Improving Learning Motivation for Out-of-Favour Subjects

Felix Böck

1a

, Dieter Landes

1b

and Yvonne Sedelmaier

1,2 c

1

Department of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, Coburg University of Applied Sciences and Arts,

96450 Coburg, Germany

2

Vocational Education, SRH Wilhelm Loehe University of Applied Sciences Fuerth, 90763 Fuerth, Germany

Keywords: Enriched Learning, Micro Learning, Gamification, Motivation Enhancement, non-Major Computer Science

Students, Out-of-Favour Subjects.

Abstract: Many curricula encompass subjects that are deemed less interesting or not important by a large share of

students since they cannot perceive their true significance. It is an open question how students can be

compelled to get involved with these subjects after all. This paper presents a novel concept how this can be

accomplished. In particular, the paper argues that four important requirements must be met, namely that

learning can also be accomplished in a less formal environment than regular lectures, learning may happen

independent of physical presence at the university and whenever students see themselves fit, learning is based

on small units, and students enjoy getting involved in the matter. As a proof-of-concept, this approach has

been used in programming education for students of electrical engineering, based on sending short summaries

via WhatsApp and adding playful elements. such as quizzes. An evaluation of the proof-of-concept over two

terms provides indication of the viability and usefulness of the approach, but also highlights several

opportunities for extensions and refinements.

1 INTRODUCTION

Occasionally, university curricula contain subjects

which are not at the centre of interest of a large share

of students. This may be due to the fact that students

view them only loosely, if at all, related to the core

subjects of their study program. For instance, many

students view non-major subjects such as, e.g.,

computer programming as foreign matter with limited

relevance in non-computer science majors such as

electrical engineering. Consequently, students

frequently lack motivation to get deeply involved in

the subject matter, resulting in poor performance.

Nevertheless, such out-of-favour subjects are

contained in the curriculum for a reason. Therefore,

students need to be coaxed into getting involved in

these subjects after all.

Thus, the research question is: “How can students

be successfully teased into getting involved in

subjects that they originally find dull?”. To answer

this research question, the paper presents a concept

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7382-8333

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0741-3540

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1022-1467

that may contribute to master this challenge. This

concept rests on four core elements which are

discussed in section 2, namely that learning can also

be accomplished in a less formal environment than

regular lectures, independent of physical presence at

the university and whenever students see themselves

fit, learning is based on small units, and students

enjoy getting involved in the matter.

As a proof-of-concept, the general concept is

instantiated in the context of computer programming

in an electrical engineering study program for

freshmen students. Section 3 presents details of this

approach which has been offered twice, each across a

complete term. The success of this approach is

evaluated quantitatively and qualitatively:

quantitatively by an analysis of usage behaviours,

qualitatively by a questionnaire-based survey,

accompanied by additional interviews. The details

and the results of the evaluation are included in

section 3, along with a comparison of related work.

The paper concludes with a discussion and an

outlook.

190

Böck, F., Landes, D. and Sedelmaier, Y.

Improving Learning Motivation for Out-of-Favour Subjects.

DOI: 10.5220/0011841400003470

In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2023) - Volume 1, pages 190-200

ISBN: 978-989-758-641-5; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

2 GENERAL CONCEPT

Making students work more intensively on subjects

that they do not like is a challenge. Students are

supposed to spend more time and effort on these

subjects, yet additional time is not feasible within the

curriculum without sacrificing other subjects.

Therefore, additional or intensified engagement

needs to take place beyond formal learning settings,

ideally embedded into normal student life. In addition,

there should be as few and simple roadblocks as

possible for getting started. This entails that

communication with the learners should use popular

channels which do not need to be newly established.

Furthermore, learning should not impose too much of

a burden on students, i.e. should happen almost

unnoticed. This implies small learning chunks that

can be accomplished without spending too much time.

Finally, students should be “rewarded” for getting

involved. Such a reward might be additional fun, e.g.

by elements with a game-like flavour.

We identified four key components of our concept

which link together in such a way that small tasks are

sent out to students over a communication channel

that they use anyway. The tasks are small enough to

be completed in a couple of minutes, wherever and

whenever students feel like it. If they master the task,

they obtain a virtual achievement.

2.1 Outside the Formal Context

Student learning does not take place only in

university, but rather in everyday life, e.g. through

exchanging information with friends or fellow

students, or searching for information. Historically,

educational institutions have been regarded as the

central place for learning, but non-formal learning

becomes increasingly popular, also with the facet of

lifelong learning (Reischmann, 1995, 2002). Thus, it

is important to create opportunities to enable learning

outside of firmly defined classroom settings.

2.2 Brain-Friendly Learning Elements

Several memory theories exist in psychology

(Atkinson and Shiffrin, 1968; Baddeley, 1998, 2002).

One of them, Cognitive Load Theory (Sweller, 1988),

states that learner’s working (or short-term) memory

has a limited capacity. Sweller explains three types of

cognitive load: intrinsic (how complex the task is),

extraneous (distractions that increase load), and

germane (linking new information with what is

already stored in long-term memory). The last aspect

is in line with newer learning theories such as

constructivism (Arnold and Siebert, 1999;

Braslavsky, 2001; Glasersfeld, 2001). An information

overload reduces the effectiveness of teaching.

Following Cognitive Load Theory, learning should

therefore happen in small learning units, so-called

micro learning elements.

2.3 Motivational Components

Self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan, 1985)

distinguishes different types of motivation. The most

familiar distinction is between “intrinsic motivation,

which refers to doing something because it is

inherently interesting or enjoyable, and extrinsic

motivation, which refers to doing something because

it leads to a separable outcome” (Ryan and Deci,

2000, p. 55). Lecturers of non-major subjects cannot

rely on intrinsic motivation to promote learning and

therefore need to know how to stimulate different

types of extrinsic motivation, e.g. by giving

incentives as a downstream reward for successful

implementation. Incentives are divided into

immaterial (e.g. approval or title) and material

incentives. These incentives should ideally boost

intrinsic motivation as well.

In order to transform passive media consumption

(Spitzer, 2012) into an active one, learning elements

should be enriched with incentives. The goal is to

introduce students to a learning offer that they use

voluntarily and intrinsically motivated. To foster

voluntary participation and active engagement, a

comprehensive incentive mechanism is proposed

which combines intrinsic and extrinsic motivators.

2.4 Digital Learning Environment

The most important criterion is the migration of the

learning content into the everyday life of students. For

this, the content needs to be included in a less formal

scope directly in the everyday routine without much

additional effort, using an appropriate medium.

Consequently, a suitable solution is subject to

several constraints: the learning environment must be

a digital one so that it can be used independently of

time and place. In addition, it already has to be an

existing component of the student’s daily life.

3 CASE STUDY

For the proof-of-concept, computer programming for

non-computer science majors (in our case: electrical

engineering) was chosen. In that context, the four

core elements of the concept need to be made more

Improving Learning Motivation for Out-of-Favour Subjects

191

concrete for students enrolled in these compulsory

courses. Frequently, non-major computer science

students are less motivated in the subjects than

students who only take the subjects voluntarily or

study computer science as a major.

Our surveys of the last terms indicate that many

students come directly from secondary school

(academic high school or higher secondary vocational

school) without previous practise. Also, our students

are non-major computer science students, which do

not have programming as their actual study goal, but

electrical or automation engineering, renewable

energies, and similar goals. This often means that

intrinsic motivation to learn programming is rather

limited. Yet, with digitalization software takes over

more and more central functions and programming

turns into a cross-sectional discipline, also for non-

majors.

In order to learn programming, it is important to

bring in continuity. Contact-hours devoted to learning

programming at universities are continuously

decreasing. To ensure continuity, learning

possibilities outside the classroom are required since

classes are already filled with theoretical issues. In

addition to continuity, practise is essential for being

able to apply the newly learned concepts.

Furthermore, motivation and time are correlated since

a lack of intrinsic motivation comes along with

devoting leisure time to other things than

programming. Thus, the question is: How to involve

students in programming outside the university in

order to increase motivation for the matter?

In our electrical engineering programs,

programming is a compulsory non-major subject in

the first terms with a workload of 8 out of 210 ECTS

points, split over two consecutive terms.

Programming has four contact hours per week which

encompass 2 hours lecture and 2 hours of lab

exercises. At the beginning There is quite a lot of time

between the classes, during which students tend to

forget part of the material that has not yet been

consolidated. Therefore, a short daily repetition on a

medium that is already widely used seems to be a

good start.

Most students are so-called “digital natives”

(Prensky, 2001), i.e. they have already grown up with

news services, messengers, and social media. This

implies that eLearning offers should be expanded

continuously by making use of novel technology and

digital tools. Spitzer also points to a shortened

attention span of young people (Spitzer, 2007, 2012),

which needs to be taken into account. Therefore,

learning materials need to be distributed over smaller

learning units. The incentive for students to focus on

a new, largely unknown (learning) offer can be

achieved through playful elements such as quizzes

(Hamari et al., 2014; Muntean, 2011). Young adults

typically are inclined to play which can be exploited

for motivating students to continue learning.

3.1 Research Design

The study was conducted twice in an iterative fashion,

i.e. some modifications due to findings in the first run

were already incorporated in the second iteration. In

particular, one year after the first run, the same project

was repeated with a new cohort of students based on

revised texts, occasionally accompanied by digital

media such as (animated) images or short videos. The

quiz component was also revised and the quiz

questions were expanded and doubled in total number,

allowing student to obtain more comprehensive

feedback.

The research design is composed of several

components. The objective usage data and their

analysis form the basis. On the subjective level, the

same questionnaire is used at the beginning and end

of the term (in two waves), where students were

requested to rate statements using a five-point Likert

scale. The questionnaires were supported by

qualitative interviews.

3.2 Methodical Approach

A messenger service was used to send out regular

summaries of the currently taught content, as a

repetition of what had been learned, outside the

lecture. The content to be learned was summarized

with varying degrees of detail and at varying lengths.

These summaries were initially sent on the day of the

lecture, then experimentally at different times of day

throughout the week in order to determine the

interaction rate. In addition to purely informative

messages, students should be stimulated to interact to

a larger extent and get involved with the material also

beyond formal classes. Therefore, questions and

quizzes were used to address the students’ natural

play instinct. A (knowledge/transfer) question about

the previously read content was asked. Students

answer the question voluntarily. Answers were

checked for validity by a bot and the result reflected

back to the students as a message. The result check is

based on deposited rules policy with affiliation to the

corresponding question. The quiz components

consisted of purely textual questions, small tasks and

multiple-choice questions with predefined answer

options. These short quiz tasks and summaries were

designed in such a way that they could be solved or

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

192

internalized in just a few minutes and are therefore a

good filler for time gaps. The format thus corresponds

to small, easily digestible learning snacks. The

procedure just described is based on the three theories

of enriched learning, micro learning (Hug et al., 2006),

and gamification (Deterding et al., 2011a), which are

described in the following sections. The last

subchapter shows the importance of an already used

communication channel to be able to include the

learning elements into the daily life of the students.

3.2.1 Enriched Learning

The term informal learning is not used uniformly in

literature, let alone that there is consensus of what

actually constitutes informal learning. Therefore, in

this paper, the approach used is called enriched

learning and defined subsequently.

Enriched learning builds upon formal learning,

i.e. within an organised structure. In this particular

case, formal learning is extended in terms of

flexibility (independent of place and time) and

manner of implementation, lower commitment, and

lower time and financial effort (Knowles, 1950). This

approach should make it possible for students to learn

in an organised framing, but in a less formal scope,

outside the university directly embedded in everyday

routines. In summary, enriched learning is defined as

targeted formal learning with a fixed and organized

curriculum, which, however, is characterized by

flexibility in terms of place and time, and low

commitment, and low time expenditure.

3.2.2 Micro Learning

To ensure that learning remains possible at any time

and regardless of location, the methodology of

microlearning (Hug et al., 2006) was applied and the

messages were sent in microcontent format. Micro

learning divides the learning context into so-called

micro content (Hug, 2005), i.e. many small learning

units which are absorbed more easily and processed

faster and easier by the brain. The content and the

understanding to be conveyed is usually checked at

the end of the small learning units by answering

questions, e.g. in the form of a quiz. Learners decide

where and when to learn. Time, content, curriculum,

form, process, learning preference, and mediality are

the dimensions of micro learning (Hug, 2005). They

can be adjusted individually to learning situations.

The idea of micro learning is in line with Cognitive

Load Theory (Miller, 1956; Sweller, 1988).

Nowadays short attention span of young people

(Spitzer, 2012) is a further reason for dividing the

content into smaller learning units, which ideally do

not exceed the attention span. This phenomenon is

also evident in teaching and research, where people

are increasingly turning to micro learning (Leong et

al., 2021).

3.2.3 Gamification

Gamification in learning settings aims at improving

students’ motivation and engagement. Additional

small gamification elements such as rankings or

badges for outstanding achievements can often

suffice as impulses to make tasks more interesting

(Hamari et al., 2014; Muntean, 2011). Deterding et al.

provided a definition and classification of the term

gamification which essentially characterizes

gamification as “the use of game design elements in

non-game contexts” (Deterding et al., 2011a, 2011b).

Traditionally, educational institutions usually

motivate their students already. For the correct

fulfilment of specifications and the associated

completion of tasks, students are usually awarded

points. Students are thus rewarded with more points

for desired behaviour and punished for undesired

behaviour. In this point system, badges are awarded

similar to grades whenever certain thresholds are

reached, such as “mastered the module very well”. If

the performance at the end of the term is sufficient,

the student can advance to the next higher term, or to

stay in the jargon of games: Advance to the next level.

Programming was promoted by gamification

elements like quizzes which create incentives. The

play instinct of students is addressed with

gamification to continue learning.

A pre-study (Figure 1) at the start of winter term

2019 shows that more than 2/3 of our students can be

motivated better with gamification elements (first bar

from left). The next question was aimed at the explicit

desire that playful elements are consistently present

in the lecture-accompanying eLearning course

(second bar from left) and that these are then also used

(third bar from left). At the end of the term, more than

90% of the participating students reported that they

had used the additional offers with gamification

elements in the lecture-accompanying eLearning

course.

3.2.4 WhatsApp

Based on observations in class and several interviews

with volunteers, possibilities to repeat course content

beyond university confines in their daily business

were identified. It turned out that most surveyed

students shared a habit of using social networks and

messenger services. These results are also consistent

with data we analysed in winter term 2018/2019.

Improving Learning Motivation for Out-of-Favour Subjects

193

Figure 1: Pre-study extract (winter term 2019/20).

These data indicate that almost 90% of all young

people and young adults surveyed actively use social

networks (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2022) and social

networks play a role in their private lives

(McDonald’s, 2017). The youngsters among the

approximately 42.8 million users of social networks

in Germany (Statista, 2019) spend an average of

around 214 minutes a day in social networks (mpfs,

2021). Closer examination and review of the

requirements revealed WhatsApp as a widespread

messenger service, which a large part of the students

already use on a daily basis.

Over 98% of teenagers actively use WhatsApp

every day (Faktenkontor, 2022). In another survey,

92% of the young people surveyed stated that they

used WhatsApp several times a day (elbdudler, 2018).

Thus, the most important decision was made for the

medium and at the same time the problem to install

an external application especially for the study was

overcome - WhatsApp is already installed on their

mobile devices anyway. A messenger service was

selected because it combines all the

requirements, such as time- and location-independent

learning, and can be included in everyday life through

the familiar environment - and is thus a perfect

complement to the classic classroom lecture. A

messenger service like WhatsApp, however, also

imposes some constraints with respect to the length

of the messages: messages need to be short enough,

but not too short to avoid losing essential aspects.

3.3 Current State of Research

WhatsApp is a messenger service developed to

communicate with family and friends which is used

to send text messages as well as short voice

recordings, pictures, or videos. In February 2020,

WhatsApp reached two billion monthly active users

(TechCrunch, 2020). Yet, by 2020, only one study

applied WhatsApp in higher education in Europe

(Venter, 2021): Existing studies do not integrate

WhatsApp in a didactic concept, even if a lecturer

uses WhatsApp in a course (Al-Omary et al., 2015) or

WhatsApp is used to give feedback to students

(Sugianto et al., 2021). WhatsApp is often used to

organize courses (Alabsi and Alghamdi, 2019) or for

improving communication between students and

lecturers (Najafi and Tridane, 2015) or with peers

(Albers et al., 2017; Jackson, 2019), for collaboration

within classrooms (Venter, 2021), but usually not as

a didactical element within a complex learning setting.

Quizzes in education follow a similar line. Some

studies exist, but either the research focusses on

technical aspects (e.g. Balog-Crisan et al., 2009;

ElYamany and Yousef, 2013; Gordillo et al., 2015),

or the research highlights quizzes as a single learning

element without embedding them in an overall

didactic concept (e.g.: Cavadas et al., 2017; Cicirello,

2009; Pollard, 2006). Only few studies contain an

overall didactical setting (Gamulin and Gamulin,

2012).

3.4 Observations, Experiences,

Evaluation and Results

The research shows that there is no published

approach to date that combines the four key

components described earlier. As described in the

research design, the study was conducted twice. For

this purpose, the uninterpreted observations were

written down, the collected data (usage data, survey

questionnaires and interviews) were evaluated and

finally analysed, interpreted, and discussed.

3.4.1 Observations and Experiences

After the introduction of the messenger service at the

beginning of winter term 2018/19, the number of

registrations increased rapidly to a total number of

n > 100. After an initial euphoria the demand and the

perceived interaction decreased until it stagnated with

a fixed number of users towards the fifth lecture

week. Often the questions that were sent with the

summary were overlooked and not answered,

especially if the question was in the middle of the

summary. Since this question often got lost in the

summary without getting the desired attention, the

question was sent as a separate message after a short

time, initially directly after the summary, later at

different times. Students often asked questions in

WhatsApp that were not covered by the bot’s rules for

technical reasons and were not compatible with the

instructor for time reasons.

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

194

These questions can roughly be categorized into

three categories. The first category was from the

beginning of the term until about the third week of the

term, when the questions were all about

organizational things like lecture times, lecture

rooms, and similar issues. Towards the end of the

term, the questions had a similar background and

focused almost exclusively on the upcoming final

examination and its formalities. The interesting

category for the lecturer was chronologically between

the third and the penultimate week of lectures, there

were isolated questions about the content of the last

lecture and a few questions about the lab exercises.

These could be the basis for deepening in the next

practice hours. During the weekly repetition at the

beginning of the lecture, many students also picked

up their mobile phones, probably to solve the question

asked by the lecturer with the help of the summary

from the messenger service.

In the second run in winter term 2019/2020, the

number of participants increased rapidly at the

beginning of the term and flattened out around the

third week of the term. Over the term, more than

100 active students used and interacted with the

service. The phenomenon from the first run with the

extracurricular questions to the chatbot at the

beginning and especially towards the end of the term

was observed again, despite several hints from the

lecturer to the students, although not to the full extent.

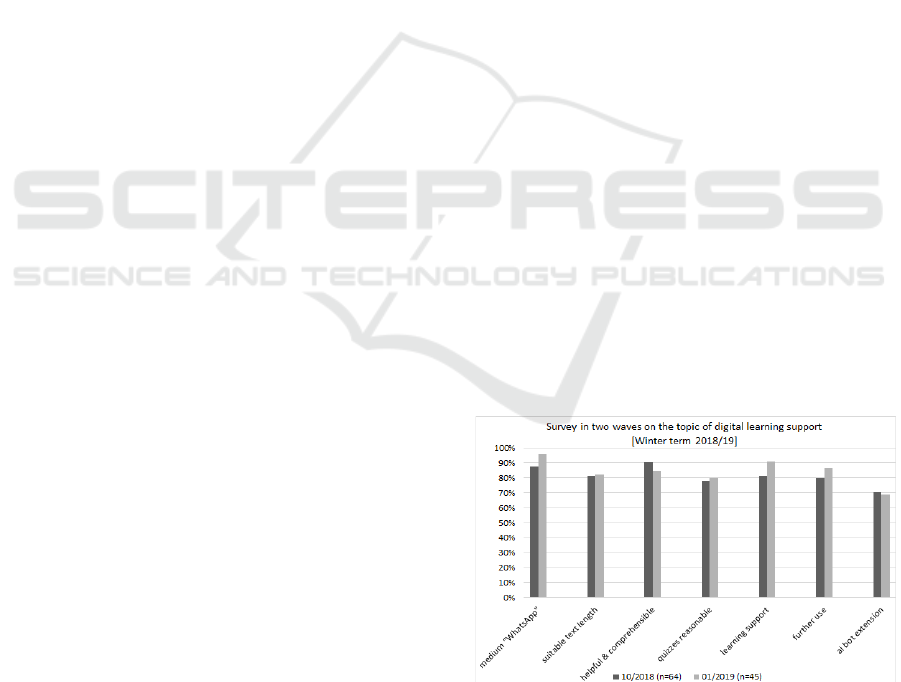

3.4.2 Evaluation

The basics of the evaluation from winter term

2018/19 are based on two waves of questionnaires

with all students present (Figure 2). The first wave

was carried out after the introductory session with

references to the topics to be covered and the

description of the messenger service. More than

90 students participated, but only 64 students

completed the questionnaire. The second wave was

distributed in the last lecture hour with a response of

approximately 70 copies including 45 complete ones.

Only complete responses were included in the

evaluation and the resulting outcomes. In addition to

the idea of sending summaries and quizzes via the

WhatsApp medium, the survey also asked whether

this feature was useful in the area of learning support

and repetition. In addition, it should be evaluated

which incentive is decisive for the use of this offer.

The desired length at the beginning of the term was

also asked at the end with the actual length of the

summaries. In addition to the motivation to use this

service, the current usage statistics were also

compared. Volunteers (n = 5) were invited to a

personal interview after completing the examination

at the end of the term and this was subsequently

evaluated. The number of active users over the whole

term was always above 85 students.

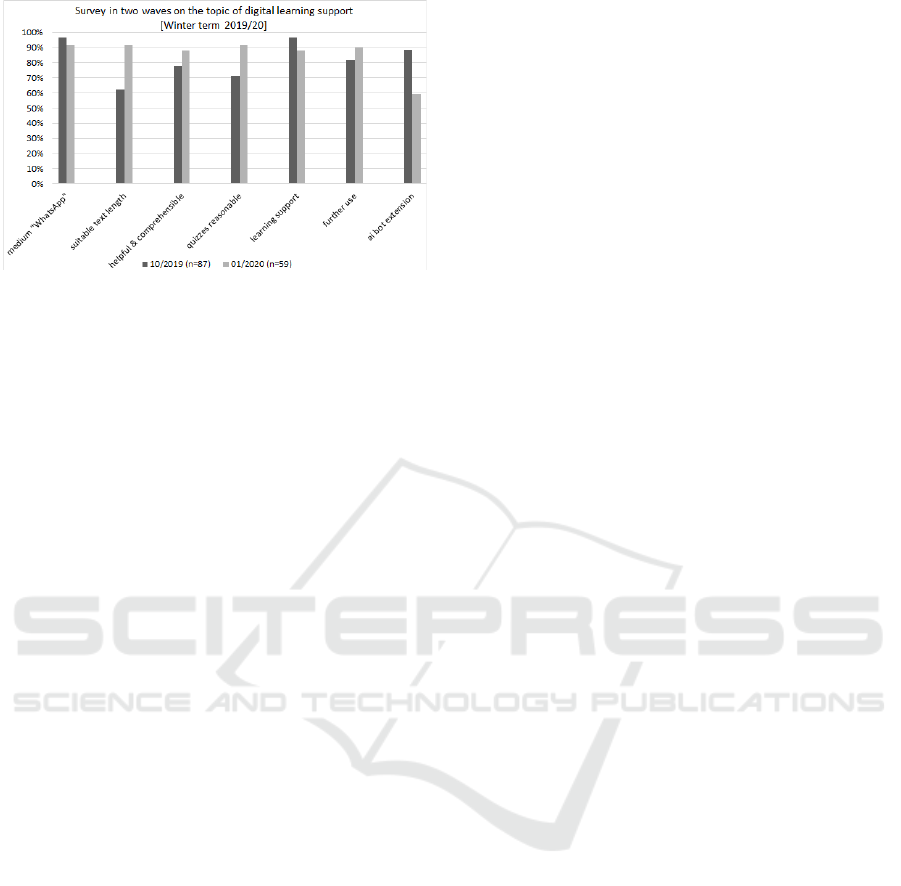

Also, in the winter term one year later, the same

questionnaire was distributed in two waves at the

beginning and at the end of the term. The first wave

of the questionnaire was administered during the third

week of classes and was designed to capture initial

impressions and assumptions. More than

120 students participated, 87 students fully

completed the questionnaire. The second wave was

distributed during the penultimate hour of lectures

and had a response of approximately 90 copies

including 59 complete ones. Only fully complete

responses were included in the analysis and resulting

findings. Figure 3 shows a relevant excerpt of the

evaluation of the survey questionnaires for the winter

term 2019/20. The questionnaires were supported and

evaluated by means of voluntary, qualitative

interviews at the beginning (n = 10) and at the end of

the term (n = 7). The number of active users was

always above 105 students throughout the term.

In both diagrams (Figure 2 and Figure 3), the

darker bars reflect the expectations at the beginning

of the respective term (1

st

survey wave) and the

lighter bar at the end of the term then reflects the self-

reflective feedback (2

nd

survey wave). The first

question tried to find out whether WhatsApp is

suitable for the project of sending short summaries

and quizzes to students. The second question was

related to the specific length of the individual

messages and summaries: Is the targeted average

length of the messages appropriate or not? After the

question of format, the third question assessed the

content of the summaries, i.e. has the content of the

summary been very helpful and understandable from

the student’s point of view? Following this, the fourth

question is to provide legitimacy to the quiz questions

at the end of each summary. The fifth question is for

self-reflection on whether, from the student’s point of

view, the WhatsApp service is or was a meaningful

and useful feature in learning support and revision.

From this, the sixth question can be derived, whether

students would like to continue using the WhatsApp

service in the future. The last (seventh) question is a

hypothetical one. Extension of the rule-based bot with

an “artificial intelligence” so that all questions from

the student side that are not directly mapped can also

be answered automatically. Both the free-text

questions in the surveys and the follow-up interviews

were used to validate previous results. For example,

the seventh question was justified by the fact that a

possible feeling of shame can be very profound

Improving Learning Motivation for Out-of-Favour Subjects

195

among first-term students and therefore they often do

not dare to ask the lecturer. A digital learning

assistant could provide a remedy here. All seven

questions highlight the high readiness of use and its

conviction from the student’s perspective. The

relative statement across the two different cohorts

also shows a similarly high significance.

3.4.3 Results and Discussion

The reactions of the students in both trials after the

announcement and introduction of the service were

very positive in the first attempt (before their self-

test) and had an encouragement of almost 100%

without any headwind. Also, the resume at both ends

of the terms were uniformly positive with a few

suggestions for expansion. Even after evaluations of

the interviews and surveys, students issued no

negative opinions of the about the offer. Students’

opinions on the difficulty and number of quiz

questions varied greatly from “exactly right” to “too

few and too simple, please more to puzzle over”.

Messages sent at different times in a familiar

medium were actively used by over 50% of the

students in the course (n = 85 respectively n = 105).

Active use refers to regular interaction (mostly

answers) with questions from students over the course

of an entire term. In surveys and interviews across

both terms, the participants stated that 70% consider

the possibility to offer a very useful service and more

than 80% consider the service as useful for learning

support and repetition. During the term, it became

apparent that the time and length of the sent messages

plays a vital role with respect to response rates. The

longer the message was or the later it was sent, the

less interaction there was. Occasionally there were

answers on the following day (approximately 20% of

all answers). The highest interaction is from Monday

to Friday between 7 pm and 10 pm with an active

participation of nearly 77%. The time slots 6 pm till

8 pm on the weekend (Saturday/Sunday and holidays)

achieve a similarly high quota. The length per

message should not exceed 1.600 characters, as

WhatsApp will then hide this with the note: read more

(status submission of the paper). This additional click

on ‘read more’ and scrolling length makes users shy

away from reading the text. Over the term and after

evaluation of surveys and interviews, it is apparent

that the summaries must be sent out promptly after

the lecture, in order to receive the necessary attention.

Furthermore, questions must be sent individually and

not together with the summary, otherwise they are

easily overlooked. Students highly appreciate proper

formatting and structure of the message, e.g. bold

headlines, enough read-friendly paragraphs, or source

code in italics. The use of emojis to make the text

more structured and to enable faster entry points

when reading was also considered useful throughout.

Several times the combination of learning content and

modern techniques was praised as well as the

automatic memory in a trusted environment, so that

the learning material is not forgotten from one class

to the next. A change of the mobile device can be seen

as a critical point because previous messages are lost.

In case of a loss or change of mobile phone, it is

desirable to obtain all previous summaries and

questions again on a new device, so that a learning

gap can be avoided.

In conclusion, the second round of the project also

showed that students would like to see the expansion

of such digital learning assistants and also directly

substantiate this with ideas. The most common

request was an adaptation of the learning content.

Thus, most students wished for adaptive summaries

on a continuum between “short and concise

overview” to “somewhat more sophisticated and

detailed summaries”. The same also applies to the

quizzes, which, according to multiple statements

from students, would have liked to have “tough

brainteasers which require specialist knowledge”.

These points can be incorporated very well as

requirements for future implementations.

Students reported that they used the summaries

and questions as “perfect exam preparation”

(Pseudonymised student). The success in the written

exam cannot be justified exclusively by the usage of

the messaging service, but the statistics show that

basics and theory can be conveyed very well via a

messenger service and that students have achieved

better results on average with the use of the method.

Figure 2: Survey extract (winter term 2018/19).

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

196

Figure 3: Survey extract (winter term 2019/20).

The added value for students was large (according

to the student statements), at least for basic chapter

and theory, while the (time) effort was very low.

However, the students also stated that they did not

consider this offer useful for all subjects.

For the research question posed at the beginning,

this means that this approach constitutes a possible

way to improve learning motivation for out-of-favour

subjects to less motivated students in an entertaining

way outside of lecture and to increase their interest in

the long run. Yet, the approach has not yet exploited

its full potential, and the students’ wishes should be

incorporated in the further planned cycles for a

comprehensive and widely accepted offer of digital

learning assistance.

4 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

The aim of this project was to increase the interest and

thus also the motivation of students in subjects that

are rather unpopular. To this end, a concept was

presented and developed based on four core elements,

namely that learning is also possible in a less formal

environment than in regular lectures, independent of

physical presence at the university and whenever

students see fit, that learning is based on small units

and that students enjoy engaging with the material. In

the concrete implementation of the proof-of-concept

of this concept, this meant short learning units in

microlearning style outside the university (enriched

learning) in familiar surroundings and already used

medium (WhatsApp) with gamification elements,

such as quizzes, as motivation drivers. The micro

learning approach was chosen as the basis in order to

divide the learning material into small brain-friendly

parts, which can be quickly understood. In addition,

students need to take very little time to read

summaries or answer short quiz questions, so that the

small learning unit can be “hidden” in everyday life.

The added value on the student side is clearly visible

after only a few messages. For instructors, effort is

limited after initial creation of the material, i.e.

summaries, quizzes etc. The latter incurs considerable

effort, but the material can simply be reused in future

issues of the course. The initial creation of the

summaries and questions in the quiz pool takes time,

but they can all be reused in the following terms

without problems. These short summaries and the

questions from the quiz pool were sent via a widely

distributed message service (WhatsApp), which is

installed on the majority of students’ smartphones and

creates a familiar environment.

This approach can be recommended for the same

target group, since both the acceptance among the

students is very high, as well as the improvement of

the activation to deal (intentionally) with the content

of computer science is increasing. As well-

intentioned advice from the students’ side, it should

be mentioned that the offer should be offered on a

purely voluntary basis and that important information

should also be disseminated over other channels.

The Novelty Effect, which describes a bias for

newer technologies (Clark and Sugrue, 1988), cannot

be completely disregarded. Although the proof-of-

concept involved repeating the project with different

cohorts, individually it was something completely

new in their studies. Therefore, it remains to be seen

whether the demonstrated effect is reduced due to the

novelty effect, or remains constant. Therefore, it must

also be examined whether long-term repeatability and

transferability to other courses is possible. We were

able to show that with the help of WhatsApp and a

suitable didactic concept - in which individual

assessment units are not planned too large and the

completion time is a maximum of 2 to 3 minutes -

students could be more motivated for less enthusiastic

subjects with gamification elements. This is proven

by the evaluation of the objective usage data as well

as the evaluation of the survey questionnaires and

qualitative interviews.

Future work might address expanding textual

summaries permanently by short learning videos or

audio recordings on a regular basis. Voice memos are

becoming more popular and sent more often than text,

according to feedback from our students. However, a

possible down-side could be that voice messages

cannot always be listened to immediately in direct

comparison to text and could therefore remain

unanswered for a longer period of time. Other

frequently mentioned requests from students are the

use of the channel for organizational topics, such as

Improving Learning Motivation for Out-of-Favour Subjects

197

room changes and appointments, more concrete

examples on the topics and summaries and a few

difficult puzzle tasks to clear up. Also, students

(approximately 55% of all students) would care for

answers to individual questions through this channel,

but this will probably take a lot of time as long as this

cannot be covered by an automated bot with

“artificial intelligence”. During the evaluation of the

communication between the students and the lecturer,

the appeal and the personalization were very often

noticed. Basically, the content should be in the

foreground of the methodology, but the unidirectional

communication can be extended to a more

bidirectional communication by personifying the

messenger service. As soon as the bot with “artificial

intelligence” receives a name and also a profile

picture, the impersonal message of a system would

become the personal learning consultation, which one

would rather ask for advice than a thing. Ideally, the

bot as a digital learning companion would select the

same answers or better ones as a lecturer, so that,

according to the Turing Test (Russell and Norvig,

2016), no difference is discernible for the learner.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is partly funded by the German Ministry of

Education and Research (Bundesministerium für

Bildung und Forschung) under grants 01PL17022A

and 16DHBKI090.

REFERENCES

Alabsi, K. M. and Alghamdi, F. M. A. (2019). Students’

Opinions on the Functions and Usefulness of

Communication on WhatsApp in the EFL Higher

Education Context. In Arab World English Journal,

1(1), pp. 129–143. AWEJ.

Albers, R. et al. (2017). Inquiry-based learning: Emirati

university students choose WhatsApp for collaboration.

In Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: Gulf

Perspectives, 14(2), pp. 37–53. Emerald.

Al-Omary, A. et al. (2015). The Impact of SNS in Higher

Education: A Case Study of Using WhatsApp in the

University of Bahrain. In 5th International Conference

on e-Learning "Best Practices in Management, Design

and Development of e-Courses: Standards of

Excellence and Creativity" (ECONF), pp. 296–300.

IEEE.

Arnold, R. and Siebert, H. (1999). Konstruktivistische

Erwachsenenbildung: Von der Deutung zur

Konstruktion von Wirklichkeit (3rd ed.). Schneider

Verlag Hohengehren.

Atkinson, R. C. and Shiffrin, R. M. (1968). Human

Memory: A Proposed System and its Control Processes.

In K. W. Spence & J. T. Spence (Eds.). Psychology of

Learning and Motivation. The psychology of learning

and motivation: Advances in research and theory (Vol.

2, pp. 89–195). Academic Press.

Baddeley, A. (1998). Recent developments in working

memory. In Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 8(2), pp.

234–238. ScienceDirect.

Baddeley, A. (2002). Is Working Memory Still Working?

In European Psychologist, 7(2), pp. 85–97. hogrefe.

Balog-Crisan, R. et al. (2009). Ontologies for a Semantic

Quiz Architecture. In 9th International Conference on

Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), pp. 492–

494. IEEE.

Braslavsky, C. (Ed.) (2001). Prospects: quarterly review of

comparative education: XXXI, 2. Constructivism and

education: No 118. UNESCO International Bureau of

Education.

Cavadas, C. et al. (2017). Quizzes as an active learning

strategy: A study with students of pharmaceutical

sciences. In 12th Iberian Conference on Information

Systems and Technologies (CISTI), pp. 1–6. IEEE.

Cicirello, V. A. (2009). On the Role and Effectiveness of

Pop Quizzes in CS1. In 40th ACM technical symposium

on Computer science education (SIGCSE), pp. 286–

290. ACM.

Clark, R. E. and Sugrue, B. M. (1988). Research on

Instructional Media, 1978-1988. In D. P. Ely (Ed.).

Educational media and technological yearbook

(pp. 327–343). Libraries Unlimited.

Deci, E. L. and Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation

and self-determination in human behavior.

Perspectives in social psychology. Plenum Press.

Deterding, S. et al. (2011a). From game design elements to

gamefulness: Defining "Gamification". In 15th

International Academic MindTrek Conference

Envisioning Future Media Environments (MindTrek),

pp. 9–15. ACM.

Deterding, S. et al. (2011b). Gamification: Toward a

Definition. In Extended abstracts on Human factors in

computing systems (CHI EA), pp. 12–15. ACM.

ElYamany, H. F. and Yousef, A. H. (2013). A Mobile-Quiz

Application in Egypt. In 4th International Conference

on e-Learning "Best Practices in Management, Design

and Development of e-Courses: Standards of

Excellence and Creativity" (ECONF), pp. 325–329.

IEEE.

Gamulin, J. and Gamulin, O. (2012). The application of

web-based formative quizzes in laboratory teaching in

higher education environment. In 35th International

Convention MIPRO, pp. 1383–1388. IEEE.

Glasersfeld, E. von (2001). Radical constructivism and

teaching. In C. Braslavsky (Ed.). Prospects: quarterly

review of comparative education: XXXI, 2.

Constructivism and education: No 118 (pp. 161–174).

UNESCO International Bureau of Education.

Gordillo, A. et al. (2015). Enhancing Web-Based Learning

Resources with Existing and Custom Quizzes Through

an Authoring Tool. In IEEE Revista Iberoamericana

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

198

De Tecnologias Del Aprendizaje, 10(4), pp. 215–222.

IEEE.

Hamari, J. et al. (2014). Does Gamification Work? — A

Literature Review of Empirical Studies on

Gamification. In 47th Hawaii International Conference

on System Sciences (HICSS), pp. 3025–3034. IEEE.

Hug, T. (2005). Micro Learning and Narration: Exploring

possibilities of utilization of narrations and storytelling

for the designing of “micro units” and didactical micro-

learning arrangements. In 4th Media in Transition

conference (MiT). MIT.

Hug, T. et al. (2006). Microlearning: Emerging Concepts,

Practices and Technologies after e-Learning. Uiversity

Press.

Jackson, E. A. (2019). Use of Whatsapp for flexible

learning: Its effectiveness in supporting teaching and

learning in Sierra Leone’s Higher Education

Institutions. MPRA.

Knowles, M. S. (1950). Informal adult education. A guide

for administrators, leaders, and teachers. Association

Press.

Leong, K. et al. (2021). A review of the trend of

microlearning. In Journal of Work-Applied

Management, 13(1), pp. 88–102. Emerald.

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or

minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing

information. In Psychological Review, 63(2), pp. 81–97.

American Psychological Association.

Muntean, C. I. (2011). Raising engagement in e-learning

through gamification. In 6th International Conference

on Virtual learning (ICVL), pp. 323–329. National

Institute for Research & Development in Informatics –

ICI Bucharest.

Najafi, H. and Tridane, A. (2015). Improving Instructor-

Student Communication Using Whatsapp: A Pilot

Study. In 8th International Conference on

Developments of E-Systems Engineering (DeSE),

pp. 171–175. IEEE.

Pollard, J. K. (2006). Student reflection using a Web-based

Quiz. In 7th International Conference on Information

Technology Based Higher Education and Training

(ITHET), pp. 871–874. IEEE.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. In

on the Horizon, 9(5), pp. 1–6. MCB University Press.

Pseudonymised student. Interview by Felix Böck.

Reischmann, J. (1995). Die Kehrseite der

Professionalisierung in der Erwachsenenbildung:

Lernen “en passant” - die vergessene Dimension. In

Grundlagen Der Weiterbildung: GdWZ; Praxis,

Forschung, Trends; Zeitschrift Für Weiterbildung Und

Bildungspolitik Im in- Und Ausland, 6(4), pp. 200–204.

Neuwied.

Reischmann, J. (2002). Lernen hoch zehn – wer bietet

mehr? Von „Lernen en passant” zu „kompositionellem

Lernen” und „lebensbreiter Bildung”. In Vielfalt Neu

Verbinden – Abschlussbericht Zum Projekt „Lernen

2000plus – Initiative Für Eine Neue Lernkultur" (Kath.

Bundesarb.Gem. F. Erw.Bildung), pp. 159–167. Bitter.

Russell, S. and Norvig, P. (2016). Artificial intelligence: A

modern approach. Pearson, 3rd edition.

Ryan, R. M. and Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and Extrinsic

Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions.

In Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), pp.

54–67. ScienceDirect.

Spitzer, M. (2007). Lernen: Gehirnforschung und die

Schule des Lebens (3rd ed.). Spektrum Akademischer

Verlag Elsevier.

Spitzer, M. (2012). Digitale Demenz: Wie wir uns und

unsere Kinder um den Verstand bringen. Droemer TB.

McDonald’s (05.09.2017). Welche Rolle spielen soziale

Netzwerke wie z. B. Instagram oder Facebook in Ihrem

Leben, für Sie privat? Site was accessed 01.11.2022,

Retrieved from https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/

studie/754400/umfrage/umfrage-zum-stellenwert-

sozialer-netzwerke-im-privaten-bereich/.

Elbdudler (06.03.2018). Anteil der Befragten der

Generation Z, die folgende Social-Media-Apps

mehrfach täglich nutzen, in Deutschland im Jahr 2017.

In Statista. Site was accessed 01.11.2022, Retrieved

from https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/

815477/umfrage/mehrfach-taegliche-nutzung-von-

social-media-apps-in-der-generation-z-in-deutschland/.

Statista (18.02.2019). Anzahl der Nutzer von sozialen

Netzwerken in Deutschland in den Jahren 2017 und

2018 sowie eine Prognose bis 2023 (in Millionen). In

Statista. Site was accessed 01.11.2022, Retrieved from

https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/554909/

umfrage/anzahl-der-nutzer-sozialer-netzwerke-in-

deutschland/.

TechCrunch (12.02.2020). Anzahl der monatlich aktiven

Nutzer von WhatsApp weltweit in ausgewählten

Monaten von April 2013 bis Februar 2020 (in

Millionen). In Statista. Site was accessed 01.11.2022,

Retrieved from https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/

studie/285230/umfrage/aktive-nutzer-von-whatsapp-

weltweit/.

Mpfs (30.11.2021). Tägliche Dauer der Internetnutzung

durch Jugendliche in Deutschland in den Jahren 2006

bis 2021 (in Minuten). In Statista. Site was accessed

01.11.2022, Retrieved from https://de.statista.com/

statistik/daten/studie/168069/umfrage/taegliche-

internetnutzung-durch-jugendliche/.

Faktenkontor (14.06.2022). Anteil der befragten

Internetnutzer, die WhatsApp nutzen, nach

Altersgruppen in Deutschland im Jahr 2021/22. In

Statista. Site was accessed 01.11.2022, Retrieved from

https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/691572/

umfrage/anteil-der-nutzer-von-whatsapp-nach-alter-in-

deutschland/.

Statistisches Bundesamt (04.04.2022). Anteil der

Internetnutzer, die in den letzten drei Monaten soziale

Netzwerke genutzt haben, nach Altersgruppen in

Deutschland im Jahr 2021. In Statista. Site was

accessed 01.11.2022, Retrieved from https://

de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/509345/umfrage/

anteil-der-nutzer-von-sozialen-netzwerken-nach-

altersgruppen-in-deutschland/.

Sugianto, A. et al. (2021). Feedback in a Mediated

WhatsApp Online Learning: A Case of Indonesian EFL

Postgraduate Students. In 3rd International Conference

Improving Learning Motivation for Out-of-Favour Subjects

199

on Informatics, Multimedia, Cyber and Information

System (ICIMCIS), pp. 220–225. IEEE.

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive Load During Problem

Solving: Effects on Learning. In Cognitive Science,

12(2), pp. 257–285. Wiley.

Venter, M. (2021). A model of using WhatsApp for

Collaborative Learning in a Programming Subject. In

19th International Conference on Information

Technology Based Higher Education and Training

(ITHET), pp. 1–8. IEEE.

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

200