Experimentation in Corporate Entrepreneurship: An Exploratory

Multiple Case Study

Stefano D’Angelo, Antonio Ghezzi, Angelo Cavallo, Andrea Rangone and Salvatore Annunziata

Department of Management, Economics and Industrial Engineering, Politecnico di Milano, Milano, Italy

Keywords: Experimentation, Corporate Entrepreneurship, Organizational Design, Lean Startup, Business Model,

Business Model Innovation, Digital Transformation.

Abstract: Experimentation has become one the most influential approaches to entrepreneurship revolutionizing the way

new businesses are launched and enabling entrepreneurs to test their business model through rigorous

experiments. While there is a growing body of research investigating experimentation in a startup context,

there is no corresponding literature exploring the role of experimentation in corporate entrepreneurship

activities despite the increasing interest in experimentation among managers and the growing practitioner

literature urging incumbent organizations to adopt experimentation. Recently, the ideas developed around

experimentation have been taken up by incumbent organizations, with the promise that this approach can

benefit corporate entrepreneurship activities by accelerating them, reducing resource expenditure, and

increasing the chances of success. This is more relevant in the current context where companies have to face

fast-changing customer needs and market trends, as well as the design of complex value propositions.

Drawing on an exploratory multiple case study, this study explores how experimentation is conducted in

incumbent organizations and used as a tool to support corporate entrepreneurship. Based on the findings of

this study, we provide contributions to research and practice on experimentation in corporate entrepreneurship.

1 INTRODUCTION

The use of experimentation, defined as “an iterative

process to reduce uncertainty, engage stakeholders,

and promote collective learning at a relatively low

cost” (Bocken and Snihur, 2020, p.4), has strongly

rooted in the field of entrepreneurship, becoming one

of the most effective approaches to launch and

develop new businesses (Hampel et al., 2020; Kerr et

al., 2014). Scholars and practitioners have discussed

at length the benefits that entrepreneurs can leverage

by adopting experimentation (Thomke, 2020; Ries,

2011). Recently, the ideas developed around

experimentation have been taken up by incumbent

organizations, with the promise that this approach can

benefit corporate entrepreneurship activities by

accelerating them, reducing resource expenditure,

and increasing the chances of success (Cabral et al.,

2021; Ries, 2017). However, while there is a

consistent body of research on experimentation in

startups (Camuffo et al., 2020), the use of

experimentation as a tool to support corporate

entrepreneurship in incumbent organizations has not

yet been systematically explored, despite the

increasing interest among scholars and practitioners

(Ghezzi, 2020; Mariani et al., 2021; Silva et al., 2020;

Hampel et al., 2020). Therefore, by answering the call

of Hampel and colleagues (2020), this study aims to

investigate how incumbents engage in

experimentation, in terms of antecedents, processes,

and outcomes, to support their corporate

entrepreneurship activities, drawing on an

exploratory multiple case study (Yin, 1984) based on

three incumbent firms operating respectively in the

manufacturing, energy and information technology

sectors. Our multiple case study contributes to

research and practice on experimentation in corporate

entrepreneurship. First, answering to the call of

Hampel et al. (2020), we investigate experimentation

in corporate entrepreneurship in terms of antecedents,

process, and outcomes; second, we provide detailed

empirical evidence about the challenges incumbents

face in using experimentation in corporate

entrepreneurship by illustrating the peculiarities in

conducting experimentation in corporate context;

third, we shed light on the enabling role of digital

technologies for experimentation in incumbent

organizations. Finally, our study offers practical

498

D’Angelo, S., Ghezzi, A., Cavallo, A., Rangone, A. and Annunziata, S.

Experimentation in Corporate Entrepreneurship: An Exploratory Multiple Case Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0011827000003467

In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2023) - Volume 2, pages 498-505

ISBN: 978-989-758-648-4; ISSN: 2184-4992

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

insights for managers and practitioners involved in

experimentation in a corporate context.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Experimentation in

Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship is essentially about experimentation

(Kerr et al., 2014). An experimentation-based

approach to entrepreneurship allows to transform the

fundamental assumptions of a business model into

hypotheses that can be rigorously verified through

experiments (Hampel et al., 2020). Experimentation

has become very popular in startup context, and it is

diffused in incubators and accelerators as a way to

launch and develop and support new business

(Hampel et al., 2020). Literature shows various

experimentation methodologies that are recognized

as successful experimentation approaches for

experimentation in entrepreneurship such as lean

startup (Camuffo et al., 2020; Jocevski et al., 2020;

Ries, 2011), design thinking (Brown, 2009) and agile

development (Beck et al., 2001). Several studies have

documented the benefits of experimentation for

startups, in supporting new businesses development

and enabling the growth and long-term survival of

new ventures (Balocco et al., 2019).

2.2 Experimentation in Corporate

Entrepreneurship

In recent years, experimentation has attracted an

increasing interest also in the corporate context with

the promise to boost corporate entrepreneurship

activities by reducing resource requirements and

increasing success rates of entrepreneurial activities

(Ries, 2017; Ries and Euchner, 2013). The long-term

existence of companies depends on their capacity to

explore and experiment (Cabral et al., 2021), as

experimentation may enable incumbents to overcome

inertia and routines that prevent them to effectively

apply the changes required to survive (Anthony and

Tripsas, 2016). However, despite the relevance of the

topic and the increasing interest among practitioners

and academics (Hampel et al., 2020; Felin et al.,

2019), the use of experimentation as a tool to support

corporate entrepreneurship has not yet been

systematically investigated, and research urges

scholars to address this gap. For instance, Bocken and

Snihur (2020) highlight the necessity to understand

the boundary conditions for experimentation in

incumbent organizations. Lindholm-Dahlstrand et al.

(2019), stress the importance to explicit the system

features that can lead companies to experiment. Other

studies point out the relevance to investigate

experimentation in mature contexts (Silva et al.,

2021) or in not digital contexts (Mariani et al., 2021).

To address this gap, taking the process view

suggested by Hampel et al. (2020), we formulate the

following research question: “How do incumbents

engage in experimentation, in terms of antecedents,

process and outcomes, to foster their corporate

entrepreneurship activities?”. We start from the key

assumption that companies are not large versions of

startups (Chesbrough and Tucci, 2020). In fact,

despite corporate experimentation may present

similar characteristics with traditional

experimentation in new ventures, it may have

peculiar characteristics that deserves dedicated

research.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Cases Selection

This research has been designed as an exploratory

multiple-case study (Yin, 1984) which is particularly

useful to explore emerging topics in their real-life

setting (Eisenhardt, 1989) and to reinforce the process

of generalization of results (Meredith, 1988).

Specifically, we investigated experimentation

antecedents, processes and outcomes of three Italian

companies respectively in the manufacturing, energy

and software sectors. Several reasons led us to choose

these cases. First, the heterogeneity in terms of

sectors since an effective use of experimentation may

depend on the type of industry where the company

operates (Silva et al., 2020). Second, the

heterogeneity in terms of organizational design to

adopt experimentation and which could lead to

different results. Third, we considered companies that

present similar maturity in terms of years of adoption

of experimentation in corporate entrepreneurship, to

avoid comparing companies with different degrees of

maturity for experimentation activities.

3.2 Data Gathering and Data Analysis

In our multiple-case study, data were collected

through multiple sources of information (Yin, 1984).

Semi-structured interviews were the primary source

of information. We conducted 25 semi-structured

interviews (8 for case A, 8 for case B and 9 for case

Experimentation in Corporate Entrepreneurship: An Exploratory Multiple Case Study

499

C) with an average duration of 1 hour. As case studies

rely heavily on the correctness of the information

provided by the interviewees for their validity and

reliability, and these can be enhanced by using

multiple sources or “looking at data in multiple ways”

(Yin, 2003), several secondary sources of evidence

and archival data were also added to supplement the

interview data, including strategic reports, informal

emails and internet pages. The content analysis was

performed according to the procedures of the

Grounded Theory methodology (Glaser and Strauss,

1967). From the informants’ exact words, we defined

a set of first-order concepts iterating between data

collected and relevant literature. Based on these,

second-order concepts were developed and allowed

us to view the data at a higher level of abstraction.

Finally, the second-order themes were grouped into

overarching dimensions representing the antecedents,

process and outcomes of experimentation in

corporate entrepreneurship.

4 FINDINGS

4.1 Experimentation Antecedents

The first area of investigation concerns the

antecedents that lead incumbents to adopt

experimentation in their entrepreneurial activities. In

Company A, operating in the manufacturing industry,

the need to progressively enter new markets and

internationalize, exposed the company to a

completely new customer base. To this end, the

company adopts experimentation as a way to learn

about these new markets. Similarly, in Company B,

operating in the energy industry, the huge

proliferation of digital technologies allows the

company to test new possible configurations that can

be delivered on the market. Moreover, Company B,

pursuing a decarbonization strategy, leverages

experimentation to bring new solutions to the market

faster. Company C, operating in the software

industry, adopts experimentation as an intrinsic

business approach to compete. In this context,

experimentation is essential for the company to stay

competitive.

4.2 Experimentation Process

The second area of investigation is related to the

experimentation process in incumbent organizations.

We focus on three main aspects of the

experimentation process: (i) experimentation phases

and methodologies employed; (ii) the organizational

design adopted for experimentation in incumbent

organizations; (iii) the challenges faced in conducting

experimentation in corporate context. Concerning

experimentation phases and methodologies, we can

observe a convergency in the experimentation phases

and methodologies in conducting experimentation in

corporate context. In the first phase, the “ideation

phase”, a new entrepreneurial idea is generated in its

minimal features with the involvement of internal and

external stakeholders. This phase is typically carried

out by adopting design thinking methodology

(Brown, 2009) to perform many diverging and

converging sessions and generate a business model of

the entrepreneurial idea. In the subsequent “execution

phase”, the business model generated is tested and

validated iteratively with customers up to its

validation, following the guidelines provided by the

lean startup methodology (Ries, 2011). Finally, in the

“implementation phase”, the corporates leverage

agile methodology (Ghezzi and Cavallo, 2020) to

support the more mature development of the business

idea and to build the features of the product through

agile sprints. While we found convergency in the

application of experimentation phases and

methodologies, we find heterogeneity concerning the

organizational design to adopt experimentation in the

corporate context. In Company A, experimentation

activities are mainly carried out in the innovation

department, which is the main responsible for the

entire corporate experimentation process from the

ideation phase up to the industrialization phase. In

Company B, experimentation is conducted in a

separate area isolated from the existing organizational

structure. In this way, the company can realize a

“safe” area for experimentation outside the structural

boundaries of the organization. Finally, Company C,

operating in the software industry, embeds

experimentation at many levels. In particular, the

company uses experimentation at three levels. First,

they experiment with their entire organization on

existing products, involving all the corporate

functions to continuously adjust the products

according to market needs; second, they experiment

to develop new products in the innovation

department, similarly, to company A; and third, they

experiment in a separate structure to find potential

new business opportunities, similarly to company B.

Focusing on experimentation process, the three

incumbents show several challenges in conducting

experimentation in corporate entrepreneurship.

Company A reports cultural friction generated by the

skepticism in accepting the results of experimentation

and implementing the required changes in the

established structures of the company. Company B

ICEIS 2023 - 25th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

500

shows the application and understanding of

experimentation methodologies as one of the main

challenges in conducting experimentation. Moreover,

managers of Company B also point out the difficulty

in measuring the outcomes of experimentation

activities. Finally, Company C faces challenges

regarding the organizational culture and the rigid

processes that may hinder the effective use of

experimentation. Specifically, the organizational

functional structure made difficult the horizontal

communication flows and the mix of competencies

needed to run experimentation activities.

4.3 Experimentation Outcomes

The use of experimentation can lead to different types

of outcomes in corporate entrepreneurship. In

Company A, experimentation is used to support the

launch of new products/services that are incremental

and to establish more efficient production processes.

In Company B, where experimentation is conducted

in a separate structure, experimentation is used to

generate new business lines and corporate spin-offs

also with value propositions distant from the core

business. Company C, where experimentation is

diffused inside the organization, presents a wide

variety of experimentation outcomes such as new

products, new business lines and improved

organizational functioning. Through

experimentation, the company can develop and

spread entrepreneurial competencies associated with

experimentation.

5 DISCUSSION

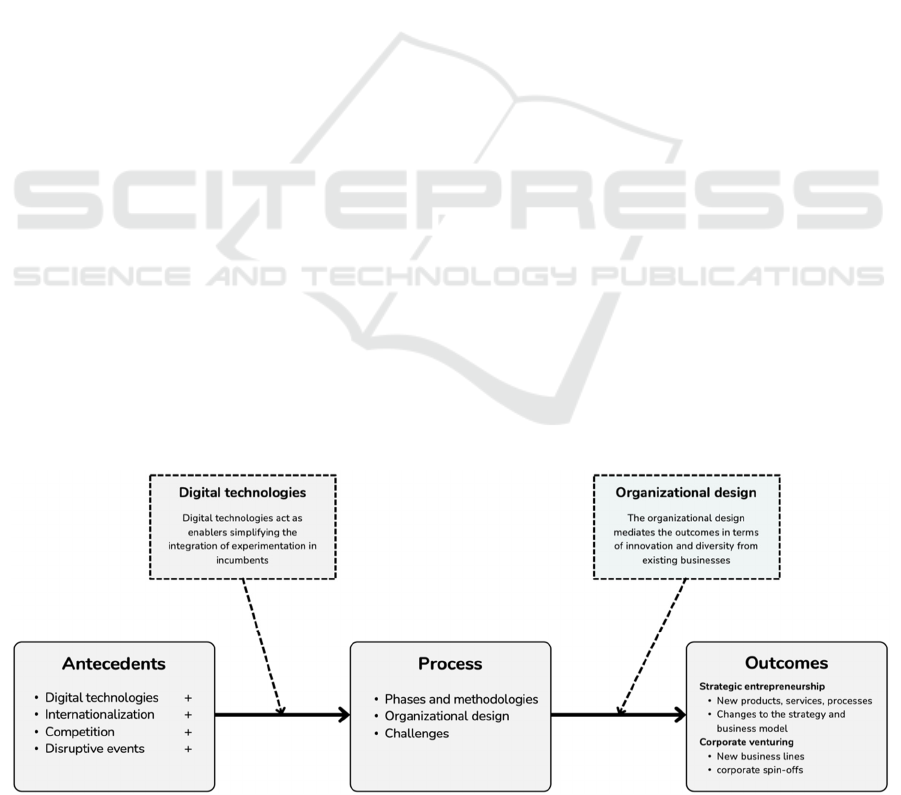

As outcome of our multiple case study, we developed

the conceptual model illustrated in Figure 1 that

illustrates experimentation antecedents, process and

outcome in corporate entrepreneurship.

Experimentation antecedents are the elements that

lead companies to embrace experimentation. Then,

experimentation process in corporate context is

illustrated with its phases and methodologies as well

as the organizational designs adopted, and the

challenges faced. Finally, experimentation outcomes

represent the output in conducting experimentation in

corporate context. In the following sections, we will

discuss in detail each building block of the conceptual

model presented in Figure 1.

5.1 Experimentation Antecedents

Concerning experimentation antecedents, we can

identify four factors that can push incumbents to

adopt experimentation. First, the availability and

proliferation of digital technologies can facilitate

experimentation in scope and scale (Autio et al.,

2018). Second, internationalization is another factor

that can lead incumbents to adopt experimentation.

Entering new countries and markets may imply facing

new cultural contexts that could undermine the

effectiveness of the company's traditional way of

doing business (Cavallo et al., 2020; Chandrashekhar,

2006). Third, competition is another important factor

influencing the adoption of experimentation

(Bohnsack et al., 2019). In our study, experimentation

emerged as a way for incumbents to keep up with an

increasingly dynamic and competitive environment.

Finally, our multiple-case study also confirms the role

of experimentation in response to a disruptive event.

Experimentation in disruptive environments allows

the company to rethink its business model and

implement the necessary changes as shown by

Company C had to completely change its business

model by experimenting in response to the disruptive

Figure 1: Conceptual model for experimentation in corporate entrepreneurship.

Experimentation in Corporate Entrepreneurship: An Exploratory Multiple Case Study

501

phenomenon of decarbonization. Focusing on the role

of digital technologies in corporate experimentation,

our findings show that the proliferation of digital

technologies may force companies to adopt

experimentation, thus acting as an antecedent for

experimentation in corporate context. At the same

time, digital technologies can simplify

experimentation process, therefore also taking the

role of enablers. More specifically, digital

technologies may have three enabling roles for

experimentation in corporate context. First, digital

technologies can enable a greater diffusion of

entrepreneurial competencies within the company. In

this aspect, digital technologies enable a

"democratization of competencies” which can favour

experimentation (Thomke and Euchner, 2020).

Second, digital technologies can make the internal

organizational more flexible and responsive to the

changes required for experimentation. Third, digital

technologies can reduce the number of hierarchical

levels in an organization, thus making the structure

flatter, that is fundamental for conduct

experimentation (Nambisan, 2017).

5.2 Experimentation Process

Concerning experimentation process in corporate

context, we focus on experimentation phases and

methodologies, the possible organizational designs

and the challenges faced.

5.2.1 Experimentation Phases and

Methodologies

Our findings revealed three experimentation phases,

i.e., ideation, execution and implementation. During

the ideation phase, incumbents generate an idea

leveraging on design thinking (Brown, 2009). In the

execution phase, incumbents validate their idea

through the lean startup methodology (Ries, 2011).

Finally, incumbents implement their idea using agile

methodology and agile sprints (Hummel, 2014). This

approach is also confirmed by literature (Shepherd et

al., 2021). Indeed, design thinking provides the

needed empathy and creativity to define a problem

and generate preliminary solutions (Micheli et al.,

2019). Lean startup needs to start from defined

business model assumptions (Silva et al., 2021) to

iteratively test them. Agile sprints can be used to

build the features coming from lean startup

experiments (Harms et al., 2020). Analysing

experimentation phases and methodologies in

corporate context, we observe that incumbents

require more effort in the ideation phase than startups

(Bocken and Snihur, 2020). Indeed, incumbents have

to force themselves to generate and pursue

entrepreneurial ideas that are more natural in startup

context. In addition, incumbents may face higher

difficulties than startups in the implementation phase.

Incumbents have a pre-existing organizational

structure that must accept and integrate the outcomes

of experimentation. This can create cultural frictions

with the existing structures.

5.2.2 Organizational Designs for

Experimentation in Incumbent

Organizations

Another important aspect concerning experimentation

process is related to the choice of the organizational

designs to enable corporate innovation through

experimentation (Hampel et al., 2020). While we

found convergency concerning corporate experimenta-

tion phases and methodologies, incumbents present

heterogeneity in their organizational design to adopt

experimentation. Specifically, we can identify three

types of organizational designs, respectively: (i) a

diffused experimentation approach; (ii) a concentrated

experimentation approach and (iii) a separate

experimentation approach. A diffused experimentation

model refers to a configuration in which experimenta-

tion is pervasive throughout the entire company and

every function is involved in the process. In this type

of configuration, experimentation is conducted

simultaneously and in synergy with the usual daily

activities that the incumbents run. Our multiple case

study shows that this configuration is used to

experiment to innovate existing corporate products

and services. A concentrated experimentation model

implies a configuration where experimentation is

confined in one or few business functions, and

business activities are mostly separate from

experimentation activities. Typically, experimenta-

tion takes place in the most innovative functions, such

as the innovation or product development

departments. Finally, a separate experimentation

model consists in conducting experimentation in a

totally separate structure from the existing

organization. In this case, the company creates a safe

zone where experimentation activities are protected

from organizational antibodies. The three models

proposed, differ for their structural autonomy, which

can be defined as the degree of integration of the

experimentation process with the current processes

and structure of the firm (Sharma and Chrisman,

2007). However, the possible configurations could

vary from totally integrated, as in a diffused model,

to totally separate, as in a separate model.

ICEIS 2023 - 25th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

502

5.2.3 Challenges for Experimentation in

Incumbent Organizations

Our multiple case study show that incumbents may

encounter several challenges in applying

experimentation in corporate context. We identified

three main types of challenges for experimentation in

incumbent organizations, namely: (i)

experimentation-level challenges; (ii) firm-level

challenges and (iii) network-level challenges.

Experimentation-level challenges are the frictions

directly generated by the use of experimentation, such

as how to properly learn experimentation

methodologies, how to specify and apply them in the

corporate context, and how to account for them in

terms of key performances indicators of such

activities. Firm-level challenges are the frictions

generated by the interaction between the

experimentation process and the organization, such as

cultural challenges with the management, the rigid

organizational structures and processes. Network-

level challenges are the frictions generated by the

interaction between the experimentation process and

the stakeholders involved in the experimentation such

as customers and suppliers. Overall, experimentation-

level challenges are common for both incumbents and

startups, as they are intrinsic to the experimentation

methodologies adopted by startups (Ghezzi et al.,

2013; Ghezzi, 2019). On the other side, firm-level and

network-level challenges are specific for incumbents

engaging in experimentation, since incumbents have

a much more structured organization and a much

denser network with respect than startups (Deligianni

et al., 2022). Such challenges highlight the difficulty

in conducting experimentation in corporate context.

However, to mitigate firm-level and network-level

challenges, incumbents can separate experimentation

activities from the existing business activities of the

company. In other words, incumbents can increase

the structural autonomy to experiment, for instance

experimenting in a separate structure, to reduce such

challenges.

5.3 Experimentation Outcomes

Experimentation in corporations may lead to different

outcomes in terms of corporate entrepreneurship

activities depending on the organizational design

used to experiment. The diffused and concentrated

experimentation models can be suitable to launch and

develop new products, improve processes and

competences, as well to renew the existing strategy.

Thus, these experimentation configurations emerged

related to strategic entrepreneurship (Covin and

Miles, 1999), i.e., corporate entrepreneurship domain

that includes a broad array of entrepreneurial

initiatives such as strategic renewal, sustained

regeneration, domain redefinition, organizational

rejuvenation, and business model reconstruction (Hitt

et al., 2001). Indeed, operating with the diffused or

with the concentrated model, innovation outcome

developed is usually incremental in nature. While the

separate model of experimentation is more related to

corporate venturing activities (Sharma and Chrisman,

2007), which refers to the creation of new businesses,

for instance, in the form of new business lines or

corporate spin-offs (Covin and Miles, 1999). Indeed,

operating with a separate experimentation model,

incumbents can generate ideas that are radical from

the current businesses of the company. In conclusion,

we could say that the organizational design used to

experiment with incumbents influences the degree of

innovation and diversity of the outcomes. Indeed, the

higher the structural separation for experimentation,

(i.e., structural autonomy) the higher the degree of

innovation and diversity that the experimentation can

generate for corporate innovation.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Based on the findings of this study, we contribute to

research and practice on experimentation in corporate

entrepreneurship. From the theoretical point of view,

this article offers three main contributions to research.

First, this study answers the call of Hampel et al.

(2020), by investigating how experimentation is

conducted in incumbent organizations in terms of

experimentation antecedents, process and outcomes.

Second, this study offers empirical evidence about the

sorts of challenges at different levels of analysis that

incumbent organizations face in using

experimentation in corporate entrepreneurship (i.e.,

experimentation-level challenges; firm-level

challenges and network-level challenges), the tactics

for getting around these challenges, and the limits of

application of experimentation in incumbents, thus

highlighting the peculiarities in conducting

experimentation in corporate context (Chesbrough

and Tucci, 2020). Third, this study shade light on the

role of digital technologies for experimentation in

corporate entrepreneurship (Cavallo et al., 2020;

Arvidsson and Mønsted, 2018). This article also

provides many practical implications for managers

and incumbent organizations willing to adopt

experimentation in their entrepreneurial activities by

illustrating the phases and methodologies to conduct

experimentation in corporate entrepreneurship as

Experimentation in Corporate Entrepreneurship: An Exploratory Multiple Case Study

503

well as the challenges and the suitable organizational

designs for experimentation in corporations.

However, our study is not free from limitations which

are typical of qualitative studies. For these reasons,

further studies, both qualitative and quantitative, are

required to reinforce the findings of our research. For

instance, future research may explore how

experimentation in corporate can be linked both

practically and theoretically with entrepreneurial

structures such as co-working spaces,

experimentation spaces, incubators, and accelerators

(Bergman and McMullen, 2022; Bojovic et al., 2020).

REFERENCES

Anthony, C., & Tripsas, M. (2016). Organizational identity

and innovation. The Oxford handbook of organizational

identity, 1, 417-435.

Autio, E., Nambisan, S., Thomas, L. D., & Wright, M.

(2018). Digital affordances, spatial affordances, and the

genesis of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strategic

Entrepreneurship Journal, 12(1), 72-95.

Arvidsson, V., & Mønsted, T. (2018). Generating

innovation potential: How digital entrepreneurs

conceal, sequence, anchor, and propagate new

technology. the Journal of strategic information

systems, 27(4), 369-383.

Balocco, R., Cavallo, A., Ghezzi, A., & Berbegal-Mirabent,

J. (2019). Lean business models change process in

digital entrepreneurship. Business Process

Management Journal.

Beck, K., Beedle, M., Van Bennekum, A., Cockburn, A.,

Cunningham, W., Fowler, M., and Kern, J. (2001), The

agile manifesto.

Bergman, B. J., & McMullen, J. S. (2022). Helping

entrepreneurs help themselves: A review and relational

research agenda on entrepreneurial support

organizations. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,

46(3), 688-728.

Bocken, N., & Snihur, Y. (2020). Lean Startup and the

business model: Experimenting for novelty and impact.

Long Range Planning, 53(4), 101953.

Bohnsack, R., & Liesner, M. M. (2019). What the hack? A

growth hacking taxonomy and practical applications for

firms. Business horizons, 62(6), 799-818.

Bojovic, N., Sabatier, V., & Coblence, E. (2020). Becoming

through doing: How experimental spaces enable

organizational identity work. Strategic Organization,

18(1), 20-49.

Brown. T. (2009). Change by Design: How Design

Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires

Innovation, Harper Collins.

Cabral, J. J., Francis, B. B., & Kumar, M. S. (2021). The

impact of managerial job security on corporate

entrepreneurship: Evidence from corporate venture

capital programs. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal,

15(1), 28-48.

Camuffo, A., Cordova, A., Gambardella, A., & Spina, C.

(2020). A scientific approach to entrepreneurial

decision making: Evidence from a randomized control

trial. Management Science, 66(2), 564-586.

Cavallo, A., D’Angelo, S., & Ghezzi, A. (2020,

September). Experimentation and Digitalization:

Towards a Brand-New Corporate Entrepreneurship?. In

15th European Conference on Innovation and

Entrepreneurship, ECIE 2020 (Vol. 2020, pp. 163-

169). Academic Conferences and Publishing

International Limited.

Cavallo, A., Ghezzi, A., & Ruales Guzman, B. V. (2020).

Driving internationalization through business model

innovation: Evidences from an AgTech company.

Multinational Business Review, 28(2), 201-220.

Chandrashekhar, G. R. (2006). Examining the impact of

internationalization on competitive dynamics. Asian

Business & Management, 5(3), 399-417.

Chesbrough, H., & Tucci, C. L. (2020). The interplay

between open innovation and lean startup, or, why large

companies are not large versions of startups. Strategic

Management Review, 1(2), 277-303.

Covin, J. G., & Miles, M. P. (1999). Corporate

entrepreneurship and the pursuit of competitive

advantage. Entrepreneurship theory and practice,

23(3), 47-63.

Deligianni, I., Sapouna, P., Voudouris, I., & Lioukas, S.

(2022). An effectual approach to innovation for new

ventures: The role of entrepreneur’s prior start-up

experience. Journal of Small Business Management,

60(1), 146-177.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study

research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–

550.

Felin, T., Gambardella, A., Stern, S., & Zenger, T. (2019).

Lean startup and the business model: experimentation

revisited. Long Range Planning.

Ghezzi, A., Renga, F., & Cortimiglia, M. (2009). Value

networks: scenarios on the mobile content market

configurations. In 2009 Eighth International

Conference on Mobile Business (pp. 35-40). IEEE.

Ghezzi, A. (2012), Emerging business models and

strategies for mobile platform providers: a reference

framework, info, 14(5), 36-56.

Ghezzi, A. (2019). Digital startups and the adoption and

implementation of Lean Startup Approaches:

Effectuation, Bricolage and Opportunity Creation in

practice. Technological Forecasting and Social

Change, 146, 945-960.

Ghezzi, A. (2020). How Entrepreneurs make sense of Lean

Startup Approaches: Business Models as cognitive

lenses to generate fast and frugal Heuristics.

Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 161,

120324.

Ghezzi, A., & Cavallo, A. (2020). Agile business model

innovation in digital entrepreneurship: Lean startup

approaches. Journal of business research, 110, 519-

537.

Ghezzi, A., Rangone, A., & Balocco, R. (2013).

Technology diffusion theory revisited: a regulation,

ICEIS 2023 - 25th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

504

environment, strategy, technology model for

technology activation analysis of mobile ICT.

Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 25(10),

1223-1249.

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). Grounded theory: The

discovery of grounded theory. Sociology the Journal of

the British Sociological Association, 12, 27–49.

Hampel, C., Perkmann, M., & Phillips, N. (2020). Beyond

the lean start-up: experimentation in corporate

entrepreneurship and innovation. Innovation, 22(1), 1-

11.

Harms, R., & Schwery, M. (2020). Lean startup:

operationalizing lean startup capability and testing its

performance implications. Journal of small business

management, 58(1), 200-223.

Hitt, M. A., Ireland, R. D., Camp, S. M., & Sexton, D. L.

(2001). Strategic entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurial

strategies for wealth creation. Strategic management

journal, 22(6‐7), 479-491.

Hummel, M. (2014, January). State-of-the-art: A systematic

literature review on agile information systems

development. In 2014 47th Hawaii International

Conference on System Sciences (pp. 4712-4721). IEEE.

Jocevski, M., Arvidsson, N., & Ghezzi, A. (2020),

Interconnected business models: present debates and

future agenda, Journal of Business & Industrial

Marketing, 35(6), 1051-1067.

Kerr, W. R., Nanda, R., & Rhodes-Kropf, M. (2014).

Entrepreneurship as experimentation. Journal of

Economic Perspectives, 28(3), 25–48.

Lindholm-Dahlstrand, Å., Andersson, M., & Carlsson, B.

(2019). Entrepreneurial experimentation: a key

function in systems of innovation. Small Business

Economics, 53(3), 591-610.

Mariani, M. M., & Nambisan, S. (2021). Innovation

analytics and digital innovation experimentation: the

rise of research-driven online review platforms.

Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 172,

121009.

Meredith, J. (1998). Building operations management

theory through case and field research. Journal of

Operations Management, 16(4), 441–454.

Micheli, P., Wilner, S.J.S., Bhatti, S.H., Mura, M. and

Beverland, M.B. (2019), “Doing design thinking:

conceptual review, synthesis, and research agenda”,

Journal of Product Innovation Management, 36(2),

124-148.

Nambisan, S. (2017). Digital entrepreneurship: Toward a

digital technology perspective of entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 41(6), 1029-

1055.

Ries, E. (2011). The lean startup: How today’s

entrepreneurs use continuous innovation to create

radically successful businesses. New York: Crown

Business.

Ries, E. (2017). The startup way: How modern companies

use entrepreneurial management to transform culture

and drive long-term growth. New York: Currency.

Ries, E., & Euchner, J. (2013). What large companies can

learn from start-ups. Research-Technology

Management, 56(4), 12-16.

Sharma, P., & Chrisman, S. J. J. (2007). Toward a

reconciliation of the definitional issues in the field of

corporate entrepreneurship. In Entrepreneurship (pp.

83- 103). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Shepherd, D. A., & Gruber, M. (2021). The lean startup

framework: Closing the academic–practitioner divide.

Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 45(5), 967-998.

Silva, D. S., Ghezzi, A., de Aguiar, R. B., Cortimiglia, M.

N., & ten Caten, C. S. (2020). Lean Startup, Agile

Methodologies and Customer Development for

business model innovation: A systematic review and

research agenda. International Journal of

Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(4), 595-628.

Silva, D. S., Ghezzi, A., Aguiar, R. B. D., Cortimiglia, M.

N., & ten Caten, C. S. (2021). Lean startup for

opportunity exploitation: adoption constraints and

strategies in technology new ventures. International

Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research,

27(4), 944-969.

Thomke, S., & Euchner, J. (2020). High velocity business

experiments: An interview with Stefan Thomke.

Research-Technology Management, 63(4), 11-16.

Thomke, S. (2020). Building a culture of experimentation.

Harvard Business Review, 98(2), 40-47.

Yin, R. (1984). Case study research. Beverly Hills CA:

Sage.

Yin, R. (2003). K. (2003). Case study research: Design and

methods. 5, Sage Publications, Inc11.

Experimentation in Corporate Entrepreneurship: An Exploratory Multiple Case Study

505