Engagement, Participation, and Liveness: Understanding Audience

Interaction in Technology-Based Events

Genildo Gomes

a

, Tayana Conte

b

, Tha

´

ıs Castro

c

and Bruno Gadelha

d

Institute of Computing, Federal University of Amazonas, Manaus, AM, Brazil

Keywords:

Engagement, Audience Participation, Liveness, Events.

Abstract:

Technologies have been changing how the audience participates in different events. This participation is dis-

tinct in each type of event. For example, in educational settings, polls with clickers and word clouds are

usually used to involve the audience. For music festivals and other musical performances, organizers opt out

of providing led sticks, necklaces and wristbands. Different uses for the smartphones, such as using them as

lanterns aiming at obtaining crowd effect, are other ordinary and spontaneous ways of interaction. Recently,

more research has been published in journals and scientific conferences discussing the use of these technolo-

gies, with techniques for fostering interaction and collaboration. Therefore, we conducted a literature review

using forward and backward snowballing, looking for articles about how researchers use new technologies

to increase audience experience in different contexts of events and what concepts are raised from that per-

spective. As a result, we propose a taxonomy of those concepts related to audience experience through three

lenses: engagement, participation, and liveness.

1 INTRODUCTION

Events are spacial-temporal phenomena with unique

characteristics, differing from environment interac-

tion and audiences (Getz, 2008). In this sense,

there are many types of events ranging from rituals,

and conference presentations, to music performances

(Johnny Allen, 2010; Getz and Page, 2016).

In several types of events, especially entertain-

ment events, the massive use of technologies to en-

gage the audience creates opportunities for interaction

with the event. Performers and event managers seek

technological alternatives to improve interaction and

audience engagement. It is necessary to provide the

audience different experiences for different contexts

and for different spaces, such as virtual, physical (face

to face), and hybrid(Webb et al., 2016).

In this sense, audience participation has been ex-

plored in different ways providing technological in-

teraction. For instance, in competitive and collabora-

tive settings (Martins et al., 2020; de Freitas Martins

et al., 2020; Martins et al., 2021), music creation (Wu

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2901-3994

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6436-3773

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6076-7674

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7007-5209

et al., 2017; H

¨

odl et al., 2020), or visual effects in the

crowd (Gomes et al., 2020; Vasconcelos et al., 2018).

In virtual spaces, the audience can interact with the

streamer using poll sections during live streamings

(Striner et al., 2021). Besides, remote audience in-

teraction can be mediated by interactive platform re-

sources, for example, reactions such as likes (Li et al.,

2019; Tang et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2017; Br

¨

undl

and Hess, 2016), text comments (Lu et al., 2021; Tang

et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2020; Li et al., 2019) and

stickers (Lu et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2019). All these

previous works explore different aspects that impact

technological event interaction. Such aspects include

audience distribution (Webb et al., 2016), engagement

facets (Latulipe et al., 2011), or competitive, collabo-

rative and cooperative aspects (Martins et al., 2021).

Investigating how interactive technological expe-

riences occur in events makes it possible to under-

stand how to design technologies to support new ex-

periences. Likewise, it is relevant to consider differ-

ent contexts of events, whether face-to-face, virtual or

hybrid (Webb et al., 2016); the event type being ex-

perienced or the audience attending the performance.

Therefore, this interaction can promote engagement

and audience participation during the event.

Previous studies already presented different en-

gagement and participation aspects, such as Wu et al.

264

Gomes, G., Conte, T., Castro, T. and Gadelha, B.

Engagement, Participation, and Liveness: Understanding Audience Interaction in Technology-Based Events.

DOI: 10.5220/0011848600003467

In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2023) - Volume 2, pages 264-275

ISBN: 978-989-758-648-4; ISSN: 2184-4992

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

(2017) by establishing a framework to classify par-

ticipatory live music systems. Striner et al. (2021)

present a thematic map considering audience partic-

ipation from live streaming. Apart from those work,

there is a need for more research regarding a greater

variety of events and interaction forms, starting with

the perspective of how interactive technology affects

the audience experience. Therefore, based on this

context, we aim to answer the following question:

How do research in HCI and CSCW areas approach

technological interaction in events?

To answer that question, we conducted an ex-

ploratory literature review using a snowballing tech-

nique to map concepts regarding technology inter-

action in events. Those concepts were organized

through three primary lenses: Engagement, Partici-

pation, and Liveness.

From the three lenses perspective, we aimed to ob-

tain a general vision of how interactive technology is

present in different events. By identifying the con-

cepts associated with the lenses, this paper provides a

taxonomy to understand the factors affected by the ex-

perience related to interaction technologies in events.

2 BACKGROUND

To better understand events with technological inter-

action, we need a theoretical basis regarding types of

events and audience. Events are planned to specific

special occasions, reach objectives and social meters,

cultural and corporative (Johnny Allen, 2010). Events

are commonly explored by tourism as an entertain-

ment alternative and promote the local economy. In

this sense, we used the Getz (2007) proposed typol-

ogy involving eight types of events, being: recre-

ative Events, political and state events, cultural cele-

brations, arts and entertainment events, sporting and

competitive events, commercial events, educational

and scientific events, and private events.

Just as events have distinct characteristics, audi-

ences have goals that drive them to participate. There-

fore, audiences are groups of people who participate

in the event. An audience can be recognized accord-

ing to size, purpose, and interest level (Mackellar,

2013). Exploring audience behaviors concerning the

event helps to identify characteristics of the techno-

logical interaction (Martins et al., 2021). Mackellar

(2013) builds on audience goals to categorize them

into five different types: mass audience, special inter-

est audience, community event audiences, incidental

audiences, and media audiences.

2.1 Related Works

Previous works address several methods to promote

audience participation mediated by technologies, ex-

ploring characteristics such as interactivity and im-

mersion in distributed performances (face-to-face, re-

mote and hybrid)(Webb et al., 2016; Martins et al.,

2021). From this perspective of technological interac-

tion, researchers observe factors that affect audience

behavior in different contexts, whether expressiveness

(e.g.: actively or passively) (Cerratto-Pargman et al.,

2014; H

¨

odl et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2020; Gomes

et al., 2020), the degree of participation (Cerratto-

Pargman et al., 2014) or audience expectations from

technological interaction (Li et al., 2019).

Wu et al. (2017) present a framework for clas-

sifying participatory live music performances. The

framework is inspired by participatory art forms and

based on audience participation levels. The frame-

work was used to classify a tool’s characteristics to

promote audience participation, the Open Symphony.

Features such as modalities, media, and motivation

affordances were identified in the tool.

Cerratto-Pargman et al. (2014) seek to understand

audience participation in interactive theater perfor-

mances. Audience members were encouraged to in-

teract and contribute to the performance by answering

questions related to the plot of the theatrical scene. To

understand the audience participation experience, the

authors designed a framework to identify the quali-

ties that emerged during the performance. Three main

qualities were identified: Constitutive, Epistemic, and

Critical. As a result, the authors identified different

individual and collective audience behaviors and re-

actions.

The works described above concepts related to

specific contexts of technological interaction: musical

interaction in concerts and live-streaming of games

and plays. Although they have been described in

specific contexts, we can observe their application to

other events. In this paper, we sought to organize

such concepts considering events of different pur-

poses where some technological interaction occurs.

Thus, we present a taxonomy that organizes such con-

cepts and guides researchers and technology devel-

opers to foster the audience experience at different

events.

Engagement, Participation, and Liveness: Understanding Audience Interaction in Technology-Based Events

265

3 A TAXONOMY OF CONCEPTS

RELATED TO

TECHNOLOGICAL

INTERACTION IN EVENTS

This research investigates the factors affected by the

user experience associated with interaction technol-

ogy at events. We propose a taxonomy of concepts

related to technological interaction at events based on

an exploratory literature review using backward and

forward snowballing techniques (Kitchenham et al.,

2015). By definition, a Taxonomy is ”a controlled vo-

cabulary with each term having hierarchical (broader

and narrower) and equivalent (synonymous) relation-

ships” (Whittaker and Breininger, 2008). The tax-

onomy supports the identification and understanding

of the concepts that characterize the technological in-

teraction in various events. Besides this, it can help

designers and researchers as a basis to conceptualize

how technology can affect audience behavior.

To create a taxonomy, we followed a sequence

of five steps: 1

st

, exploratory literature review; 2

nd

,

snowballing; 3

rd

exploratory search in national and

Latin American events, 4

th

concepts extraction; 5

th

,

concept synthesis.

In the 1

st

step, we carried out an exploratory lit-

erature review starting with a manual review of the

proceedings of the main event in the area of Collabo-

rative Systems (CSCW), considering the last six years

(2016-2021). Due to the audience’s spontaneous col-

laborative actions in events being a joint initiative, we

used the main proceeding of the area (CSCW) as a

starting point.

As inclusion criteria, we selected papers that ex-

plore concepts related to audience interaction, experi-

ence, and participation through artifacts and techno-

logical resources at events. In total, 1382 papers were

analyzed by reading the title and abstract. From the

reading of the title and abstract, we selected 21 pa-

pers to read fully. The inclusion criterion was applied

again, and as a result, five papers were selected. From

these works, we carried out a backward and forward

snowballing (2

nd

step) to complement the research on

definitions and concepts related to technological in-

teraction in events.

Backwards snowballing is when we use the

reference list to identify new papers to include in the

review. Forward snowballing is a locating process of

all papers citing a known article (Kitchenham et al.,

2015). For the forward snowballing we used Google

Scholar

1

virtual library.

Snowballing technique made it possible to ana-

lyze 63 new papers, 40 returned from backward snow-

balling and 23 from forward snowballing. The papers

returned are from important vehicles, such as Confer-

ence on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI),

Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction

(NordiCHI), Symposium on Computer-Human Inter-

action in Play (CHI PLAY) and Conference on Expe-

riences for TV and Online Video (TVX).

In a complementary way, we conducted an ex-

ploratory search in the main proceedings of the

Brazilian and Latin American events of HCI and Col-

laborative Systems to dialogue with previous works

already published (3

rd

step) where 5 papers were se-

lected. The selected papers are listed in a report avail-

able as supplementary material

2

.

From the set of papers obtained from this process,

we conducted the identification and organization of

concepts related to the interaction and experience of

the audience at events (4

th

step). In 5

th

step, four re-

searchers followed the selection, analysis of these pa-

pers, concept extraction, and taxonomy consolidation.

The process of consolidation occurred through meet-

ings with the authors of this paper. In these meetings,

we discussed how the concepts obtained affected the

audience’s experience, how we can explore them in

the future in other contexts, and how technology evi-

dence/affects/provides such a concept.

During the analysis, we noted several concepts re-

lated to engagement, participation, and liveness. Con-

cepts associated with audience excitement and emo-

tions were grouped in the engagement lens; the con-

cepts that describe audience behaviors were grouped

in the participation lens; the concepts that describe the

experience of living a real-time event were grouped in

the liveness lens. We defined these lenses in the con-

cept synthesis step, using them as perspectives to or-

ganize the identified concepts in a taxonomy. In this

sense, specific papers were analyzed to characterize

these lenses better conceptually. Not all of these spe-

cific papers are about the context of events with tech-

nological interaction, but they were necessary for the-

oretical deepening

3

.

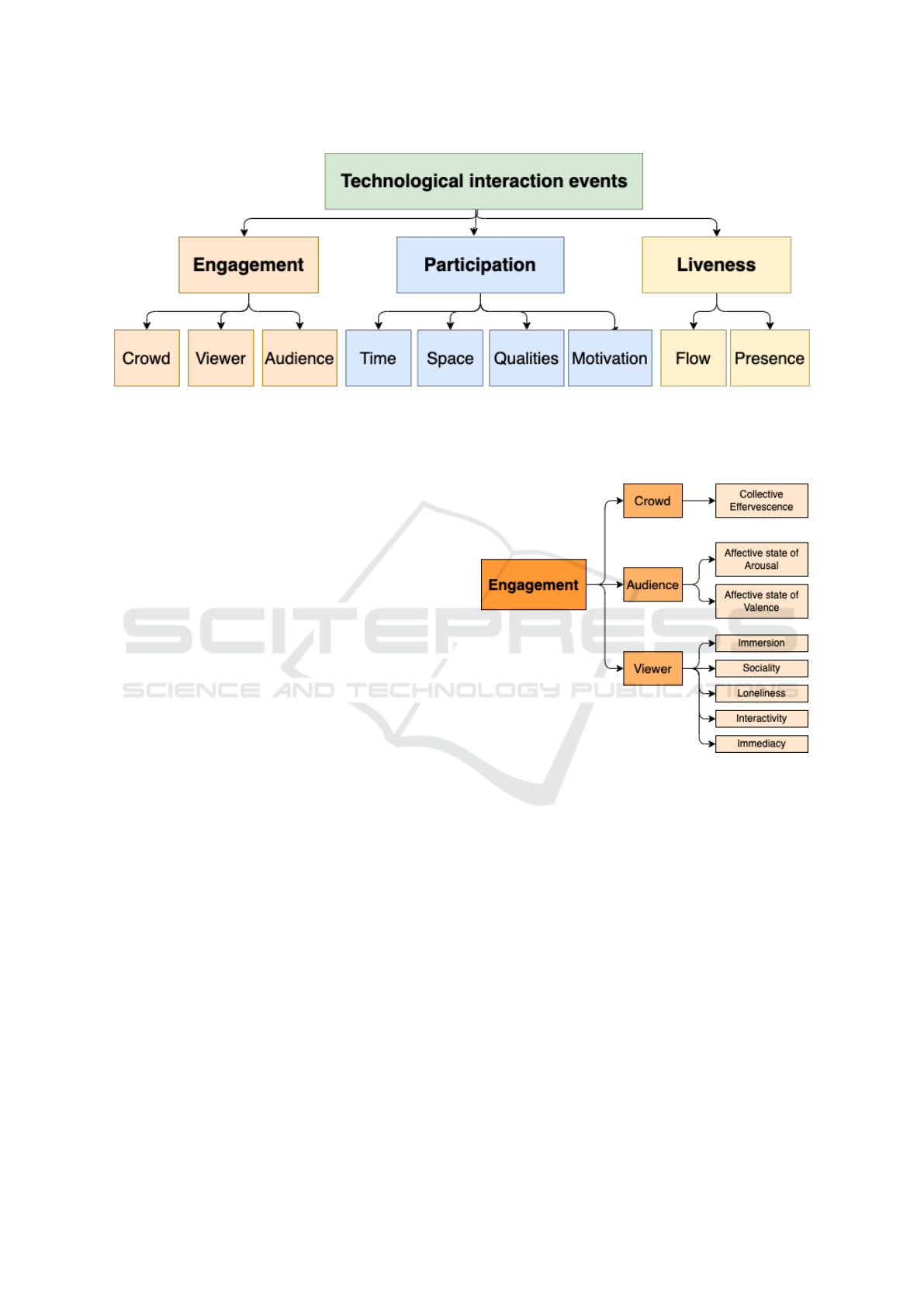

The taxonomy presented in Figure 1 shows the

organization and relationship between the concepts

from three lenses: Engagement, Participation, and

Liveness. The following sections cover each of the

lenses in detail.

1

https://scholar.google.com.br/

2

Supplementary material:

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20001641

3

These papers are also available in the supplementary

material

ICEIS 2023 - 25th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

266

Figure 1: General overview of taxonomy.

3.1 Engagement

The literature points out different concepts for en-

gagement (Doherty and Doherty, 2018). We consider

engagement as “a quality of user experiences with

technology that is characterized by challenge, aes-

thetic and sensory appeal, feedback, novelty, interac-

tivity, perceived control and time, awareness, motiva-

tion, interest, and affect” (O’Brien and Toms, 2008).

Engagement concepts are explored from different

perspectives, such as cognitive, emotional, and behav-

ioral. The cognitive perspective relates to attributes

such as effort, energy, awareness, and attention. The

emotional perspective emphasizes the nature of expe-

rience involving attributes such as identification, be-

longing, values, attitudes, and emotions. The behav-

ioral perspective highlights the action and participa-

tion of the actors involved. Constantly, the concept

of engagement is also associated with phenomena of

immersion, motivation, involvement, and experience

(Doherty and Doherty, 2018).

In the context of technological interaction in

events, Latulipe et al. (2011) define engagement as “a

complex phenomenon that involves both valence and

arousal”. The representation of these concepts can

be seen in Figure 2. Considering the perspective of

technological interaction in events, we organized the

engagement phenomenon based on three unit analy-

ses: Crowd, Audience, and Viewer. These unit anal-

yses synthesize different behaviors, emotions, per-

sonalities and how engagement is affected by tech-

nological interaction at events. In crowd unit anal-

yses, collective engagement is observed from large

masses (Veerasawmy and McCarthy, 2014; Vasconce-

los et al., 2018). In Audience unit analyses, engage-

ment is perceived from smaller audiences, not neces-

sarily characterized as crowds (Latulipe et al., 2011;

Ara

´

ujo et al., 2022; Cerratto-Pargman et al., 2014). In

the Viewer unit analyses, individual experience is ob-

served (Haimson and Tang, 2017), even if the viewer

finds himself participating in an audience or crowd.

Figure 2: Representation of concepts associated with En-

gagement.

3.1.1 Crowd

According to Vasconcelos et al. (2018), Crowd En-

gagement can be understood as ”a branch of crowd

dynamics, but with a focus on how the crowd interacts

with each other or as a group in a given event.” The

authors use this concept to encourage mass partici-

pation, providing public engagement in performances

and art installations, such as applause and cheering.

Crowd Engagement is typical at events with large

masses, such as sporting events or music festivals,

where people collectively come together for a com-

mon goal, such as raising a smartphone flashlight,

cheering, or crowds joining in singing the team’s an-

them. The characteristics of this type of engagement

are associated with the concept of Collective Effer-

vescence (Durkheim and Swain, 2008).

Engagement, Participation, and Liveness: Understanding Audience Interaction in Technology-Based Events

267

Collective Effervescence is a concept that

emerged from psychology and conveyed the idea that

groups gathered in a single place share the feeling

of collective exaltation and emotion. Durkheim and

Swain (2008) describes Collective Effervescence as:

”The very fact of congregating is an exceptionally

powerful stimulant. Once the individuals are gath-

ered together, a sort of electricity is generated from

their closeness and that quickly launches them to an

extraordinary height of exaltation... Probably because

a collective emotion cannot be expressed collectively

without some order that permits harmony and unison

of movement, these gestures and cries tend to fall into

rhythm and regularity”.

In the context of technological interaction in

events, the motivation derived from the interaction of

large masses is one of the Collective Effervescence

effects, especially when there is the possibility of in-

teracting or transmitting their exaltation with the mo-

ment (Otsu et al., 2021), such as flash mobs or crowds

in football stadiums cheering for their team.

In remote events such as live streams, this col-

lective feeling is conveyed differently and can occur

through comments on streaming platforms or other

forms of interaction with the public. Therefore, in re-

mote events, the collective experience is not the same

as in events where the audience can physically inter-

act (Otsu et al., 2021).

Collective sentiment affects emerging aspects in-

fluencing the crowd’s experience, such as imitation

and invention. Imitation is a contagious movement

involving responses from the crowd to participate in

collective behaviors, characterized by moments of

emotion and arousal. In this context, invention is a

phenomenon derived from imitation and refers to the

emergence of new behaviors, such as creating new

songs, dances, or rituals (Veerasawmy and McCarthy,

2014).

The literature brings different perceptions about

behaviors and characteristics associated with Crowd

Engagement. Therefore, it is noted that Crowd En-

gagement is a broad concept with varying points of

view. However, it is necessary to understand how to

design new forms of technological interaction to pro-

mote the crowd’s experience, whether in face-to-face,

virtual or hybrid spaces.

3.1.2 Audience

Mackellar (2013) defines an audience as a group

of listeners or viewers waiting to engage with the

event. This concept of audience is generic and in-

cludes crowds to individual viewers of an event. Thus,

we consider Audience unit analyses as a grouping of

viewers participating in an event. However, this unit

analysis does not include audiences in large masses

(crowds) as a target, but smaller audiences, such as

audiences in theaters or lectures.

In the context of technological interaction, audi-

ence engagement is observed from emotional phe-

nomena such as valence (positive and negative) and

pleasure (Latulipe et al., 2011; Webb et al., 2016).

Latulipe et al. (2011) emphasize that engagement can

be used as a tool to understand how performance is

perceived by the audience and can be an indication

that the audience is engaged in different contexts. In

traditional performances such as theater or opera, si-

lence is an indicator of audience engagement (Webb

et al., 2016).

Engagement is also considered from the perspec-

tive of performances in distributed spaces (Webb

et al., 2016). In game live streamings, engagement

can be observed from audience participation when us-

ing resources made available by the broadcast plat-

form, such as chats (Chen et al., 2019; Friedlander,

2017), likes (Tang et al., 2017; Br

¨

undl and Hess,

2016), emoticons or stickers (Lu et al., 2021; Chen

et al., 2019).

According to Latulipe et al. (2011), audience en-

gagement is presented from an emotional perspective

related to affection and how the audience expresses

their emotions when interacting and participating in

the performance. From this perspective, the affec-

tive states Arousal and Valencia stand out. Valence

is associated with audience attention and interest and

can be measured as positive and negative (Latulipe

et al., 2011). On the other hand, Arousal is related

to emotional intensity (sleepy - activated), and can

be affected by the music or what the viewer observes

around (Latulipe et al., 2011). Besides this, the con-

cept of Arousal is used as a factor to evaluate audience

reaction during a performance (Han et al., 2021).

3.1.3 Viewer

Engagement can be analyzed from the perspective of

an individual following the technological interaction

(Viewer engagement). The Viewer unit analysis rep-

resents the individual experience of a spectator who

may participate in a Crowd or an Audience. The indi-

vidual and collective experiences are distinct. Com-

mon examples occurred during the COVID-19 pan-

demic, where many live streams emerged as an al-

ternative to promote events. In this context, a sin-

gle viewer can be following a live music festival from

home, however, collectively gathered with thousands

of people through the broadcast platform chat or using

social networks (Lessel et al., 2017).

Five dimensions affect viewer engagement: im-

mersion, immediacy, interactivity, sociality (Haim-

ICEIS 2023 - 25th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

268

son and Tang, 2017) and loneliness (McLaughlin

and Wohn, 2021). These dimensions relate to what

makes live streams engaging from the viewer’s per-

spective and explore the limitations that arise from

the interaction between viewer and content trans-

mitter(streamer). Haimson and Tang (2017) and

(McLaughlin and Wohn, 2021) refer to these dimen-

sions in the context of live streams.

Haimson and Tang (2017) describe immersion as

the feeling of being present as part of the experience,

considering factors such as energy, excitement, and

whether you can see and hear the crowd during the

event. In addition, from the different modalities in

which the event is held, the experience can become

more immersive for the spectator and provide a sense

of connectedness with both the performers and audi-

ence Geigel (2017). Unlike immersion, immediacy

is represented by the unpredictable, associated with

aspects in which viewers can perceive what happens

in real-time, such as uncensored content, immedi-

ate responses, and the feeling of not knowing what

might happen next. Interactivity explores behavioral

aspects of the spectator, being concerned with active

or passive states. While a passive viewer watches the

stream, an active viewer uses resources (e.g., chat or

stickers) to interact with the stream or other viewers

(Haimson and Tang, 2017; Br

¨

undl et al., 2017; Striner

et al., 2021). Sociality shares social aspects of par-

ticipation and is perceived when friends or acquain-

tances watch the same broadcast and share the same

experience. For instance, streamers who have friends

watching the broadcast can invite them to be part of

the show, thus promoting engagement (Haimson and

Tang, 2017). Contrary to Sociality, Loneliness is con-

sidered the state of isolation of the viewer, which

happens when one lacks appropriate social partners

to share desired social activities (McLaughlin and

Wohn, 2021).

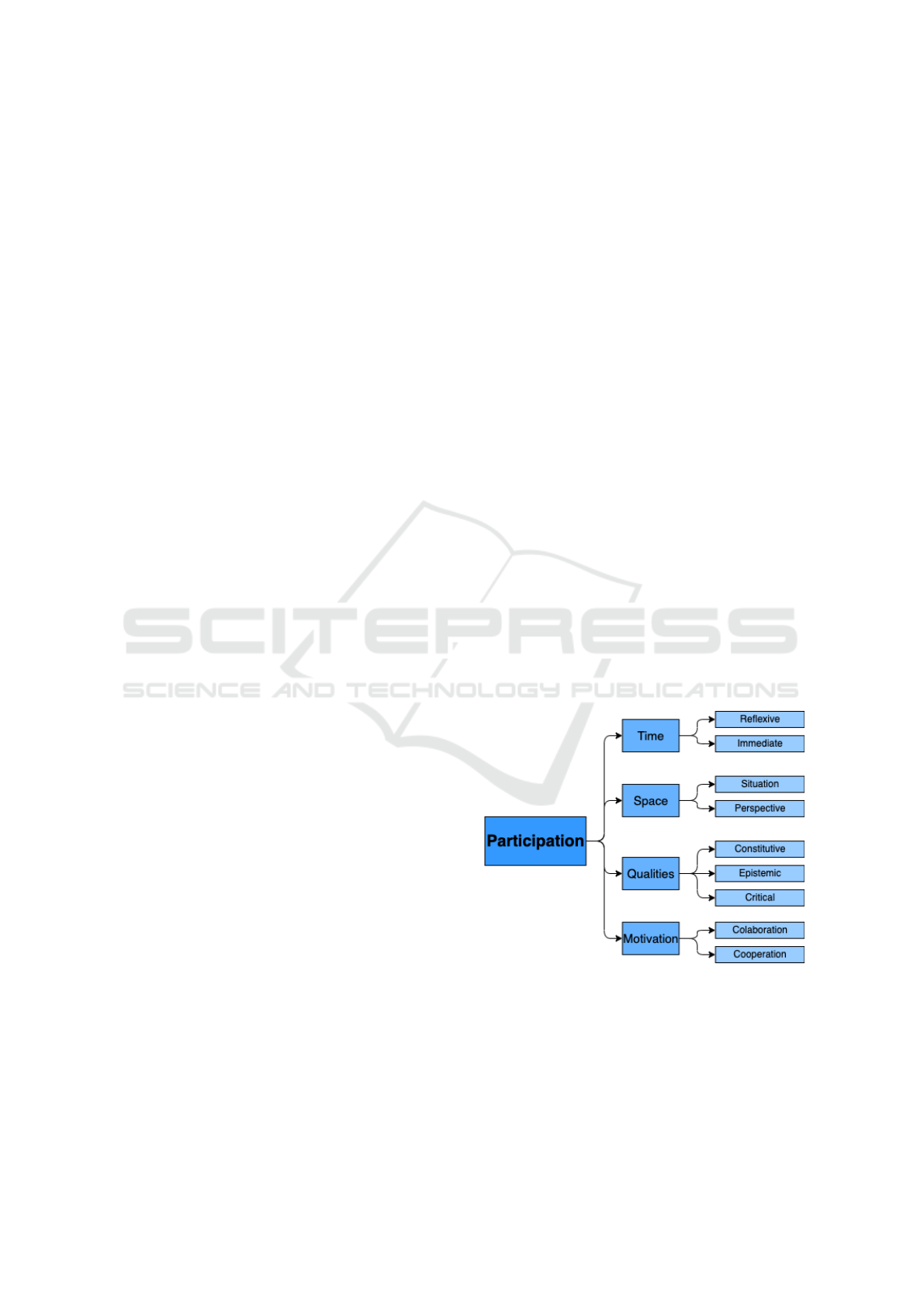

3.2 Participation

Event and audience studies have become prominent

in areas such as tourism (Getz, 2007, 2008), where

audience participation as part of the performance has

become a popular topic. In this sense, audience par-

ticipation is conceptualized from active and passive

behaviors (Mackellar, 2013). Active participation in-

volves energy, enthusiasm, skills, and commitment to

audience resources. Passive participation doesn’t re-

quire many skills and is related to just watching and

following the event (Mackellar, 2013). The represen-

tation of this concept is presented in Figure 3.

Considering events with technological interaction,

Audience participation is a way to engage audiences,

and reinforce the liveness of the experience (Robin-

son et al., 2022). In the literature, audience partic-

ipation is synthesized from active/passive behaviors

(Cerratto-Pargman et al., 2014; Li et al., 2019). Other

works highlight qualities(Cerratto-Pargman et al.,

2014) and motivations(Martins et al., 2021) that in-

fluence audience’s experience through technological

interaction. Participation is constantly used as an

alternative to making events engaging and interac-

tive, as an essential part of interactive performances

(Cerratto-Pargman et al., 2014). Through this partic-

ipation, elements like emotional expressiveness and

interactions between artists and audience members

can emerge from audience participation (Tholander

et al., 2021). In remote events, audience participa-

tion can be performed through features such as chat

and voting (Li et al., 2019). Such interactive features

for audience participation may influence the content

of the broadcast and the content to be broadcast in

the future (Lessel et al., 2017). Consequently, immer-

sion content, the immediacy of audience action, and

the sociality of the experience can be affected (Striner

et al., 2021).

From literature, audience participation by techno-

logical interaction can be analyzed from four perspec-

tives: concerning the time or moment in which it oc-

curs, the environment in which this participation takes

place, the audience’s motivation to participate in the

event, and the qualities of this participation. A rep-

resentation of this perspective can be seen in Figure

3.

Figure 3: Representation of concepts associated with Par-

ticipation.

3.2.1 Time Related Participation

Regarding time as an aspect, participation is char-

acterized by two facets: reflexive and immediate

(Cerratto-Pargman et al., 2014). The reflective facet

reflects the personal participatory experience after the

Engagement, Participation, and Liveness: Understanding Audience Interaction in Technology-Based Events

269

performance. The immediate facet describes emerg-

ing qualities during the show. The authors add that

sensory, emotional, and intellectual stimuli associated

with engagement are awakened from technological

interaction.

From an immediate facet, two concepts were iden-

tified which affect participation with technological in-

teraction during the event: technology-mediated audi-

ence (H

¨

odl et al., 2020) and Co-performance (Li et al.,

2019).

Moreover, we related the immediate facet with

Co-performance concept. Li et al. (2019) refer Co-

Performance as a collaboration between performance,

audiences, and streamers to present performances in

live streaming. In this sense, the authors empha-

size that Co-performance is concerned with how the

streamer and audience interaction occurs and how it

can improve such interaction.

3.2.2 Space Related Participation

Participation integrates elements that affect the expe-

rience, including the space in which the audience is

distributed (Webb et al., 2016).

One concept regarding audience participation is

Perspective. Geigel (2017) refers ’Perspective’ as the

experience of participation related to the venue of the

performance, considering where the audience view

and interact with the performance. Besides this, au-

dience view is related audience’s position in the envi-

ronment, such as the seat of the viewer during the per-

formance. Still, from Perspective, we associated an-

other concept, Intervenability. The concept of Inter-

venability refers first-person perspective, specifically

the sense of being involved in the relationship with

a member (Yakura, 2021). This concept cares about

how members can control the mode of interaction is

conducted.

3.2.3 Participation Qualities

Studies emphasize the need to understand the ex-

perience through audience participation in interac-

tive performances (Williamson et al., 2014; Martins

et al., 2021; Lu, 2021; Striner et al., 2021). Cerratto-

Pargman et al. (2014) explore audience participation

from three emerging qualities: constitutive, epistemic

and critical.

The Constitutive quality seeks to understand par-

ticipation from the cultural and social perspective of

the participants concerning the performance, espe-

cially how they establish themselves to interact or ac-

company the performance (Cerratto-Pargman et al.,

2014). In live stream context, communities can be

considered as members of grups around themes such

as culture and pride. The members has roles and spe-

cific identities where a network of thematic relation-

ships and emotional connection (Striner et al., 2021;

Hilvert-Bruce et al., 2018).

In Epistemic quality, the values of participation

are associated with the experience of knowing more

about oneself, and about others around them during

the performance (Cerratto-Pargman et al., 2014). On

the other hand, Critical quality seeks to understand

the emergence of emerging social issues and critical

thinking about participation (Cerratto-Pargman et al.,

2014). Social aspects can emerge from messages with

a socio-political charge, such as themes related to mi-

norities, wars or social movements (Cerratto-Pargman

et al., 2014). As an example of Critical quality, we can

mention the live streams where performers encourage

the public to express themselves about various top-

ics. The incentive reflects in audience participation

through text comments in chat and the rise of hash-

tags associated with the theme.

3.2.4 Motivation

When designing interactive technologies at events, it

is necessary to observe motivation as a fundamen-

tal factor. Each type of audience may have different

intentions to participate (Gomes et al., 2020). H

¨

odl

et al. (2017) note that the audience wants unique and

special experiences and feels part of an audience. Wu

et al. (2017) suggest that the motivation to participate

is influenced by the desire to be an active spectator

and point out some characteristics that affect audi-

ence motivation, such as imitation, competitiveness,

contributing to the performance, or directing/leading

the performance.

The motivation is the intention to interact and ex-

perience new experiences. Motivation can be asso-

ciated with two main activities presented by Martins

et al. (2021), Collaboration and Competition. Collab-

oration is described as the “process by which people

act together for a common goal, being a collective,

synchronous activity that results from a sustained ef-

fort to build and maintain a shared understanding of

an issue or task” (Martins et al., 2021). Therefore,

motivation is the desire to participate in collective ac-

tivities with common goals. Otherwise, Competition

reflects the intention to participate in competitive ac-

tivities, and motivation is affected by the feeling of

challenge (Martins et al., 2021). Typical examples

are seen at sporting events where audiences are in-

fluenced to cheer for a team.

Therefore, exploring possibilities for participation

can be a challenge where it is necessary to think about

how to design new experiences and study the context

of the event.

ICEIS 2023 - 25th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

270

3.3 Liveness

Liveness represents the connection of people follow-

ing and watching the event in real-time and living the

spontaneity of the experience(Mueser and Vlachos,

2018).

In the context of technological interaction, Webb

et al. (2016) describes the concept of Liveness as:

”experiencing an event in real-time with the potential

for shared social realities among participants”. Hook

et al. (2012) suggests that Liveness is conceived from

aspects of location and presence, as well as attributes

such as space and time (Webb et al., 2016). Besides

this, Liveness is considered a key aspect to captur-

ing the energy of a live performance (Robinson et al.,

2022), related to connection between viewers watch-

ing the same event and the naturalness of the live ex-

perience (Mueser and Vlachos, 2018; Jacobs, 2018).

Therefore, Liveness is associated with the experience

of being there (Hook et al., 2012), and accompanying

the audience by participating in the event (Mueser and

Vlachos, 2018). Liveness is usually used to differenti-

ate live events from recorded events concerning possi-

bilities of interaction and engagement (Geigel, 2017;

Benford et al., 2021; Striner et al., 2021). A repre-

sentation of this perspective can be seen in Figure 4.

We use the term Liveness to represent the whole at-

mosphere that affects the experience of the audience,

as well as sensations and emotions. In this sense,

two concepts are associated with Liveness: Flow and

Presence.

Figure 4: Representation of concepts associated with Live-

ness.

3.3.1 Flow

The Flow represents the phenomenon of being ab-

sorbed and entwined by something (Csikszentmihalyi

and Csikzentmihaly, 1990). In the context of techno-

logical interaction, Mueser and Vlachos (2018) high-

light examples that provoke the state of Flow, such

as engagement and concentration, learning and chal-

lenge, energy and tension, shared experience and at-

mosphere, and personal and connection.

3.3.2 Presence

Unlike Flow, which represents the perception of being

absorbed, Presence is a paradigm concerned with re-

designing Liveness, considering the degree to which

spectators pay attention to the event and intensity of

engagement (Kim, 2017). For instance, in virtual re-

ality events, Presence is used to evaluate the quality of

experience, concerned with the emotional response of

”being there” (Yakura and Goto, 2020). Presence can

be associated with two concepts: Co-presence and

Social Presence.

Haimson and Tang (2017) present the concept of

Co-presence as a ”shared sense of space and time that

bridges the gap between event participants and audi-

ence”. This concept represents how audiences can

be established at the event to interact or follow the

performances. For example, in environments with

physical Co-presence, participants can socially inter-

act with (Webb et al., 2016; Geigel, 2017) audience

members. In remote or virtual spaces, this concept is

important to engage remote audiences and promote

liveness (Otsu et al., 2021), and can be associated

with audiences chatting in a shared chat(Webb et al.,

2016).

Social Presence is related to the degree of aware-

ness of others in an interaction (Geigel, 2017), con-

cerning how people present in the same space coexist

and react with other viewers (Li et al., 2020). Geigel

(2017) points to factors between audience members,

such as their verbal and non-verbal communication

and the feeling of shared simultaneous experience in

the same environment.

Sharing the same environment and reactions with

audiences can awaken new feelings. In virtual and re-

mote environments, there’s the Sense of Unity. This

concept is described as a consequence of the synergic

effect among audience excitement, such as cheering

or shouting reactions (Yakura and Goto, 2020). Sense

of Unity is also described as unique interaction be-

tween the audiences and the performers (Abe et al.,

2022). Additionally, the Sense of Belonging is one

of the reasons viewers interact during remote events.

This concept is related to community relationships,

considering emotional dependence on the group and

how users interact in these communities (Li and Guo,

2021).

4 DISCUSSION

In this literature review, we sought answers to the fol-

lowing research question: How researches in HCI

and CSCW areas are approaching technological in-

Engagement, Participation, and Liveness: Understanding Audience Interaction in Technology-Based Events

271

teraction in events? Therefore, the concepts derived

from the literature were organized into a taxonomy

structured around three major concepts, here consid-

ered lenses of analysis: engagement, participation and

liveness.

Regarding HCI, the review frequently addresses

issues associated with live streaming. Researchers

are concerned with how to increase audience inter-

action and engagement with the streamer of the con-

tent (Tang et al., 2016; Fraser et al., 2019), which

makes experiences in live streaming engaging (Haim-

son and Tang, 2017). Interaction happens in many

ways, such as chat, likes, polls, or other interactive

features (Striner et al., 2021; Miller et al., 2017). An-

other concept related to live streaming is associated

with liveness since the consumption of content after

the live broadcast makes the experience different from

when performed live (Benford et al., 2021). View-

ers appreciate raw content, and value real-time inter-

action (Lu et al., 2018). For instance, lives that oc-

curred during the pandemic, although it has already

happened, the recording is available to be watched on

video-sharing platforms.

It’s important to consider keeping viewers moti-

vated and engaged in live streaming. Viewers interact

with each other or with the broadcaster. This inter-

action has the potential to change the content during

the live. Therefore, it is necessary to explore opportu-

nities from the viewers’ perspective, provide alterna-

tives to remain engaged, identify how they can change

the broadcast, and generate new interactive resources.

Outside the context of live streaming, there were

studies related to concepts of collective effervescence

in live music performances (Otsu et al., 2021) and au-

dience participation by music creation (H

¨

odl et al.,

2020).

In CSCW, studies address how liveness experi-

ences are transformed by technology into distributed

performances (Webb et al., 2016), how participants

are collaborating in virtual spaces (Wallace et al.,

2020; Ara

´

ujo et al., 2022) and different forms of inter-

action and participation in live streamings (Lu et al.,

2021; Li et al., 2019; Tang et al., 2017). For the

CSCW community, it is interesting to explore audi-

ence participation in live streams, as, in many live

streams, the audience is encouraged to work together

for common goals, such as raising funds for a cam-

paign and collaborating to solve challenges in games,

for instance.

From these works, there is a growing demand for

research with interest in understanding audiences’ ex-

perience in live broadcasts. Therefore, promoting al-

ternatives to increase interaction and participation in

live broadcasts are trending topics in these areas.

The taxonomy proposed is based on three main

lenses (Engagement, Participation and Liveness).

When analyzing aspects of engagement, it is natural

to observe aspects of audience participation and live-

ness, in the same way, when investigating liveness,

aspects of engagement and participation emerge since

such concepts have an intrinsic relationship with each

other. For example, an audience may attend a remote

event and engage actively with the provided technol-

ogy interaction. Consequently, when designing forms

of technological interaction, it is important to con-

sider the experience as a whole without losing focus

on the individual experience that participates in the

interaction.

Considering engagement as an emotional, cogni-

tive, and behavioral phenomenon (Doherty and Do-

herty, 2018), participation as a result of technological

interaction can arouse different levels of engagement,

that is, feelings that represent the experience. Such

feelings are presented in different ways, as presented

in the Subsection 2.1. This experience is affected

by the feeling of being there experiencing the expe-

rience and the immediacy represented by the concept

of Liveness.

Studies already propose alternatives to measure

audience engagement during events(Wang et al.,

2014; Latulipe et al., 2011). However, it needs atten-

tion since, while they seek to measure engagement,

they can also affect the audience’s experience as a

technology user. Interactive features in live streaming

can also affect the remote event experience. Text mes-

sages can be useful when interacting with audiences

or small crowds. However, when the audience grows

exponentially, it becomes difficult to manage the flow

of messages (Miller et al., 2017; Haimson and Tang,

2017). Therefore, there is a need to think about how to

explore these concepts in order to minimize difficul-

ties faced when providing experiences derived from

technological interaction in events, as Haimson and

Tang (2017) suggest message flow groupings in chat.

In this sense, the HCI area can contribute by ob-

serving how to promote and improve interactive ex-

periences based on new resources and technologies.

However, it is necessary to explore different modali-

ties, events, and audiences considering different con-

texts. Such concepts help assess how the experience

expected by technological interaction is affected by

the performance and how audience interaction is af-

fected. In this context, this is a topic to be explored, as

event producers seek to provide unique experiences to

the public, improving their involvement and engage-

ment. As a result, opportunities can be explored to

contribute to the experience, in particular, improve

the UX of technologies or study how can apply In-

ICEIS 2023 - 25th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

272

teraction Design to design products aimed at public

participation and engagement.

The CSCW area, on the other hand, can contribute

to exploring how audiences collaborate to achieve

common goals. It is noted that several aspects are to

be explored, such as remote, face-to-face, or hybrid

audiences. Therefore, how the audience and show

collaborate is essential to transform experiences lived

during the event and audience motivations to collabo-

rate.

This research contributes to the taxonomy of con-

cepts related to technological interaction in events

found in the literature. Those concepts have the po-

tential to introduce novel perspectives for engage-

ment across varying contexts and modes of occur-

rence, including frameworks or models that serve as

a foundation for comprehending and interpreting the

technology-mediated phenomenon or process. This,

in turn, may facilitate the advancement of technolo-

gies pertaining to said phenomenon or process. How-

ever, they need to be explored carefully since, in the

same way that experiences provide positive feelings

about the interaction, negative perceptions must also

be considered.

5 CONCLUSION

This paper presented a taxonomy of concepts asso-

ciated with technological interaction in events with

the potential to provide new audience experiences.

The organization of concepts was derived from an

exploratory literature review using backward and for-

ward snowballing techniques. As a result, three main

concepts were identified: Engagement, Participation

and Liveness.

These concepts were associated with a unit analy-

sis that helps to characterize ways of promoting tech-

nological interaction. As a result, we verified how en-

gagement could be observed from different perspec-

tives. In addition, we highlight how the audience can

be motivated to participate and the importance of their

real-time experience.

Understanding the concepts presented can change

the experience mediated by technological interaction,

considering different modalities of the event. This

representation aims to obtain an overview of concepts

that affect the experience. In future work, we aim to

validate this taxonomy through a study with special-

ists and investigate how to design technologies con-

sidering the association of all concepts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank USES Research Group members for their

support. The present work is the result of the Re-

search and Development (R&D) project 001/2020,

signed with Federal University of Amazonas and

FAEPI, Brazil, which has funding from Samsung, us-

ing resources from the Informatics Law for the West-

ern Amazon (Federal Law nº 8.387/1991), and its dis-

closure is in accordance with article 39 of Decree No.

10.521/2020. Also supported by CAPES - Financing

Code 001, CNPq process 314174/2020-6, FAPEAM

process 062.00150/2020, and grant 2020/05191-2

Sao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP).

REFERENCES

Abe, M., Akiyoshi, T., Butaslac, I., Hangyu, Z., and

Sawabe, T. (2022). Hype live: Biometric-based sen-

sory feedback for improving the sense of unity in vr

live performance. In 2022 IEEE Conference on Virtual

Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Work-

shops (VRW), pages 836–837. IEEE.

Ara

´

ujo, C. G., Martins, G., Gomes, G., Kienen, J. G.,

de Freitas, R., Castro, T., and Gadelha, B. (2022). Cof-

fee break virtual: uma experi

ˆ

encia musical interativa

e colaborativa. In Anais do XVII Simp

´

osio Brasileiro

de Sistemas Colaborativos, pages 132–145. SBC.

Benford, S., Mansfield, P., and Spence, J. (2021). Producing

liveness: The trials of moving folk clubs online during

the global pandemic. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems,

pages 1–16.

Br

¨

undl, S. and Hess, T. (2016). Why do users broadcast?

examining individual motives and social capital on so-

cial live streaming platforms.

Br

¨

undl, S., Matt, C., and Hess, T. (2017). Consumer use

of social live streaming services: The influence of co-

experience and effectance on enjoyment. pages (pp.

1775–1791).

Cerratto-Pargman, T., Rossitto, C., and Barkhuus, L.

(2014). Understanding audience participation in an

interactive theater performance. In Proceedings of the

8th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interac-

tion: Fun, Fast, Foundational, pages 608–617.

Chen, D., Freeman, D., and Balakrishnan, R. (2019). Inte-

grating multimedia tools to enrich interactions in live

streaming for language learning. In Proceedings of the

2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Comput-

ing Systems, pages 1–14.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. and Csikzentmihaly, M. (1990).

Flow: The psychology of optimal experience, volume

1990. Harper & Row New York.

de Freitas Martins, G., de Freitas, R., and Gadelha, B.

(2020). A mobile game based on participatory sens-

ing with real-time client-server architecture for large

Engagement, Participation, and Liveness: Understanding Audience Interaction in Technology-Based Events

273

entertainment events. In 2020 XLVI Latin Ameri-

can Computing Conference (CLEI), pages 332–339.

IEEE.

Doherty, K. and Doherty, G. (2018). Engagement in hci:

conception, theory and measurement. ACM Comput-

ing Surveys (CSUR), 51(5):1–39.

Durkheim, E. and Swain, J. W. (2008). The elementary

forms of the religious life. Courier Corporation.

Fraser, C. A., Kim, J. O., Thornsberry, A., Klemmer, S., and

Dontcheva, M. (2019). Sharing the studio: How cre-

ative livestreaming can inspire, educate, and engage.

In Proceedings of the 2019 on Creativity and Cogni-

tion, pages 144–155.

Friedlander, M. B. (2017). Streamer motives and user-

generated content on social live-streaming services.

Journal of Information Science Theory and Practice,

5(1):65–84.

Geigel, J. (2017). Creating a theatrical experience on a vir-

tual stage. In International Conference on Advances

in Computer Entertainment, pages 713–725. Springer.

Getz, D. (2007). Event studies: Theory, research and policy

for planned events.

Getz, D. (2008). Event tourism: Definition, evolution, and

research. Tourism management, 29(3):403–428.

Getz, D. and Page, S. (2016). Event studies: Theory, re-

search and policy for planned events. Routledge.

Gomes, G., de Freitas, R., Castro, T., and Gadelha, B.

(2020). Interaheu: heuristics for technological inter-

action on events. In Proceedings of the 19th Brazilian

Symposium on Human Factors in Computing Systems,

pages 1–6.

Haimson, O. L. and Tang, J. C. (2017). What makes

live events engaging on facebook live, periscope, and

snapchat. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI conference

on human factors in computing systems, pages 48–60.

Han, J., Chernyshov, G., Sugawa, M., Zheng, D., Hynds,

D., Furukawa, T., Padovani, M., Minamizawa, K.,

Marky, K., Ward, J. A., et al. (2021). Linking audi-

ence physiology to choreography. ACM Transactions

on Computer-Human Interaction.

Hilvert-Bruce, Z., Neill, J. T., Sj

¨

oblom, M., and Hamari, J.

(2018). Social motivations of live-streaming viewer

engagement on twitch. Computers in Human Behav-

ior, 84:58–67.

H

¨

odl, O., Bartmann, C., Kayali, F., L

¨

ow, C., and Purgath-

ofer, P. (2020). Large-scale audience participation in

live music using smartphones. Journal of New Music

Research, 49(2):192–207.

H

¨

odl, O., Fitzpatrick, G., Kayali, F., and Holland, S. (2017).

Design implications for technology-mediated audi-

ence participation in live music.

Hook, J., Schofield, G., Taylor, R., Bartindale, T., Mc-

Carthy, J., and Wright, P. (2012). Exploring hci’s

relationship with liveness. In CHI’12 Extended Ab-

stracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems,

pages 2771–2774.

Jacobs, N. (2018). Live streaming as participation: A case

study of conflict in the digital/physical spaces of su-

pernatural conventions. Transformative Works and

Cultures, 28.

Johnny Allen, William O’Toole, R. H. I. M. (2010). Festival

and Special Event Management, 5th Edition. Wiley

Global Education.

Kim, S.-Y. (2017). Liveness: Performance of ideology and

technology in the changing media environment. In

Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature.

Kitchenham, B. A., Budgen, D., and Brereton, P. (2015).

Evidence-based software engineering and systematic

reviews, volume 4. CRC press.

Latulipe, C., Carroll, E. A., and Lottridge, D. (2011). Love,

hate, arousal and engagement: exploring audience re-

sponses to performing arts. In Proceedings of the

SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing

systems, pages 1845–1854.

Lessel, P., Mauderer, M., Wolff, C., and Kr

¨

uger, A. (2017).

Let’s play my way: Investigating audience influence

in user-generated gaming live-streams. In Proceed-

ings of the 2017 ACM International Conference on In-

teractive Experiences for TV and Online Video, pages

51–63.

Li, J., Gui, X., Kou, Y., and Li, Y. (2019). Live streaming

as co-performance: Dynamics between center and pe-

riphery in theatrical engagement. Proceedings of the

ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 3(CSCW):1–

22.

Li, L., Uttarapong, J., Freeman, G., and Wohn, D. Y. (2020).

Spontaneous, yet studious: Esports commentators’

live performance and self-presentation practices. Pro-

ceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interac-

tion, 4(CSCW2):1–25.

Li, Y. and Guo, Y. (2021). Virtual gifting and danmaku:

What motivates people to interact in game live stream-

ing? Telematics and Informatics, 62:101624.

Lu, Z. (2021). Understanding and Supporting Live Stream-

ing in Non-Gaming Contexts. PhD thesis, University

of Toronto (Canada).

Lu, Z., Kazi, R. H., Wei, L.-Y., Dontcheva, M., and Kara-

halios, K. (2021). Streamsketch: Exploring multi-

modal interactions in creative live streams. Proceed-

ings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction,

5(CSCW1):1–26.

Lu, Z., Xia, H., Heo, S., and Wigdor, D. (2018). You watch,

you give, and you engage: a study of live streaming

practices in china. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI

conference on human factors in computing systems,

pages 1–13.

Mackellar, J. (2013). Event Audiences and Expectations.

Routledge advances in event research series. Rout-

ledge.

Martins, G., Gomes, G., Conceic¸

˜

ao, J. L., Marques, L.,

da Silva, D., Castro, T., Gadelha, B., and de Freitas,

R. (2021). Bumbometer digital crowd game: collab-

oration through competition in entertainment events.

Journal on Interactive Systems, 12(1):294–307.

Martins, G., Gomes, G., Conceic¸

˜

ao, J. L., Marques, L.,

Silva, D. d., Castro, T., Gadelha, B., and de Freitas,

R. (2020). Enhanced interaction: audience engage-

ment in entertainment events through the bumbometer

app. In Proceedings of the 19th Brazilian Symposium

on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages 1–9.

ICEIS 2023 - 25th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

274

McLaughlin, C. and Wohn, D. Y. (2021). Predictors of

parasocial interaction and relationships in live stream-

ing. Convergence, 27(6):1714–1734.

Miller, M. K., Tang, J. C., Venolia, G., Wilkinson, G., and

Inkpen, K. (2017). Conversational chat circles: Being

all here without having to hear it all. In Proceedings of

the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Com-

puting Systems, pages 2394–2404.

Mueser, D. and Vlachos, P. (2018). Almost like being there?

a conceptualisation of live-streaming theatre. Interna-

tional Journal of Event and Festival Management.

O’Brien, H. L. and Toms, E. G. (2008). What is user en-

gagement? a conceptual framework for defining user

engagement with technology. Journal of the Ameri-

can society for Information Science and Technology,

59(6):938–955.

Otsu, K., Yuan, J., Fukuda, H., Kobayashi, Y., Kuno, Y., and

Yamazaki, K. (2021). Enhancing multimodal interac-

tion between performers and audience members dur-

ing live music performances. In Extended Abstracts of

the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Com-

puting Systems, pages 1–6.

Robinson, R. B., Rheeder, R., Klarkowski, M., and

Mandryk, R. L. (2022). ” chat has no chill”: A novel

physiological interaction for engaging live streaming

audiences. In CHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems, pages 1–18.

Striner, A., Webb, A. M., Hammer, J., and Cook, A. (2021).

Mapping design spaces for audience participation in

game live streaming. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems,

pages 1–15.

Tang, J., Venolia, G., Inkpen, K., Parker, C., Gruen, R., and

Pelton, A. (2017). Crowdcasting: Remotely partic-

ipating in live events through multiple live streams.

Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Inter-

action, 1(CSCW):1–18.

Tang, J. C., Venolia, G., and Inkpen, K. M. (2016). Meerkat

and periscope: I stream, you stream, apps stream for

live streams. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI confer-

ence on human factors in computing systems, pages

4770–4780.

Tholander, J., Rossitto, C., Rostami, A., Ishiguro, Y.,

Miyaki, T., and Rekimoto, J. (2021). Design in ac-

tion: Unpacking the artists’ role in performance-led

research. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference

on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages 1–13.

Vasconcelos, V., Amazonas, M., Castro, T., Freitas, R., and

Gadelha, B. (2018). Watch or immerse? redefining

your role in big shows. In Proceedings of the 17th

Brazilian Symposium on Human Factors in Comput-

ing Systems, pages 1–9.

Veerasawmy, R. and McCarthy, J. (2014). When noise

becomes voice: designing interactive technology

for crowd experiences through imitation and inven-

tion. Personal and ubiquitous computing, 18(7):1601–

1615.

Wallace, S., Le, B., Leiva, L. A., Haq, A., Kintisch,

A., Bufrem, G., Chang, L., and Huang, J. (2020).

Sketchy: Drawing inspiration from the crowd. Pro-

ceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interac-

tion, 4(CSCW2):1–27.

Wang, C., Geelhoed, E. N., Stenton, P. P., and Cesar, P.

(2014). Sensing a live audience. In Proceedings of the

SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing

Systems, pages 1909–1912.

Webb, A. M., Wang, C., Kerne, A., and Cesar, P. (2016).

Distributed liveness: Understanding how new tech-

nologies transform performance experiences. In Pro-

ceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-

Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing,

pages 432–437.

Whittaker, M. and Breininger, K. (2008). Taxonomy devel-

opment for knowledge management.

Williamson, J. R., Hansen, L. K., Jacucci, G., Light, A.,

and Reeves, S. (2014). Understanding performative

interactions in public settings.

Wu, Y., Zhang, L., Bryan-Kinns, N., and Barthet, M.

(2017). Open symphony: Creative participation for

audiences of live music performances. IEEE Multi-

Media, 24(1):48–62.

Yakura, H. (2021). No more handshaking: How have covid-

19 pushed the expansion of computer-mediated com-

munication in japanese idol culture? In Proceedings

of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems, pages 1–10.

Yakura, H. and Goto, M. (2020). Enhancing participation

experience in vr live concerts by improving motions

of virtual audience avatars. In 2020 IEEE Interna-

tional Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality

(ISMAR), pages 555–565. IEEE.

Yang, S., Lee, C., Shin, H. V., and Kim, J. (2020). Snap-

stream: Snapshot-based interaction in live streaming

for visual art. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Confer-

ence on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages

1–12.

Engagement, Participation, and Liveness: Understanding Audience Interaction in Technology-Based Events

275