview (PR1), then

followed with five interviews (R1, R2, R3, R4, and

R5). While PR1 was useful to fine-tune the guide for

actual interviews, we retained the results of PR1 as

changes to the interview guide were not substantial

enough to re-direct the discussion in another way. In

fact, PR1 showed the robustness of our interview

guide.

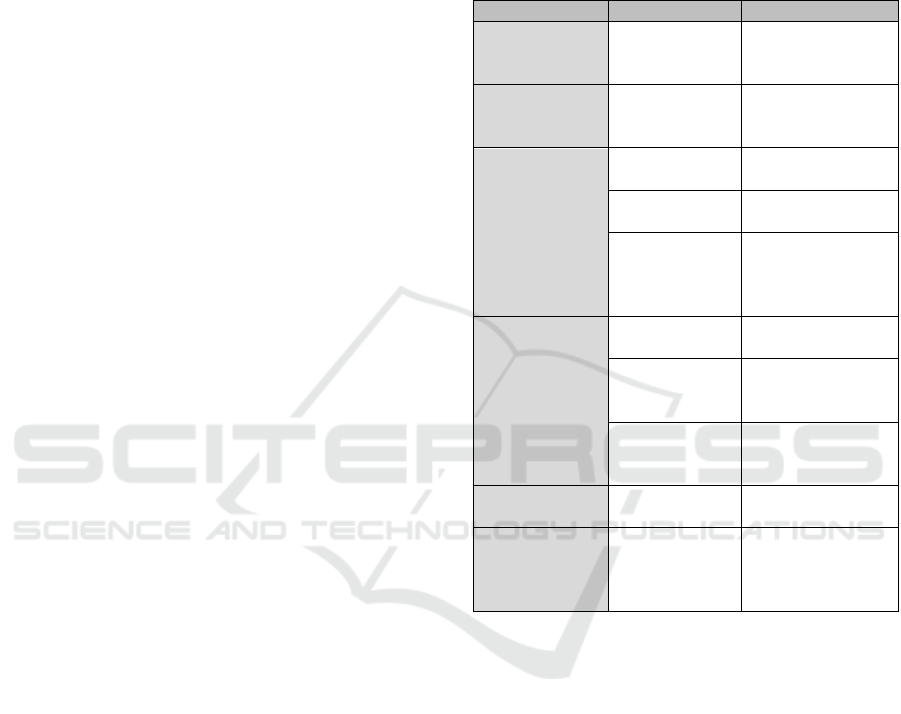

Table 1: Participant details.

No. Industry Role Country Experience Duration

PR1 IT

Software

Engineer

Peru 8 yrs 33 mins

R1

Financial

Technology

Risk

Manage

r

Guatemala 14 yrs 48 mins

R2 IT

Project

Manager

Peru 15 yrs 43 mins

R3 IT

Operations

Manager

Guatemala 13 yrs 37 mins

R4

Business

Process

Outsourcing

(BPO)

Program

Manager

USA 15 yrs 51 mins

R5 IT

Project

Manage

r

Guatemala 25 yrs 33 mins

The questions for the interview guide were based

on the themes identified and presented in the

conceptual framework (cf. Section 2), we present the

full version in Vasquez and Gonzalez (2022). In this

paper we categorized the data and findings based on

themes identified in the conceptual framework.

4 ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

COVID-19 brought a new work dynamic that led to

increased cybersecurity concerns. Based on our

results from the interviews, we can infer that the

majority of individuals in an organization today are

aware of the importance of cybersecurity with regard

to the human component, including its role, behavior,

and awareness aspects. We discuss details from our

results in the following sections by mapping their

relation to our conceptual framework and related

studies that influenced its composition.

4.1 Cybersecurity and Remote Work

Studies like that of Arabo (2021) have suggested that

many organizations do not have an established

procedure for having a remote workforce. However,

most of our interviewees stated that a practice of

working remotely was in place within their

organizations for specific employees. Further, the

same interviewees stated that there was a lack of

proper infrastructure or control in a remote work

environment which would then cast doubt on the

security practices the organizations had before the

pandemic. This important notice needs to be

addressed within the governance the company has for

ICISSP 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

612

such premature measures. In some organizations, the

inability to effectively scale-up and secure the already

in place practice of remote work needs to be improved

through governance measures. The literature has also

been vocal about the emotional factors within remote

work mixed with the pandemic and how they can

affect compliance with cybersecurity policies

(Naidoo, 2020). There are three factors we identified

through our interviewees. First, there is a lack of

bonding among team members. Second, there is

difficulty separating work from personal life due to

increased work hours. Third, there is difficulty

getting support for IT within the remote work context.

As a result, if security practices can be improved

along with increased employee support, the safety of

a hybrid work environment is possible; however, not

without focusing on such important cues that the

employees signaled.

4.2 Cyberthreats in a Remote Work

Environment

In terms of cyberthreats in the remote work

environment, an increase of attacks during the

pandemic (Naidoo, 2020) has been noticeable. This

supports our interviewees’ perceptions, who also

witnessed that the most common threat in their

remote work was phishing emails. In addition, even

when they were not categorized as insider threats by

our interviewees, all of them stated that employees

used company equipment and network for activities

unrelated to their job, a practice that continued

similarly in pre-pandemic times.

4.3 Cybersecurity Governance

Across all interviewees and their views on

cybersecurity governance, we saw a strong support of

the literature which states that one of the most

effective tools for managing the employee side of an

organization are policies, frameworks, and best

practices for technical and non-technical users (Guo

et al., 2021; NIST, 2022). Our respondents

demonstrated a general understanding of the policies

in place within their organization. One respondent

even shared a security framework they use, which

serves as further evidence of the effectiveness of

these methods for communicating cybersecurity

information and practices to employees.

4.4 Cybersecurity Training

The personalization aspect as a possibility to improve

training was an important point raised, which

promoted an interesting discussion during the

interviews. The interviewees were not only positive

about this aspect; they also acknowledged the fact

that personalized training could increase the sense of

identity of the employees. Such personalization could

also prevent overloading them with unnecessary

concepts in a training which can be performed based

on the access level of each employee. Recent studies

on personalization and training in the organizational

context have only been implemented by a few

organizations so far (Chowdhury et al., 2022;

Pattinson et al., 2018). The findings demonstrated a

good employees’ perception about personalization,

and yet there is little empirical research about its

implementation in organizations. For that reason, we

recommend ‘personalization aspect’ as a worthwhile

focus of study that might contribute to improving

training experiences in the future.

4.5 Employees’ Behavior

Our respondents confirmed that the behavior of some

employees is positively modified after the security

training. Specifically, they mentioned that they feel

engaged because they are aware of the possible risks

they can encounter (Bulgurcu et al., 2010). We

emphasize that our respondents have an accumulated

level of experience which may influence the

predisposition to modify their behavior. In terms of

deterrence and neutralization, scholars have stated

that if a sanction is clearly communicated by the

organization, an employee may be restrained from

realizing a security flaw (Straub & Wekle, 1998;

Willison & Warkentin, 2013). Even though, one of

the employees mentioned that there are legal

consequences for policy violation, the majority

referred to other reasons. In particular, a possible loss

of company prestige and a leak of customer

information were pointed out as causes. This could be

interpreted as a strong connection between the

employee and organizational assets. Therefore, the

deterrence effect is achieved through a more organic

way where sanctions are not the main reason to follow

the guidelines. The main conclusion obtained was

that the interviewees in a critical situation will avoid

breaking a cybersecurity policy. The interviewees

talked about re-evaluation, escalation, and

negotiation as first options before deciding not to

follow a cybersecurity policy. Furthermore, our

interviewees also confirmed that some employees

feel that this occurred through the description of some

events that they or their colleagues experienced. In

the first instance, none of them said directly that they

felt overwhelmed. However, they had an

Human Factors for Cybersecurity Awareness in a Remote Work Environment

613

understanding that the difficulties new employees

experience when they first see a cybersecurity policy

are not to be taken lightly. According to the literature,

more employees have a higher level of awareness and

general cybersecurity knowledge in today’s context

because their personal experience with technology

encourages them to learn more about the topic

(Öğütçü et al., 2016). According to our interviewees,

they all cover their work web camera, but not on their

personal devices. Furthermore, some organizations

have already implemented a physical restriction in the

devices to ensure that the camera is disabled by

default. This finding shows that awareness and risks

differ between individual practices on personal

devices with that of the organizational practices and

work-related devices.

4.6 Cybersecurity Program’s

Continuous Improvement

The main insight identified through our interviewees

is that gamification plays a central role. It is looked at

as a beneficial tool to increase the engagement of

employees in cybersecurity programs, especially if

many of them are young or in entry-level positions.

This finding is solid because one of the participants

confirmed to us that the actual implementation of

gamification in their company is indeed helping them.

Further research focused on the use of gamification

as a method to increase the success of a cybersecurity

program would be beneficial. Our respondents also

considered that, for improving a cybersecurity

program, the use of gamification is not only an option

but a solution. Gamification can enhance the user

experience of the process and motivate participants

based on possible rewards. It is appropriate

particularly for groups of employees, such as young

talent or those at entry-level positions who are

familiar with game techniques. Its inclusion in a

cybersecurity program could be a crucial factor.

4.7 Summary of Results

Our results are organized on the basis of identified

themes in our conceptual framework in Table 2. We

also highlight the identified aspects as relevant and/or

relatable by mapping the findings from our

interviewees. An aspect is considered relevant,

because it is a necessary condition to distinguish the

aspect when it is appropriate and contemporary to the

context of the employees, and/or relatable, when

there is a connection or engagement with a topic,

particularly from the employees’ perspective. Our

results also emphasize the importance of

understanding the human factor in cybersecurity.

Human factors have been researched extensively, but

our findings further underscore the importance of

prioritizing them for implementing effective

cybersecurity safeguards in the long run.

Table 2: Results from the interview study.

Theme Human facto

r

Consideration

Cybersecurity

and remote

wor

k

Emotional

factors

Relatable (R1, R4,

R5)

Cyberthreats in

a remote work

environment

Exposure to

cyberthreats

Relevant

(R2,R3,R4,R5)

Cybersecurity

governance

Previous

Practices

Relevant

(R2,R4,R5)

New employee

engagement

Relevant (R1,R4)

Trust in

cybersecurity

practices and

infrastructure

Relevant and

relatable

(R1,R2,R3,R4,R5)

Cybersecurity

training

Language Relatable (R2,

R4

)

Training

delivery

techni

q

ue

Relevant and

relatable (R1, R2,

R3, R4, R5

)

Content

according to

the role

Relatable (R1, R2,

R4, R5)

Employees’

b

ehavio

r

Security

Fati

g

ue

Relevant (R1, R2,

R4

)

Cybersecurity

program’s

continuous

improvement

Gamification Relevant and

relatable (R1, R2,

R4, R5)

5 CONCLUSIONS

This paper aimed to present core cybersecurity

awareness aspects that are particularly relevant and/or

relatable for remote working employees. We

presented a conceptual framework, which identified

that vulnerabilities in cybersecurity associated with

the remote work environment are numerous and

should not be neglected, but rather emphasized. We

categorized our results based on the identified themes

in our conceptual framework and mapped them to the

role of the human factor, their behavior, and

awareness aspects. We identified certain aspects as

relevant and/or relatable to the context of remote

employees. An aspect was considered relevant if it

was important and appropriate for the current

situation, and relatable if it connected or engaged the

employees with the topic from their perspective.

ICISSP 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

614

Some aspects were identified as both relevant and

relatable. In general, we found out that employees’

awareness plays a vital role in supporting the

cybersecurity strategy among organizations and that

there is a strong relationship between awareness and

training among the employees’ perspectives. The

result is not particularly different from previous

studies conducted pre-pandemic, but it is an

important finding to highlight that cybersecurity

measures from a training perspective are highlighted

as vital in forced remote working contexts. Likewise,

since remote working is a trend to be pursued by

various organizations in the long run, a focus on the

perspective of employees in terms of awareness

within this context is important.

One of the key conclusions of this research is that

emotional factors, trust in cybersecurity

infrastructure, previous practices, training, security

fatigue, and improvements with gamification are core

to supporting the success of a cybersecurity program

in a remote work environment. We also found out that

trust in cybersecurity practices and infrastructures is

becoming an important building block for remote

workers, especially when autonomous technology

becomes more prevalent. As such, trust and

trustworthiness in cybersecurity are aspects that we

aim to address in our future work.

REFERENCES

Alexander, K. B., & Jaffer, J. N. (2021). COVID-19 and the

Cyber Challenge. The Cyber Defense Review, 6(2), 17-

28.

Bada, M., Sasse, A. & Nurse, J. R. C. (2015). Cyber

Security Awareness Campaigns: Why Do They Fail to

Change Behavior? International Conference on Cyber

Security for Sustainable Society

Bowen, P., Hash, J. & Wilson, M. (2006). Information

Security Handbook: A Guide for Managers, NIST

Special Publication 800-100

Bulgurcu, B., Cavusoglu, H. & Benbasat, I. (2010).

Information Security Policy Compliance: An Empirical

Study of Rationality-Based Beliefs and Information

Security Awareness, MIS Quarterly.

Chowdhury, N., Katsikas, S. & Gkioulos, V. (2022).

Modelling Effective Cybersecurity Training

Frameworks: A Delphi Method-Based Study,

Computers and Security, vol. 113.

CPNI (2020) Personnel Security Guidance on Remote

Working – A Good Practice Guide

D’Arcy, J., Hovav, A. & Galletta, D. (2009). User

Awareness of Security Countermeasures and Its Impact

on Information Systems Misuse: A Deterrence

Approach, Information Systems Research, vol. 20, no.

1, pp.79–98.

Furnell, S. M., Gennatou, M. & Dowland, P. S. (2002). A

Prototype Tool for Information Security Awareness and

Training, Logistics Information Management, vol. 15,

no. 5/6, pp.352–357.

Galanti, T., Guidetti, G., Mazzei, E., Zappalà, S., &

Toscano, F. (2021). Work from home during the

COVID-19 outbreak: The impact on employees’

remote work productivity, engagement, and stress.

Journal of occupational and environmental medicine,

63(7), e426.

Gartner. (2021b). Security Awareness Computer-Based

Training Reviews and Ratings. Available online:

https://www.gartner.com/reviews/market/security-awa

reness-computer-based-training [Accessed 9 April

2022]

GDPR. (2022). General Data Protection Regulation,

Available online: https://gdpr-info.eu/ [Accessed 30

March 2022]

Guo, H., Wei, M., Huang, P., & Chekole, E. G. (2021).

Enhance Enterprise Security through Implementing

ISO/IEC 27001 Standard. In 2021 IEEE International

Conference on Service Operations and Logistics, and

Informatics (SOLI) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

ISO/IEC 27001. (2022). Information Security

Management, Available online: https://www.iso.org/

isoiec-27001-information-security.html [Accessed 30

March 2022]

Kajtazi, M., Cavusoglu, H., Benbasat, I. & Haftor, D.

(2018). Escalation of Commitment as an Antecedent to

Noncompliance with Information Security Policy,

Information and Computer Security, vol. 26, no. 2,

pp.171–193.

Kane G., Nanda, R., Phillips, A., Copulsky, J. (2021)

Redesigning the Post-Pandemic Workplace. MIT Sloan

Management Review.

Naidoo, R. (2020). A multi-level influence model of

COVID-19 themed cybercrime. European Journal of

Information Systems, 29(3), 306-321.

NIST. (2022). Cybersecurity Framework, Available online:

https://www.nist.gov/cyberframework [Accessed 28

March 2022]

Öğütçü, G., Testik, Ö. M. & Chouseinoglou, O. (2016).

Analysis of Personal Information Security Behavior

and Awareness, Computers and Security, vol. 56,

pp.83–93.

Parsons, K., McCormac, A., Butavicius, M., Pattinson, M.,

& Jerram, C. (2014). Determining Employee

Awareness Using the Human Aspects of Information

Security Questionnaire (HAIS-Q), Computers and

Security, vol. 42, pp.165–176

Pattinson, M., Butavicius, M., Ciccarello, B., Lillie, M.,

Parsons, K., Calic, D. & Mccormac, A. (2018).

Adapting Cyber-Security Training to Your Employees,

Proceedings of the Twelfth International Symposium

on Human Aspects of Information Security &

Assurance (HAISA 2018).

Pimple, K. D. (2002). Six domains of research ethics.

Science and engineering ethics, 8(2), 191-205.

Human Factors for Cybersecurity Awareness in a Remote Work Environment

615

Pranggono, B., & Arabo, A. (2021). COVID‐19 pandemic

cybersecurity issues. Internet Technology Letters, 4(2),

e247.

Pranggono, B., & Arabo, A. (2021). COVID‐19 pandemic

cybersecurity issues. Internet Technology Letters, 4(2),

e247.

Rubenstein, S., & Francis, T. (2008). Are your medical

records at risk? Wall Street Journal—Eastern Edition,

251(100), D1–D2

Sadok, M., Alter, S., & Bednar, P. (2020). It Is Not My Job:

Exploring the Disconnect between Corporate Security

Policies and Actual Security Practices in SMEs,

Information and Computer Security, vol. 28, no. 3,

pp.467–483.

Siponen, M. T. (2000). A conceptual foundation for

organizational information security awareness.

Information management & computer security.

Soomro, Z. A., Shah, M. H. & Ahmed, J. (2016).

Information Security Management Needs More

Holistic Approach: A Literature Review, International

Journal of Information Management, vol. 36, no. 2,

pp.215–225

Stallings, W., and Brown, L. (2018): Computer Security:

Principles and Practice. 4th Ed, Global Ed. Pearson

Education Limited, Harlow, United Kingdom

Statista (2020) Annual change in incidence of computer

viruses in Latin America and the Caribbean from

January to March 2020. Available online:

https://www.statista.com/statistics/1117225/computer-

virus-latin-america/ [Accessed 5 May 2022]

Straub, D. W., & Welke, R. J. (1998). Coping with Systems

Risk: Security Planning Models for Management

Decision Making, MIS Quarterly, vol. 22, no. 4,

pp.441–469

Vance, A., Lowry, P. B., & Eggett, D. (2013). Using

accountability to reduce access policy violations in

information systems. Journal of Management

Information Systems, 29(4), 263–290.

Vasquez, C., & Gonzalez, J. (2022). Cybersecurity

engagement in a remote work environment. Master’s

Thesis, Lund University.

Willison, R., & Warkentin, M. (2013). Beyond Deterrence:

An Expanded View of Employee Computer Abuse,

MIS Quarterly.

Wilson, M. & Hash, J. (2003). Building an Information

Technology Security Awareness and Training Program,

NIST Special Publication 800-50.

ICISSP 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

616