Implementing an Intersectoral Telemedicine Network in Rural Areas:

Evaluation from the Point of View of Telemedicine Users

Domenic Sommer

a

, Sebastian Wilhelm

b

, Diane Ahrens

c

and Florian Wahl

d

Deggendorf Institute of Technology, Technology Campus Grafenau, Hauptstrasse 3, 94566 Grafenau, Germany

{domenic.sommer, sebastian.wilhelm, diane.ahrens, florian.wahl}@th-deg.de

Keywords:

Telemedicine, Remote Medicine, Delivery of Healthcare, Ehealth, Rural Health, Germany.

Abstract:

Telemedicine (TMed) is becoming popular due to the growing number of elderly and the shortage of health-

care workers. In Germany, TMed is rarely part of rural healthcare, and the research state is limited. To

improve healthcare and to research the conditions under which TMed can be used in German rural areas, an

intersectoral, TMed network was set up from July 2018 to Oct. 2020 and evaluated with mixed methods, in-

cluding qualitative interviews and quantitative feedback forms. Seven Use-Cases (UCs) were implemented in

the dimensions: (i) home visits (n = 170), (ii) patient video consultation (n = 30), (iii) intensive care (n = 15),

(iv) mountain accident (n = 6), (v) wound management (n = 6), (vi) caregiver video consultation (n = 3) and

(vii) electronic health record (n = 10). Our study indicates that digitally supported general practitioner (GP)-

home visits and intensive care are the most frequent UCs. TMed is satisfactory and leads to advantages for

rural healthcare. However, vital data transmission and the electronic health record (eHR) were less in demand

due to high preparation efforts. Findings from previous studies can be confirmed. Facilitators for TMed who

should be considered and further researched are: training on digital literacy including awareness-rising, fi-

nancing, cross-institutional documentation, and suitable mobile network infrastructure.

1 INTRODUCTION

European Challenges. Increasing multi-morbidity

and treatments for chronic diseases in an aging soci-

ety in Western Europe are putting pressure on health

systems. In Germany, one in five people is over 65

years of age (Dudel, 2018, p. 5), and rising life ex-

pectancy leads to an increase in the number of elderly

requiring treatment in Europe (European Parliament,

2021). There are several challenges Health Service

Providers (HSPs) face: (i) disciplines become more

specialized, (ii) services get increasingly fragmented,

(iii) overall complexity is increasing and (iv) no inef-

ficiencies can be afforded due to the shortage health-

care workers (HCWs) (Valentijn et al., 2013; Hack-

mann and Moog, 2010; Tsiasioti et al., 2020).

Rural Challenges. Equal opportunities between ur-

ban and rural areas and the same access to health

services are a priority for many European countries

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2581-513X

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4370-9234

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9905-7442

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1163-1399

(Weingarten and Steinf

¨

uhrer, 2020). Many rural gen-

eral practitioner (GP) vacancies won’t be filled in

the future because there often is no succession plan-

ning (Kopetsch, 2010; Laschet, 2019). Another chal-

lenge is that young people are the backbone of rural

development, but due to urbanization, they are miss-

ing in rural healthcare jobs, and the role of informal

caregiver remains unfilled (Hennig, 2019). Therefore,

the rural elderly are increasingly dependent on profes-

sional health and care services in rural regions (Bay-

erisches Landesamt f

¨

ur Statistik, 2019b).

In rural areas, there is a shortage of rural

HCWs and conversely a high demand for health ser-

vices (Hackmann and Moog, 2010; Tsiasioti et al.,

2020). In addition, a large portion of work time

of HCWs is spent on not direct patient care tasks

(e.g., administration or travel). Some German re-

gions are sparsely populated with, e.g., 80 residents

per km

2

, and travel times for home visits or clinic ad-

missions take longer than in cities (Bayerisches Lan-

desamt f

¨

ur Statistik, 2019a, p. 14). The fact that ru-

ral HSPs travel long distances to visits or examina-

tions (e.g., vital parameter checks) is costly, ineffec-

tive and reduces the attractiveness of the health pro-

fession (Meyer, 2020). In addition, not only obtaining

Sommer, D., Wilhelm, S., Ahrens, D. and Wahl, F.

Implementing an Intersectoral Telemedicine Network in Rural Areas: Evaluation from the Point of View of Telemedicine Users.

DOI: 10.5220/0011755500003476

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2023), pages 15-27

ISBN: 978-989-758-645-3; ISSN: 2184-4984

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

15

timely care is critical, even the time for patient care is

reduced as well as medical and paramedical staff are

burdened. The patient’s situation is similar because

mobility is reduced with increasing age and house

visits have capacity bottlenecks. Furthermore, they

often have to deal with a lack of specialist support

in close vicinity, which makes it difficult to get treat-

ment for complex conditions without traveling longer

distances (L

¨

offler et al., 2021). Treatment delays can

lead to worse health outcomes (Meyer, 2020).

TMed as a Solution. Telemedicine (TMed) is us-

ing medical data exchange from distinct locations via

electronic communication to improve patient’s health

and bridge distances (Schwab, 2020). Since COVID-

19, protecting vulnerable patients from infections has

become more important in rural areas, where the

loss of personnel becomes directly noticeable (Kn

¨

orr

et al., 2022). In rural areas, HSPs serve a remarkably

vital role in the care of their communities, and TMed

can contribute to infection protection. TMed even has

the potential to close the gap in healthcare access and

alleviate disparities between rural and urban health-

care delivery.

Research Focus. The main contribution is to show

how TMed in german rural areas can improve health

care. Contrary to prior studies, our applied study

presents a multisided picture of rural TMed, uncov-

ers barriers, and shows how individual TMed applica-

tions fit into a bigger intersectoral network.

The remaining paper is structured as follows: We re-

view the current literature on rural TMed in Section 2,

highlighting the existing barriers and research gaps.

In Section 3, we present how we established an in-

tersectoral TMed network (Subsection 3.1) and eval-

uated it (Subsection 3.2). The results are presented in

Section 4. The paper ends with a discussion in Sec-

tion 5, a conclusion, and an outlook in Section 6.

2 RELATED WORK

The scientific community dealt with TMed and tel-

erehabilitation, focusing on mental health, home care,

primary care, and emergencies (Butzner and Cuf-

fee, 2021; Speyer et al., 2018). Plenty of re-

search even focused on teleconsultation as a techni-

cal application for communication between profes-

sionals and patients (Yamano et al., 2022). Due to

COVID-19, the publication record has increased sig-

nificantly (Mbunge et al., 2022; S¸ahin et al., 2021).

2.1 International Perspective

Regarding international studies, much of the applied

science is being carried out in emerging, and develop-

ing countries since TMed usually represents the only

care option here. For example, in the Himalayan re-

gion, patients were provided with TMed (treatment

and health education) in their homes and rural care

centers because of a rural physician shortage (Amatya

et al., 2022; Ganapathy et al., 2019).

Outcomes and Effects. Most high-level TMed

evidence focus on clinical outcomes and cost-

effectiveness, with findings that TMed is at least as

effective as standard care and can reduce costs for pa-

tients as well as HSPs (Speyer et al., 2018; Zhang

et al., 2022b; Butzner and Cuffee, 2021). The cost-

benefit analysis is complex since TMed first requires

investments and pay off later (Goharinejad et al.,

2021). Eliminating the need for travel, TMed can help

reduce the cost of care for patients and HSP (Zhang

et al., 2022a). TMed is also convenient, and patients

often recommend it to others (Sekhon et al., 2021).

Furthermore, TMed advantage people with limited

mobility or social isolation (Banbury et al., 2018).

The outcome of TMed is greater than saving time

and costs in overall care. TMed offers versatile op-

portunities for elderly, multimorbid, and mobility-

impaired people and can compensate for dispari-

ties (Batsis et al., 2019). Teleconsultations can pre-

ventively avoid hospital admissions and thus a high

burden on patients due to a new environment and

starting treatment too late (Batsis et al., 2019). In

particular, the connection of medical devices, such as

an ECG or wearables, can monitor health status and

complement existing care (Yamano et al., 2022).

There are several advantages to TMed in rural ar-

eas, including the (i) ability to reach underserved pop-

ulations (better healthcare access), (ii) the provision

of care at a lower cost and (iii) the potential to im-

prove clinical outcomes (Haleem et al., 2021). The

most obvious TMed benefit is the reduction of infec-

tion risks and increased protection against COVID-19

in fragmented health care (Mbunge et al., 2022). Fur-

ther, patient satisfaction with TMed is good, and pa-

tients accept them (Sekhon et al., 2021; Batsis et al.,

2019). HCW also show overall satisfaction, accep-

tance and see opportunities for better relationships

with patients (Odendaal et al., 2020). TMed also

transforms the work of HCWs, creating flexibility and

better coordination in care so that resource utilization

can be improved (Butzner and Cuffee, 2021).

Outcomes depend on applications and clinical pic-

ture: In diabetes, an improvement in blood glucose

ICT4AWE 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

16

control and self-management of health can be ob-

served (Zhang et al., 2022a). TMed also has psy-

chological effects, reducing negative emotions and

enhancing medication adherence (Ma et al., 2022).

TMed also decreases hospital admissions and severe

adverse effects (Batsis et al., 2019). Many exist-

ing studies are biased and consider only one specific

disease (Batsis et al., 2019), although society gets

more multimorbid (The American Geriatrics Society,

2012). This raises the question about the transferabil-

ity of existing studies, shown in Table 1.

Table 1: International evidence on TMed in rural areas.

Findings of Reviews Source

Better or comparable

outcomes (TMed &

face-to-face)

(Goharinejad et al.,

2021; Batsis et al.,

2019; S¸ahin et al.,

2021; Speyer et al.,

2018)

Decreased direct and

indirect costs for pa-

tient & health service

(Butzner and Cuffee,

2021; Haleem et al.,

2021; Speyer et al.,

2018; Zhang et al.,

2022b)

Better resource alloca-

tion & staff relief

(Butzner and Cuffee,

2021)

Satisfaction and accep-

tance by patients &

healthcare workers

(Sekhon et al., 2021;

Butzner and Cuffee,

2021; Mbunge et al.,

2022)

Outcomes are limited

due to heterogeneity:

rural areas need further

research

(Butzner and Cuffee,

2021; Speyer et al.,

2018; Yamano et al.,

2022; Banbury et al.,

2018; Batsis et al.,

2019; S¸ahin et al.,

2021)

Barriers and Facilitating Factors. The main barri-

ers to implementing TMed in rural areas are: (i) lack

of infrastructure, (ii) limited resources and (iii) lack of

provider training. To provide remote access to medi-

cal care, TMed requires a reliable internet connection

in remote areas. While most of the population has ac-

cess to broadband internet, the picture is switching for

mobile applications in rural areas, where connectiv-

ity gaps exist (Baake and Mitusch, 2021). Insufficient

mobile connectivity makes it difficult to provide or re-

ceive care via TMed. In addition, emerging and devel-

oping countries struggle with affordable internet con-

nection and electricity isn’t always available (Oden-

daal et al., 2020). However, the reliability of solu-

tions is especially (esp.) important when consulting

emergencies (Yamano et al., 2022). In this context,

technical support is important. Furthermore, the in-

teroperability of TMed solutions, esp. a unified elec-

tronic health record (eHR), will determine the success

or failure of TMed (Haleem et al., 2021).

Time must be invested first to find and train the

resources needed for TMed deployment. Similarly,

the training of health workers is quite important in

this context, and the solutions must be user-friendly

and integrate with existing systems (Odendaal et al.,

2020). Accessibility can be essential because hear-

ing problems or sign language can be a problem for

current TMed (S¸ ahin et al., 2021).

The Chochrane Library revealed that concerns ex-

ist in the form of supervision, threatening one’s com-

petence, and fears of being overworked and deperson-

alized (Odendaal et al., 2020). These should be ad-

dressed to promote TMed. Digital literacy is limited

in some cases. For successful TMed deployment, user

training and guidance were needed (Banbury et al.,

2018). Also, concerns exist about the reliability of

TMed, and sometimes interventions can’t be deliv-

ered with TMed at all (Sekhon et al., 2021). Some in-

terventions even require additional people to perform

physical exams. Further research on barriers and fa-

cilitating factors are needed to accelerate the uptake

of TMed (Banbury et al., 2018; S¸ahin et al., 2021).

2.2 National Perspective

National Achievements. Germany’s TMed efforts

are focused on providing access to care for rural

and under-served populations, enhancing coordina-

tion, and lowering costs. One of the notable german

TMed efforts is the creation of legal foundations (e.g.,

e-health law and digital healthcare act) for imple-

menting, billing, and TMed delegation of medical ser-

vices. Even though the government wants to advance

TMed, some regulatory burdens, such as changing

professional codes, billing arrangements, and indica-

tion for TMed, still need to be changed (Peine et al.,

2020). The TMed efforts are slowly translating to

countrywide care, although COVID-19 leads to an in-

creased TMed demand (Peine et al., 2020). Much

TMed applications are piloted and focused on spe-

cific diseases, esp. cardiovascular disease or mental

health. Furthermore, most applications include cer-

tain regions or professions (Allner et al., 2019).

Further Needs. Various associations, such as the

German Society for TMed (DGTELEMED) and na-

tional alliances (e.g., Bavarian TMed Alliance), pro-

mote TMed. Regional networks or projects exist

within funding limits and have specific Use-Cases

Implementing an Intersectoral Telemedicine Network in Rural Areas: Evaluation from the Point of View of Telemedicine Users

17

(UCs), e.g., stroke care, mental health, and primary

care. Partly complex applications such as the diagno-

sis of dementia via videoconferencing or TMed sup-

ported stroke units have been well-tested (Barth et al.,

2018; Mathur et al., 2019). In addition, previously

applied science on TMed is often unsystematic, and

many results aren’t published (Allner et al., 2019).

Lack of Transferable Research. Table 2 shows

that experience is limited in the field of TMed in

Bavaria with promising effects, although further re-

search is required (Black et al., 2011). National stud-

ies have shown a broad acceptance of TMed by health

professionals and patients, but there is untapped po-

tential in the actual use (Muehlensiepen et al., 2021;

Kirchberg et al., 2020; Techniker Krankenkasse,

2022; van den Berg et al., 2009; von Solodkoff et al.,

2020). Many health professionals share the assess-

ment that TMed measures improve care and repre-

sent a solution strategy for current challenges (Beck-

ers and Stellmacher, 2021, p. 60).

The elaborated international outcomes seem sim-

ilar, but there isn’t enough research to derive a clear

conclusion for Germany (Kn

¨

orr et al., 2022). Most

studies have low evidence levels, and the effects are

unclear. Some studies attest to a potential positive

benefit of TMed in the form of a reduction in the

workload of GPs, although the increase in quality

of care and safety hasn’t yet been conclusively clari-

fied (Black et al., 2011; Grohs and Thiess, 1997). The

effects always depend on the application scenario.

esp. treating skin diseases and wounds is a time-

saving and effective TMed application field (Eber

et al., 2019; J

¨

unger et al., 2019). Furthermore, om-

nipresent economic benefits, such as saving time and

money by avoiding unnecessary clinic visits, reducing

travel time, and utilizing more GPs working time for

direct patient care, are fulfilled by TMed. Nonethe-

less, many studies can’t calculate exact savings (Gen-

sorowsky et al., 2021). Yet, it should be clear by

the nature of TMed that elderly with limited mobil-

ity benefit from positive effects in their quality of life

through telediagnostics (Bohnet-Joschko and Stahl,

2019; Partheym

¨

uller et al., 2019).

Explore Barriers Nationally. Nationally, barri-

ers reducing the use of TMed exist mainly struc-

turally (Peine et al., 2020). Barriers are related to fi-

nancing, technical infrastructure, fear of misdiagnos-

ing, lack of interfaces, and missing resources, e.g.,

GP shortage (Weißenfeld et al., 2021). The indica-

tions for TMed are also limited by the impossibility

of examining patients directly physically, i.e., either

self-tests or non-medical specialists are needed (von

Solodkoff et al., 2020). The digital literacy of HCWs

primarily needs improvement, esp. in the legal as-

pects and data safety of TMed (Kirchberg et al.,

2020). Privacy knowledge and ambiguity regarding

terminology, digital treatment concepts, and evalua-

tion or improvement of TMed measures are demand-

ing (K

¨

ohnen et al., 2019; von Solodkoff et al., 2020).

The barriers for TMed can reduce use and accep-

tance. The literature cited so far doesn’t explicitly

examine the barriers nationally, doesn’t communicate

transparently, and doesn’t compare effects between

rural and urban TMed. We are unaware of any study

examining barriers to TMed in rural areas. Further-

more, international experience can only be transferred

to Germany to a limited extent due to the country’s

special structure and form of government organiza-

tion (Kidholm et al., 2012). This is exactly why fur-

ther research in the field is important.

3 METHODOLOGY

From July 2018 to October 2020, we implemented an

intersectoral TMed network in a German rural region.

We focus on UCs that deliver diagnostics and therapy

to the patient or HCWs due to audio-visual commu-

nications, the transmission of vital data between GPs

and non-physician staff, and a commercial eHRs.

First, we describe the TMed network and the consid-

ered UCs in Subsection 3.1, followed by a description

of the evaluation approach with Subsection 3.2.

3.1 Framework, Setup, and Use-Cases

After analyzing the requirements and opportunities,

we implemented an intersectoral TMed network in

Lower Bavaria consisting of several HSPs: one GP,

two regular clinics, one special clinic, two nursing

homes, and one intensive care provider with residen-

tial care communities. Furthermore, a mountain shel-

ter without para-/medical professionals was added to

the network (see UC 4). The HSPs relations are

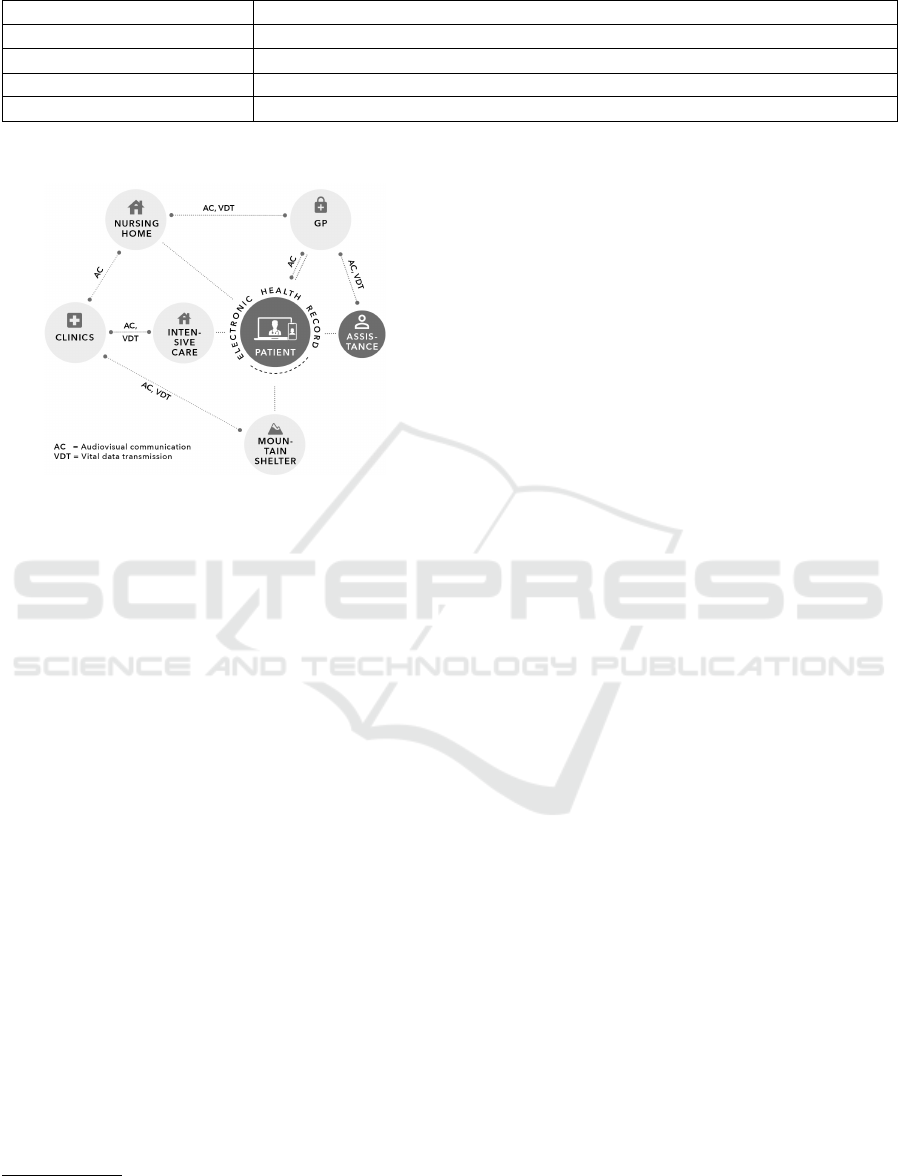

shown in Figure 1.

Applied Technology. Various HSPs were equipped

gradually with TMed gear available in 2018. We

chose the equipment after market research in which

we considered: security, interfaces, usability, and

training. Because prior studies showed that common

documentation is vital, a commercial eHR Vitabook

®1

was used. For audio-visual communication as well

as the mobile and stationary transmission of video,

1

www.vitabook.de, accessed on 2023-02-06

ICT4AWE 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

18

Table 2: Bavarian TMed projects, cf. (Jedamzik, 2022).

Project title content

eNurse

a

TMed network of specialists and GPs, established itself as an enterprise

SPeed

b

Cross-sector care record, TMed-network of GPs & geriatric-/ nursing homes

TEMPiS

c

TMed stroke care with special & regular clinics

Gesundheitsversorgung 4.0

d

GPs, pharmacy, nursing service & patients communicate via TMed

a

High Franconia

b

Ingolstadt Region

c

entire Bavaria

d

High Franconia

Figure 1: HSPs relationship within the TMed network.

images, and text, MEYDOC

®2

was used. For the

transmission of vital data, such as electrocardiogram

(ECG) data, Heart Rate Variability (HRV)rate, Blood

pressure (BP) and oxygen saturation, we used the mo-

bile medical product DynaVision

3

Use-Cases (UCs). With the described equipment,

we investigated seven TMed UCs as shown in Table 3.

In UC 1, we investigated TMed support of home

visits. Medical assistants could contact the GP audio-

visually during home visits, transmit vital data, and

carry out certain activities by delegation. The GP

also offered video consultations for patients (UC 2)

directly to reduce the risk of COVID-19 infections.

In UC 3, we connected an intensive care service

with a specialist clinic for respiratory diseases. The

TMed coordination and optimization of ventilation

parameters between the two HSPs were investigated

with online visits scheduled or organized ad hoc.

In UC 4, non-medical staff at the mountain shelter

were networked with the hospital to support rescue or

first aid in the event of mountain accidents.

During the project, it emerged that digital support

for wound management in nursing represents a useful

field of application (UC 5). Furthermore, we set up

digital consultation hours with the GP and the care

facility to discuss critical patients before the weekend.

2

www.meydoc.de, accessed on 2023-02-06

3

No longer available; supplier: www.eurovation.de

In all UCs, the eHR should be used as uniform

documentation and information basis (UC 7).

3.2 Evaluation Methodology

For evaluating the conditions of rural TMed and to an-

swer the research question on how TMed can improve

rural health care, a mixed-method approach was used

following Kuckartz (Kuckartz, 2014).

Quantitative Approach. Quantitatively the case

numbers, reasons for use, UCs as well as satisfaction

after each consultation were recorded using analog

feedback forms. Corresponding feedback forms were

filled out by GP, intensive care, and nursing home

staff. The data about the consultations were entered

and analyzed with IBM SPSS

®

Ver. 24.

Because of limited case numbers (see Table 4),

data analysis was only descriptive. The feedback

forms and the raw data will be provided as supple-

mentary material to this article.

Qualitative Approach. The qualitative approach

was intended to clarify the question of the feasibil-

ity and acceptance of TMed applications in practice,

as well as to record the challenges (i.e., the barri-

ers) and the subjectively perceived outcomes in care

multi-dimensionally. Therefore, seven guided inter-

views were conducted with non- and paramedical

staff (nursing home manager, nurse, medical assis-

tant, wound manager, critical care nurse) and the med-

ical profession (GP and specialist physician) from the

TMed network. For this purpose, we used a guide-

line with five main topics, including: (i) biographical

context (ii) understanding and acceptance of TMed

(iii) coordination and integration (iv) facilitating and

inhibiting factors (v) outcomes relevant to care

The interviews were transcribed and analyzed

using qualitative content analysis according to

Mayring (Mayring, 2010). MAXQDA Vers. 20 was

used to support the classification system, consisting of

six categories. The classification system is provided

as supplementary material to this article.

Implementing an Intersectoral Telemedicine Network in Rural Areas: Evaluation from the Point of View of Telemedicine Users

19

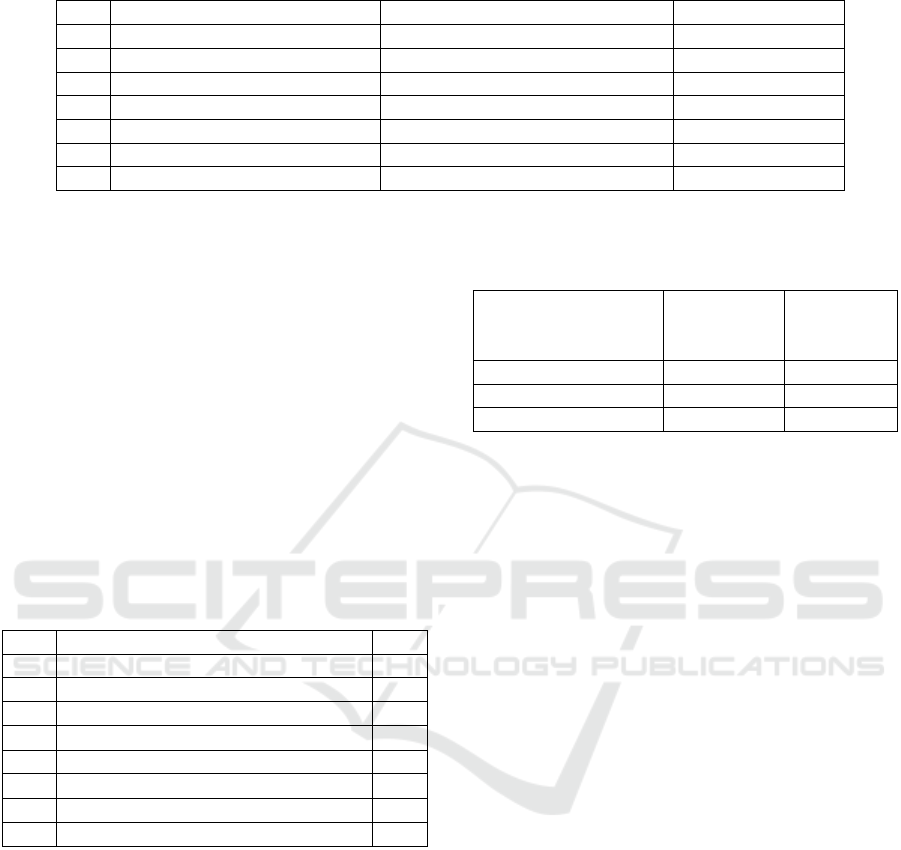

Table 3: Investigated UCs with involved HSPs and periods.

No. Use Cases Providers Duration

1 Home visits GP 11.2018 - 10.2020

2 Video consultation for patients GP 05.2020 - 10.2020

3 Intensive care care service, specialist clinic 03.2020 - 10.2020

4 Mountain accident regular hospital, mountain shelter 08.2019 - 11.2019

5 Wound management nursing home, regular hospital 07.2020 - 10.2020

6 Digital consultation for care nursing home, GP 09.2019 - 11.2019

7 eHR GP 02.2019 - 10.2020

4 RESULTS

The presentation of results follows the UCs and ends

structurally with contents of the qualitative analysis

on success factors and barriers of TMed.

4.1 Case Numbers and Applications

During the survey period, the audio-visual commu-

nication application was mainly used by GPs (170

cases) and intensive care units (15 cases). Further rel-

evant case numbers resulted from COVID-19 in video

consultation hours for patients (30 cases). Table 4

gives an overview about the investigated UCs.

Table 4: UC with case number.s

No. Use Case n

1 Home Visits 170

2 Video Consultation for Patients 30

3 Intensive Care 15

4 Mountain Accident

*

6

5 Wound Management 6

6 Digital Consultation Hour for Care

*

3

7 Electronic Health Record 10

∑

TMed applications, connections 240

*

only test runs, no real emergencies and live environment

Home Visits (GP ⇔ Medical Assistance). The

possibility for medical assistants to contact the GP

audio-visually during home visits was the most

common UC (n = 170). A total of 1.147 home visits

were carried out from Sept. 2018 to Oct. 2020. In

170 cases (14.8 % of all home visits), the medical

assistant needed to contact the GP via TMed. Of

these 170 cases, communication wasn’t possible in

44 cases (25.9 %). The results on (un)successful and

not required audio-visual communication between

medical assistants and GP during home visits in the

studied period are presented in Table 5.

Table 5: Audio-visual communication between medical as-

sistance and GP during a total of 1.147 home visits.

to all only to

home-visits tele-visits

Connection n % n %

successful 126 11.0 126 74.1

not successful 44 3.8 44 25.9

not required 978 85.2 - -

According to the feedback form, the reason for the

failed connections of 25.9 % (n = 44) is a lack of mo-

bile network coverage. On a query of satisfaction, a

sum of N = 345 responses was made, of which were

n = 273 (79.1 %) positive and n = 72 (20.9 %) neg-

ative. Overall the TMed users are pleased. With the

quantitative negative answers, 67 times (92.1 %) the

network connection, e.g., the transmission speed, was

criticized. Problems with the sound quality (3.2 %)

and picture quality (2.0 %) were marginal. The quali-

tative interviews confirm overall satisfaction and net-

work connection as a barrier 4.2.

Analyzing the successful connections shows that

clarification of wound care, with 38.3 % (n = 64), is

the most common reason for using audiovisual com-

munication, followed by medication management,

with 26.4 % (n = 44) and unforeseen symptoms in

the case of unexpected side effects or a deteriora-

tion in health with 4.6 % (n = 36). Even in 9.0 %

(n = 15), patients requested TMed actively an audio-

visual contact with the doctor. In 4.8 % (n = 8) of the

cases, audio-visual communication was used to clar-

ify queries regarding documents from other service

providers, such as prescriptions or discharge letters

from the hospital.

Video Consultation (GP ⇔ Patients). During the

COVID-19 pandemic, the GP established a video con-

sultation service for patients. 30 patients used this of-

fer at least once. During the interviews, the GP stated

that video consultation is an advantageous offer, al-

though older patients need guidance and a period of

acclimatization. Another interviewee, the Nursing

ICT4AWE 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

20

Home Manager (NH-Manager) (para. 13), who uses

video consultation privately to discuss laboratory re-

sults, emphasizes the savings in time for working peo-

ple and the protection against viruses: “TMed allows

me [. . . ] to discuss my medical needs with a doctor

at a controlled time. [. . . ] For me, waiting times in

the doctor’s office are wasted time and harbor risks of

infection.” Furthermore, indications of health benefits

are given by the same interviewee, the NH-Manager

(para. 13): “I would also go to the doctor more be-

cause of the elimination of waiting time and do less

self-therapy.”

4

Intensive Care (Nursing Service ⇔ Specialist

Clinic). Audiovisual visits (n = 15) between the

intensive care service and the specialist clinic were

used to coordinate ventilation parameters and discuss

saturation drops, blood gas analysis, secretion man-

agement, and patient mobilization with experts. For

organizing the audiovisual visits, pre-appointment

was revealed practicably. The visits were conducted

in the shared intensive care flats (n = 11) and also in

the mobile nursing service (n = 4). The case numbers

in this UC from March 2020 to October 2020 are

outlined in Table 6.

Table 6: Use and successful/not-successful application of

TMed for audio-visual communication in critical care, de-

pending on Care Flats (N = 51) and Home Visits (N = 24).

Care Flats Home Visits

Connection n % n %

successful 11 21.6 4 16.7

not successful 0 0.0 1 4.2

not required 40 78.4 19 79.2

The interviews with the intensive care specialist

indicate high satisfaction with the transmission and

image quality over the entire application period. The

feedback forms and the interviews HCWs mentioned

that using an electronic stethoscope would be useful.

Mountain Accident (Mountain Shelter ⇔ Clinic).

During our study, no emergencies or accidents oc-

curred during the test period, so there was no need for

actual operation. Therefore only test runs (n = 4) with

the audio-visual communication could be performed,

but they were successful with positive feedback. Non-

medical staff from the mountain shelter expressed that

user-friendliness was given.

No technical problems regarding connection es-

tablishment and transmission quality occurred, as

only General Packet Radio Service (GPRS) reception

4

All interview statements were translated from German

of the vital data transmission with DynaVision was re-

quired. In the parallel running video communication,

there were occasional dropouts because MEYDOC

®

required higher data rates, and network coverage was

limited to our mountain shelter.

For the medical staff of the regular clinic, our test

runs were an additional burden and a disruptive factor

in the daily clinic routine. Although the test runs with

the mountain shelter were assessed as useful in princi-

ple, the value added for the clinic wasn’t seen. In the

interview, the GP stated that he saw the advantage but

that this special UC would need to be implemented in

larger concepts with mountain rescue and the avail-

ability of much TMed-supported rescue points.

Wound Management (Nursing Home ⇔ Clinic).

We connected the nursing home to a regular clinic’s

wound specialist (special nurse education) and carried

out digital wound management (n = 6). Interviewing

the NH-Manager shows positive perceptions regard-

ing wound management: The networking with the

clinical wound manager showed above all that sim-

ple audio-visual applications, without special cam-

eras, with commercially available tablets, can lead to

an adequate assessment of the wound and thus support

the care. Interviewing the nurse showed a satisfactory

perception of nursing staff and home residents. From

the nursing staff’s perspective, the ward rounds with

a clinical wound manager enrich their work and con-

tribute to empowerment. Since, due to legal condi-

tions and a contract with a special wound care firm,

it was impossible to rely exclusively on wound visits

with the clinic, an analog on-site wound assessment

was carried out in parallel. The video visits and the

analog counterpart are comparable in outcomes, i.e.,

they lead to identical care proposals.

Digital Consultation Hour for Care (Nursing

Home ⇔ GP). In this UC, only successful tests (n =

3) in audio-visual communication for digital consul-

tations with the GP to avoid hospital admissions at

weekends were carried out. The digital consultations

weren’t extended to further live operations (n = 0) be-

cause of ”the good weekday doctor presence in the

nursing home” and ”unpredictability of emergencies,

e.g., falls”, as said by the NH-Manager. The GP inter-

view even showed that it makes more sense to imple-

ment a TMed network with the on-call medical ser-

vice to clarify emergencies that occur on weekends

and avoid unnecessary travel.

Electronic Health Record (GP). A limited number

of patients (n = 10) that used eHR at least once and

the interview with the GP show that there was less

Implementing an Intersectoral Telemedicine Network in Rural Areas: Evaluation from the Point of View of Telemedicine Users

21

eHR acceptance during the project period. However,

GPs and research associates created promotional fly-

ers and educated through citizen events. Only ten pa-

tients actively used the eHR. The GP states in inter-

views that benefits of the eHR weren’t always seen,

and HSPs, which actively use the eHR, were just a

few. High-aged patients aren’t ever already equipped

with mobile devices or weren’t digitally experienced

enough to use the eHR, which limits accessibility.

4.2 Qualitative Assessment

TMed-Perceptions. The interviews reveal that the

perception of TMed is largely positive among the sur-

veyed paramedical and medical staff (3.2). On the

HSP side, there were high expectations, and TMed

was seen as a chance to transfer expertise, save time,

and utilize resources (wound manager, para. 6; medi-

cal assistant, para. 4). The use of TMed “is fun” (criti-

cal care nurse (CC-Nurse), para. 16), “should be used

as often as possible” (CC-Nurse, para. 38), and “en-

riches skills on many levels” (nurse, para. 28).

But at some points, the interviews reveal fears

about liability, the anxiety of extra work for non-

physician staff, and fear of another physician’s status

and estrangement in patient relations (IP 5, para. 34).

The GP (para. 35) even remarked: “The fear of

making wrong decisions under time pressure is om-

nipresent. After all, even if TMed brings a lot of re-

lief, I am unsure if TMed has the same quality instead

of being on-site.” TMed was new for the HSPs, and

initially, there were some uncertainties.

Even though patients weren’t interviewed, the

HCW implied the satisfaction of patients. Similarly,

patients explicitly desired audio-visual contact with

the GP. The positive patient acceptance is evidenced

by an interview statement: “Patients have perceived

TMed positively and have been pleased with the new

opportunities. The uncomplicated way of consulting

experts via TMed was appreciated. [. . . ] An ambu-

lance ride and a visit to the hospital are, after all, not

pretty” (wound manager, para. 10). The positive per-

ception of TMed also seems to have increased fur-

ther during COVID-19 as a catalyst due to the in soci-

ety more widespread use of digital applications (spe-

cialist physician, para. 15) and “digitalization is now

more on the agenda” (specialist physician, para. 28).

The interviews even show that TMed is changing the

paramedical profession and empowering them due to

the possibility of delegating medical treatment to non-

physicians (wound manager, para. 35).

Outcomes. TMed has multiple outcomes, as evi-

denced by several interviews. It can be noted that the

use of TMed reduces the fear of contact with tech-

nology in general (nurse, para. 8). The introduction

of TMed has also eliminated General Data Protection

Regulation (GDPR) non-compliant solutions such as

using private devices with private messaging clients

for official purposes like the exchange of wound pic-

tures (NH-Manager, para. 2).

TMed even eliminates waiting and travel times

for vulnerable patients, which improves equality of

opportunity between healthier and multimorbid pa-

tients (NH-Manager, para. 31). According to the GP

(para. 30), efficiencies increase because travel times

are reduced, and physician work time can be bet-

ter used for patients through supportive delegation.

TMed complements current care and can alleviate

some challenges in rural healthcare. TMed allows

physicians to “reduce physician work time per patient

and helps the personal shortage in rural areas” (wound

manager, para. 35). But it is also a relief on the side of

the paramedical staff. In the interview with the medi-

cal assistant (para. 4), it emerged that queries are clar-

ified more quickly through TMed, thus speeding up

the treatment process and making paramedical staff

feel more confident or secure.

Intensive care (para. 31) also states that safety

for patients and caregivers increases because prob-

lems are discussed early, and there is a profes-

sional, uncomplicated possibility of contacting ex-

pertise through TMed. Early preventive interven-

tions, which are possible through TMed, can improve

healthiness: “The patient is fitter, more stable and

can also accept therapy recommendations. I can pre-

vent worsenings and therapists can work with more

resources” (CC-Nurse, para. 16).

Challenges and Barriers. Despite positive attribu-

tions, some barriers, like the mobile network during

home visits, resulted in, as noted by GP (para. 18),

“lost potential.” Participants wanted to use the appli-

cations as often as possible. Still frustratingly, po-

tential use was often seen for the applications, but

the technology couldn’t be used due to cellular cov-

erage. “As an employee, I assume that just works”

(medical assistant, para. 17). The TMed-ECG showed

a preparation effort due to the adhesive electrodes

and, if necessary, shaving of the corresponding ar-

eas, which wasn’t appropriate if the connection failed.

The TMed-ECG was also unwieldy, as shown by the

following testimonial: “Since we have so much med-

ical equipment to carry, the ECG is another suitcase

that has to be lugged” (medical assistance, para. 28).

Furthermore, structural difficulties are apparent,

as expressed in the interview of the NH-Manager and

the GP. The following quote from the NH-Manager

ICT4AWE 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

22

(para. 46) sums it up well: “The individual sectors are

rather brothers-in-law. Only with a few, I like to go

drinking, and with some others, I’m happy if I only

see them at Christmas, and then I’m allowed to leave

after two hours.” The relationship and design of the

cooperation are challenging because each HSP works

on TMed with its intentions, different revenues, di-

verse interests, and different efforts. This, in some

cases, leads to accusations between HSPs. Further-

more, intersectoral collaboration and process respon-

sibility are challenges. Building relationships takes

time because “everyone is cooking their soup and at

the beginning HSPs aren’t networked” (CC-Nurse,

para. 4). Also, not every HSP of the TMed-network

was able to prescribe. “Ultimately, it is the family

doctor who prescribes” (NH-Manager, para. 25).

Digital prescriptions can’t yet be mapped, and

many things, such as wound rounds, still have to be

done analogically for legal reasons. The interviewees

(GP, para. 43 and the special nurse from the clinic,

para. 18) also complain about the lack of financial in-

centives for TMed and poor billing modalities. In ad-

dition, the GP and the special nurse from the clinic

argue that TMed applications are often “just too ex-

pensive” (wound manager, para. 57) and that this is

“exploited economically, putting small HSPs at a dis-

advantage” (GP, para. 44).

Facilitators. The early integration of all rural HSPs

promotes TMed since treatments can be coordinated

better. TMed deployment is an intersectoral process

where it is important to recognize the motivators of

each HSP (GP, para. 46). TMed requires certain rules,

guidelines, statutes, and adequate privacy and secu-

rity (CC-Nurse, Abs. 18). Furthermore, it’s benefi-

cial if all HSP are “working on the same system with

the same things”, i.e., they have common information

and documentation base like an eHR (GP, para. 46).

In this context, “interfaces are desired” (wound man-

ager, para. 16). TMed solutions must be interopera-

ble, i.e., that TMed can be linked to HSP-software.

The need for TMed and digitalization training is

evident: “[As employee] there is uncertainty in han-

dling that you have to be guided first.” (NH-Manager,

para. 8) A high level of digital competence and aware-

ness is helpful, but, as stated by all interviewees,

many HSPs are less digitally aware. It is important

to sensitize all stakeholders for TMed and take away

their fears because if this doesn’t happen, then “the

TMed won’t be used” (nurse, para. 21). Sometimes

it also requires, as mentioned by the NH-Manager

(para. 30), a good interpersonal understanding, emo-

tional intelligence, and investment in relationships

(with employees, partners, and patients). Also, “a pe-

riod of acclimatization is necessary for everyone, in-

cluding the patients” (NH-Manager, para. 31).

Likewise, it is important to make TMed as handy

and user-friendly as possible. “There are definitely

older people who have little experience with digital

technology and are afraid to use it” (nurse, para. 35).

The interview with the GP and medical assistant

stated that TMed should be just easy to use, also the

effort required to use the ECG, for example, must

be reduced to a minimum TMed acceptance is re-

duced when problems quickly lead to frustration in

the stressful daily care routine (CC-Nurse, para. 38).

This was demonstrated by the disconnection of mo-

bile applications in rural areas. Therefore, technology

must always work, and regular funding is beneficial

for spreading TMed (wound manager, para. 16).

5 DISCUSSION

Subsection 5.1 discussed the methodology and Sub-

section 5.2 compares the findings with related work.

5.1 Method Discussion

We generated a variety of TMed-UCs with technol-

ogy that was state of the art (in 2018) when TMed

wasn’t widespread. The TMed-infrastructure, regu-

lations, and billing were just being introduced (Oden-

daal et al., 2020; Baake and Mitusch, 2021), so during

the project (2018 – 2020), it wasn’t possible to com-

pensate the HSP for their TMed-connections. The

UCs were carried out in rural Lower Bavaria. This

region was chosen due to the challenging HSP situa-

tion with a high average age and low population den-

sity. (Bayerisches Landesamt f

¨

ur Statistik, 2019b).

Furthermore, the number of cases is restricted in

each UC (N = 240 applications) because of limited

HSPs in rural areas. This doesn’t allow multivari-

ate analysis. Another shortcoming is that no teleme-

try data could be analyzed. To reduce limitations,

a mixed-method approach, consisting of quantitative

surveys and qualitative interviews, was used accord-

ing to (Kuckartz, 2014). It allowed exploring the sub-

jective perception of TMed users.

5.2 Results Discussion

Our study draws advantages from testing various UCs

with diverse HSPs rather than focusing on a specific

clinical picture, as is often the case in national stud-

ies (Allner et al., 2019; Barth et al., 2018). Overall

we present a multisided picture about TMed in a rural

german region, limiting our results generalization.

Implementing an Intersectoral Telemedicine Network in Rural Areas: Evaluation from the Point of View of Telemedicine Users

23

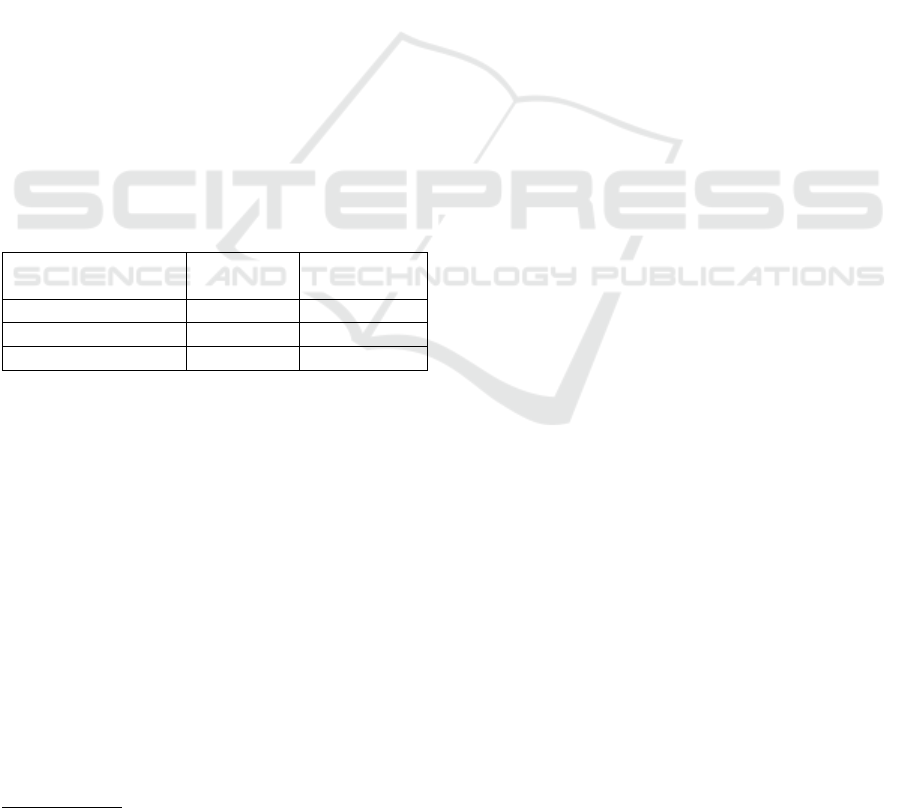

Table 7: Requirements for rural TMed.

Governance Technical HSP-setting

Legal TMed-framework Network coverage Training & Sensitization

Coordination centers Interoperability Wide implementation

Intersectoral incentives Usability & practicability numerous HSPs-variety

Further applied research Frustration- & fault-tolerance Process adaption(s)

In the project, audiovisual communication was

used extensively in the GPs and intensive care. In

the GP, digital support took place in 14.8% (n = 170)

of all 1.147 home visits. In our study, 20% (n = 15)

furthermore of all 75 intensive care treatments TMed

were successfully supported by digital tuning ventila-

tion parameters. This field completes the current re-

search, as no corresponding studies exist in rural ar-

eas with TMed-intensive care. The numbers would

be higher if there weren’t connection losses and more

project HSPs.

GP and intensive care rated TMed qualitatively

as valuable for rural areas. This HSPs may be over-

represented and at bias risk. Other applications, such

as vital data transmission and the eHR, were used

less (Table 4). The used TMed-vital data transmis-

sion needs preparation time (i.e., positioning the elec-

trodes), which doesn’t seem practical enough. In ad-

dition, the commercial eHR wasn’t used much de-

spite a lot of promotion and education. The interviews

show indications that the benefits aren’t seen and that,

at the time of the project, only a few HSPs could use

the eHR.

Some of our results are shown in previous stud-

ies, like the importance of interference-free applica-

tions and infrastructure, esp. mobile networks, as a

substantial barrier in rural Areas (Peine et al., 2020;

Odendaal et al., 2020). Usability, interoperability, re-

liable TMed, and training of HCWs for TMed are

confirmed as important for TMed-deployment (Ya-

mano et al., 2022; Haleem et al., 2021; S¸ ahin et al.,

2021). Some construction sites still exist, such as reg-

ulation and incentivizing funding of TMed, confirmed

by our study (von Solodkoff et al., 2020). In Comple-

menting the Cochrane review (Odendaal et al., 2020),

which argues that fears need to be reduced, our study

results go beyond this and call for awareness raising

and general training in digitization among HCWs and

the population at large. It should be considered that

the socio-cultural environment can play a role in the

TMed-deployment.

The perception of TMeds in our study was positive

in the sense of a high acceptance observed in related

work (Muehlensiepen et al., 2021; Kirchberg et al.,

2020). TMed-benefits can be transferred to rural ar-

eas (Hackmann and Moog, 2010). The avoidance of

travel time, the reduction of burden on the elderly, and

the immediate adjustment of care by TMed are appre-

ciated by HCWs and patients. GPs work time can be

better utilized due to reducing traveling. These bene-

fits and increased quality of life are supported by na-

tional studies (Black et al., 2011; Kn

¨

orr et al., 2022;

Beckers and Stellmacher, 2021). Promoting further

research about TMed in rural areas is necessary. The

study populations are mostly restricted.

6 CONCLUSION

This paper outlines the multidimensional benefits of

TMed in rural german healthcare. It shows the po-

tential of multisided TMed applications due to an in-

tersectoral TMed network with several HSPs. Due to

a mixed-method approach, we evaluated the barriers,

facilitators, and perspectives of TMed users.

Summary. Audio-visual communication was heav-

ily used in the GP (n = 203). Vital-data transmis-

sion was used less for the mountain accident (n = 6)

and also small in GP (n = 11), because of the needed

preparation effort. The eHR was used only in a few

cases (n = 10) as insufficient patients signed up. Al-

though the cases were limited in total (N = 240), qual-

itatively, we highlight that professional users are open

to TMed and satisfied with it. The empowerment of

the paramedical staff is increased, esp. with audio-

visual communication, and they feel more confident.

The elimination of travel time led to relief for GPs

and their staff and ease to the outpatient and inpatient

nursing services. TMed led to efficiency, as time-

consuming telephone arrangements or mailings were

avoided. In addition, delegation and TMed guidance

of medical tasks gave paramedical staff new compe-

tencies, which were perceived as enriching. Ambi-

guities could also be clarified more quickly, creating

security. TMed not only avoids unnecessary travel,

TMed also reduces the patient’s burden.

Recommendations. TMed is feasible and helps to

meet rural healthcare needs, as indicated by our study.

TMed has benefits in rural areas, particularly in terms

of time-saving for GP and intensive care. However,

some barriers must be overcome for wider TMed im-

ICT4AWE 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

24

plementation, such as better mobile network cover-

age in remote areas and financial incentives to collab-

orate intersectoral (Table 7). TMed must be mostly

fail-safe. Furthermore, someone should always be

available to act as a coordinating point and take care.

Coordination centers should be established, monetary

incentives for intersectoral cooperation and TMed

should be given, and a wide range of HSP should

be involved. Other considerations include coordina-

tion and adaptation of the treatment processes among

HSPs and digitalization training for TMed users.

Future research should focus on improving the us-

ability of TMed, exploring TMed barriers, and inte-

grating new technologies like Artificial intelligence

(AI) and augmented reality. More studies should also

conduct knowledge about rural TMed and use bigger

study populations and comparison groups.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was funded by the Bavarian State Min-

istry of Health and Care.

REFERENCES

Allner, R., Wilfling, D., Kidholm, K., and Steinh

¨

auser,

J. (2019). Telemedizinprojekte im l

¨

andlichen Raum

Deutschlands. Eine systematische Bewertung mit dem

”Modell zur Evaluation von telemedizinischen An-

wendungen”. Zeitschrift f

¨

ur Evidenz, Fortbildung und

Qualit

¨

at im Gesundheitswesen, 141-142:89–95.

Amatya, R., Mishra, K., Karki, K., Puri, I., Gautam, A.,

Thapa, S., Katwal, U., Veer, S., Zervos, J., Kaljee, L.,

Prentiss, T., Zenlea, K., Maki, G., Rayamajhi, P. J.,

Khanal, N. K., Thapa, P., Upadhyaya, M. K., and Ba-

jracharya, D. (2022). Post-implementation Review

of the Himalaya Home Care Project for Home Iso-

lated COVID-19 Patients in Nepal. Frontiers in public

health, 10:891611.

Baake, P. and Mitusch, K. (2021). Mobile Phone Net-

work Expansion in Sparsely Populated Regions in

Germany: Roaming Benefits Consumers.

Banbury, A., Nancarrow, S., Dart, J., Gray, L., and Parkin-

son, L. (2018). Telehealth Interventions Delivering

Home-based Support Group Videoconferencing: Sys-

tematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Re-

search, 20(2):e25.

Barth, J., Nickel, F., and Kolominsky-Rabas, P. L. (2018).

Diagnosis of cognitive decline and dementia in rural

areas - A scoping review. International journal of

geriatric psychiatry, 33(3):459–474.

Batsis, J. A., DiMilia, P. R., Seo, L. M., Fortuna, K. L.,

Kennedy, M. A., Blunt, H. B., Bagley, P. J., Brooks,

J., Brooks, E., Kim, S. Y., Masutani, R. K., Bruce,

M. L., and Bartels, S. J. (2019). Effectiveness of Am-

bulatory Telemedicine Care in Older Adults: A Sys-

tematic Review. Journal of the American Geriatrics

Society, 67(8):1737–1749.

Bayerisches Landesamt f

¨

ur Statistik (2019a).

Demographie-Spiegel f

¨

ur Bayern: Berechnungen

bis 2031.

Bayerisches Landesamt f

¨

ur Statistik (2019b). Landkreis

Freyung-Grafenau: Eine Auswahl wichtiger statistis-

cher Daten.

Beckers, R. and Stellmacher, L. (2021). Qualit

¨

atssicherung

in der Telemedizin. In Telemedizin, pages 53–71.

Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Black, A. D., Car, J., Pagliari, C., Anandan, C., Cresswell,

K., Bokun, T., McKinstry, B., Procter, R., Majeed,

A., and Sheikh, A. (2011). The impact of eHealth

on the quality and safety of health care: a systematic

overview. PLoS medicine, 8(1):e1000387.

Bohnet-Joschko, S. and Stahl, T. (2019). Telegeriatrische

Modelle: Einblick in die Zukunft der Versorgung.

Pflegezeitschrift, 72(1-2):50–53.

Butzner, M. and Cuffee, Y. (2021). Telehealth Interven-

tions and Outcomes Across Rural Communities in the

United States: Narrative Review. Journal of Medical

Internet Research, 23(8):e29575.

Dudel, C. (2018). Demografie. In Voigt, R., editor,

Handbuch Staat, Handbuch, pages 7–15. Springer VS,

Wiesbaden, Germany.

Eber, E. L., Arzberger, E., Michor, C., Hofmann-Wellenhof,

R., and Salmhofer, W. (2019). Mobile Teledermatolo-

gie in der Behandlung chronischer Ulzera. Der Hau-

tarzt; Zeitschrift fur Dermatologie, Venerologie, und

verwandte Gebiete, 70(5):346–353.

European Parliament (2021). Demographic outlook for the

European Unii 2021. Publications Office, Brussels.

Ganapathy, K., Alagappan, D., Rajakumar, H., Dhana-

pal, B., Rama Subbu, G., Nukala, L., Premanand,

S., Veerla, K. M., Kumar, S., and Thaploo, V.

(2019). Tele-Emergency Services in the Himalayas.

Telemedicine journal and e-health : the official

journal of the American Telemedicine Association,

25(5):380–390.

Gensorowsky, D., D

¨

orries, M., and Greiner, W. (2021).

Telemedizin – Bewertung des Nutzens. In Marx,

G., Rossaint, R., and Marx, N., editors, Telemedizin,

pages 483–496. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin,

Heidelberg.

Goharinejad, S., Hajesmaeel-Gohari, S., Jannati, N., Go-

harinejad, S., and Bahaadinbeigy, K. (2021). Review

of Systematic Reviews in the Field of Telemedicine.

Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran,

35:184.

Grohs, B. and Thiess, M. (1997). Telematik im Gesund-

heitswesen: Perspektiven der Telemedizin in Deutsch-

land.

Hackmann, T. and Moog, S. (2010). Pflege im Span-

nungsfeld von Angebot und Nachfrage. Zeitschrift f

¨

ur

Sozialreform, 56(1):113–138.

Haleem, A., Javaid, M., Singh, R. P., and Suman, R.

(2021). Telemedicine for healthcare: Capabilities,

Implementing an Intersectoral Telemedicine Network in Rural Areas: Evaluation from the Point of View of Telemedicine Users

25

features, barriers, and applications. Sensors interna-

tional, 2:100117.

Hennig, B. D. (2019). The growth and decline of urban ag-

glomerations in Germany. Environment and Planning

A: Economy and Space, 51(6):1209–1212.

Jedamzik, S. (2022). Bayerische Telemedizin Al-

lianz: Telemedizinische Projekte in Bayern.

https://www.telemedallianz.de/praxis/bayerische-

projekte/. Last checked on Sep 31, 2022.

J

¨

unger, M., Arnold, A., and Lutze, S. (2019). Tele-

dermatologie zur notfallmedizinischen Patientenver-

sorgung : Zweijahreserfahrungen mit teledermatolo-

gischer Notfallversorgung. Der Hautarzt, 70(5):324–

328.

Kidholm, K., Ekeland, A. G., Jensen, L. K., Rasmussen, J.,

Pedersen, C. D., Bowes, A., Flottorp, S. A., and Bech,

M. (2012). A model for assessment of telemedicine

applications: mast. International journal of technol-

ogy assessment in health care, 28(1):44–51.

Kirchberg, J., Fritzmann, J., Weitz, J., and Bork, U. (2020).

eHealth Literacy of German Physicians in the Pre-

COVID-19 Era: Questionnaire Study. JMIR mHealth

and uHealth, 8(10):e20099.

Kn

¨

orr, V., Dini, L., Gunkel, S., Hoffmann, J., Mause, L.,

Ohnh

¨

auser, T., St

¨

ocker, A., and Scholten, N. (2022).

Use of telemedicine in the outpatient sector during

the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey of

German physicians. BMC Primary Care, 23(1):92.

K

¨

ohnen, M., Dirmaier, J., and H

¨

arter, M. (2019).

Potenziale und Herausforderungen von E-Mental-

Health-Interventionen in der Versorgung psychischer

St

¨

orungen. Fortschritte der Neurologie-Psychiatrie,

87(3):160–164.

Kopetsch, T. (2010). Dem deutschen Gesundheitswe-

sen gehen die

¨

Arzte aus! Studie zur Altersstruktur-

und Arztzahlentwicklung. Bundes

¨

arztekammer und

Kassen

¨

arztliche Bundesvereinigung, Berlin, 5. aktu-

alisierte und komplett

¨

uberarb. aufl. edition.

Kuckartz, U. (2014). Mixed Methods: Methodologie,

Forschungsdesigns und Analyseverfahren. Springer

VS, Wiesbaden.

Laschet, H. (2019).

¨

Arztemangel bereitet weiter Sorgen.

Uro-News, 23(5):51.

L

¨

offler, A., Hoffmann, S., Fischer, S., and Spallek,

J. (2021). Ambulante Haus- und Facharztver-

sorgung im l

¨

andlichen Raum in Deutschland –

Wie stellt sich die Versorgungssituation aus Sicht

¨

alterer Einwohner im Landkreis Oberspreewald-

Lausitz dar? Gesundheitswesen (Bundesverband

der Arzte des Offentlichen Gesundheitsdienstes (Ger-

many)), 83(1):47–52.

Ma, Y., Zhao, C., Zhao, Y., Lu, J., Jiang, H., Cao, Y., and

Xu, Y. (2022). Telemedicine application in patients

with chronic disease: a systematic review and meta-

analysis. BMC medical informatics and decision mak-

ing, 22(1):105.

Mathur, S., Walter, S., Grunwald, I. Q., Helwig, S. A.,

Lesmeister, M., and Fassbender, K. (2019). Improving

Prehospital Stroke Services in Rural and Underserved

Settings With Mobile Stroke Units. Frontiers in neu-

rology, 10:159.

Mayring, P. (2010). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundla-

gen und Techniken. Beltz P

¨

adagogik. Beltz, Wein-

heim, 11., aktualisierte und

¨

uberarb. aufl. edition.

Mbunge, E., Batani, J., Gaobotse, G., and Muchemwa,

B. (2022). Virtual healthcare services and digital

health technologies deployed during coronavirus dis-

ease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in South Africa: a

systematic review. Global health journal (Amsterdam,

Netherlands), 6(2):102–113.

Meyer, N. (2020). Sicherung der medizinischen Ver-

sorgung in l

¨

andlichen Regionen: Eine empirische

Untersuchung im rheinland-pf

¨

alzischen Gillenfeld

und Umgebung, volume Band 2 of Schriften zu

Gesundheits- und Pflegewissenschaften. LIT, Berlin

and M

¨

unster.

Muehlensiepen, F., Knitza, J., Marquardt, W., Engler, J.,

Hueber, A., and Welcker, M. (2021). Acceptance

of Telerheumatology by Rheumatologists and Gen-

eral Practitioners in Germany: Nationwide Cross-

sectional Survey Study. Journal of Medical Internet

Research, 23(3):e23742.

Odendaal, W. A., Anstey Watkins, J., Leon, N., Goudge,

J., Griffiths, F., Tomlinson, M., and Daniels, K.

(2020). Health workers’ perceptions and experi-

ences of using mHealth technologies to deliver pri-

mary healthcare services: a qualitative evidence syn-

thesis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews,

3:CD011942.

Partheym

¨

uller, A., M

¨

uller, C., Schneider, V., and Rashid,

A. (2019). Effekte der telemedizinischen Assistenz

bei haus

¨

arztlichen Hausbesuchen im Projekt MONA.

Peine, A., Paffenholz, P., Martin, L., Dohmen, S., Marx, G.,

and Loosen, S. H. (2020). Telemedicine in Germany

During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Multi-Professional

National Survey. Journal of Medical Internet Re-

search, 22(8):e19745.

S¸ahin, E., Yavuz Veizi, B. G., and Naharci, M. I. (2021).

Telemedicine interventions for older adults: A sys-

tematic review. Journal of telemedicine and telecare,

page 1357633X211058340.

Schwab, T. (2020). Pilotprojekt Telearzt: Gesundheit-

stelematik. KVB Forum, pages 28–29.

Sekhon, H., Sekhon, K., Launay, C., Afililo, M., Inno-

cente, N., Vahia, I., Rej, S., and Beauchet, O. (2021).

Telemedicine and the rural dementia population: A

systematic review. Maturitas, 143:105–114.

Speyer, R., Denman, D., Wilkes-Gillan, S., Chen, Y.-W.,

Bogaardt, H., Kim, J.-H., Heckathorn, D.-E., and

Cordier, R. (2018). Effects of telehealth by allied

health professionals and nurses in rural and remote ar-

eas: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal

of rehabilitation medicine, 50(3):225–235.

Techniker Krankenkasse (2022). Forsa-Umfrage:

Digitalisierung im Gesundheitswesen gefordert.

https://www.tk.de/presse/themen/digitale-

gesundheit/elektronische-

patientenakte/digitalisierung-im-gesundheitswesen-

gefordert-2131956?tkcm=aaus. Last checked on

Sep 29, 2022.

ICT4AWE 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

26

The American Geriatrics Society (2012). Guiding princi-

ples for the care of older adults with multimorbidity:

an approach for clinicians: American Geriatrics So-

ciety Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with

Multimorbidity. Journal of the American Geriatrics

Society, 60(10):E1–E25.

Tsiasioti, C., Behrendt, S., J

¨

urchott, K., and Schwinger, A.

(2020). Pflegebed

¨

urftigkeit in Deutschland. In Ja-

cobs, K., Kuhlmey, A., and Greß, S., editors, Mehr

Personal in der Langzeitpflege - aber woher?, Pflege-

Report, pages 257–311. Springer Berlin Heidelberg,

Berlin, Heidelberg.

Valentijn, P. P., Schepman, S. M., Opheij, W., and Brui-

jnzeels, M. A. (2013). Understanding integrated care:

a comprehensive conceptual framework based on the

integrative functions of primary care. International

journal of integrated care, 13:e010.

van den Berg, N., Meinke, C., and Hoffmann, W.

(2009). M

¨

oglichkeiten und Grenzen der Telemedi-

zin in der Fl

¨

achenversorgung. Der Ophthalmologe

: Zeitschrift der Deutschen Ophthalmologischen

Gesellschaft, 106(9):788–794.

von Solodkoff, M., Strumann, C., and Steinh

¨

auser, J.

(2020). Akzeptanz von versorgungsangeboten zur

ausschließlichen fernbehandlung am beispiel des

telemedizinischen modellprojekts , , docdirekt“: ein

mixed-methods design. Das Gesundheitswesen,

83(03):186–194.

Weingarten, P. and Steinf

¨

uhrer, A. (2020). Daseinsvor-

sorge, gleichwertige Lebensverh

¨

altnisse und l

¨

andliche

R

¨

aume im 21. Jahrhundert. Zeitschrift f

¨

ur Politikwis-

senschaft, 30(4):653–665.

Weißenfeld, M. M., Goetz, K., and Steinh

¨

auser, J. (2021).

Facilitators and barriers for the implementation of

telemedicine from a local government point of view

- a cross-sectional survey in Germany. BMC Health

Services Research, 21(1):919.

Yamano, T., Kotani, K., Kitano, N., Morimoto, J., Emori,

H., Takahata, M., Fujita, S., Wada, T., Ota, S.,

Satogami, K., Kashiwagi, M., Shiono, Y., Kuroi, A.,

Tanimoto, T., and Tanaka, A. (2022). Telecardiology

in Rural Practice: Global Trends. International Jour-

nal of Environmental Research and Public Health,

19(7):4335.

Zhang, A., Wang, J., Wan, X., Zhang, Z., Zhao, S., Guo,

Z., and Wang, C. (2022a). A Meta-Analysis of the Ef-

fectiveness of Telemedicine in Glycemic Management

among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes in Primary Care.

International Journal of Environmental Research and

Public Health, 19(7).

Zhang, Y., Bai, W., Li, R., Du, Y., Sun, R., Li, T.,

Kang, H., Yang, Z., Tang, J., Wang, N., and Liu, H.

(2022b). Cost-Utility Analysis of Screening for Di-

abetic Retinopathy in China. Health Data Science,

2022:1–11.

Implementing an Intersectoral Telemedicine Network in Rural Areas: Evaluation from the Point of View of Telemedicine Users

27