ALARP in Engineering: Risk Based Design and CBA

Emin Alakbarli

a

, Mohammad Mehdi Hamedanian and Massimo Guarascio

Department of Civil, Constructional and Environmental Engineering, Sapienza University, Rome, Italy

Keywords: ALARP, CBA, Risk, Acceptability, Tolerability, Practicality, Reasonability.

Abstract: It has not been far, over a century, since humankind conceived that hazardous incidents should be substantially

managed to procrastinate the future could-be hazards. In the middle of the twentieth century, nonetheless,

safety measures were passed by officials and introduced to authorities, and private sectors, so as to reduce

risks, environmental impacts of the hazards and to evaluate probable outcomes. Therefore, the concept of

ALARP, meaning ‘as low as reasonably practicable’ presented back then, has been implemented in risk

reduction management to make decisions upon acceptability and tolerability of risks. In order to do so, a few

so-called tools, such as Cost-Benefit Analysis, are specified to societal and other types of risks so that we

could weigh the balance of the amount of capital to be invested on safety on the one hand, and the extracted

benefit attained out of the investment on the other. This implementation opaquely carries on several social,

socio-economic, political and even environmental implications. Nevertheless, it has brought up some

concerns into proponents’ mindset, ranging from practicality and political reality to calling into question

whether ALARP is mainly theoretical. The aim of this study is to figure out whether Cost-Benefit Analysis

can be an appropriate tool to analyse the true outcome(s) of ALARP. This paper will offer a critical point of

view over the risk-evaluating concept to discern how much it has been practically efficient.

1 INTRODUCTION

Fire safety experts aim to bring the risk of fire

incidents to an acceptable level of safety, or as low as

reasonably practicable (ALARP). The concept of

ALARP in accordance with monetizing methods like

Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) has been ubiquitously

utilized by a vast range of industries, from nuclear

power and chemical industries to railway and road

constructions. Therefore, managing risk has been the

main topic, having thorough effect on the mindset of

legislators, private investors and engineers. Being one

of the introduced methods to keep risks under control,

ALARP has not been inveighed a lot since it has been

deemed as an efficient approach to regulate hazardous

activities (Melchers, 2001). Having said that, along

with CBA, it has been used to perceive the amount of

cost and its correlation to benefits afterwards. While

ALARP is reported to be qualitative, holistic and

based on principles, which does not necessarily

represent all-the-same “predictable outcomes”, CBA

is conceived to be quantitative, limited, and acutely

defined (Ale et al., 2015). In other words, the former

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6398-4532

might bring us unequal, subjective decisions, along

with uncertainties and unpredictability in decision

making. The latter, whereas, is accepted to be

objective, working where monetization matters. At

first glance, they might be deemed explicitly separate;

however, they are implicitly correlated in a decision-

making process.

Utilization of ALARP is firstly based on the levels

of risk it works on. Melchers (2001) divided risks into

four levels: negligible risk, acceptable risk, ALARP

region, and unacceptable region of risk. As it is shown

in the Melchers’s (2001) figure, the higher we move,

the more probability of incident and the greater

number of casualties and fatalities we have. In

ALARP, risks should be mitigated to the least level

of tolerability, with the probability of 10

per year

(Figure 1). Then, risks must be reduced and go

towards the level of acceptability provided that it is

said to be reasonably practical.

In Italy, the model of ALARP corresponds to road

tunnels and starts at Tolerability Limit 𝐺

(

𝑁=1

)

−

10

per year and ends at Acceptability Limit

𝐺

(

𝑁=1

)

−10

per year. Above 10

there is

“Not Acceptable Area” which cannot be authorized.

Alakbarli, E., Hamedanian, M. and Guarascio, M.

ALARP in Engineering: Risk Based Design and CBA.

DOI: 10.5220/0011947600003485

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Complexity, Future Information Systems and Risk (COMPLEXIS 2023), pages 61-68

ISBN: 978-989-758-644-6; ISSN: 2184-5034

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

61

Figure 1: Risk levels and ALARP Model numbers of Italian road tunnels.

As it is illustrated in Figure 1, this area starts from

the red line, which plays the role of a threshold for

unacceptability of risk. Below 10

“Negligible

Area” is located, explaining that it is unimportant as

to be not worth the cost in order to be considered. The

area between the Tolerability and Acceptability Limit

zones is the ALARP zone. Here, engineers are called

to make a decision on whether further reduction of

risk is needed, weighing up two components:

decrease in risk and cost of such an operation. Based

on the figure, when the risk becomes higher, the

probability of tunnel accidents with fatalities rises

during the year as well, and the expected number of

fatalities E(N) will increase proportionally to the

width of the triangle in the model.

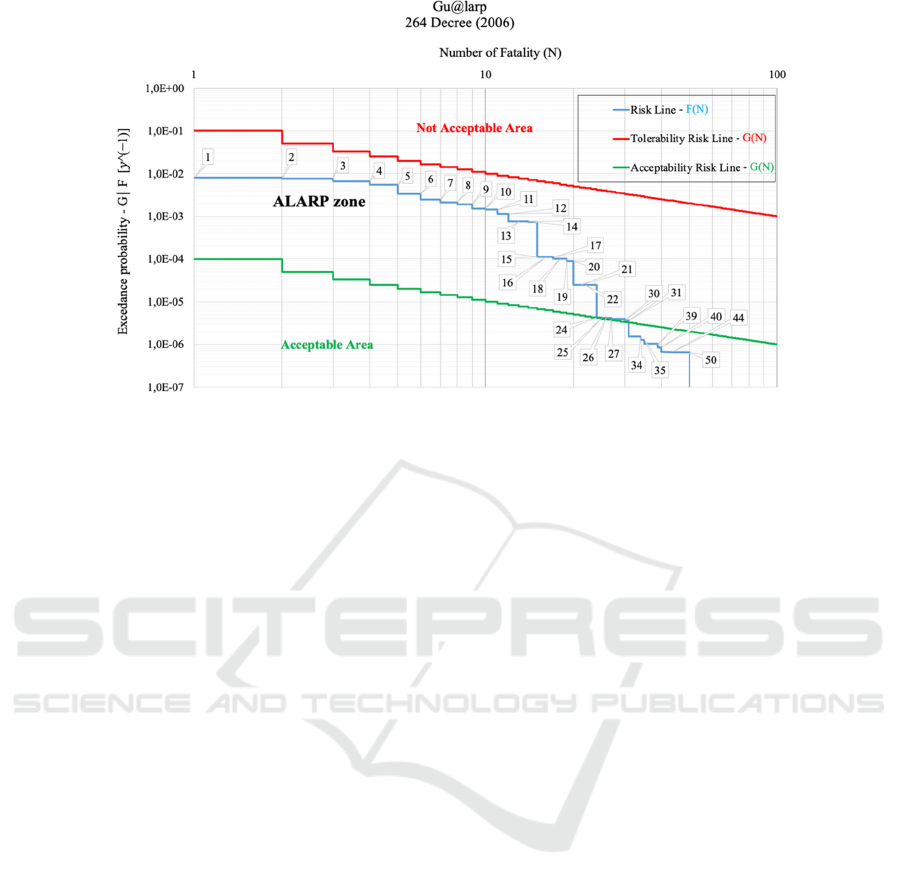

Guarascio (2008, 2021) and Guarascio et al. (2022)

discussed the three levels of safety in ALARP,

comparing and interpreting the concept in Italy. They

also grouped safety levels into three: not acceptable

area, acceptable area and the area between the two,

the ALARP zone which is visually illustrated in

Figure 2. Moreover, in the topic of tunnel safety we

also ought to deal with the number of fatalities (N)

which must be an integer, as it is shown in the

horizontal axis. The corresponding exceedance

probability distribution G(N) or F(N) per year – (For

a given number of fatalities, different scenarios may

occur having the same number of fatalities) is

illustrated on the vertical axis and the “Risk Line”

represents both fatalities and exceedance probability

corresponding to the specific different scenarios. The

fatalities have an indicator but the scenario is

nonempirically observable (true occurrence). Why do

we consider this scenario? It is the only tool that we

have in order to measure the risk. In order to do so,

we have to imagine what could happen and

probabilize that. We should be able to calculate

whatever initial conditions and hypotheses we

assume, and we have to calculate the consequences in

terms of quantitativeness, mathematics, probabilities

and fatalities. Therefore, the Risk Line is not a

straight one in design, it is an irregular staircase line

with different elevations and measurements of the

height, corresponding to the probabilities of

scenarios. Together with the model, it indicates the

procedure to compare the design curve and the model.

CBA can be carried on properly provided that there is

a proper procedural comparison between the design

curve characterizing factors (Risk quanta of

scenarios: probabilized fatalities) and similar factors

in the models. In 2004, the European Parliament

published the DIRECTIVE 2004/54/EC and reflected

the minimum level of safety measures for risk

management. Notwithstanding, it has been pointed

out that the minimum safety measures could be not

fruitful in terms of efficiency and results. Thereafter,

they modified the term to “minimum and sufficient

level of measures” in safety design.

The Required “Minimum Mandatory” in EU

Directive 2004/54/EC (Required “Sufficient

Mandatory” in Italy, Decreto Legislativo n° 264 del 5

Ottobre 2006) or MMRs in the assessment of tunnel

risk is the functions of: a) length of the tunnel (L), b)

traffic Congestion (V), and c) the share(percentage)

of heavy vehicles (HV). This function is shown in

“Equation (1)”:

MM

R

=

f

(L, V, HV

)

(1)

The Level of Safety is proportional to (L), (V) and

(HV). Why is the proportionality needed? It is

COMPLEXIS 2023 - 8th International Conference on Complexity, Future Information Systems and Risk

62

Figure 2: ALARP model, Italian road tunnels regulations (Guarascio et al., 2022).

necessary to establish the type and the cost. The type,

its number and the cost for the protection systems are

then proportional to (L), (V), (HV) and consequently

inversely proportional to the Risk. As the length of

the tunnel, vehicle volume and danger of the vehicles

increase, the cost of protection system also surges up.

Cost means protection and Risk means the probability

of an individual turning into a fatality. We need a

conceptual and mathematical tool to produce this

effect and ALARP model is the answer.

Abrahamsen et al. (2017) believed that risk is

initially expected to be lower than intolerable risk,

which has the aforementioned probability. They also

pointed out that negligible risk has to be differentiated

from other types of risk due to lack of concerns it has

for individuals and the public. Then, risk reduction

measures could be applied between these two regions,

to the region of “tolerability” in ALARP principles

(ALARP zone). Some countries have more restrictive

limits for these two thresholds. For example, the

Netherlands and Italy have stricter outlook than the

United Kingdom.

In general, all risks are expected to be as low as

possible, whether the implementation of safety

measures is costly or not. Thus, there must be a

balance between the cost of risk mitigation strategies

and the benefits attained after safety investments.

Nonetheless, investment of capitals must be targeted

since the safety resources are strictly limited. In order

to do so, how much money should be spent and how

this amount of money is identified? Admittedly,

ALARP correlates the technological side of the risk

to the societal views of that. But what is the role of

the society in this concept? Also, societal risks are

totally subjective or it can be objective as well? These

are the questions that will be addressed in this paper.

2 EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT

AND SAFETY

The directive of EU Parliament (2004) aims at

“ensuring a minimum level of safety for road users in

tunnels in the Trans-European Road Network by the

prevention of critical events that may endanger

human life, the environment and tunnel installations,

as well as by the provision of protection in case of

accidents”. They insist on application of the directive

to all tunnels in the network with the length of 500

meter and above. By the length of the tunnel they

mean the longest traffic lane measured on the fully

enclosed part of the tunnel (Articles 1 and 2). In

addition, while dealing with safety measures in

Article 3, EU parliament pointed out that all safety

measures should be “demonstrated through a risk

analysis in conformity with the provision of “risk

analysis” in Article 13. Thus, all EU members must

admit risk reduction measures an alternative in

implementation of risk measures and “provide the

justification” as well.

Tunnel manager could be a public or private body

who is responsible for the management of tunnels,

providing an incident report for each occurred

accident in the undertaken tunnel (Article 5). One of

the positive points about the Directive (Article 13) is

the fact that one-off and periodic risk analyses

“should” be carried out by a functionally independent

body from the tunnel manager. The “should”

ALARP in Engineering: Risk Based Design and CBA

63

vocabulary, however, is questionable here since it

might be more appropriate to be replaced with

“must”.

While Italy believe that the sufficient level of

safety, which is considered higher than minimum,

shall be applied to tunnels in roads and rail networks

in Europe, EU Directive - in Annex 1 referred to

Article 3 - stated the well-known “minimum level of

safety” for all tunnels. The table within the EU

Directive provides an informative summary of the

minimum requirements. The salient safety measures

are: emergency walkways, exit(s), and crosswalks,

drainage for flammable and toxic gases, resistance of

fire, ventilation and water supply, monitoring system

and communication system.

3 ALARP

The concept of ALARP entails three fundamental

vocabularies: low, reasonable and practicable. The

first time reasonable and practicable measures were

used in regulations dates back to the beginning of the

twentieth century in the United Kingdom in the 1908

Electricity Regulations and in the 1905 self-acting

Mules Regulations. There is even trace of these two

terms in the Fishery industry in 1861. Nevertheless, it

was in 1949, when a rock boulder fell over one

national coal board worker, Mr. Edwards, in a coal

mine causing him to lose his life, that ALARP was

then enshrined in the court of law (NN, 1949), where

Lord Asquith stated that:

“Reasonably practicable” is a narrower term than

“physically possible” and seems to me to imply that a

computation must be made by the owner in which

quantum of risk is placed on one scale and the

sacrifice involved in the measures necessary for

averting the risk (whether in money, time or trouble)

is placed in the other; and if it be shown that there is

a gross disproportion between them, the risk being

insignificant in relation to the sacrifice – the [person

on whom the duty is laid] discharges the onus on them

[of proving that compliance was not reasonably

practicable].”

This statement in the court of law indicated that

whenever one is applying safety measures, they ought

to boost the measures up to a point where there is a

“gross disproportion” between the risks and the costs

of risk mitigation (Van Coile et al., 2019; Ale et al.,

2015; Alakbarli et al., 2023).

After the official introduction of the acronym

ALARP, it was in the 1950s when ALAP (as low as

practicable) was instead used in the US in the field of

radiation protection. Afterwards, it was stated that

exposure to radiation must be kept as far below the

limits as it is reasonably practicable. Then, it was

modified to “as low as reasonably achievable”

(ALARA) in 1979 (Loewen, 2011). Achievable

means that risks are theoretically feasible to go lower

even if it has been showed not to be practically

possible. Practicable in ALARP, however, focuses on

the fact that technical feasibility needs demonstrating;

it implies that not only is it for technology to be

available, but also the related implementation costs

should be reasonable. Back to the UK, the health and

safety organization (HSE) also specified that risk

should be reduced “As Far As Is Reasonably

Practicable” (SFAIRP). HSE (2014) stated that

ALARP is not necessarily the same as SFAIRP; they

added that the latter is ubiquitously utilized in health

and safety legislation in the UK, while the former is

not. Whereas ALARP originates to the incident back

in 1949, SFAIRP was officially announced in 1974 in

regulation of safety (Sirrs, 2016). Moreover, Ale et al.

(2015) pointed out that ALARP is to be applied to the

level of risk while SFAIRP is to be applied for being

safe. They believe that safety is deemed to be

subjective and affected by values as albeit risk is

quasi-objective and not affected by values. Therefore,

safe SFAIRP leans towards reducing hazards. The

court, later on, mentioned that the point is generally

not made in SFAIRP and so ALARP turned into one

of the main concepts to be used in risk reduction in

industries.

As a consequence, when an engineering design

must be within the thresholds of acceptable residual

risk for fire safety objectives, it initially needs to be

acceptable, if not at least ALARP. The latter means

that risks should not be unacceptable. In the case of

ALARP, CBA must demonstrate the minimization of

the risk.

4 WHY ALARP?

Melchers (2001) held on the point that four matters

should be reviewed, which are fundamental to make

us able to interpret and manage risk in general in

societies:

a) risk definition

b) risk tolerance

c) decision-making framework, and

d) practical risk implementation

Risk in Merrian-Webster dictionary is meant as

“possibility of loss or injury: peril”. However, a

unified meaning of that does not seem to exist in risk

engineering all over the world owing to

COMPLEXIS 2023 - 8th International Conference on Complexity, Future Information Systems and Risk

64

disagreements. It has been meant defined differently

in sociology and psychology based on experts’

viewpoint and the eventual outcome of the risk. In

engineering, notwithstanding, it is just considered

having the same meaning as “probability of

occurrence or chance with following consequences”.

So, as Melchers states, we assume risk as

probabilities of occurrences and its consequences.

As it has been mentioned by several studies so far,

risk has to include necessarily subjective matters and

therefore, risk assessment models are all combined

forms of subjectivity and objectivity. It is objective

since numbers can be assumed as unbiased. Also, as

science improves, models are consecutively modified

and this implies that a model is never perfect. The

subjectivity of risk evaluation is emphasized when we

deem the essential factors in risk management.

Consequently, risk assessment (Melchers, 2001)

should entail:

a) the likely consequences of an accident;

b) the uncertainty in estimation of the

consequences;

c) the perceived probabilities of clarifying the

consequences and/or reducing the

probability of occurrence of those

consequences;

d) the amount of familiarity with the risk;

e) level of knowledge and perception of the

risk and following consequences; and

f) the interplay between political, societal and

personal influences in forming perceptions.

Governments still play an important role, bearing

the responsibility of informing societies about likely

future exposed hazards. Nonetheless, there should be

a correlation between individual and societal

perceptions of risk, and there are not thorough levels

of education in countries in the matter of risk and

control by authorities. The needed expertise for risk

management relies mostly on past experience and it

precludes organizations to assess tunnels objectively,

since history literally brings subjectivity. When we

talk about risk management in technologies, such as

nuclear power or fire safety industries, the mix-up of

biased management is more acute. This is due to the

fact that there is not a sufficient base for this

assessment, except a little past experience and

knowledge. As history states clearly, an industry can

be successful in the far future if there has not been a

huge catastrophe in that industry in the past. Taking

nuclear power as an example, this industry dooms to

failure after Chernobyl and Three-Mile Island

disasters. The positive point of fire safety in roads and

tunnels is that the previously-happened incidents

have not had a huge catastrophic effect on the public

all around the world, like what occurred in nuclear

power, even though the incidents in France-Italy

(Monte Bianco), Switzerland (San Gotthard) and

Austria (Tauern) will not be forgotten in the field of

engineering. So how can a society deal with risk

evaluation enforced by new technology? Philosopher

Habermas (1987) argues that science rationality itself

originates from agreed formalism, not from objective

truth. It means that the evaluation includes knowledge

of humankind and agreement among them for

rationality. In order to have sincere viewpoints

alongside power equality, the rationality of

assessment criteria for risk analysis should originate

from agreement in the society attained through

“internal and open transaction between

knowledgeable and free human beings (Melchers,

2001). Nevertheless, there is a diversity of viewpoints

among experts due to the huge number of subgroups

in a society, which can be seen in the unbiased

parliaments during the past decades. Therefore, the

concept of ALARP could foster assess risk reduction

and control techniques based on already established

technologies.

5 FROM ALARP TO CBA

The word “reasonable” in the concept of ALARP has

brought up some discussions among engineers and

experts so as to find out whether there is an

appropriately effective meaning for it. Several

researchers (e.g., Ale et al., 2015; Van Coile et al.,

2019) believe that reasonable means that costs in

implementation of risk reduction strategies are or

should be substantially disproportionate with the

corresponding benefits. While there is not a

widespread agreement if substantial has the same

meaning as gross, reasonability is believed to be

affected by conceptually surrounding circumstances

up to a point. It is often accepted that reasonability is

affected by circumstances until the decision about the

risk control has been made, while then it will not

change even if circumstances change. However,

practical concept of ALARP has been identified after

the incident and after the related ruling (Ale et al.,

2015). Previously mentioned in this paper, ALARP is

widely reported to be a subjective matter, and this sort

of concept is literally qualitative. One of the positive

points about ALARP as a qualitative blurred concept,

in the process of decision-making, is avoidance of

questions that are difficult to answer as well as

questions correlated with ethical connotations;

nonetheless, whether costs are grossly

disproportionate to risk reduction is the one under

ALARP in Engineering: Risk Based Design and CBA

65

criticism, which is somewhat difficult to respond

(Jones and Aven, 2011). Moving a few steps back

from this discussion, we will have a broader overview

and also realize that too many studies and

implementations are strongly based on the phrase

“grossly disproportionate” announced in 1949, and

this seems to be just playing along with some

coinages and vocabularies. Therefore, “threshold”

seems to supersede a place before “disproportionate”.

Accepting the “grossly or substantially

disproportionate” relationship between the risks and

the costs, denotes that safety measures are applied up

to a point where this relationship holds. Van Coile et

al. (2019) hold on the opinion that the philosophy of

ALARP can be stated by “Equation (2)”, where ∆𝐶 is

the cost of investigated safety feature, ∆𝑅𝐼 is the

associated change, which is negative and we

neutralize it by another negative sign as you can see

in the equation, and ‘a’ is the aforementioned

disproportionality threshold. Van Coile and the

colleagues believe that “the safety feature should be

implemented when the cost benefit ratio

∆

∆

is

below the threshold”. This threshold is the same as

the red lines in Figures 1 and 2. The efficiency, not

the risk level, is assessed via this equation.

∆𝐶

−∆𝑅𝐼

≤ 𝑎

(2)

It can be concluded that the fundamental point of

ALARP can only be approved through appropriate

efficient safety measures (Van Coile et al., 2019), and

these measures can be achieved by CBA. HSE (2001)

has noted that “CBA offers a framework for

balancing the benefits of reducing risk against the

costs incurred in a particular option for managing

risk”. In other words, if validated safety standards and

their practicality are to be under scrutiny and

evaluation, there will not be any other factual

substitute for CBA to do so. Costs are by nature

disproportionate to benefits, every time the former is

higher that the latter, but it does not mean that costs

and benefits must not be clearly defined and

estimated. Benefits of a safety boost are totally

troublesome both qualitatively and quantitatively and

it needs CBA; however, estimation of costs in

implementation of the safety boosts are quite simple

to define, at least in theory. Even though subjectivity

is to be controlled if not rejected altogether, the

aforementioned benefits of the safety measures

should be identified and clarified to let reflect the

preferences of those who are influenced by the

measure implementations. Thus, individuals’

willingness to pay (WTP) is brought up, so as to

recognize the amount of money the influenced

individuals are willing to pay for the decrease in risks

of death and injury with respect to safety measures.

This recognition must be done among a large group

of affected individuals in the society in case of

individual risks and societal risk, so that the value of

precluding a “statistical fatality” or value of

“statistical life” can be transcribed. Therefore, values

of time, environment, involved individuals and future

money to be invested should be assessed. But the

criticism here is about whether it is appropriate to

evaluate all people by WTP. Van Coile and Pandy

(2017) coined the phrase “maximum societal benefit

criterion” to point out that CBA is better assessed in

the concept of ALARP from a societal point of view.

They also added that “societal minimum safety level”

shall be considered by private decision makers. All in

all, ALARP should be evaluated according to a scalar

risk indicator (Expected Value), and should be

specified by societal, risk-neutral and CBA analysis.

In the process of risk evaluation, decision-makers

had better make a risk-neutral assessment. It opens up

the critical discussion of valuing people by money.

Since this topic is completely conflicting, one unique

statement cannot be found in the field in this regard at

all. First and foremost, one group of experts believe

that it is not accepted at all to value people by money

since life of a human-being is priceless. They,

therefore, reject all the procedures following in order

to implement safety measure and perform CBA. The

second group states that there is no way to proceed

through the CBA and handle societal and individual

risks, but valuing people. The statement of this group

evidently causes creation of two opposite extremes.

The first extreme holds on the opinion that all

humankind is the same and if they are supposed to be

valued by money, this amount must be the same. The

second extreme prevails the context stating that

human-beings are valued based on some features,

such as the level of their education. In other words, it

is said that we cannot prescribe one unique CBA for

an upcoming would-be incident since involved

casualties and the dead are differently valued. These

arguments, which are inevitable, make the process of

CBA in the concept of ALARP totally demanding in

terms of later-on influence.

Z(p

)

=

B

–C(p

)

– D(p

)

(3)

Conceptually, CBA is presented by “Equation

(3)”, where Z(p) is total net utility, B is benefits of

implementation of safety measures, C(p) is the cost of

implementation, and D(p) is the total cost of possible

failure or damage. While C and D are functions of an

optimization parameter (p), B is not (Van Coile et al.,

COMPLEXIS 2023 - 8th International Conference on Complexity, Future Information Systems and Risk

66

2019). Nevertheless, the question is whether CBA has

been used as one prominent method to evaluate safety

and assess risk.

6 IS CBA AN APPROPRIATE

MODEL?

Even though explicit assignment of monetary

valuation of human-beings for safety is not accepted

actively or passively in different industries and

sections of the public, it is believed to be inevitable to

make implicit monetary valuation; nevertheless, it

highlights some problems. In the case of wealthy

people in a society, they are surely more able to pay

for their safety; thereafter, there should be equality

among individuals belonging to one group in terms of

value or there must be a representative group

consisting of all socio-economic levels of a society.

In order to do so, distribution weights are adjusted to

values which are inversely correlated with the level

of income in the representative group (Jones and

Aven, 2011). However, these weights are strongly

subjective to assign, making the grossly-

disproportionate relation of cost and benefit

questionable. By principle, a safety measure in CBA

should be implemented only if the costs are less than

the benefits, but benefits are highly probable to be

attained through WTP. Therefore, and owing to the

subjectivity of WTP, costs must be lower than

benefits in order not to accept the other side of the

coin at all. It is the concept of “disproportion” rather

than “grossly disproportion”. HSE, however, insists

on the “grossly” part of the chunk (2001):

“…we believe that the greater the risk, the more

that should be spent in reducing it, and the greater the

bias on the side of the safety. This can be represented

by a ‘proportion factor’, indicating the maximum

level of sacrifice that can be borne without it being

judged ‘grossly disproportionate’. Although there is

no authoritative case law which considers the

question, we believe it is right that the greater the risk

the higher the proportion may be before being

considered ‘gross’. But the disproportion must

always be gross”.

Stating this decree, HSE seems to have been

totally aware of the subjectivity of the case, and it

makes one ponder that a task should have just been

terminated. Not all individuals, not even those who

are willing to pay for their safety, are going to benefit

from the safety boost. Also, CBA cannot always

thoroughly take all uncertainties of the

implementations into consideration. Another point to

be inveighed is that those who are on the brink of

more and higher risk should be asked to pay less while

they should be benefitted from higher levels of safety

improvements and risk lessening. Jones-Lee and

Aven (2011) stated that “…the gross disproportion

interpretation of ALARP reduces the probability that

some of those responsible might seek to avoid

implementation of a safety improvement by

overstating its costs”. It literally highlights the partial

outlook of decision-makers being in touch with

people’s life. They (2011) added that “…the gross

disproportion interpretation of ALARP also provides

an incentive for those responsible to seek to employ

the most efficient and the least costly means of

affecting the improvement or, indeed, to undertake a

fundamental redesign of key safety features”. It is

strongly rejected since the most efficient means are

not always the least costly one, not even always the

costliest one. In other words, it is not true to have one

prescription for all situations and incidents. In

conclusion, and in consistence with Jones and Aven

(2011), grossly disproportionate has not normally

been criticized since it is accepted to be qualitative to

some extent; yet from a quantitative point of view, it

is not evident what it precisely covers.

The other point to ponder is the case of decision-

makers. It has been a debate for decades who they

should be. At first glance, it seems evident that it is

supposed to be a parliament debate. The problem is

that their final decisions cannot be deemed totally

validated since the number of people who are making

the decision must be much higher than the average

number of candidates in a parliament, and this is the

nature of subjective issues. Therefore, some

recommended that the decision-making process

should be left to the public. Nonetheless, the public

are usually ill-literate, uneducated, biased and

irrational, and unenthusiastic about these types of

issues. So as to ignite the public’s enthusiasm, and

making them scientifically and politically aware, it

takes a considerable amount of time. The final

proposal could be collaboration of the authorities and

the public to lessen the touch of subjectivity, dealing

with the time simultaneously. However, the

authorities have never been easy with revelation of

regulatory issues to the public.

Decision-making process is to take salient steps

towards safety improvement in ALARP. This process

needs spending and saving a huge amount of money;

the money that should be less than the benefits of

outcomes. In order to correctly apply these safety

improvements and weigh the balance of uncertainties,

too many researchers suggested CBA. The problem is

that this analysis is more complex to implement when

ALARP in Engineering: Risk Based Design and CBA

67

it deals with more “hazardous facilities where the

value of human life, the cost of suffering and

deterioration of the quality of life may play a major

role in the analysis” (Melchers, 2001). In this case,

CBA assumes one equal weight for all monetary

values, when dealt with social implications. The

instance of tolerable risk is of this type. Thus, the

correlation of vocabularies ‘low’, ‘reasonable’, and

‘practicable’ with minimum total cost in CBA is

blurred. The matter of risk and environmental issues

seem to be out of the perception of CBA, since they

consider them “political risk”.

7 CONCLUSIONS

During decades, ALARP has turned into a main

principle for risk management in several countries.

The European Union, as well as Italy, has learned a

lot of lessons from some disastrous accidents like the

Monte Bianco, the Gotthard, the Tauern tunnel and

Chernobyl, in nuclear power industry. It is true that

the number of incidents per 10 years has considerably

dropped, and this is due to management of societal

and individual risks in a diverse range of locations

where risk is highly eminent. However, some salient

weaknesses can also be seen. From an engineering

point of view, ALARP has developed and all the

directives in EU and Italy lead the path of safety.

Nevertheless, by reading papers and directives

throughout the past decades, it can be seen from a

linguistic point of view that most safety authorities

have been playing the safety along. In other words,

the concentration has been on writing papers and

directives rather than improving safety. This criticism

is literally evident in using various acronyms for

safety, such as ALARP, ALARA, ALAP. The

solution is for EU officials to pass some unified laws

for the whole EU countries after approving the

practicality of the safety measures.

REFERENCES

Abrahamsen, E. B., Abrahamsen, H. B., Milazzo, M. F., &

Selvik, J. T. (2018). Using the ALARP principle for

safety management in the energy production sector of

chemical industry. Reliability Engineering & System

Safety, 169, 160-165.

Alakbarli, E., Gentile, N, S., Guarascio, M. (2023).

Juridical side of ALARP: The Monte Bianco tunnel.

Ale, B. J. M., Hartford, D. N. D., & Slater, D. (2015).

ALARP and CBA all in the same game. Safety science,

76, 90-100.

Directive 2004/54/EC of the European Parliament and of

the Council of 29 April 2004 on minimum safety

requirements for tunnels in the Trans-European Road

Network.

Decreto Legislativo n° 264 del 5 Ottobre 2006 Attuazione

della Direttiva 2004/54/CE relativa ai requisiti di

sicurezza per le gallerie della rete stradale transeuropea.

Edwards v National Coal Board [1949] 1 All ER 743 CA.

Explosives Regulations Act of 2014 (SI 2014/1638)

Guarascio, M. (2008). Italian Risk Analysis for Road

Tunnels. PIARC Technical Committee C3.3 Road

tunnel operation, 209-223.

Guarascio, M. (2021). “As low as reasonably practicable.

How it does work in the rail and road tunnels in Italian

rules. ‘Risk acceptability/tolerability criteria. The

Gu@larp model”, Safety and Security Engineering IX.

Guarascio, M., Berardi, D., Despabeladera, C., Alakbarli,

E., Di Benedetto, Eleonora., Galuppi, M., & Lombardi,

M. (2022). Road Tunnel Risk-Based Safety Design

Methodology by Gu@larp Quantum Risk Model. Risk

Analysis, Hazard Mitigation and Safety and Security

Engineering XIII, 214, 39.

Habermas, J. (1987). Eine Art Schadensabwicklung: Kleine

politische Schriften VI.

Health and Safety Executive (HSE) (2001)

Jones-Lee, M., & Aven, T. (2011). ALARP—What does it

really mean? Reliability Engineering & System Safety,

96(8), 877-882.

Loewen, E. P. (2011, September). Research Reactors-Their

role in ALARA reform and the post-Fukushima

Nuclear Industry. In Address, Annual meeting of the

Test, Research, and Training Reactors organization

(Vol. 15).

Melchers, R. E. (2001). On the ALARP approach to risk

management. Reliability Engineering & System Safety,

71(2), 201-208.

Sirrs, C. (2016). Health and Safety in the British Regulatory

State, 1961-2001: the HSC, HSE and the Management

of Occupational Risk (Doctoral dissertation, London

School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine).

Van Coile, R., Jomaas, G., & Bisby, L. (2019). Defining

ALARP for fire safety engineering design via the Life

Quality Index. Fire Safety Journal, 107, 1-14.

COMPLEXIS 2023 - 8th International Conference on Complexity, Future Information Systems and Risk

68