Self-Dependency Amelioration and Dignity Revival for South-East

Asian Older Adults: Using Technology as a Means and Method

Sanchita S. Kamath

a

and Sophia Rahaman

b

School of Engineering and IT, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Dubai Campus, U.A.E.

Keywords: Ageing Well, Human Computer Interaction, Data Visualization, Quantitative Analysis.

Abstract: Self-Dependency in Older Adults is broadly a measure of their morale and self-worth. The purpose of this

research is to understand how far the engagement and interaction between elderly and the younger members

of their family affects their lifestyle and self-esteem and how technology can help revive the dignity of the

elderly by helping them cope with the changes in their life and the fast-pacing world. Positive and Negative

Engagement criteria from previous research has been employed to develop codes based on which questions

have been designed. The lifestyle choices and past behaviour that the elderly and their younger family

members hold is collected and quantified through two separate parallelly and strategically designed surveys

which both factions have answered. It was observed that gender plays a role in the priorities of South-East

Asian Older Adults, and they do not have any major discrepancies between the thinking of the elderly and

their family member. Analysis of such insights helped generate themes which inform the model for

technological intervention which can help revitalize the self-confidence of the elderly.

1 INTRODUCTION

There are several aspects in gerontology that

contribute to the concept of ‘Ageing Well’. Ranging

from globalized general issues such as human rights,

ethics (Pirzada et al., 2022), social security, and

economic impacts of an ageing population to

personalized concerns such as physical activities,

mental disabilities, perceived isolation, and the

impact of smaller social networks (Banerjee et al.,

2021) on the psyche of the elderly, there is a lot of

scope for technological intervention, which this

research aims to assess. The central key to be able to

understand the requirement of the interference, or the

lack thereof, is to collect and assess the sensitivity and

discernments of the elderly regarding their social

environment, which is the objective of this paper.

One can only imagine the importance of the

support received from healthcare professionals,

caretakers, and family in the psychosocial abilities of

the elderly. The aforementioned factions are elements

that help the elderly cope up with prejudice, bias,

vulnerabilities, and helplessness associated with

ageing. The aim of this paper is to extend themes

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6469-0360

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2781-4659

previously researched by the authors (Kamath and

Rahaman, 2022) on the engagement of senior citizens

in a family setting by understanding the perceptions

of the elderly on those needs to quantify their

preferences and requirements, done through

gathering responses from a curated survey based on

the codes derived from previous research.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

The preservation of the dignity of the elderly has been

fundamentalized to initiate through making the needs

of the elderly and work towards a balance between

providing them a safe environment to voice opinions

and a ‘cloak of invisibility’ to shield their dignity,

especially in healthcare settings (Clancy et al., 2021).

This brings forward an opportunity for technology to

play the role of a mediator and connector; to be able

to support and protect the needs of the elderly.

Further, the perceptions of dignity are

individualized among the elderly. Research

conducted (Váverková et al., 2022) has shown that a

differential exists for the same based on gender – men

178

Kamath, S. and Rahaman, S.

Self-Dependency Amelioration and Dignity Revival for South-East Asian Older Adults: Using Technology as a Means and Method.

DOI: 10.5220/0011957900003476

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2023), pages 178-185

ISBN: 978-989-758-645-3; ISSN: 2184-4984

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

have a more negative outlook to ageing and a feeling

of helplessness in their life. Hopelessness in Older

Adults has been measured through the Social

Hopelessness Questionnaire (Flett et al., 1993) which

measured subjective well-being of the participants

through positive and negative psychological factors

(Heisel and Flett, 2022). Robot Companions specially

catering to the needs of the elderly by paying special

attention to their preferences (Coghlan et al., 2021) is

one of many steps taken towards using technology to

be able to help the elderly through Human-Robot

Interaction Studies (Søraa et al., 2022). Research is

being conducting to measure the quality of life

(Kisvetrová et al., 2019) and its impact on mental

deterioration of the elderly and how it can be handled

(Banerjee et al., 2021) (Holthe et al., 2022)

(Strnadová, 2018). Older Adults dynamically

evaluate their care (Kabadayi et al., 2020); their

experience provides context to research in “Ageing

Well” and the use of technology to help practitioners

and family provide customized care.

Social Contexts and Assumptions also affect the

view that elderly have towards themselves – thinking

their lives are ‘less worth’ since they have aged,

which is a major obstacle that must be overcome on

the path to reviving self-worth. Research (Couto and

Rothermund, 2022) has developed four ‘prescriptive

views’ of Ageing which has inspired this research and

is aligned to Positive and Negative Engagement from

previous work. Social support is crucial for the

Attributed Dignity of the elderly (LeBlanc and

Jacelon, 2022) (Akhter-Khan et al., 2022) which is

the focus of this paper – the external locus of their

self-esteem. Majority of research conducted focusses

on psychometry with respect to the elderly (Han et al.,

2022) (Van Bijsterveld et al., 2022) and their

requirements in a healthcare setting, albeit extremely

varied (Johnson et al., 2022) (Scolaro and Formosa,

2022) (Bluck et al., 2022). This paper aims to extend

current research and insights in psychology and

technology specialized for encouraging self-reliance

in the elderly. The three tenets of the Self-

Determination Theory (Deci and Ryan, 2000) have

been looked at through the model – focus is shed on

autonomy motivated by (Mikus et al., 2022). By

including the social vicinity of Older Adults through

the attempt of using technology as a tool to help fulfil

their social needs, self-independence is revived.

3 METHODOLOGY

To understand the concept of Ageing Well, it is

paramount to understand the expectations of the

elderly, and their relationship with their family

(especially younger members and children), as

aforementioned, being a huge part of their life

becomes a fundamental aspect that needs to be

investigated.

3.1 Research Questions

The research questions that were postulated are:

Does gender have a significant role in the

outlook development of the elderly?

What can be understood as Positive and

Negative Engagement for the elderly?

Is there discrepancy between the responses of

the elderly and the younger members in their

family, indicative of a lack of communication

and understanding?

Do Older Adults want to learn technology from

their younger family members?

Hence based on previous theorization and

research conducted (Kamath and Rahaman, 2022),

codes were generated to help answer the research

questions and develop themes for possible

technological intervention and the lack thereof.

Figure 1: Methodology of the research conducted.

Based on the codes, questions were developed to

further understand user views. There were two

parallel questionnaires created, that allowed the input

of dual data for the similar question, one from the

older adults themselves (age threshold was set to 65

years and above), and other from the family of the

elderly. Users were asked to rate their inclination of

the conducting a particular process or action for their

family which help quantize expectations of the

elderly. This data collection methodology is akin to

(Carvajal et al., 2021).

These questions were roped into a survey, and the

response was to be a number on the scale of one to

five for every question. The user could rate the

possibility of them having conducted a particular

action or behaviour in the past or the likelihood of

Self-Dependency Amelioration and Dignity Revival for South-East Asian Older Adults: Using Technology as a Means and Method

179

them performing the said action in the future which

helped understand their stance. These questions

majorly focussed on the engagement of Senior

Citizens with the younger members of their family.

3.2 Survey Development

The survey developed consisted of eleven questions

that were developed based on the codes and other

questions asking for the certain non-intrusive

personal details such as name and age (the

questionnaire for the Younger Family Members

(YFM) asked for their relation to the elderly).

Table 1: Codes and Corresponding Questions.

ID Code En

g

a

g

ement Q No.

C1 Guidance Positive 1, 3

C2 Support Positive 2

C3 Independence Negative 4

C4 Clash of Opinions Negative 5

C5 Priorities Ne

g

ative 6, 7

C6 Attitude Ne

g

ative 8

C7 Lifest

y

le Choices - 9, 10

C8 Tech Acceptance - 11

This is an overview of the codes chosen based on

Positive and Negative Engagement, specifically

tailored for Older Adults. The questionnaire was

designed in such a way that the questions were

semantically simple to understand, short, and the

required no more than two minutes to complete.

3.3 Participant Information

The purpose of conducting this survey was to

understand how far younger members of the family

are willing to help their elderly or wish to rely on

them and to what extent Older Adults appreciate the

same and wish to be a part of their family’s life and

derive self-gratification from it. Following is the

summarization of data of the 41 Older Adults who

took the survey. The gender ratio of the data pool is

close to 1:1, with 20 Females and 21 Males.

Table 2: Older Adult Participants’ Data Overview.

Age No. of Older Adults Gende

r

60-65 7 4 Female, 3 Male

66-70 16 7 Female, 9 Male

71-75 8 3 Female, 5 Male

75 + 10 6 Female, 4 Male

Pairs of elderly and family members who have

answered the questionnaire, are lesser than the total

number of Older Adults who did.

Table 3: Young Family Participants’ Data Overview.

A

g

e No. of Older Adults Gende

r

20-40 10 1 Female, 9 Male

41-50 11 5 Female, 6 Male

51-60 3 2 Female, 1 Male

60-65 1 1 Male

Thus, while the analysis of all Older Adult

responses contributes towards better understanding of

the concept of “Ageing Well”, the pair data is

specifically informing the aspect and importance of

the engagement of Senior Citizens with younger

members of their family. Mapping of the family

member and Older Adult is done below.

Table 4: Pair Participants’ Data Overview.

ID Older

Adult

Elder’s

Gende

r

YFM’s

Gende

r

Elder’s

A

g

e

YFM’s

A

g

e

F01 O01 Female Female 77 53

F02 O02 Male Male 68 42

F03 O05 Female Female 73 46

F04 O03,

O04

Female,

Male

Male 68, 76 39

F05 O07 Female Female 84 55

F06 O13 Female Male 70 21

F07 O23 Male Male 69 45

F08 O22 Female Male 63 40

F09 O21 Male Male 68 25

F10 O20 Male Male 65 30

F11 O12 Male Male 75 42

F12 O28 Female Female 72 49

F13 O27 Female Male 64 38

F14 O26 Female Female 68 48

F15 O25 Male Female 74 45

F16 O24 Male Male 69 43

F17 O35 Male Female 72 42

F18 O36 Male Male 62 32

F19 O33 Male Male 63 23

F20 O32 Female Male 65 45

F21 O18 Male Male 80 52

F22 O39 Female Male 68 33

F23 O37 Female Female 77 51

F24 O38 Male Male 75 48

F25 O40 Female Female 67 37

F26 O41 Male Male 84 62

4 DATA ANALYSIS

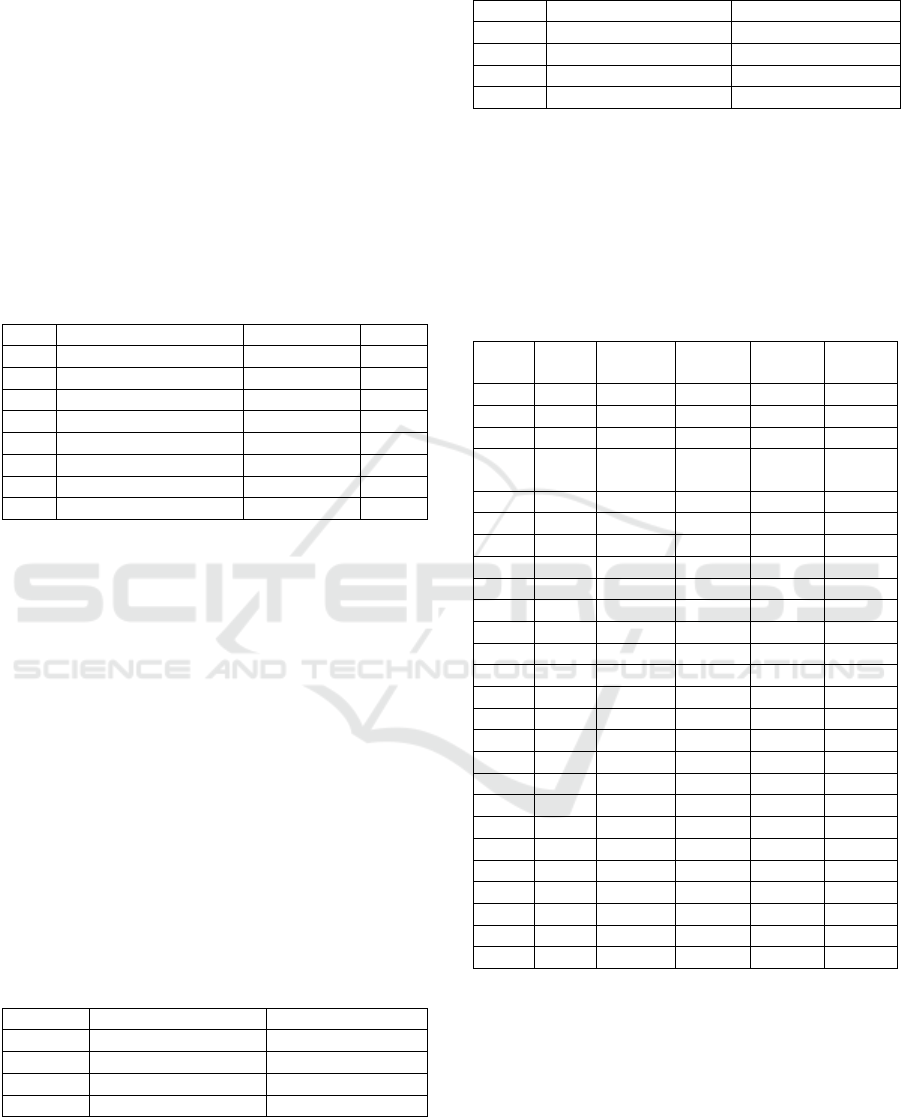

To visualize the data collected, the metrics of gender

was taken as the qualitative factor for Data

Categorization, mapping it to the age of elderly as

below. This helped understand that the pool was

majorly homogenous; conclusion derived from the

age visualization and the similarity of the responses.

ICT4AWE 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

180

Figure 2: Visualization of the Data Pool.

The Aged Population was asked to self-report on

questions such as “I feel purposeful when my family

asks me for advice” (Q1), “I will support the younger

members of my family financially if they need it”

(Q2), “I will not tell my family about my opinions,

because they will not agree with me or disrespect my

opinion” (Q5), “I lash out at my family when they try

to help me with chores” (Q8) and “I want to learn how

to use new gadgets from my family” (Q11) through a

scale of 1-5. Corresponding questions for the YFM

were “I look to the elderly in my family for any advice

I need” (Q1), “I don’t mind asking my elderly to help

me financially” (Q2), “I will not tell my elderly

family members about my opinions, because they will

not agree with me or disregard my opinion” (Q5), “I

would keep helping my elderly family members,

despite being shouted at” (Q8) and “I feel overjoyed

when my parents attempt to learn new age technology

from me” (Q11) which is how results were derived,

by comparing the degree of miscommunication. Each

of these questions, are coded to Positive and Negative

Engagement, based on previous research (Kamath

and Rahaman, 2022). The visualization of the self-

report scores for each question (with corresponding

code) are done below.

4.1 Visualizations

Figure 3: Mapping the Responses with Codes.

It was observed that while there was a majority

agreement to Positive Engagement with Family, there

was more of a neutral stance to most questions on

Negative Engagement. Most participating Older

Adults wished to learn operating technology from

their family member. The theory of the elderly having

a strong external locus of esteem is not adequately

supported by Question with Code Lifestyle and

Independence, since responses were neutral.

Figure 4: Determining Discrepancies in outlook based on

Gender (Ratio being 1:1) for Older Adults.

Figure 5: Determining Discrepancies in outlook based on

Gender for Younger Family Members.

Comparing the gender wise response of Older

Adults for every question, one can see that there is a

significant change in question coded Priorities 1 and

Lifestyle Choices 1. This can be attributed to the

specific South-East Asian upbringing, which has long

supported patriarchy and expects men and women to

prioritize different tasks in life and expects them to

live their lives differently. Yet, as times are changing

this gap may be filled, as seen in Figure 5 (though, the

pool of data for the YFM has more males than females

– 17 men and 9 women, construing the visualization).

Although, one can observe that while data is majorly

Self-Dependency Amelioration and Dignity Revival for South-East Asian Older Adults: Using Technology as a Means and Method

181

congruous between gender responses of the elderly

and YFM, YFM male participants are more likely to

give a radical response of 4 for most questions, which

was not seen with the Older Adults.

5 RESULTS

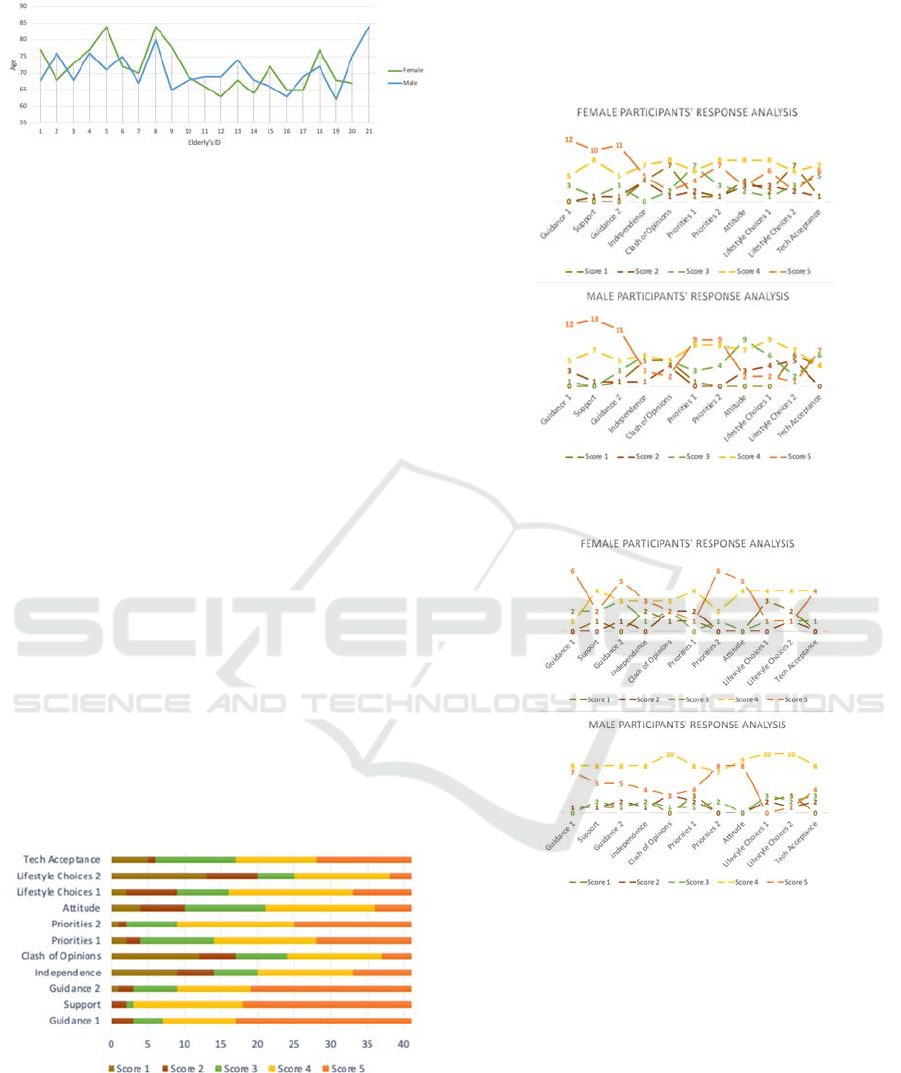

In the pair data, no significant discrepancies were

found between the perceptions of the elderly and the

younger family member when answering any

question, which shows that within the pool of data

that was collected, the understanding shared was

strong. In a culturally and socially diverse group, the

same might not be observed. Hence, one may

conclude that while for the South-East Asian culture

RQ3 is a no, the same might not be true for other

cultures. There is no significant observable difference

between the outlook of male and female participants

in the study as seen below. This shows that gender

might not be a significant determining factor for the

technological intervention answering RQ1. Positive

Engagement had a higher variance between

favourable and non-favourable responses as

compared to Negative Engagement. This indicates

that while most Older Adults agree to what actions

they purport towards their family, they do not agree

to the reactions they would give under certain

difficult circumstances, giving an answer to RQ2.

Figure 6: Visualization for Engagement Categories.

Yet, analysis of gender as a primary factor for

categorization as seen in Figure 4, one can observe

that males are more likely to want co-habitation than

females who tend to prioritize the needs of their

family more than their own. This seeds from a

patriarchal society rampant in South-East Asia and a

consequent generational upbringing difference as

aforementioned. RQ4 is answered through the survey,

wherein Older Adults do want to learn technology

from their Younger Family Members and the YFM

also wish to engage and teach the former.

5.1 Themes Generated

Figure 7: Themes for Technological Intervention.

The themes generated are based on the Self-

Determination Theory and cover the three major

tenets – Autonomy (Behaviour), Competence

(Skills), and Relatedness (Attachment).

5.2 Technological Intervention Model

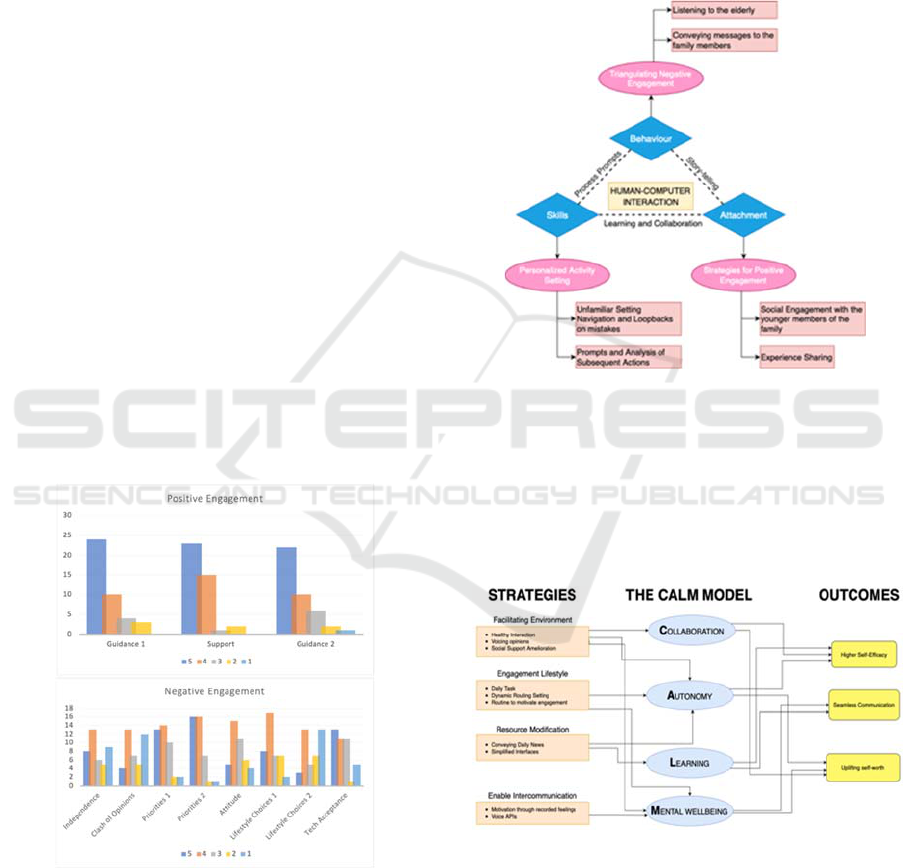

Figure 8: Technological Intervention Model – CALM.

Strategies developed in the model include Facilitating

the Environment (Involving healthy interaction

between machine and the elderly and the elderly and

their family members, Giving the elderly a platform

to voice their opinions, and Social Support provided

through interaction with elderly of similar age

groups), Engagement Lifestyle (providing the elderly

ICT4AWE 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

182

with a daily list of tasks to complete, setting a

dynamic routine for them based on changing needs

and a daily time to interact with friends and family),

Resource Modification (changing the means to

convey information to the elderly making it easier for

comprehension and interaction through interface

modification and content modulation) and Enabling

Intercommunication (allowing the elderly to speak

with the system and then interact back with them

through a Voice API to enable a feeling of

companionship). These Strategies Fuel the CALM

model as seen in Figure 7 and results in Revival of the

Dignity of the elderly.

The technological intervention model, relays the

above defined themes to systemize interfaces and

create software that cater to the needs of the elderly,

promoting Positive Engagement and reducing

Negative Interactions by creating a clear

communication channel. Further for privacy:

There should be a threshold to the information

that is being collected from the Senior Citizens.

Any information that is being relayed must go

through a channel that is authorized.

The model developed for Behavioural Analysis

must keep in mind the past experiences of the

elderly, producing Context-informed and

Trauma-Informed tasks.

6 DISCUSSION

In this research, technology refers to interfaces and

devices that being generally used currently. This is

the technology that is readily available in the market,

and cater to a broad range of users, not just the Older

Adults. Hence, this study has been conducted to

understand the role of this technology and how it must

be modified to suit the Older Adults better, and more

importantly, the role of intergenerational

conversation in training Older Adults and

acclimatizing them to technology and a subsequent

boost in their morale and dignity.

When the survey was circulated, the users were

informed to answer the questions based on their

understanding. The final question, which asked the

users whether they wanted to learn/teach technology,

they understood that being common devices they use

daily to complete their tasks such as mobile phones

for calling (specifically smart phones which Older

Adults found complicated in general) and other

screens (like tablets, laptops) which they use

occasionally. This is similar to the idea the

researchers had while conceiving the survey.

Users were selected based on their age. The Older

Adults would have to be 65 and older, and their

children (caregivers and other family members such

as nieces and nephews have not been included in the

study) were taken to form a pair. Then the data from

this pair was matched to see if their attitude and

responses towards corresponding questions was

same.

While this research is set without assumptions, it

does apply only quantified data. In-person qualitative

interviews could not be conducted which would have

given a deeper in-depth understanding into the lives

of the elderly and their expectations from their life

and their reliance on themselves and their family.

Quantitative Data usage along with Surveys as a

method of Data Collection was chosen not only to

broaden the pool of people who are involved, but also

to check if the elderly were willing to use technology

to answer the survey. Further, their behavioural

tendencies were self-measured which reduces bias.

Yet, it is understandable that the usage of qualitative

data is essential to Computer Supported Cooperative

work (CSCW) and has been flagged as the future

scope of this research. Furthermore, the number of

responses that could be collected isn’t majorly

extensive, and analysis could be made further

accurate with a larger response pool. There is no

significant research done on which of the

codes/aspects is most important, and the number of

questions if more for a particular code, are not due to

the rank of the importance of the code, but because

there were multiple aspects within the code which

could be covered and quantized through the survey.

Primary research in integrating technology with

Ageing includes five “domains of well-being” –

Health, Safety, Activities of Daily Living, Social and

Financial (Lorenzen-Huber et al., 2011), which

inspired the themes developed. The themes generated

keep well-being at the centre of the intervention and

privacy is a major aspect that must be balanced.

Ethnicity of the individuals was not taken as a

measure or altering factor because the survey

conducted on a homogenous sample of older adults of

differing ages. Due to cultural differences, there can

be a marked change expected in the responses which

is a theme further research shall explore. It is

recognized that the responses received are not

completely representative of every ethnicity within

the country itself, and its role in familial bondage can

be an interesting line of research. Further, the current

model postulated doesn’t keep in mind, the possible

discrepancies that might arise due to

miscommunication and possible handles for the same.

Self-Dependency Amelioration and Dignity Revival for South-East Asian Older Adults: Using Technology as a Means and Method

183

Describing the Technological Intervention

Model:

Facilitating Environment refers to having

continuous interaction among the generations

of family members, and healthy

communication between family members

wherein they are completely honest with each

other about their thoughts and feelings with or

through the encouragement of technology.

Engagement Lifestyle majorly will deal with

the daily tasks that a person is conducting

which can be dynamically set and reset by the

Older Adult which will help motivate them to

complete their routine tasks which they might

feel they cannot complete due to some

psychological or physical disability or because

they simply do not feel up to it.

Resource Modification helps conveying daily

information (news) for the Older Adults to keep

on top of general world issues. These message

conveying platforms can be Simplified

Interfaces, Voice Interfaces, Augmented

Reality and other emerging technologies or a

combination of the aforementioned.

Enabling Intercommunication helps users to

stay motivated to share their feelings and

express themselves through their medium of

choice (conversation or writing) which

technology (mobiles, laptops etc.) can certainly

help with.

The CALM Model involves Collaboration,

Autonomy, Learning and Mental Wellbeing

which inputs the strategies from the Model to

generate outcomes such as Higher Self-

Efficacy (making the Older Adults feel like

they can accomplish anything they want to or

set their mind to), Seamless Communication

(which can help users communicate efficiently

with the world, and their family members) and

Uplifting self-worth to be able to ‘re-believe’ in

themselves and their abilities.

7 FUTURE RESEARCH

Ethnicity and culture of individuals plays a major role

in the shaping up of human personality. Hence, future

research would focus on this aspect. One needs to

warrant if intergenerational interaction is welcome in

all cultures and how integral it is to the maintaining

the dignity in Older Adults. Further studies to

understand which fields technology can be applied to

help revive their dignity is a future scope of this study

while focussing on the modalities being used.

8 CONCLUSIONS

The major metrics for Ageing well, in extension to

previous research is the Quality of Life and

Healthcare Policies that must be systemized. The

model proposed keeps this in mind, and constraints to

the same must be set based on policies that might have

to be legalized for the betterment of the ageing

population. The impact of generational difference

should be mitigated as time progresses and the current

youth ages, due to a more egalitarian society in the

present. This paper has analysed data collected from

a specific demographic and answered the research

questions proposed specific to the demographic. To

support the health and well-being of the elderly, such

a behavioural technological model is a first step of

many towards “Ageing Well”. The authors hope to

further this research by interface development and

usability testing.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to extend a warm thank you

and deepest gratitude to Mr. Pradeep Singh, Mr.

Ayush Kumar, and Mrs. Kavita Kamath for their

indispensable contribution towards Data Collection.

REFERENCES

Akhter-Khan, S. C., Prina, M., Wong, G. H. Y., Mayston,

R., & Li, L. (2022). Understanding and Addressing

Older Adults’ Loneliness: The Social Relationship

Expectations Framework. Perspectives on

Psychological Science, 10.1177/17456916221127218.

Banerjee, D., Rabheru, K., Ivbijaro, G., de Lima, C. A.

(2021). Dignity of Older Persons With Mental Health

Conditions: Why Should Clinicians Care?, Frontiers in

Psychiatry, vol. 12, p. 774533.

Banerjee, D., Rabheru, K., de Lima, C. A., Ivbijaro, G.

(2021). Role of Dignity in Mental Healthcare: Impact

on Ageism and Human Rights of Older Persons. The

American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, vol. 29, no.

10, p. 1000-1008. DOI: 10.1016/j.jagp.2021.05.011.

Bluck, S., Mroz, E. L., Wilkie, D. J., Emanuel, L., Handzo,

G., Fitchett, G., Chochinov, H. M., Bylund, C. L.

(2022). Quality of life for older cancer patients:

Relation of psychospiritual distress to meaning-making

during dignity therapy. American Journal of Hospice

and Palliative Medicine, vol. 39, no. 1, p. 54-61. DOI:

10.1177/10499091211011712.

Carvajal, B. P., Molina-Martínez, M. Á., Fernández-

Fernández, V., Paniagua-Granados, T., Lasa-Aristu, A.,

& Luque-Reca, O. (2022). Psychometric properties of

the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire

ICT4AWE 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

184

(CERQ) in Spanish older adults. Aging & Mental

Health, vol. 26, no. 2, p. 413-422. DOI:

10.1080/13607863.2020.1870207.

Clancy, A., Simonsen, N., Lind, J., Liveng, A., Johannessen

A. (2021). The meaning of dignity for older adults: A

meta-synthesis. Nursing Ethics, vol 28, no. 6, p. 878-

894. DOI: 10.1177/0969733020928134.

Coghlan, S., Waycott, J., Lazar, A., Neves B. B. (2021).

Dignity, Autonomy, and Style of Company:

Dimensions Older Adults Consider for Robot

Companions. In Proceedings of the ACM on Human-

Computer Interaction, vol 5, CSCW1, Article 104, p. 1-

25. DOI: 10.1145/3449178.

De Paula Couto, M. C., Rothermund, K. (2022).

Prescriptive Views of Aging: Disengagement,

Activation, Wisdom, and Dignity as Normative

Expectations for Older People. Subjective Views of

Aging, International Perspectives on Aging, vol. 33, p.

59-75. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-031-11073-3_4.

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M. (2000). Self-Determination Theory

and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social

Development, and Well-Being. American Psychologist,

vol. 55, no. 1, p. 68-78. DOI: 10.1037//0003-

066X.55.1.68.

Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., & Gayle, B. (1993). The Social

Hopelessness Questionnaire: Development, validation,

and association with measures of adjustment. In 101st

annual conference of the American Psychological

Association, Toronto, Canada.

Han, S., Ji, M., Leng, M., Zhou, J., Wang., Z. (2022).

Psychometric properties of self-reported measures of

active ageing: a systematic review protocol using

COSMIN methodology. BMJ Open, vol. 12, no. 3,

DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059360.

Heisel, M. J., & Flett, G. L. (2022). The Social

Hopelessness Questionnaire (SHQ): Psychometric

properties, distress, and suicide ideation in a

heterogeneous sample of older adults. Journal of

affective disorders, vol. 299, p. 475-482. DOI:

10.1016/j.jad.2021.11.021.

Holthe, T., Halvorsrud, L., Lund, A. (2022). Digital

Assistive Technology to Support Everyday Living in

Community-Dwelling Older Adults with Mild

Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. Clinical

Interventions in Aging, vol. 17, p. 519-544. DOI:

10.2147/CIA.S357860.

Johnson, I. G., Morgan, M. Z., Jones, R. J. (2022). Oral

care, loss of personal identity and dignity in residential

care homes. Gerodontology, p. 1-7. DOI:

10.1111/ger.12633.

Kabadayi., S., Hu, K., Lee, Y., Hanks, L., Walsman, M.,

Dobrzykowski, D. (2020). Fostering older adult care

experiences to maximize well-being outcomes: A

conceptual framework. Journal of Service

Management, vol. 31, no. 1, p. 953-977. DOI:

10.1108/JOSM-11-2019-0346.

Kamath, S., Rahaman, S. (2022). Engagement of Senior

Citizens in a Family Setting to Help Revive Dignity: A

Study. In Proceedings of the 8th International

Conference on Information and Communication

Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health -

ICT4AWE, p. 307-314. DOI: 10.5220/001107

4800003188.

Kisvetrová, H., Herzig, R., Bretšnajdrová, M., Tomanová,

J., Langová, K., Školoudík, D. (2019). Predictors of

quality of life and attitude to ageing in older adults with

and without dementia. Ageing and Mental Health, vol.

25, no. 3, p. 535-542. DOI: 10.1080/13607863.

2019.1705758.

LeBlanc, R. G., Jacelon C. S. (2022). Social Influences on

Perceptions of Sense of Control and Attributed Dignity

Among Older People Managing Multiple Chronic

Conditions. Rehabilitation Nursing, vol. 47, no. 3, p.

92-98. DOI: 10.1097/RNJ.0000000000000369.

Lorenzen-Huber, L., Boutain, M., Camp, L. J., Shankar, K.,

Connelly K. H. (2011). Privacy, Technology, and

Aging: A Proposed Framework. Ageing International,

vol. 36, p. 232-252, DOI: 10.1007/s12126-010-9083-y.

Mikus, J., Grant-Smith, D., & Rieger, J. (2022). Cultural

Probes as a Carefully Curated Research Design

Approach to Elicit Older Adult Lived Experience.

In Social Justice Research Methods for Doctoral

Research, p. 182-207.

Pirzada, P., Wilde, A., Doherty, G. H., Harris-Birtill, D.

(2022). Ethics and acceptance of smart homes for older

adults. Informatics for Health and Social Care, vol. 47,

p. 10-37. DOI: 10.1080/17538157.2021.1923500.

Scolaro, A., Formosa, M. (2022). Residents’ Perceptions of

Dignity in Nursing Homes for Older Persons: A

Maltese Case-Study. In Perspectives on Wellbeing:

Applications from the Field (pp. 225-239). DOI:

10.1163/9789004507654_014.

Strnadová, I. (2018). Transitions in the Lives of Older

Adults With Intellectual Disabilities: “Having a Sense

of Dignity and Independence. Journal of Policy and

Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, vol. 16, no. 1, p.

58-66. DOI: 10.1111/jppi.12273.

Søraa, R. A., Tøndel, G., Kharas, M. W., & Serrano, J. A.

(2022). What do Older Adults Want from Social

Robots? A Qualitative Research Approach to Human-

Robot Interaction (HRI) Studies. International Journal

of Social Robotics, p. 1-14. DOI: 10.1007/s12369-022-

00914-w.

Váverková, R., Kisvetrová, H., Bermellová, J. (2022).

Gender Differences in the Perceptions of Dignity

among Hospitalized Older Adults. Ošetřovatelské

perspektivy, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 31-43. DOI:

10.25142/osp.2022.011.

Van Bijsterveld, S. C., Barten, J. A., Molenaar, E. A. L. M.,

Bleijenberg, N., de Wit, N. J., & Veenhof, C. (2022).

Psychometric evaluation of the Decision Support Tool

for Functional Independence in community-dwelling

older people. Journal of Population Ageing, p. 1-23.

DOI: 10.1007/s12062-022-09361-x.

Self-Dependency Amelioration and Dignity Revival for South-East Asian Older Adults: Using Technology as a Means and Method

185