At School of Open Data: A Literature Review

Maria Angela Pellegrino

a

and Alessia Antelmi

b

Universit

`

a degli Studi di Salerno, via Giovanni Paolo II, 132 84084 Fisciano (SA), Italy

Keywords:

Review, Open Data, Workshop, School, Data Literacy, K-12 Learners.

Abstract:

Open Data are published to let interested stakeholders exploit data and create value out of them, but limited

technical skills are a crucial barrier. Learners are invited to develop data and information literacy according

to 21st-century skills and become aware of open data sources and what they can do with the data. They are

encouraged to learn how to analyse and exploit data, transform data into information by visualisation, and

effectively communicate data insights. This paper presents a systematic literature review of initiatives to let

K-12 learners familiarise themselves with Open Data. This review encompasses a total of 21 papers that met

the inclusion criteria organising them in taxonomies according to the used data format, the adopted approach,

and the expected learning outcome. The discussion compares the included initiative and points out challenges

that should be overcome to advance the dialogue around Open Data at school.

1 INTRODUCTION

According to the Data, Information, and Knowledge

pyramid, human beings build knowledge by exploit-

ing data and information (Frick

´

e, 2019). Data are the

facts from which information is derived, while infor-

mation provides meaning and context for data. Trans-

forming information into knowledge requires skills,

experience and insights gained through practice, re-

flection and social interaction (Piedra et al., 2017).

Recent studies have focused on the (re)use of data

with specific reference to the Open Data (OD) field

(Piedra et al., 2017), as it enables the opportunity to

freely adapt existing pieces of knowledge to create

personalised learning (Piedra et al., 2016), stimulate

critical thinking, collect relevant information and pro-

duce reliable conclusions (Tovar and Piedra, 2014),

and ensure learners’ readiness for the future job mar-

ket (Wolff et al., 2019).

OD can be freely used, re-used and redistributed

by anyone - subject only to the requirement to at-

tribute and share-alike (Open Knowledge Founda-

tion, 2013). The increasing OD availability may sup-

port innovation starting from citizens’ needs, but it

requires users to have appropriate skills to design

around large, complex data sets (Wolff et al., 2019).

Open allows to not just access, but use, modify, trans-

form and adapt data (Piedra et al., 2016).

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8927-5833

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6366-0546

OD behave as a valuable source to educate learn-

ers about the concept of data by providing factual

information, such as pollution, traffic, and popula-

tion conditions of their cities (Saddiqa et al., 2021).

Moreover, OD represent a tool to improve engage-

ment and scholarly learning (Piedra et al., 2017) and

raise curiosity about the data source, data availability

and the techniques underlying data access, extraction

and analysis (Trentini and Scaravati, 2020). By let-

ting learners interact with real OD within school sub-

jects, they would familiarise themselves with the con-

cept of data, understand what kinds of perspectives

OD may unlock and how they can be used (Susha

et al., 2015; Morelli et al., 2017), develop data liter-

acy (i.e., collecting, analysing, and interpreting data)

(Van Audenhove et al., 2020), and enhance digital

skills (Coughlan, 2020; Shamash et al., 2015) to be-

come critical thinkers (Watson, 2017; Ruijer et al.,

2020). Initiatives to teach data skills in school are of-

ten based on small data sets collected by the learners

themselves; nevertheless, these skills do not neces-

sarily scale when analysing larger and more complex

data sets (Wolff et al., 2019). OD are mainly used

by higher education students (Saddiqa et al., 2019a;

Anslow et al., 2016; Crusoe et al., 2019; Renuka

et al., 2017), while further effort should be invested in

equipping the younger generation with skills so they

can interact with data (Saddiqa et al., 2021).

This article presents a systematic literature re-

view of the effort invested by educators and experts

172

Pellegrino, M. and Antelmi, A.

At School of Open Data: A Literature Review.

DOI: 10.5220/0011747500003470

In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2023) - Volume 2, pages 172-183

ISBN: 978-989-758-641-5; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

in bringing underage learners close to OD. Learners

need hands-on experience with data collection to un-

derstand the concept of data and how to use OD (Sad-

diqa et al., 2021). For this reason, we focused on con-

tributions reporting on initiatives or structured work-

shops to let elementary and secondary school learners

familiarise themselves and exploit OD. This review

aims to:

• understand the current situation related to OD ini-

tiatives with learners up to 18 years old and pro-

vide an overview of the workshops’ settings;

• articulate reflections on future directions.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 de-

fines background and the terms used throughout the

paper. Section 3 describes the data collection process

for performing the literature review and clarifies the

inclusion criteria. Section 4 overviews the collected

articles. Section 5 thematically analyses and clusters

reflections regarding how to bring learners close to

OD. Section 6 concludes the article with final obser-

vations.

2 TERMINOLOGY AND

BACKGROUND

Data Format: Open Data and Linked Open Data.

“Open Data are data that can be freely used, shared

and built-on by anyone, anywhere, for any purpose”

(Open Knowledge Foundation, 2013). Tim Berners-

Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web, proposed a

5-star scheme for grading the quality of OD:

• 1 star - data are available on the Web, whatever

format, under an open license;

• 2 stars - data are available in a structured format,

such as Microsoft Excel file format (.xls);

• 3 stars - data are available in a non-proprietary

structured format, e.g., comma-separated values

(.csv);

• 4 stars - data follows World Wide Web Consor-

tium standards, like using RDF and URIs;

• 5 stars - all of the other, plus links to other Linked

Open Data (LOD) sources.

Hence, LOD are the best format to realise OD, where

data are structured as a graph and interlinked.

Formal, Informal and non-Formal Education.

According to the literature, education can be classi-

fied as formal, informal and non-formal (Dib, 1988).

• Formal Education: corresponds to a systematic,

organised education model, structured and admin-

istered according to a given set of laws and norms,

presenting a rather rigid curriculum as regards ob-

jectives, content and methodology. Hence, formal

learning is intentional, i.e., learning is the goal of

all the activities learners engage in. Schools are a

typical example of formal education.

• Non-Formal Learning: takes place outside for-

mal learning environments but in an organisa-

tional framework. It results from the intentional

learners’ decision and effort to master a particular

activity, skill or area of knowledge. Non-formal

learning typically occurs in community settings:

swimming classes, sports clubs, reading groups,

debating societies, amateur choirs and orchestras,

and associations.

• Informal Learning: takes place outside schools

and arises from the learner’s involvement in activ-

ities that are not undertaken with a learning pur-

pose in mind. Informal learning is involuntary

and an inescapable part of daily life. Informal

education comprises visiting museums, listening

to radio broadcasting or watching TV, or reading

books.

Data Literacy Competence Model. The Data Lit-

eracy Competence Model (DLCM) has been devel-

oped by the Flemish Knowledge Centre for Digital

and Media Literacy and comprises two major com-

petence clusters: using data and understanding data

(Seymoens et al., 2020). The competence clusters are

defined as follows:

• Using data, or the knowledge, skills and attitudes

to use data actively and creatively, namely:

– interpreting: read data, a chart, a table, and un-

derstand what they mean;

– navigating: autonomously extract the desired

message out of data;

– collecting: collect and organise raw data;

– presenting: present and visualise data.

• Understanding data, or the knowledge, skills

and attitudes to critically and consciously assess

the role of data, namely:

– observing: observe how data is communicated

and used;

– analysing: analyse the individual and social

consequences of the way in which data is com-

municated and used;

– evaluating: evaluate whether those conse-

quences are harmful or constructive;

At School of Open Data: A Literature Review

173

– reflecting: reflect on how the way in which data

are communicated and used should be adjusted

to minimise the harmful consequences.

Design Principles. According to (Wolff et al.,

2019), the design of activities for teaching data liter-

acy should follow a set of principles synthesised from

the existing principle found in the literature.

P

1

Inquiry Principle - The inquiry process has

the potential to scaffold data analysis. Learners

should be first lead in a guided inquiry to move

to an open inquiry when they achieve familiarity

with the data and the approach.

P

2

Expansion Principle - Workshops should start

from a representative snapshot of a small part of

the dataset and expand out, rather than starting

with the full, large data set and focusing in.

P

3

Context Principle - Use data from learners’ con-

text, either local to them or relating to them in

some way.

P

4

Foundational Competences Principle - Focus

on developing foundational competencies rather

than practical skills.

P

5

STEAM Principle - Take a STEAM approach by

working collaboratively on creative activities.

P

6

Personal Data Collection Principle - Learners

should work with data collected by themselves.

3 METHODOLOGY

This section clarifies the research questions (RQs),

the data collection process and the inclusion criteria

at the basis of the reported literature review.

Research Questions at the basis of this literature re-

view follow:

RQ1 - What is the current situation related to

make learners familiarise themselves with OD?

RQ2 - What should be considered in future OD

initiatives with learners?

Data Collection. The literature review was con-

ducted by in-depth reading, interpreting and cate-

gorising papers proposing initiatives and workshops

to let learners familiarise themselves with OD. The

aim was to develop a comprehensive understanding

and a critical assessment of the knowledge relevant to

this topic. This review considered studies involving

K-12 learners, i.e., scholars up to 18 years old.

This review focuses on contributions with an aca-

demic structure, published as peer-reviewed articles.

The Scopus database is one of the most comprehen-

sive database sources (Bakkalbasi et al., 2006), of-

fering the broadest documents coverage over other

databases (Mongeon and Paul-Hus, 2016), and in-

dexing the widest number of peer-reviewed litera-

ture sources (Mart

´

ın-Mart

´

ın et al., 2018) in Child-

Computer Interaction and Technology Enhanced

Learning. Hence, the Scopus database is selected in

this paper to review the current literature on initiatives

to disseminate the OD philosophy to K-12 learners.

Scopus includes interdisciplinary literature, across all

research fields, so the probability of missing key re-

search information is greatly reduced. However, the

performed procedure is fully detailed to make it pos-

sible to systematically repeat it on other databases.

We used OD, learners and different variations of

these terms as keywords. Specifically, we carried

out the following query: (TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“open

data” OR “open government data”) AND (child*

OR student* OR pupil* OR kid* OR scholar* OR

learner*)). We limited results to the Computer Sci-

ence, Engineering, and Social Sciences subject areas,

considering only English contributions published in

the last 10 years (2013–2022). A total of 709 papers

met these criteria.

Inclusion Criteria. We excluded all non-peer-

reviewed or not accessible papers as well as papers

with a topic not relevant for this review. For instance,

we left out papers presenting workshops held with

university students. To be included in this review, pa-

pers needed to overview and evaluate, if possible, ini-

tiatives and workshops to make learners author and

exploit OD. Considering these criteria, the number

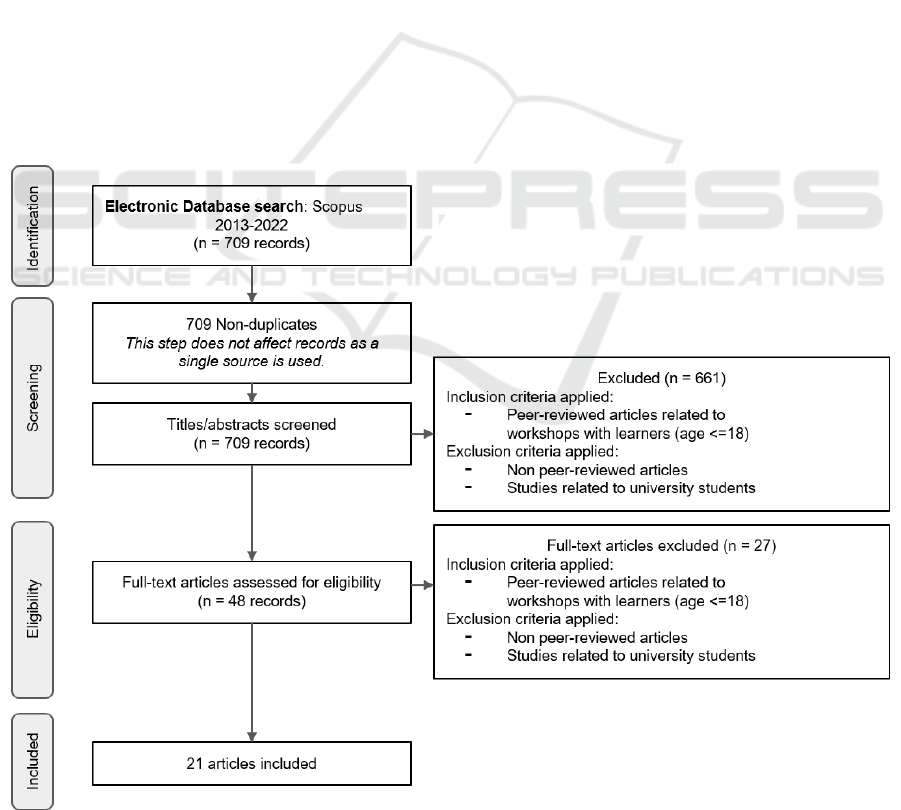

of selected papers was narrowed down to 21. Fig-

ure 1 summarises and schematically reports the ex-

clusion and inclusion criteria considered during the

selection process at the basis of this literature review.

It is worth noting that the same inclusion-exclusion

criteria are applied both in the abstract and in the full-

article revision. It can be justified by the lack of de-

tails reported in the abstract. It might happen that by

reading the abstract, an article successfully satisfied

inclusion-exclusion criteria, while reading details re-

ported in the article it did not.

4 OPEN DATA INITIATIVES

This section overviews OD educative initiatives and

workshops proposed in the literature to enable learn-

ers to familiarise themselves with OD (RQ1). Table 1

and Table 4 schematically summarise and compare

the main characteristics of each initiative. Specifi-

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

174

cally, Table 1 lists the data format, whether the learn-

ers implicitly or explicitly use the data, whether the

learners author new or exploit existing data, the ap-

proach adopted in delivering the activity, the learning

objective(s), and the target learners’ age. Table 4 fo-

cuses on the more structured workshops, describing

these activities in terms of setting, modality, duration,

the number of participants, and the design principles

covered by the workshop protocol. Table 3 reports

the skills covered by each OD initiative according to

the DLCM competencies. Two reviewers, first inde-

pendently and then discussing until the agreement, la-

belled the design principles and the DLCM competen-

cies covered by each initiative. In the following, we

briefly describe each initiative in chronological order.

Open Data Kit and Mobile Learning. (Chen et al.,

2014) employed an instructional pervasive gaming

model to deeper participants’ cultural heritage knowl-

edge. 43 10–11 years old learners were invited as par-

ticipants to explore individual and collaborative learn-

ing methods, learning effectiveness, attitude toward

mobile devices, and satisfaction with the gameplay.

DataPet, a Data Game for Children. (Dickinson

et al., 2015) proposed a participatory workshop last-

ing a single day, leading to the design of a digital pet

game by exploring OD and increasing community en-

gagement towards a better understanding of the air

quality of the surrounding environment. The study

involved 30 primary school learners (aged 10).

Data Literacy Projects in Canada. (Argast and

Zvyagintseva, 2016) describe a series of OD-focused

activities in collaboration with the Toronto Public Li-

brary, whose aim was to promote data literacy by pro-

viding participants with a fundamental understanding

of OD and assess how they could be used by citizens

and by the library system itself.

Data Murals. (Bhargava et al., 2016) describe a

Brazilian initiative whose aim was to build partici-

patory and impactful data literacy using a set of vi-

sual arts activities. Specifically, the activity involved

painting a mural to tell a story behind some official

government data of interest.

Translating OD to Educational Minigames. (Dun-

well et al., 2016) utilised the United States Depart-

ment of Agriculture’s OD on nutritional information

to implement four different mini-games to encourage

healthy lifestyles amongst adolescents.

Figure 1: PRISMA chart describing the workflow on the basis of this literature review.

At School of Open Data: A Literature Review

175

Table 1: Comparison of Open Data initiatives.

Reference

Data Implicit/ Authoring/

Approach Learning outcome Audience

format Explicit use Exploitation

(Chen et al., 2014) OD Implicit Authoring Game-based Culture learning via mobile-based

pervasive game and attitude towards

mobile devices

10-11

(Dickinson et al., 2015) OD Implicit Authoring Game-based Community engagement towards lo-

cal environment quality

10

(Argast and Zvyagintseva, 2016) OD Explicit Exploitation Workshop, hackathon Data literacy >12

(Bhargava et al., 2016) OD Explicit Exploitation Data stories/art Data literacy 16–21

(Dunwell et al., 2016) OD Implicit Exploitation Game-based Development of healthy lifestyles

amongst adolescents

14 – 16

(Basford et al., 2016) LOD Implicit Exploitation Gamified environment Awareness about Rhino conservation > 6

(Piedra et al., 2016) LOD Implicit Exploitation Blended learning Educational content consumption -

(Windhager et al., 2016) LOD Explicit Exploitation Visualisation-based Administration’s transparency and

public innovation

-

(Charvat et al., 2017) LOD Implicit Exploitation Game-based Environmental education 6–10, > 14

(

´

Alvarez Otero et al., 2018) OD Implicit Exploitation Game-based Environmental education and social

responsibility

12–16

(Ambrosino et al., 2018) OD Explicit Authoring Theory/Hands-on sessions Cultural heritage education 14–18

(Gasc

´

o-Hern

´

andez et al., 2018) OD Explicit Exploitation Theory sessions Development of OD-related skills 14–18

(Saddiqa et al., 2019c) OD Explicit Exploitation Theory/Hands-on sessions Data literacy 12–13

(Saddiqa et al., 2019b) OD Explicit Exploitation Theory/Hands-on sessions Data visualisation 13–14

(Wolff et al., 2019) OD Explicit Exploitation Pencil/Technology Data literacy 10–14

Escape the Buzz! (Seymoens et al.,

2020)

OD Implicit Exploitation Game-based Data privacy 10–18

Breaking the news! (Seymoens et al.,

2020)

OD Explicit Exploitation Data stories Data journalism 14–16

(Vargianniti and Karpouzis, 2020) OD Implicit Exploitation Game-based Data literacy and geographical educa-

tion

12

(Kurada et al., 2021) OD Explicit Exploitation Theory/Hands-on sessions Geo-spatial visualisations -

(Rubin, 2021) OD Explicit Exploitation Theory/Hands-on sessions Data literacy 12–15

(Saddiqa et al., 2021) OD Explicit Exploitation Theory/Hands-on sessions Data literacy 11–15

(Antelmi and Pellegrino, 2022) OD Explicit Exploitation Theory/Hands-on sessions Data literacy 14–18

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

176

Table 2: Summary of Open Data workshops. Legend: the symbol ✓means that the corresponding OD workshop fully supports

the principle, the symbol ∼ means that the corresponding OD workshop partially supports the principle, empty cell means

that the corresponding OD workshop not supports the principle, while the symbol - means that the principle is not applicable

to the corresponding OD workshop, for instance we do not consider P

2

compliant with authoring activities.

Reference Setting Modality Duration Participants P

1

P

2

P

3

P

4

P

5

P

6

(Chen et al., 2014) Formal

Two workshops

(In presence)

Hours 43 ✓ - ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

(Dickinson et al., 2015) Formal

Single workshop

(In presence)

One day 30 ✓ - ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

(Bhargava et al., 2016) Formal

(In presence)

Days 20 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

(Ambrosino et al., 2018) Formal

Single workshop

(In presence)

Hours 9 - ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

(Gasc

´

o-Hern

´

andez et al., 2018) Formal

(In presence)

6 months 6000 ✓ ✓ ✓

(Saddiqa et al., 2019c) Formal

Single workshop

(In presence)

1-1.5 hours 12 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

(Saddiqa et al., 2019b) Formal

Two workshops

(In presence)

2 days 21 ✓ ~ ✓ ✓ ✓

(Wolff et al., 2019) Formal

Four workshops

(In presence)

Few weeks each 67 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

Escape the DataBuzz!

(Seymoens et al., 2020)

Formal

Single workshop

(In presence)

50 mins 10 ✓ ✓

Breaking news!

(Seymoens et al., 2020)

Formal

Two workshops

(In presence)

50 mins each - ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

(Vargianniti and Karpouzis, 2020) Formal

Single workshop

(In presence)

Hours 43 ✓ ✓

(Vargianniti and Karpouzis, 2020) Non formal

Single workshop

(At a distance)

Hours 47 ✓ ✓

(Rubin, 2021) Non formal

Three workshops

(In presence)

10 hours each 24 ✓ ~ ✓ ✓ ✓

(Saddiqa et al., 2021) Formal

(In presence)

Hours 55 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

(Antelmi and Pellegrino, 2022) Formal

Six workshops

(At a distance)

2 hours each 73 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

Erica and Linked Open Data. Erica the Rhino (Bas-

ford et al., 2016) is an interactive art exhibit to raise

awareness of Rhino conservation. Thanks to the pres-

ence of sensors and actuators, the audience could in-

teract with Erica and learn about the live conditions

of the Rhino habitat (transparently queried to LOD

sources) via Erica’s behaviour.

LOD as Educational Material. (Piedra et al., 2016)

enhance face-to-face classrooms with the integration

of Open Educational Resources, creating a blended

learning environment, i.e., face-to-face learning inte-

grated with technology-based, digital instructions.

Linked Open Government Data Visualisation.

(Windhager et al., 2016) discuss methods and strate-

gies to increase citizens’ awareness related to the

availability and exploitation of open government data

to enhance the administration’s transparency and fos-

ter public innovation. The authors specifically focus

on the communicative power of data visualizations.

Geospatial Data in INSPIRE4Youth. IN-

SPIRE4Youth (Charvat et al., 2017) is an implemen-

tation of a European directive about the interoperable

exchange of spatial data and services. In particular,

the INSPIRE4Youth pilot project focuses on building

an Environmental and Geographical Web-based

atlas and educational quizzes based on the use of

Geospatial data, LOD and other environmental data

(maps) for educational and gaming purposes.

Geographical Open Data and Spanish Secondary

School Learners. (

´

Alvarez Otero et al., 2018) re-

port about the GI Learner project that trains secondary

school teachers and learners on Spanish National

Parks using OD on the cloud. The proposed method-

ology links Spanish OD with real-world places for a

better spatial understanding, environmental education

and social responsibility.

Open Data and Italian High-School Learners.

(Ambrosino et al., 2018) focused on the protec-

tion and preservation of the cultural heritage in the

Campania region by engaging local communities via

OD, including a community of learners within the

“School-to-work transition” program, an educational

path designed to prepare learners to enter the job mar-

ket.

Open Government Data (OGD) and OpenCoe-

sione. From 2014 to 2017, thousands of sec-

At School of Open Data: A Literature Review

177

Table 3: Skills covered by OD initiatives. Legend: I - inter-

preting, N - navigating, C - collecting, P - presenting, O -

observing, A - analysing, E - evaluating, R - reflecting.

Reference

Using Understanding

I N C P O A E R

(Chen et al.,

2014)

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 4

(Dickinson

et al., 2015)

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 5

(Argast and

Zvyagint-

seva, 2016)

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 5

(Bhargava

et al., 2016)

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 4

(Dunwell

et al., 2016)

✓ ✓ 2

(Basford

et al., 2016)

✓ ✓ ✓ 3

(Piedra et al.,

2016)

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 4

(Windhager

et al., 2016)

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 5

(Charvat

et al., 2017)

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 4

(

´

Alvarez

Otero et al.,

2018)

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 7

(Ambrosino

et al., 2018)

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 8

(Gasc

´

o-

Hern

´

andez

et al., 2018)

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 8

(Saddiqa

et al., 2019c)

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 8

(Saddiqa

et al., 2019b)

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 7

(Wolff et al.,

2019)

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 4

Escape the

DataBuzz!

(Seymoens

et al., 2020)

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 5

Breaking

news! (Sey-

moens et al.,

2020)

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 8

(Vargianniti

and Kar-

pouzis,

2020)

✓ ✓ 2

(Kurada

et al., 2021)

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 7

(Rubin,

2021)

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 7

(Saddiqa

et al., 2021)

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 6

(Antelmi and

Pellegrino,

2022)

✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ 8

22 initiatives 17 17 15 16 17 16 14 9

ondary students from more than 400 schools across

Italy participated in the project “OpenCoesione

School”(Gasc

´

o-Hern

´

andez et al., 2018). This initia-

tive’s main goals were to engage the public in using

data from the Italian OD portal OpenCoesione.gov.it

to monitor public spending from European Union’s

funds and to engage high-school learners in a six-

month course focused on OGD and data journalism.

Open Data in Danish Schools. (Saddiqa et al.,

2019c) investigated the possible impact of OD in

Danish schools under the framework of the Commu-

nity Driven research project, whose main focus was

understanding how young people can be educated to

foster participation in the city’s development using

open and sensor data.

Open Data Visualisation in Danish Schools. In an-

other work, (Saddiqa et al., 2019b) specifically fo-

cused on the importance and challenges of introduc-

ing OD visualisations in educational aspects by ex-

ploiting the real information of pupils’ school areas.

Open Data in English Primary and Secondary

Schools. The Urban Data School study (Wolff et al.,

2019) proposed a method for making 10—14 years

old learners familiarise themselves with complex data

collected through a smart city project, develop liter-

acy skills with real OD, and support them in asking

valid questions from data guided by interactive data

visualisations.

The DataBuzz Project. (Seymoens et al., 2020) de-

scribe a large-scale data literacy initiative carried out

with DataBuzz, a high-tech, mobile educational lab

housed in a 13-meter electric bus. The project’s goal

was to increase the data literacy of different segments

of society in the Brussels region through inclusive and

participatory games and workshops.

Open Data for an Educational Game. (Vargian-

niti and Karpouzis, 2020) used Wikidata to create

Geopoly, a Monopoly-based board/digital game. 90

12 years old learners joined the activity, 43 playing

with the physical Geopoly and 47 playing the digi-

tal version at home (due to COVID-19 quarantine).

The main goal of this activity was to offer an edu-

cational environment to improve students’ familiarity

with concepts and relations in the data and, in the pro-

cess, their learning performance in geography.

Geospatial Visualization on Real-Time Data. (Ku-

rada et al., 2021) propose a methodology for visualis-

ing real-time geospatial data extracted from an Indian

OGD platform. The methodology comprehends data

collection, data preprocessing, and data analysis to

apply machine learning, model building, and the au-

thoring of communicative results. The proposed ap-

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

178

Table 4: Summary of Open Data workshops. Legend: the symbol ✓means that the corresponding OD workshop fully supports

the principle, the symbol ∼ means that the corresponding OD workshop partially supports the principle, empty cell means

that the corresponding OD workshop not supports the principle, while the symbol - means that the principle is not applicable

to the corresponding OD workshop, for instance we do not consider P

2

compliant with authoring activities.

Reference Setting Modality Duration Participants P

1

P

2

P

3

P

4

P

5

P

6

(Chen et al., 2014) Formal

Two workshops

(In presence)

Hours 43 ✓ - ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

(Dickinson et al., 2015) Formal

Single workshop

(In presence)

One day 30 ✓ - ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

(Bhargava et al., 2016) Formal

(In presence)

Days 20 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

(Ambrosino et al., 2018) Formal

Single workshop

(In presence)

Hours 9 - ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

(Gasc

´

o-Hern

´

andez et al., 2018) Formal

(In presence)

6 months 6000 ✓ ✓ ✓

(Saddiqa et al., 2019c) Formal

Single workshop

(In presence)

1-1.5 hours 12 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

(Saddiqa et al., 2019b) Formal

Two workshops

(In presence)

2 days 21 ✓ ~ ✓ ✓ ✓

(Wolff et al., 2019) Formal

Four workshops

(In presence)

Few weeks each 67 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

Escape the DataBuzz!

(Seymoens et al., 2020)

Formal

Single workshop

(In presence)

50 mins 10 ✓ ✓

Breaking news!

(Seymoens et al., 2020)

Formal

Two workshops

(In presence)

50 mins each - ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

(Vargianniti and Karpouzis, 2020) Formal

Single workshop

(In presence)

Hours 43 ✓ ✓

(Vargianniti and Karpouzis, 2020) Non formal

Single workshop

(At a distance)

Hours 47 ✓ ✓

(Rubin, 2021) Non formal

Three workshops

(In presence)

10 hours each 24 ✓ ~ ✓ ✓ ✓

(Saddiqa et al., 2021) Formal

(In presence)

Hours 55 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

(Antelmi and Pellegrino, 2022) Formal

Six workshops

(At a distance)

2 hours each 73 ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

proach is conceived as a guidebook for novice learn-

ers to master data visualisations.

The Data Clubs Project.

1

(Rubin, 2021) introduces

pupils aged 12–15 to the importance of data using

the CODAP

2

platform, a free web-based platform to

easily explore and visualise data in summer or after-

school activities. Specifically, the project is articu-

lated over three modules, each focused on a specific

topic lasting 10 hours.

Open Data in Danish Secondary Schools. (Saddiqa

et al., 2021) investigated how OD can be used to de-

velop data literacy skills with secondary school stu-

dents (ages 11—15). Using qualitative and quantita-

tive research methods, they identified how data col-

lection and analysis could be integrated into school

education using openly available data sets focusing

on data skills that can be enhanced using OD.

OGD and Italian High-School Learners. (Antelmi

and Pellegrino, 2022) ran a series of workshops with

73 Italian high school learners specialising in classical

studies from 14 to 18 years old. Workshops took place

online due to COVID-19 regulations, and in a formal

setting, from February to May 2022. They spanned

1

The Data Clubs project: https://www.terc.edu/

dataclubs

2

The CODAP platform: https://codap.concord.org

over five days for each class, two hours per day, one-

hour introductory phase and one-hour hands-on ses-

sion. During the introductory phase, the moderator

explained concepts related to sources of OD, data vi-

sualisation and communication.

5 REFLECTIONS AND

DISCUSSIONS

This section summarises discussions concerning OD

initiatives by thematically analysing and clustering re-

flections. Each discussed aspect points out widely

adopted practices in the overviewed initiatives and

challenges that should still be addressed in the future

(RQ2).

Learners Rarely Author OD. As visible in Table

1, OD initiatives mainly focus on OD exploitation,

and they rarely move learners to the position of OD

producers. Consequently, learners do not usually ex-

perience OD production challenges, such as defining

data schema, collecting information, dealing with li-

censes, and mastering OD authoring tools. Only in

3 out of 22 initiatives, learners author OD and only

(Ambrosino et al., 2018) let them do it explicitly,

while (Chen et al., 2014) and (Dickinson et al., 2015)

mask OD collection by a game-based approach.

At School of Open Data: A Literature Review

179

OD Initiatives Learning Approaches. The most

common approaches used to move OD closer to learn-

ers are theory/hands-on sessions and game-based ap-

proaches (see column Approach in Table 1). Data

literacy is experienced via theory/hands-on sessions

in (Rubin, 2021; Saddiqa et al., 2021; Antelmi and

Pellegrino, 2022) and by game-based approaches in

(Wolff et al., 2019; Vargianniti and Karpouzis, 2020).

The same consideration is applicable to culture and

geography learning that is experienced by game-

based approaches in (Chen et al., 2014;

´

Alvarez Otero

et al., 2018; Vargianniti and Karpouzis, 2020) and via

theory/hands-on sessions in (Ambrosino et al., 2018).

Usually, the approach to delivering the activity is in-

dependent of the learning outcome.

The most original approach to learning data liter-

acy (Bhargava et al., 2016) and data journalism (Sey-

moens et al., 2020) is to author data stories. Journal-

ists and media curators widely adopt data stories via

Tableau-Stories (Akhtar et al., 2020), iStory (Beheshti

et al., 2020), and Gravity (Obie et al., 2020). The

story-based approach is also recognised as a promis-

ing approach in educational settings (Addone et al.,

2021) and lets learners master data visualisation, learn

how to use data to support discussions, and commu-

nicate data insight effectively.

As a general trend, there is no clear distinction

between approaches targeting specific ages. When

dealing with a younger audience (minimum six years

old), unplugged (such as pencils used in (Wolff et al.,

2019)) and game-based approaches are the most com-

monly used. Nevertheless, authoring data stories re-

quire data literacy and data visualisation skills, com-

pliant with a mature audience.

Lack of a Standard Setup. There is no standard

setup to deal with OD structured initiative, as shown

in Table 4. Workshops differ in duration, settings, and

modality. Moreover, the performed steps are scarcely

described; thus, making it difficult to reproduce them

and achieve a fair comparison. As a general attitude,

OD initiatives mainly focus on bringing participants

closer to the philosophy of OD without introducing

extra challenges posed by more advanced data pub-

lishing mechanisms, such as LOD and Semantic Web

technologies. As can be noticed from the column

Data format in Table 1, only 4 out of 22 initiatives

deal with LOD, which are only implicitly exploited.

However, LOD have the potential to provide effec-

tive educational resources (Donato et al., 2020; Piedra

et al., 2016); hence, OD initiatives should further in-

vestigate how to move learners close to LOD.

OD Workshops as In-Person Meetings. Most of

the overviewed workshops took place in person, prob-

ably to easily fulfil P

5

and let participants work col-

laboratively (Wolff et al., 2019). However, further ef-

fort should be invested in letting OD initiatives sur-

vive when a remote modality is strictly required, as

during the COVID-19 pandemic (Vargianniti and Kar-

pouzis, 2020). Online courses accommodate learn-

ers by offering them the flexibility to attend for-

mal learning when and where is more convenient for

them (Piedra et al., 2016). Nevertheless, it requires

dealing with common challenges in motivating learn-

ers to complete the out-of-class activities and join the

online discussions (Piedra et al., 2016; Antelmi and

Pellegrino, 2022). Independently from the workshop

modality, the collaborative dimension should always

be considered in at-a-distance activities, as observed

in (Vargianniti and Karpouzis, 2020; Antelmi and Pel-

legrino, 2022), where participants play or work col-

laboratively in groups.

Learners Mainly Experience OD in Formal Set-

ting. Including skills useful in the working life of

K-12 learners in educational curricula democratises

the learning process. This practice lets anyone ac-

cess new knowledge regardless of gender, national-

ity, and economic status (Weishart, 2020). This ap-

proach is widely exploited in this context as most of

the overviewed workshops take place in a formal set-

ting, e.g., at school.

OD Workshops and Design Principles. Since one

of the most common learning outcomes explored by

the overviewed OD workshops is data literacy, it

makes sense to compare them according to the data

literacy design principles described in Section 2. Ta-

ble 4 reports the design principles covered by each

OD workshop.

• Most workshops exploit the inquiry principle (P

1

)

scaffolding data analysis, a crucial step for data

literacy.

• The expansion principle (P

2

), which suggests that

learners should start from a representative snap-

shot of the dataset and expand out, is the rarest ful-

filled principle in OD workshops. Usually, schol-

ars either directly deal with the full, large, origi-

nal data set or are encouraged to use a data sub-

set without expanding it in subsequent learning

phases (as represented by the symbol ∼ in the col-

umn P

2

in Table 4).

Based on this consideration, moderators should

pay more attention to the expansion and the per-

sonal data collection principle. Applying this

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

180

principle would help move real OD sets close to

learners instead of asking them to deal directly

with complete data sets that might be too com-

plicated for inexperienced users in their original

format.

• In more than half of the OD workshops, mod-

erators exploit the context principle (P

3

), letting

scholars work with local data. For instance, (Am-

brosino et al., 2018), and (Chen et al., 2014) let

learners work on data concerning local cultural

heritage, (Dickinson et al., 2015), while (Charvat

et al., 2017) exploit local environmental data.

• Most OD workshops focus on foundational com-

petencies rather than practical ones (P

4

). Hence,

OD exploitation is experienced by targeting a

high-level objective, mainly data literacy and (ge-

ographical or cultural heritage) education, as sum-

marised in the column Learning outcome in Ta-

ble 1.

• All the OD workshops cover the STEAM prin-

ciple (P

5

) by letting learners work collabora-

tively on creative activities in remote settings and

in-person meetings. Hence, experiencing OD

through projects and collaboratively seems to be

a common practice.

• The personal data collection principle (P

6

) is the

less covered fundamental. Usually, learners are

encouraged to use already published OD or OGD

rather than work on personally collected data. OD

authoring workshops, such as (Chen et al., 2014),

(Ambrosino et al., 2018), (Dickinson et al., 2015),

or OD exploitation workshops that mix the usage

of personally collected data and publicly avail-

able OD, such as (Antelmi and Pellegrino, 2022),

cover this principle.

None of the workshops, but the one proposed by

(Wolff et al., 2019), who theorised the design prin-

ciples, satisfy all of them. Specifically, all workshops

cover at least two principles (P

4

and P

5

), while the

vast majority do not consider P

2

. Generally speaking,

the design principles defined by (Wolff et al., 2019)

are sufficiently covered by the workshops overviewed

in this survey, and they should be considered as a

guide to inspire upcoming OD initiatives.

Limited Participation to OD Workshops. All

workshops, except the OpenCoesione initiative, in-

volved only dozens of participants. This outcome

may be justified by the experimental nature of the dis-

cussed activities in contrast to OpenCoesione, which

succeeded in reaching a broader consensus thanks to

its structured activities, funded and carried out by the

Italian government in cooperation with the Ministry

of Education and the European Commission (Gasc

´

o-

Hern

´

andez et al., 2018).

Another consideration relates to participants’ age.

These workshops try to bring primary school learn-

ers close to OD (Wolff et al., 2019); still, the tar-

get is pupils older than ten years old, probably be-

cause of the skills required to deal with OD. To further

decrease the age limit, several researchers proposed

game-based learning environments (Dunwell et al.,

2016; Vargianniti and Karpouzis, 2020).

Finally, researchers never explicitly report the per-

centage of females joining such workshops, but gen-

der seems not to introduce significant differences in

OD exploitation (Vargianniti and Karpouzis, 2020).

OD Initiatives and the DLCM Competences. Ta-

ble 3 points out the DLCM skills covered by each OD

initiative, which define competence clusters for data

literacy (see Section 2). As we can note, no skill is in-

cluded in the learning desiderata of all the initiatives.

In particular, the most common skills are included in

17 out of 22 initiatives, while the least covered skill

is considered by only 9 out of 22 initiatives. In more

detail, the most represented skills covered by the ini-

tiatives we reviewed are interpreting (I) and navigat-

ing (N), belonging to the using data cluster, and ob-

serving (O), belonging to the understanding cluster

(which are included in 17 out of 22 initiatives). 16

out of 22 initiatives cover presenting (P), belonging

to the using data cluster, and analysing (A), belong-

ing to the understanding data cluster. 15 out of 22

initiatives cover the collecting (C) skill, while 14 out

of 22 cover the evaluating skill. The less represented

skill is reflecting (R), covered by only 9 out of 22 ini-

tiatives.

Several initiatives, such as (Ambrosino et al.,

2018), (Gasc

´

o-Hern

´

andez et al., 2018), Breaking

news! (Seymoens et al., 2020), and (Antelmi and Pel-

legrino, 2022), cover all the DLCM competencies. 15

out of 22 initiatives include at least five skills, hence

covering at least one skill for each cluster. All initia-

tives considering at most four skills focus on a single

cluster, except (Chen et al., 2014). Generally, when a

single competence cluster is covered, the using data

cluster is the favourite choice (5 out of 8 initiatives

follow this pattern).

In general, the OD initiatives described in this sur-

vey mainly focus on abilities to use rather than under-

stand data. By taking this categorisation into account,

further effort should be invested in letting scholars

understand data and, mainly, in reflecting on how to

adjust data use and communication to minimise the

harmful consequences.

At School of Open Data: A Literature Review

181

6 CONCLUSIONS

OD are published to create value, but limited data

skills are a critical barrier in data exploitation (Janssen

et al., 2012). As K-12 scholars require learning how

to effectively and efficiently deal with data, this ar-

ticle explores the effort invested in the literature to

close the gap between education and OD. Most of

the explored workshops are organised in a formal set-

ting, democratising OD skills, and in-person, exploit-

ing collaboration. While there is a consistent effort to

standardise the expected skills that initiatives in this

context should introduce, we observed the need for

a uniform protocol to enable reproducibility and fair

comparisons. Further effort should be invested in en-

couraging a wider adhesion of participants to break

cultural barriers in OD exploitation successfully. Ex-

amine initiatives to implement OD skills in a much

wider context might imply to analyse efforts invested

in promoting them at universities or out of the learn-

ing settings. Moreover, while in this article we fo-

cus on initiatives to overcome the cultural barriers in

learners, further effort should be invested in system-

atically analyse initiatives to overcome cultural barri-

ers in educators. A critical element is the technical

and pedagogical skills required to those teachers who

would need or want to moderate such initiatives.

REFERENCES

Addone, A., De Donato, R., Palmieri, G., Pellegrino, M. A.,

Petta, A., Scarano, V., and Serra, L. (2021). Novelette,

a usable visual storytelling digital learning environ-

ment. IEEE Access, 9:168850–168868.

Akhtar, N., Tabassum, N., Perwej, A., and Perwej, Y.

(2020). Data analytics and visualization using tableau

utilitarian for covid-19 (coronavirus). Global Journal

of Engineering and Technology Advances.

Ambrosino, M. A., Andriessen, J., Annunziata, V.,

De Santo, M., Luciano, C., Pardijs, M., Pirozzi, D.,

and Santangelo, G. (2018). Protection and preserva-

tion of campania cultural heritage engaging local com-

munities via the use of open data. In Proc. of the 19th

Annual International Conference on Digital Govern-

ment Research.

Anslow, C., Brosz, J., Maurer, F., and Boyes, M. (2016).

Datathons: An experience report of data hackathons

for data science education. In Proceedings of the

47th ACM Technical Symposium on Computing Sci-

ence Education, page 615–620.

Antelmi, A. and Pellegrino, M. A. (2022). Open data liter-

acy by remote: hiccups and lessons. In Symposium on

Open Data and Knowledge for a Post-Pandemic Era.

Argast, A. and Zvyagintseva, L. (2016). Data literacy

projects in canada: Field notes from the open data in-

stitute, toronto node. The Journal of Community In-

formatics, 12.

Bakkalbasi, N., Bauer, K., Glover, J., and Wang, L. (2006).

Three options for citation tracking: Google scholar,

scopus and web of science. Biomedical digital li-

braries, 3:1–8.

Basford, P., Bragg, G., Hare, J., Jewell, M., Martinez, K.,

Newman, D., Pau, R., Smith, A., and Ward, T. (2016).

Erica the rhino: A case study in using raspberry pi

single board computers for interactive art. Electronics,

5:35.

Beheshti, A., Tabebordbar, A., and Benatallah, B. (2020).

istory: Intelligent storytelling with social data. In

Companion Proceedings of the Web Conference 2020,

pages 253–256.

Bhargava, R., Kadouaki, R., Bhargava, E., Castro, G., and

D’Ignazio, C. (2016). Data murals: Using the arts to

build data literacy. The Journal of Community Infor-

matics, 12.

Charvat, K., Cerba, O., Kozuch, D., and Splichal, M.

(2017). Geospatial data based environment in in-

spire4youth. Procedia Computer Science, 104:183–

189.

Chen, C.-P., Shih, J.-L., and Ma, Y.-C. (2014). Using in-

structional pervasive game for school children’s cul-

tural learning. Journal of Educational Technology &

Society, 17(2):169–182.

Coughlan, T. (2020). The use of open data as a material

for learning. Educational Technology Research and

Development, 68(1):383–411.

Crusoe, J., Simonofski, A., Clarinval, A., and Gebka, E.

(2019). The impact of impediments on open govern-

ment data use: Insights from users. In 13th Interna-

tional Conference on Research Challenges in Infor-

mation Science, pages 1–12.

Dib, C. Z. (1988). Formal, non-formal and informal edu-

cation: concepts/applicability. In AIP conference pro-

ceedings, volume 173, pages 300–315. American In-

stitute of Physics.

Dickinson, A., Lochrie, M., and Egglestone, P. (2015). Dat-

apet: Designing a participatory sensing data game

for children. In Proceedings of the British Human-

Computer Interaction Conference, page 263–264.

Donato, R. D., Garofalo, M., Malandrino, D., Pellegrino,

M. A., and Petta, A. (2020). Education meets knowl-

edge graphs for the knowledge management. In Inter-

national Conference in Methodologies and intelligent

Systems for Techhnology Enhanced Learning, pages

272–280. Springer.

Dunwell, I., Dixon, R., Bul, K. C. M., Hendrix, M., Kato,

P. M., and Ascolese, A. (2016). Translating open

data to educational minigames. In 11th International

Workshop on Semantic and Social Media Adaptation

and Personalization, pages 145–150.

Frick

´

e, M. (2019). The knowledge pyramid: the dikw hier-

archy. Knowledge Oeganization, 46(1):33–46.

Gasc

´

o-Hern

´

andez, M., Martin, E. G., Reggi, L., Pyo, S., and

Luna-Reyes, L. F. (2018). Promoting the use of open

government data: Cases of training and engagement.

Government Information Quarterly, 35(2):233–242.

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

182

Janssen, M., Charalabidis, Y., and Zuiderwijk, A. (2012).

Benefits, adoption barriers and myths of open data and

open government. Information systems management,

29(4):258–268.

Kurada, R. R., Ramu, Y., and Pattem, S. (2021). Lessoning

geospatial visualizations on real-time data. In 2021

IEEE International Conference on Computation Sys-

tem and Information Technology for Sustainable So-

lutions (CSITSS), pages 1–6.

Mart

´

ın-Mart

´

ın, A., Orduna-Malea, E., Thelwall, M., and

L

´

opez-C

´

ozar, E. D. (2018). Google scholar, web of

science, and scopus: A systematic comparison of ci-

tations in 252 subject categories. Journal of informet-

rics, 12(4):1160–1177.

Mongeon, P. and Paul-Hus, A. (2016). The journal coverage

of web of science and scopus: a comparative analysis.

Scientometrics, 106:213–228.

Morelli, N., Mulder, I., Pedersen, J. S., Jaskiewicz, T.,

G

¨

otzen, A. d., et al. (2017). Open data as a new com-

mons. empowering citizens to make meaningful use

of a new resource. In International Conference on In-

ternet Science, pages 212–221.

Obie, H. O., Chua, C., Avazpour, I., Abdelrazek, M.,

Grundy, J., and Bednarz, T. (2020). Authoring logi-

cally sequenced visual data stories with gravity. Jour-

nal of Computer Languages, 58:100961.

Open Knowledge Foundation (2013). Defining open data.

https://blog.okfn.org/2013/10/03/defining-open-data,

[Online, Last access November 2022].

Piedra, N., Chicaiza, J., L

´

opez, J., and Caro, E. T. (2016).

Integrating oer in the design of educational mate-

rial: Blended learning and linked-open-educational-

resources-data approach. In Global Engineering Edu-

cation Conference, pages 1179–1187.

Piedra, N., Chicaiza, J., L

´

opez, J., and Caro, E. T. (2017). A

rating system that open-data repositories must satisfy

to be considered oer: Reusing open data resources in

teaching. In Global Engineering Education Confer-

ence, pages 1768–1777.

Renuka, T., Chitra, C., Pranesha, T., G., D., and M., S.

(2017). Open data usage by undergraduate students.

In 5th IEEE International Conference on MOOCs, In-

novation and Technology in Education, pages 46–51.

Rubin, A. (2021). What to consider when we consider data.

Teaching Statistics, 43(S1):S23–S33.

Ruijer, E., Grimmelikhuijsen, S., van den Berg, J., and Mei-

jer, A. (2020). Open data work: understanding open

data usage from a practice lens. International Review

of Administrative Sciences, 86(1):3–19.

Saddiqa, M., Kirikova, M., Magnussen, R., Larsen, B., and

Pedersen, J. M. (2019a). Enterprise architecture ori-

ented requirements engineering for the design of a

school friendly open data web interface. Complex Sys-

tems Informatics and Modeling Quarterly, (21):1–20.

Saddiqa, M., Larsen, B., Magnussen, R., Rasmussen, L. L.,

and Pedersen, J. M. (2019b). Open data visualization

in danish schools: A case study. In Proc. of Intern.

Conf. in Central Europe on Computer Graphics, Visu-

alization and Computer Vision.

Saddiqa, M., Magnussen, R., Larsen, B., and Pedersen,

J. M. (2021). Open data interface (odi) for sec-

ondary school education. Computers & Education,

174:104294.

Saddiqa, M., Rasmussen, L., Magnussen, R., Larsen, B.,

and Pedersen, J. M. (2019c). Bringing open data

into danish schools and its potential impact on school

pupils. In Proc. of the 15th International Symposium

on Open Collaboration.

Seymoens, T., Van Audenhove, L., Van den Broeck, W.,

and Mari

¨

en, I. (2020). Data literacy on the road:

Setting up a large-scale data literacy initiative in the

databuzz project. Journal of Media Literacy Educa-

tion, 12(3):102–119.

Shamash, K., Alperin, J. P., and Bordini, A. (2015). Teach-

ing data analysis in the social sciences: A case study

with article level metrics. Open Data as Open Educa-

tional Resources, page 49.

Susha, I., Gr

¨

onlund,

˚

A., and Janssen, M. (2015). Organi-

zational measures to stimulate user engagement with

open data. Transforming Government: People, Pro-

cess and Policy.

Tovar, E. and Piedra, N. (2014). Guest editorial: open

educational resources in engineering education: var-

ious perspectives opening the education of engineers.

IEEE Transactions on Education, 57(4):213–219.

Trentini, A. and Scaravati, S. (2020). Raising curiosity

about open data via the ’physiradio’ musicalization iot

device. Data Science Journal, 19:39.

Van Audenhove, L., Van den Broeck, W., and Mari

¨

en, I.

(2020). Data literacy and education: Introduction and

the challenges for our field. Journal of Media Literacy

Education, 3:1–5.

Vargianniti, I. and Karpouzis, K. (2020). Using big and

open data to generate content for an educational game

to increase student performance and interest. Big Data

and Cognitive Computing, 4(4).

Watson, J. (2017). Open data in australian schools: Taking

statistical literacy and the practice of statistics across

the curriculum. In Data visualization and statistical

literacy for open and big data, pages 29–54.

Weishart, J. E. (2020). Democratizing education rights.

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal, 29:1.

Windhager, F., Mayr, E., Schreder, G., and Smuc, M.

(2016). Linked information visualization for linked

open government data. a visual synthetics approach

to governmental data and knowledge collections.

JeDEM-eJournal of eDemocracy and Open Govern-

ment, 8(2):87–116.

Wolff, A., Wermelinger, M., and Petre, M. (2019). Explor-

ing design principles for data literacy activities to sup-

port children’s inquiries from complex data. Interna-

tional Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 129:41–

54.

´

Alvarez Otero, J., L

´

azaro, M., and JesusG, M. (2018). A

cloud-based giscience learning approach to spanish

national parks. European Journal of Geography, 9:6–

20.

At School of Open Data: A Literature Review

183