The CommYOUnity Data Project: Exploring Novice Evaluations of

Urban Spaces

Sarah Cooney

1

and Barath Raghavan

2

1

Villanova University, U.S.A.

2

University of Sourthern California

Keywords:

Urban Planning, Photo Elicitation, Co-Creative Tools, Participatory Design, Grassroots Activism, HCI.

Abstract:

This paper presents the CommYOUnity Data project, which was designed to explore how people describe their

urban surrounds. This project is part of a research agenda that aims to develop technological planning tools

that can be used by grassroots community groups in revitalization and repair efforts. The project contains two

parts: a photo-elicitation study called the CommYOUnity Data Site and a follow-up, the CommYOUnity Data

Survey. Through the site we collected 37 images depicting local scenes with associated captions in response

to a prompt asking residents to describe elements of the submitted scene they would like to see improved.

We then followed up with the survey to dig deeper into the difference between description (of the elements

of a scene) and prescription (of changes to be made). By analyzing both the photo submissions and survey

responses we identified a set of themes, which we use to describe a set of possible technological tools for

grassroots urban design.

1 INTRODUCTION

In Seeing Like a State, Scott reminds us that until

the era of the modern nation state, cities were or-

ganic entities designed over time by the people re-

siding in them. However, as nation states sought to

centralize power, they began imposing order from the

top-down to make cities “legible”—imposing their

abstract way of understanding a city on its physical

structure (Scott, 2020). This resulted in the advent of

city “planning,” and the many grid-like cities we see

today are a direct result of this paradigm shift. Today,

this top-down imposition of order is often perpetu-

ated by the implementation of ”smart city” projects

in which citizens have little say (Gooch et al., 2015).

Beyond urban planning, the imposition of top-

down order has permeated nearly every aspect of our

lives. As Costanza-Chock points out in their book

Design Justice, “...design frequently refers to expert

knowledge and practices contained within a partic-

ular set of professionalized fields” (Costanza-Chock,

2020). Design has been commodified and profession-

alized through a particular set of occupations, one of

which is urban planning. Urban planners, designers,

architects, etc... (or perhaps more accurately the local

bureaucracy or private developers that pay them) have

become the gatekeepers of the built environment and

the technologies that facilitate urban life and services.

Despite this imposition of top-down order, and its

associated problems, many theorists argue that design

is a “universal practice in human communities,” po-

sitioning design as something we all engage in daily

(Costanza-Chock, 2020; Hjelm, 2005). With this no-

tion as a premise, the objective of our study is to ex-

amine how to re-democratize design knowledge and

practice that has become commodified, and to sug-

gest ways in which technological tools can be used to

ensure citizens do not get left behind as smart cities

become the norm. To this end, we explore the ba-

sic language used by “non-designers” to describe and

evaluate their physical

1

environments. Reflecting on

this language in relation to urban planning scholarship

we can identify the “knowledge gap” between ordi-

nary citizens and those trained in the field of urban

design, and effectively answer the question: “What

does it mean to think like a designer?” Our aim is to

answer this question on two fronts—1) if we treat ev-

eryone as a designer and 2) if we regard design as a

specialized profession—and to assess the differences

between these points of view. This information can be

1

We use physical instead of urban to reflect the fact that

participants were from a range of places including urban,

suburban, and rural.

Cooney, S. and Raghavan, B.

The CommYOUnity Data Project: Exploring Novice Evaluations of Urban Spaces.

DOI: 10.5220/0011841000003491

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems (SMARTGREENS 2023), pages 15-27

ISBN: 978-989-758-651-4; ISSN: 2184-4968

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

15

used to help the voices of “non-designers” be heard

better during “official” design exercises and projects

as well help them better complete grassroots projects.

This paper engages with these questions from a

human-computer interaction (HCI) lens, using meth-

ods like photo-eliciation, qualitative analysis, and

speculative design. We present the CommYOUnity

Data Project, two exploratory studies designed to un-

derstand how ordinary citizens view their local envi-

ronments and how this differs from the perspective of

trained designers. The main contributions are:

• The CommYOUnity Data Site,a photo elicita-

tion study, which yielded (a) a small dataset of

image-caption pairs from ordinary people describ-

ing their environments and (b) six themes in their

use of language.

• The CommYOUnity Data Survey, which explored

the distinction between describing (an environ-

ment) and prescribing (changes to it), and how

this differs between trained designers and regular

citizens.

• And finally three speculative technologies show-

ing how these insights might be put into practice.

In the rest of this paper, we first review related

work. We then describe the first study—the Com-

mYOUnity Data Site—and discuss relevant themes.

We then describe the follow-up study—the CommY-

OUnity Data Survey—and its relevant themes. We

conclude by discussing three speculative technologies

that put these insights to work.

2 RELATED WORK

Scholars have examined design as a universal activity,

a kind of creative problem solving that we all employ

in everyday settings, but certain kinds of design have

been commodified and professionalized (Costanza-

Chock, 2020). This leads to one of our main ques-

tions. In the words of designer and educator Sara

Ilstedt Hjelm, “...if everything is design and every-

one designs what is then the particular competence of

the practising professional...?” (Hjelm, 2005). In this

section, we explore what it means to be a designer in

this professional, commodified, sense. First we ex-

plore some general conceptions about what it means

to think like a “designer”, then look at the methods

designers use to elicit ideas from people considered

non-designers during participatory-design activities.

The term “Design Thinking” has come to be syn-

onymous with the framework developed by Tom and

David Kelly (founders of the global design firm IDEO

(IDEOU, 2019)). The framework has five steps that

run from deeply understanding a problem to testing a

solution (Dam and Siang, 2020). Its founders position

it as a means of democratizing design:

“It also allows those who aren’t trained as

designers to use creative tools to address a

vast range of challenges...It’s about embrac-

ing simple mindset shifts and tackling prob-

lems from a new direction” (IDEOU, 2019).

The framework has since been adopted by many in-

stitutions for training designers in a wide variety of

fields (Callahan, 2019; Stola, 2018; Tschimmel and

Santos, 2018). However, the framework has been

criticized for the way it simplifies design into an

overly shallow, even empty process. Designer Jon

Kolko writes, “It takes a thoughtful, complex, itera-

tive, and often messy process and dramatically over-

simplifies it in order to make it easily understand-

able” (Kolko, 2018). Kolko and others also criticize

the way that “Design Thinking” has become com-

mercialized, more about selling things than produc-

ing significant social change (Kolko, 2018). While

we feel IDEO’s design thinking model can be a useful

tool, we acknowledge that it can be a limiting frame-

work. In particular, it can be used by outsiders to

abstract away the complex lived experiences of com-

munities and promote an overreliance on “innovative”

technologies (Costanza-Chock, 2020). We believe

this is especially relevant in the age of smart cities.

We take a broader view of “design thinking”, as

the knowledge and processes learned during formal

(or informal) education in design fields. Although the

IDEO framework is taught in many of these fields,

it is just one of many skills and frameworks, and is

certainly not sufficient for becoming an “expert” de-

signer. As Kolko notes,“Students graduate design-

thinking-centric academic programs with the ability

to think about design but without the ability to de-

sign things, and...design has its roots in the creation

of things. Students of design thinking often don’t

have craft skills” (Kolko, 2018). We believe that

this distinction is important as most people uncon-

sciously “think about design” everyday identifying

various problems in their environments and navigat-

ing life around them. However, it is the ability to

act on these problems, shifting the status quo in some

meaningful way, that is important.

Numerous scholars have tried to define design,

particularly in contrast to other fields like science.

Design scholar Stolterman constrasts the two: “very

simplified, there are two ways to deal with reality.

One method “puts apart” reality to understand how it

works, that’s science. The other one “puts together”

things to create changed reality, that’s design”, and

AI pioneer Herbert Simon, “argued that design is

SMARTGREENS 2023 - 12th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

16

about how things ought to be as opposed to science

which studies how things are” (Hjelm, 2005). Some

of the traits attributed to professional designers are,

“the ability to critically judge quality based in aes-

thetical training” (Hjelm, 2005) and a focus on mak-

ing things “as a foundation for engaging with the

world” (Kolko, 2018).

From a technological perspective, HCI scholars

have been engaged in researching design education

for over two decades (Boyarski, 1998; Maldonado

et al., 2006; Waern et al., 2021). In public-facing

fields like urban planning, a key skill designers must

learn is how to elicit feedback from users or publics in

what is called “Participatory design” (PD) (Andrews

et al., 2014; Simonsen and Robertson, 2012).

Scholars and practitioners have developed numer-

ous strategies for PD (Christodoulou et al., 2018;

O’Leary et al., 2021). Some popular methods are:

games and play to create a comfortable environment

and encourage creativity (Gordon et al., 2017; Light

and Akama, 2014); design cards to prompt reflection

on specific issues (Schuler, 2008; Tomlinson et al.,

2021), and storytelling to explore possibilities for the

future (Baumann et al., 2018; Muller et al., 2020).

We briefly dive deeper into the use of storytelling

as it is important later in the paper. Storytelling—

sometimes referred to as speculative fiction or design

fiction (Astrid Mendez Gonzalez et al., 2020; Muller

et al., 2020)—as a participatory method has recently

received a great deal of attention by the PD commu-

nity (Baumann et al., 2018; Fu et al., 2018; Wang

et al., 2018). In urban planning, sharing stories or per-

sonal reflections is often easier for people than artic-

ulating specific changes or improvements for a place

(Goldstein et al., 2015; Lowery et al., 2020).

The most traditional form of storytelling for PD is

speculative fiction, where participants come up with

a story about the future in some capacity (Goldstein

et al., 2015). This has become particularly popular

in dealing with grand and often somewhat intangi-

ble issues like climate change. Participants are asked

to imagine “alternative” futures where dominant and

pervasive structures that contribute to climate change

are gone or fundamentally altered, often through the

use of technology (Goldstein et al., 2015; Heitlinger

et al., 2021; Lowery et al., 2020). One major criticism

of this method is that it is usually simply speculative,

not often leading to real change (Soden et al., 2021).

Written fictions are not the only form of partici-

patory storytelling. Another popular media for sto-

rytelling is photos—or a “photovoice” study—which

we return to in Section 3 (O’Leary et al., 2021; Raca-

dio et al., 2014).

Another form of storytelling used in PD is seri-

ous games, or games used for a purpose other than

entertaining (Susi et al., 2007). In this method, the

game’s story or narrative is used to prompt discussion

or reflection from participants. A prime example of

this is Gordon and Schirra’s Participatory Chinatown,

used to encourage public meeting participants to think

about and empathize with the varying socio-economic

situations of people living in their neighborhood and

to help them think beyond themselves when suggest-

ing changes for the neighborhood redevelopment plan

(Gordon and Schirra, 2011).

These storytelling activities, and PD activities

generally, are typically part of a public meeting or

workshop facilitated by a designer. In the urban plan-

ning context, the design team takes the information

elicited through the activities and interprets it to cre-

ate a final design or plan (Simonsen and Robertson,

2012). We return to this idea in Section 5.

3 CommYOUnity DATA SITE

The CommYOUnity Data Site is a photo elicitation

study (Harper, 2002) that ran in the summer of

2020. Participants were asked to provide a photo

and associated caption to show off places in their

communities and to talk about how they could be im-

proved. The photos and captions were collected via

the CommYOUnity Data website, see Figure 1. The

site was built with HTML and a Bootstrap template,

and optimized for mobile use so participants could

upload photos while out in their communities. The

upload button took the users to a form where they

were prompted to upload a photo or video and answer

the following prompt:

“Please give a short description of elements of the

image you’d like to see improved and / or what you

love about the space.”

The prompt was intentionally vague in an attempt

to capture a very general sense of how people think

about their physical environments. Aside from a few

rules for preserving anonymity no additional direction

was given, allowing us to capture unfiltered thoughts

from participants. We wanted to know how people

think about their communities in the day-to-day, not

just when there is a specific focus or project at hand.

The first author posted the site to various social

media sites and mailing lists, using convenience sam-

pling. Submissions were collected from late July to

late August 2020. The result was a total of 40 submis-

The CommYOUnity Data Project: Exploring Novice Evaluations of Urban Spaces

17

Figure 1: The homepage for the CommYOUnity Data Site

Project.

sions—38 photos, 1 video, and 1 corrupt file.

2

Sub-

missions were completely anonymous. The instruc-

tions helped to ensure the photos were also as anony-

mous as possible by asking participants to focus on

public spaces and avoid including identifiable people.

Table 1 provides the five-number summary and mean

for the captions. Most submissions were between 20

and 56 words, which felt sufficient for analysis.

Table 1: The five number summary and mean for the num-

ber of words in the submitted captions.

*This was an outlier; the second largest caption is 90 words.

**Without the outlying maximum, the mean is 38 words.

Minimum 2

1st Quartile 20

Median 38

3rd Quartile 56

Maximum 162*

Mean 42**

During this phase of the project, we also con-

ducted two short interviews with people working

in the urban design field—Samantha Pearson and

Christopher Tallman

3

. The interviewees were asked

about what they believe thinking like a designer

means and how it differs from how people without

formal design training think.

3.1 Evaluation

The captions were evaluated using textual analysis

techniques commonly used in qualitative HCI re-

search (Laws and McLeod, 2004). The first author

conducted the primary analysis, with the second au-

thor available to discuss findings that emerged. Given

the relatively small sample size, coding was done by

hand. The focus was primarily on the text of the cap-

tions, but within the context of its associated photo.

The captions were iteratively coded in random or-

der. The codes were collected and categorized to

2

The dataset is available on request.

3

The interviewees were acquaintances of the authors

who expressed interest in the work and were willing to chat

find broader themes. Six patterns emerged in relation

to how people talked about their local spaces: De-

scription vs. Prescription, Personal Story, Commu-

nity Pride, Beauty of Nature, Problem with No Solu-

tion, and Meta-Problem. Table 2 lists each theme and

the number of instances occurring within the dataset.

(Note a submission can exhibit more than one theme.)

Table 2: The 6 themes that emerged from an analysis of

the images and captions from the CommYOUnity Data Site.

The 3rd column is the number of submissions displaying

each theme—a submission can have multiple themes.

Theme # Instances

1. Description vs. Prescription 18

2. Personal Story 12

3. Community Pride 11

4. Beauty of Nature 10

5. Problem with No Solution 4

6. Meta Problem 4

3.2 Discussion

In this section, we discuss each of themes in Table 2

and provide example submissions to illustrate them.

3.2.1 Description vs. Prescription

Theme: Description vs. Prescription

Figure 2: Crowded beach on a weekend with the ocean

waves crashing. Some people are swimming or playing in

the waves while others sit or stand on the sand. Lots of col-

orful umbrellas catch the eye along with some orange flags.

Beach houses follow the shore all the way to the visible

peninsula in the background with a hint of clouds on top of

it. The beautiful blue sky completes the view.

This was by far the most common theme, illustrated

in Figures 2, and evident in about half of the submis-

sions. These submission provided only a description

of the environment instead of assessing where im-

provements could be made (prescribing changes). As

SMARTGREENS 2023 - 12th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

18

noted in (Costanza-Chock, 2020), design is “a mode

of knowledge production that is...abductive and spec-

ulative.” Meaning designers must, “[p]ut things to-

gether and bring new things into being, dealing in the

process with many variables and constraints,” as well

as envision a future that does not yet exist. However,

after analyzing the submitted captions it was clear that

most ordinary people were not thinking in an abduc-

tive or speculative manner.

Captions ranged in length and descriptiveness.

While the caption for Figure 2 is quite descriptive,

another submission, showing a palm tree-lined stretch

of beach, was simply captioned, ”God’s Beauty.” As

noted, the prompt was: “Please give a short descrip-

tion of elements of the image you’d like to see im-

proved and / or what you love about the space.” It is

possible that folks did not read the prompt fully, tak-

ing in only the part asking for a “short description”.

The distinction between description and prescrip-

tion came up in our conversations with the expert de-

signers as well. Samantha Pearson, a designer with a

background in architecture and planning, noted:

“People without design training tend to stop

at a fairly superficial level in looking at, say,

a barn or a sidewalk, having categorized it

using those words and needing to make room

in their brains for other things. A designer is

more likely to compare both or either to other

examples they have on file, both magnificent

and abject, to make note of materials, condi-

tion, siting, craftsmanship, and extrapolating

further from those to ideas about local culture,

history, and economics” (Pearson, 2020).

Thus, when designing technological tools to help

people without formal training think about improv-

ing their environments, it will be important to build in

guidance to help them go beyond superficial charac-

teristics and engage in thinking in a more abductive

and speculative manner.

Since this theme was evident in about half of the

submission, we followed-up with a secondary study

to explore it in greater detail. The follow-up, the

CommYOUnity Survey, and our findings are explored

in depth in Section 4.

3.2.2 Personal Story

As noted in Section 2, there is a large body of re-

search on the use of storytelling in PD as it is consid-

ered a natural way for people to express their opinions

and ideas. We saw multiple instances of storytelling

and personal reflection in our submissions, confirm-

ing this research. Even though stories were not asked

for, more than a quarter of participants responded in

Theme: Personal Story

Figure 3: I love that this nearby restaurant has a lovely

outdoor pavilion where we have been able to dine during

this pandemic. They have been cautious about observing all

the recommended safety protocols and we usually go mid-

afternoon so it feels very safe. It has been a much appre-

ciated treat to be able to go there, sit in the shade, enjoy a

cool breeze and order anything from a simple to an elabo-

rate meal during a time of so many restrictions.

this form. For example, in Figure 3, the submitter

reflects on the pandemic and the local activities they

enjoyed during this challenging time. This indicated

to us that technological tools could draw on this strat-

egy, guiding users through telling a story and making

sense of it in the context of a proposed project. We

return to this idea in the next two sections.

3.2.3 Community Pride

We were surprised by the amount of community pride

exhibited by participants. More than a quarter of par-

ticipants expressed a form pride in their communities.

Although asked what they loved about their environ-

ments, we had anticipated responses would focus on

the physical environment. Instead, participants of-

ten used their submissions as a means of expressing

a broader pride in their hometowns or communities.

This was particularly true in cases where residents

had come together to revitalize a community space,

as shown by Figure 4. In other cases, participants ex-

pressed community pride by naming the place they

had photographed even though submissions were col-

lected anonymously. For example, one caption simply

named the street and town where the photo was taken.

Naming the specific place where they lived seemed to

signify pride in being from that place.

Despite our surprise at this outpouring of com-

munity pride, it tracks with the literature place at-

tachments, which shows that people often have strong

emotional ties to the places they come from or choose

to live in, particularly in the rural context, which

many of our submissions reflect (Manzo and Devine-

Wright, 2020; Wuthnow, 2019).

In designing technology to help people improve

their environments, we might prime them with a re-

minder of their community pride and attachments be-

The CommYOUnity Data Project: Exploring Novice Evaluations of Urban Spaces

19

Theme: Community Pride

Figure 4: This is the playground at the [TOWN NAME]

Village Green. The park started to fall into disrepair a few

years ago but a new Village Green association of locals have

organized to keep things up. This just got fresh mulch.

fore bringing up problems and improvements. As de-

sign expert Christopher Tallman said in our interview,

“asset mapping” within a community can be as impor-

tant as identifying areas for improvement (Tallman,

2020). We discuss this theme further in Section 4.

3.2.4 Beauty of Nature

Theme: Beauty of Nature

Figure 5: Here is the park on an overcast morning. It would

be nice to see more people using this beautiful space.

About a quarter of participants referenced the beauty

of nature by using words like “beauty,” “peace,” and

“calm.” Figure 5 shows an example. In retrospect, this

pattern is not surprising, as the positive benefits of ac-

cess to nature has been widely studied (Mensah et al.,

2016). Green space access has been shown to posi-

tively effect mental health (South et al., 2018), par-

ticularly during the Covid-19 pandemic, with many

cities working to increase opportunities for outdoor

recreation (Solomon, 2020; Surico, 2020). Increas-

ing green space through the cleanup of abandoned lots

(Poon, 2018) or tree planting efforts (Austin and Ka-

plan, 2003) are also some of the simplest urban re-

newal projects to execute.

It is instructive to know that people seem to in-

stinctively understand the benefits of nature. In a tech-

nological tool, we might use this understanding as an

“ice breaker” , a first category of suggestion to help

users to trust a system and its subsequent ideas.

3.2.5 Problem with no Solution

Related to theme one, even when participants did

identify problems they did not always suggest solu-

tions. Our expert Samantha Pearson noted that this is

also a common issue in PD workshops:

“Even when people show up for a commu-

nity charrette or design workshop, a place

where the entire point is envisioning a new

world, it’s like pulling teeth to get them to

draw anything... The really strange part is

that even people who have decided they want

major change often have a hard time propos-

ing anything concrete at all” (Pearson, 2020).

We imagine technological aids could help people

not only identify problems, but also suggest solutions.

For example, in Figure 6, we can imagine a tool sug-

gesting options to get rid of the rocks like paving over

this area or landscaping it.

Theme: Problem with No Solution

Figure 6: For people riding their bikes down from our stu-

dent center, the new rock field looks like a disaster waiting

to happen!

3.2.6 Meta-Problem

Finally, a few of the submissions discussed what we

call meta-problems, going beyond what is shown in

the submitted image. For instance, Figure 7 dis-

cusses the issue of rural transportation access. As

Eric Klinenberg points out in Palaces for the Peo-

ple, the physical aspects of places can have a pro-

found effect on the well-being and resilience com-

munities (Klinenberg, 2018). A good designer helps

people see these connections and can suggest phys-

ical changes based on these meta-problems. For in-

stance, they can connect the health benefits of access

to green space (South et al., 2018) with the desire to

create more pockets of space preserving nature, or un-

derstand how current racial injustice is connected to a

history of racist zoning codes and building decisions,

and then try to ensure suggested changes do not per-

petuate these harms (Rothstein, 2017). This kind of

meta-reasoning will likely be challenging to imple-

ment with technology as meta-reasoning is an open

SMARTGREENS 2023 - 12th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

20

Theme: Meta-Problems

Figure 7: I live in a rural area. There are very few busi-

nesses around me, but I’m okay with that because I enjoy

the wide open space and the benefits of living in the quiet

countryside. Transportation can be problematic where I live

if you don’t own a car. I like that it’s spacious, safe, clean,

and picturesque. The sunsets are beautiful, and the stars can

be easily seen at night. It is a nice place to live, and there

are not many improvements I would recommend making.

problem in artificial intelligence (Peng, 2021).

4 CommYOUnity DATA SURVEY

The CommYOUnity Data Survey was our follow-up

to the CommYOUnity Data Site, designed to explore

the theme of participants describing their environ-

ments without prescribing any changes. We took six

of the images submitted to the site and created a sur-

vey to tease apart the distinction between describing

and prescribing changes. Table 3 shows the six im-

ages used in the survey, which consisted of two ques-

tions for each image:

1. Describe what you see in the scene above.

2. What changes would you make to improve the

space shown in the above image?

Each participant was randomly assigned two of the

six images in random order.

We targeted both laypeople and people with edu-

cational training or work experience in urban design

or architecture. It is possible the laypeople had train-

ing in another type of design, but we do not know

as the data was collected anonymously. The 325 lay

responses were collected via convenience sampling

from the first author’s social media network. The 24

expert responses came from students and professors

in the schools of architecture and public policy at a

large private university. Table 4 shows the number of

responses collected per image.

4.1 Evaluation

We coded the responses similarly to the captions from

the CommYOUnity Data Site. The first author did

the primary coding and thematic analysis, while the

second author was available to discuss themes. The

expert responses were evaluated first. We coded the

answers keeping in mind the context of the associ-

ated image, and paid particular attention to things that

might signify design expertise. Due to the small sam-

ple size, the responses were hand coded.

We then coded the novice responses, paying atten-

tion to the themes from the expert responses as well

as looking for new codes and themes. We also looked

at the responses in the context of the themes from the

Community Data Site. Given the volume of novice

responses, we used the Atlas.ti software for coding

4

.

The result was 74 unique codes. (Codes can be made

available upon request.) We now discuss the insights

gained from this analysis.

4.2 Discussion

In this section we discuss: similarities and differences

between the expert and novice responses, themes

from the site that re-emerged in the survey, and fi-

nally, a few themes that emerged solely in the survey.

4.2.1 Expert vs. Novice

Commonalities. There was a subset of suggestions

common to both experts and novices, including sug-

gestions to add different kinds of landscaping to some

of the scenes. In fact, improvements to the land-

scape in various forms was the most common code for

novice responses. Both novice and expert respondents

also suggested burying the utility lines in Images 2

and 3, and also suggested fixing cracks in the road

visible in several images. In general, these common

suggestions dealt with more obvious cosmetic fixes,

or surface level changes, things that are fairly easy to

notice and do not require a specialized vocabulary to

discuss.

Differences. The experts included what we call “ur-

banism trends.” For instance, several of the experts

mentioned “porous surfaces” when discussing fixing

roads and sidewalks, a growing trend in areas where

water scarcity and retention are problems (Razzagh-

manesh and Borst, 2019). Another respondent wrote

about innovative solutions for road repair, noting they

would like to, “try some solutions that are being used

in other parts of the world. I would like to try out a

4

http://atlasti.com/

The CommYOUnity Data Project: Exploring Novice Evaluations of Urban Spaces

21

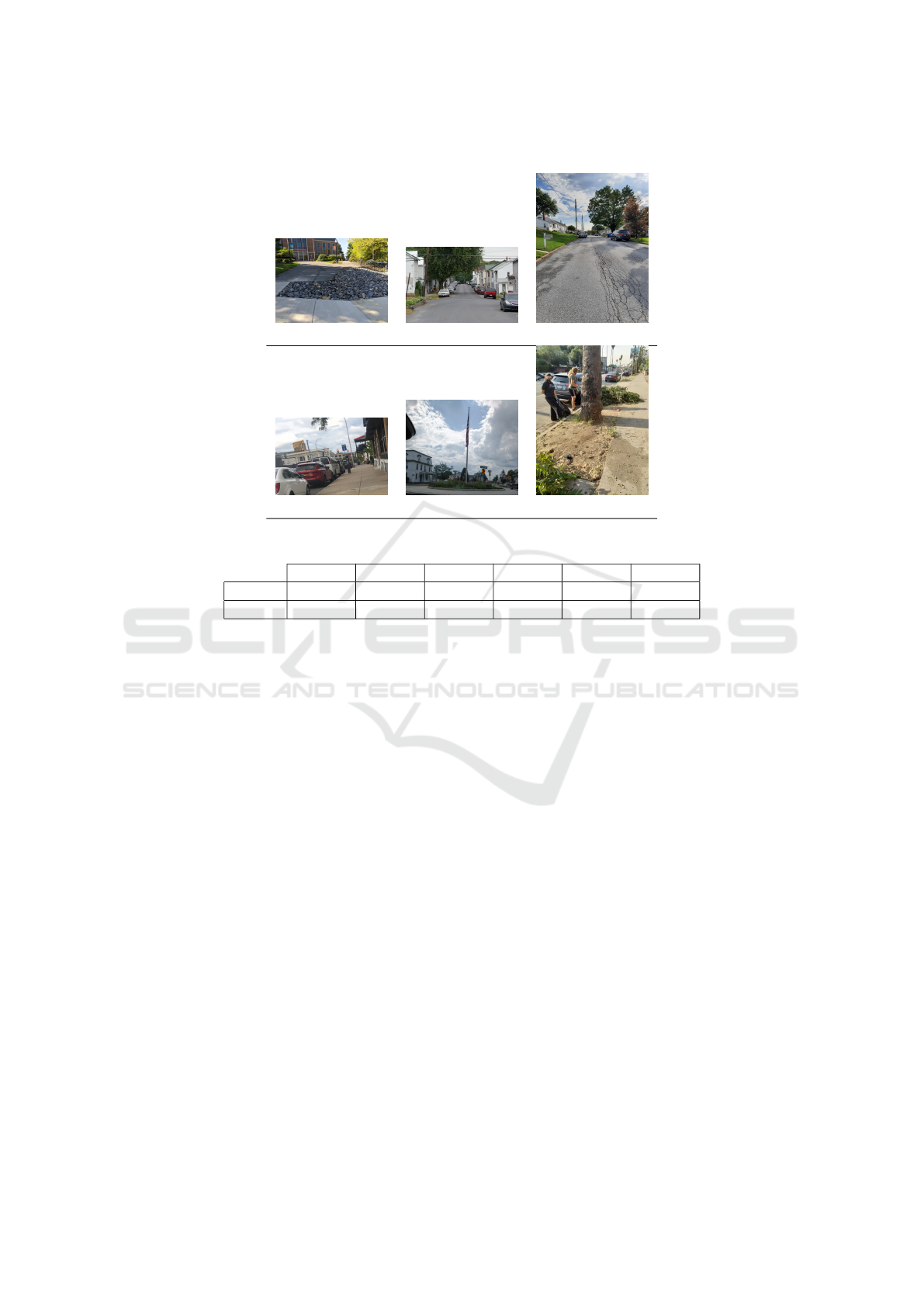

Table 3: Six images submitted to the CommYOUnity Site Project that were included in the Survey Project.

Image 1 Image 2 Image 3

Image 4 Image 5 Image 6

Table 4: The number of survey responses per image broken down by Novice and Expert respondents.

Image 1 Image 2 Image 3 Image 4 Image 5 Image 6

Novice 111 117 118 101 90 109

Expert 8 6 9 8 10 7

road made from waste plastic or rubber if feasible.”

While the novices suggested a variety of good im-

provements, there are industry trends which may not

be well-known to outsiders. Thus it may be helpful

to have technological tools that are “aware” of these

trends and best practices and that can present them to

laypeople in a way that is accessible to help stretch

their imaginations regarding what is possible.

Another major difference was the need for con-

text. Many of the experts asked implicitly or explic-

itly about the context for the improvements. For in-

stance, one expert implicitly referred to the design

context when making the following list of suggestions

for Image 1 by noting that the suggestions depended

on the use case (italics added for emphasis):

• variety of plants / materials in stone area (assum-

ing use is water retention)

• narrower and more permeable sidewalk

• benches or gathering space (if heavy pedestrian

area)

• Additional shading (depending on climate)

• More engagement between facade of building and

sidewalk (if main entrance to building)

When presented with Image 6, another expert re-

sponded, “I don’t understand this question. Because

without a clear purpose there won’t be a so-called de-

sign.” In contrast only 6 of 325 novices noted the con-

text. For two, it was through reference to the “home-

owners” or “those who live there”, perhaps mirroring

their own concerns as citizens.

Our key takeaway was that community members

are embedded in the day-to-day trappings of a neigh-

borhood or environment, and it is important to think

about how to capture this knowledge outside of a par-

ticular project. As Samantha Pearson said, when res-

idents are presented with a specific proposal it is of-

ten difficult to get them to articulate their thoughts or

ideas (Pearson, 2020). However, we know that they

have valuable insights from their lived experiences.

The question is how to capture these insights when a

specific “designerly” context is at hand. This is an is-

sue we hope could be solved with technological tools

like those suggested in Section 5.

4.2.2 Reemerging Themes

We found that several themes from the Site study

reappeared in the survey responses.

Reflecting both the first theme—Description

vs. Prescription—and the fifth—Problem with No

Solution—a number of respondents did not offer any

changes when responding to the second survey ques-

SMARTGREENS 2023 - 12th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

22

tion. The question was mandatory, but included re-

sponses like “nothing” or “none”. While some of re-

spondents offered justification (i.e., P147 “Nothing.

It’s clean. Nice, wide sidewalks.”) most did not. It

was not always true that this was a default response.

Only 4 of the 35 respondents who offered no sug-

gestion did so for both images they saw. The other

31 offered suggestions for one of the images but not

the other. This finding confirmed for us the need for

technological systems to offer guidance to help ex-

tract suggestions from non-designers in cases where

having a trained designer on hand is not feasible.

Two other common themes that emerged were

community pride and storytelling / personal reflec-

tion. Though participants were not speaking about

their own communities in this part of the study, they

nonetheless exhibited their sense of community pride

by referencing imagined communities in the images.

For example, in prescribing changes for Image 3, P80

wrote, “The road surface needs repaired to give the

neighborhood a fresh look and for the community to

feel valued.” In another example, P149 described Im-

age 2 as a “Small town community. This is a road

where neighbors help neighbors.” This again gives

a sense that participants are thinking as community

members and not as objective designers even when

they are not seeing their own communities.

Participants also used stories to, position them-

selves within the scenes. For example, describing Im-

age 3, P42 wrote “A peaceful summer day while tak-

ing my dog for a midday walk.” Of the same image,

P153 similarly said, “I see a nice friendly neighbor-

hood in which I would be taking an evening walk.”

Given that these themes appeared in both studies,

we found them particularly instructive in creating the

speculative technologies.

4.2.3 New Themes

Several other themes emerged from our analysis of

the novice responses. Our respondents were not

trained urban designers, and most made generic sug-

gestions for surface level changes, but some showed

more familiarity with the “official” process. For in-

stance, when suggesting improvements for Image 2,

P40 said:

Traffic study, unless one has recently been

done. Trim trees, if recommended by power

company. Maybe some CDBG funds for hous-

ing improvement projects.

CDBG refers to the Community Development

Block Grant Program from the US Department of

Housing and Urban Development, indicating the par-

ticipant has some knowledge of engineering (traffic

studies) and this grant program, shown by the casual

use of the acronym. Another example is reference

to “ADA” guidelines by two participants (P50 and

P63) when discussing accessibility in Images 2 and

3. P265 used the term “zero scape”, which refers to

landscaping made up of dirt or gravel without plants,

when talking about Image 6. These examples indi-

cate that we should consider the varied levels of expe-

rience users of a technological tool might bring with

them and design accordingly. This tracks with pre-

vious work showing users prefer different levels of

guidance from co-creative tools (Oh et al., 2018).

Similarly, the level of detail offered by partici-

pants also varied. Even without the jargon of urban

planning, some still offered quite detailed improve-

ment plans. For example, about Image 1, P27 wrote:

I would completely uproot the sidewalk and

get rid of all of the chunky rocks. Change the

stairs into a ramp (so it’s wheelchair friendly)

and keep one railing bar (on the right side)

and freshly paint it. I’d then create one fresh

path of sidewalk from the ramp to the entrance

of the building and plant grass everywhere

else. People can walk on the grass...it’s meant

to be walked on. Sidewalk is overrated.

In contrast, of the same image P82 suggested, Add

colorful plants. Overall, responses varied in detail be-

tween these extremes, with most being less detailed.

Another interesting finding was regional language

differences among participants. In particular, the

structure shown in Image 5 was referred to as a

“roundabout”, “round about”, “turn around”, “ro-

tary”, and “traffic circle”. (Incidentally, the first au-

thor uses roundabout while the second author uses

traffic circle.) Thus we need to be aware both of our

own regional language biases as designers, but also

our target user population. We might include visual

cues to ensure a shared understanding or allow users

to build in their own local vocabularies.

5 DISCUSSION

In this section, we use the insights from the two stud-

ies to offer three examples of technologies that could

help ordinary people think about their environments

in the context of neighborhood revitalization.

5.1 Neighborhood Asset Mapping

As we saw in both parts of the study, people seem

to have great pride in where they come from. While

the underlying motivation of most revitalization and

The CommYOUnity Data Project: Exploring Novice Evaluations of Urban Spaces

23

smart city projects is to help people think about prob-

lem areas and solutions, it could be useful to start

by generating a sense of community pride. This can

help users feel a connection to and ownership of their

communities, priming them to want to invest energy

in improvements. In essence, this is the idea behind

asset-based design, a strategy that encourages design-

ers from outside a community to start by looking at

what a it has not what it lacks—looking for assets in-

stead of assuming deficits (Costanza-Chock, 2020).

From a technological standpoint, we can imag-

ine co-opting a tool like CommunityCrit (Mahyar

et al., 2018), which enables citizens to voice their

concerns and opinions about community issues via

crowd-sourcing technology. This kind of system, de-

signed to forward citizen complaints about local is-

sues to city officials or to be assigned to city mainte-

nance crews has been studied in various iterations by

scholars in different parts of the world (Bousios et al.,

2017; Motta et al., 2014).

We imagine a similar system designed to collect

only assets or stories of good in the community. These

submissions could be displayed publicly to remind

citizens that they are proud of their communities. As-

sets could include physical characteristics like beau-

tiful parks, clean streets, or a well stocked public

library, but might also include more intangible ele-

ments like friendly and helpful residents or a sense of

safety and security. By drawing on community pride

and existing assets, we conjecture that people will be

better primed to think about improvements for their

communities when that time comes.

5.2 A Day in the Neighborhood

Storybot

One technique that has lately gained ground in HCI

studies is the use of AI-backed chatbots, particularly

in the context of mental health care (Ahn et al., 2020;

Lee et al., 2020; Yasuda et al., 2021). Since story-

telling emerged from both of our studies as a natu-

ral way for people to speak about their environments

we can imagine a chatbot that asks residents to tell

us a story about a day spent in their neighborhood or

about completing a specific task, and then using the

chatbot to prompt them to think about how their lives

could be made better or easier through environmental

or technological changes. Imagine a resident telling

a story about food shopping and the chatbot prompt-

ing them to think about food access, maybe how they

wish their community had a farmers market. Ideally,

the bot would parse the stories and subsequent inter-

actions into an actionable list of changes or upgrades

that could be used as a starting point for taking action.

5.3 Co-Creative Image Editor

A final tool we imagine is a co-creative image editor.

Co-creative agents are a subset of creativity support

tools—digital tools for supporting users as they com-

plete creative tasks in a variety of fields (Frich et al.,

2019). Co-creative agents include an AI-based agent

that makes suggestions to the user with regard to their

creative output (Karimi et al., 2020; Oh et al., 2018).

We imagine combining photo editing with insights

from our studies into a co-creative tool that lets a

user upload an image of their environment and helps

them make edits based on prompts or ideas from

the agent informed by our insights. For example,

the agent might start by prompting the user to think

about access to green-space or nature, perhaps even

using computer vision to measures its prevalence (i.e.

(Lumnitz et al., 2021)), since adding green space is an

effective way of improving many environments that

is also relatively simple and well received. The agent

might also be imbued with some of latest trends or

best practices in landscape architecture or similar “le-

gitimized” design fields to teach the user about things

like porous surfaces for runoff management or the im-

portance of native plants. We can imagine that the

system would output a professional or photo-realistic

rendering of what the space in question could look

like given the user and agent’s proposed changes.

We could even move beyond two-dimensional

rendering and allow the user to work in three dimen-

sions (Tuite et al., 2011) or view their designs in aug-

mented reality (Ketchell et al., 2019), given recent ad-

vances in lightweight systems for creating 3D models

from only a few images (Meiyappan, 2008).

6 CONCLUSION

This paper introduced the CommYOUnity Data

Project, which uses an HCI lens to think about de-

mocratizing access to design technology. The project

consisted of a photo elicitation study called the Com-

mYOUnity Data Site and a follow-up called the Com-

mYOUnity Data Survey, which allowed us to exam-

ined how “non-designers” talk about their environ-

ments and contrast this with how trained designers

think about the environment. Through a qualitative

analysis of the responses, we identified several themes

to guide the creation of technological tools to help or-

dinary citizens think about improving their communi-

ties. We then suggested three speculative tools based

on these insights—an asset mapping system, a story-

based chatbot, and a co-creative image editor. In fu-

ture work, we hope to explore these speculative sys-

SMARTGREENS 2023 - 12th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

24

tems in more detail by building and testing prototypes

and working with community groups engaged in revi-

talizing their environments.

REFERENCES

Ahn, Y., Zhang, Y., Park, Y., and Lee, J. (2020). A chatbot

solution to chat app problems: Envisioning a chatbot

counseling system for teenage victims of online sexual

exploitation. In Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI

Conference, pages 1–7.

Andrews, B., Bardzell, S., Clement, A., D’Andrea, V.,

Hakken, D., Poderi, G., Simonsen, J., and Teli, M.

(2014). Teaching participatory design. In Proceedings

of the 13th ACM PDC: Short Papers, Industry Cases,

Workshop Descriptions, Doctoral Consortium papers,

and Keynote abstracts-Volume 2, pages 203–204.

Astrid Mendez Gonzalez, P., Casta

˜

neda Mosquera, S., Paula

Bernal Tinjaca, M., Mej

´

ıa Sarmiento, R., Alejandro

Morales Rubio, R., Camilo Giraldo Manrique, J., and

Baquero Lozano, S. (2020). Participatory construc-

tion of futures for the defense of human rights. In Pro-

ceedings of the 16th ACM PDC 2020-Participation (s)

Otherwise-Volume 2, pages 10–16.

Austin, M. E. and Kaplan, R. (2003). Identity, involvement,

and expertise in the inner city: some benefits of tree-

planting projects. Identity and the natural environ-

ment: the psychological significance of nature. MIT

Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, pages 205–

225.

Baumann, K., Caldwell, B., Bar, F., and Stokes, B. (2018).

Participatory design fiction: community storytelling

for speculative urban technologies. In Extended Ab-

stracts of the 2018 CHI Conference, pages 1–1.

Bousios, A., Gavalas, D., and Lambrinos, L. (2017). City-

care: Crowdsourcing daily life issue reports in smart

cities. In 2017 IEEE Symposium on Computers and

Communications (ISCC), pages 266–271. IEEE.

Boyarski, D. (1998). Designing design education. ACM

SIGCHI Bulletin, 30(3):7–10.

Callahan, K. C. (2019). Design thinking in curricula. The

international encyclopedia of art and design educa-

tion, pages 1–6.

Christodoulou, N., Papallas, A., Kostic, Z., and Nacke,

L. E. (2018). Information visualisation, gamification

and immersive technologies in participatory planning.

In Extended Abstracts of the 2018 CHI Conference,

pages 1–4.

Costanza-Chock, S. (2020). Design justice: Community-led

practices to build the worlds we need. The MIT Press.

Dam, R. and Siang, T. (2020). Stages in the design think-

ing process. interaction design foundation. Retrieved

from www. interaction-designing/literature/article/5-

stages-in-thedesign-thinking-process.

Frich, J., MacDonald Vermeulen, L., Remy, C., Biskjaer,

M. M., and Dalsgaard, P. (2019). Mapping the land-

scape of creativity support tools in hci. In Proceedings

of the 2019 CHI Conference, pages 1–18.

Fu, Z., He, J., and Chao, C. (2018). Key elements of de-

sign thinking tools: Learn from storytelling process in

high school student’s workshop. In Proceedings of the

Sixth International Symposium of Chinese CHI, pages

128–131.

Goldstein, B. E., Wessells, A. T., Lejano, R., and Butler, W.

(2015). Narrating resilience: Transforming urban sys-

tems through collaborative storytelling. Urban Stud-

ies, 52(7):1285–1303.

Gooch, D., Wolff, A., Kortuem, G., and Brown, R. (2015).

Reimagining the role of citizens in smart city projects.

In Adjunct Proceedings of the 2015 ACM Interna-

tional Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous

Computing and Proceedings of the 2015 ACM Inter-

national Symposium on Wearable Computers, pages

1587–1594.

Gordon, E., Haas, J., and Michelson, B. (2017). Civic cre-

ativity: Role-playing games in deliberative process.

International Journal of Communication, 11:19.

Gordon, E. and Schirra, S. (2011). Playing with empathy:

digital role-playing games in public meetings. In Pro-

ceedings of the 5th International Conference on Com-

munities and Technologies, pages 179–185.

Harper, D. (2002). Talking about pictures: A case for photo

elicitation. Visual studies, 17(1):13–26.

Heitlinger, S., Houston, L., Taylor, A., and Catlow, R.

(2021). Algorithmic food justice: Co-designing more-

than-human blockchain futures for the food commons.

In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference, pages 1–

17.

Hjelm, S. I. (2005). If everything is design, what then is a

designer? Nordes, (1).

IDEOU (2019). What is design thinking? https://www.

ideou.com/blogs/inspiration/what-is-design-thinking.

Karimi, P., Rezwana, J., Siddiqui, S., Maher, M. L., and

Dehbozorgi, N. (2020). Creative sketching partner: an

analysis of human-ai co-creativity. In Proceedings of

the 25th International Conference on Intelligent User

Interfaces, pages 221–230.

Ketchell, S., Chinthammit, W., and Engelke, U. (2019). Sit-

uated storytelling with slam enabled augmented real-

ity. In The 17th International Conference on Virtual-

Reality Continuum and its Applications in Industry,

pages 1–9.

Klinenberg, E. (2018). Palaces for the people: How social

infrastructure can help fight inequality, polarization,

and the decline of civic life. Crown.

Kolko, J. (2018). The divisiveness of design thinking. In-

teractions, 25(3):28–34.

Laws, K. and McLeod, R. (2004). Case study and grounded

theory: Sharing some alternative qualitative research

methodologies with systems professionals. In Pro-

ceedings of the 22nd international conference of the

systems dynamics society, volume 78, pages 1–25.

Lee, Y.-C., Yamashita, N., Huang, Y., and Fu, W. (2020).

” i hear you, i feel you”: Encouraging deep self-

disclosure through a chatbot. In Proceedings of the

2020 CHI conference, pages 1–12.

Light, A. and Akama, Y. (2014). Structuring future social

relations: the politics of care in participatory prac-

The CommYOUnity Data Project: Exploring Novice Evaluations of Urban Spaces

25

tice. In Proceedings of the 13th ACM PDC: Research

Papers-Volume 1, pages 151–160.

Lowery, B., Dagevos, J., Chuenpagdee, R., and Vodden, K.

(2020). Storytelling for sustainable development in

rural communities: An alternative approach. Sustain-

able Development, 28(6):1813–1826.

Lumnitz, S., Devisscher, T., Mayaud, J. R., Radic, V.,

Coops, N. C., and Griess, V. C. (2021). Mapping trees

along urban street networks with deep learning and

street-level imagery. ISPRS Journal of Photogramme-

try and Remote Sensing, 175:144–157.

Mahyar, N., James, M. R., Ng, M. M., Wu, R. A., and Dow,

S. P. (2018). Communitycrit: Inviting the public to im-

prove and evaluate urban design ideas through micro-

activities. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Confer-

ence, page 195. ACM.

Maldonado, H., Lee, B., and Klemmer, S. (2006). Tech-

nology for design education: a case study. In CHI’06

Extended Abstracts, pages 1067–1072.

Manzo, L. C. and Devine-Wright, P. (2020). Place attach-

ment: Advances in theory, methods and applications.

Routledge.

Meiyappan, S. (2008). Method for fast stereo matching of

images. US Patent App. 11/426,940.

Mensah, C. A., Andres, L., Perera, U., and Roji, A. (2016).

Enhancing quality of life through the lens of green

spaces: A systematic review approach. International

Journal of Wellbeing, 6(1).

Motta, G., You, L., Sacco, D., and Ma, T. (2014). City feed:

A crowdsourcing system for city governance. In 2014

IEEE 8th international symposium on service oriented

system engineering, pages 439–445. IEEE.

Muller, M., Bardzell, J., Cheon, E., Su, N. M., Baumer,

E. P., Fiesler, C., Light, A., and Blythe, M. (2020).

Understanding the past, present, and future of design

fictions. In Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Con-

ference, pages 1–8.

Oh, C., Song, J., Choi, J., Kim, S., Lee, S., and Suh, B.

(2018). I lead, you help but only with enough details:

Understanding user experience of co-creation with ar-

tificial intelligence. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI

Conference, pages 1–13.

O’Leary, T. K., Stowell, E., Hoffman, J. A., Paasche-Orlow,

M., Bickmore, T., and Parker, A. G. (2021). Examin-

ing the intersections of race, religion & community

technologies: A photovoice study. In Proceedings of

the 2021 CHI Conference, pages 1–19.

Pearson, S. (2020). Samantha perason interview.

Peng, H. (2021). A brief survey of associations be-

tween meta-learning and general ai. arXiv preprint

arXiv:2101.04283.

Poon, L. (2018). The healing potential of turning vacant

lots green.

Racadio, R., Rose, E. J., and Kolko, B. E. (2014). Research

at the margin: participatory design and community

based participatory research. In Proceedings of the

13th ACM PDC: Short Papers, Industry Cases, Work-

shop Descriptions, Doctoral Consortium papers, and

Keynote abstracts-Volume 2, pages 49–52.

Razzaghmanesh, M. and Borst, M. (2019). Long-term ef-

fects of three types of permeable pavements on nutri-

ent infiltrate concentrations. Science of the total envi-

ronment, 670:893–901.

Rothstein, R. (2017). The color of law: A forgotten history

of how our government segregated America. Liveright

Publishing.

Schuler, D. (2008). Liberating voices: A pattern language

for communication revolution. MIT Press.

Scott, J. C. (2020). Seeing like a state: How certain schemes

to improve the human condition have failed. Yale Uni-

versity Press.

Simonsen, J. and Robertson, T. (2012). Routledge interna-

tional handbook of participatory design. Routledge.

Soden, R., Pathak, P., and Doggett, O. (2021). What we

speculate about when we speculate about sustainable

hci. In Proceedings of the 4th ACM SIGCAS COM-

PASS Conference.

Solomon, A. (2020). Growing atlanta suburb reclaiming an

unexpected public space.

South, E. C., Hohl, B. C., Kondo, M. C., MacDonald,

J. M., and Branas, C. C. (2018). Effect of greening

vacant land on mental health of community-dwelling

adults: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA network

open, 1(3):e180298–e180298.

Stola, K. (2018). User experience and design thinking as

a global trend in healthcare. Journal of Medical Sci-

ence, 87(1):28–33.

Surico, J. (2020). Need more outdoor public space? maybe

cities already have it.

Susi, T., Johannesson, M., and Backlund, P. (2007). Serious

games: An overview.

Tallman, C. (2020). personal communication.

Tomlinson, B., Nardi, B., Stokols, D., and Raturi, A. (2021).

Ecosystemas: Representing ecosystem impacts in de-

sign. In Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Confer-

ence, pages 1–10.

Tschimmel, K. and Santos, J. (2018). Design thinking ap-

plied to the redesign of business education. In ISPIM

Conference Proceedings, pages 1–11. The Interna-

tional Society for Professional Innovation Manage-

ment (ISPIM).

Tuite, K., Snavely, N., Hsiao, D.-y., Tabing, N., and

Popovic, Z. (2011). Photocity: training experts at

large-scale image acquisition through a competitive

game. In Proceedings of the 2011 CHI Conference,

pages 1383–1392.

Waern, A., Semeraro, A., Georgiev, N., Wang, R.,

Bergqvist, A., Back, J., Feng, S., Manjunath, K., and

Turmo Vidal, L. (2021). Moving embodied design ed-

ucation online. experiences from a course in embod-

ied interaction during the covid-19 pandemic. In Ex-

tended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference, pages

1–5.

Wang, L., Qian, J., and Ved, N. (2018). Urban memory:

Remembering communities in urban redevelopment.

In Extended Abstracts of the 2018 CHI Conference,

pages 1–6.

Wuthnow, R. (2019). The left behind: decline and rage in

small-town America. Princeton University Press.

SMARTGREENS 2023 - 12th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

26

Yasuda, K., Shiramatsu, S., Kawamura, I., Matsunaga, Y.,

Murakami, T., and Aoshima, H. (2021). Designing a

chatbot system for recommending college students to

counseling and collecting dialogue data. In Proceed-

ings of the 9th International Conference on Human-

Agent Interaction, pages 358–363.

The CommYOUnity Data Project: Exploring Novice Evaluations of Urban Spaces

27